Abstract

Sorption isotherms describe the relation between the equilibrium moisture content of a material and the ambient relative humidity. Most materials exhibits sorption hysteresis, that is, desorption give higher equilibrium moisture contents than absorption at equal ambient climate conditions. Sorption hysteresis is commonly evaluated by determination of an absorption isotherm followed by desorption starting from the highest relative humidity used in the absorption measurement (typically 95%). The latter is often interpreted as the desorption isotherm but is in fact a scanning isotherm, i.e. an isotherm obtained from neither dry nor water-saturated state. In the present study, we investigated the difference between desorption isotherms and scanning isotherms determined by desorption from different high relative humidity levels reached by absorption and how this difference influenced the evaluation of sorption hysteresis. The measurements were performed on Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst.) using automated sorption balances. Hysteresis evaluated from desorption isotherms gave linear absolute sorption hysteresis for the studied relative humidity range (0–96%), whereas hysteresis evaluated from scanning isotherms gave non-linear curves with a peak between 50 and 80% relative humidity. The position of this peak depended on the relative humidity from which desorption was initiated. Consequently, understanding and evaluation of sorption hysteresis might be challenging if scanning isotherms are used instead of desorption isotherms, hereby increasing the risk of misinterpreting the results.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water influences most physical wood properties such as mechanical properties and dimensional stability, and additionally plays an important role in wood degradation processes. The interaction between wood and water has therefore been widely studied, and this is often done by measuring sorption isotherms. These depict the equilibrium moisture content of a material as a function of ambient relative humidity (RH) at constant temperature. Typically, the path to equilibrium, i.e. whether equilibrium is obtained through an increase (absorption) or a decrease (desorption) in moisture content, influences the moisture content at given climatic conditions; desorption to equilibrium results in a higher moisture content than absorption to equilibrium with the same ambient climate conditions (Masson and Richards 1906). This phenomenon is termed sorption hysteresis and can be observed in many chemically and structurally different materials, e.g. polymers (Watt 1980), cement based materials (Espinosa and Franke 2006a), food (Wolf et al. 1972) and wood (Pidgeon and Maass 1930). Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain sorption hysteresis such as the ink-bottle or pore-blocking effect (McBain 1935), differences between absorption and desorption in principal radius of condensation (Cohan 1938), or free volume in swelling polymeric materials (Vrentas and Vrentas 1996). Sorption isotherms initiated from non-extreme conditions (neither dry nor saturated state) are generally referred to as scanning isotherms (Espinosa and Franke 2006a, b; Peralta and Bangi 1998; Velasco et al. 2016). Scanning isotherms connect the desorption and absorption isotherms and describe the moisture content of a material when it is exposed to alternate absorption and desorption.

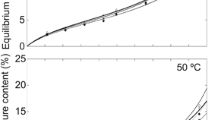

Wood can take up water both in the polymeric cell walls and in the macrovoid structure (pits, lumina etc.), and it exhibits sorption hysteresis in the entire RH-range, see Fig. 1. The RH-range from 0% up to 97–98% is commonly referred to as “hygroscopic” and the range above as “over-hygroscopic”. The exact intersection between these two ranges is not well-defined (Espinosa and Franke 2006a), but for wood the differentiation reflects a change in the way water is taken up. In wood, water is predominantly found as bound water in cell walls in the hygroscopic range, whereas the over-hygroscopic range is dominated by capillary condensation of liquid water in the macrovoid structure (e.g. lumina and pits). Hence, the suggested mechanisms behind sorption hysteresis in wood are different in the two moisture ranges. In the over-hygroscopic range, the main suggested mechanism is the ink-bottle effect (Fortin 1979; Salin 2008) where pits act as bottlenecks to the cell lumina. In the hygroscopic range, sorption hysteresis is related to internal changes in cell walls as the amount of liquid water in the void structure is minuscule. Based on the conceptual framework of Vrentas and Vrentas (1996), it has been suggested that sorption hysteresis is related to the mechanics of shrinkage and swelling of the cellulosic cell walls during changes in moisture content (Engelund et al. 2013; Hill et al. 2009, 2012a, b). The exact mechanism is not fully understood, but an important aspect is assumed to be the glass transition (softening) of constituent cell wall polymers (Engelund et al. 2013; Keating et al. 2013; Salmén and Larsson 2018).

Sorption isotherms for Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst.) as a function of pore water pressure based on data from Fredriksson and Johansson (2016). The insert show a magnification of the hygroscopic part as a function of RH on a linear x-axis, i.e. as sorption isotherms are most commonly presented in literature. Note that the tranformation from relative humidity to pressure is made based on the Kelvin equation which is not necessarily valid in the whole hygroscopic range (Sing et al. 2014)

Sorption hysteresis in wood and cellulosic fibres is commonly evaluated by determination of the absorption isotherm after initially drying the material, followed by determination of an isotherm in desorption starting from the highest RH used in the absorption measurement (Ammer 1963; Higgins 1957; Jeffries 1960a; Kelsey 1957; Peralta 1995; Pidgeon and Maass 1930; Seifert 1972; Sheppard and Newsome 1929; Urquhart and Eckersall 1930; Wahba and Nashed 1957; Wangaard and Granados 1967; Weichert 1963). In recent years, when the use of automated sorption balances has become more wide-spread, the high RH from which desorption is initiated is typically between 90 and 96% (Ceylan et al. 2014, 2012; Cordin et al. 2017; Hill et al. 2009, 2012b; Himmel and Mai 2015; Hosseinpourpia et al. 2016; Jalaludin et al. 2010; Kymäläinen et al. 2015; Okubayashi et al. 2005a, b; Popescu et al. 2014; Popescu and Hill 2013; Shi and Avramidis 2017; Simón et al. 2017; Xie et al. 2011). However, using this measurement procedure, it is not hysteresis between desorption and absorption isotherms that is evaluated, but hysteresis between a scanning isotherm and the absorption isotherm. This difference is important to consider when interpreting a phenomenon like sorption hysteresis. In this study, we show how the use of scanning isotherms instead of desorption isotherms for characterising sorption hysteresis yields complex results which may lead to misinterpretations of the mechanisms behind sorption hysteresis.

Materials and methods

Material

Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst.) from an experimental forest in Southern Sweden was used, see Fredriksson et al. (2016) for further information. Samples of earlywood tissue from mature sapwood were cut and vacuum saturated with deionised water using the following procedure: The samples were subjected to vacuum (1–2 mbar) in a glass desiccator for 1 h, deionized water was then added while running the vacuum pump (20 mbar), and finally atmospheric pressure was re-established. Specimens corresponding to a dry mass of 3–6 mg were then cut using a razor blade. In addition, some measurements were performed on specimens of latewood from mature sapwood and on early- and latewood specimens from mature heartwood, see Supplementary Information (SI). Before the specimens were placed in the sorption balance, each piece was wiped with a moist cloth to remove excess surface water.

Sorption measurements and hysteresis evaluation

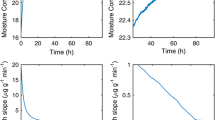

Sorption isotherms were measured at 20 °C using automated sorption balances (DVS Advantage, Surface Measurement Systems Ltd., London) which monitor the mass of a specimen (balance resolution 0.1 µg) while the RH is incrementally changed in pre-programmed steps, see e.g. Williams (1995). The time necessary to reach equilibrium at each RH level is specified either as a fixed period of time or by a mass stability (dm/dt) criterion where the mass change in a given time window is below a threshold value defined by the user. Specific levels of RH are generated by mixing dry and water-saturated streams of nitrogen gas. Here, the accuracy of generated RH was validated using the method described by Wadsö et al. (2009). All measurements started with water-saturated specimens.

Experiment 1

Desorption isotherms were determined by conditioning water-saturated specimens to the following RH levels: 97-95-90-85-80-70-60-50-40-20-10-5-0%. Subsequently, absorption isotherms were determined by increasing the RH to 97% followed by a scanning desorption isotherm from 97% RH, both using the same RH levels as for the initial desorption. These measurements were part of the study reported by Fredriksson and Thygesen (2017) and used a dm/dt criterion of 0.001% min−1 over 10 min for defining equilibrium at each step. It should be noted that the dm/dt in the sorption balance used is calculated based on a reference mass. If the measurements starts with absorption, this reference mass is generally the dry mass. However, since desorption isotherms were determined in the present study, the reference sample mass was the mass after the first step at 97% RH. The same experimental protocol was also used on latewood specimens from mature sapwood and early- and latewood specimens from mature heartwood, see SI.

Experiment 2

Four additional desorption isotherms were determined after conditioning water-saturated specimens to the following RH levels: 95-80-65-50-35-0%. For two specimens, the absorption isotherms up to 95% RH were then determined followed by a scanning desorption isotherm from 95% RH, both using the same RH levels as for desorption. For two other specimens, the absorption isotherms were determined up to 80% RH before scanning desorption was initiated. Also here, the same RH levels were used. Due to uncertainties related to the use of dm/dt-criteria (Glass et al. 2018, 2017) and the fact that starting with desorption makes the reference mass used to calculate dm/dt more uncertain, fixed periods of time at each RH level were used: 60 h at 95% RH, 24 h at 80% RH and 0% RH, and 12 h at all other RH levels. For all measurements, the specimen was finally dried for 8 h by using the pre-heater to locally increase the temperature while purging with dry nitrogen gas. The temperature was slowly ramped to 60 °C over 1 h and kept constant at this level for 6 h before it was slowly ramped to 20 °C over 1 h. Finally, this drying protocol was followed by a 2 h thermal stabilisation period at 20 °C before the dry mass was taken. The equilibrium moisture content at each RH level was evaluated as mass of water divided by the dry mass of the specimen.

After the measurements had been performed, the dm/dt criteria based on dry mass were calculated for all RH steps in order to estimate the error in moisture content. In absorption, all steps had in the end a dm/dt of less than 3 µg g−1 min−1 with a 2 h regression window, meaning that the moisture contents reported for absorption is less than 0.004 kg kg−1 lower than the true equilibrium value, based upon the errors indicated by Glass et al. (2018). The exception was the absorption step to 95% RH which had a dm/dt of around 6 µg g−1 min−1 with a 2 h regression window which gives an error in moisture content within the range 0.004–0.008 kg kg−1. In desorption, all steps had in the end a dm/dt on average in the range 3–4 µg g−1 min−1 with a 2 h regression window, which indicates that the reported moisture contents are around 0.002–0.008 kg kg−1 higher than the true equilibrium value. Given that the moisture content error for a given dm/dt increases with increasing RH, the calculated absolute sorption hysteresis is estimated to be up to 0.004 kg kg−1 too high at 35% RH and up to 0.012 kg kg−1 too high at 95% RH.

Sorption hysteresis was evaluated between absorption and desorption isotherms as well as between absorption and scanning isotherms. The evaluation was made both as absolute difference in moisture content at each RH level and as relative difference. The latter was determined by dividing the absolute moisture content difference by the absorption equilibrium moisture content at each RH level. For the measurements performed using a dm/dt criterion, the moisture content at 97% RH was not included when evaluating hysteresis due to a lack of equilibrium.

Results and discussion

Sorption isotherms

Figure 2a, b shows the sorption isotherms determined in desorption, absorption, and scanning for Norway spruce earlywood. All isotherms and additional data for other tissue types can be found in SI. As expected, desorption initiated from a non-saturated state reached by absorption gave a lower sorption isotherm than if initiated from the water-saturated state; isotherms initiated from 95 to 97% RH and 80% RH did not merge with the desorption isotherm until around 50–60% RH and 50% RH, respectively. This has also previously been shown by Hoffmeyer et al. (2011); here the scanning isotherm of Norway spruce initiated from a high RH merged with the desorption isotherm around 70% RH. If the hygroscopic desorption isotherm is placed in the context of the full desorption isotherm (Fig. 1), it is clearly seen that due to the large sorption hysteresis, the initial moisture content needs to be substantially higher than the equilibrium moisture content at 95% RH reached by absorption for the specimen to follow the desorption isotherm. Consequently, starting desorption from a high hygroscopic RH reached by absorption, yields scanning isotherms, and the moisture content in the upper part of the hygroscopic range is underestimated if these scanning isotherms are interpreted as actual desorption isotherms. In addition, water-saturation is necessary in order to re-open the cell wall structure in Norway spruce after drying and make all hydrophilic functional groups accessible for water (Thybring et al. 2017). Thus, initiating desorption from less than water-saturation might not provide sorption data representative of the actual desorption isotherm at any RH level due to insufficient re-opening of the cell wall structure.

Sorption isotherms for Norway spruce earlywood: a Experiment 1: desorption (upper solid line), absorption (lower solid line), and scanning from 97% RH (dashed line). b Experiment 2: average desorption isotherm (upper solid line), average absorption isotherm (lower solid line), and average scanning isotherms from 95% RH (dashed line) and 80% RH (dotted line). c, d absolute sorption hysteresis, and e, f relative sorption hysteresis calculated from the sorption isotherms in a and b

Sorption hysteresis

Figure 2c–f show absolute and relative sorption hysteresis, respectively, evaluated from the sorption isotherm data presented in Fig. 2a, b. The sorption hysteresis calculated from desorption isotherms was markedly different than sorption hysteresis calculated from scanning isotherms. While desorption isotherms in the hygroscopic range gave a linear absolute sorption hysteresis and fairly constant relative sorption hysteresis, the same quantities were complex, non-linear curves when calculated based on scanning isotherms. The latter had a peak in absolute hysteresis around 75% RH when desorption was initiated from 95% RH, but the position of this peak depended on the RH from which the scanning isotherm was initiated (Fig. 2d). That the hysteresis pattern depends on the RH from which desorption is initiated, has also previously been observed by Peralta (1995) who evaluated the ratio between the absorption isotherm and isotherms determined in desorption initiated from different RH levels.

In literature, desorption is most often initiated from 95% RH and a peak in absolute hysteresis is observed around 75% RH (Cordin et al. 2017; Hill et al. 2009, 2012b; Himmel and Mai 2015; Hosseinpourpia et al. 2016; Jalaludin et al. 2010; Kymäläinen et al. 2015; Okubayashi et al. 2005a, b; Popescu et al. 2014; Popescu and Hill 2013; Shi and Avramidis 2017; Simón et al. 2017; Vahtikari et al. 2017; Xie et al. 2011) in accordance with the present study. This is also clear from Fig. 3, where average absolute sorption hysteresis from the present study (Fig. 2c, d) is compared to sorption hysteresis evaluated from literature data for spruce. Here, it is also seen that the absolute sorption hysteresis is generally higher for the literature data and data from Experiment 1 than for data from Experiment 2. This is most probably due to that tougher equilibrium criteria were used in Experiment 2.

Absolute sorption hysteresis for Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst.) from literature (grey intervals) and data from Fig. 2c, d (black lines). The absolute sorption hysteresis from literature data was evaluated from absorption and desorption isotherms from water saturated state (Ahlgren 1972; Fredriksson and Johansson 2016), between absorption and desorption from 94 to 95% RH (Gilani and Schwarze 2015; Gilani et al. 2014; Kymäläinen et al. 2015; Zillig 2009) and between absorption and desorption from 80% RH (Zillig 2009)

Evaluating sorption hysteresis based on scanning isotherms is not necessarily less correct than by use of desorption isotherms. However, it is important to consider how the sorption isotherms were determined when interpreting the hysteresis curves. The currently favoured theory for sorption hysteresis in polymeric materials (Hill and Beck 2017; Hill et al. 2009, 2012a, b; Vrentas and Vrentas 1996) explains the phenomenon as a result of hysteresis in volumetric swelling due to kinetic retardation during shrinkage/swelling. According to this theory, sorption hysteresis is expected to decrease with increasing temperature and only be seen when the constituent polymers are below their softening point. Several studies on water sorption in various cellulosic materials have shown a decrease in hysteresis with increasing temperature (Hill et al. 2009, 2010; Jeffries 1960b; Kelsey 1957; Salmén and Larsson 2018; Weichert 1963) which supports this theory. However, a few studies on wood report insignificant changes in relative hysteresis between 35 and 50 °C (Esteban et al. 2008a, b, 2009). For wood, the cell wall polymers that undergo softening at normal temperature are the hemicelluloses. This occurs around 65–75% RH at room temperature (Engelund et al. 2013; Irvine 1984; Kelley et al. 1987; Olsson and Salmén 2004). For instance, Keating et al. (2013) reported sorption hysteresis to vanish in man-made hemicellulose (galactomannan) films above 75% RH at 25 °C, and this RH level corresponded with the softening point characterised by dynamic mechanical analysis. It can therefore be tempting to associate the decrease in hysteresis for wood above 75% RH, as observed in several studies when desorption was initiated from 90 to 95% RH, with softening of the hemicelluloses. However, as clearly seen in Fig. 2d, the peak in sorption hysteresis for wood is a result of scanning isotherms being used to calculate hysteresis, and the peak position changes with the RH from which desorption is initiated. Whether this is also the case for other biopolymeric materials remains to be investigated.

Conclusions

Determination of desorption isotherms require that the measurements starts at water-saturation. Desorption from an initial moisture content reached by absorption at high RH will generate a scanning isotherm. Evaluating sorption hysteresis for Norway spruce wood based on scanning isotherms instead of desorption isotherms, gave a non-linear behaviour and a peak in hysteresis, which depended on the RH from which desorption was initiated. No peak in hysteresis was however seen in the studied RH range (0–96%) when the sorption hysteresis evaluation was based on desorption isotherms, i.e. sorption isotherms initiated from water-saturation. Consequently, understanding and evaluating the mechanisms behind sorption hysteresis is further challenged if scanning isotherms are used instead of desorption isotherms, hereby increasing the risk of misinterpreting the results.

References

Ahlgren L (1972) Fuktfixering i porösa byggnadsmaterial (Moisture fixation in porous building materials). Dissertation, Lund University

Ammer U (1963) Untersuchungen über die Sorption pilzbefallenen Holzes. Holz als Roh-und Werkstoff 21:465–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02608818

Ceylan Ö, Van Landuyt L, Meulewaeter F, De Clerck K (2012) Moisture sorption in developing cotton fibers. Cellulose 19:1517–1526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-012-9737-x

Ceylan Ö, Goubet F, De Clerck K (2014) Dynamic moisture sorption behavior of cotton fibers with natural brown pigments. Cellulose 21:1149–1161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-014-0206-6

Cohan LH (1938) Sorption hysteresis and the vapor pressure of concave surfaces. J Am Chem Soc 60:433–435. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja01269a058

Cordin M, Griesser UJ, Bechtold T (2017) Analysis of moisture sorption in lyocell-polypropylene composites. Cellulose 24:1837–1847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-017-1227-8

Engelund ET, Thygesen LG, Svensson S, Hill CAS (2013) A critical discussion of the physics of wood-water interactions. Wood Sci Technol 47:141–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00226-012-0514-7

Espinosa RM, Franke L (2006a) Influence of the age and drying process on pore structure and sorption isotherms of hardened cement paste. Cem Concr Res 36:1969–1984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2006.06.010

Espinosa RM, Franke L (2006b) Inkbottle pore-method: prediction of hygroscopic water content in hardened cement paste at variable climatic conditions. Cem Concr Res 36:1954–1968. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2006.06.011

Esteban LG, de Palacios P, Fernández FG, Guindeo A, Cano NN (2008a) Sorption and thermodynamic properties of old and new Pinus sylvestris wood. Wood Fiber Sci 40:111–121

Esteban LG, de Palacios P, Fernandez FG, Guindeo A, Conde M, Baonza V (2008b) Sorption and thermodynamic properties of juvenile Pinus sylvestris L. wood after 103 years of submersion. Holzforschung 62:745–751. https://doi.org/10.1515/hf.2008.106

Esteban LG, de Palacios P, Fernandez FG, Martin JA, Genova M, Fernandez-Golfin JI (2009) Sorption and thermodynamic properties of buried juvenile Pinus sylvestris L. wood aged 1,170 ± A 40 BP. Wood Sci Technol 43:679–690. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00226-009-0261-6

Fortin Y (1979) Moisture content—matric potential relationship and water flow properties of wood at high moisture contents. Dissertation, University of British Columbia

Fredriksson M, Johansson P (2016) A method for determination of absorption isotherms at high relative humidity levels: measurements on lime-silica brick and Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst.). Dry Technol 34:132–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/07373937.2015.1041035

Fredriksson M, Thygesen LG (2017) The states of water in Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst.) studied by low-field nuclear magnetic resonance (LFNMR) relaxometry: assignment of free-water populations based on quantitative wood anatomy. Holzforschung 71:77–90. https://doi.org/10.1515/hf-2016-0044

Fredriksson M, Wadsö L, Johansson P, Ulvcrona T (2016) Microclimate and moisture content profile measurements in rain exposed Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst.) joints. Wood Mater Sci Eng 11:189–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/17480272.2014.965742

Gilani MS, Schwarze FWMR (2015) Hygric properties of Norway spruce and sycamore after incubation with two white rot fungi. Holzforschung 69:77. https://doi.org/10.1515/hf-2013-0247

Gilani MS, Tingaut P, Heeb M, Schwarze FWMR (2014) Influence of moisture on the vibro-mechanical properties of bio-engineered wood. J Mater Sci 49:7679–7687. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-014-8476-9

Glass SV, Boardman CR, Zelinka SL (2017) Short hold times in dynamic vapor sorption measurements mischaracterize the equilibrium moisture content of wood. Wood Sci Technol 51:243–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00226-016-0883-4

Glass SV, Boardman CR, Thybring EE, Zelinka SL (2018) Quantifying and reducing errors in equilibrium moisture content measurements with dynamic vapor sorption (DVS) experiments. Wood Sci Technol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00226-018-1007-0

Higgins NC (1957) The equilibrium moisture content-relative humidity relationships of selected native and foreign woods. 7:371–377

Hill C, Beck G (2017) On the applicability of the Flory–Huggins and Vrentas models for describing the sorption isotherms of wood. Int Wood Prod J 8:50–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/20426445.2016.1275094

Hill CAS, Norton A, Newman G (2009) The water vapor sorption behavior of natural fibres. J Appl Polym Sci 112:1524–1537. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.29725

Hill CAS, Norton AJ, Newman G (2010) The water vapour sorption properties of Sitka spruce determined using a dynamic vapour sorption apparatus. Wood Sci Technol 44:497–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00226-010-0305-y

Hill CAS, Keating BA, Jalaludin Z, Mahrdt E (2012a) A rheological description of the water vapour sorption kinetics behaviour of wood invoking a model using a canonical assembly of Kelvin–Voigt elements and a possible link with sorption hysteresis. Holzforschung 66:35–47. https://doi.org/10.1515/HF.2011.115

Hill CAS, Ramsay J, Keating B, Laine K, Rautkari L, Hughes M, Constant B (2012b) The water vapour sorption properties of thermally modified and densified wood. J Mater Sci 47:3191–3197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-011-6154-8

Himmel S, Mai C (2015) Effects of acetylation and formalization on the dynamic water vapor sorption behavior of wood. Holzforschung 69:633. https://doi.org/10.1515/hf-2014-0161

Hoffmeyer P, Engelund ET, Thygesen LG (2011) Equilibrium moisture content (EMC) in Norway spruce during the first and second desorptions. Holzforschung 65:875–882. https://doi.org/10.1515/HF.2011.112

Hosseinpourpia R, Adamopoulos S, Mai C (2016) Dynamic vapour sorption of wood and holocellulose modified with thermosetting resins. Wood Sci Technol 50:165–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00226-015-0765-1

Irvine GM (1984) The glass transitions of lignin and hemicellulose and their measurement by differential thermal-analysis. Tappi J 67:118–121

Jalaludin Z, Hill CAS, Xie Y, Samsi HW, Husain H, Awang K, Curling SF (2010) Analysis of the water vapour sorption isotherms of thermally modified acacia and sesendok. Wood Mater Sci Eng 5:194–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/17480272.2010.503940

Jeffries R (1960a) Part I. The sorption of water by celluloses below 100 °C. J Text Inst 51:T340–T374. https://doi.org/10.1080/19447026008659778

Jeffries R (1960b) Sorption of water by cellulose and eight other textile polymers. Part II. The sorption of water vapour below 100°C by textile polymers other than cellulose. J Text Inst 51:T399–T418. https://doi.org/10.1080/19447026008659782

Keating BA, Hill CAS, Sun D, English R, Davies P, McCue C (2013) The water vapor sorption behavior of a galactomannan cellulose nanocomposite film analyzed using parallel exponential kinetics and the Kelvin–Voigt viscoelastic model. J Appl Polym Sci 129:2352–2359. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.39132

Kelley SS, Rials TG, Glasser WG (1987) Relaxation behavior of the amorphous components of wood. J Mater Sci Lett 22:617–624. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01160778

Kelsey KE (1957) The sorption of water vapour by wood. Aust J Appl Sci 8:42–54

Kymäläinen M, Rautkari L, Hill CAS (2015) Sorption behaviour of torrefied wood and charcoal determined by dynamic vapour sorption. J Mater Sci 50:7673–7680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-015-9332-2

Masson O, Richards ES (1906) On the hygroscopic action of cotton. Proc R Soc Lond Ser A 78:412–429

McBain JW (1935) An explanation of hysteresis in the hydration and dehydration of gels. J Am Chem Soc 57:699–700. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja01307a502

Okubayashi S, Griesser UJ, Bechtold T (2005a) Moisture sorption/desorption behavior of various manmade cellulosic fibers. J Appl Poly Sci 97:1621–1625. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.21871

Okubayashi S, Griesser UJ, Bechtold T (2005b) Water accessibilities of man-made cellulosic fibers–effects of fiber characteristics. Cellulose 12:403–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-005-2179-y

Olsson AM, Salmén L (2004) The softening behavior of hemicelluloses related to moisture. ACS Symp Ser 864:184–197. https://doi.org/10.1021/bk-2004-0864.ch013

Peralta PN (1995) Sorption of moisture by wood within a limited range of relative humidities. Wood Fiber Sci 27:13–21

Peralta PN, Bangi AP (1998) Modeling wood moisture sorption hysteresis based on similarity hypothesis. Part 1. Direct approach. Wood Fiber Sci 30:48–55

Pidgeon LM, Maass O (1930) The adsorption of water by wood. J Am Chem Soc 52:1053–1069. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja01366a033

Popescu CM, Hill CAS (2013) The water vapour adsorption–desorption behaviour of naturally aged Tilia cordata Mill. wood. Polym Degrad Stabil 98:1804–1813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2013.05.021

Popescu C-M, Hill CAS, Curling S, Ormondroyd G, Xie Y (2014) The water vapour sorption behaviour of acetylated birch wood: how acetylation affects the sorption isotherm and accessible hydroxyl content. J Mater Sci 49:2362–2371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-013-7937-x

Salin J-G (2008) Drying of liquid water in wood as influenced by the capillary fiber network. Dry Technol 26:560–567. https://doi.org/10.1080/07373930801944747

Salmén L, Larsson PA (2018) On the origin of sorption hysteresis in cellulosic materials. Carbohydr Polym 182:15–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.11.005

Seifert J (1972) On the sorption and swelling of wood and wood base materials—Part 1: influences on the sorption of wood base materials. Holz Roh Werkst 30:99–111

Sheppard SE, Newsome PT (1929) The sorption of water vapor by cellulose and its derivatives. J Phys Chem 33:1817–1835

Shi J, Avramidis S (2017) Water sorption hysteresis in wood: I review and experimental patterns—geometric characteristics of scanning curves. Holzforschung 71:307–316. https://doi.org/10.1515/hf-2016-0120

Simón C, Esteban LG, Palacios Pd, Fernández FG, García-Iruela A (2017) Sorption/desorption hysteresis revisited. Sorption properties of Pinus pinea L. analysed by the parallel exponential kinetics and Kelvin–Voigt models. Holzforschung 71:171. https://doi.org/10.1515/hf-2016-0097

Sing KSW, Rouquerol F, Rouquerol J, Llewellyn P (2014) 8—Assessment of mesoporosity. In: Adsorption by powders and porous solids, 2nd edn. Academic Press, Oxford, pp 269–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097035-6.00008-5

Thybring EE, Thygesen LG, Burgert I (2017) Hydroxyl accessibility in wood cell walls as affected by drying and re-wetting procedures. Cellulose 24:2375–2384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-017-1278-x

Urquhart AR, Eckersall N (1930) The moisture relations of cotton: VII. A study of hysteresis. J Text Inst 21:T499–T510

Vahtikari K, Rautkari L, Noponen T, Lillqvist K, Hughes M (2017) The influence of extractives on the sorption characteristics of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.). J Mater Sci 52:10840–10852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-017-1278-0

Velasco LF, Guillet-Nicolas R, Dobos G, Thommes M, Lodewyckx P (2016) Towards a better understanding of water adsorption hysteresis in activated carbons by scanning isotherms. Carbon 96:753–758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2015.10.017

Vrentas JS, Vrentas CM (1996) Hysteresis effects for sorption in glassy polymers. Macromolecules 29:4391–4396. https://doi.org/10.1021/ma950969l

Wadsö L, Anderberg A, Åslund I, Söderman O (2009) An improved method to validate the relative humidity generation in sorption balances. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 72:99–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.10.013

Wahba M, Nashed S (1957) Moisture relations of cellulose III. Sorption hysteresis and the effect of temperature. J Text Inst 48:T1–T20. https://doi.org/10.1080/19447025708659748

Wangaard FF, Granados LA (1967) The effect of extractives on water-vapor sorption by wood. Wood Sci Technol 1:253–277

Watt IC (1980) Adsorption–desorption hysteresis in polymers. J Macromol Sci A 14:245–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222338008066635

Weichert L (1963) Investigations on sorption and swelling of spruce, beech and compressed beech wood at temperatures between 20 °C and 100 °C. Holz Roh Werkst 21:290–300

Williams DR (1995) The characterisation of powders by gravimetric water vapour sorption. Int LABMATE 20:40–42

Wolf M, Walker JE, Kapsalis JG (1972) Water vapor sorption hysteresis in dehydrated food. J Agric Food Chem 20:1073–1077. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf60183a021

Xie Y, Hill CAS, Jalaludin Z, Sun D (2011) The water vapour sorption behaviour of three celluloses: analysis using parallel exponential kinetics and interpretation using the Kelvin–Voigt viscoelastic model. Cellulose 18:517–530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-011-9512-4

Zillig W (2009) Moisture transport in wood using a multiscale approach. Dissertation, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven

Acknowledgments

Bengt Nilsson is gratefully acknowledged for running the sorption balance measurements. Funding from the Swedish Research Council FORMAS (Grant No. 2013-1024) and the VILLUM FONDEN postdoc programme is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This work is dedicated to the memory of the late Dr. Preben Hoffmeyer (1939–2018).

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Fredriksson, M., Thybring, E.E. Scanning or desorption isotherms? Characterising sorption hysteresis of wood. Cellulose 25, 4477–4485 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-018-1898-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-018-1898-9