Abstract

Social Ecological System (SES) research highlights the importance of understanding the potential of collective actions, among other factors, when it comes to influencing the transformative (re)configuration of agri-food systems in response to global change. Such a response may result in different desired outcomes for those actors who promote collective action, one such outcome being food sovereignty. In this study, we used an SES framework to describe the configuration of local agri-food systems in Andean Ecuador in order to understand which components of the SES interact, and how they support outcomes linked to five food sovereignty goals. Through a survey administered to mestizo and indigenous peasants, we analyze the key role played by the Agroecological Network of Loja (RAL) in transforming the local agri-food system through the implementation of a Participatory Guarantee System (PGS). This study demonstrates that participation in the RAL and PGS increases farmers’ adoption of agroecological practices, as well as their independence from non-traditional food. Additionally, RAL lobbying with the municipality significantly increases households’ on-farm income through access to local markets. Being part of indigenous communities also influences the configuration of the food system, increasing the participation in community work and access to credit and markets, thus positively affecting animal numbers, dairy production and income diversification. The complexity of the interactions described suggests that more research is needed to understand which key factors may foster or prevent the achieving of food sovereignty goals and promote household adaptation amid high uncertainty due to global change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The conceptualization of agri-food systems as Social Ecological Systems (SES) is having a notable impact in agri-food research focused on sustainability (Ericksen 2008; Prosperi et al. 2016; Marshall 2015) and involves the following aspects: developing new methodological frameworks that integrate the socio-economic, institutional and environmental dimensions of the agri-food system; analyzing the interactions that are taking place between the different components in production, transformation, commercialization and consumption activities; and understanding the potential outcomes resulting from such interactions. This conceptualization allows for agri-food to be studied as a dynamic system in its entirety and managed accordingly, with the associated critical feedback on temporal and practical scales (Thompson and Scoones 2009).

SES-based research highlights the importance of understanding the role played by collective action in influencing outcomes; that is, the transformative (re)configuration of agri-food systems in the face of multiple drivers of change. Collective action plays a key role in the management of complex SES, facilitating cross-level governance, the long-term protection of ecosystems and the well-being of different populations (Ostrom 1990; Brondizio et al 2009; Cox et al 2010; Ostrom and Cox 2010; Anderies and Janssen 2013). Specifically, the literature demonstrates that informal institutions, e.g. networks based on reciprocity and trust, may determine the level of success of collective action (Ostrom and Ahn 2003). Steins and Edwards (1999) studied how nested platforms (i.e. ones including different levels of decision-making) with different user groups may facilitate ecologically, economically, and socially-sustainable resource management by emphasizing social learning and collective action. In a case study of quinoa producers and short value chains in Bolivia Winkel et al. (2020) demonstrated that communing processes may facilitate social-economic inclusion and sustainability. Collective action has also been found to be essential in promoting food security (Pelletier et al. 1999).

Food sovereignty has been proposed as political proposal capable to transform agri-food systems towards sustainability and conceptualised into a set of pillars, categories and indicators to facilitate its analysis (Ruíz-Almeida and Rivera-Ferre 2019). Several studies have shown how diverse and subaltern struggles -such as those based on collective action involving peasants, indigenous and women in many different contexts and aimed at promoting agroecology and food sovereignty- have the potential to transform agri-food systems (Martínez-Torres and Rosset 2014). Prior studies in the Peruvian Andean context have linked the role of barter markets -as an example of community-based collective action- to food sovereignty, mainly related to the promotion of social reciprocity and ecological diversity (Argumedo and Pimbert 2010). Some other studies have also demonstrated that the role of peasants and indigenous and other social movements in Ecuador has been pivotal in the push towards institutionalizing food sovereignty at the national level, both within the Constitution and policy design (Giunta 2014). In addition, research based on the sustainable rural livelihoods framework has emphasized the need to study the social and economic characteristics of context-specific agri-food systems, including market integration and income-generation strategies to support well-being and natural resource sustainability, and the capacity of rural communities and agri-food systems for transformative adaptation (Thompson and Scoones 2009).

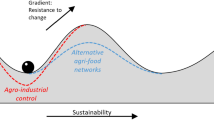

SES-based research and food sovereignty studies are normally assessed independently. The aim of this article is to combine the two frameworks to understand how innovative collective action interacts and reorganizes the components of the local agri-food system, conceptualized as an SES, and has significant impacts on food sovereignty outcomes (Vallejo-Rojas, Ravera and Rivera-Ferré 2015). Additionally, the article explores whether other concurrent factors, such as being part of indigenous comunas (i.e. the communal ancestral institutions) and having certain socio-economic characteristics, are also relevant in shaping agri-food systems. Our findings have multiple implications when it comes to policy design aimed at supporting adaptive transformations in the face of multiple drivers of change.

The framework is applied to a case study in the south Ecuadorian Andes. Our work was conducted with an informal agroecological innovative network of women mestizo and Saraguro indigenous peasants, the Agroecological network of Loja (Red Agroecológica de Loja in Spanish, hereafter RAL), which implements a Participatory Guarantee System (hereafter PGS). In studying this empirical case, the aims are to (1) select the most relevant variables that describe the local SES and its current configuration (i.e. architecture); (2) assess which key institutional and or socio-economic factors explain a set of outcomes in terms of food sovereignty; and (3) discuss the key role of the RAL and other factors in transforming the local agri-food system towards food sovereignty. The conclusions highlight the implications of the findings with regard to future policy.

Theoretical and methodological framework

In order to conceptualize and analyze the agri-food system as a whole, we have made use of the socio-ecological systems (SES) and the food sovereignty conceptual frameworks.

Ostrom (2009) developed the SES model to analyze complex systems. It tackles both ecological and socio-economic elements of the system and organizes them into Actors (A), Governance System (GS), Resource Systems (RS) and Resource Units (RU). Within this conceptualization, the elements are impacted by external drivers of change, both socio-economic (S) and ecological (ECO). The model analyzes how these drivers affect the components of the system through interactions (I) that result in different outcomes (O) and a new configuration of the system. One important characteristic of the model is that it systematically organizes all components of the system into different tiers of variables. To analyze current configurations of the agri-food system within a case study, we developed an integrated framework that links the social and ecological components of the agri-food system conceptualized as an SES to the food sovereignty as described by Ruiz-Almeida and Rivera Ferre (2019) (Fig. 1). To this end, we adopted Ostrom’s terminology to classify the second-tier variables of the SES framework (McGinnis and Ostrom 2014) (Appendix 1 in Table 2).

Methodological framework (adapted from McGinnis and Ostrom 2014). On the left, the ecological subsystems (RS and RU, green boxes), and on the right, the social subsystems (GS and A, blue boxes) with their respective scales and levels. For each subsystem, we highlight the main links with food sovereignty pillars (yellow boxes). In the center, the agri-food activities and outcomes (red boxes). (Color figure online)

The food sovereignty framework was developed by the international peasant movement La Vía Campesina (LVC) in 1996 as an alternative to the globalized and industrialized food system challenging the current food regime (McMichael 2011). The most commonly used definition of food sovereignty is the one that emerged from the Declaration of Nyéléni, first drafted at a forum held in Mali in February 2007, which states that: “Food sovereignty is the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems. It puts the aspirations and needs of those who produce, distribute and consume food at the heart of food systems (…)”. (Nyéléni Movement for Food Sovereignty 2015). LVC describes the food sovereignty movement as a counter-hegemonic “movement of movements” that, through collective action, attempts to radically transform the neo-liberal food regimen in favor of an environmentally sustainable and socially just agri-food system (La Via Campesina 2009; McMichael 2011). Many scholars agree that this policy proposal has the potential to reduce hunger and rural poverty (Altieri 2009; Wittman 2011) and further the move towards sustainable rural development (Rosset et al. 2011). On more of a policy level, multilateral institutions (e.g. the UNEP, the Commissioner of the Right to Food, the FAO, the UN Committee on Food Security) and governments (e.g. those of Mali, Nepal, Indonesia, Ecuador, Bolivia) have acknowledged its potential in the development of sustainable agri-food systems (Brem-Wilson 2015). To analyze the potential of food sovereignty in achieving sustainability goals, indicators have been developed at both the local (Binimelis et al. 2014) and global (Ortega-Cerdà and Rivera-Ferre, 2010; Ruiz-Almeida and Rivera-Ferre 2019) levels. Measuring food system outcomes in terms of food sovereignty allows new trends to emerge that will be useful for policy-makers (see Oteros-Rozas et al. 2019). For this case study, we used indicators related to five food sovereignty pillars adapted by Ortega-Cerdà and Rivera-Ferre (2010): (1) Access to Resources, which includes the access human, financial and natural resources; (2) Production model, which refers to both the land and labor organization and the management practices adopted based on agroecology; (3) Transformation and Commercialization, which includes indicators of transformation practices, prices, access to markets; (4) Food Security and the Right to Food, which includes indicators of the food and nutritional security, but also access to culturally appropriate food and dependence from buying food; (5) Agrarian policies and Civil Society Organizations, which include degree of organization, participation and lobbying capacity of peasants.

Methodology

Background information on the case study

Our study focuses on the Andean agro-ecosystem in the canton and province of Loja, located in the southern Ecuadorian Andes, in the parishes of San Lucas (3° 44′ 47.5′′ S, 79° 15′ 58.5′′ W) and Jimbilla (3° 51′ 39.5′′ S, 79° 10′ 22.2′′ W) (Fig. 2).

The agricultural calendar for this region (Fig. 3) has a rainy season from September to May and a dry season from June to August. The agricultural calendar is linked to traditional Andean indigenous celebrations (shown in the outer circle). The rainy season corresponds to September to May (periods of high rainfall are usually during October and March–April), and the dry season to June to August. Kulla Raymi (a Quichua word that means Queen festival dedicated to the moon) begins on September 21. The crops cultivated in this season are: corn associated with bean, squash and other Andean crops. Following the summer austral solstice (Kapac Raymi, which in Quichua means wisdom festival), barley and wheat are planted in January. After March 21 (Pawkar Raymi, or flowering festival in Quichua), the fresh bean harvest begins. In April, potatoes and peas are planted. On June 21, Saraguro and other ancestral communities celebrate the Sun festival (Inti Raymi, in Quichua) and this is the period of the ripe corn, barley and wheat harvests (MBS-SSDR/IFAD/IICA 1991; Neill and Jørgensen 1999; INAMHI 2014a; INPC 2012). The area where corn is grown alongside Andean crops (e.g. beans, potatoes) is locally known as chacra, while the huerta is mainly dedicated to planting short-cycle vegetables. Crops are also distributed according to altitude.

Provincial data show that the population of Loja canton corresponds to 2.5% of the country’s total population. It is predominantly urban (79%) and mestizoFootnote 1 (83%), the indigenous population (10%) comprising a considerably smaller proportion of the total population (INEC 2010). For 48% of the population, income derives from on-farm activities (INEC 2010), while off-farm work is also a relevant strategy of income generation for 63% of the population (of the latter, 34% is not related to the agricultural sector) (INEC 2010). Only 14% of agricultural production units (APUs) sell their production directly to consumers (SINAGAP 2000), while 51% are smaller than 5 ha and occupy 6% of the land area. The largest units (which are over 100 ha) represent 2% of local APUs, occupying 40% of the land area.

The largest indigenous group is the Saraguro people, a large and diverse Quechua group (INPC 2012). Though the Saraguro agro-pastoralist society has been heavily transformed and the economy diversified in recent times, including receiving income through remittances due to high rates of migration to the US and Spain, most Saraguros maintain their distinctive ethnic identity through ceremonies, clothing, observing the wakas, i.e. natural sacred beings, etc. Saraguro culture still maintains an agro-centric spirituality and knowledge system (Bacacela 2010).

The indigenous peoples and mestizos live within community-based organizations, i.e. the traditional indigenous comunas and farmers’ associations. The comunas are groups of indigenous people with formal rules drafted in coordination with the Ministry of Agriculture (Martínez 1998). These organizations are governed by the Law of Commons (1937) and have the cabildo as their representative body (Martínez 2002). In Saraguro communities, the cabildo is therefore the central entity of political organization (Ávila 2012; INPC 2012). Land ownership is individual and neither the community nor its leaders control rights over the land or water supply (Belote 2002). However, mobilizations by Saraguro communities in relation to land struggles played a decisive role in an indigenous uprising during the 1990s (Rosero 1990, cited in Criollo 1995, p. 164), and the community currently plays a key role in decision-making on land uses and economic activities, such as communitarian tourism (Ordoñez Sotomayor and Ochoa Cueva 2020).

Mostly organized by women, the RAL was created as a novel institutional arrangement in 2006. It comprises both indigenous (i.e. Saraguro) and mestizo traditional farmers’ organizations and is linked to the transnational peasant movement La Vía Campesina. The RAL was created as a response to rapid socio-economic, cultural and political changes that were affecting both social organization and culture (Martínez 2005, 2002), the loss of traditional crops and foods (Espinosa 1997; Sherwood et al. 2013) and the progressive dependence on intermediaries in urban markets (Proaño and Lacroix 2013; Chiriboga and Arellano 2004). As in other cases of agroecological counter-movements in Ecuador, the emergence of RAL met with a favorable political environment, i.e. the new Constitution of Ecuador adopted in 2008 (Asamblea Nacional 2008), which included food sovereignty as a strategic objective (Art. 281) (Intriago et al. 2017). Additionally, in 2009, the Food Sovereignty Law (LORSA) was approved to provide a legal framework for food sovereignty. At the time of this study, the RAL was composed of 17 producer organizations and had established three associative spaces in the city of Loja in the form of weekly agro-ecological fairs. At the core of the RAL’s governance system is the Participatory Guarantee System (PGS). PGS are networks created within local communities that provide certification for producers based on active participation by stakeholders and are built on a foundation of trust, social networks and knowledge exchange (Loconto and Hatanaka 2018). The RAL uses the PGS as a validation tool for implementing agroecology at the farm level and as a consumer warranty regarding the type and quality of products. The RAL is coordinated with the municipality of Loja and the local public university for the access to local markets and training.

Data collection

First, a literature review was conducted in order to collect context-specific data and complementary information and have references to other mountain area studies. In order to design the survey, informal visits were undertaken to the area in December 2014 to carry out in-depth interviews with key informants (N = 14). The survey was then administered in four communities in the parishes of San Lucas and Jimbilla. The sample was deliberately skewed in order to capture the cultural, institutional and ecological diversity of the agrarian dynamic in this Ecuadorian Andean region (Cepeda, Gondard, and Gasselin 2007). Regarding cultural diversity, both indigenous Saraguro (N = 59) (81% of the San Lucas population) and mestizo households (N = 57) (95% of the Jimbilla population) were interviewed (INEC 2010). To cover institutional diversity, we also included a number of households in the communities that belonged to indigenous comunas (N = 34) and the RAL (N = 24). Finally, to capture ecological diversity, the interviewed households were located in different altitudinal zones, from low (1800-2200 m.a.s.l.; N = 24) to middle (2200-2600 m.a.s.l.; N = 61) and high (2600-3000 m.a.s.l.; N = 31) zones (Cueva 2010). The survey participants comprised 60% women and 40% men (householders aged between 18 and 89 years). The questionnaire included information on: (i) household (e.g. size and division by age and gender) and individual (e.g. ethnic self-identification and educational level) characteristics; (ii) production activities (e.g. access to and uses of land, credit, training, agricultural practices, crops and livestock management, commercialization); (iii) processing and distribution activities (e.g. artisanal processing, commercialization, access to markets and incomes sources); (iv) consumption activities (e.g. consumption habits); and (v) social relations (e.g. participation in social exchanges such as minga [exchange of work for food, mainly for community purposes], prestamanos or randi-randi in Quechua [exchange of work for work, mainly at the household level], exchange of seeds and community-based organizations. All survey sections included questions about: rights (e.g. access to land); agency (e.g. decisions about crops and livestock management); and power (e.g. role of gender in division of tasks and responsibilities within the household in the different agri-food activities).

Data analysis

We qualitatively analyzed the content of interviews from key local informants, and triangulated this information with the literature review to define and classify a series of variables that describe the configuration of the agri-food system. These were classified as explanatory (i.e. those variables from Actors and Governance subsystems that might influence the behavior of other components and their interactions), intermediate (i.e. those variables that are relevant in influencing the configuration of agri-food activities but at the same time can be influenced by other explanatory variables targeted by our study), or control variables (i.e. those variables that could influence the configuration of agri-food activities but did not form part of our target study goal). Some of these variables also influence the components of agri-food activities (dependent variables, in our case, linked to food sovereignty pillars).

A Redundancy Analysis (RDA) was performed to select the main variables influencing the configuration of the agri-food system. RDA is a form of constrained ordination that examines how much of the variation in one matrix of explanatory variables explains the variation in another matrix of response variables (Leps and Smilauer 2003). The explanatory and control variables were included within the explanatory matrix, and the dependent and intermediate variables were included within the response matrix. Prior to performing the RDA, we applied a log-transformation (Leps and Smilauer 2003) to all of the numerical and ordinal variables.Footnote 2 In order to exclude collinear variables from the model, we performed a collinearity test using the variance inflation factor (VIF); a VIF > 10 indicates that a variable has a high level of collinearity (Zuur et al. 2010; Oksanen 2013). We then applied a model-building technique to reduce and find the significant variables (from the explanatory matrix) that determine the configuration of the agri-food system (i.e. response matrix) in this case study. Model building was performed using the step function (Oksanen 2013) from the Community Ecology Vegan R Package software (Oksanen et al. 2015). The step function uses Akaike's information criterion (AIC) to select the best model from among all the possible combinations of available variables within the explanatory matrix. To validate the model’s prediction, the function uses a permutation test at each step. Thus, all included variables in the final model are significant and all excluded variables not significant (Oksanen 2013). The results of the RDA were visualized using a biplot graph.

In order to evaluate the key role socio-economic and institutional factors play in components of agri-food activities, we conducted non-parametric bivariate testsFootnote 3 using SPSS statistics for each significant variable obtained from the RDA. Finally, to understand the configuration of the agri-food system in terms of food sovereignty, we linked the five food sovereignty pillars with significant dependent and intermediate variables for each agri-food activity.

An overview of the variables used for the different analyses performed in the study and their links to food sovereignty pillars is provided in Table 1 and Appendix 2 in Table 3.

Results

Our results indicate a statistically significant association (p < 0.0001, from 999 permutations) among the most relevant institutional and socio-economic factors that determine the configuration of the agri-food system in our case study. The results of the RDA analysis and the biplot representation are shown in Fig. 4. The RDA mainly revealed the trade-off association between income generation strategies (on-farm strategies vs off-farm work) and ecological (RU5.1; RU5.2; RU6.1) and economic (A8.5) diversification. The analysis also revealed that households with larger land size (RS3 Land size) often have on-farm income generation strategies. Two further explanatory variables, i.e. membership to RAL and belonging to the indigenous Saraguro culture, were mainly associated with agroecological production practices (A9.1; A9.2; A9.3), a dependence on purchased food (A8.4), seed exchanges (A6.3), access to human resources (A2.5) and to market (GS5.1).

Redundancy analysis biplot showing the explanatory and control variables (labeled in black on arrows) that explain the configuration of the third-tier SES dependent and intermediate variables (labeled in blue). Small red circles represent the households surveyed on study (N = 116). Percentage variance explained: RDA 1 (67.72%), RDA 2 (19.36%)

In order to better understand how selected explanatory variables positively or negatively influence other variables of the agri-food system in the four activities (i.e. production, transformation process, distribution, consumption), bivariate tests were performed (see Fig. 5 and Appendix 3 in Table 4 for details). Links with food sovereignty pillars were also analyzed.

Description of the role played by the following explanatory variables: Indigenous Saraguro, marketing of agri-food products and off-farm works, Agroeological network of Loja (RAL) in configuring the agri-food system through agri-food activities. The diagram shows the statistical significance of the relationship between each explanatory variable and their intermediate and dependent variables. Letters within brackets show how each component of the agri-food system relates to the food sovereignty pillars: a access to resources, b production model, c local markets, d right to food, e social organization

On-farm income generation strategies

This variable correlated positively with number of cattle (RU5.3), crop (RU5.1) and small animal (RU5.2) richness in production activities, i.e. production model pillar. With regards to distribution activities, on-farm income generation strategies displayed a positive correlation with income diversification (A8.5), i.e. production model pillar. With regards to consumption activities, a positive correlation was found with dietary diversity produced (RU6.1), and a negative one with importance of small animals for self-consumption (A8.2) and the dependence of non-traditional purchased foods low in micronutrients (A8.4), i.e. food security and right to food pillar.

Off-farm work income generation strategies

The variable off-farm work displayed a negative correlation with agroecological practices, such as the use of ethno-veterinary products (A9.3), i.e. production model. Pillar. Concerning distribution activities, off-farm work had a positive correlation with participation in community-based working groups (A6.1), i.e. social organization pillar, which in turn also influenced income diversification (A8.5), but it displayed a negative correlation with importance of on-farm incomes (A8.6), production model pillar. With regards to consumption activities, off-farm work had a negative correlation with dietary diversity produced (RU6.1), i.e. food security and right to food pillar.

The indigenous Saraguro culture

With regards to production and processing activities, indigenous Saraguro commmunities has a positive correlation with access to credit (A2.6) and a negative one with training (A2.5), i.e. access to resources. Furthermore, access to credit positively influenced number of cattle (RU5.3) and processed dairy production (RS5.1), access to resources and production model pillars. According to our survey and interviews, access to credit in the study area has occurred mainly through savings and credit cooperatives (69%), i.e. through the private sector. With regards to distribution activities, being Saraguro had a positive influence on weekly frequency of selling (A8.8). Additionally, being Saraguro has a marginally significant positive correlation with participation in community-based working groups (A6.1), social organization pillar, which in turn also influenced income diversification (A8.5), i.e. production model pillar.

RAL collective rules

With regards to production activities, the RAL collective’s rules displayed significant positive correlations with agroecological practices, such as the use of organic inputs on crops (A9.1) and ethnoveterinary practices (A9.3); and a negative correlation with conventional practices, such as the use of chemical inputs on crops (A9.2), i.e. production model pillar. Additionally, the RAL collective’s rules has a significant positive correlation with access to training (A2.5), which in turn also influenced agroecological practices. Participation in seed exchanges (A6.3), i.e. social organization pillar, was also found to correlate with RAL, influencing crop richness (RU5.1), production model pillar. With regards to distribution activities, the RAL had a significant positive correlation with importance of on-farm incomes (A8.6), i.e. production model pillar. Additionally, the RAL had significant positive correlation with participation in services exchanges (A6.2), social organization, and access to retail location (GS5.1), i.e. commercialization, which in turn also influenced the importance of the on-farm income variable. With regards to consumption activities, the RAL had a significant negative correlation with dependence on non-traditional purchased foods low in micronutrients (A8.4), i.e. food security and right to food, which in turn was also influenced by training.

Discussion

Do economic factors matter when it comes to configuration of the agri-food system and food sovereignty goals?

First of all, our results confirm that the commercialization of agri-food products as an on-farm strategy for income generation, through both normal local market and PGS mechanisms, contributes to income diversification within the household, as suggested in the literature (Minot et al. 2006). Secondly, this strategy influences agro-biodiversity at the farm level, as suggested for other contexts by Major et al. (2005) and Trinh et al. (2003). Households that market their own agri-food products had higher levels of diversity in terms of crop and animal richness; and, as noted by other studies (Herforth 2010; Jones et al. 2014), this richness is associated with high levels of dietary diversity produced. In sum, the commercialization of agri-food products increases control over food sovereignty in the production model and right to food pillars. Moreover, through the positive influence of on-farm production diversity the diversity it also increases the diversity of households diets, an important nutritional outcome associated with the nutrient adequacy of diets and individuals’ nutritional status (Jones et al. 2014). The results illustrate that such households have low levels of dependence on non-traditional purchased foods low in micronutrients. Since food consumption of low nutritional quality, especially in areas with fewer economic resources, is a public health problem in Ecuador (Freire et al. 2013), these results are important for understanding the potential capacity of local agri-food systems to meet human nutritional needs in fragile and marginal areas, i.e. to impact food sovereignty in the right to food pillar. However, our results also show that households that market their own agri-food products score lower in own consumption of small animals, due to the fact that they sell them. This is an undesirable outcome related to the consumption of nutritional foods within the right to food pillar, and is consistent with the findings of recent studies performed in the Ecuadorian Andes (Oyarzun et al. 2013; Berti et al. 2014) as well as studies found elsewhere in the Andean region (Berti et al. 2010).

Regarding the influence of off-farm work on the configuration of the agri-food system, we found that this type of strategy supports income diversification (Ellis 2000), helping to increase farm income for rural households living at subsistence level and thus, to diversify against risk (Reardon et al. 2001; Lanjouw 1999). However, it also leads to lesser importance for revenue obtained from the marketing of farm products and a lower dietary diversity, which can influence the food consumption at the household level. Given that the production model is intensive in labor in the region concerned, this lower diversification may influence the reduction of available labor within households for agriculture (Rozelle et al. 1999; Pfeiffer et al. 2009). In sum, families with an off-farm strategy have a deficit of control over the production model and the food security and right to food pillars of food sovereignty. Unexpectedly, our findings reveal a relationship between participation in the community based on ties and work (social organization pillar), expressed through mingas, and income diversification (production model pillar). In respect of this, other studies have shown the importance of social ties in securing off-farm work by linking farm residents to jobs outside the farm property and/or influencing their likelihood to participate in off-farm work (Vanwey and Vithayathil 2013). That being said, however, we cannot fully confirm these findings from the available data, especially given that other studies on Ecuadorian Andean communities (Martínez 1996) have noted that mingas (e.g. communal works such as water supply and road construction) are implemented when communal action participation is high. Therefore, this variable could be acting as a contextual factor. Finally, regarding the economic characteristics of the household, our results suggest that livelihood decisions are strongly affected by the amount of land owned by the family. Households with small farms are more likely to have off-farm work in order to diversify their income sources (Escobal 2001; Lanjouw 1999), while having more land means being able to maintain livestock, the main activity linked to an on-farm income generation strategy in the area of study (Belote 2002; Pohle et al. 2010).

To sum up, then, our findings suggest that generating income through an off-farm strategy interacts with food sovereignty goals in opposing ways, specifically by decreasing the control over the production model and right to food pillars, while also increasing the household’s social organization and, thus, its diversification.

Does belonging to mestizo or indigenous communities matter in the configuration of the agri-food system and food sovereignty goals?

The Andean research community has highlighted the role of socio-cultural characteristics that link indigenous cultures and knowledge to local configuration of the agri-food system and adaptation to changes (Garay and Larrabure 2011; Velásquez-Milla et al. 2011). Our findings contribute to those of the aforementioned studies, showing that indigenous communities and their social capital facilitate access to other forms of capital, both directly and through engaging with State, market, and other civil society actors (Bebbington and Perreault 1999; Perreault 2003). This influence can be assessed through both ecological and socio-economic components of the local agri-food system. Being part of the indigenous culture therefore facilitates access to credit, mainly to support livelihood strategies related to livestock management (i.e. the production model pillar). This result is corroborated by those from other studies on Saraguro culture and shows that livestock ownership (jointly with land) is an indicator linked to success in local livelihoods (Belote 2002), which are mainly based on keeping animals and income from selling cheese (Belote 2002; Pohle et al. 2010). In line with other research (Belote and Belote 2005), our findings show that Saraguro people also display high diversification when it comes to income, given that migration to urban areas and/or foreign countries has been an common adaptation strategy. In respect of this, access to a paved road in San Lucas parish is a contextual factor that positively links to being part of Saraguro communities and would appear to be relevant to distribution activities, thus influencing sales frequency and income diversification. This result corroborates other findings showing that access to road infrastructure systems has a cascade effect on access to local markets, the development of multiple activities and income diversification (Castaing et al. 2015; Bernardi De León 2009).

All that being said, access to training is negatively related to the Saraguro indigenous group, and we observe here that they have less access than mestizo people to the information necessary to adopt agricultural practices (González et al. 2010). Thus, our results confirm that indigenous people rely more on local and horizontal networks within the community and traditional ecological knowledge for farming (the social organization pillar of food sovereignty). However, no difference was found to be associated with membership of the comuna or not. As noted by Belote (2002), Saraguro communities do not act as regulatory units, which may explain why this institutional factor was not significant in the indicators used here describing the local agri-food system.

In sum, from a food sovereignty perspective, our results suggest that in the configuration of the local agri-food system in Loja, indigenous Saraguro culture plays a central role in positively influencing social organization, and therefore control over access to resources, the production model and local markets.

Does participating in the RAL matter when it comes to configuration of the agri-food system and food sovereignty goals?

Our findings make a further contribution to studies based on agri-food sociology and agroecology research by showing that collective organization under the agroecological paradigm is the core on which food sovereignty components are built (Rosset et al. 2011; Simoncini 2015; Gyau et al. 2014; Rosset and Altieri 2017; Oteros-Rozas et al. 2019). In our case, the RAL facilitates access to training (specifically in this case, agroecological training through contacts with the local public university) and participation in seed exchange (i.e. access to the resources pillar), which in turn positively influences the adoption of agroecological production practices and agro-biodiversity (i.e. the production model pillar). Prior studies and our key informants both point to the key role played by social organization in the adoption of agroecological practices through a diálogo de saberes (dialogue of wisdoms) (Martínez-Torres and Rosset 2014), e.g. in agroecology or farmers’ schools (McCune et al. 2014) and/or in meetings organized by these networks as seed exchange fairs (Hermann et al. 2009). With its system of collective rules, of which the PGS constitutes the core, the RAL strengthens and monitors the implementation of agroecological practices on the farms owned by its associate producers. Previous studies have also highlighted the key role of PSGs in strengthening agroecological practices (MAGAP 2012; Binder and Vogl 2018).

Being a member of the RAL also increases the importance of on-farm income, and access to markets may explain the diversification of income due to on-farm activities within RAL households. In fact, this is one of the pillars strengthened most by the RAL, due to it performing lobbying activities with the municipality (Vallejo-Rojas, Ravera and Rivera-Ferre 2015). Other Ecuadorian agroecological networks (Chauveau et al. 2010; MAGAP 2012; Proaño and Lacroix 2013) have also achieved these desirable outcomes within distribution activities. Regarding eating habits at the household level, our findings reveal the importance of the RAL when it comes to access to training, due to it performing lobbying activities with NGOs and the collective rules and social ties built by the organization. The RAL’s collective rules establish that food production must first focus on meeting household nutritional needs, forcing the marketing of agri-food products into second place. This is relevant because it avoids the undesirable effects of indicators linked to the strategy of commercializing agri-food products within the right to food pillar, like those related to low levels of self-consumption (explained above). Additionally, social ties between mestizos and indigenous people strengthen the exchange of knowledge in the gastronomic and nutritious fields. Previous studies have also highlighted the role of social networks as determinants of consumer habits (Fonte 2013; Williams et al. 2015). Moreover, the relationship between RAL and service exchanges is an important aspect within Ecuadorian Andean communities, where these forms of exchange are becoming increasingly scarce (Martínez 2002). Reciprocity contributes to the development of long-term obligations between people, which is an important part of achieving positive environmental outcomes in agri-food systems (Pretty and Smith 2004). Both prior studies and our key informants indicate that these exchanges are mainly related to on-farm activities (e.g. planting, harvesting) (Martínez 1996; Gray 2009).

In sum, from a food sovereignty perspective these findings suggest that RAL’s collective rules play a pivotal role in the interaction between the pillars of social organization and agri-food policy, increasing access to the right to food and production model pillars.

RAL is a network led by and mainly comprising women. Like other scholars (Gray 2009), we observed that in rural parishes of Loja province, the number of women working in the farm household increased due to male-driven migration and remittances. Indeed, in our area of study, men are often engaged in off-farm work (Vallejo-Rojas et al. 2015) mainly linked to the construction sector (INEC 2010), which diversifies their sources of income, while women have increased their participation in on-farm labor, confirming an increased female presence in agricultural activities (Deere 2005; Katz 2003). Secondly, we observe that in our case study the adoption of an agro-ecological production model is strictly related to the existence of a collective agency built by the RAL. Women members of RAL have united their efforts, independently of ethnic and class divisions, and through the organization’s rules (at a collective level) achieved the successful adoption of the agro-ecological production model (at a farm level) and access to local markets (at a collective level) by lobbying government and nongovernment organizations. Additionally, in the interviews conducted within this research, women highlighted an increase in self-esteem and economic independence (at an individual level) as a result of participating in the RAL. Despite these data requiring more in-depth research, they confirm the findings of other studies on collective agency and women (Agarwal 2000; Gabrielsson and Ramasar 2013; Bezner-Kerr et al. 2019). Recent studies in the Ecuadorian Andean context (Cole et al. 2011) have also suggested that women’s greater understanding of crop management options and more equal household gender relations are associated with conventional practices being less widespread.

Conclusions

By combining the SES and food sovereignty frameworks in a local Ecuadorian Andean case study, we have analyzed which variables and factors interact in the local agri-food system, contributing to an understanding of its current configuration when conceptualized as a social-ecological system. Most food sovereignty-related research to date has shown, mainly through qualitative methodologies, the key role of social organization and collective action as a central component in advancing the proposal for food sovereignty. Our study contributes to this literature by quantitatively demonstrating how being part of the RAL and participating in the PGS foster this proposal in practice.

The links and interacting effects between the variables in our study are complex and non-linear. More research in different contexts is required to determine which cross-scale factors either enhance or pose a barrier to food sovereignty goals, and which are most relevant in promoting household adaptation amid the high uncertainty of global environmental change (e.g. how household diversification fosters risk diversification) or making it more difficult (e.g. off-farm work linked to small farms and lack of access to land). Such an understanding may help future policy design. Historically, the role played by Ecuadorian governments in agri-food policies has focused on the agro-export model, in detriment of peasant and small-farmer agriculture (Rosero et al. 2011). As a response to this, there has been a progressive emergence, consolidation and expansion of counter-movement spaces aimed at agroecology and food sovereignty (Intriago et al. 2017). Our study focuses on this re-configuration of local agri-food systems and suggests that interventions need to focus on the production model promoted by agro-ecological organizations, while including programs aimed at enhancing the role of formal and informal organizations involving both peasants and indigenous communities, strengthening their alliances with consumers. Similarly, government investments aimed at generally improving the nutrition and health levels of the population should include those collaboration programs with agroecological networks that are likely to have the broadest and greatest impact on consumer habits within the rural sector at the household level and provide greater nutritional diversity. That being said, those agricultural programs that focus on a single crop and off-farm income generation may make smallholder farms and farming families more vulnerable, resulting in poorer ecological, nutritional and economic outcomes of the agri-food system from a food sovereignty perspective. Additionally, regarding policy focusing on conservation, policy-makers interested in promoting the sustainable use of natural resources (soil, water, forest) need to consider not only including communities living in protected areas within conservation programs, but also the role of informal networks to improve the adoption of sustainable local production practices in and around protected areas. In sum, ignoring the role of social and institutional factors could represent a missed opportunity to improve the management of Ecuadorian agri-food systems across scales.

Finally, we would note that, in part, ensuring food sovereignty means not only implementing agroecological solutions but also dealing with power relationships in the productive system and specifically on gender roles, rights and involvement in decision-making (Patel 2012; Bezner-Kerr et al. 2019). This topic certainly deserves more attention in future research.

Notes

Cultural and biological mix of Spanish and indigenous people (Belote 2002).

We used ln(x) for this, and for those variables that range from zero, ln(x + 1).

The Mann–Whitney-U test was used for numerical variables, and the chi-squared test for nominal, dummy and ordinal variables.

Abbreviations

- RAL:

-

Agroecological Network of Loja (in Spanish Red Agroecológica de Loja)

- PGS:

-

Participatory Guarantee System

- LVC:

-

La Vía Campesina

- SES:

-

Socio-Ecological Systems

- RDA:

-

Redundancy Analysis

- A:

-

Actors

- GS:

-

Governance System

- RS:

-

Resource Systems

- RU:

-

Resource Units

- S:

-

Socio-Economic Drivers

- ECO:

-

Ecological Drivers

- I:

-

Interactions

- O:

-

Outcomes

- APUs:

-

Agricultural Production Units

- VIF:

-

Variance Inflation Factor

- AIC:

-

Akaike's Information Criterion

- INEC:

-

Instituto Nacional Estadística y Censos

- MAGAP:

-

Ministerio de Agricultura, Ganadería, Acuacultura y Pesca

- INPC:

-

Instituto Nacional del Patrimonio Cultural

- UNEP:

-

United Nations Environmental Program

- FAO:

-

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

- UN:

-

United Nations

- SINAGAP:

-

Sistema Información Nacional Agricultura, Ganadería, Acuacultura y Pesca

- INAMHI:

-

Instituto Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología

References

Abdelali, M.M., B. Dhehibi, and A. Aw-Hassan. 2014. Determinants of small scale dairy sheep producers’ decisions to use middlemen for accessing markets and getting loans in dry marginal areas in Syria. Experimental Agriculture 50: 438–457. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0014479713000628.

Agarwal, B. 2000. Conceptualising environmental collective action: Why gender matters. Cambridge Journal of Economics 24 (3): 283–310. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/24.3.283.

Altieri, M. 1995. Agroecology: The scientific basis of alternative agriculture. Boca Raton, USA: Taylor and Francis Book.

Altieri, M. 2009. Agroecology, small farms, and food sovereignty. Monthly Review 61 (3): 102. https://doi.org/10.14452/MR-061-03-2009-07_8.

Anderies, J.M., and M. A. Janssen. 2013. Sustaining the Commons. Center for the Study of Institutional Diversity, Arizona State University

Argumedo, A., and M. Pimbert. 2010. Bypassing globalization: Barter markets as a new indigenous economy in Peru. Development 53 (3): 343–349. https://doi.org/10.1057/dev.2010.43.

Asamblea Nacional. 2008. Constitución de la República del Ecuador. Ecuador: R.O. N 449 de 20 de octubre de 2008.

Ávila, L. F. 2012. Disputas de Poder y Justicia: San Lucas (Saraguro). In Justicia Indígena, Plurinacionalidad e Interculturalidad En Ecuador, ed. Boaventura de Sousa Santos and J. Grijalva, 373–430. Quito, Ecuador: Abya-Yala.

Bebbington, A., and Th. Perreault. 1999. Social capital, development, and access to resources in highland ecuador. Economic Geography 75 (4): 395–418.

Belote, L. 2002. Relaciones Interétnicas en Saraguro 1962–1972. Abya-Yala.

Belote, L., and J. Belote. 2005. ¿Que Hacen Dos Mil Saraguros en EE.UU. y España? In La Migración Ecuatoriana Transnacionalismo, Redes e Identidades, edited by G. Herrera, M. Carrillo, and A. Torres, 449–66. Quito, Ecuador: FLACSO - Sede Ecuador.

Bernardi De León, R. 2009. Road development in podocarpus national park: An assessment of threats and opportunities. Journal of Sustainable Forestry 28 (6–7): 735–754.https://doi.org/10.1080/10549810902936607

Berti, P., C. Fallu, and Y. Cruz. 2014. A systematic review of the nutritional adequacy of the diet in the central Andes. Revista Panamericana De Salud Publica 34 (5): 314–323.

Berti, P., A. Jones, Y. Cruz, S. Larrea, R. Borja, and S. Sherwood. 2010. Assessment and characterization of the diet of an isolated population in the Bolivian Andes. American Journal of Human Biology 22 (6): 741–749. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.21075.

Bezner-Kerr, R., C. Hickey, E. Lupafy, and D. Laifolo. 2019. Repairing rifts or reproducing inequalities? Agroecology, food sovereignty, and gender justice in Malawi. Journal of Peasant Studies 46 (7): 1499–1518. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2018.1547897.

Binder, N., and Ch.R. Vogl. 2018. Participatory guarantee systems in Peru: Two case studies in lima and Apurímac and the role of capacity building in the food chain. Sustainability 10: 4644. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124644.

Binimelis, R., M.G. Rivera-Ferre, G. Tendero, M. Badal, and M. Heras. 2014. Adapting established instruments to build useful food sovereignty indicators. Development Studies Research 1: 324–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/21665095.2014.973527.

Brem-Wilson, J. 2015. Towards food sovereignty: Interrogating peasant voice in the United Nations Committee on World Food Security. The Journal of Peasant Studies 42 (1): 73–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2014.968143.

Brondizio, E.S., E. Ostrom, and O.R. Young. 2009. Connectivity and the governance of multilevel social-ecological systems: the role of social capital. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 34 (1): 253–278. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.environ.020708.100707.

Castaing, G., and B.G. NajmanRaballand. 2015. Roads and diversification of activities in rural areas: A Cameroon case study. Development Policy Review 33 (3): 355–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12111.

Castro, A., B. Martín-López, E. López, T. Plieninger, D. Alcaraz-Segura, C.C. Vaughn, and J. Cabello. 2015. Do protected areas networks ensure the supply of ecosystem services? Spatial patterns of two nature reserve systems in semi-arid Spain. Applied Geography 60: 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2015.02.012.

Cepeda, D., P. Gondard, and P. Gasselin. 2007. Mega Diversidad Agraria en el Ecuador: Disciplina, Conceptos y Herramientas Metodológicas para el Analisis-Diagnóstico de Micro-Regiones. In Mosaico Agrario, edited by M. Vaillant, D. Cedepa, P. Gondard, A. Zapatta, and A. Meunier. Quito, Ecuador: SIPAE, IRD, IFEA.

Chauveau, C., W. Carchi, P. Peñafiel, and M. Guamán. 2010. Agroecología y Venta Directa Organizadas, una Propuesta para Valorizar Mejor Los Territorios de la Sierra Sur del Ecuador. Cuenca, Ecuador: CEDIR-AVSF-FEM.

Chiriboga, M., and J.F. Arellano. 2004. Diagnóstico de la Comercialización para la Pequeña Economía Campesina y Propuesta para una Agenda Nacional de Comercialización Agropecuaria. Quito, Ecuador: RIMISP.

Cole, D., F. Orozco, W. Pradel, J. Suquillo, X. Mera, A. Chacon, G. Prain, S. Wanigaratne, and J. Leah. 2011. An agriculture and health inter-sectorial research process to reduce hazardous pesticide health impacts among smallholder farmers in the Andes. BMC International Health and Human Rights 11 (2): S6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-698X-11-S2-S6.

Cox, M., G. Arnold, and S. Villamayor. 2010. A review of design principles for community-based natural resource management. Ecology and Society 15 (4): 38.

Criollo, T. 1995. Economía Campesina y Estrategias de Sobrevivencia en Zonas de Altura Caso: San Lucas. Loja, Ecuador: CCE.

Cueva, J.L. 2010. Elaboración y Análisis del Estado de la Cobertura Vegetal de la Provincia de Loja-Ecuador. España: Universidad Internacional de Andalucía.

Deere, C. D. 2005. The Feminization of Agriculture? Economic Restructuring in Rural Latin America. Geneva, Switzerland: UNRISD

Domeher, D., and A. Raymond. 2012. Access to credit in the developing world: Does land registration matter? Third World Quarterly 33: 161–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2012.627254.

Dudley, N. 2008. Guidelines for appling protected areas management categories. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

Ellis, F. 2000. The determinants of rural livelihood diversification in developing countries. Journal of Agricultural Economics 51 (2): 89–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-9552.2000.tb01229.x.

Ericksen, P. 2008. Conceptualizing food systems for global environmental change research. Global Environmental Change 18 (1): 234–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2007.09.002.

Escobal, J. 2001. The determinants of nonfarm income diversification in Rural Peru. World Development 29 (3): 497–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00104-2.

Espinosa, P. 1997. Raíces y tubérculos andinos cultivos marginados en el Ecuador: situación actual y limitaciones para la producción. ABYA-YALA editor

Fadiman, M. 2005. Cultivated food plants: Culture and gendered spaces of colonists and the Chachi in Ecuador. Journal Latin American Geography 4: 43–57.

Fan, Sh., and C. Chan-Kang. 2005. Is small beautiful? Farm size, productivity, and poverty in Asian agriculture. Agricultural Economics 32: 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0169-5150.2004.00019.x.

Fonte, M. 2013. Food consumption as social practice: solidarity purchasing groups in Rome Italy. Journal of Rural Studies 32: 230–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2013.07.003.

Freire, W., M. J. Ramírez, P. Belmont, M. J. Mendieta, K. M. Silva, N. Romero, K. Sáenz, P. Piñeiros, L. F. Gómez, and R. Monge. 2013. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición del Ecuador. ENSANUT-ECU 2011–2013. Quito, Ecuador: MSP/INEC.

Fuentes, F., D. Bazile, A. Bhargava, and E. Martínez. 2012. Implications of farmers’ seed exchanges for on-farm conservation of quinoa, as revealed by its genetic diversity in Chile. Journal of Agriculture Science 150: 702–716. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021859612000056.

Gabrielsson, S., and V. Ramasar. 2013. Widows: agents of change in a climate of water uncertainty. Journal of Cleaner Production 60 (12): 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.01.034.

Garay, E., and J. Larrabure. 2011. Relational knowledge systems and their impact on management of mountain ecosystems: Approaches to understanding the motivations and expectations of traditional farmers in the maintenance of biodiversity zones in the Andes. Management of Environmental Quality 22 (2): 213–232. https://doi.org/10.1108/14777831111113392.

Giunta, I. 2014. Food sovereignty in Ecuador: Peasant struggles and the challenge of institutionalization. Journal of Peasant Studies 41: 1201–1224. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2014.938057.

Gliessman, S. 2002. Agroecología: Procesos Ecológicos en Agricultura Sostenible. Turrialba: CATIE.

González, V., J. Barkmann, and R. Marggraf. 2010. Social Network effects on the adoption of agroforestry species: Preliminary results of a study on differences on adoption patterns in southern ecuador. Procedias 4: 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.484.

Gray, C. 2009. Rural out-migration and smallholder agriculture in the southern Ecuadorian Andes. Population and Environment 30 (4–5): 193–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-009-0081-5.

Gyau, A., S. Franzel, M. Chiatoh, G. Nimino, and K. Owusu. 2014. Collective action to improve market access for smallholder producers of agroforestry products: Key lessons learned with insights from Cameroon’s experience. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustinability 6: 68–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2013.10.017.

Herforth, A. 2010. Promotion of Traditional african vegetables in Kenya and Tanzania: A case study of an intervention representing emerging imperatives in global nutrition. New York, USA: Cornell University.

Hellin, J., M. Lundy, and M. Meijer. 2009. Farmer organization, collective action and market access in Meso-America. Food Policy 34: 16–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2008.10.003.

Hermann, M., K. Amaya, L. Latournerie, and L. Castiñeiras. 2009. ¿Cómo Conservan Los Agricultores Sus Semillas en el Trópico Húmedo de Cuba, México y Perú? Roma, Italia: Bioversity International.

Howard, P.L. 2003. Women and plants: Gender relations in biodiversity management and conservation. London: Zed Books.

Instituto Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología (INAMHI). 2014a. Análisis de Las Condiciones Climáticas Registradas en el Ecuador Continental en el Año 2013 y su Impacto en el Sector Agrícola. Quito, Ecuador.

Instituto Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología (INAMHI). 2014b. Boletín Climatológico Anual 2013. Quito, Ecuador.

Instituto Nacional Estádistica y Censos (INEC). 2010. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2010. http://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/sistema-integrado-de-consultas-redatam/.

Instituto Nacional del Patrimonio Cultural (INPC). 2012. Memoria Oral del Pueblo Saraguro. Loja, Ecuador: Regional 7 Instituto Nacional de Patrimonio Cultural.

Isaac, M. 2012. Agricultural information exchange and organizational ties: The effect of network topology on managing agrodiversity. Agricultural Systems 109: 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2012.01.011.

Intriago, R., R. Gortaire Amézcua, E. Bravo, and C. O’Connell. 2017. Agroecology in ecuador: Historical processes, achievements, and challenges. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems. 41 (3–4): 311–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2017.1284174.

Jones, A., A. Shrinivas, and R. Bezner-Kerr. 2014. Farm production diversity is associated with greater household dietary diversity in Malawi: findings from nationally representative data. Food Policy 46 (June): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.02.001.

Kasem, S., and G. Thapa. 2011. Crop diversification in Thailand: Status, determinants, and effects on income and use of inputs. Land Use Policy 28: 618–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2010.12.001.

Katz, E. 2003. The Changing Role of Women in the Rural Economies of Latin America. In: Current and Emerging Issues for Economic Analysis and Policy Research. Volume I: Latin America and the Caribbean, edited by B. Davis, 31–66. Rome, Italy: FAO.

Kennedy, G., T. Ballard, and MC. Dop. 2013. Guidelines for Measuring Household and Individual Dietary Diversity. Roma: FAO. Accessed on 10th February 2022 https://www.fao.org/publications/card/es/c/5aacbe39-068f-513b-b17d-1d92959654ea/

Kristjanson, P., A. Krishna, M. Radeny, and J. Kuan. 2007. Poverty dynamics and the role of livestock in the Peruvian Andes. Agricultural Systems 94: 294–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2006.09.009.

Kumar, A., K. Pramod, and A. Sharma. 2012. Crop diversification in Eastern India: Status and determinants. Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics 67: 600–616. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.204840.

La Vía Campesina. 2009. La Vía Campesina policy documents: 5th conference, Mozambique, 16th to 23rd October 2008. International Operational Secretariat of La Via Campesina. Accessed on 10th February 2022 at https://viacampesina.org/en/la-via-campesina-policy-documents/

Leps, J., and P. Smilauer. 2003. Multivariate analysis of ecological data using CANOCO. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Loconto, A., and M. Hatanaka. 2018. Participatory guarantee systems: Alternative ways of defining, measuring, and assessing ‘Sustainability.’ Sociologia Ruralis 58 (2): 412–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12187.

Ministerio de Agricultura y ganadería (MAGAP). 2012. Creación de Sellos de Calidad para Productos de Pequeños Productores. Quito, Ecuador.

Major, J., Ch. Clement, and A. DiTommaso. 2005. Influence of market orientation on food plant diversity of farms located on amazonian dark earth in the region of Manaus, Amazonas Brazil. Economic Botany 59 (1): 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1663/0013-0001(2005)059[0077:IOMOOF]2.0.CO;2.

Marchetta, F. 2013. Migration and nonfarm activities as income diversification strategies: The case of Northern Ghana. Canadian Journal of Development Studies 34: 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02255189.2013.755916.

Marshall, G.R. 2015. A social-ecological systems framework for food systems research: Accommodating transformation systems and their products. International Journal of the Commons 9 (2): 881–908.

Martínez, L. 1996. Familia Indígena: Cambios Socio Demográficos y Económicos. Quito, Ecuador: CONADE/FNUAP.

Martínez, L. 1998. Comunidades y Tierra en el Ecuador, 173–188. Quito: Ecuador Debate.

Martínez, L. 2002. Economía Política de Las Comunidades Indígenas. Quito, Ecuador: Abya-Yala.

Martínez, L. 2005. Migración Internacional y Mercado de Trabajo Rural en Ecuador. In La Migración Ecuatoriana Transnacionalismo, Redes e Identidades, ed. G. Herrera, M. Carrillo, and A. Torres, 147–168. Quito, Ecuador: FLACSO-Sede Ecuador.

Martínez-Torres, M.H., and P. Rosset. 2014. Diálogo de Saberes in La Vía Campesina: Food Sovereignty and Agroecology. The Journal of Peasant Studies 41 (6): 979–997. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2013.872632.

MBS-SSDR/IFAD/IICA. 1991. Saraguro - Yacuambi - Loja Rural Development Project Ecuador. Quito, Ecuador: IICA.

McMichael, Ph. 2011. Food system sustainability: Questions of environmental governance in the new world (dis)order. Global Environmental Change 21 (3): 804–812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.03.016.

McCune, N., J. Reardon, and P. Rosset. 2014. Agroecological formación in rural social movements. Radical Teacher 98: 31–37. https://doi.org/10.5195/rt.2014.71.

McGinnis, M. 2011. An introduction to IAD and the language of the Ostrom workshop: A simple guide to a complex framework. Policy Studies Journal 39 (1): 169–183.

McGinnis, M., and E. Ostrom. 2014. Social-ecological system framework: Initial changes and continuing challenges. Ecology and Society 19 (2): 30. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-06387-190230.

Meinzen-Dick, R., J. Behrman, L. Pandolfelli, A. Peterman, and A. Quisumbing. 2014. Gender and social capital for agricultural development. In Gender in agriculture, ed. A. Quisumbing, R. Meinzen-Dick, T. Raney, A. Croppenstedt, J. Behrman, and A. Peterman, 235–266. Netherlands: Springer.

Minot, N., M. Epprecht, TT. Anh, and LeQ. Trung. 2006. Income Diversification and Poverty in the Northern Uplands of Vietnam. Research Report of the International Food Policy Research Institute. Research Report 145. Washington, D.C., USA: International Food Policy Research Institute.

Neill, D.A., and P.M. Jørgensen. 1999. Climates. In Catalogue of the Vascular Plants of Ecuador, ed. Peter M. Jørgensen and Susana León-Yánez, 8–13. St. Louis, USA: Missouri Botanical Garden.

Nyéléni Movement for Food Sovereignty. 2015. Declaration of the international forum for agroecology. Nyeleni Forum for Food Sovereignty. Accessed 10th February , 2022. https://www.foodsovereignty.org/forum-agroecology-nyeleni-2015-2/declaration-of-the-international-forum-for-agroecology-nyeleni-2015/

Nsoso, S.J., M. Monkhei, and B.E. Tlhwaafalo. 2004. A survey of traditional small stock farmers in Molelopole North, Kweneng district, Botswana: Demographic parameters, market practices and marketing channels. Livestock Research for Rural Development. 16: 100.

Oksanen, J. 2013. Multivariate Analysis of Ecological Communities in R: Vegan Tutorial.

Oksanen, J., F. Guillem Blanchet, R. Kindt, P. Legendre, R. G. O’Hara, G. Leslie Simpson, Peter Solymos, H. Stevens, and H. Wagner. 2015. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R Package Version 3.2.2. http://cran.r-project.org/package=vegan. Accessed 10 Feb 2022

Ordoñez Sotomayor, A., and P. Ochoa Cueva. 2020. Ambiente, sociedad y turismo comunitario: La etnia Saraguro en Loja – Ecuador. Revista De Ciencias Sociales 26 (2): 180–191.

Ortega-Cerdà, M., and M.G. Rivera-Ferre. 2010. Indicadores Internacionales de Soberanía Alimentaria: Nuevas Herramientas para una Nueva Agricultura. Revista Iberoamericana De Economía Ecológica 14: 53–77.

Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the commons. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ostrom, E. 2009. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 325 (5939): 419–422. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1172133.

Ostrom, E., and T.K. Ahn. 2003. Una Perspectiva del Capital Social Desde Las Ciencias Sociales: Capital Social y Acción Colectiva. Revista Mexicana De Sociología 65 (1): 155–233.

Ostrom, E., and M. Cox. 2010. Moving beyond panaceas: A multi-tiered diagnostic approach for social-ecological analysis. Environmental Conservation 37 (04): 451–463. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892910000834.

Oteros-Rozas, E., F. Ravera, and M. García-Llorente. 2019. How does agroecology contribute to the transitions towards social-ecological sustainability? Sustainability 11: 4372. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164372.

Oyarzun, P., R. Borja, S. Sherwood, and V. Parra. 2013. Making sense of agro-biodiversity, diet, and intensification of smallholder family farming in the highland Andes of Ecuador. Ecology of Food and Nutrition 52 (6): 515–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/03670244.2013.769099.

Patel, R. 2012. Food sovereignty: Power, gender, and the right to food. PLoS Medicine 9: e1001223. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001223.

Pelletier, D.L., V. Kraak, Ch. McCullum, U. Unsitalo, and R. Rich. 1999. Community food security: Salience and participation at community level. Agriculture and Human Values 16: 401–419.

Perreault, Th. 2003. Making space: Community organization, agrarian change, and the politics of scale in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Latin American Perspectives 30 (1): 96–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X02239146.

Pfeiffer, L., A. López-Feldman, and J.E. Taylor. 2009. Is off-farm income reforming the farm? Evidence from Mexico. Agricultural Economics 40 (2): 125–138. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2009.00365.x.

Pohle, P., A. Gerique, M. Park, and M. F. L. Sandoval. 2010. Human Ecological Dimensions in Sustainable Utilization and Conservation of Tropical Mountain Rain Forests under Global Change in Southern Ecuador. In Tropical Rainforests and Agroforests under Global Change, edited by T. Tscharntke, C. Leuschner, E. Veldkamp, H. Faust, E. Guhardja, and A. Bidin, 477–509. Environmental Science and Engineering. Berlin: Springer

Pretty, J., and D. Smith. 2004. Social capital in biodiversity conservation and management. Conservation Biology 18 (3): 631–638. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.00126.x.

Proaño, V., and P. Lacroix. 2013. Dinámicas de Comercialización para la Agricultura Familiar Campesina: Desafíos y Alternativas en el Escenario Ecuatoriano. Ed. Verónica Proaño and Pierril Lacroix. Quito: SIPAE.

Prosperi, P., Th. Allen, B. Cogill, M. Padilla, and I. Peri. 2016. Towards metrics of sustainable food systems: A review of the resilience and vulnerability literature. Environmental System and Decisions 36: 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10669-016-9584-7.

Reardon, Th., J. Berdegué, and G. Escobar. 2001. Rural nonfarm employment and incomes in Latin America: overview and policy implications. World Development 29 (3): 395–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00112-1.

Rosero, F., Y.C. Yonfá, and F. Regalado. 2011. Soberanía alimentaria, modelos de desarrollo y tierras en Ecuador. Quito: CAFOLIS.

Rosset, P., B. Sosa, A. Jaime, and D. Lozano. 2011. The campesino-to-campesino agroecology movement of ANAP in cuba: social process methodology in the construction of sustainable peasant agriculture and food sovereignty. Journal of Peasant Studies 38 (1): 161–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2010.538584.

Rosset, P., and M. Altieri. 2017. Agroecology: Science and politics; agrarian change and peasant studies. Black Point, NS, Canada: Fernwood Publishing Co LTD.

Rozelle, S., J.E. Taylor, and A. DeBrauw. 1999. Migration, remittances, and agricultural productivity in China. American Economic Review 89 (2): 287–291. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.89.2.287.

Ruíz-Almeida, A., and M.G. Rivera-Ferre. 2019. Internationally-based indicators to measure agri-food systems sustainability using food sovereignty as a conceptual framework. Food Security 11 (6): 1321–1337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-019-00964-5.

Sherwood, S., A. Arce, P. Berti, R. Borja, P. Oyarzun, and E. Bekkering. 2013. Tackling the new materialities: Modern food and counter-movements in ecuador. Food Policy 41: 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2013.03.002.

Schreinemachers, P., M.A. Patalagsa, Md. Rafiqul Islam, Md. Nasir Uddin, S. Sh Ahmad, Md. Chandra Biswas, R.-Y. Tanvir Ahmed, P. Yang, B.. S. Hanson, and C. Takagi. 2015. The effect of women’s home gardens on vegetable production and consumption in Bangladesh. Food Security 7: 97–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-014-0408-7.

Sichoongwe, K., L. Mapemba, G. Tembo, and D. Ng’ong’ola,. 2014. The determinants and extent of crop diversification among smallholder farmers: A case study of southern province Zambia. Journal Agricultural Science 6: 150–159. https://doi.org/10.5539/jas.v6n11p150.

Simoncini, R. 2015. Introducing territorial and historical contexts and critical thresholds in the analysis of conservation of agro-biodiversity by alternative food networks, in Tuscany, Italy. Land Use Policy 42: 355–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.08.010.

Sistema Información Nacional Agricultura, Ganadería, Acuacultura y Pesca (SINAGAP). 2000. III Censo Nacional Agropecuario. Quito.

Steins, N.A., and V.M. Edwards. 1999. Platforms for collective action in multiple-use common-pool resources. Agriculture and Human Values 16: 241–255.

Tegebu, F.N., E. Mathijs, J. Deckers, M. Haile, J. Nyssen, and E. Tollens. 2012. Rural livestock asset portfolio in northern Ethiopia: A microeconomic analysis of choice and accumulation. Tropical Animal Health and Production 44: 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-011-9900-7.

Thompson, J., and I. Scoones. 2009. Addressing the dynamics of agri-food systems: An emerging agenda for social science research. Environmental Science and Policy 12 (4): 386–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2009.03.001.

Trinh, L.N., J.W. Watson, N.N. De, N.V. Minh, P. Chu, B.R. Sthapit, and P.B. Eyzaguirre. 2003. Agro-biodiversity conservation and development in Vietnamese home gardens. Agriculture Ecosystem and Environment 97: 317–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-8809(02)00228-1.

Twyman, J., P. Useche, and C.D. Deere. 2015. Gendered perceptions of land ownership and agricultural decision-making in ecuador: Who are the farm managers? Land Economics 91: 479–500. https://doi.org/10.3368/le.91.3.479.

Vallejo-Rojas, V., F. Ravera, and M.G. Rivera-Ferre. 2015. Developing an integrated framework to assess agri-food systems and its application in the Ecuadorian Andes. Regional Environmental Change. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-015-0887-x.

Vanwey, L., and T. Vithayathil. 2013. Off-farm work among rural households: a case study in the Brazilian Amazon. Rural Sociology 78 (1): 29–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1549-0831.2012.00094.x.

Velásquez-Milla, D., A. Casas, J. Torres-Guevara, and A. Cruz-Soriano. 2011. Ecological and socio-cultural factors influencing in situ conservation of crop diversity by traditional Andean households in Peru. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 7 (1): 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-7-40.

von Braun, J. 1995. Agricultural commercialization: Impacts on income and nutrition and implications for policy. Food Policy 20 (3): 187–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-9192(95)00013-5.

Walsh-Dilley, M. 2012. Indigenous reciprocity and globalization in rural Bolivia. Grassroots Development 33: 58–61.

Williams, L., J. Germov, S. Fuller, and M. Freij. 2015. A Taste of ethical consumption at a slow food festival. Appetite 91: 321–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.04.066.

Winkel, T., L. Núñez-Carrasco, J. Cruz Pablo, N. Egan, L. Sáez-Tonacca, P. Cubillos-Celis, C. Poblete-Olivera, N. Zavalla-Nanco, B. Miño-Baes, and M.-P. Viedma-Araya. 2020. Mobilising common biocultural heritage for the socioeconomic inclusion of small farmers: Panarchy of two case studies on quinoa in Chile and Bolivia. Agriculture and Human Values 37: 433–447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-019-09996-1.

Winters, P., R. Cavatassi, and L. Lipper. 2006. Sowing the seeds of social relations: the role of social capital in crop diversity. Rome, Italy: FAO.

Winters, P., B. Davis, and L. Corral. 2002. Assets, activities and income generation in rural Mexico: factoring in social and public capital. Rome, Italy: FAO.

Wittman, H. 2011. Food sovereignty: A new rights framework for food and nature? Environment and Society 2 (1): 87–105. https://doi.org/10.3167/ares.2011.020106.

Zuur, A., E. Ieno, and C. Elphick. 2010. A protocol for data exploration to avoid common statistical problems. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 1 (1): 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210X.2009.00001.x.

Acknowledgements

We thank Narcisa Medina and Rovin Andrade, local leaders of the rural Andean parishes Jimbilla and San Lucas of the Loja canton; and, Nancy Huaca, coordinator of the Agroecological Network of Loja (RAL); who have shown their aperture for carrying out the research in eight communities of their locality and have shared their experiences and knowledges. This research was part of a PhD study funded by the National Secretariat for Science, Technology and Innovation (SENESCYT) of Ecuadorian government. The corresponding author has been funded by AXA Research Fund (2016) and Ramón i Cajal fellowship (RYC2018-025958-I) funded by Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (Spain).

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vallejo-Rojas, V., Rivera-Ferre, M.G. & Ravera, F. The agri-food system (re)configuration: the case study of an agroecological network in the Ecuadorian Andes. Agric Hum Values 39, 1301–1327 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-022-10318-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-022-10318-1