Abstract

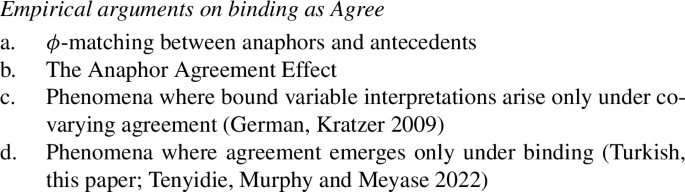

Whether the operation Agree should be taken to underlie anaphoric binding has been the topic of much recent debate. In this paper, we provide a novel empirical argument in favor of the role of ϕ-features and Agree in binding. The argument revolves around the intimate relationship between agreement and anaphora in the Turkish nominal domain, where certain complex pronominals can agree only if they locally bind an anaphor or bound pronoun. We argue that these facts can be readily understood if ϕ-features are crucially implicated in the syntactic derivation of binding. At the same time, we argue that not all binding can be reduced to Agree, based on data from Turkish PPs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

An ongoing debate within generative grammar concerns the status of Condition A of the Binding Theory (Chomsky 1981).

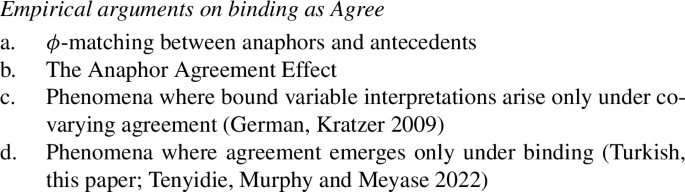

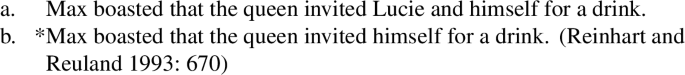

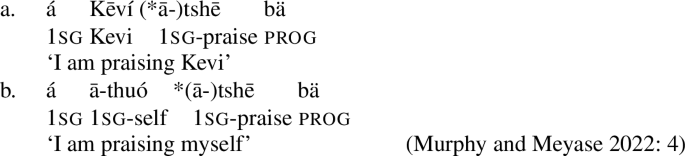

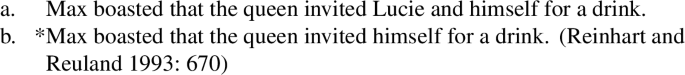

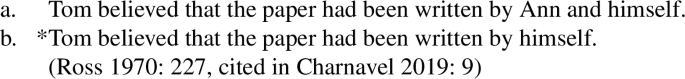

One prominent view holds that the effects of Condition A can be reduced to the operation Agree (Hornstein 2001, 2007; Reuland 2001, 2006, 2011; Kayne 2002; Zwart 2002; Quicoli 2008; Heinat 2009; Hicks 2009; Kratzer 2009; Antonenko 2011, 2018; Bader 2011; Drummond et al. 2011; Rooryck and vanden Wyngaerd 2011; Wurmbrand 2017; Messick and Raghotham 2022; Murphy and Meyase 2022). The proposals in this body of work share the intuition that Agree is involved in the derivation of anaphoric relations, and sometimes diverge in terms of the nature of the features involved: some accounts treat binding as transmission of ϕ-features (e.g. Kayne 2002; Reuland 2006; Kratzer 2009), while others posit Agree for dedicated features related to anaphors (Hicks 2009).

A different line of work opposes the reduction of anaphoric binding to Agree (Safir 2014; Charnavel and Sportiche 2016; Charnavel 2019; Preminger 2019; Rudnev 2020; Bruening 2021). Once again, these proposals do not necessarily form a homogeneous whole, sometimes maintaining different views of what Condition A effects should be attributed to.

Defenses of binding-as-Agree often begin from a largely conceptual standpoint. This conceptual orientation arises largely from two important considerations. Firstly, Minimalist thinking admits no syntactic operation beyond Merge and Agree (Chomsky 2000, 2001). In work where strict adherence to Minimalist tenets is judged necessary, reducing Condition A to one of the two fundamental syntactic operations thus becomes a theory-internal imperative, at least for some authors (see e.g. Hicks 2009: 6–8; Rooryck and vanden Wyngaerd 2011: 1). Secondly, as has been repeatedly pointed out (most recently in Preminger 2019), the mechanics of (standard) Agree do not straightforwardly align with the particulars of anaphoric binding. For example, one popular formulation of Agree involves transmission of features upwards from a valued XP goal to an unvalued head probe (Chomsky 2000). Against this background, anaphoric binding seems recalcitrant in a few ways. In binding, ϕ-features seem to be passed downwards, from the antecedent to the anaphor; moreover, binding ostensibly involves a dependency between two DPs, as opposed to a head and a DP.

Agree-based accounts of binding thus face a serious technical challenge. Much work acknowledges a theoretical pressure to reduce binding to the primitive operation Agree; but the apparent mismatch between Agree configurations and binding configurations makes this reduction less than straightforward. It is thus not uncommon for theories of Agree-mediated binding to assert that, for theory-internal reasons, Agree must be involved, before proceeding to detail how anaphoric binding can be made to fit the profile of agreement dependencies. A wide variety of different implementations has been proposed, perhaps reflecting the difficulty of fully identifying binding with Agree.

Importantly, the prevalence of these conceptual concerns has led to interesting empirical questions being left relatively unaddressed. One of these questions, stated immediately below, forms the point of departure for this paper.

-

(1)

Does binding ever show the morphological reflexes of ϕ-agreement?

With respect to (1), two empirical observations are often adduced in support of binding through Agree for ϕ-features (e.g. Kratzer 2009: 195–197). Firstly, anaphors tend to match the ϕ-features of their antecedents; secondly, anaphors often fail to control co-varying agreement (the Anaphor Agreement Effect; Rizzi 1990); see Sect. 4.1 for more discussion.

But Agree-based accounts may make even more specific predictions regarding the interplay between anaphora and agreement. In particular, if binding establishes Agree dependencies beyond those needed for the purposes of agreement, we might wonder if binding ever repairs agreement configurations that would otherwise fail. This way of thinking leads to a more specific instantiation of (1), namely (2):

-

(2)

Does binding ever license agreement possibilities that would otherwise be illicit?

Against the background of (2), this paper has two goals.

The paper’s first goal, and its main focus, is to present a case study on (2). We will argue that an intricate agreement pattern in the Turkish nominal domain instantiates one case where the answer to (2) is affirmative, thus providing striking support for Agree-based accounts of binding that involve transmission of ϕ-features.

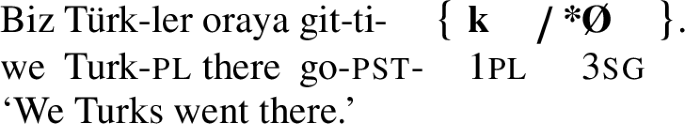

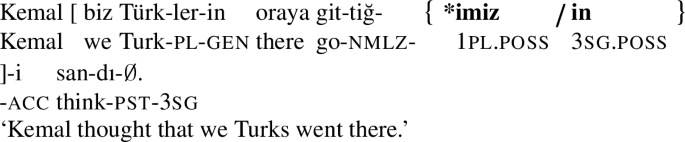

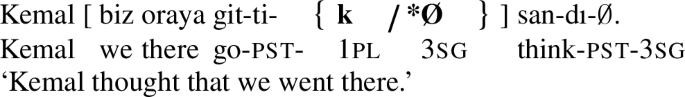

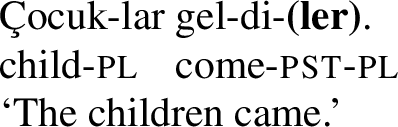

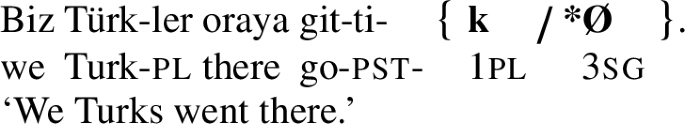

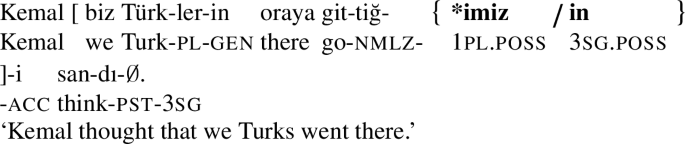

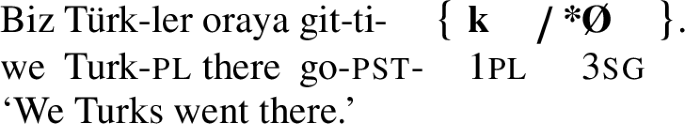

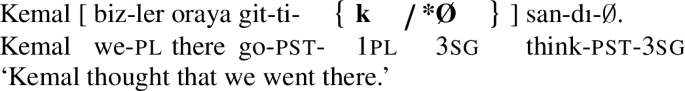

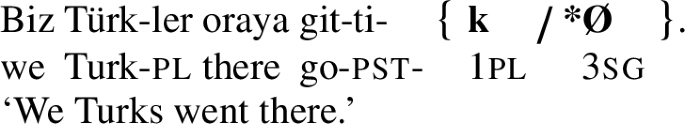

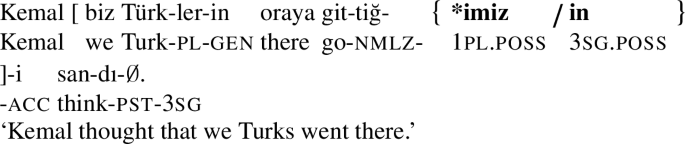

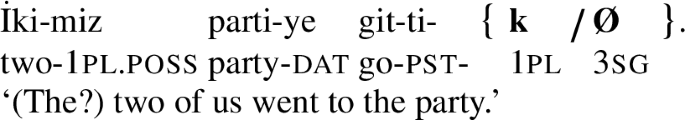

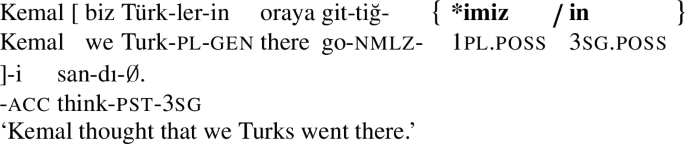

The basic pattern is as follows. In one variety of Turkish (see Sect. 2.2.1 and footnote 5), certain complex pronominals, including adnominal pronouns such as biz Türkler ‘we Turks,’ behave like simplex pronouns in the verbal domain, triggering co-varying agreement (3). However, in the nominal domain, the relevant complex pronominals behave unlike simplex pronouns: they are opaque for nominal agreement when marked with genitive Case (4). We will refer to said complex pronominals as Default Triggering Nominals (DTNs), owing to their capacity to trigger default agreement in sentences like (4); and, for reasons that will become clear below, we will refer to the effect at play in (4) as Relativized Case Opacity.Footnote 1

-

(3)

-

(4)

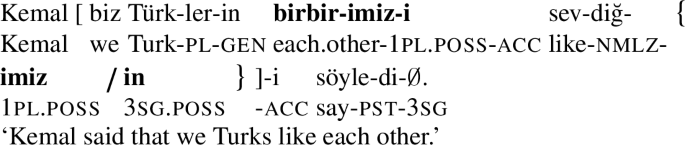

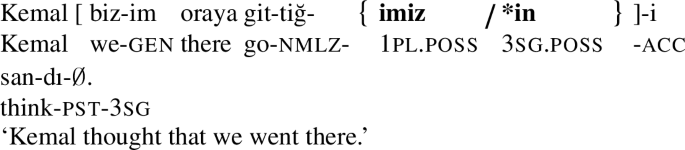

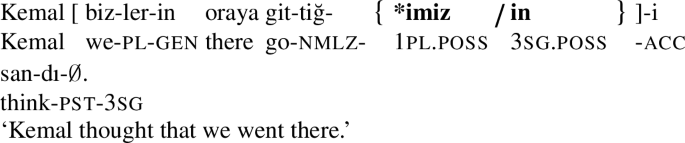

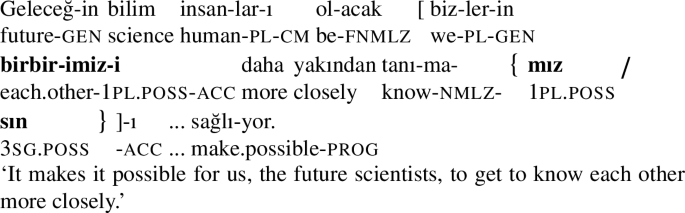

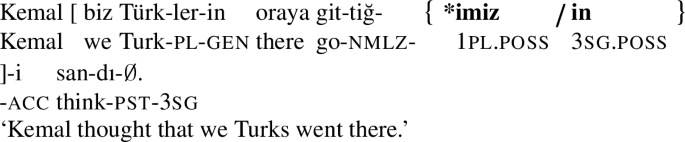

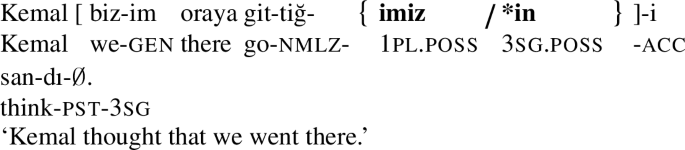

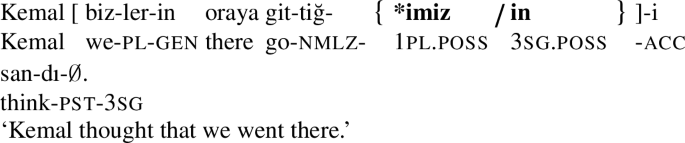

The main empirical focus of our paper comes from the observation that Relativized Case Opacity is overridden under local binding: if a normally non-agreeing genitive-marked complex pronominal locally binds an anaphor or a bound pronoun, it can agree, as in (5). Descriptively speaking, then, local binding licenses an otherwise impossible agreement possibility.

-

(5)

Our first goal is to argue that this striking case of agreement enabled by binding can be readily understood if binding involves the transmission of ϕ-features from the antecedent to the bound element via an intermediate functional head, Voiceminimal (cf. Kratzer 2009; Ahn 2015). Our discussion of the exceptional agreement behavior of DTNs is a further empirical contribution of the paper, and our analysis of Relativized Case Opacity is an additional point of theoretical interest.

The paper’s second goal is to further problematize the details of Agree-based theories of binding. One important question concerns the scope of Agree-based explanation: is Agree implicated in all instances of what has been termed anaphoric binding? We will argue that Turkish allows an empirical window into this question as well, this time motivating a negative answer. Crucial evidence to this end comes from the agreement-related behavior of anaphors embedded in Prepositional Phrases.

The paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 provides some preliminaries on the structure of Turkish nominalized clauses, before establishing the first empirical generalization of interest, Relativized Case Opacity: DTNs fail to control agreement when they are assigned genitive case. We provide an analysis of the structure of DTNs, and demonstrate how it conspires with the conditions under which genitive Case is assigned to lead to a situation of failed agreement. Taking pronouns and larger nominals to differ with respect to how ϕ-features are distributed in their structure, the analysis is based on the standard view that probes, too, can differ in their structure: person and number features on a single head may probe separately (yielding a split probe), or simultaneously (yielding a composite probe). We show how the two points of variation—bundling versus distribution of ϕ-features in pronominal structures, and split versus conjunctive probing in probes—conspire to derive the fact that genitive Case makes only DTNs, but not simplex pronouns, opaque to agreement.

Section 3 begins by introducing the second generalization of interest: case opacity is overridden when DTNs bind, such that a genitive-marked DTN in fact can control agreement, albeit only when it binds. We provide an analysis of this pattern, making crucial reference to the role of ϕ-features in binding. We argue that binding takes place early, before genitive assignment makes the DTN binder opaque. Because binding amounts to ϕ-feature transmission, it leaves its imprint on the structure, in the form of ϕ-features on the maximal projection of the head that mediates the antecedent/bindee relationship. It is these ϕ-features that may be targeted by a higher agreement probe, guaranteeing that co-varying agreement can emerge under binding. We go on to discuss implications of this analysis for the Anaphor Agreement Effect, and for the role of mediating heads in Agree-based theories of binding.

Section 4 considers the Turkish phenomenon in a wider context. We begin by briefly discussing and evaluating other pieces of evidence in favor of the role of Agree in binding, before addressing the question of whether Agree should be implicated in all instances of local binding. Data from binding into Turkish PPs reveals a limited role for Agree, whereby the operation is involved in the binding of arguments, but not adjuncts.

Section 5 summarizes our main points and concludes the paper.

2 Generalization 1: Relativized case opacity

2.1 Preliminaries

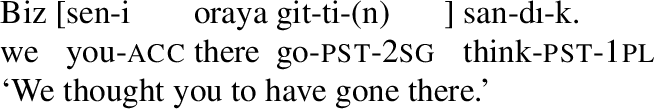

Since much of the discussion to follow revolves around nominalized clauses in Turkish, we provide some background on these here. For more extensive descriptions, the reader is referred to Borsley and Kornfilt (1999) and Kornfilt and Whitman (2011).

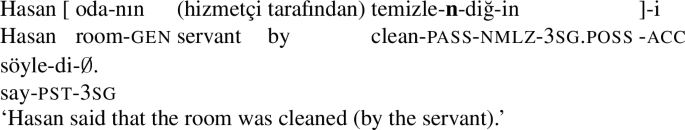

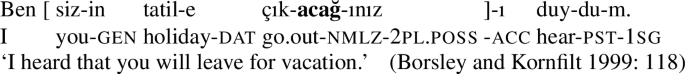

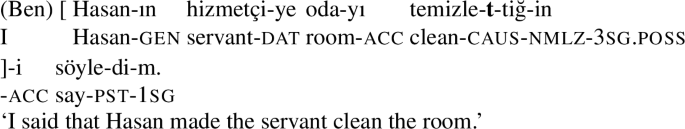

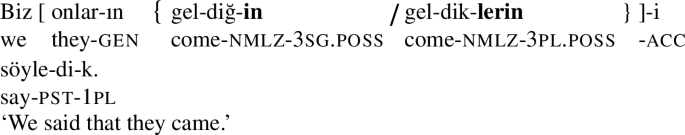

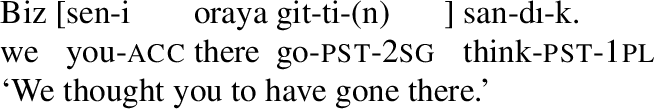

Nominalization is the most common complementation strategy in Turkish (and Turkic more generally; see e.g., Kelepir 2021). The bracketed portion of the example in (6) exemplifies a nominalized embedded clause:

-

(6)

Nominalized embedded clauses in Turkish are characterized by four properties. Firstly, when appearing in argument positions, they are overtly marked for Case by the matrix verb; for instance, in (6), the nominalized clause is marked accusative. Secondly, the embedded subject is marked with genitive Case. Moreover, nominalizing morphemes (tiğ- in (6)) are realized overtly, to the right of the Root. Finally, the nominalized verb agrees with its subject for person and number using the nominal exponents known as the possessive suffixes (e.g. -in above).

Nominalized clauses involve a large verbal/clausal base embedded under a nominal layer. The nominal layer ensures that the clause distributes as a nominal, thus freely appearing in argument positions, and that it receives overt Case-marking; additionally, the nominal layer must be responsible for the presence of the possessive suffixes and of genitive case on the subject, since both properties also appear in possessive NPs which, unlike nominalized clauses, are not verbal in any sense (see (19)–(20) below).

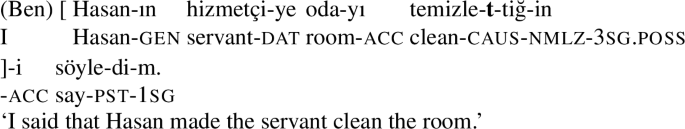

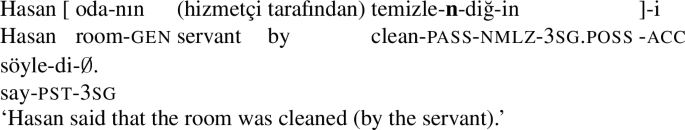

With respect to the size of the verbal base, nominalized clauses clearly embed a full verbal shell. Note firstly that the themes of nominalized clauses freely receive accusative (6). Moreover, these clauses allow the full range of argument structure alternations available in the language, including passives (7) and causatives (8):

-

(7)

-

(8)

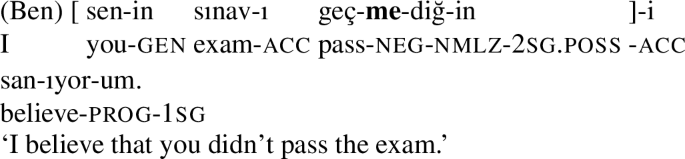

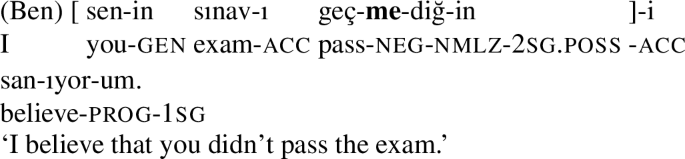

Nominalized clauses can also embed negation:

-

(9)

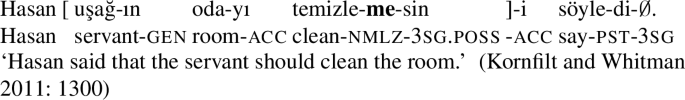

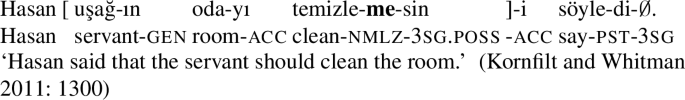

Additionally, the nominalizing morpheme indexes a distinction sometimes referred to as factivity in the literature on Turkish (see Kornfilt and Whitman 2011: 1300; Predolac 2017). Clauses with the nominalizer -DIK as in the examples above are labeled as factive, while those with the nominalizer -mE (10) are labeled as non-factive.Footnote 2

-

(10)

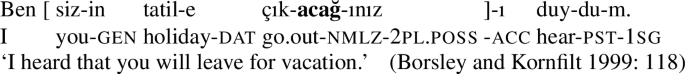

There is a third nominalizer, the so-called future -(y)EcEK.

-

(11)

These different nominalizing exponents can be treated as contextual realizations of the nominalizing morpheme determined by a high verbal head carrying modal features of some sort. What exactly the semantics of these features are, and whether “factivity” and “future” are the correct labels, is orthogonal to our discussion. Note that, since nothing of interest to this paper hinges on the factivity distinction, we do not gloss it in our examples.

We will thus take nominalized clauses to involve a verbal base consisting at the very least of VoiceP, embedded under a layer of nominal projections. The presence of VoiceP is crucial to the analysis to be developed in Sect. 3.2, but nothing hinges on the precise nature of any verbal projections intervening between VoiceP and the nominal layer, which we accordingly omit from our trees for convenience.Footnote 3

2.2 Relativized case opacity

In the Turkish nominal domain, the agreement behavior of simplex pronouns differs from that of a class of complex pronominals which we will call Default-Triggering Nominals (DTNs). Whereas pronominal subjects and possessors trigger co-varying nominal agreement on nominalized verbs and possessed nouns, respectively, DTNs yield default nominal agreement. This section is devoted to describing this agreement asymmetry, and showing that it is governed by the assignment of genitive Case.

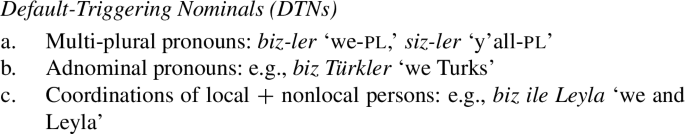

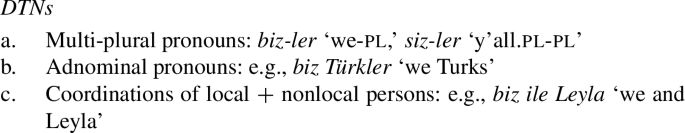

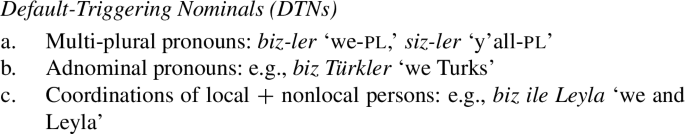

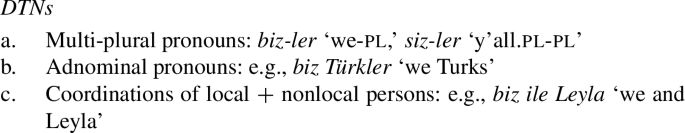

The class of DTNs comprises structurally complex nominal elements that embed a pronoun in their structure.Footnote 4

-

(12)

The agreement-related behavior of DTNs is in fact subject to systematic variation within our pool of consultants; we therefore begin by outlining this instance of variation, before proceeding to outline the pattern that is of interest here.

2.2.1 Preliminaries

Our pool of native Turkish-speaking consultants splits into three groups with respect to the properties of DTNs. For a first small group of speakers (Grammar 1; n=2, approx. 8% of our sample), DTNs are completely on a par with simplex pronouns, triggering full agreement in all environments and thus not being subject to case opacity. A second group of speakers, making up just under half of our consultant pool (n=12, 44%), shows the pattern of relativized Case Opacity, albeit without this configuration being repaired by binding (even though some speakers reported a contrast when the DTN acted as a binder). We refer to these consultants as speakers of Grammar 2. A third variety, the numerically predominant one in our sample (n=13, 48%), is made up of speakers for whom a) DTNs normally trigger default nominal agreement unless b) they bind. It is this variety, Grammar 3, that is the focus of this paper as represented by (3)–(5) above. Unless otherwise noted, judgments henceforth represent those of our Grammar 3-speaking consultants. See footnote 5 for additional notes on the data presented here.

Though our focus is Grammar 3, we touch upon other grammars, especially Grammar 2, when they provide insights. In particular, the analysis in this paper offers a way of understanding the source of the variation in agreement with DTNs. It is likely that speakers of Turkish divide into two groups with respect to the structure they assign to DTNs. As just mentioned above, Grammar 1 speakers seem to be analyzing them on a par with simple pronouns, and thus allowing them to agree; other speakers (Grammars 2 and 3) in turn may posit a more articulated analysis that interferes with agreement, as discussed in this section. We elaborate on the difference between Grammars 2 and 3 in Sect. 3.2.

2.2.2 Data

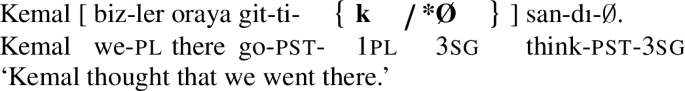

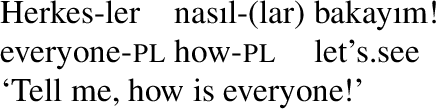

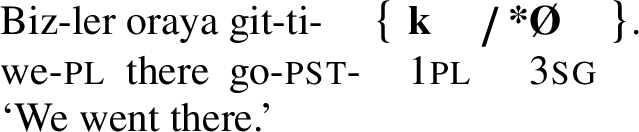

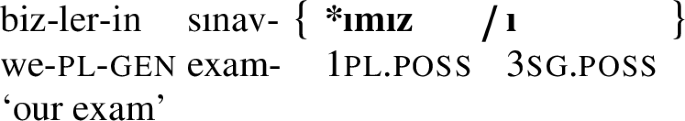

To illustrate the divergent behavior of pronouns and DTNs in the configurations of interest in Grammar 3, we contrast the simplex pronoun biz ‘we’ with its DTN counterpart biz-ler ‘we- ’; the other DTNs (namely, adnominal and coordinate pronouns) behave identically, as we show in Sects. 2.3.4 and 2.3.5.

’; the other DTNs (namely, adnominal and coordinate pronouns) behave identically, as we show in Sects. 2.3.4 and 2.3.5.

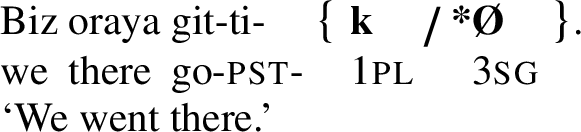

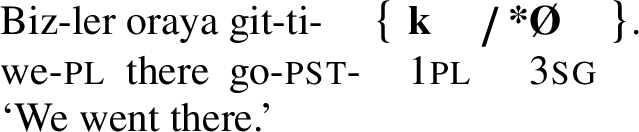

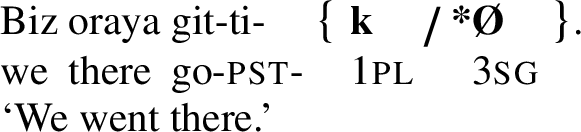

Simplex and multi-plural pronouns pattern together in requiring co-varying agreement in root clauses. In (13)–(14), both pronominal and DTN subjects trigger co-varying first-plural agreement on the verb.

-

(13)

-

(14)

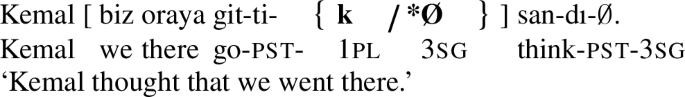

Pronouns and DTNs also pattern together in embedded finite (verbal) clauses. Both exhibit co-varying agreement, as in (15)–(16), similarly to root clauses.

-

(15)

-

(16)

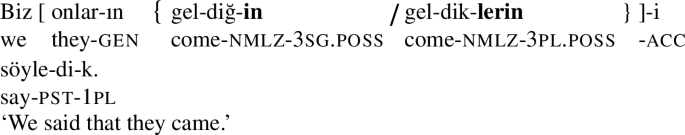

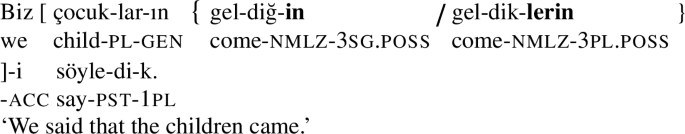

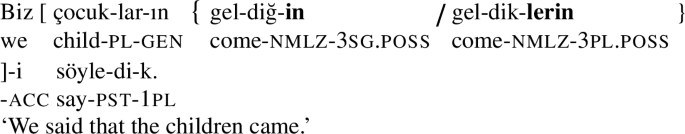

The two, however, diverge in embedded nominalized clauses. (17)–(18) illustrate the basic agreement asymmetry that characterizes Grammars 2 and 3: when in the subject position of an embedded nominalized clause, the pronoun triggers co-varying nominal agreement, whereas the DTN is only grammatical with default third-singular agreement.Footnote 5

-

(17)

-

(18)

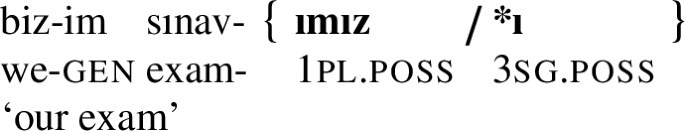

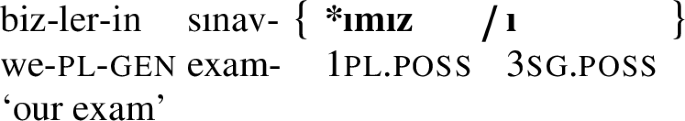

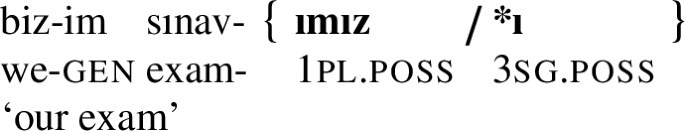

The same asymmetry is found in possessive constructions:

-

(19)

-

(20)

In (19)–(20), the possessors are in the genitive, much like the embedded subjects of (17)–(18). In (19), the possessum agrees with the pronominal possessor for person and number; but in (20), with a DTN possessor, the possessum can only show default third-singular agreement. Note that, although nominal agreement is hosted on nominalized verbs in (17)–(18) but on simple root nominals in (19)–(20), the agreement exponents are the same in both cases.

Table 1, to be revised, summarizes the observations made thus far. For the purposes of verbal agreement, pronouns and DTNs pattern together, obligatorily triggering full agreement. But under nominal agreement, pronouns and DTNs dissociate: the former continue to trigger full agreement, while the latter are only grammatical with default third-singular agreement.

This difference between nominal and verbal clauses correlates with the Case assigned to the subject of each. Notice that the subjects of verbal clauses (13)–(16) receive unmarked/nominative Case, whereas the subjects of nominalized clauses (17)–(18), like possessors (19)–(20), receive genitive. It is the genitive that blocks nominal agreement with DTNs, but not with pronouns.

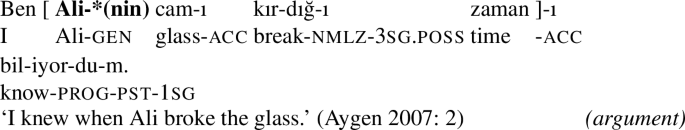

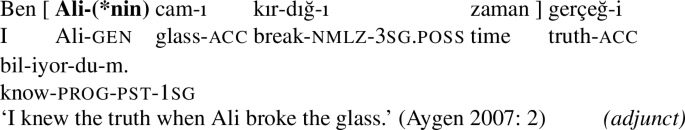

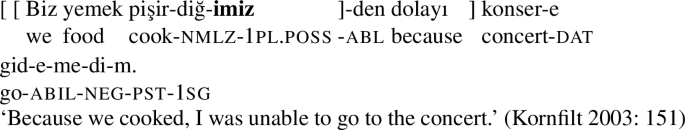

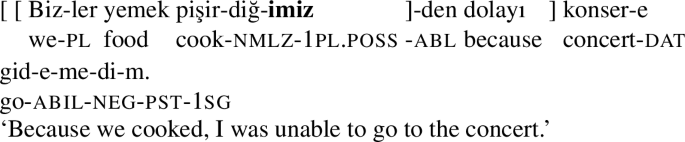

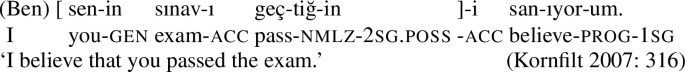

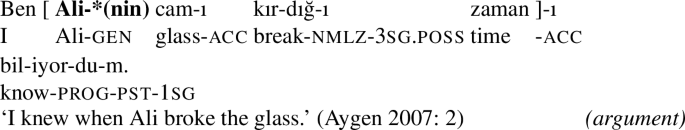

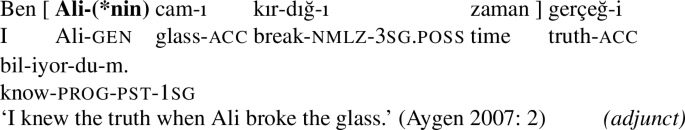

Evidence for this crucial involvement of Case comes from an asymmetry between adjunct and argument nominalized clauses. As Kornfilt (2003) observes, the subjects of argument nominalized clauses are in the genitive, but those of adjoined nominalized clauses are in the nominative:

-

(21)

-

(22)

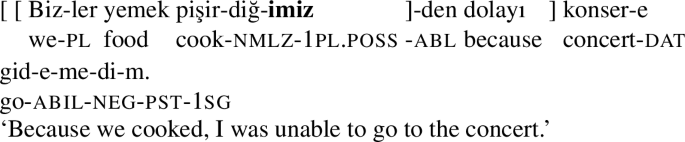

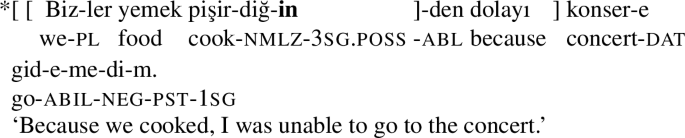

In (21), the nominalized clause functions as an embedded question in the object position of the matrix verb, and its subject is in the genitive, paralleling all examples seen so far. But in (22), where the nominalized clause is a temporal adjunct to the main verb, its subject must be nominative.Footnote 6

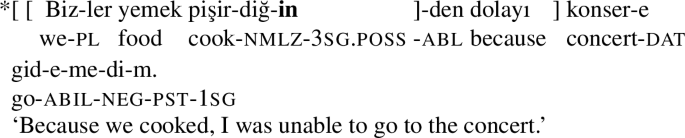

This contrast between argument and adjunct nominalized clauses provides an ideal testing ground for the role that subject Case plays in determining agreement. Let us contrast the behavior of pronouns and DTNs in the subject position of adjunct nominalized clauses:

-

(23)

-

(24)

In (23), the nominative pronominal subject of the nominalized clause triggers co-varying agreement on the nominalized verb. This is expected, given that pronouns always trigger co-varying nominal agreement, even when marked with the genitive (17). Crucially, the nominative DTN subject in (24) also triggers co-varying nominal agreement. In fact, nominative DTN subjects of nominalized clauses must trigger co-varying agreement, as the contrast between (24) and (25) shows:

-

(25)

We thus observe that the agreement-related behavior of DTNs is determined by the Case assigned to them. When a DTN bears nominative, its ϕ-features are accessible for agreement: this is the case in verbal clauses (14)/(16) and adjunct nominalized clauses (24). But genitive Case blocks agreement with DTNs: this is why DTNs cannot trigger co-varying agreement in argument nominalized clauses (18) and possessive constructions (20). Pronouns differ from DTNs in that they can be agreed with both when marked nominative and when marked genitive. Table 2 summarizes this state of affairs, revising the preliminary description of Table 1 into the correct generalization that makes explicit reference to Case.

We follow Rezac (2008) in using the term Case Opacity to refer to situations where Case assignment to a nominal prevents that nominal from triggering co-varying agreement. The facts discussed so far are noteworthy insofar as they constitute an instance of Case Opacity that is relativized: genitive Case blocks agreement when assigned to DTNs, but not to simplex pronouns.Footnote 7

-

(26)

Generalization 1: Relativized Case Opacity

Genitive Case makes DTNs, but not pronouns, opaque for agreement.

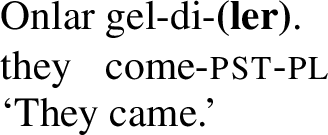

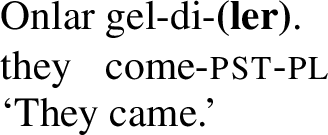

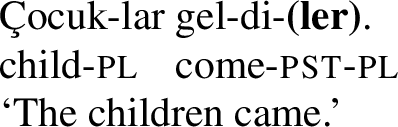

Finally, note that the agreement behavior of pronouns contrasts with that of DTNs specifically, and not of larger DPs more generally. This is clearly seen with third-plural DPs, which pattern with pronouns, not DTNs. It is a general fact about the language that overt third-plural DPs optionally trigger plural agreement on the verb:

-

(27)

-

(28)

Plural agreement continues to be possible in the examples (29)-(30), which are the nominalized counterparts of (27)-(28), respectively:Footnote 8

-

(29)

-

(30)

If third-plural pronouns and common nouns patterned with DTNs, (third-)plural agreement should be ungrammatical in (29)–(30), contrary to fact. As such, the correct generalization is that pronouns and common nouns pattern together to the exclusion of DTNs: the only nominals that fail to control agreement when marked with genitive are DTNs. More specifically, default agreement arises when the agreement controller is a) a local person pronoun embedded in a larger nominal structure (i.e., a multi-plural, adnominal, or coordinated local person pronoun) that is b) marked with genitive.

The focus of the paper is the binding/agreement interaction, which we describe and analyze in Sect. 3. However, before proceeding with that investigation, we discuss the internal structure of DTNs, and provide an analysis that correctly distinguishes DTNs from pronouns with respect to their agreement behavior. We take care to do justice to the properties of individual DTN constructions while trying to give an overarching analysis that can apply to all three types of DTN. This analysis will provide enough of a scaffolding to support our ensuing analysis of the binding/agreement interaction, though the latter is not necessarily dependent on the details of the former.

2.3 Understanding relativized case opacity

Understanding relativized case opacity in Turkish amounts to understanding the interplay of two seemingly unrelated factors. The first is genitive assignment: on the one hand, agreement is blocked in environments where the genitive is assigned. On the other hand, this cannot be the only factor at play: if it were, both pronouns and DTNs would be opaque when marked with genitive, contrary to fact. We thus also need an account of the internal structure of simplex pronouns and DTNs, one that explains why the former agree both when nominative and when genitive, while the latter only agree when nominative.

In this section, we examine each of these two factors in turn.

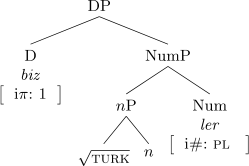

2.3.1 Ingredient 1: The structure of (some) DTNs

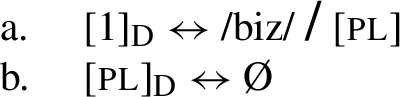

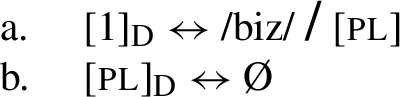

We begin by developing the intuition that pronouns and larger nominals differ crucially with respect to how ϕ-features are distributed in their structure (cf. Ghomeshi and Massam 2020). For (local) pronouns, we posit that these involve bundling of interpretable person and number features on a single head, which we will label D (cf. footnote 24) along the lines of (31). This bundle is realized as in (32a): effectively, biz is the contextual realization of first person when the first person feature is local to number. In (31), first person and plural number are as local to each other as they can be; namely, they are on the same head. The plural feature itself is unrealized when on D, (32).Footnote 9

-

(31)

-

(32)

For common nouns, we adopt the structure in (33), which consists of a root, the categorizer n, and a number head, Num (Ritter 1991; Moskal 2015). Following one standard analysis of third person nominals (Kayne 2000; Harley and Ritter 2002; Béjar 2003; Anagnostopoulou 2005; Adger and Harbour 2007; Béjar and Rezac 2009; among many others), we assume that they lack person altogether; as such D (and its person feature iπ) is absent, and only i# is available on the Number head, which if plural is spelled out as -lAr, shown in (34).

-

(33)

-

(34)

[

]num ↔ /lAr/

]num ↔ /lAr/

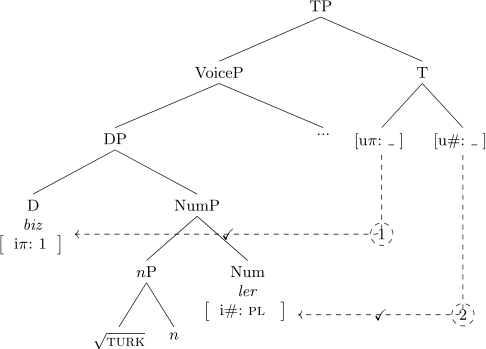

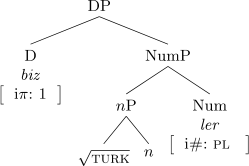

On the other hand, the structure of multi-plural pronouns and adnominal pronouns involves a pronominal determiner introducing a more articulated nominal structure, with ϕ-features distributed throughout this larger structure (see e.g. Moskal 2015 for one concrete proposal regarding the distribution of features across nodes in the nominal domain). On this view, simplex pronouns and DTNs crucially differ along one dimension: whereas in pronouns ϕ features are bundled on the same head, in DTNs the features are distributed over more than one head.Footnote 10 We begin by developing this intuition for multi-plural pronouns and adnominal pronouns, reserving discussion of coordinate pronouns for Sect. 2.3.5.

Beginning with multi-plural pronouns, any account of their structure must begin from whether their semantics differs from that of simple pronouns. To our knowledge, no such difference exists.

Pairs like biz and bizler do not differ in terms of clusivity; they also do not differ in terms of collectivity/distributivity, unlike the associative plurals of Turkish (Ketrez 2010: 179).Footnote 11 The difficulty in discerning a clear semantic contribution for -lAr in bizler is reflected in claims that the plural exponent on pronouns is optional, found in the typological literature on Turkic (see Nevskaya 2010: 123–124 for a brief survey). Some speakers report that multi-plural pronouns have a more “emphatic” role, whose exact status, however, is hard to discern.Footnote 12

As also pointed out by an anonymous referee, forms like bizler are marked for most speakers and in fact are considered substandard by some. However, apart from their pragmatic markedness, we do not believe that multi-plural pronouns have a different interpretation than simple pronouns. Prescriptive statements concerning the use of bizler in fact often use the lack of a interpretive difference between the two to justify the labeling of bizler as “redundant.”Footnote 13 Such statements, we believe, are strong indications that the markedness of bizler is due to its being perceived as an alternant of biz, one that is redundant precisely because it is referentially equivalent to the simple pronoun.Footnote 14

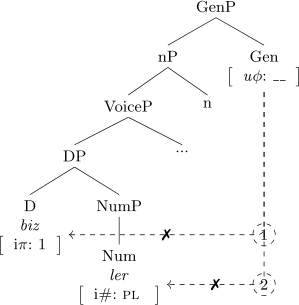

It is likely, then, that forms like bizler are “doubly plural” only in form, but not in meaning. We implement this intuition by assuming that, alongside being bundled together on the same head (31), there is an additional possibility regarding the structuring of person and number features: they can be contributed by separate nominal heads. As such, the D head in (35) differs from the one in (31) with respect to its feature make-up: while the pronoun in (31) carries both person and number features, the pronominal determiner in (35) is specified for person only. The number feature is then contributed by a separate head Num. For the purposes of interpretation, this structure guarantees that the resulting nominal is a plural pronoun like any other: the structure in (35) has one interpretable person feature and one interpretable number feature, just as (31) does. But the fact that the features are distributed in (35) guarantees a different realization compared to (31). (32a) will still apply to insert biz on D, since the person feature is local to number (this time, number is on a separate head, albeit one that will always be adjacent to D, both linearly and structurally). But since the number feature is now located on Num, (34) can apply, inserting -lAr.Footnote 15

-

(35)

In other words, because there is only one interpretable number feature in the structure, (35) is not interpreted differently to (31); but because the independent number feature of (35) acts both as the context for insertion of biz and as the target for insertion of -lAr, we get the superficial appearance of two instances of plurality at the point of exponence.

We consider this analysis to be simple and parsimonious. In particular, given the existence of two independent features, it might be the null hypothesis that they will be able to occur either bundled or separately on independent heads; from this perspective, Turkish does no more than attest both options in its pronominal system. The same may be true in other languages with double-marking of number of the relevant sort (Ghomeshi and Massam 2020: 601ff.).

In fact, in positing two ways of relating person and number—bundling vs. independent projection—we build directly on and extend the insights of Ghomeshi and Massam (2020), who argue on a cross-linguistic basis that number is projected independently in full nominals, leading to the semantics of individuation, but not in pronominals, where number is structurally subordinated to person. We take the wide-ranging differences between regular nominal and pronominal number discussed by Ghomeshi and Massam to be supportive of this conjecture, and add Turkish to their typology: as we will see, in Turkish, bundling (31) versus independent projection (35) lead not just to different distributions, but to the distinct agreement behaviors of pronouns versus DTNs.Footnote 16

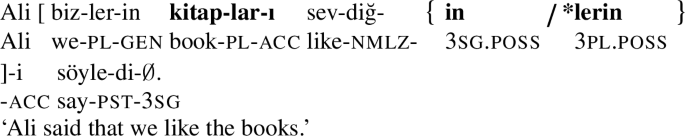

Consider now adnominal pronouns like ‘we Turks.’ These elements show the same behavior as other DTNs, as illustrated in (36) and (37): in the verbal clause in (36), the adnominal pronoun triggers co-varying agreement, whereas it fails to do so in the nominalized clause in (37).

-

(36)

-

(37)

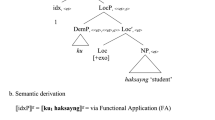

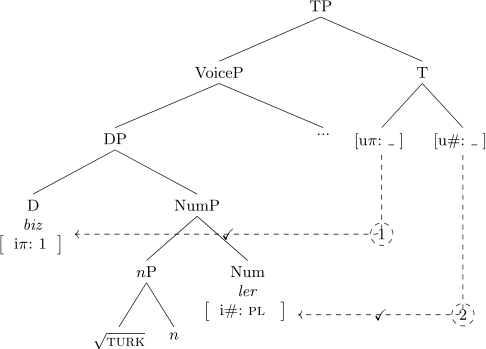

Adnominal pronouns can be straightforwardly incorporated into the structure in (35): these involve an additional lexical layer below the functional projections for person and number, as in (38) (e.g. Höhn 2016, 2020; Satık 2020).Footnote 17

-

(38)

2.3.2 Ingredient 2: The structure of probes

With the structure of DTNs in place, the second ingredient of our analysis of Relativized Case Opacity concerns the nature of Case assignment in the nominal versus the verbal domain. A first crucial assumption involves the nature of the structures where nominative and genitive Case are assigned. Following Kornfilt and Preminger (2015), we take nominative to correspond to syntactic Caselessness: nominative is unmarked in the deep sense, in that it corresponds to the lack of Case on a nominal. This type of solution is fully consistent with the fact that the exponence of nominative in Turkish and related languages is systematically null.

The prototypical nominative-bearing context is thus schematized in (39): the verbal agreement probe T bears no Case feature whatsoever, and the Agree operation between T and the closest DP results in valuation of the former’s unvalued uninterpretable ϕ-features without Case assignment to the nominal.

-

(39)

Recall from (22)–(24) that nominative can also be present in embedded nominalized clauses, where the agreement suffixes are not those that would realize T in (39), but are rather drawn from the Turkish nominal agreement paradigm. We take the relevant exponents to realize a distinct probe Poss (e.g., Kornfilt 1984, 1997; Arslan-Kechriotis 2006, 2009; Kunduracı 2013), which is effectively the nominal counterpart of T. In adjunct nominalized clauses, then, where the subject is realized as nominative/unmarked, the structure is of the following type, abstracting away from any additional verbal layers between Voice and the nominalizer n.

-

(40)

What about the arguably more frequent case, where the subject of the nominalized clause is genitive? Recall that we need these clauses, too, to be realized with the nominal agreement suffixes; in other words, Poss must be present here, too. What about the Case-marking of the subject? Clearly, genitive cannot be assigned by Poss, since Poss is present in (40) as well; in other words, genitive Case assignment does not go hand in hand with nominal agreement, therefore genitive Case assignment cannot be tied to the presence of the head responsible for nominal agreement. Recall that in adjunct nominalized clauses, as shown in (22), the two functions are dissociated in that nominal agreement obtains in the absence of genitive. As such, when genitive is assigned, namely, in argument nominalized clauses, a different head (call it Gen) must be responsible for this function. This assumption vis-à-vis the state of affairs in (39)-(40) is, we believe, straightforwardly tied to the fact that nominative in Turkish is always morphologically null, but genitive never is. See Satık 2020 for the same dissociation in Turkish (as well as Kornfilt 1984; Arslan-Kechriotis 2006; cf. Lim 2022 for further evidence from Khalkha Mongolian).

We further assume that, although agreement can take place without Case assignment, as in (39), Case assignment must be accompanied by an instance of Agree; in other words, Case-assigning functional heads are probes. More precisely, we assume that once a Case is assigned, an Agree operation is triggered; though this cycle of Agree is obligatory, it need not be successful (Preminger 2014), and because the assignment of the Case feature precedes the initiation of the Agree operation, whether Agree fails or not has no bearing on the success of Case assignment.

Applied to the structure we have been sketching, the assumption that Case assignment is accompanied by a later operation of Agree entails that Gen, the genitive-assigning head, bears unvalued ϕ features, as in (41). These features will initiate a cycle of Agree; if this operation is successful, Gen will copy the DP’s ϕ features, and Poss will subsequently inherit those same ϕ features from Gen, which is the closest goal to Poss. If Gen fails to acquire the DP’s ϕ features for whatever reason, then Gen will also be unable to transmit these ϕ features to Poss. We further assume that Gen and Poss are phase heads: when Poss is merged, the complement of Gen is spelled out. As such, Poss cannot probe the DTN directly, and Gen is effectively the only possible goal for Poss (see Bhatt 2005; Bhatt and Walkow 2013 for a very similar type of dependency between multiple functional heads, e.g., T and Asp, in terms of uninterpretable ϕ-features in Hindi-Urdu).Footnote 18

-

(41)

From this perspective, the differences between agreement in the verbal versus the nominal domain are as follows: although nominative corresponds to Caselessness, genitive is assigned by a functional head distinct from the agreement probe (recall that this is empirically motivated by adjunct nominalized clauses, which have nominal agreement but lack genitive Case). As a result, in argument nominalized clauses, agreement is mediated: when Gen is present, Poss can never agree with the subject DP directly, and can instead only agree with Gen.Footnote 19

We can now begin to glimpse the gist of our solution to the puzzle of relativized Case Opacity: it hinges on the role of Gen. We will argue that, in a structure like (41), the ϕ probe on Gen can be valued by the features of DP when DP is a simplex pronoun, but not when it is a DTN. When the DP is a pronoun, Gen will receive its ϕ features, and Poss will subsequently receive the same ϕ features when it probes  ; but when the DP is a DTN, it must be the case that Gen, and thus Poss, cannot receive any ϕ features, leading to the emergence of default agreement. We thus continue by elaborating on why Gen cannot be valued by DTNs.

; but when the DP is a DTN, it must be the case that Gen, and thus Poss, cannot receive any ϕ features, leading to the emergence of default agreement. We thus continue by elaborating on why Gen cannot be valued by DTNs.

Recall from the immediately preceding section that pronouns and DTNs differ with respect to how ϕ features are organized in the nominal structure. When person and number are bundled on the same head, the result is a simplex pronoun; when the same features are distributed over the nominal structure, with number being contributed independently from person, the result is a DTN, as illustrated above with multi-plural and adnominal pronouns. In the rest of this section, we take this difference in the organization of ϕ features to be responsible for the differential behavior of pronouns and DTNs when they interact with the Gen probe. The aim is to lend substance to the intuition that this section began from, namely, that relativized Case Opacity follows not from either the assignment of genitive or the structure of DTNs alone, but from the interaction between these two factors.

To implement this intuition, we draw a crucial distinction regarding the nature of features on probes. Note that, in (41), we represent the probe on Poss as two distinct person and number features, but we represent Gen with a single composite ϕ probe. This notational difference is intentional: heads may bear distinct (split) probes for person and number, or a single conjunctive (or composite) probe, such that person and number probe together. Both options have been independently proposed in the literature (e.g., Béjar 2003; Béjar and Rezac 2009; Coon and Bale 2014; Preminger 2014; Van Urk 2015), with many studies gaining syntactic mileage out of the difference between split and conjunctive probing. For instance, Coon and Bale (2014) argue that Agree may sometimes involve multiple features, which happen to be person and number in Mi’gmaq (an Algonquian language), acting as a composite probe.Footnote 20

Given that both types of probes have been argued to be available, we expect that languages may choose to treat distinct probing features on one head as composite or separate (see also e.g. Martinović 2022 for this idea implemented to Wolof). We propose that both options are available in Turkish, and that the choice between them is furthermore relativized to the nature of the head on which these features are located. Specifically, on dedicated agreement probes such as T and Poss, which are the verbal and nominal counterpart of each other, π and # function as separate probes (following Ince and Aydın 2015); but on the case-assigning head Gen, they form a conjunctive, bundled probe. We will use the notational convention in (42) to reflect this difference, representing split probes using separate branches for person and number solely for expository purposes; when space prohibits this type of representation, we will notate split probes as separate [uπ: __] and [u#: __] features under the same node, again to be distinguished from the composite [uϕ: __].

-

(42)

Person and number will thus probe separately when found on T or Poss, but will act as one probe when on Gen. Adopting Cyclic Agree, and following Béjar (2003, 2008) and Béjar and Rezac (2009), we take it that Agree is subject to the condition that in each cycle of search, a probe must find a goal that exhaustively matches its specifications in order to be valued. Agree will thus fail when the feature structure of the goal is less specified than that of the probe. More specifically, in the case of partial matching, where only a proper subset of the features that the probe needs are available on the goal, the probe does not copy any features (see also Adger 2010). However, this failure to be valued does not lead to a crash, with unvalued features surviving to PF, where they receive a default value (Preminger 2014).

Coupled with the postulation of split versus composite/conjunctive probes, the no-partial-copying condition on Agree plays a crucial role in explaining why DTNs trigger default agreement in the domain of the Gen head, but full agreement elsewhere. Let us begin illustrating the analysis with simple pronouns and common nouns, before turning to DTNs.

Simple pronouns will be able to satisfy both split and conjunctive ϕ probes. In pronouns, interpretable π and # features are bundled on the same D head. The split probes will probe successively, and each will find its matching feature on D. Importantly, the more stringent conjunctive probe, which requires that its goal bear both interpretable person and interpretable number, will also be satisfied, since person and number are bundled in pronouns. This situation is schematized below. In (43), each of the split probes of T have found their matching feature on the pronoun; in (44), Gen has successfully acquired the pronoun’s features, and Poss, by probing Gen, will successfully acquire them as well.Footnote 21

-

(43)

-

(44)

Adjunct nominalized clauses would have the structure in (44), but without Gen; as such the uπ and u# features on Poss would directly probe their matching interpretable counterparts on D.

Note a crucial assumption necessary to derive the correct realization of nominal agreement: in nominal structures like (44), there can be two valued probes (namely, Gen and Poss), but we only ever find one set of ϕ features realized on the nominalized verb. It must be the case, then, that ϕ features on Gen are never realized. We leave open the exact mechanism that guarantees this, noting that a post-syntactic rule such as Impoverishment would have to be responsible.

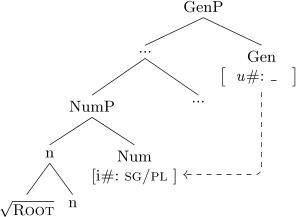

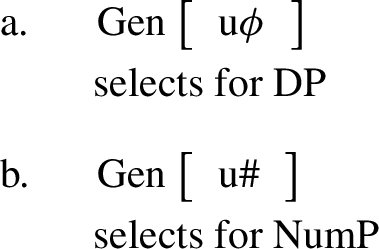

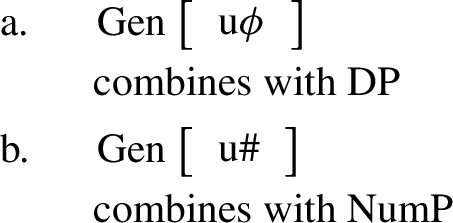

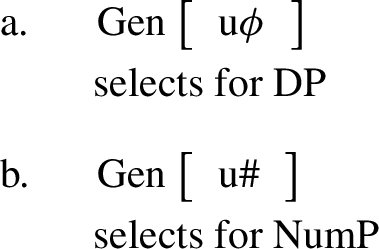

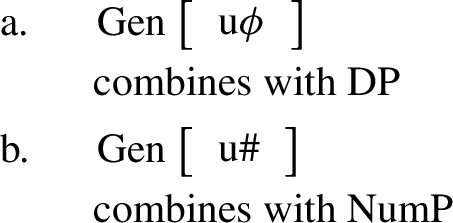

Before turning to DTNs, and to contextualize that discussion, we first detail the behavior of common nouns. Recall that common nouns (as well as third person pronouns) also trigger full agreement in nominalizations. To capture the contrast between local persons, as found in DTNs, and non-local persons, we enrich the featural content of Gen, noting that in addition to the composite [uϕ] probe, it can also bear only the [u#] feature. The choice between the different featural contents of Gen depends on the nominal it combines with, and we implement this relationship as a selectional restriction.Footnote 22

Relevant to our purposes is that the Gen head bearing the conjunctive [uϕ] selects for a DP, a goal that contains the interpretable person feature. Therefore, in the context of a DP, the Gen head with the conjunctive probe is inserted. The Gen head with the sole [u#] feature combines with NumP, which we use as a shorthand for phrases that lack the person feature (which, in the privative person system we assume, correspond to third person).Footnote 23 As such, in the context of common third-person nouns, the Gen head will simply have the [u#] feature, (45). Note that this is in line with a commonly assumed entailment relationship between ϕ-features: the presence of person entails number, but not the other way around (Harley and Ritter 2002; Béjar 2003; Béjar and Rezac 2009; Coon and Bale 2014; Deal 2022, i.a.). This guarantees it is impossible to have a probe (Gen or another) with a person feature but not a number feature, which crosslinguistically seems to be a correct prediction, as the aforementioned studies also demonstrate.

-

(45)

To summarize, the Gen head can host either a conjunctive probe or only a number probe, and these probes are inserted in different contexts. The conjunctive probe selects for a DP, whereas the Gen head with only the [u#] feature selects for NumP, as shown in (46).Footnote 24 As we will demonstrate shortly, this assumption proves instrumental in understanding the intricate behavior of coordinate pronouns, bringing them in line with the other DTNs.

-

(46)

Given this background, we now turn to DTNs. We will examine the DPs making up this class in turn; these are listed in (12), repeated here as (47).

-

(47)

2.3.3 Multi-plural pronouns

Coupled with the structure of probes developed in the previous section, the structure of multi-plural pronouns, where person and number are contributed by different heads, guarantees that these trigger full agreement in the verbal domain, but default agreement in the nominal domain. Let us illustrate first with the derivation of full agreement in finite clauses. On the T head, uπ and u# probe separately, and both independently find their full match. The person probe finds the interpretable person feature on D, and the number probe the number feature on Num. These derivational steps are sketched in (48). The combination of first person and plural features on T will be spelled out as the  affix -k at PF.

affix -k at PF.

-

(48)

Consider now the behavior of multi-plural pronouns under the nominal probes Gen and Poss. Since it is merged with a DP, Gen will have the conjunctive probe, with person and number probing together. As such, when Gen probes, only a goal that has both π and # bundled on the same head can value it. This condition imposes a strong restriction: there is no way to value the conjunctive probe in this structure. Assume that the conjunctive probe finds the closest goal, which will be the iπ feature on D. Since D contains only a proper subset of the features needed to value the Gen head, Gen cannot be valued. A second cycle of Agree is initiated, but also fails to value the Gen head. The reason is that Num, the next available goal, only contains i#, and not both of the features needed to value the probe. Since both cycles of the search fail, Gen will remain unvalued. This derivation is sketched in (49).Footnote 25

-

(49)

By the time Poss enters the structure, as shown in (50), the complement of Gen will have been spelled out. Since the only available goal, Gen, is empty, Poss will itself not be valued, and will receive default third singular values at PF (Preminger 2014).

-

(50)

2.3.4 Adnominal pronouns

The derivation of adnominal pronouns will proceed in the same way as with the multi-plural pronouns just discussed. When T probes, each part of the split probe will find its interpretable feature counterpart on a different head, as shown in (51) (cf. (48)).

-

(51)

Consider now the derivation when the probe is Gen, (52), before Poss is merged. In the first cycle, the conjunctive probe will fail to find both person and number as the D head only contains the interpretable person feature; the second cycle of probing will have the same fate, since Num only carries a number feature. Thus, in neither cycle of the search does the goal exhaustively match the specification of the conjunctive probe, causing Gen to remain unvalued. Similar to the situation with the multi-plural pronouns, by the time Poss enters the structure in a later stage of derivation, the complement of Gen will have been spelled out; therefore, Poss will itself not be valued, and will receive default third singular values at PF.

-

(52)

Overall, multi-plural pronouns and adnominal pronouns involve very similar derivational steps and trigger default agreement for the same reason.

2.3.5 Coordinate pronouns

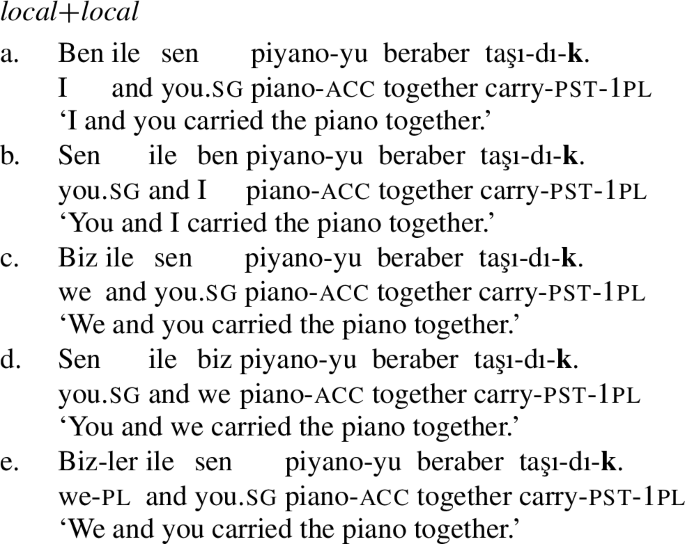

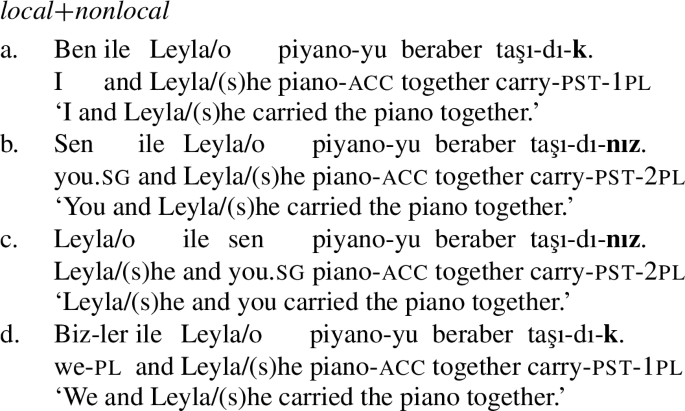

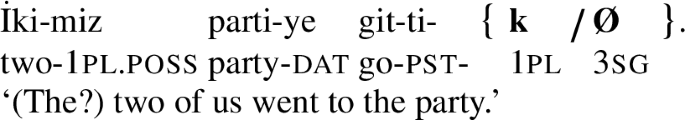

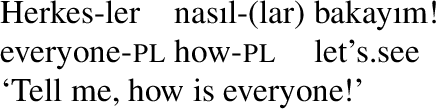

The final DTN comes in the form of certain coordination patterns, e.g. biz ile Leyla ‘we and Leyla.’ Like the other DTNs, coordinate pronouns trigger full (resolved) agreement in finite clauses, and default agreement in the nominal domain. But their behavior shows certain further intricacies: default agreement occurs only in certain combinations of conjuncts, namely, only in conjunctions of local and non-local persons. We will show how these more complex patterns emerge as natural consequences of our system as developed thus far.

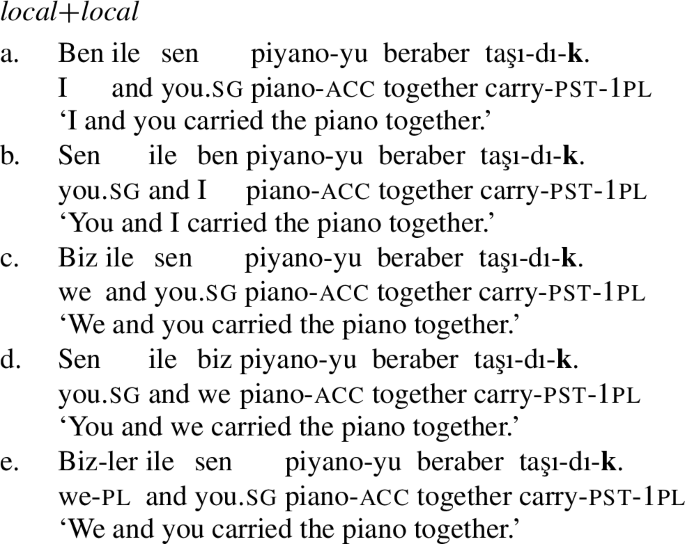

We first introduce the patterns we find in finite clauses (matrix and embedded) with various person combinations which are representative of the overall paradigm in coordination (leaving out some number combinations and conjunct orders since number resolution consistently leads to plural, and the order of conjuncts has no effect). The examples in (53) through (55) replicate the person hierarchy noted for copular structures in Turkish (Ince and Aydın 2015), as follows.

Combinations of local persons (1+2, or 2+1) trigger resolved first-plural agreement (53).Footnote 26

-

(53)

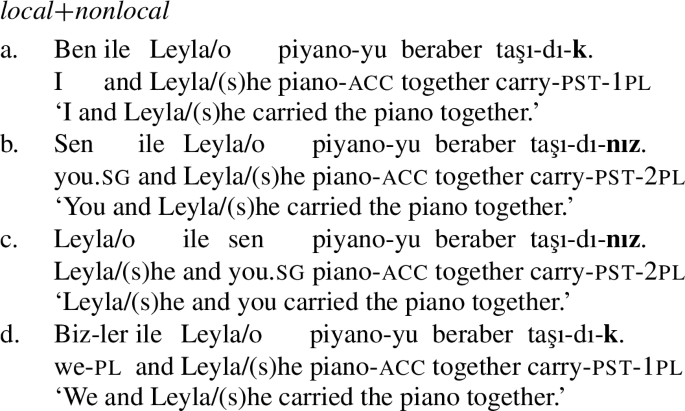

When local persons combine with nonlocal persons (1/2+3, or 3+1/2), the local person feature is realized (54).

-

(54)

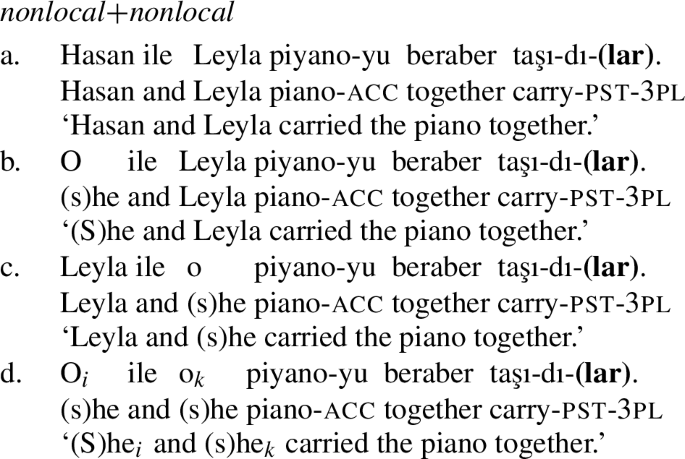

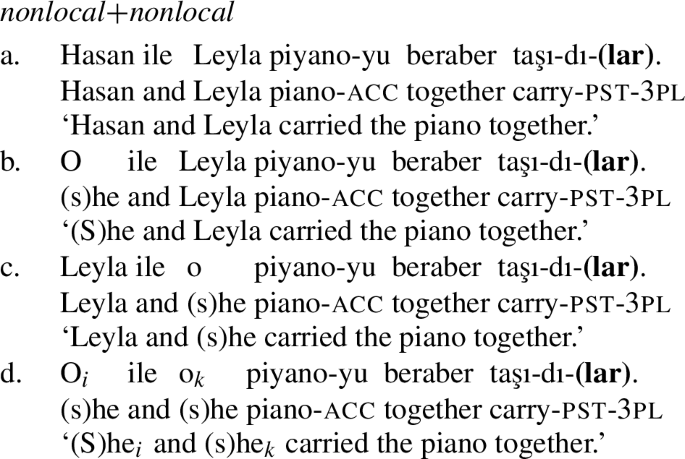

Finally, when nonlocal persons are coordinated (3+3), they trigger optional third plural agreement, (55) (see fn. 8 for this optionality in Turkish).

-

(55)

These patterns demonstrate that in the verbal domain, agreement resolution rules in Turkish are unremarkable in that they replicate the patterns commonly observed crosslinguistically: 1&2>1, 1&3>1, 2&3>2, 3&3>3, irrespective of the order of conjuncts. The interesting pattern arises when we examine coordination in the nominal domain.

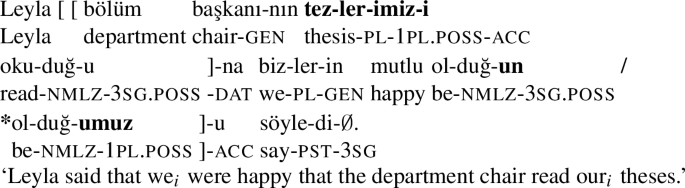

Let us thus turn to nominalized clauses; these for the most part parallel the behavior observed in root clauses, and we thus provide the nominal counterparts of a representative subset of (53)–(55). Combinations of local persons trigger first plural agreement (56), and conjunction of nonlocal persons triggers optional third plural agreement, as in (57).

-

(56)

-

(57)

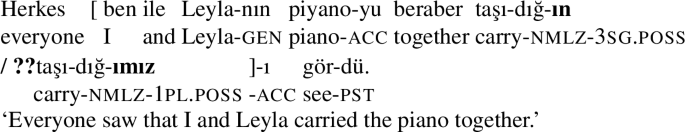

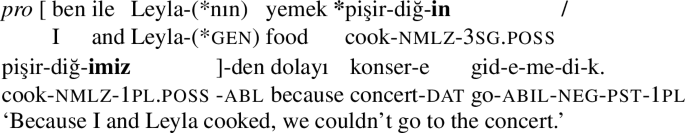

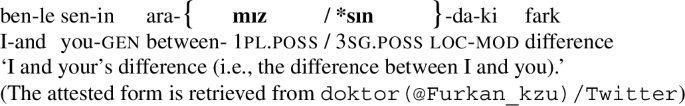

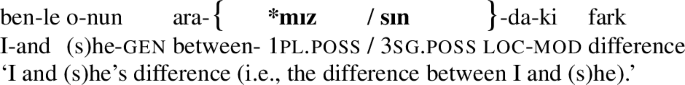

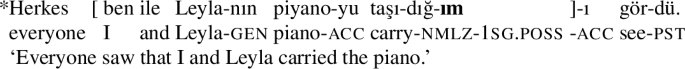

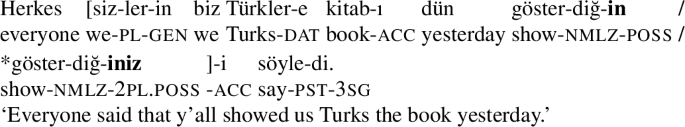

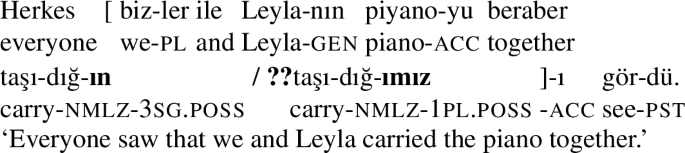

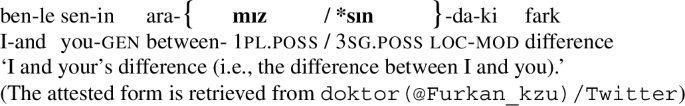

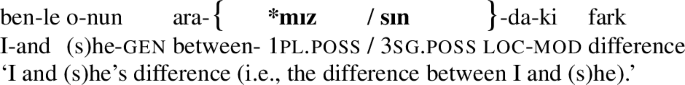

The striking contrast between verbal and nominal clauses is seen when we consider combinations of local and non-local persons, e.g., a coordinate phrase like ‘I and Leyla/she.’ While this coordination triggers first plural agreement for all speakers in verbal clauses (cf. (54)), for speakers of Grammar 3, the same phrase fails to trigger resolved agreement when it is the subject of an argument nominalized clause, as shown in (58) and (59).Footnote 27,Footnote 28

-

(58)

-

(59)

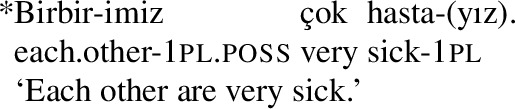

As with the other DTNs, when coordinate pronouns are nominative subjects of adjunct nominalized clauses, they do agree:

-

(60)

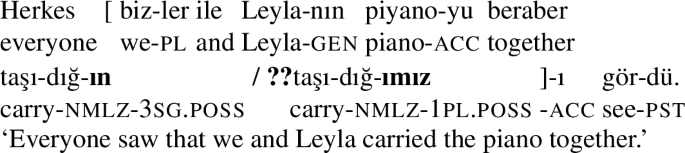

The patterns thus far are significant for several reasons. They make it clear that the factor responsible for default agreement with coordinate pronouns is not coordination itself, since resolved agreement is possible in many combinations of conjuncts even with the Gen head. Rather, resolved agreement is disallowed in a particular set of circumstances, namely, when a local and a nonlocal person are conjoined.

A satisfactory analysis should do justice to the subtleties inherent in the facts discussed here. The approach we sketched above, involving insertion of a Gen probe with a certain featural content, depending on the nominal it combines with, plays a crucial role in explaining the interesting behavior of local+nonlocal coordination. (61) repeats (46), stating that when Gen selects a DP, which has both person and number features, it hosts the conjunctive probe [uϕ]. On the other hand, when Gen combines with a phrase that lacks the interpretable person feature, but has only number, its probe is specified as [u#].

-

(61)

To preview our analysis, we suggest that selection of the featural content of Gen in coordination proceeds as follows. If either of the conjuncts is a DP (i.e. is a local person nominal), the Gen head with the conjunctive probe [uϕ], (61a) will be inserted. Otherwise, the Gen head bearing just the u# will be inserted, (61b). The presence of a DP in one of the conjuncts will trigger the insertion of the conjunctive probe. This probe will be valued by the DP conjunct, but will not be able to be valued by the NumP conjunct, leading to non-resolution and, ultimately, insertion of default third-singular values. This way, the system incorporates the ingredients and mechanism employed for other DTNs, and attributes the emergence of default agreement with local+nonlocal coordination to a problem of non-resolution that arises when we attempt to coordinate ‘unlikes.’ This state of affairs helps explain why default agreement is triggered only in combinations of local and non-local conjuncts: the intuition of the analysis below is that local+nonlocal coordination leads to default agreement because the probe cannot satisfy the conflicting requirements of the two conjuncts.

With this in mind, let us turn to the analysis itself.

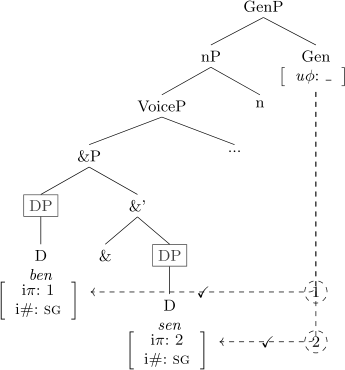

Following a standard analysis of coordinate structures, we take it that coordination is the projection of a & head whose specifier and complement are filled by the first and second conjunct, respectively (e.g., Munn 1993, 1999; Benmamoun et al. 2009; Marušič et al. 2015), as shown in (62). We also assume, with Citko (2018) and Al Khalaf (2021), that neither & nor &P bear ϕ-features, and that no feature percolation is operative in coordination. As such, external probes target the conjuncts themselves via Agree, similar to summative agreement in right node raising (e.g., Grosz 2015), rather than targeting the maximal projection &P that collects the features of the conjuncts.Footnote 29

-

(62)

When a coordination is probed directly by the split probes, T or Poss, the derivation will proceed unproblematically: the person probe will access the person features of each conjunct in turn (when the coordination does not involve a third person nominal), or of just the local person (when we are coordinating a local and a non-local person). The number probe will access the number feature of each conjunct in turn, since both conjuncts will always bear number. Once T/Poss has collected the relevant set of features, the feature resolution algorithm will apply. The important point is that, since the T and Poss probes are split, they will always find a way to be valued successfully when probing a coordination.

Of interest, then, is what happens when the conjunctive Gen probe attempts to Agree with a coordination. Let us start with the first configuration, in which local conjuncts are coordinated, e.g., (1+2), and examine agreement with the Gen probe. The crucial aspect of the derivation is that, since both conjuncts contain the interpretable person feature, the Gen head that bears the conjunctive [uϕ] probes will be inserted. It finds its match when it targets both conjuncts, and the language-specific feature resolution algorithm is computed, resulting in first plural agreement.

-

(63)

Coordination of local + local conjuncts (e.g., ben ile sen ‘I and you’)

Combinations of non-local persons (3+3), e.g., o ile Leyla ‘s/he and Leyla,’ involve conjuncts whose internal structure (and feature set) are different than local persons. Since nonlocal conjuncts are NumPs (which lack the person feature), the Gen head with only the [u#] probe will be inserted. This probe can exhaustively find its interpretable match in each conjunct, as a result of which feature resolution can take place, again yielding resolved agreement.

-

(64)

Coordination of nonlocal + nonlocal conjuncts (e.g., adam ile Leyla ‘the man and Leyla’)

The crucial configurations are those in which a local and a non-local person are conjoined. Recall that in such cases, resolved agreement is disallowed, and default agreement is triggered. Since one of the conjuncts is a DP, the conjunctive [uϕ] probe is inserted (see fn. 24 for the need to license the person feature).Footnote 30 Even though this probe can be valued by the DP conjunct since it exhaustively finds its match, it fails to be valued by the non-local NumP conjunct since that conjunct possesses a subset of the features that are available on the probe. For this reason, feature resolution fails, and default agreement is inserted.Footnote 31

-

(65)

Coordination of local + nonlocal conjuncts (e.g., ben ile Leyla ‘I and Leyla’)

Note that the failure of the feature resolution mechanism just mentioned means that the probe should not be able to just realize the features of one conjunct; in other words, in (65), first singular from the first conjunct plus no value from the second conjunct does not resolve to first singular, but rather results in default agreement. Further patterns of local+nonlocal coordination demonstrate that this is indeed the case, shedding further light on the inner workings of agreement with coordinations and confirming our assumptions thus far.

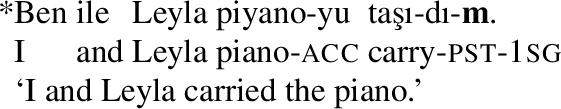

For instance, when the local conjunct of a local+nonlocal coordination is singular, (66), it still cannot trigger plural agreement on the probe, which would be expected if the whole operation was simply summation of the appropriate features from different conjuncts. This observation further supports the idea that the requirements of the probe need to be independently satisfied for each conjunct; only then can feature resolution take place.

-

(66)

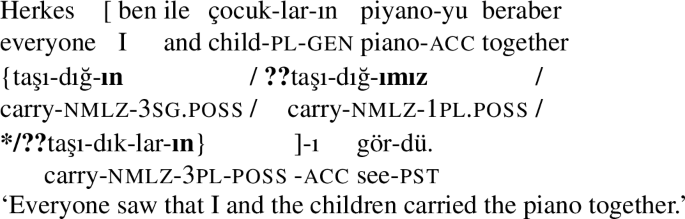

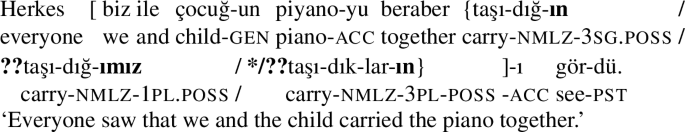

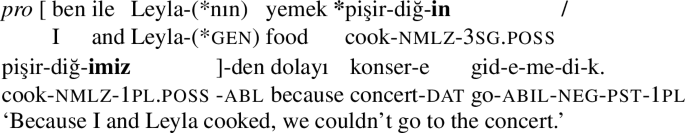

Another example is provided in (67), in which a first plural pronoun is conjoined with a singular common noun. In this example as well, default agreement is triggered. Realizing the features of only one of the conjuncts, which would yield the first plural form taşı-dığ-ımızFootnote 32 or the third plural taşı-dık-lar-ın, is not possible.

-

(67)

2.4 Interim conclusion

In this section, we have introduced the Turkish DTNs and examined their internal structure. We have noted that the emergence of default agreement when these complex pronominals are marked genitive is the result of the interaction of two factors, namely, the way in which person and number features are contributed structurally, and the feature specifications of T and Poss on one hand, and of Gen on the other.

The ingredients we adopt ensure that the system can correctly capture the intricate behavior of the so-called DTNs as opposed to pronouns, as well as leave enough room to understand the inner workings of individual DTNs. The first main component of the analysis just developed concerns how interpretable ϕ features are distributed in pronouns vs larger nominals: whereas interpretable ϕ features are bundled on a single head in simplex pronouns, they are distributed throughout the larger structure in DTNs. Given the presence of Poss as well as Gen in the nominal domain as probes, with the former being the nominal counterpart of T, the second main component relates to the structure of probes: on the T and Poss heads, person and number features probe separately, whereas on the Gen head, the two features form a conjunctive probe. The resulting system guarantees that all probes will be successfully valued by simplex pronouns, yielding co-varying agreement in this case; but the different featural make-up of DTNs leads to a different situation when these interact with the different probes. T and Poss trigger co-varying agreement when they probe DTNs directly; but Poss ends up realizing default agreement when it embeds a Gen head that probes a DTN.

A further subdivision is drawn within Gen itself, which can either host a conjunctive probe (with person and number probing together) or a probe with just the uninterpretable number feature. This divide allows us to capture the complex behavior of coordinate phrases, while maintaining the essence of the overall analysis.

Though the eventual system has a few moving parts, we believe it ultimately offers a parsimonious and, importantly, unified account of an extremely complex set of facts, thereby paving the way for our analysis of the interaction of binding with agreement in Sect. 3.Footnote 33

2.5 Brief excursus: Partitives

In the next section, we discuss the connection between binding and agreement. However, before proceeding with that discussion, we briefly note the distinct behavior of “partitives,” which are usually treated on par with other DTNs (see e.g., Ince 2008; Paparounas and Akkuş 2020; Satık 2020). However, a closer investigation reveals that “partitives” exhibit properties that warrant identifying them as a distinct type from the genuine DTNs (multi-plural pronouns, adnominal pronouns and coordinations of local+nonlocal persons).

The crucial observation is that, unlike genuine DTNs, partitives do not exhibit a contrast between verbal and nominalized clauses. In (root or embedded) verbal clauses, partitives trigger co-varying agreement, like DTNs; but, unlike in the case of DTNs, this is not the only option. Default agreement is also allowed (although not as readily). This possibility is shown in (68).

-

(68)

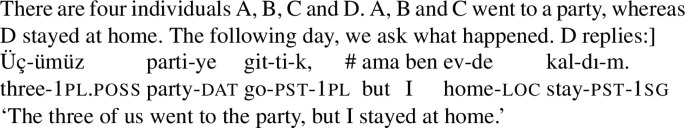

In this connection, we have made what we believe is a novel observation for Turkish, namely, that the presence or absence of the co-varying agreement corresponds to a clusivity effect (more precisely, it tracks the inclusion of the speaker). In the normal case, an agreeing partitive is interpreted as definite. To see this, consider the following disambiguating context:

-

(69)

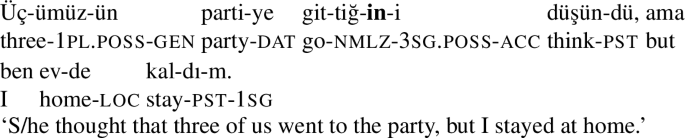

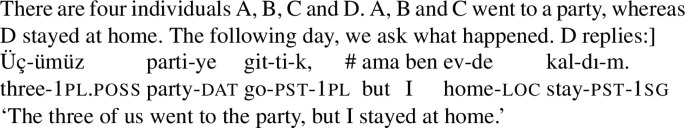

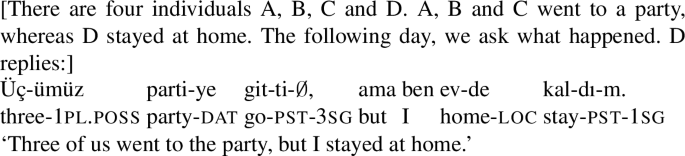

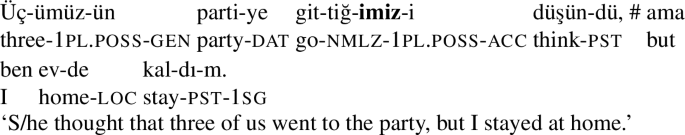

(69) is infelicitous in the context given, just like the English translation. This suggests that the agreeing partitive üçümüz is interpreted as speaker-inclusive: it must mean ‘a set of three that includes the speaker,’ as opposed to the weaker interpretation corresponding to English three of us.

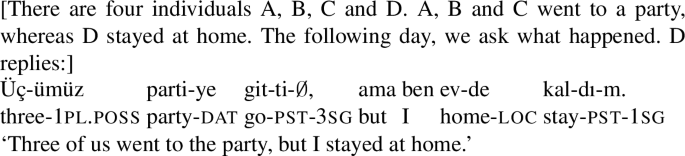

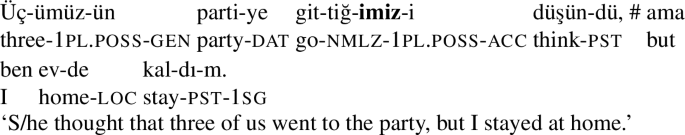

Intriguingly, however, this is not the only interpretive possibility. Partitives have the additional option of not agreeing with the finite verb, unlike DTNs. Non-agreement has an effect on interpretation; contrast (69) with the following example:

-

(70)

In (70), the partitive does not agree with the verb; strikingly, the continuation but I stayed at home is now felicitous. In other words, agreeing partitives are interpreted as definite and inclusive, whereas non-agreeing partitives correspond to English three of us, which may or may not include the speaker.Footnote 34

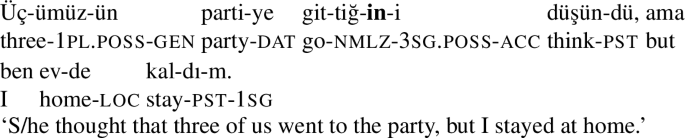

Crucially, clusivity also plays a role in agreement in nominalized clauses. Even though default agreement is the most readily available option, it turns out that once clusivity is taken into consideration, co-varying agreement is also acceptable, and thus parallels the facts in root clauses.Footnote 35 Consider (71) and (72).

-

(71)

-

(72)

As such, partitives behave differently from the DTNs, which is observable once the clusivity factor is taken into consideration. Noting this interesting property of partitives whose investigation is being undertaken separately, we move on to the discussion of the second generalization, which examines the connection between binding and agreement.

3 Generalization 2: Binding enables agreement

3.1 Data

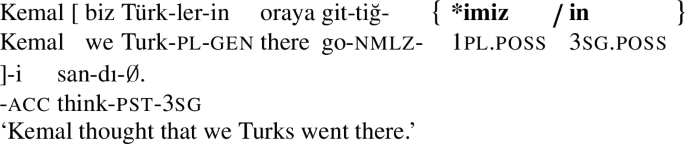

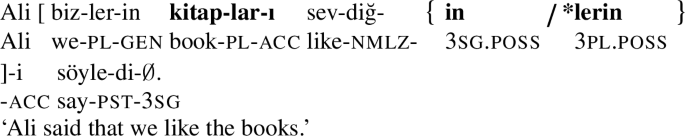

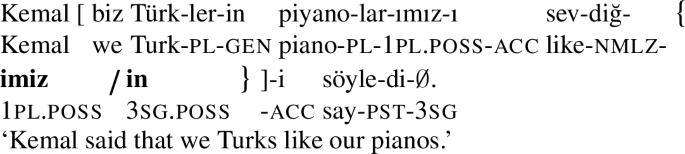

As illustrated in the previous section, DTNs in nominalized clauses cannot participate in co-varying agreement. Example (18), repeated here as (73), established this fact for the DTN subject of an intransitive verb like git- ‘go’; but nothing changes if the DTN is the subject of a transitive predicate whose internal argument is a common noun (74):Footnote 36

-

(73)

-

(74)

In (74), the genitive-marked DTN fails to agree with the nominalized verb sev- ‘like,’ whose object is the common noun kitap ‘book.’ Given the data seen so far, this is expected.

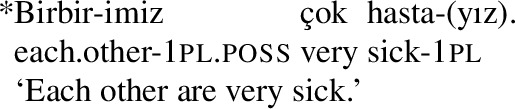

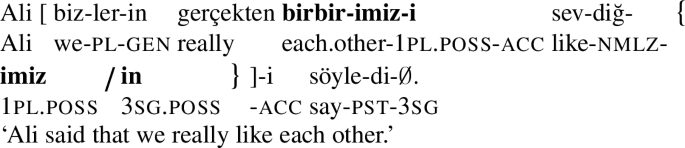

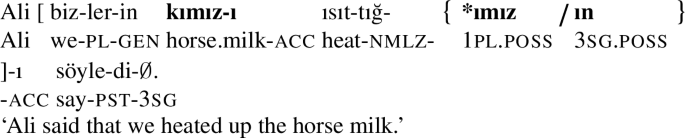

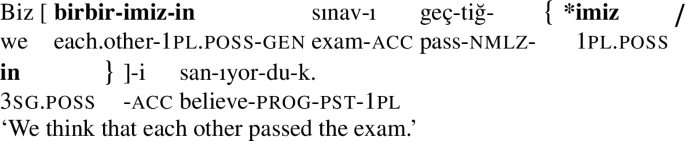

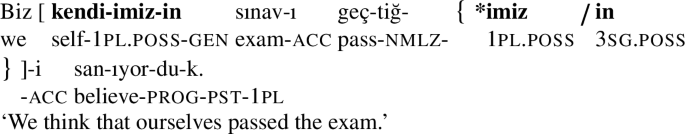

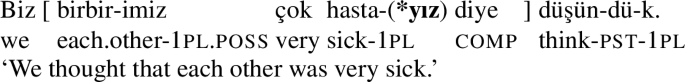

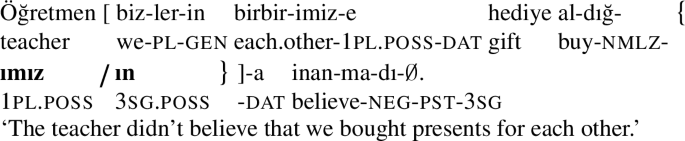

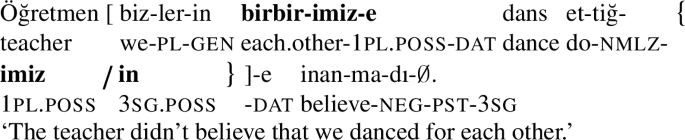

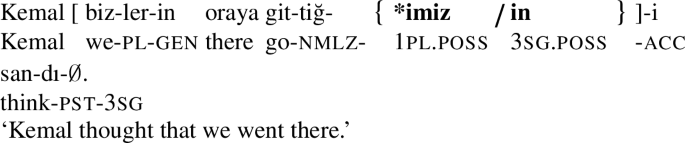

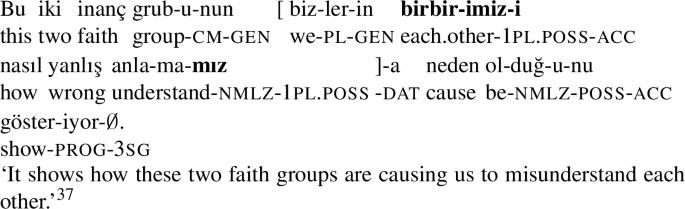

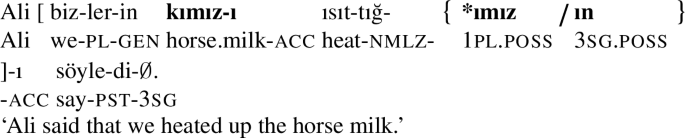

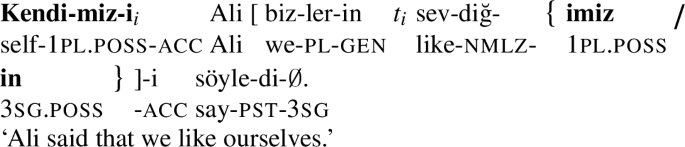

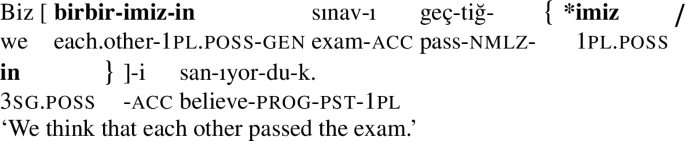

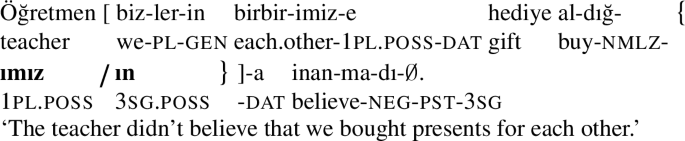

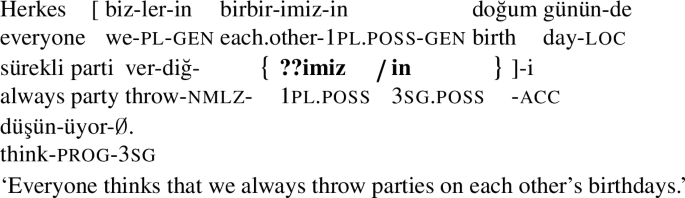

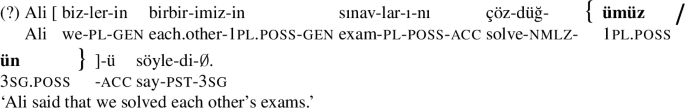

Strikingly, a genitive-marked DTN can participate in nominal agreement when it binds an object reciprocal:Footnote 37

-

(75)

-

(76)

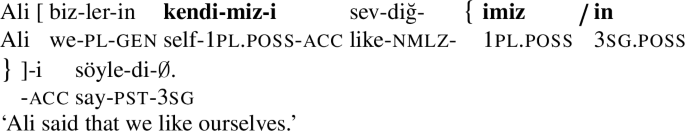

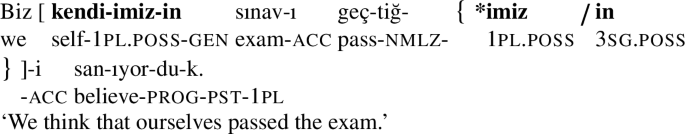

The same pattern obtains when the multi-plural pronoun binds an object reflexiveFootnote 38 (77) or a bound pronounFootnote 39 (78): whenever a genitive-marked DTN subject binds one of these elements, it can agree.Footnote 40

-

(77)

-

(78)

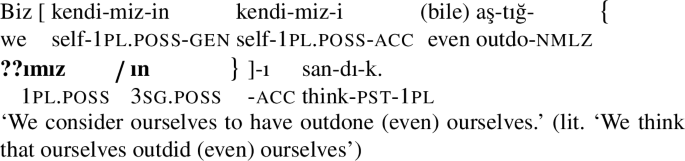

(79) is another attested example (also confirmed by our consultants) that illustrates both agreement possibilities under binding. It is a student-club announcement, which has two versions, one with full agreement, and the other with default agreement.Footnote 41

-

(79)

In summary, in (75)–(79), which only differ from (74) in that the embedded object is anaphoric (and from (73), which lacks an object), co-varying nominal agreement seems to be made possible through binding.

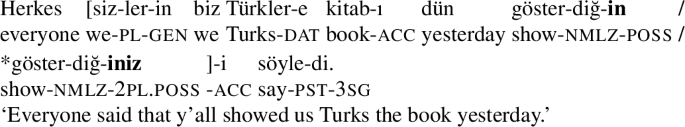

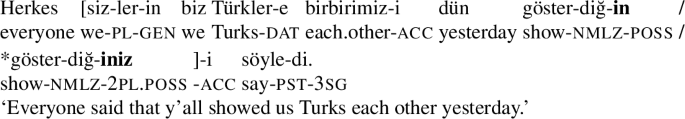

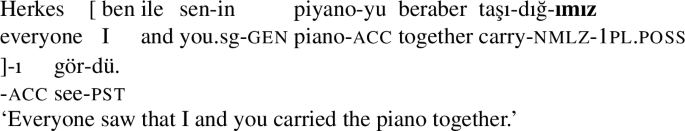

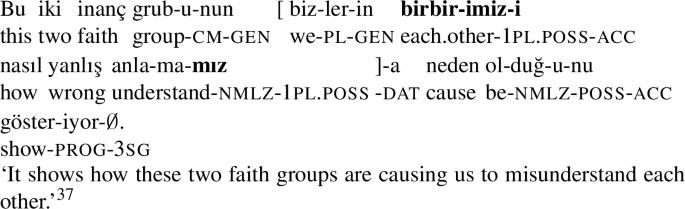

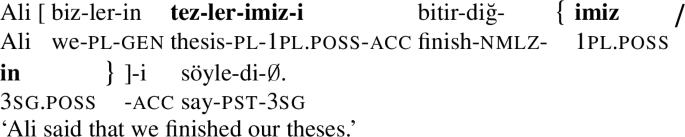

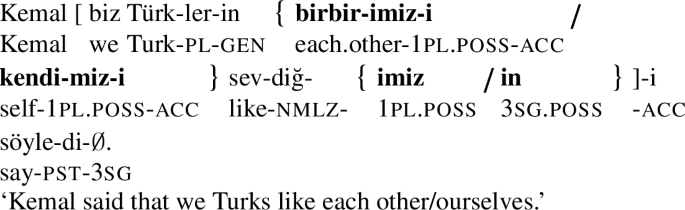

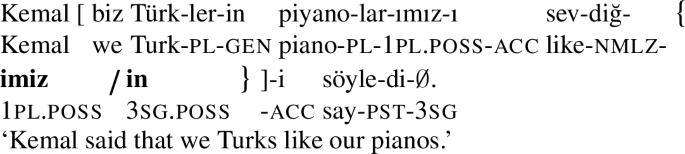

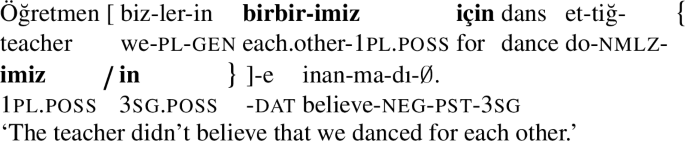

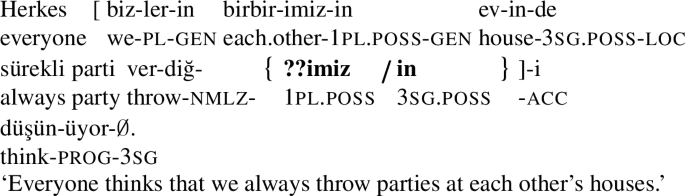

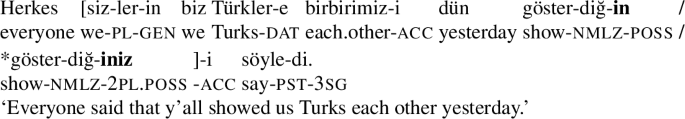

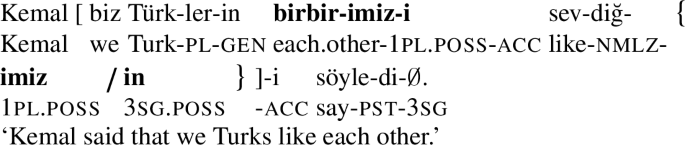

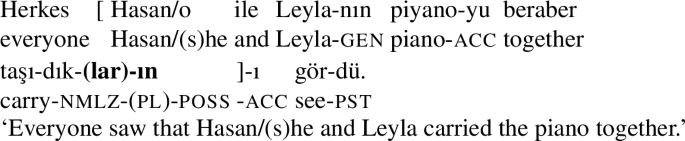

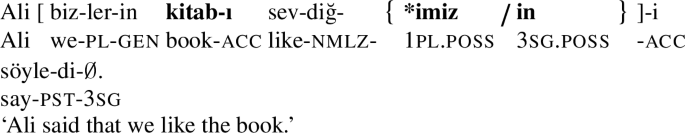

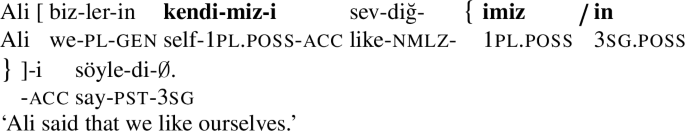

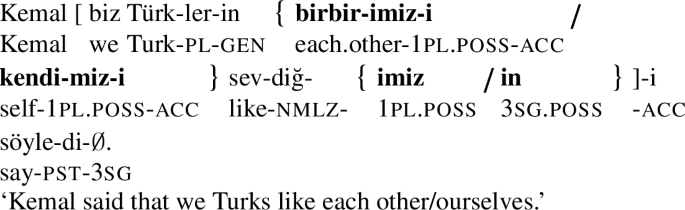

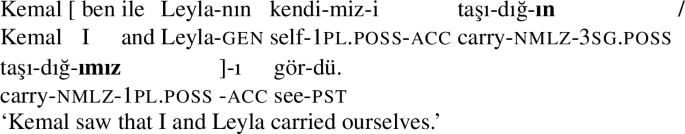

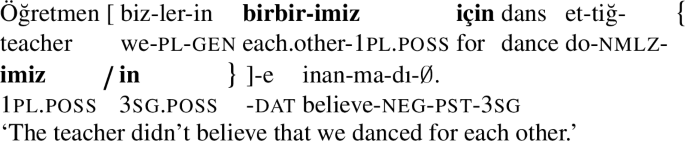

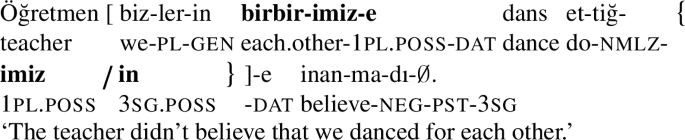

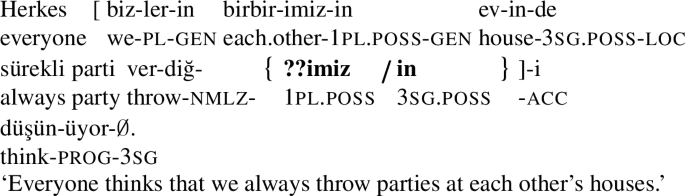

The examples so far show that a genitive-marked multi-plural pronoun triggers co-varying agreement when it binds. The other DTNs obey the same pattern. (80)–(82) illustrate the same generalization for adnominal pronouns.

-

(80)

-

(81)

-

(82)

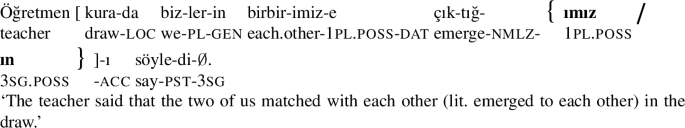

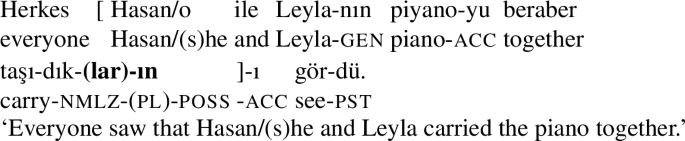

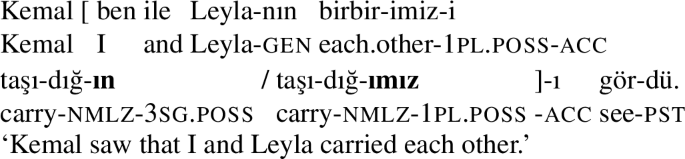

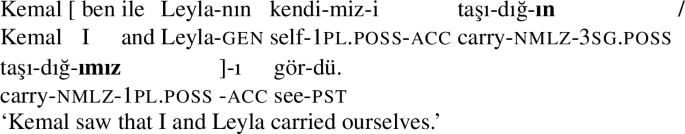

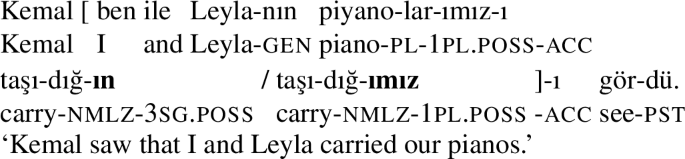

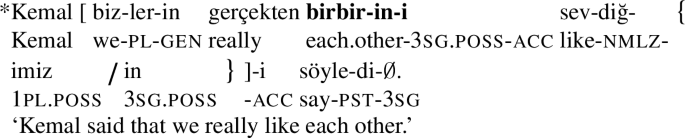

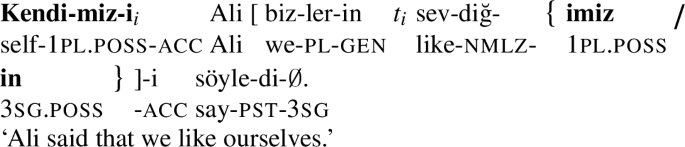

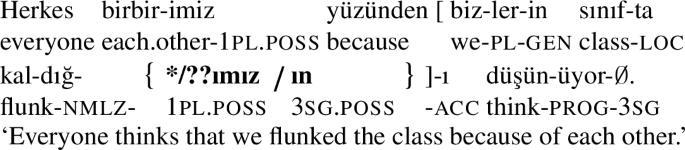

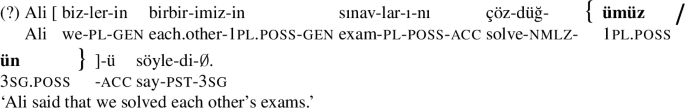

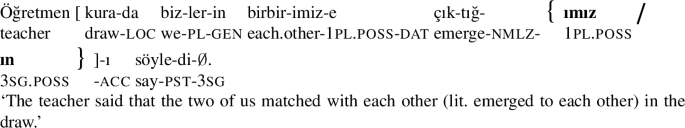

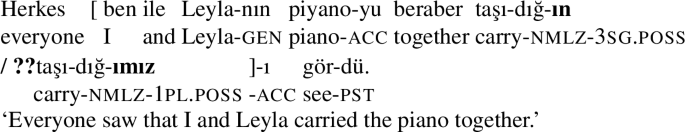

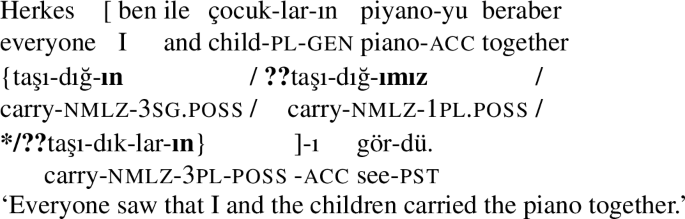

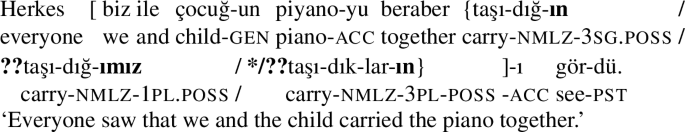

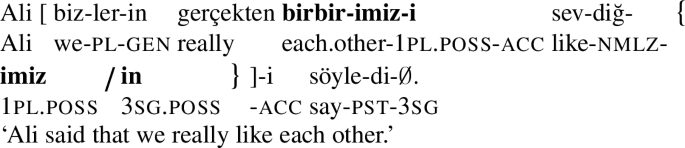

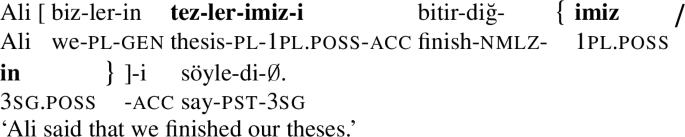

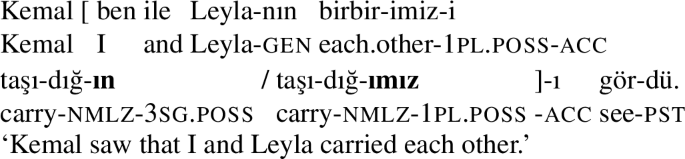

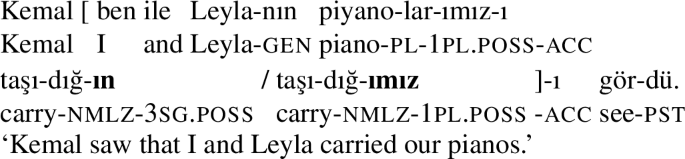

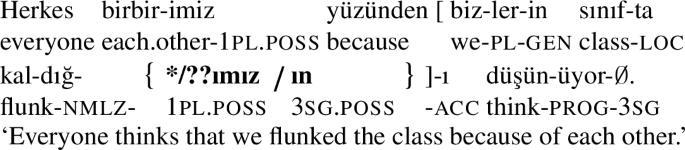

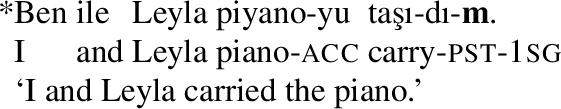

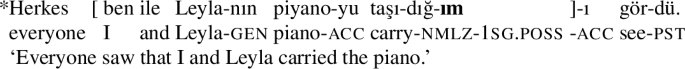

Coordinate pronouns also behave the same. Recall that coordinations of local and non-local persons are part of the DTN category in that while otherwise they trigger co-varying agreement, they result in default agreement in nominal contexts (cf. Sect. 2.3.5). For Grammar 3 speakers, these coordinate phrases also participate in the binding/agreement interaction: when genitive, they can only control agreement if they bind. This fact is illustrated in (83) for reciprocals, in (84) for reflexives, and in (85) for bound pronouns.

-

(83)

-

(84)

-

(85)

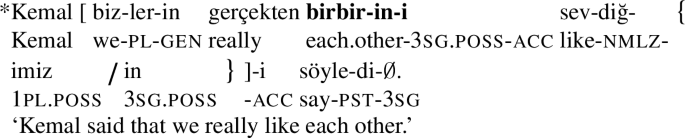

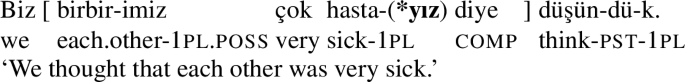

Importantly, regardless of the agreement indexed on the nominalized verb, the anaphor itself must inflect for the ϕ-features of its antecedent:Footnote 42

-

(86)

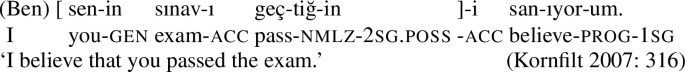

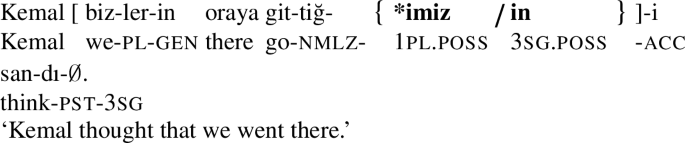

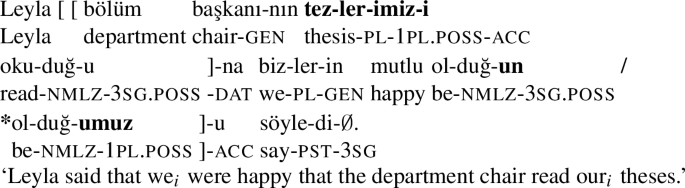

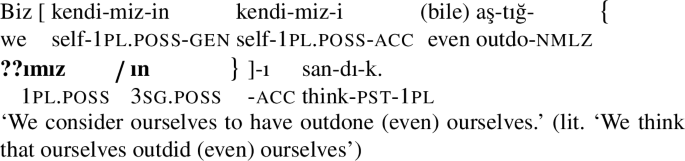

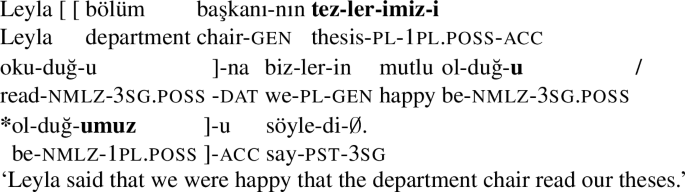

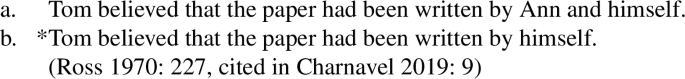

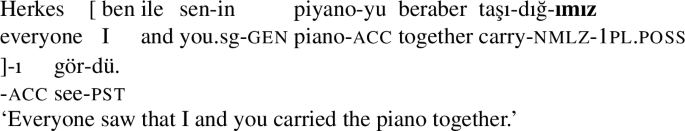

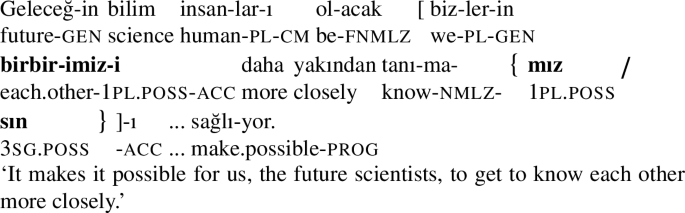

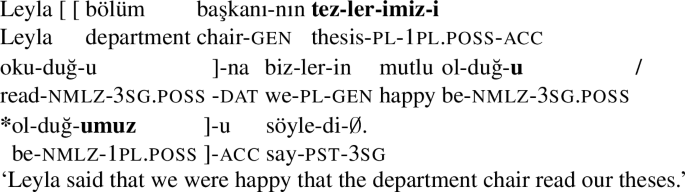

Crucially, the striking interaction between binding and agreement just discussed is local. This fact is best illustrated with bound pronouns, which, unlike local anaphors, need not have a local antecedent. In (86), the bound pronoun is in the lowest embedded clause, introduced by read, while its DTN antecedent is the subject of the higher verb be happy. In this situation, where a clause boundary intervenes between the DTN binder and its bindee, the DTN does not trigger co-varying agreement on the first embedded verb.

-

(87)

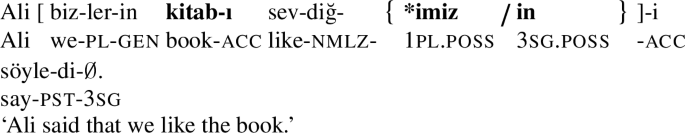

A possibility to examine is whether the contrast can be explained in surface-oriented (perhaps processing-related) terms, for example, by assuming that the presence of full agreement on the verb is facilitated by the presence of the phonology of full agreement on the bound reflexive.Footnote 43 Having a common noun whose phonology resembles that of full agreement as in (88), allows us to show that it cannot solely be a processing issue (thanks to Yılmaz Köylü for providing the example).

-

(88)

Note also that the emergence of co-varying agreement cannot be attributed to linear order either: the phenomenon persists if the bound element is scrambled out of the nominalized clause.

-

(89)

There is thus exactly one situation where a genitive-marked DTN can participate in nominal agreement, namely, when it acts as a local binder. The generalization is then as follows:

-

(90)

Generalization 2: Binding enables agreement

A

-marked DTN can only agree if it locally binds an anaphor or bound pronoun.

-marked DTN can only agree if it locally binds an anaphor or bound pronoun.

(90) suggests an intimate connection between local binding and ϕ-agreement. The observed pattern—that local binding licenses an otherwise impossible agreement possibility—furnishes an intuition that Agree-based accounts of binding should be perfectly poised to capture. If binding involves transmission of ϕ-features, then binding configurations provide an extra set of features that can be targeted for agreement.Footnote 44 Sect. 3.2 develops an analysis aiming to capture just this intuition. Section 4 then offers refinements to the empirical picture presented here, and sketches their consequences for the generality of an Agree-based approach to binding.

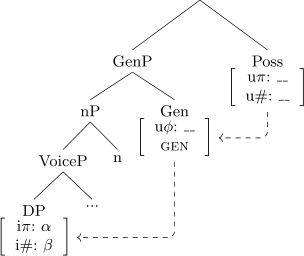

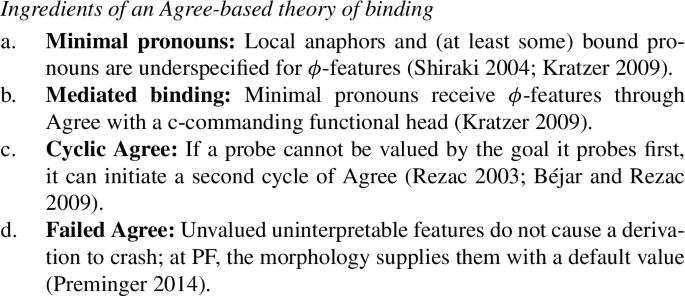

3.2 Analysis

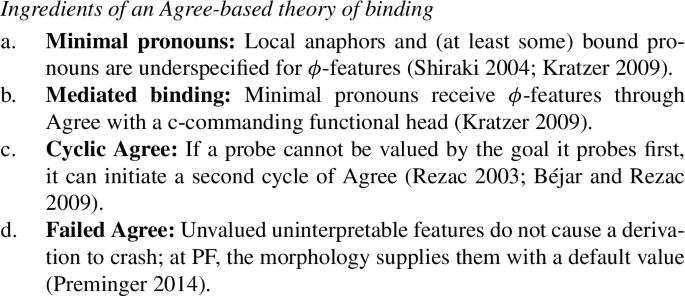

Our account of the binding/agreement interaction will make use of the following pieces of theoretical technology, the last two of which we have already introduced.

-

(91)

The view of the mechanics of Agree-based binding defined by (91a)–(91d) is one of many possible ones. In fact, the only ingredient typically shared across Agree-based theories of binding is (91a); different theories flank this basic ingredient with different assumptions. For example, Reuland (2011) proposes that a single functional head Agrees both with the minimal pronoun and its antecedent, in contrast to (91c). As for (91b), one theory departing from this assumption is found in Wurmbrand (2017), where binding is implemented as an unmediated DP-DP dependency via Reverse Agree. At the end of this section, we will clarify which of the ingredients in (91) are crucial in accounting for (90), and which are assumed for the sake of concreteness. The Turkish facts speak clearly in favor of the role played by ϕ-Agree in local binding, albeit without necessarily distinguishing between different ϕ-Agree-based theories.

(91a) amounts to the claim that a nominal bearing interpretable ϕ-features need not have these features inherently valued. Kratzer (2009) argues that the syntactic representation of some referentially deficient elements—namely anaphors and (some) bound pronouns—should be understood along these lines. For Kratzer, the structural deficiency of minimal pronouns translates into a semantic deficiency: ϕ-deficient elements are variables bound by the closest binder. Under the theory in Kratzer (2009), this is where (91b) becomes crucial: binders are hosted on functional heads. Kratzer goes on to develop a theory that effectively assimilates the relationship between a variable and a binder to that between a goal and a c-commanding probe, whereby the goal is an argument (cf. Pollard and Sag 1992; Reinhart and Reuland 1993) and the probe is a functional head that licenses and Agrees with that argument. Broadly speaking, the mechanism that serves to transmit ϕ-features from the probe to the goal in the syntax supplies the conditions for variable binding in the semantics.

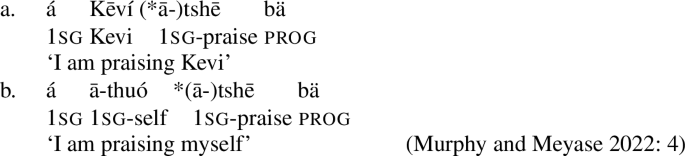

As Kratzer points out, two preliminary morphological facts about anaphors suggest that ϕ-features must be somehow implicated in binding. Firstly, anaphors often match the ϕ-features of their antecedents:Footnote 45

-

(92)

Mary likes {her / *my / *your}-self.

Secondly, anaphors often fail to control co-varying agreement, as suggested by the observations subsumed under the Anaphor Agreement Effect (Rizzi 1990; Woolford 1999; Tucker 2011; Murugesan 2019). The AAE is naturally predicted given underspecification. If anaphors inherently lack ϕ-features, they should be unable to value agreement probes, yielding either ungrammaticality or a default/“special” form of agreement—both outcomes are indeed attested cross-linguistically (Tucker 2011; Sundaresan 2015). In fact, the view of anaphors as minimal pronouns makes a more specific prediction with respect to the AAE. The AAE should arise whenever a probe attempts to Agree with an anaphor that has not yet received ϕ-features from its antecedent. But if Agree targets an anaphor that has already been bound through ϕ-feature transmission, agreement with the anaphor should be successful, leading to an apparent violation of the AAE. Murugesan (2019, 2022) argues that the latter scenario is indeed the case in AAE-violating configurations.

There is thus some morphological evidence in favor of the underspecification of anaphors, and thus of the relevance of ϕ-features to binding. The Turkish binding/agreement interaction offers one more piece of evidence of this kind, one that is novel and striking; as we will now show, this interaction finds a natural analysis in terms of (91a), in conjunction with the other ingredients in (91). Recall that (91c) and (91d) were already introduced in the analysis of Relativized Case Opacity above.

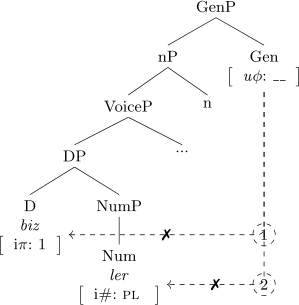

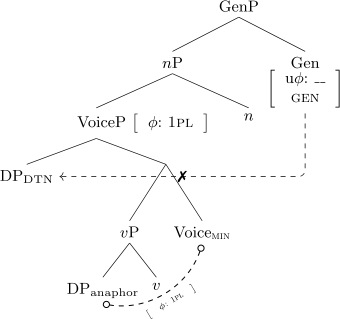

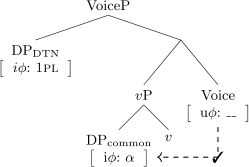

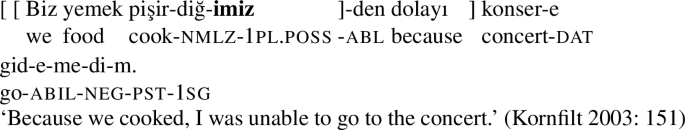

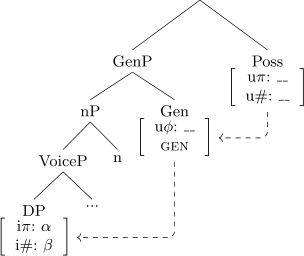

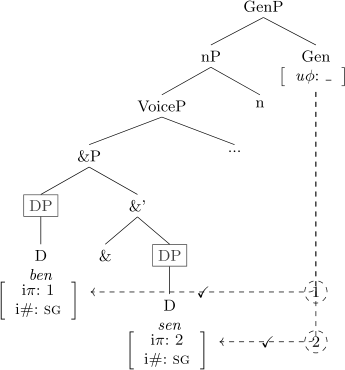

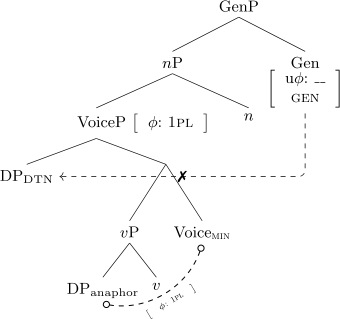

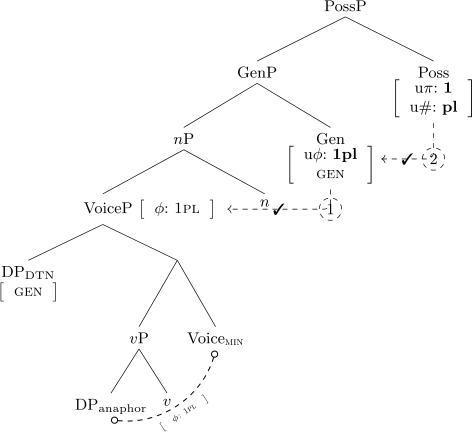

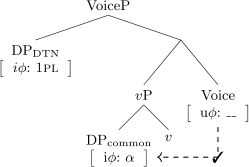

To see how (91) can derive the fact that the opacity is overridden when a DTN binds, consider the bottom-up derivation of a nominalized embedded clause with an object anaphor. Recall from Sect. 2.1 that these clauses involve a full verbal shell. We take this to consist of a vP introducing the root (not shown here) and the internal argument, and a separate projection VoiceP hosting the external argument (Kratzer 1996, Pylkkännen 2008, Legate 2014i.a.). In this case, the internal argument is a ϕ-underspecified anaphor, and the external argument a first-plural DTN. For reasons to be clarified later (see Sect. 3.4), we take a special flavor of Voice to be present in the structure, namely Voicemin(imal), inspired by the Voicereflexive of Ahn (2015) (cf. Labelle 2008; Kratzer 2009). This head is tasked with licensing minimal pronouns via Agree (and possibly concomitant case assignment, which is irrelevant here)—in (93), Voice attempts to do just this, reflecting (91b).

-

(93)

-

(94)

Because the anaphor has no ϕ-features to transmit to the probe, this Agree operation cannot result in valuation. In (94), following Murphy and Meyase (2022), we take this state of affairs to lead to feature-sharing between Voice and the anaphor (Frampton and Gutmann 2000; Pesetsky and Torrego 2007). This feature cannot be valued by downwards Agree, since the probe’s c-command domain contains no further goals. We follow Béjar and Rezac (2009) in assuming that, in just this situation, the probe can search for a goal in its specifier. The specifier of VoiceP is filled by the DTN subject; crucially, the ϕ-features on this nominal are accessible at this point.Footnote 46

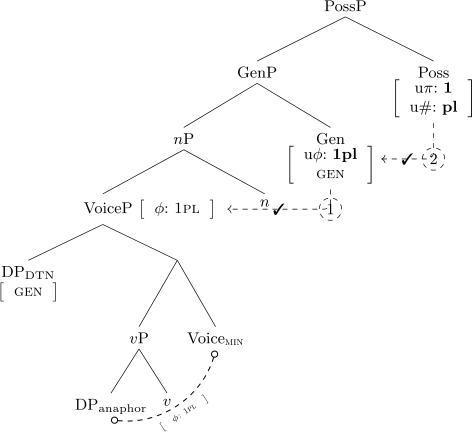

In (95) below, the features of the DTN have valued the feature shared between Voice and the minimal pronoun, and percolated to the maximal projection VoiceP. At this point, the higher verbal projections making up the nominalized clause will be merged; since these play no role in the analysis, we have omitted them in the trees. The nominal superstructure of the nominalized clause will be merged next; we take this to consist first of a categorizing head n, where the nominalizing suffixes of Turkish are realized, and Gen, the assigner of genitive Case.Footnote 47

Recall now that, once it has assigned genitive Case, Gen will initiate a first cycle of Agree through its conjunctive probe. We take it that this first cycle of Agree by Gen targets the nominal that Gen has just assigned Case to (similar to instances of possessor agreement, see e.g. Deal 2010 and cf. footnote 58). In the structure we have been building, this nominal is a DTN; thus, by the mechanism described in detail in Sect. 2.3, Agree will fail (95), since the DTN’s distributed ϕ features cannot value Gen’s conjunctive probe. From this point onward, the derivation can proceed in two different ways.

-

(95)

If nothing else happens, once the nominal probe Poss is merged, it will fail to find features on Gen; with the structure below Gen having been spelled out, Poss will not find another suitable goal and will itself remain unvalued, yielding default third-singular values at PF. This situation is schematized in (96) (where we do not illustrate the split probe on Poss as two separate branches, compare (50), simply for space reasons).

-

(96)

Outcome 1: Gen remains unvalued, and Poss too

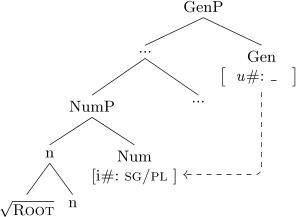

But there is a second possibility: once Gen fails to be valued by the nominal it has assigned Case to, it may initiate a second cycle of Agree, probing the structure again. Crucially, the rest of the structure does provide a second suitable goal, namely, VoiceP, where the features left after by binding reside. Crucially, the ϕ features on Voice are bundled together (unlike on the DTN), and are thus capable of valuing the conjunctive probe on Gen. With Gen valued, Poss can inherit said values from Gen, yielding co-varying nominal agreement.

-

(97)

Outcome 2: Gen is valued by VoiceP’s features

On the whole, then, the effect of binding on the agreement possibilities of nominalized clauses with a DTN subject can be understood as follows. (96) represents the normal case, where a DTN fails to value Gen, resulting in the insertion of default features at PF. But because binding involves transmission of ϕ-features, the relevant structures, where the DTN is a binder, also furnish an additional set of ϕ features on the maximal projection of the mediating head Voice; the second round of Agree initiated by Gen finds these features, resulting in covarying agreement. Because this second cycle of Agree is optional, some derivations will involve just the first cycle of Agree; we thus correctly predict to find optionality between  and

and  nominal agreement under binding, explaining the full pattern.Footnote 48

nominal agreement under binding, explaining the full pattern.Footnote 48

This analysis has a number of merits. It successfully captures the crucial aspects of the Turkish data outlined in Sect. 3.1. Since the second cycle of Agree, whereby Gen finds the “binding features” on Voice, is optional, co-varying agreement may, but need not, surface when a DTN binds an anaphor locally. Crucially, however, the binding features are present on the feature shared by VoiceP and the anaphor regardless of whether Poss accesses them or not. As such, irrespective of whether the nominal part of the structure manages to reflect full agreement or not, the anaphor will always be bound, and will invariably match the ϕ-features of its antecedent. Under this analysis, the same features will be present on Voice when the subject is a simple pronoun, as opposed to a DTN. But in this case, Gen will never have reason to find them: it will be able to Agree with the pronoun directly, genitive-marked pronouns not being opaque for agreement. As such, the first cycle of probing will always be successful when the subject is a simple pronoun, and the second cycle (the one capable of targeting Voice) will not be initiated.