Abstract

This article provides a solution to the long-standing puzzle of English anaphors within so-called picture noun phrases, which superficially exhibit an exceptional binding behavior. In particular, picture noun anaphors seem, under certain conditions, to escape the locality conditions imposed by Condition A of Binding Theory. Previous proposals attribute such apparently exceptional behavior to various sources: the classical Binding Theory appeals to the possible presence of covert agents within NPs; predicate-based theories introduce the possibility of exemption from Condition A; others capitalize on possible homophony with (logophoric) pronouns. While all of these proposals provide valuable insight into some aspect of the puzzle, we show that they all fail to capture the full empirical picture. Based on a detailed examination of their behavior in various syntactic and interpretive conditions, we instead propose that English picture noun anaphors, like any other anaphor, systematically obey Condition A. Their apparent exemption from it in some cases derives from the possible implicitness of some binders, in particular, logophoric pronouns or nominal subjects. Furthermore, the availability of such covert binders is crucially affected by a binding-independent competition principle between weaker and stronger forms. Thus, the apparently irregular behavior of English picture noun anaphors results from the interaction between several factors (syntactic representation of logophoricity, syntactic projection of subjects in nouns, pronominal competition), which is responsible for the illusion that Condition A does not apply systematically. By disentangling these factors, we propose a solution that integrates previous insights without compromising on empirical adequacy or analytical parsimony.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Since Warshawsky (1965) coined the term picture nouns to refer to phrases headed by representational nouns like picture or story, the behavior of English anaphors within such phrases has remained an outstanding issue for theories of binding. In particular, reflexives and reciprocals in picture noun phrases (henceforth, Picture Noun Anaphors or PNAs) seem to routinely disobey the locality conditions imposed by Condition A of Binding Theory, as illustrated in (1)–(2).

-

(1)

Tomi believes that there is a picture of himselfi hanging in the post office. (Jackendoff 1972: 133)

-

(2)

[The men]i knew that there were pictures of [each other]i on sale. (Pollard and Sag 1992: 267)

This type of observation led many (starting with Postal 1971Footnote 1—see also Bouchard 1984; Rooryck and Vanden Wyngaerd 2011; among many others) to assume that PNAs form an exceptional class of anaphors. Drummond, Kush and Hornstein’s assumption is representative in this respect: “a reflexive within a picture noun phrase that is bound from outside its containing noun phrase is not a true reflexive subject to principle A. Rather, it is a pronominal with special logophoric requirements. This follows a long tradition of analysis [...]” (Drummond et al. 2011: 401).

A closer look at the literature reveals that the two main theories of anaphor licensing do not, however, assign a specific status to PNAs. First, Chomsky (1981, 1986) supposes that just like any anaphor, PNAs obey Condition A of Binding Theory, and must thus be bound within the smallest phrase containing them and a subject distinct from them.Footnote 2 Chomsky further posits the possible presence of a PRO-like implicit subject within DPs to account for the fact that anaphors like each other in (3) (vs. (4)) are not in complementary distribution with pronouns as expected under the classical Binding Theory (see further discussion in Sect. 2.1.1.3); the contrast between (3) and (4) derives from the meaning difference between tell and hear.

-

(3)

-

a.

Theyi heard stories about [each other]i.

-

b.

Theyi heard [PROk stories about themi]. (Chomsky 1986: 166–167)

-

a.

-

(4)

-

a.

Theyi told [(PROi) stories about [each other]i].

-

b.

* Theyi told [PROi stories about themi]. (Chomsky 1986: 166–167)

-

a.

Second, predicate-based theories (henceforth PBTs—see Pollard and Sag 1992; Reinhart and Reuland 1993; and subsequent versions thereof) do not treat PNAs as a special class either. Unlike Chomsky, they argue that PNAs in possessorless DPs are exempt from Condition A, which they redefine as obligatory coargument binding (see further discussion in Sect. 2.1.1.2). But in this respect, PNAs are no different from all other instances of anaphors lacking a coargument, such as (5a) (vs. (5b)). Exempt PNAs also pattern with other exempt anaphors in being subject to perspective-related discourse conditions: himself in (5a), for example, is licensed by the fact that the clause containing it represents the point of view of the referent of its antecedent, Max.

-

(5)

-

a.

Maxi boasted that the queen invited Lucie and himselfi for a drink.

-

b.

* Maxi boasted that the queen invited himselfi for a drink. (Reinhart and Reuland 1993: 670)

-

a.

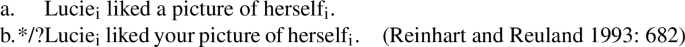

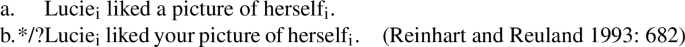

On the other hand, PNAs in possessed DPs are assumed to be subject to Condition A (at least under early PBT versions treating possessors as subjects; see further discussion in Sect. 2.1.2.1); in cases like (6b), the PNA must therefore be bound by the possessor. According to PBTs, this explains the reported contrast between (6a) and (6b).

-

(6)

Thus, PNAs are consistently treated as plain anaphors (in Charnavel and Sportiche’s 2016 terminology) under the Chomskian theory, while under PBTs, PNAs divide into plain anaphors in possessed DPs and exempt anaphors (in Pollard and Sag’s 1992 terminology) in possessorless DPs. In both cases though, their occurrence within phrases headed by the descriptive class of picture nouns does not translate into a specific behavior.Footnote 3

The nevertheless persistent idea of PNA exceptionalism may come from the failure of both theories to capture the full behavior of PNAs. As we will see, Chomsky’s theory is indeed unable to predict the contrast between PNAs under different perspectival conditions. For example, his PRO-based hypothesis should presumably imply that himself will have the same status in (7) and in (1) as long as the author of the picture is the same in both sentences (see further discussion in Sect. 3.2.3): in both, himself should only be acceptable if John took the picture, whether or not his point of view is represented in the clause, contrary to fact.

-

(7)

*Mary said about Johni that there was a picture of himselfi in the post office. (Kuno 1987: 126)

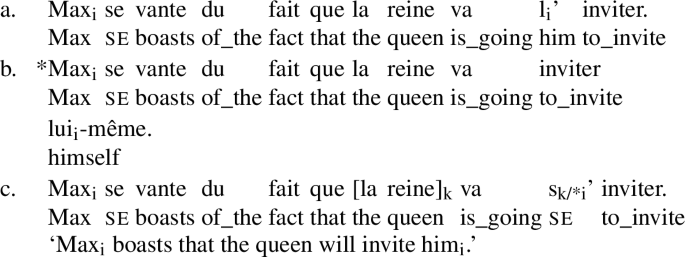

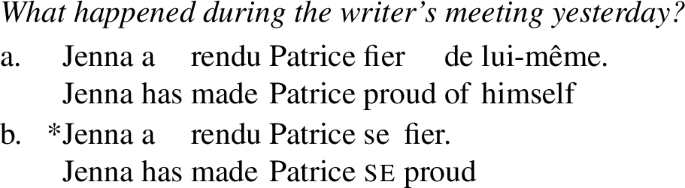

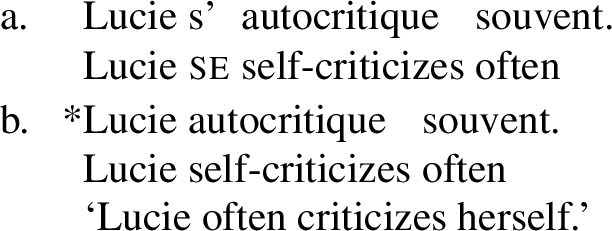

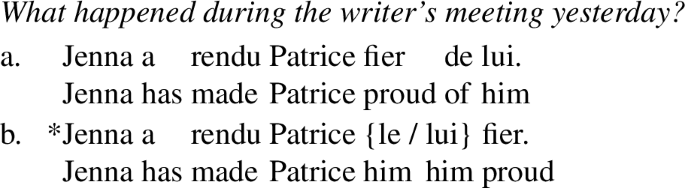

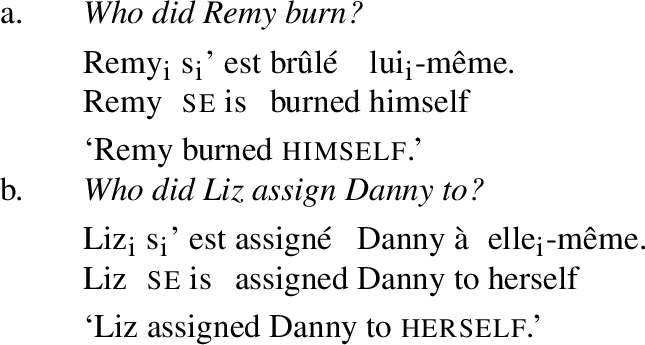

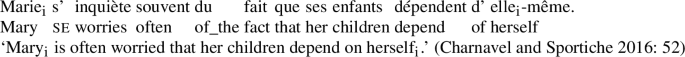

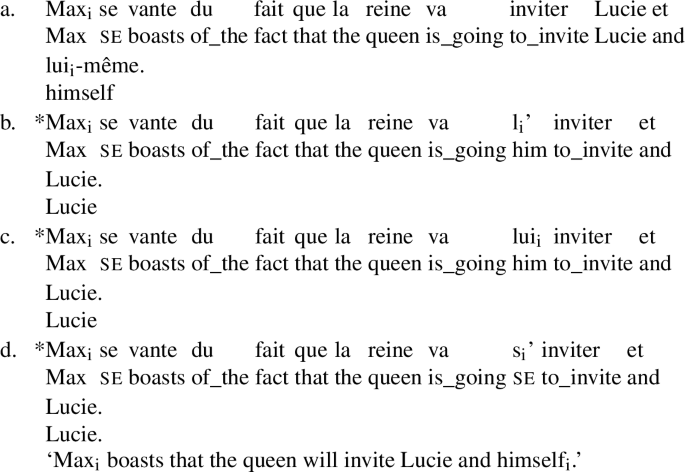

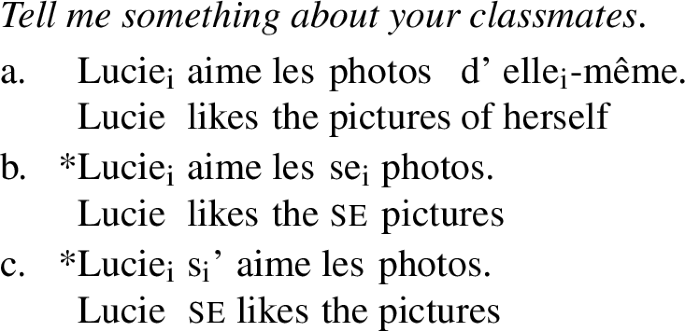

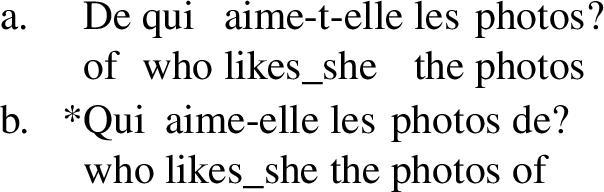

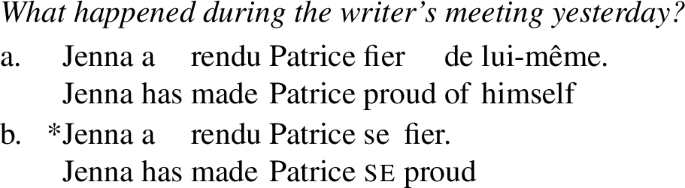

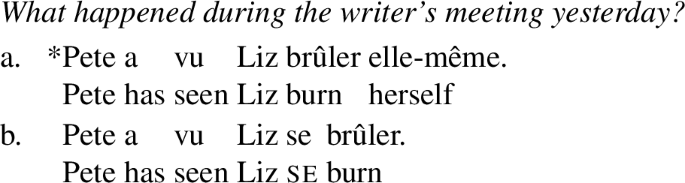

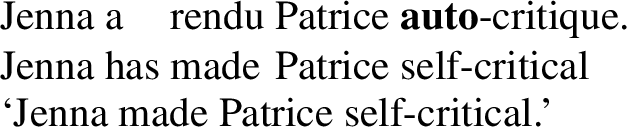

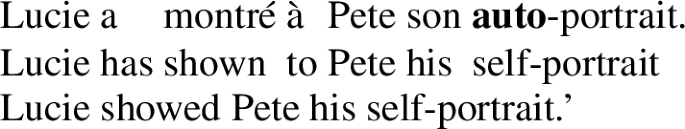

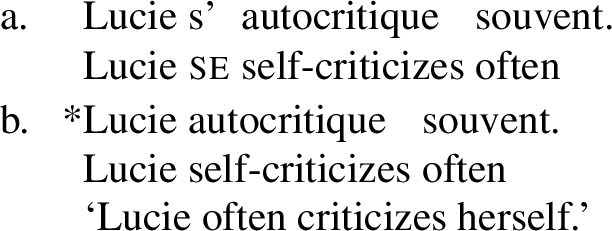

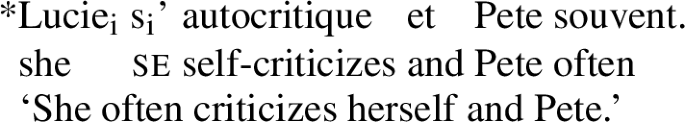

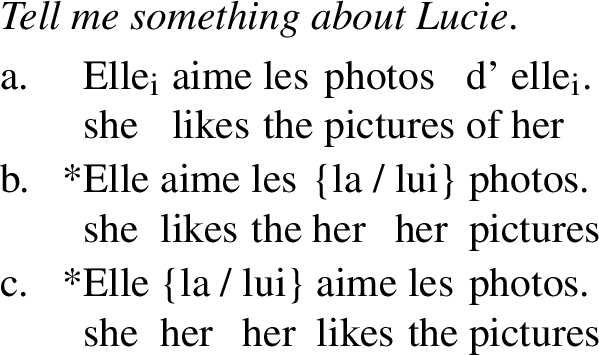

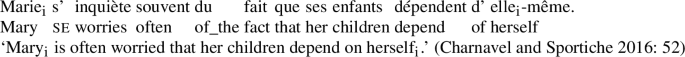

Such sensitivity of PNAs to point of view (argued by Kuno 1972, 1987; Cantrall 1974; Keenan 1988; Zribi-Hertz 1989; i.a.) is what motivated PBTs to develop a theory of exemption, under which himself in (1) and (7) is not subject to Condition A, but to perspective-based discourse conditions.Footnote 4 But conversely, PBTs thereby fail to predict the different grammaticality status of PNAs under different syntactic conditions, as shown for French by Charnavel and Sportiche (2016): in particular, the inanimate elle-même in (8), which lacks a coargument, should under PBTs be excluded in both (8a) and (8b) regardless of the position of its antecedent, given that inanimates cannot take perspective and, hence, cannot satisfy discourse conditions on exemption.

-

(8)

-

a.

[Cette loi]i a entraîné la publication d’un livre sur ellei-même et sur son auteur.

‘[This law]i led to the publication of a book about itselfi and about its author.’

-

b.

[Cette loi]i est si importante que les journalistes prédisent la publication d’un livre sur ellei-même et sur son auteur.

‘[This law]i is so important that the journalists predict the publication of a book about itselfi and about its author.’ (Charnavel and Sportiche 2016: 49)

-

a.

The goal of this article, which will concentrate on English reflexives (leaving the investigation of reciprocals and crosslinguistic anaphors for future research), is to solve the long-standing puzzle posed by English PNAs by integrating these various perspectives.Footnote 5 As we will see, each of these theories provides valuable insight into the puzzle, but misses at least one crucial aspect of it. Instead, we propose a new combination of mostly existing ingredients that leads to a full solution to the PNA puzzle without assigning an exceptional status to PNAs.

In line with Chomsky (vs. PBTs), we argue that English PNAs, just like any anaphor, are uniformly subject to Binding Theory: Condition A suffers no exception (and is antecedent-based). We also agree with PBTs (vs. Chomsky) that, descriptively speaking, anaphors exhibit a heterogeneous behavior, being either plain or exempt. To resolve this apparent paradox, we adopt Charnavel’s (2020a, 2020b) hypothesis that the descriptive heterogeneity of anaphors can be reduced to the heterogeneity of their local binders. In particular, besides standardly postulated binders, anaphors—including PNAs—can take covert logophoric binders, which syntactically represent the locally relevant perspective center. Thus, anaphors that are descriptively exempt in fact covertly comply with Condition A.

Charnavel’s logophoric A-binder solution is not sufficient to fully solve the English PNA puzzle, however. As we will see, there is another factor at stake—hinted at by both Chomsky and PBTs, albeit in very different ways—which further complexifies the superficial behavior of PNAs: as shown by (5b) (vs. (5a)), English anaphors cannot always be logophorically bound even under appropriate discourse conditions. We will attribute this fact to an independent constraint, which, descriptively, blocks logophoric binding in the presence of a coargument subject. The theoretical relevance of subject coargumenthood for English reflexives—outside PBTs—is demonstrated in Ahn (2015), which distinguishes anaphors that are bound by a coargument subject from other anaphors on the basis of prosody-based diagnostics. To explain the blocking of logophoric binding in sentences like (5b), we propose to complement this insight with a strong/weak competition hypothesis à la Cardinaletti and Starke (1999): the apparent competition between some binders (i.e. logophoric binder and coargumental subject) in fact results from a competition between some possible bindees (strong herself vs. weak herself and weak her), which falls under a general competition principle between weaker and stronger forms. This hypothesis thus partly reintegrates in the account of PNAs both the relevance of coargumenthood, which is at the root of PBTs, and the possible presence of implicit PRO-like subjects within nominals, which is crucial to the Chomskian theory.

In sum, the seemingly heterogeneous distribution of the descriptive class of English PNAs illustrates how the interaction between simple and general principles—Condition A, logophoricity, weak/strong competition—can yield superficially complex behaviors. Such apparent complexity, in our opinion, does not warrant a relaxation of parsimony or rule generality, but a disentanglement of the various interacting factors.

The outline of the paper is as follows. The first part (i.e. Section 2) will re-examine the various properties purported to distinguish between plain and exempt anaphors in order to determine which of these properties actually characterize English PNAs in various syntactic contexts. To this end, we will mainly follow the proposals of Charnavel and Sportiche (2016) and Charnavel (2020a, 2020b) in order to independently determine the local domain relevant to PNA binding as well as the notion of logophoricity relevant to apparent exemption. This empirical exploration will motivate unification of the descriptively double (plain/exempt) behavior of English PNAs by adapting Charnavel’s (2020a, 2020b) logophoric A-binder hypothesis, which reduces exempt to plain behavior (as roughly represented in (9b) as compared to (9a)).

-

(9)

-

a.

... [XP DPi X ... picture of herselfi ... ]

-

b.

... (DPi) ... [XP prolog-i DPk X ... picture of herselfi ...]

-

a.

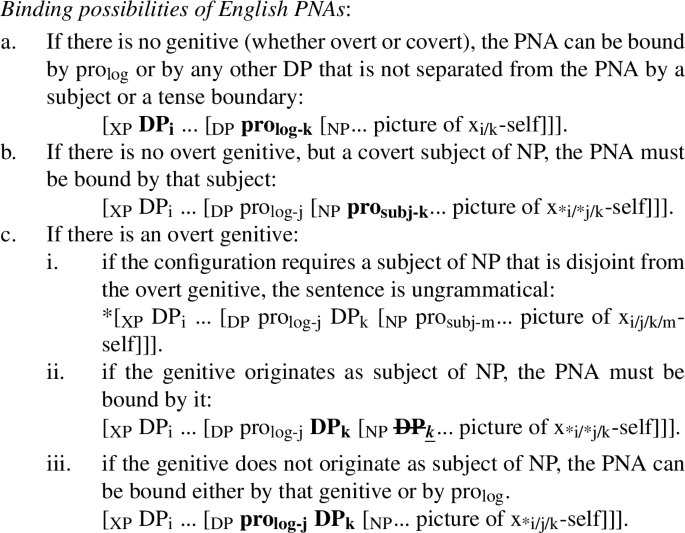

In the second part of the paper (i.e. Section 3), we will investigate the blocking of logophoric binding by the presence of (overt or covert) coargument subjects (i.e. explore the conditions of application of cases (10a) vs. (10b)).

-

(10)

-

a.

... (DPi) ... [XP prolog-i DPk X [NP ... picture of herselfi ...]]

-

b.

... (DPi) ... [XP ... [NP DPi/prosubj-i picture of herselfi ...]]

-

a.

To establish the generalization, we will first concentrate on the verbal domain, where the obligatory overtness of subjects removes a complicating factor. The generalization will be explained using Ahn’s (2015) discovery about the prosodic behavior of anaphors bound by coargument subjects along with Cardinaletti and Starke’s (1999) general principle of competition between weaker and stronger forms. We will then come back to the nominal domain, where we will explore the consequences of this competition when the possible implicitness of nominal subjects is added to the general picture.

2 Unifying plain and exempt PNAs: The logophoric A-binder hypothesis

English PNAs have received specific attention in the literature because, unlike other anaphors, they seem to be generally exempt from the structural conditions of locality defined by Condition A of Binding Theory. The goal of this section is to challenge this claim on both descriptive and analytical levels. Descriptively (Sect. 2.1), we show that PNAs can in fact be plain or exempt; we reach this conclusion by re-examining their distribution using a criterion independent of Condition A (i.e. Charnavel and Sportiche’s 2016 inanimacy-based tool) to distinguish between plain and exempt instances of anaphors. Analytically (Sect. 2.2), we propose that PNAs are in fact never exempt, but consistently obey Condition A; we obtain this result by adopting Charnavel’s (2020a, 2020b) logophoric A-binder hypothesis, which reduces exempt behavior to local binding by an implicit logophoric binder. This hypothesis correctly predicts the descriptively dual behavior of English PNAs while avoiding postulation of any kind of homophony or restriction of the scope of Condition A.

2.1 The descriptively dual behavior of English Picture Noun Anaphors (PNAs)

2.1.1 PNAs in possessorless DPs

In this section, we concentrate on the prototypical case of PNAs, namely reflexives in picture noun phrases that lack a possessor (henceforth possessorless PNAs). We show that, descriptively speaking, they are neither uniformly plain anaphors as implied by the Chomskian theory, nor uniformly exempt anaphors as implied by predicate-based theories, but in fact exhibit a dual behavior. Recall that by plain anaphors, we mean anaphors that standardly obey Condition A and by exempt anaphors, anaphors that seem to disobey Condition A; as we will see, the content of these terms thus depends on the definition of Condition A. The bulk of our argumentation challenging the earlier literature will therefore consist in independently determining the scope of Condition A and conditions on exemption.

2.1.1.1 Exceptional distributional properties of possessorless PNAs

As previewed in Table 1 and detailed below, possessorless PNAs are usually claimed to exhibit four distributional properties that distinguish them from plain anaphors (see Bouchard 1984; Lebeaux 1984; i.a.). It is generally assumed that possessorless PNAs are not unique in this respect, but share these characteristics with other instances of anaphors, in particular those within a conjoined DP (e.g. Mary and herself), within like-phrases (e.g. physicists like herself), within as for-phrases (e.g. as for herself) or within exceptive constructions (e.g. no one but herself) (see Ross 1970; Kuno 1972, 1987; Keenan 1988; i.a.).

First, as mentioned at the start, it has been observed that possessorless PNAs need not be locally bound (see Helke 1970; Ross 1970; Jackendoff 1972; Cantrall 1974; Lebeaux 1984; Bouchard 1984; Kuno 1987; Zribi-Hertz 1989; Pollard and Sag 1992; Reinhart and Reuland 1993; i.a.). Example (11) below shows that himself need not be c-commanded by its antecedent; example (1) above illustrates that the antecedent of himself does not have to be in the smallest clause containing it, and example (12) that the antecedent does not even have to be within the same sentence. These reflexives thus appear to escape the locality conditions on anaphors under any definition of locality.

-

(11)

The picture of himselfi in Newsweek dominated Johni’s thoughts. (Pollard and Sag 1992: 278)

-

(12)

Johni was going to get even with Mary. That picture of himselfi in the paper would really annoy her, as would the other stunts he had planned. (Pollard and Sag 1992: 274)

Importantly, these examples remain apparent exceptions to the Chomskian Condition A even if we extend Chomsky’s PRO-based solution to them.Footnote 6 Recall that in (3)–(4) above, Chomsky posits that the DP containing the picture noun can include a PRO-like subject, thereby allowing the object pronoun to corefer with an apparently local antecedent. If we adopt this hypothesis, we might further assume that the PRO-like subject can serve as the local binder of an anaphor. Extending this to examples like (1), (11) or (12), we may conclude that the appearance of exemption follows from local binding by the null nominal subject; this in turn would imply that in such examples, it is the referent of the antecedent of the reflexive that took the picture.Footnote 7 But crucially, these examples do not require this type of interpretation: for instance, (11) is perfectly acceptable in a context where John did not take the picture—in fact, this is the most natural interpretation. That is not to say that Chomsky’s hypothesis must be abandoned without further discussion. We will see in Sect. 3.2.3 that it is in fact part of the solution. But the acceptability of these examples under a non-agentive interpretation of the antecedent shows that an extension of Chomsky’s hypothesis is not sufficient to account for all instances of non-locally bound PNAs. The aim of this first part of the paper (i.e. Section 2) is to investigate the cases that cannot fall under the Chomskian explanation; unless otherwise stated, all examples should therefore be read under the aforementioned non-agentive interpretation.

Second, possessorless PNAs are claimed to contrast with plain anaphors in allowing split antecedents (see Helke 1970; Bouchard 1984; Lebeaux 1984; Pollard and Sag 1992; i.a.).

-

(13)

-

a.

Johni told Maryk that there were some pictures of themselvesi+k inside.

-

b.

*Johni told Maryk about themselvesi+k. (Lebeaux 1984: 346)

-

a.

Third, it is often assumed that possessorless PNAs can trigger sloppy or strict readings in ellipsis contexts, while plain anaphors only exhibit sloppy readings (see Bouchard 1984; Lebeaux 1984; Reinhart and Reuland 1993; Kiparsky 2012; Runner et al. 2002; i.a.).

-

(14)

Johni thought that there were some pictures of himselfi inside, and Bill did too.

-

a.

Bill thought that there were some pictures of himself inside too.

-

b.

Bill thought that there were some pictures of John inside too. (Lebeaux 1984: 346)

-

a.

-

(15)

Johni hit himselfi, and Bill did too.

-

a.

Bill hit himself too.

-

b.

#Bill hit John too. (Lebeaux 1984: 346)

-

a.

Finally, it is commonly supposed that possessorless PNAs, unlike plain anaphors, are in free variation with pronouns (see Jackendoff 1972; Lebeaux 1984; Chomsky 1986; i.a.).

-

(16)

-

a.

Johni knew that there were some pictures of {himselfi/himi} inside.

-

b.

Johni likes {himselfi/*himi}. (Lebeaux 1984: 346)

-

a.

2.1.1.2 Possessorless PNAs as exempt under PBTs’ approach to exemption

These four purported distributional properties of PNAs and other instances of anaphors, which are properties of pronouns, have caused a widespread and persistent assumption that PNAs are in fact not real anaphors, but pronouns (see Bouchard 1984; Safir 2004; Drummond et al. 2011; Rooryck and Vanden Wyngaerd 2011; i.a.). However, this hypothesis implies some kind of lexical ambiguity or homophony: English herself would have two—related—lexical entries, one for plain behavior, one for exempt behavior. This assumption clearly goes against parsimony, especially since the generalization holds cross-linguistically: it is not just in English, but also in many other unrelated languages like Chinese, Korean or Turkish, that reflexives exhibit a dual behavior (see review in Charnavel 2020a).

Instead of postulating homophony between an anaphor herself and a pronoun herself, PBTs (Pollard and Sag 1992; Reinhart and Reuland 1993; i.a.) develop a theory of exemption that restricts the scope of Condition A. Under these proposals, Condition A, which is redefined as a condition on predicates rather than a condition on antecedence, requires that anaphors be bound by a syntactic coargument whenever they have one.Footnote 8 Crucially, this implies that anaphors lacking a coargument, such as possessorless PNAs that are the only argument of the picture noun, are exempt from Condition A. Such exempt anaphors, PBTs argue, are instead subject to discourse conditions related to perspective.Footnote 9,Footnote 10 Indeed, it has long been observed that possessorless PNAs and other exempt anaphors are licensed in clauses expressing the point of view of their antecedent (Kuroda 1965, 1973; Cantrall 1969, 1974; Kuno 1972, 1987; Clements 1975; Sells 1987; Zribi-Hertz 1989, i.a.). This generalization, exemplified by the contrast between (1) and (7) above, is also illustrated by the contrast between (12) and (17).

-

(17)

Mary was quite taken aback by the publicity Johni was receiving. That picture of him(*selfi) in the paper had really annoyed her, and there was not much she could do about it. (Pollard and Sag 1992: 274)

PBTs thus directly account for the first distributional property of possessorless PNAs mentioned above: possessorless PNAs need not be locally bound since, in the absence of a coargument, they are exempt from Condition A. The second property of PNAs, namely the acceptability of split antecedence, also follows from PBTs, according to Pollard and Sag (1992: 270): exempt anaphors, which are not subject to Condition A, are free to refer to a group entity formed in the discourse, regardless of whether this entity is expressed as a single DP in the syntax. The availability of strict readings, Reinhart and Reuland (1993: 674) claim, is also accounted for under their theory (complemented with Rule I; see e.g. Grodzinsky and Reinhart 1993): possessorless PNAs, which are exempt from Condition A, can be related to their antecedent either by variable binding or by coreference, whereas anaphors with a coargument, which obey Condition A and must thus be coindexed with a coargument, can only be interpreted by variable binding. As for non-complementarity between PNAs and pronouns, it is also predicted by PBTs: given that PBT Condition B forbids pronouns from being bound by coarguments, it follows that exempt anaphors, which by definition lack a coargument, can alternate with pronouns (under appropriate discourse conditions). Furthermore, the distinction between syntactic and semantic coarguments made by Reinhart and Reuland (1993) explains the contrast between (3), where the PNA alternates with the pronoun, and (4), where it does not: in sentences like (4), the pronoun, unlike the reflexive, is ruled out by the semantic representation of the agent role associated with the picture noun, because only Condition B (vs. Condition A) is sensitive to semantic co-argumenthood.Footnote 11

2.1.1.3 Possessorless PNAs as plain or exempt under Charnavel and Sportiche’s (2016) approach to exemption

Because PBTs redefine Condition A as obligatory coargument binding, the core property held to be responsible for the exempt behavior of possessorless PNAs is their lack of a coargument. As argued in detail in Charnavel and Sportiche (2016) based on French anaphors, this approach to exemption is empirically incorrect; we confirm this conclusion for English PNAs below. Instead, Charnavel and Sportiche (2016) propose a criterion independent of Condition A to descriptively tease apart plain and exempt anaphors, namely inanimacy. Their reasoning is based on the widespread observation (also adopted by PBTs) that, cross-linguistically, exempt reflexives are subject to logophoric conditions, i.e. their clause must express the point of view of their antecedent (see aforementioned references). Given the controversial and often imprecise definition of logophoricity (see review in Charnavel 2020a), this notion cannot be directly used to detect exempt anaphors. But non-logophoricity, Charnavel and Sportiche (2016) argue, can conversely be used to identify plain anaphors. Specifically, they hypothesize that inanimate anaphors cannot be logophoric, as by nature they lack a mental state, which is required to take perspective under (virtuallyFootnote 12) all definitions of logophoricity, and therefore are not eligible for exemption.

This inanimacy-based tool can be used to re-examine the distributional properties of English possessorless PNAs (cf. Bassel 2018 on Hebrew). It reveals that, contrary to the predictions of PBTs, possessorless PNAs do not consistently exhibit an exempt behavior. First, inanimate possessorless PNAs do obey locality conditions:Footnote 13 unlike himself in (1), (11) or (12) above, itself must be bound (see (18a) vs. (18c)) and cannot be bound across a subject (see (18a) vs. (18b)).Footnote 14

-

(18)

-

a.

[The witty play]i inspired a parody of itselfi.

-

b.

*[The witty play]i inspired {many theaters/Bob} to present a parody of itselfi.

-

c.

*The controversies surrounding [the witty play]i inspired a parody of itselfi.

-

a.

Second, inanimate possessorless PNAs must be exhaustively bound. For example, unlike animate themselves in (13) and (19b), inanimate themselves in (19a) cannot take a split antecedent.

-

(19)

-

a.

*After the renovation of [the castle]i, [the museum next to it]k had pictures of themselvesi+k printed.

-

b.

After Johni graduated high school, [his mom]k had pictures of themselvesi+k printed.

-

a.

These distributional differences between inanimate and animate possessorless PNAs are not predicted by PBTs, according to which possessorless PNAs should uniformly be exempt, whether animate or not, since they lack a coargument. Certainly, PBTs argue that exempt anaphors are subject to perspective-related discourse conditions, which could presumably rule out examples (18b–18c) and (19a) (as we will in fact argue in Sect. 2.2.1). But crucially, examples like (18a) (see also (21)–(22) and (24) below) should similarly be ruled out under PBTs since they also contain non-perspectival anaphors without coarguments. Application of the inanimacy-based tool to possessorless PNAs thus reveals that the dividing line between plain and exempt anaphors should not be based on coargumenthood. In fact, all the observations above also hold for all other types of anaphors without coarguments, as shown in (20), for example.

-

(20)

-

a.

[The witty play]i refers to itselfi and its author.

-

b.

*[The witty play]i led {Bob / newspapers} to provide information about itselfi and its author.

-

a.

The correct descriptive generalization, then, should be formulated as follows: all inanimate anaphors must be locally and exhaustively bound, but some animate anaphors (i.e. perspectival ones, see Sect. 2.2.1) need not be locally or exhaustively bound. Possessorless PNAs are not special in any way, but exhibit this dual plain/exempt behavior accordingly.

With respect to the remaining two purported distributional properties of exempt anaphors, inanimate possessorless PNAs pattern with animate ones: as illustrated in (21)–(22), they can trigger strict readings and alternate with pronouns. As we show below, this fact does not indicate that possessorless PNAs are exempt, but rather, that these two properties do not accurately distinguish exempt from plain anaphors.

-

(21)

[The castle]i contains more replicas of itselfi than the museum does [contain replicas of iti].

-

(22)

[This mysterious ruin]i inspires many legends about iti(self).

First, it is not the case that plain anaphors only trigger sloppy readings, whether we adopt a predicate-based or a Chomskian version of Condition A. Pollard and Sag (1992: 270, fn. 9) argue that a strict interpretation is favored in examples like (23), even if himself has a coargument (see more such examples in Dahl 1973; Sag 1976; Fiengo and May 1994; Hestvik 1995; Kehler 2002; Büring 2005; as well as in recent experiments like Frazier and Clifton 2006; Kim and Runner 2009; Ong and Brasoveanu 2014; McKillen 2016).Footnote 15

-

(23)

If Johni doesn’t prove himselfi to be innocent, I’m sure that the new lawyer hei hired will [prove himi to be innocent].

Furthermore, the same observation crucially holds with inanimate anaphors as shown in (24). This reveals that the availability of strict readings in examples like (23) is not due to the anaphor being exempt (from Chomskian Condition A) due to their perspectival potential.

-

(24)

Mercuryi attracts itselfi less than silver does [attract iti].

Charnavel and Sportiche’s (2016) inanimacy-based tool thus reveals that exemption is irrelevant to the availability of strict readings (though what factors are relevant remains to be found).

Second, it is not the case either that plain anaphors are in complementary distribution with pronouns—neither under PBTs, nor under Charnavel and Sportiche’s (2016) proposal. Inanimate anaphors, whether or not they have a coargument, can alternate with pronouns, as illustrated in (25) (see more examples in Cantrall 1974; Minkoff 2000; Charnavel 2020a; i.a.).

-

(25)

[That magnet]i attracts paper clips to iti(self). (Minkoff 2000: 584–585)

Just as in the case of strict readings, we will not provide an explanation for this fact here, which bears on Condition B of Binding Theory; the observation that non-complementary distribution with pronouns, just like strict readings, is not a specific property of exempt anaphors, is sufficient for our purposes. But note that the fact illustrated in (25) (and more generally, our whole paper) is consistent with the standard hypothesis that pronouns must be disjoint from local binders (Condition B) and further supports the idea that the local domain relevant to Condition B is smaller than the local domain relevant to Condition A (Huang 1983; Chomsky 1986; i.a.; see fn. 24, 31, 51 and Sect. 3.2.3 for some further discussion about Condition B).

In sum, only two distributional properties reliably distinguish exempt from plain anaphors, as summarized in Table 2.

Crucially, in contrast with the predictions of both Chomskian Binding Theory and PBTs, possessorless PNAs can behave as plain or exempt with respect to these two properties. The descriptive generalization we have reached in this section is thus the following:

-

(26)

Descriptive generalization about possessorless PNAs:

Inanimate PNAs must be bound exhaustively and locally (i.e. within the smallest tensed TP containing them, without any subject intervening between them and their antecedent), whereas some animate PNAs need not be.

This generalization matches the generalization that Charnavel and Sportiche (2016) formulate on the basis of French inanimate anaphors in general (not just PNAs), which leads them to redefine Condition A as in (27).Footnote 16

-

(27)

Condition A (Charnavel and Sportiche 2016: 71):

A plain anaphor must be bound within the minimal spellout domain containing it (i.e. tensed TP, or any other XP with a subject distinct from the anaphor).

We will therefore adopt the definition of Condition A given in (27) for the remainder of our investigation of English PNAs. Note that we will not attempt to derive Condition A, as only the generalization about the binding domain of anaphors is relevant to our purposes. But as discussed in Charnavel and Sportiche (2016, Sect. 5.4.3), this formulation is compatible with movement-based approaches to binding (see Drummond et al. 2011; Kayne 2002; Charnavel and Sportiche to appear; i.a.).

2.1.2 PNAs in possessed DPs

2.1.2.1 Locality constraints of possessed PNAs in previous studies

As mentioned above, the distribution of English PNAs is typically discussed in configurations in which the reflexive is the only phrase within the DP. In particular, overt possessors are usually excluded from examples involving PNAs because it is traditionally assumed that only possessorless PNAs exhibit an exceptional behavior. In fact, Chomsky’s solution for (3)–(4) relies on a comparison with (28)–(29), which contain an overt possessor and are treated as baseline examples. Under the Chomskian theory, the presence of an overt possessor (in the specifier of DP) restricts the binding domain of a PNA to the DP containing it; PNAs in possessed DPs (henceforth, possessed PNAs) can thus only be bound by the possessor, as in (30).

-

(28)

-

a.

*Theyi heard [my stories about [each other]i].

-

b.

Theyi heard [my stories about themi]. (Chomsky 1986: 166)

-

a.

-

(29)

-

a.

* Theyi told [my stories about [each other]i].

-

b.

Theyi told [my stories about themi]. (Chomsky 1986: 166–167)

-

a.

-

(30)

Theyi {heard/told} [theiri stories about [each other]i].

Possessed PNAs have received more attention in PBTs. In early versions of the theory (Pollard and Sag 1992; Reinhart and Reuland 1993), possessed PNAs are treated as plain anaphors (just like under the Chomskian theory) on the basis of reported contrasts like (6a) vs. (6b) above or (31a) vs. (31b) below. These contrasts are predicted under PBTs by the hypothesis that the possessor is a subject of the nominal predicate.Footnote 17

-

(31)

-

a.

Johni’s description of himselfi was flawless.

-

b.

*The fact that Maryk’s description of himselfi was flawless was believed to be disturbing Johni. (Pollard and Sag 1992: 265)

-

a.

But these contrasts are not robust, as already suggested in Reinhart and Reuland (1993: 683, citing Ben-Shalom and Weijler 1990), prompting speculation therein that NPs may in fact never contain a subject, as proposed in Williams (1985).Footnote 18 Many experimental studies (Asudeh and Keller 2001; Keller and Asudeh 2001; Runner et al. 2002, 2003, 2006; Jaeger 2004; Runner and Kaiser 2005; i.a.) have since confirmed that possessed PNAs can be bound from outside their picture NP. For example, the magnitude estimation task used by Keller and Asudeh (2001: 7) revealed no significant acceptability difference between (32a) and (32b), which are both highly acceptable.

-

(32)

-

a.

Hannahi found Peterk’s picture of herselfi.

-

b.

Hannahi found Peterk’s picture of heri. (Keller and Asudeh 2001: 5)

-

a.

According to these experimental studies, the empirical observations in (32) do not challenge PBTs but, rather, the status PBTs assign to the possessor. Building on Williams (1985) and Barker (1995), Asudeh and Keller (2001) argue that the possessor is not an argument of the head noun (cf. Keller and Asudeh 2001; Runner and Kaiser 2005; i.a.). Under that revised assumption, possessed PNAs do not have any coarguments. They are thus predicted to be exempt and, therefore, able to take an antecedent outside their DP (under appropriate discourse conditions).

Inspired by Reinhart and Reuland (1993: fn. 49) and Runner (2007), Reuland (2011: 254) presents another solution to the issue, which relies on a modification of PBT Condition A: obligatory coargument binding only applies to eventive predicates.Footnote 19 What this hypothesis predicts for PNAs depends on the extent to which (some) picture nouns can be treated as eventive. Reuland (2011: 254–255, 381–382, fn. 7–8) does not investigate in detail the question, but suggests three possibilities. Under the first option, nouns never have an eventive role, which makes the same prediction as the previous hypothesis: all possessed PNAs are exempt. Under the second option, only Grimshaw’s (1990) complex event nominals (i.e. nouns that have an internal aspectual analysis) are eventive; this predicts that possessed PNAs are generally exempt, except for anaphors in complex event nominals. This prediction is supported by the contrast between sentences like (32a) and sentences like (33a–33b).Footnote 20

- (33)

Finally, under the third option, only concrete nominals, which denote a physical object, lack an event role. Concrete nominals contrast not only with complex event nominals, but also with result nominals, which denote the outcome of an event. Applied to picture nouns, the concrete/result distinction tracks with a distinction in sense (see Davies and Dubinsky 2003): picture nouns pattern with concrete nominals when referring to a physical object, but pattern with result nominals when referring to informational content. Hence, this third option predicts that possessed PNAs are exempt only when the picture noun is object-referring. Reuland (2011) mentions as support for this hypothesis the contrast between (34a) and (34b), noted in Runner (2007: 83).Footnote 21

-

(34)

-

a.

✓/?Joei destroyed Harryk’s book about himselfi.

-

b.

?/*Joei wrote Harryk’s book about himselfi. (Runner 2007: 84)

-

a.

In sum, while the Chomskian theory and early PBTs predict possessed PNAs to be obligatorily bound by the possessor due to Condition A, later PBTs consider either all possessed PNAs (Keller and Asudeh 2001; Runner and Kaiser 2005; i.a.) or only non-eventive possessed PNAs (Runner 2007; Reuland 2011; i.a.) to be exempt from Condition A.

2.1.2.2 Re-examining the locality constraints of possessed PNAs

The difficulty in pinning down the status of possessed PNAs is due to the controversy surrounding several variables simultaneously: the definition of Condition A, the potential conditions for exemption from it, the status of the so-called possessor. As in the case of possessorless PNAs, Charnavel and Sportiche’s (2016) inanimacy-based tool can be used to at least partially settle the issue by providing a criterion independent of Condition A to tease apart plain and exempt anaphors.Footnote 22

Specifically, the inanimacy-based tool can be used to test the hypothesis of late PBTs that possessed PNAs are exempt (at least with non-eventive nouns; see Sect. 2.1.2.1). Recall that PBTs take anaphors to be exempt in the absence of syntactic coarguments, and that exempt anaphors are assumed to be subject to discourse conditions relating to perspective; hence, if the possessor does not comprise a syntactic coargument of a possessed PNA, then possessed PNAs are predicted to be licensed only if logophoric. Given that, as we saw, inanimates are non-perspectival and thus ineligible for exemption, this hypothesis would entail that inanimate possessed PNAs should never be acceptable (at least with non-eventive nouns). But the contrast between (35) and (36) shows that this prediction is not borne out: only inanimate possessed PNAs that are bound across the possessor are unacceptable.Footnote 23 This is true even in concrete nominals ((35b) vs. (36b)), contrary to the most conservative hypothesis of Reuland (2011), under which only concrete nouns are treated as non-eventive.

-

(35)

-

a.

*[The castle]i looks very different from Mary’s replica of itselfi.

-

b.

*[The castle]i collapsed on Mary’s replica of itselfi.

-

a.

-

(36)

-

a.

Mary was impressed by [the castle]i’s replica of itselfi.

-

b.

Mary polishes [the castle]i’s replica of itselfi.

-

a.

Hence, it is neither the case that possessed PNAs uniformly behave as exempt, nor that the locality constraints on possessed PNAs depends on the nature of the noun predicate, as implied by the latest PBTs. Rather, the behavior observed of possessed PNAs depends on the logophoric potential of the reflexive: just like possessorless PNAs, possessed PNAs exhibit a dual behavior (plain vs. exempt), irrespective of the interpretation of the picture noun. Specifically, non-perspectival PNAs like itself in (35)–(36) must be bound by the possessor, while perspectival PNAs like himself/herself in (32a) and (34a) need not be bound by the possessor. This observation supports the Chomskian notion of locality revisited by Charnavel and Sportiche (2016): the presence of a so-called possessor does turn the DP into a binding domain. This is not due to the argumental status of the possessor as implied by early PBTs (and correctly questioned by late PBTs; see discussion in Sect. 3.2.2). Rather, formation of a binding domain follows from the position of the possessor in the specifier of DP, which entails the formation of a spellout domain (see Charnavel and Sportiche 2016).

This conclusion about the dual behavior of possessed PNAs is further supported by the observation that non-exhaustive binding of possessed PNAs is only possible with animates.Footnote 24

-

(37)

-

a.

Maryi looks like Suek in the library’s picture of themselvesi+k.

-

b.

*[The museum]i looks like [the castle]k in the library’s picture of themselvesi+k.

-

a.

-

(38)

-

a.

Maryi will soon buy Suek’s sculpture of themselvesi+k.

-

b.

* [The castle]i will soon contain [the museum]k’s replica of themselvesi+k.

-

a.

As captured by the contrasts in (37) and (38), possessed PNAs can behave as exempt by licensing split antecedents if animate (cf. Helke 1970: 116), but exhibit plain behavior by requiring exhaustive binding if inanimate: whether the picture noun is interpreted as a result nominal (as in (37b)) or a concrete nominal (as in (38b)), split antecedents for inanimate PNAs are ruled out.

Thus, possessed PNAs are no different from possessorless PNAs in displaying both plain and exempt behavior (see generalization (26)) as summarized in Table 3.

2.2 The analytically uniform behavior of English PNAs: Extending the logophoric A-binder hypothesis

In Sect. 2.1, we showed that just like any anaphor, both possessorless and possessed PNAs can descriptively behave as plain or exempt anaphors. We obtained this result by applying Charnavel and Sportiche’s (2016) inanimacy-based tool, which allowed us to determine the distributional properties distinguishing exempt from plain anaphors in a reliable way. This result challenges all previous theories: first, contrary to Chomskian predictions, PNAs can superficially be exempt from Condition A even under non-agentive interpretations, that is, when the referent of the anaphor is not the author of the picture; second, contrary to PBTs, the dividing line between plain and exempt anaphors does not lie in the presence of a coargument (whether the possessor counts as such or not), but in the perspectival interpretation of the anaphor; finally, contrary to the pervasive assumption represented by the claim in Drummond et al. (2011) above, that PNAs are logophoric pronouns (homophonous with anaphors), PNAs do not uniformly display pronominal properties, but can behave like plain anaphors.

The goal of the present section is to account for this apparently dual behavior of PNAs without appealing to homophony or restricting the scope of Condition A. We will reach this goal by adopting Charnavel’s (2020a, 2020b) logophoric A-binder hypothesis—thereby further supporting it by demonstrating that it also makes correct predictions for English PNAs. In the spirit of Chomsky (1986), this hypothesis retains the general applicability of Condition A by assuming the possible presence of implicit binders for anaphors. However, it introduces a new type of covert binder, which, unlike Chomsky’s PRO-like subject, does not entail an agentive interpretation, but derives the perspective-based contrasts observed above.

We begin by introducing Charnavel’s (2020a, 2020b) logophoric A-binder hypothesis in further detail in Sect. 2.2.1. Then, we extend this hypothesis to English PNAs: just as in Sect. 2.1, we will first concentrate on possessorless PNAs in Sect. 2.2.2, before applying the analysis to possessed PNAs, which raise further challenges, in Sect. 2.2.3.

2.2.1 The logophoric A-binder hypothesis

According to Charnavel’s (2020a, 2020b) hypothesis, descriptively exempt anaphors are in fact not exempt from Condition A, but are locally bound by a covert logophoric pronoun. Thus, the properties that characterize descriptively exempt anaphors do not come from the anaphors themselves, but derive from the nature of their binder.

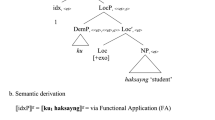

Recall from Sect. 2.1.1.3 (see (27)) that we adopt a version of Condition A according to which anaphors must be bound within the minimal spellout domain containing them. Based on the same assumption, Charnavel (2020a, 2020b) hypothesizes that each spellout domain can contain a verb-like logophoric operator OPLOG introducing a logophoric pronoun prolog as its subject. This is represented in (39a), in which prolog locally binds a PNA.

-

(39)

-

a.

(DPi)… [SPELLOUT DOMAIN ... [LogP prolog-i OPLOG [α … picture of herselfi …]]]

-

b.

[[ OPLOG ]] = λα.λx. α from x’s first person perspective (adapted from Charnavel 2020b: 679)

-

a.

Note that the category of the spellout domain shown in (39a) will depend on the syntactic configuration in which the PNA occurs: if the DP containing the PNA also contains a subject, then the DP will be the spellout domain relevant for binding (and can contain prolog as a potential binderFootnote 25); if the DP lacks a subject, then the spellout domain will instead be the smallest phrase containing both the DP and a subject (or the smallest tensed TP containing the DP if the DP is the subject of a tensed TP). While prolog refers to the locally relevant logophoric center, OPLOG imposes the first-person perspective of that center on its complement α, as formulated in (39b). This hypothesis codes the intuition that the locally relevant perspective center, which is independently determined by a combination of syntactico-semantic and discourse factors, can be syntactically represented in each phase.

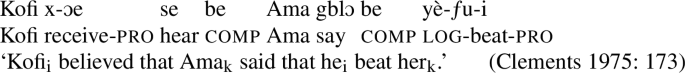

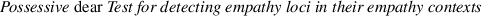

Charnavel’s hypothesis is inspired by the literature on logophoric operators and perspectival projections (see Koopman and Sportiche 1989; Kinyalolo 1993; Jayaseelan 1998; Speas and Tenny 2003; Adesola 2006; Anand 2006; i.a.), but differs from it in two main respects. First, it builds on Sells (1987) and Oshima (2006) in proposing a specific definition of logophoricity as first-person mental perspective (encompassing de se attitude and empathy) on the basis of anaphora-independent tests such as the epithet test for de se attitude shown in (40) and the French possessive cher test for empathy adapted to English in (41); this methodology circumvents the aforementioned issue regarding how to characterize the notion of logophoricity.

-

(40)

Epithet Test for detecting attitude holders in their attitude contexts:

To simultaneously check whether a given DP1 is in an attitude context and who the relevant attitude holder is, replace DP1 with an epithet and determine its referential possibilities in unmarked situations (i.e. without using non-de se scenarios). If there is a DP2 that does not locally-c-command the epithet but which the epithet cannot take as antecedent, then the epithet (and DP1 it replaced) are in an attitude context and the referent of DP2 is the attitude holder of that context. (cf. Charnavel 2020a: 146)

-

(41)

:

:To identify the possible empathy loci in a context containing a given DP, replace this DP with a possessive DP containing dear and determine its referential possibilities. If her dear is acceptable, its referent can be construed as the empathy locus of the context of the DP. Otherwise, only the speaker can be interpreted as the empathy locus. (cf. Charnavel 2020a: 169)

Second, it makes two modifications to the syntactic representation of logophoricity by restricting logophoric domains to spellout domains (instead of full CPs as previously assumed; see Charnavel 2020b: 709–711 for discussion) and by treating OPLOG as a verb-like operator introducing a subject (prolog); this twofold innovation crucially entails that prolog can serve as an A-binder for anaphors.

Under Charnavel’s hypothesis, apparently exempt anaphors like herself in (39a) are thus in fact bound locally (i.e. within their spellout domain) by the implicit logophoric pronoun prolog. This predicts that descriptively exempt anaphors must be logophorically interpreted, and thus derives (instead of postulating) the correlation between logophoricity and exemption observed in many unrelated languages (see e.g. French elle-même and son propre, Korean caki-casin, Mandarin ziji or Icelandic sig,Footnote 26 as discussed in aforementioned references and reviewed in Charnavel 2020a).Footnote 27

2.2.2 Possessorless PNAs

2.2.2.1 Testing for the logophoric interpretation of exempt PNAs

Applying Charnavel’s (2020a, 2020b) hypothesis to our specific case study, we propose that descriptively exempt English PNAs are analytically plain, covertly complying width Condition A by virtue of binding by prolog. This treatment entails that descriptively exempt PNAs must be logophorically interpreted (under a non-agentive interpretationFootnote 28) in the sense explained above. This correctly predicts our finding in Sect. 2.1.1.3 that inanimate PNAs are unacceptable unless locally bound by an overt binder: due to the incompatibility between inanimacy and mental perspective, inanimate PNAs cannot take prolog as an antecedent. As we will now illustrate with possessorless PNAs, this also correctly predicts that animate PNAs that lack an overt local binder can only occur in phrases expressing the first-person mental perspective of their antecedents.

This first means that seemingly exempt PNAs must pass the tests described in (40)–(41). For example, neither himself in the complement of the attitude verb believe in (1) (repeated as (42a)), nor himself in the intended Free Indirect Discourse in (12) (repeated as (43a)) can be replaced with a coreferential epithet, as shown in (42b)–(43b); this demonstrates that the antecedents of these anaphors are relevant attitude holders in the clause containing them.Footnote 29

-

(42)

-

a.

Tomi believes that there is a picture of himselfi hanging in the post office.

-

b.

*Tomi believes that there is a picture of [the idiot]i hanging in the post office.

-

a.

-

(43)

-

a.

Johni was going to get even with Mary. That picture of himselfi in the paper would really annoy her, as would the other stunts he had planned.

-

b.

#Johni was going to get even with Mary. That picture of [the idiot]i in the paper would really annoy her, as would the other stunts he had planned.

-

a.

Himself in (11) (repeated as (44a)) can be replaced by an epithet, as shown in (44b), but also by a possessive DP containing dear as in (44c); this reveals that its antecedent, John, cannot be construed as an attitude holder, but can be construed as the empathy locus in the phrase containing himself. However, himself in (7) (repeated as (45a)), which is unacceptable, can alternate with a coreferring epithet, but not (under a non-ironic reading) with a possessive DP including dear (see (45b–45c); this shows that the antecedent of himself neither refers to an attitude holder, nor to an empathy locus, which makes himself non-logophoric and unable to be bound by prolog.

-

(44)

-

a.

The picture of himselfi in Newsweek dominated Johni’s thoughts.

-

b.

The picture of [the idiot]i in Newsweek dominated Johni’s thoughts.

-

c.

The picture of hisi dear son in Newsweek dominated Johni’s thoughts.

-

a.

-

(45)

-

a.

*Mary said about Johni that there was a picture of himselfi in the post office.

-

b.

Mary said about Johni that there was a picture of [the idiot]i in the post office.

-

c.

Mary said about Johni that there was a picture of hisi (*dear) son in the post office.

-

a.

Second, the phrase containing exempt PNAs must express the first-person perspective of their antecedent. For instance, this predicts that himself in (42a), which refers to an attitude holder, must be read de se, as confirmed by (46).

-

(46)

Context: As a joke, Tom ran for a local election. Unexpectedly and unbeknownst to him, he got elected. What he knows is that the picture of the elected candidate, which he thinks is one of the other (serious) candidates, hangs in the post office.

Tomi believes that there is a picture of himi(#self) hanging in the post office.

Similarly, this implies that John’s act described in (43) must be considered as a stunt by John himself; for example, the sentence is infelicitous if only the speaker considers this act as a stunt, but John considers it as an act of kindness.

2.2.2.2 Deriving the distributional properties of exempt PNAs

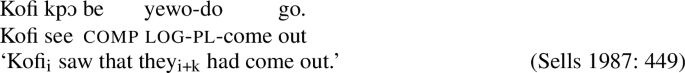

We have shown that the logophoric A-binder hypothesis correctly predicts the logophoric interpretations required for descriptively exempt PNAs. Adopting this hypothesis also allows us to derive the distributional properties that distinguish descriptively exempt from plain PNAs. As captured in (39) above, the apparent absence of locality constraints for exempt PNAs follows from the implicitness of their binder, prolog, which like any pronoun need not be locally bound nor even take an overt antecedent in the sentence.

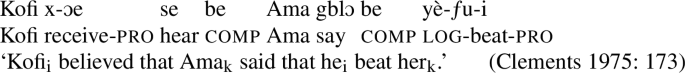

Similarly, the availability of non-exhaustive binding for exempt PNAs is an illusion due to the pronominal nature of their binder. As shown in (47) below (repeating example (13)), themselves, which descriptively takes a split antecedent (John and Mary), is in fact exhaustively bound by prolog. The pronominal nature of prolog, however, allows it to take a non-exhaustive antecedent; the Ewe example in (48) independently confirms that logophoric pronouns do not differ from other pronouns in this respect. Apparent non-exhaustive binding of the anaphor is thus analyzed as non-exhaustive antecedence of the exhaustive binder of the anaphor.

-

(47)

Johni told Maryk that prolog-i+k there were some pictures of themselvesi+k inside.

-

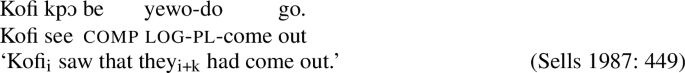

(48)

In sum, the logophoric A-binder hypothesis allows us to reduce descriptively exempt PNAs to plain anaphors by deriving all their specific properties from the nature of their binder prolog.

2.2.2.3 Independent arguments for the logophoric A-binder hypothesis

Charnavel (2020a, 2020b) provides additional arguments for the logophoric A-binder hypothesis independent of the properties of descriptively exempt anaphors. We show below that these arguments, which she uses to account for the distribution of French exempt anaphors, also apply to the case of English PNAs, thus further supporting extension of the logophoric A-binder analysis.

First, just like exempt anaphors in French (see Charnavel 2020a, 2020b) or Mandarin (see Pan 1997; Huang and Liu 2001; Anand 2006; i.a.), we observe that locally co-occurring exempt PNAs in English must exhaustively corefer. For example, (49) shows that even if himself (in (49a)) and themselves (in (49b)) can be descriptively exempt, they cannot co-occur in the same clause in (49c).

-

(49)

-

a.

Johni told Mary that there was a story about himselfi in the newspaper.

-

b.

Johni told Maryk that there were some pictures of themselvesi+k in the newspaper.

-

c.

* Johni told Maryk that there were some pictures of themselvesi+k and a story about himselfi in the newspaper.

-

a.

This ban on non-exhaustive coreference between locally co-occurring exempt PNAs directly follows from the logophoric A-binder hypothesis. Recall that under this hypothesis, descriptively exempt PNAs are in fact plain anaphors and must thus be exhaustively bound within their spellout domain. Given that there is only one possible binder in the spellout domain (TP) containing themselves and himself, namely prolog, both themselves and himself must be exhaustively bound by prolog, which entails that they must exhaustively corefer.Footnote 30 Whether prolog syntactically references John as the logophoric center in the embedded clause as in (51a) (cf. (50a)) or the sum of John and Mary as in (51b) (cf. (50b)), one of the anaphors will not be able to be exhaustively bound (namely, themselves in (51a) and himself in (51b)), thus ruling out the sentence.

-

(50)

-

a.

Johni told Mary that prolog-i there was a story about himselfi in the newspaper.

-

b.

Johni told Maryk that prolog-i+k there were some pictures of themselvesi+k in the newspaper.

-

a.

-

(51)

-

a.

*Johni told Maryk that prolog-i there were some pictures of themselvesi+k and a story about himselfi in the newspaper.

-

b.

*Johni told Maryk that prolog-i+k there were some pictures of themselvesi+k and a story about himselfi in the newspaper.

-

a.

Note that alternative hypotheses discussed above cannot explain this exhaustive coreference constraint. For example, under the hypothesis that PNAs are in fact logophoric pronouns subject to discourse requirements, ban on disjoint exempt anaphors in the same domain could presumably derive from a pragmatic principle ruling out perspective conflicts (cf. Pan 1997; Huang and Liu 2001, i.a.). But this explanation cannot hold for (49c), which does not involve disjoint, but partially coreferential anaphors, and thus does not entail perspective conflict, as attested by the perfectly viable direct discourse counterpart in (52).

-

(52)

John told Mary: “There were some pictures of us and a story about me in the newspaper.”

This coreference constraint cannot straightforwardly derive either from another version of this alternative hypothesis, according to which PNAs would be logophoric pronouns that must be bound by a logophoric operator (cf. Anand 2006) and at most one logophoric operator per clause can be present (cf. Koopman and Sportiche 1989). As mentioned above, nothing should prevent a logophoric pronoun from being partially bound; in fact, Adesola (2006) explicitly allows non-exhaustive binding by a logophoric operator. The restriction of one logophoric operator per clause does not therefore entail any ban on partially coreferring logophoric pronouns within the same clause.

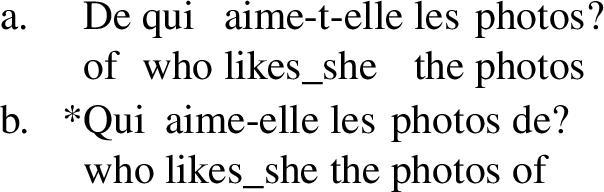

Second, the logophoric A-binder hypothesis predicts a Condition C effect if a descriptively exempt PNA locally co-occurs with an overt DP that refers to the logophoric center anteceding the anaphor (see Charnavel 2020a: 228). The contrast between (53a) and (53b) indicates that this prediction is borne out. As shown in (54), herself is licensed by the presence of prolog in its spellout domain (the bracketed DP), which syntactically represents the logophoric center, Lucy; the presence of the DP Lucy in the same domain therefore entails a Condition C violation.Footnote 31

-

(53)

-

a.

[Mean comments about herselfi on heri blog] hurt Lucyi’s feelings.

-

b.

*[Mean comments about herselfi on Lucyi’s blog] hurt heri feelings.

-

a.

-

(54)

[prolog-i Mean comments about herselfi on {heri/*Lucyi’s} blog] hurt {Lucyi’s/heri} feelings.

To wrap up, both anaphora-based and anaphora-independent arguments thus motivate the hypothesis that the possible syntactic representation of implicit logophoric pronouns, which can serve as A-binders, is responsible for the illusion of PNA exemption. This hypothesis parsimoniously reduces apparently exempt PNAs to plain anaphors subject to a fully general Condition A.

2.2.3 Possessed PNAs

2.2.3.1 The logophoric A-binder hypothesis applied to possessed PNAs

So far, we have focused our analysis on possessorless PNAs. Given that one of the motivations (and consequences) of the logophoric A-binder hypothesis is to unify all instances of anaphors, we also apply it to possessed PNAs, as illustrated in (55) and (56) (repeating (32a) and (37a), respectively).

-

(55)

Hannahi found [prolog-i Peterk’s picture of herselfi].

-

(56)

Maryi looks like Suek in [prolog-i+k the library’s pictures of themselvesi+k].

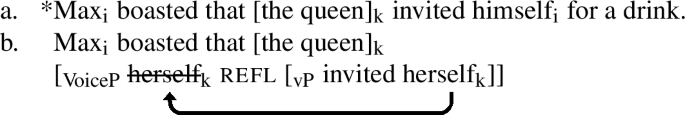

Just as in the case of possessorless PNAs, the acceptability of the descriptively exempt anaphor in these cases derives from the presence of prolog with an appropriate reference in its spellout domain, namely in the possessed DP; the relevant interpretation relies on whether the discourse conditions allow the intended antecedent of the anaphor to be construed as the logophoric center in the DP (e.g. as empathy loci in (55)–(56)).

Note that the logophoric center that is syntactically represented in a domain need not be the closest available one in the sentence, as shown by examples like (57) (containing an English exempt anaphor) or (58) (including an Ewe logophoric pronoun). Therefore, the presence of a disjoint animate possessor in sentences like (55) does not necessarily create an intervention effect (but may be responsible for some variability in judgments about possessed PNAsFootnote 32).

-

(57)

Johni asked Billk who hek thought had stolen the picture of himselfi. (Cantrall 1974: 95)

-

(58)

2.2.3.2 A remaining outstanding issue

The logophoric A-binder hypothesis thus seems to mostly solve the problem of picture noun anaphora: (60), which builds on (27), derives generalization (26), updated in (59).

-

(59)

Descriptive generalization (for all English anaphors including PNAs):

Non-perspectival anaphors must be locally and exhaustively bound, whereas perspectival anaphors may appear not to be.

-

(60)

Condition A: All anaphors (including PNAs) obey Condition A, i.e. must be bound within the minimal spellout domain containing them. Possible A-binders include overt DPs and covert ones such as PRO or prolog.

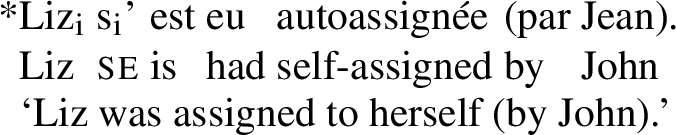

But the picture is not complete yet: a closer look at the data suggests that this solution is not sufficient. Specifically, we observe that in some configurations, possessed PNAs cannot be logophorically bound even under the appropriate discourse conditions; we will henceforth refer to this observation as the Logophoric Blocking Effect or LBE. This is first the case of PNAs in complements of creation verbsFootnote 33 such as himself in (61b) (repeating (34b), cf. (29a)).

-

(61)

-

a.

✓/?Joei destroyed Harryk’s book about himselfi.

-

b.

?/*Joei wrote Harryk’s book about himselfi.

-

a.

-

(62)

-

a.

*Johni took Mary’s pictures of himi.

-

b.

Johni found Mary’s pictures of himi. (Williams 1987: 156)

-

a.

The particular behavior of reflexives and pronouns (as in (62)) in this type of syntactic contexts has been long noticed in the literature (Jackendoff 1972: 166–168; Chomsky 1986: 166–167; Williams 1987: 155–156; Reinhart and Reuland 1993: 685; Runner 2002; Davies and Dubinsky 2003: 25–27; i.a.) and has more recently been experimentally investigated (Keller and Asudeh 2001; Jaeger 2004; Bryant and Charnavel 2020; i.a.). The logophoric A-binder hypothesis is too weak to account for the contrast in (61): just like in (55) above, it predicts that himself in (61b) can be bound by prolog, which should be able to refer to Joe, as implied by (61a). Another constraint must thus be responsible for ruling out (63).

-

(63)

*Joei wrote [prolog-i Harryk’s book about himselfi].

LBE also affects possessed PNAs in deverbal noun phrases like (64) or (65) (repeating (31b) and (33a)), which cannot be ruled out by the logophoric A-binder hypothesis.

-

(64)

*The fact that Maryk’s description of himselfi was flawless was believed to be disturbing Johni.

-

(65)

*Jilli found Mattk’s fear of herselfi surprising.

Finally, novel experimental findings presented in Bryant and Charnavel (2020) reveal that possessed PNAs cannot be logophorically bound either when they stand as the goal argument of the noun, as illustrated in (66).

-

(66)

*Chelseyi found Brandonk’s letter to herselfi. (Bryant and Charnavel 2020: 11–12)

In our view, these three types of data fall under the same category and demonstrate that an explanatory factor is yet to be added to the logophoric A-binder hypothesis to reach a full resolution of the PNA puzzle. The goal of the second and last part of the paper is to specify the nature of this additional factor that interacts with the logophoric A-binder hypothesis.

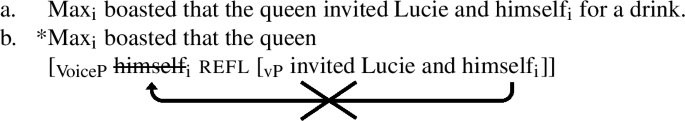

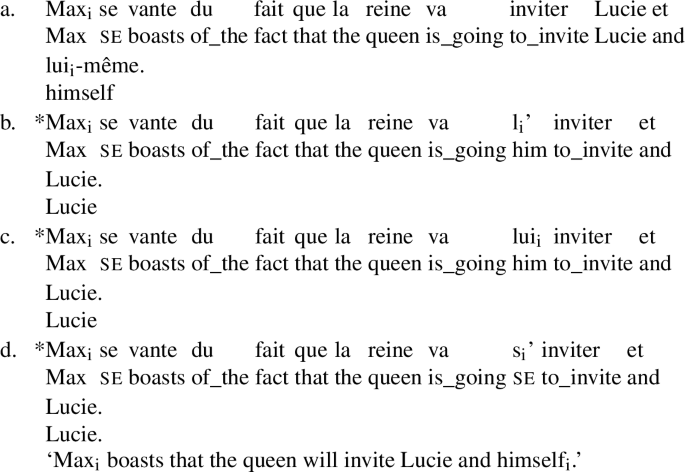

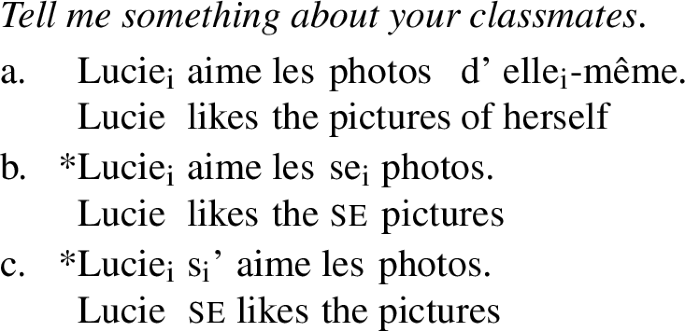

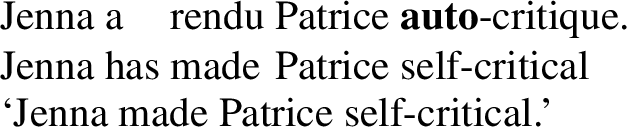

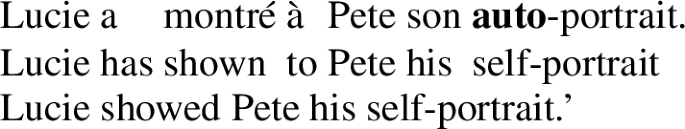

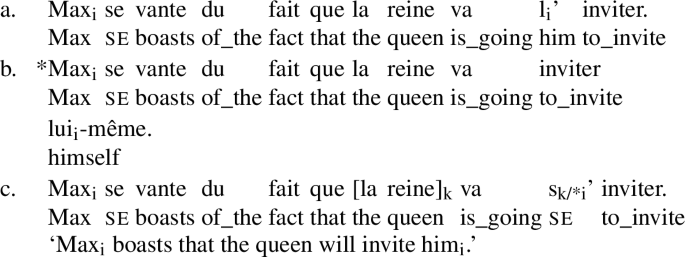

To give a preview, the additional factor that gives rise to LBE does not specifically target possessed PNAs: we hypothesize that the unacceptability of (63)–(66) results from the same constraint as the unacceptability of (5b) (vs. (5a)) repeated in (67b) (vs. (67a)), which involves a reflexive as direct object of the verb.

-

(67)

-

a.

Maxi boasted that the queen invited Lucie and himselfi for a drink.

-

b.

*Maxi boasted that the queen invited himselfi for a drink. (Reinhart and Reuland 1993: 670)

-

a.

The ungrammaticality of examples like (67b), which seems to be responsible for the widespread assumption of PNA exceptionalism, remains another crucial outstanding issue that appears to undermine the logophoric A-binder hypothesis beyond PNAs. Recall indeed from Sect. 2.1.1.1 that, typically, English anaphors can be descriptively exempt only under some configurations: in particular, when they are within picture noun phrases (e.g. picture of himself), as well as within a conjoined DP (e.g. Lucie and himself as in (67b)), within like-phrases (e.g. physicists like herself), within as for-phrases (e.g. as for herself) or within exceptive constructions (e.g. no one but herself). This observation is what motivated the development of PBTs, which tie exemption to the absence of coarguments. Now, we have explained at length (especially on the basis of inanimate anaphors) why it is empirically incorrect to base the dividing line between plain and exempt anaphors on coargumenthood. We therefore do not intend to reincorporate the notion of coargumenthood into our account of apparent exemption from Condition A. But we will show that, at least descriptively, this notion does indirectly play some role in the licensing conditions on reflexives.

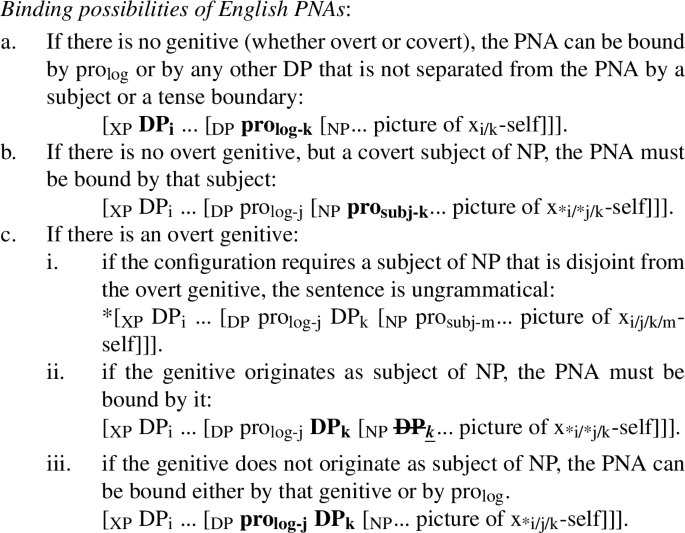

Specifically, we will conclude that the factor descriptively responsible for LBE in (67b) is the presence of a coargumental subject: the queen blocks logophoric binding in (67b), but not in (67a), because it is a subject coargument of himself only in (67b). And the reason why logophoric binding is excluded in the presence of coargumental subjects is because this configuration licenses alternative pronominal elements that are weaker and yield the same interpretation. We will thus hypothesize that LBE falls under a general principal of competition between weaker and stronger forms à la Cardinaletti and Starke (1999), which is fully independent of Condition A or exemption.

-

(68)

Logophoric Blocking Effect (LBE):

Herself cannot be logophorically bound in the presence of a coargumental subject.

-

(69)

Weak/strong competition (Cardinaletti and Starke 1999):

Weaker forms exclude stronger forms if they can yield the same interpretation.

Crucially, we will see that the same principle of competition can derive LBEs for PNAs in examples such as (63)–(66) once we clarify two issues specific to the nominal domain, namely the distinction between subjects of NP and other sources for possessors, and the conditions on implicit projection of nominal subjects. We will conclude that the ungrammaticality of (63)–(66) ultimately results from the obligatory presence of an implicit subject in NP in those cases. Besides solving the PNA puzzle, this investigation of LBE will thus provide a new probe into the controversial argument structure of NPs.

3 Deriving the logophoric blocking effect: The weak/strong competition hypothesis

This second part of the paper aims at explaining why the empirical scope of the logophoric A-binder hypothesis seems to be restricted, namely why logophoric binding is impossible for PNAs in some configurations, e.g. (63)–(66), in spite of favorable discourse conditions. First, we will explore such Logophoric Blocking Effects (LBEs) in the verbal domain, e.g. (67b): in Sect. 3.1, we will build on Ahn (2015) to establish the empirical generalization capturing the conditions under which LBEs arise for anaphors in verbal complements, and we will derive this generalization from a weak/strong principle of competition inspired by Cardinaletti and Starke’s (1999) work. Only then will we be in a position to examine the consequences of this hypothesis in the nominal domain, where it interacts with additional factors: in Sect. 3.2, we will examine its predictions for both possessorless and possessed PNAs and thus solve the remaining cases of LBEs, e.g. (63)–(66). We will thereby open new avenues for the investigation of nominal structures.

3.1 The logophoric blocking effect in the verbal domain

The goal of this section is to derive LBEs in the verbal domain (i.e. outside PNAs), where the generalization that will ultimately be relevant to PNAs is easier to establish in the absence of complicating factors specific to the nominal domain. In a nutshell, we will show, using prosody as a diagnostic, that logophorically bound herself is necessarily a strong form. Due to a principle of competition between weaker and stronger forms, LBEs therefore arise when anaphors occur in positions that can host weak elements, typically in positions with a coargumental subject.

We will begin in Sect. 3.1.1 by introducing Ahn’s (2015) empirical observations regarding the prosodic behavior of English reflexives. This allows us to distinguish two cases of descriptively plain English anaphors (i.e. anaphors that overtly obey Condition A): those that are strong, and those that are weak. We also summarize Ahn’s account of this distinction, which will serve as the starting point for our analysis of LBEs. In Sect. 3.1.2, we motivate a proposal that incorporates Ahn’s insights with the general competition principle of Cardinaletti and Starke (1999). As we will show, this combination of ingredients allows us to account for LBEs in English without restricting Condition A or appealing to homophony.

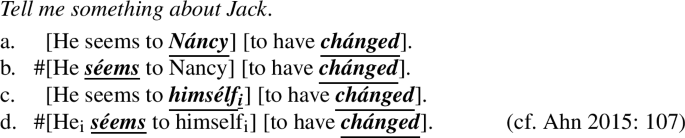

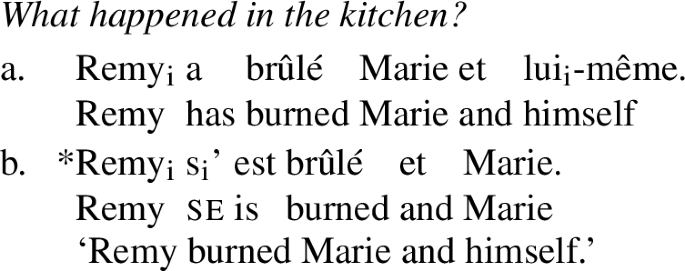

3.1.1 Two types of plain anaphors in English

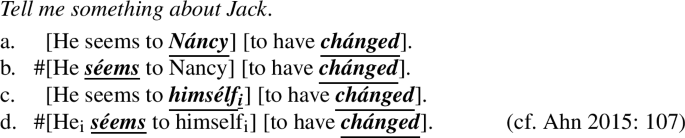

3.1.1.1 Ahn’s (2015) empirical discovery

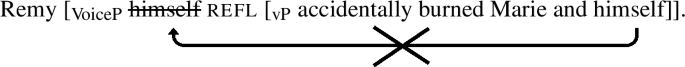

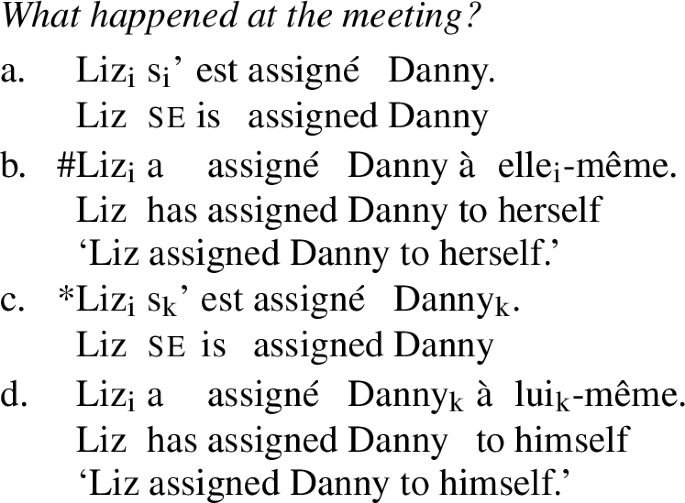

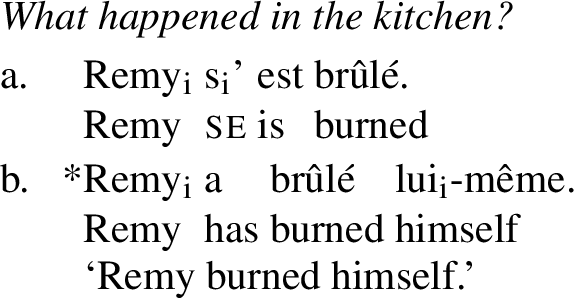

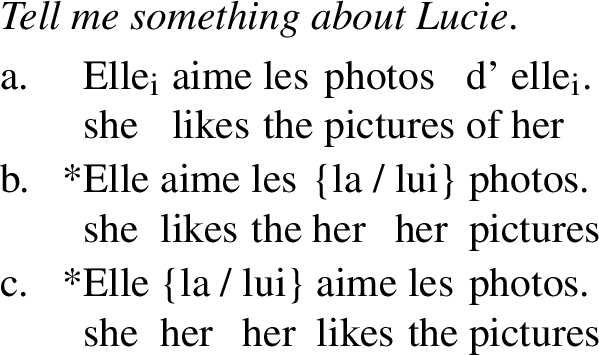

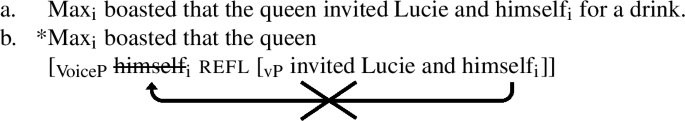

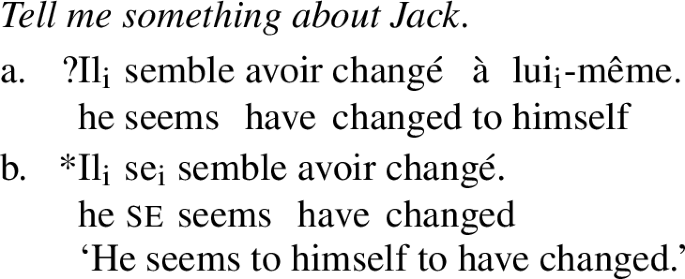

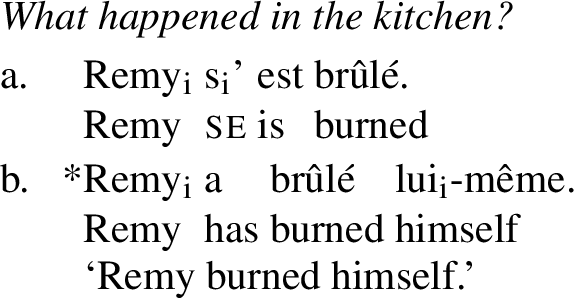

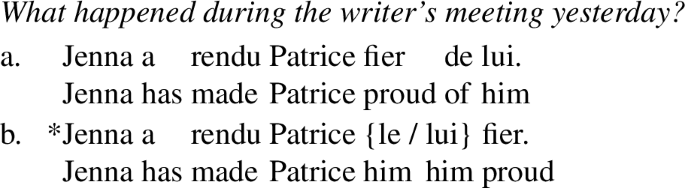

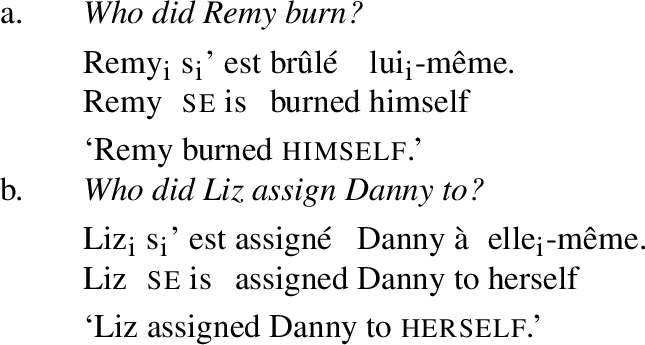

To understand why logophoric binding is blocked in examples like (67b), we will reexamine the behavior of anaphors through a different lens than Condition A, namely prosody, as done in Ahn (2015) (cf. Spathas 2010: Chap. 3Footnote 34). Specifically, Ahn (2015) observes that English plain reflexives descriptively fall into two classes: those that exhibit exceptional prosodic behaviors, and those that do not. To test the prosodic behavior of reflexives, Ahn examines them in positions where other elements bear nuclear phrasal stress in maximally broad-focus contexts (i.e. contexts in which they are neither given nor contrastively focused), as illustrated in (70)–(72).Footnote 35

-

(70)

What happened in the kitchen?

-

a.

Remy accidentally burned Maríe.

-

b.

#Remyi accidentally búrned Marie. (Ahn 2015: 42)

-

a.

-

(71)

What happened in the kitchen?

-

a.

#Remyi accidentally burned himsélfi.

-

b.

Remyi accidentally búrned himselfi. (Ahn 2015: 42)

-

a.

-

(72)

What happened in the kitchen?

-

a.

Remyi accidentally burned Marie and himsélfi.

-

b.

# Remyi accidentally burned Maríe and himselfi. (cf. Ahn 2015: 62)

-

a.

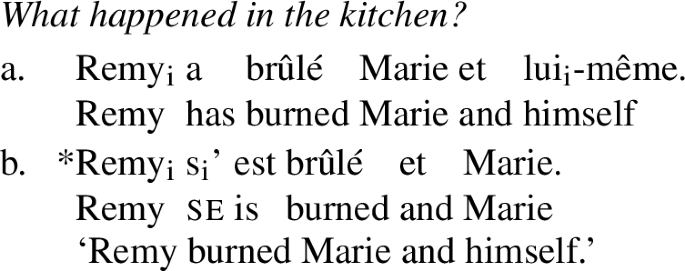

On the basis of anaphora-independent data, Ahn (2015) demonstrates that, in neutral contexts, English phrasal stress is received by the most deeply embedded constituent in a spellout domain.Footnote 36 Whereas nuclear stress therefore typically falls on the direct object in basic transitive sentences (e.g., on Marie in (70)), it may not fall on himself in (71), or else the sentence is rendered infelicitous. Ahn calls anaphors that exhibit such exceptional prosodic behavior extrametrical; we will refer to them as weak. Importantly, not all anaphors are weak, as illustrated in (72), in which conjoined himself bears nuclear stress; such reflexives are strong, patterning with referential DPs. This immediately excludes the null hypothesis that reflexives never bear phrasal stress because they are given as a result of necessitating an antecedent.

Here we can already notice a link between prosodic behavior and logophoric behavior: the configurations that license logophoric binding in English (e.g. (67a)) resemble the configurations that exclude weak anaphors (e.g. (72)); conversely, the configurations that exclude logophoric binding (e.g. (67b)) resemble the configurations that can host weak anaphors (e.g. (71)). Ahn (2015) does not discuss logophoric anaphors and, in fact, leads to wrong predictions about them. We will nevertheless see that Ahn’s proposal provides the crucial clue to derive LBEs in English: logophorically bound anaphors cannot be weak.

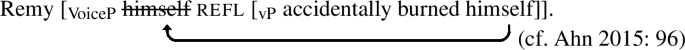

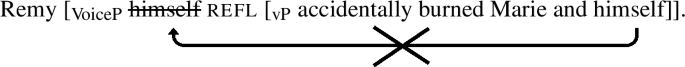

3.1.1.2 Ahn’s (2015) account: Movement to reflexive Voice

This section offers an overview of Ahn’s (2015) account of the prosodic facts introduced above. While we will ultimately depart from certain details of Ahn’s proposal, two aspects will carry over to the present proposal: the appeal to movement, and the appeal to a covert reflexivizing head distinct from the anaphor.

As a first step to analyze the contrast between (71) and (72), Ahn (2015) identifies three syntactic configurations in which anaphors are strong.Footnote 37 First, English anaphors bear stress when they are separated from their antecedent by an island boundary. This was the case for himself in (72), which occurs in a coordinated structure; this is also the case for himself in (73), which appears in another type of island.

-

(73)

What is the setup for the show?

-

a.

Louis plays a character like his bróther.

-

b.

# Louis plays a character líke his brother.

-

c.

Louisi plays a character like himsélfi.

-

d.

# Louisi plays a character líke himselfi. (Ahn 2015: 50)

-

a.

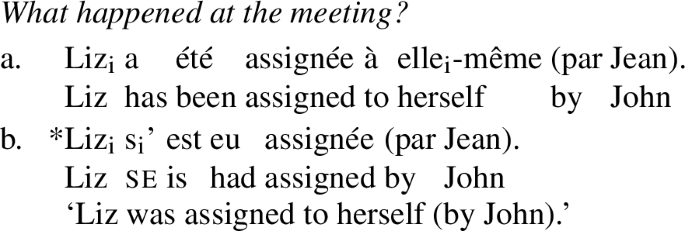

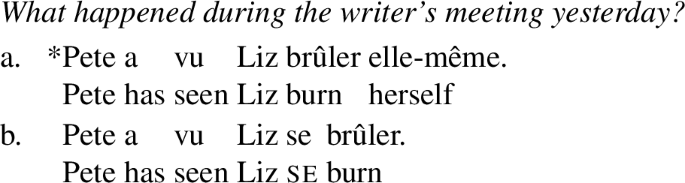

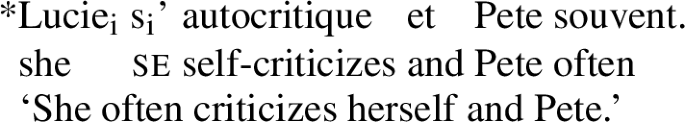

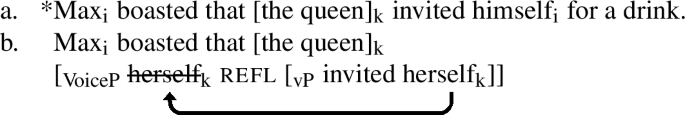

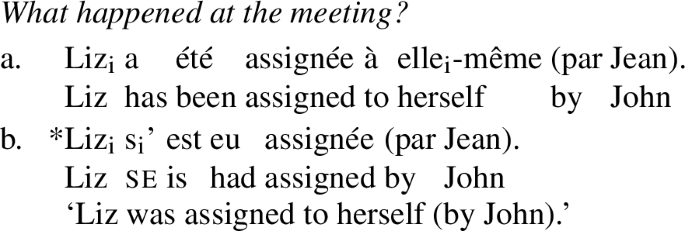

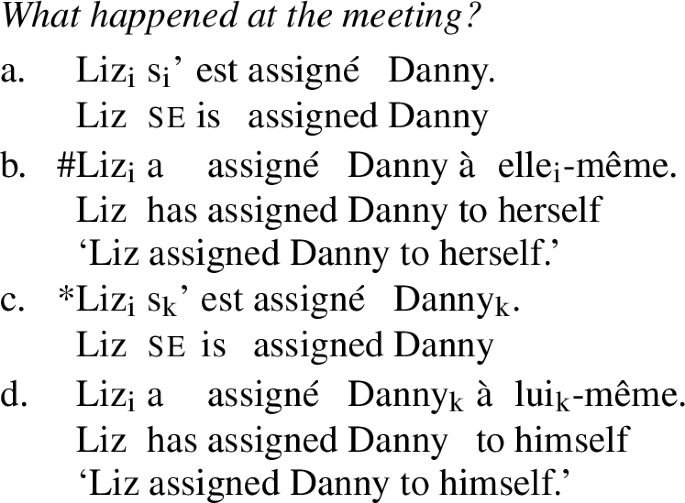

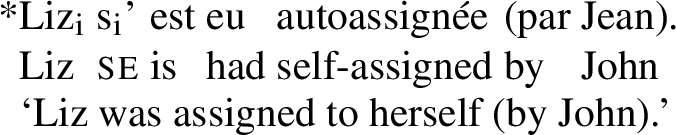

Second, English anaphors bear stress when their antecedents are derived subjects. This includes both subjects of passives as in (74) and subjects of raising verbs as in (75).

-

(74)

What happened at the meeting?

-

a.

Lizi was accidentally assigned to hersélfi.

-

b.

#?Lizi was accidentally assígned to herselfi. (cf. Ahn 2015: 53, 106)

-

a.

-

(75)

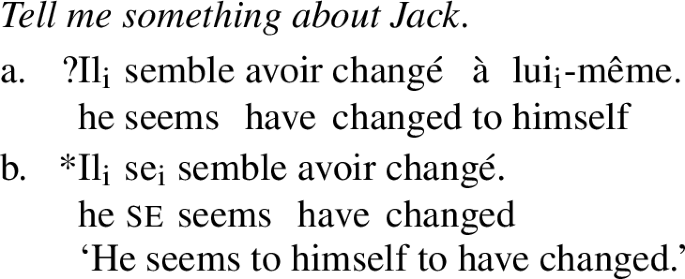

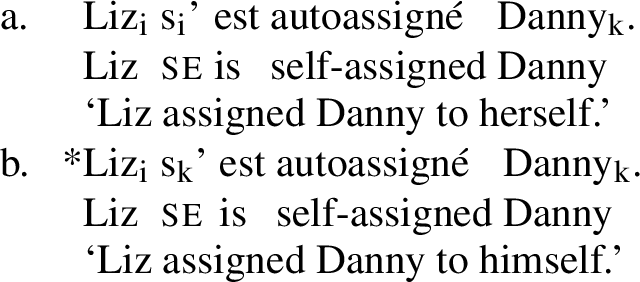

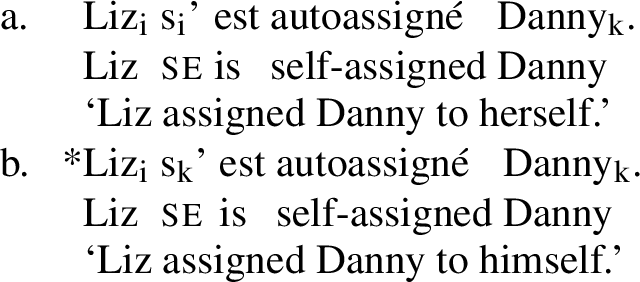

Third, English anaphors are strong if their antecedent is not the subject, as shown in (76c–76d) vs. (76a–76b). Note that prosody thereby distinguishes subject-bound reflexives from other instances of coargument-bound reflexives, further supporting our conclusion that coargumenthood per se does not determine an empirically correct dividing line for English anaphors.

-

(76)

What happened at the meeting?

-

a.

# Lizi assigned Danny to hersélfi.

-

b.

Lizi assigned Dánny to herselfi.

-

c.

Lizi assigned Dannyk to himsélfk.

-

d.

# Lizi assigned Dánnyk to himselfk. (cf. Ahn 2015: 52, 63)

-

a.

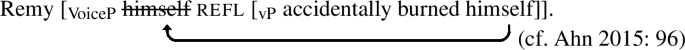

To account for these findings, Ahn (2015) is inspired by the similar behavior of the French reflexive clitic se and Sportiche’s (2014) analysis of it (as will become clearer in Sect. 3.1.2.1). Specifically, Ahn posits the presence of a reflexive Voice head (refl), which is endowed with an EPP feature that obligatorily attracts a reflexive argument. In a sentence like (71b), himself undergoes “covert overt” movementFootnote 38 to the specifier of the refl, as shown in the simplified representation in (77), thus mimicking reflexive clitic movement.

-

(77)

Ahn’s appeal to movement directly derives the prosodic weakness of himself in sentences like (71b): because himself undergoes movement to the specifier of VoiceP, it is not the most deeply embedded constituent in its spellout domain and, hence, does not bear nuclear stress.

Movement also derives the fact that weak reflexives cannot be separated from their antecedent by an island boundary, as seen in (72)–(73): because himself occurs in an island, it cannot move to VoiceP, as shown below in the simplified representation of (72).

-

(78)

As we will detail in Sect. 3.1.1.3, Ahn assumes in such cases (i.e. when the presence of a reflexive Voice yields ungrammaticality) that reflexives can be licensed in a derivation without reflexive Voice. In the absence of a reflexive Voice, himself in (72)–(73) remains the most deeply embedded constituent of its spellout domain, leaving it the target for nuclear stress.