Abstract

Rheumatic autoimmune diseases are associated with a myriad of comorbidities. Of particular importance due to their morbimortality are cardiovascular diseases. COVID-19 greatly impacted the world population in many different areas. Patients with rheumatic diseases had to face changes in their healthcare, in addition to unemployment, a decrease in physical activity, social isolation, and lack of access to certain medications. This review summarizes the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on cardiovascular risk factors, comorbidities, and unhealthy behaviors in patients with rheumatic inflammatory autoimmune diseases, particularly focused on rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Searches were carried out in MEDLINE/PubMed and Scopus from August to December 2022. Four reviewers screened the title and abstract of retrieved records. Potentially eligible reports were then reviewed in full text. Differences were reconciled by either consensus or discussion with an external reviewer. During the COVID-19 pandemic, patients with rheumatic diseases showed an increase in the prevalence of mental health disorders (43.2–57.7%), reduced physical activity (56.8%), and a worsening in eating behaviors. Alcohol intake increased (18.2%), especially in early phases of the pandemic. Smoking prevalence decreased (28.2%). Dyslipidemia and hypertension showed no changes. The pandemic and lockdown affected rheumatic patients not only in disease-related characteristics but in the prevalence of their cardiovascular comorbidities and risk factors. Lifestyle changes, such as healthy eating, physical activity, and optimal management of their rheumatic diseases and comorbidities, are essential to manage the long-lasting consequences of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Key Points • During the COVID-19 pandemic, anxiety, depression, sedentarism, obesity, and a worsening in eating behaviors increased. •Patients with rheumatic diseases and comorbidities have worse clinical outcomes and a higher cardiovascular disease burden than those without them. •Comparative studies are necessary to precisely elucidate the pandemic’s impact on the prevalence of cardiovascular disease, risk factors, and comorbidities in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

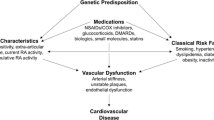

Rheumatic autoimmune diseases are associated with a myriad of comorbidities [1]. Ischemic heart disease, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, and peripheral arterial disease are important due to their morbimortality [2]. Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) entails an increased prevalence of cardiovascular traditional risk factors, including hypertension, diabetes, smoking, obesity, and dyslipidemia [3]. Additionally, the risk of ischemic heart disease is 5- to eightfold higher in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and 2- to threefold higher in RA than in the general population [4, 5].

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic greatly impacted the world population in many aspects, including personal relationships, work, education, and health. Isolation, quarantine, and the home office impacted lifestyle, becoming a public health challenge [6] with these strategies increasing sitting and screen time [7]. Mental health disorders, such as major depression and anxiety, also increased. The most affected populations were women and young people [8]. The greater increase among females was anticipated because women were more likely affected by the social and economic consequences of the pandemic [9].

Patients with rheumatic autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus, had to face several additional challenges besides COVID-19 infection. These people suffered changes in their medical care, from the availability of qualified rheumatologists to a telemedicine implementation. Unemployment, decreased physical activity, social isolation, and a lack of access to certain medications, including hydroxychloroquine, were other issues they faced [10].

Social isolation measurements applied in many countries have influenced rheumatic patients’ health. A decrease in physical activity predisposes an increase in disease activity and flares [11, 12]. Isolation from family and friends could mean denying patient’s emotional support, increasing the risk of depression and anxiety [13], and unhealthy eating behaviors, such as increased snacking and consumption of comfort foods [14,15,16]. At the same time, these actions could lead to an increase in their body weight, and therefore, overweight and obesity. This review summarizes the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities in patients with rheumatic autoimmune diseases (Table 1). Since there is a lack of data about changes in comorbidities during the lockdown, we focused on the most relevant of these, for which there is more information, RA and SLE.

Methods

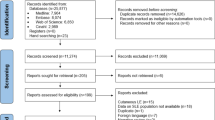

A review of the literature was conducted analyzing the published data about cardiovascular health and its changes in patients with autoimmune rheumatological diseases (particularly RA and SLE) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Eligibility criteria

It was included articles that contained information on risk factors and comorbidities in general population and patients with rheumatologic diseases before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, in addition to articles that report definitions. It was excluded those did not have information on risk factors and comorbidities of our interest.

Search strategies

Searches on the impact of comorbidities in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus were carried out in MEDLINE/PubMed and Scopus from August to December 2022. The keywords used for the search were “rheumatoid arthritis” and “systemic lupus erythematosus” in combination with other keywords such as “COVID-19,” “lockdown,” “comorbidities,” “cardiovascular risk factors,” “pandemic,” “diabetes,” “hypertension,” “dyslipidemia,” “alcohol intake,” “obesity,” “sedentarism,” “diet,” “depression,” “anxiety,” and “smoking.”

Study selection

Four reviewers screened the title and abstract of retrieved records. Potentially eligible reports were then reviewed in full text. Differences were reconciled by either consensus or discussion with an external reviewer.

Risk factors and unhealthy behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic

Sedentarism

Physical activity (PA) is defined as any bodily movement produced by the skeletal muscles that result in energy expenditure above resting (basal) levels [26]. An increase in PA is an intervention that can significantly improve many different disease-related symptoms such as fatigue, functional disability, inflammation, and systemic outcomes (cardiovascular disease risk and body composition) [27]. PA has health benefits for people with rheumatic diseases, and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) recommends exercises in the four domains (cardiorespiratory fitness, muscle strength, flexibility, and neuromotor performance) [28]. In one study, it was shown that after 24 weeks of exercise, subjects had better total cholesterol and triglyceride levels, decreased fat tissue and blood pressure, lower serum levels of proinflammatory C reactive protein (CRP), and higher levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) [29]. The COVID-19 pandemic caused many lifestyle changes in the population with chronic health conditions [30], including rheumatic diseases. In addition, the reduction in PA led patients to increased sarcopenia and the deterioration of muscle strength and function more frequently in older populations [31]. During the pandemic, PA was reduced by as much as 56.8%, mostly due to fear of infection, as reported by Saxena et al., and thus, quality of life and disease activity were affected [32].

Researchers around the world have reported sedentary behavior findings during the quarantine. In France, Deschasaux-Tanguy et al. reported that 63.2% of the participants increased sedentary time with an average of 7 h per day spent sitting [33] similar to a study in Europe, North Africa, Western Asia, and the Americas, where the most notable change in the population was a 28.6% increase in the hours per day sitting [34], mostly increased screen time [35], especially TV-viewing. In a comparison of pre-COVID-19 and during the COVID-19 pandemic, people spending more than 5 h per day in front of a screen increased from 14.6 to 37.5%, respectively [36]. PA in patients with RA and SLE is less frequent due to the discomfort caused at the beginning of exercise, even considering the previously described benefits.

Alcohol

A systematic review showed that alcohol drinking remained stable in most of the population examined. However, an important part of the sample increased consumption during the early stages of the pandemic, with a decreasing trend at the end of the lockdown [37]. Those motivated to drink alcohol to cope had a greater increase in consumption [38]. In the same way, a cross-sectional study conducted in seven European countries with 1800 patients with rheumatic diseases (REUMAVID study) showed that most drank the same amount of alcohol. Still, a significant percentage (18.2%) increased their consumption [17].

Consequences of alcohol abuse include increased cardiovascular risk (CVR) and liver disease. It also influences the innate and adaptative immune system. In RA, it is important to consider that alcohol consumption increases the risk of developing a liver injury induced by treatment with methotrexate (MTX). Alcohol added to folate deficiency, the administration of other hepatotoxic drugs and lipid disorders predispose to MTX-induced steatohepatitis and hepatic fibrosis [39]. Several observational studies have investigated the potential relationship between alcohol intake and the risk of rheumatic diseases. One suggested that ethanol and antioxidants in alcohol could suppress the immune response and trigger proinflammatory cytokines, which may play an important role in the risk of RA or SLE [40]. Other emerging studies associate moderate alcohol consumption with protection against both diseases [41, 42]. Nevertheless, the beneficial effects of alcohol have been questioned due to the difficulties in establishing a safe drinking threshold [43].

Smoking

It is well known that smoking negatively affects several disease outcomes of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs), such as the response to treatment, disease activity, and comorbidities. Tobacco consumption in patients with RA causes a lower response to a first-line disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD), a greater probability of interstitial lung disease before or after DMARDs, a 2.6-higher risk of EULAR non-remission, higher disease activity, and higher CRP levels compared to non-smokers. SLE patients who smoke have worse 36-Item Short form survey scores and a more severe rash [44]. The REUMAVID study showed that smoking declined in patients with RMDs as 28.2% of the population quit smoking during the pandemic; however, a significant proportion of patients (24.6%) smoked more than before COVID-19 pandemic [17]. Also, in a study made from the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance database, patients with RMDs who smoked were more likely to be admitted to hospital, and ever smoking was more common in those who died [18].

Dietary changes

There is evidence of the association between diet, both micro- and macronutrients, and immunity regulation and how disturbances in the nutritional status of people can lead to autoimmunity [45]. The COVID-19 pandemic had many, mainly, negative consequences on feeding and dietary habits and could have an important impact on health, including mental health. Most studies reported negative dietary changes, especially an increase in meals and snacks. A possible explanation could be increased intake and consumption of high-caloric foods to cope with anxiety, sadness, and boredom during lockdown [14, 15, 46,47,48,49].

Some specific dietary behavior could be associated with gender. Boaz et al. reported women consumed sweet baked goods, vegetables, and olive oil more than men. On the other hand, men consumed red meat and sweetened/carbonated beverages more than women [46]. Most of the information about dietary changes was obtained from studies on the general population. Caton et al. found similar outcomes in patients with rheumatic diseases. Most of these patients declared a worsening in their diet during the lockdown. This finding was explained by an increase in the number of meals and caloric intake, as well as adopting this behavior for emotional coping [16].

Comorbidities during the COVID-19 pandemic

Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes is a very important comorbidity to consider in patients with SLE or RA, increasing by itself the cardiovascular risk in this population, being the cardiovascular disease the main cause of death in people with diabetes mellitus [50].

Various studies carried out before the pandemic documented a prevalence of 15% in patients with RMD, which was reflected in studies carried out during the pandemic, where the prevalence of diabetes mellitus in patients with RA was 14.9% [19, 51], although in another study carried out in 2021, a prevalence of 25.02% was found in patients with rheumatological diseases, mainly RA and SLE [52]. These data could point to a slight increase in this comorbidity in patients with RA and SLE, although more studies are needed to clarify this potential increase.

Obesity

Obesity is prevalent in patients with rheumatic diseases, such as RA [53] and SLE [54]. Observational studies have shown that obesity predisposes to negative outcomes [55]. The negative influence of an excessively high body mass index (BMI) on the risk of developing the disease, on activity indexes, quality of life, and response to treatment is suggested to be strong in inflammatory joint diseases (IJD), such as RA and SLE [56, 57], because of increased cytokine production in visceral adipose tissue [55].

During the COVID-19 outbreak, some studies used weight modifications as an indicator of habit changes [35, 57,58,59,60,61] that could lead to an increase in obesity [35]. Patients that are overweight or obese, in addition to having longstanding and moderate disease activity, have a high risk of cardiovascular disease [53]. Thus, this risk may increase in patients with rheumatic diseases because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Hypertension

One of the most common comorbidities in severe COVID-19 patients is hypertension, which is also a risk factor for pneumonia and severe disease in the general population and patients with multiple comorbidities, including rheumatic diseases [20, 62,63,64]. Therefore, blood pressure follow-up during the lockdown was an important point for public health services. In a sample of 72 hypertensive patients, Fucile et al. demonstrated a decrease in blood pressure levels, approximately 7 mmHg in systolic blood pressure and 3 mmHg in diastolic blood pressure [65]. Almost the same results were found in the study by Pengo et al., in which they reported a decrease in blood pressure in 126 patients with a reduction of 6 mmHg in systolic blood pressure in most patients during the first lockdown period [66]. Similar results were found in a French population, with a reduction of about 1.5 mmHg in diastolic blood pressure and 3 mmHg in systolic pressure after 4 weeks of lockdown [67]. However, these changes in blood pressure did not last beyond the first period of lockdown, according to the blood pressure values recorded between January and March 2021, where there was a slight increase in diastolic and systolic blood pressure values [68]. Although there is insufficient evidence of this behavior in rheumatic patients, the worsening lifestyle in the general population might be similar in rheumatic patients, with a tendency for increased blood pressure.

Hypertension among rheumatic patients hospitalized for COVID-19 was around 50%, and this finding correlated with a higher probability of being admitted than rheumatic patients who do not have hypertension [69,70,71,72]. Also, hypertension in this population is an independent determinant of disease severity, increasing mortality risk [64].

In the rheumatic population, an interesting finding was observed by Fouad et al., where most patients with rheumatic diseases and comorbidities such as hypertension dropped their medication or did not adhere to treatment because of the fear generated by COVID-19. They also reported that close to 50% of the rheumatologic patients (mainly RA and SLE) experienced limitations in access to specialized care including DMARDs during this period. Besides, they found a negative impact in mental health in 92% of their patients with 60% of high levels of psychological distress and an increase in patients with uncontrolled disease from 8.3% prior to the pandemic to 20% during it [62].

Pham et al. found that patients with higher values of the 4-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4) have higher values of Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3 (RAPID3) score. During the pandemic, most of the patients included in the study presented higher PSS-4 values [73]. Considering the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health mentioned before, the increase in uncontrolled disease, and the correlation found by Pham et al., there is clearly a negative impact on disease activity caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, and derived actions. These findings take importance mainly because of the high prevalence of hypertension among patients with RA. This drop in medication and the high prevalence in psychological distress worsen their cardiovascular risk, increase disease activity, and eventually lead to a major risk of being admitted when infected with SARS-CoV-2 [64, 74].

Dyslipidemia

Dyslipidemia is an important comorbidity among patients with rheumatic diseases mainly because of its role in subclinical atherosclerosis development, increasing the cardiovascular risk and the prevalence of carotid plaque [75, 76]. Although there is a lack of evidence about the behavior of blood lipid levels during the pandemic, some studies showed a trend of increased blood lipid levels when comparing before and after the lockdown in asymptomatic patients [77]. Even patients with an optimal lipid profile before the pandemic were affected by the lockdown. Perrone et al. found that stopping physical activity correlated with an increase of 15.8% in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and total cholesterol [78, 79]. This behavior in the lipid profile might have also affected patients with RA and SLE due to the stopping of physical activity because of the pandemic, COVID-19, and the dropping of medication mentioned before. This finding is relevant because most people with rheumatic diseases and severe COVID-19 are older than 65 and have a high rate of comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia [64]. In addition, higher blood lipid levels correlate with a worse prognosis in rheumatic patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and with a higher risk of hospitalization than rheumatic patients who do not have dyslipidemia [63, 64, 71, 80, 81].

Due to the prothrombotic state caused by COVID-19 and accelerated atherosclerosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or systemic erythematosus lupus, dyslipidemia needs special attention from physicians, and further investigation about the interactions of SARS-CoV-2, rheumatic diseases, and dyslipidemia in this population might be necessary [82].

Depression and anxiety

Lockdown caused an increase in the prevalence of rheumatic patients with psychopathologies, especially depression and anxiety [12, 13, 21,22,23,24, 83, 84]. In the REUMAVID study, of the 534 RA patients included, 53.2% were at risk of anxiety and 43.2% of depression. Meanwhile, of 97 SLE patients included, 57.7% were at risk of anxiety and 51.5% of depression [17]. Fear of infection by SARS-CoV-2 and possible outcomes, familial health concerns, and baseline mental health have been described as possible risk factors for depression and anxiety [25, 83]. Scherlinger et al. reported that difficulties accessing medical care were significantly associated to anxiety (OR 1.94, p = 0.012); for depression, financial difficulties (OR 2.59, p = 0.006) and difficulties accessing medical care (OR 2.57, p < 0.0001) were associated [21]. On the other hand, emotional support and resilience have been mentioned as possible protective factors [13]. The study realized by Tee et al. found that satisfaction with the available health information COVID-19 was associated with depression subscales (p = 0.005) and wearing of face masks was associated with lower levels of depression (p = 0.044) [23].

The COVID-19 outbreak reduced activities and social interaction, which impacted mental health [11]. Depression and anxiety are highly prevalent in patients with rheumatic diseases [11, 85]. There are many reports about an increase in the frequency of flares in rheumatic patients associated with a decrease in physical activity levels, which predisposed to depression and anxiety. Inversely, patients suffering from these mental disorders are susceptible to increased disease activity scores [11, 12, 21, 25]. Ammitzbøll et al. found an increase of disease activity in 23.5% of patients, which contrasts with 18.9% of patients who showed symptoms of moderate depression in their study [12].

Depression and anxiety are twice as common in women, which is relevant since they represent a large proportion of rheumatic patients [86, 87]. Although depression and anxiety are not considered traditional cardiovascular risk factors, they have been related to increased cardiovascular events and worse outcomes [87, 88]. Possible mechanisms for this increase in cardiovascular risk are increased inflammatory cytokines, platelet aggregation, oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, atherosclerosis progression, and an increase in unhealthy behaviors such as smoking, decreased physical activity, and a higher intake of high-calorie foods associated with these mental disorders [87, 88].

Patients with cognitive impairment have a high prevalence of depression and anxiety, which increased during the lockdown [89, 90]. This data is relevant since the development of cognitive disturbances is common in patients with RA and SLE [91, 92]. Bartolini et al. observed a cognitive dysfunction prevalence of 38 to 71% in RA patients [93]. These findings, and the increased risk of depression and anxiety in RA and SLE, suggest that cognitive impairment could lead to worse cardiovascular outcomes.

Discussion

In this review, we found that during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was an increase in the prevalence of some of the most important cardiovascular comorbidities and risk factors in patients with rheumatic diseases. There was an increase in obesity and sedentarism, which can potentiate immune dysregulation and is linked with increased disease activity and symptoms in patients with RA [94]. When analyzing the impact of the pandemic on mental health, there was an increased prevalence of psychiatric disorders. Several studies associate RMDs, especially RA and SLE, with depression and anxiety. This finding is generally attributed to inflammation and the adverse impact of these diseases on quality of life, functioning, and productivity. Inversely, depression is linked to an increased risk of developing RA and a deteriorating disease course reflected in poor treatment adherence [95]. The effect of the pandemic on alcohol and tobacco consumption is difficult to determine. In general, a positive impact was seen by decreasing smoking prevalence and increasing the intention to quit smoking. As for alcoholism, an increase was reported, especially at the beginning of the pandemic, but it decreased and remained stable in the final phases. An increase in consumption was seen in both risk behaviors in those who used it as a coping mechanism. We must emphasize the importance of reducing these comorbidities, as smoking is considered the most important modifiable risk factor for RA. Alcohol consumption indirectly affects rheumatoid patients by interacting with some drugs used for the disease [39, 96].

It is important to know the behavior of these comorbidities during the pandemic in rheumatic and non-rheumatic patients due to the lack of access to healthcare services that were more available before the lockdown. There were also limited healthcare services for patients with hypertension and dyslipidemia, which also play an important role in rheumatic diseases due to the accelerated development of subclinical atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events [97]. These findings are interesting because most rheumatic patients with hypertension, dyslipidemia, and/or obesity hospitalized for COVID-19 had worse outcomes, such as severe disease or death [81, 98]. It is also important to mention that we need further investigation into the prevalence of these comorbidities in patients with rheumatic diseases due to a lack of information.

Analyzing all these consequences that the pandemic had on patients with rheumatic inflammatory autoimmune diseases, we also researched strategies to reduce comorbidities. The EULAR 2021 recommendations mention the importance of quitting tobacco use due to impaired function, increased symptoms, disease activity, disease progress, and comorbidities. In addition, this habit could affect DMARD treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Although a low level of alcohol consumption is unlikely to impact rheumatic disease outcomes negatively, people with rheumatoid arthritis and health professionals should be aware because moderate alcohol consumption is associated with an increased risk of rheumatoid arthritis flare and comorbidities. Sometimes, the line between low and moderate alcohol consumption is not well delimited due to misunderstanding or misinformation [99].

Physical activity benefits several aspects of physical and mental health and should be promoted for all. It has a protective effect on the development of depression or can be used to manage symptoms acutely [100]. In the long term, continuous exercise will modulate the immune system and decrease chronic inflammation, offering protection against infections and chronic diseases [29]. Physical activity, specifically aerobic exercise in moderate intensity for at least 150 min per week and strengthening exercise twice a week, has an anti-inflammatory effect that is beneficial in RA and SLE patients by reducing inflammatory markers and joint pain, as well as improving function and quality of life and reducing all-cause mortality in patients with rheumatic autoimmune diseases [99].

This study has limitations worth noting. Information on the behavior of cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities in patients with rheumatological diseases is limited. Additionally, disease activity data during and after the pandemic, which may impact cardiovascular risk, are also scarce. Studies that compare these factors longitudinally before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic are necessary.

Conclusion

The pandemic and lockdown by COVID-19 affected rheumatic patients, not only in disease-related characteristics but in the prevalence of their comorbidities, predisposing them to the development of new complications and, therefore, an increase in their cardiovascular risk. Lifestyle changes, such as healthy eating, and physical activity, besides optimal management of their rheumatic diseases and comorbidities, are essential to manage the consequences of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

References

Baillet A, Gossec L, Carmona L, de Wit M, van Eijk-Hustings Y, Bertheussen H, Alison K, Toft M, Kouloumas M, Ferreira RJO, Oliver S, Rubbert-Roth A, van Assen S, Dixon WG, Finckh A, Zink A, Kremer J, Kvien TK, Nurmohamed M, van der Heijde D, Dougados M (2016) Points to consider for reporting, screening for and preventing selected comorbidities in chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases in daily practice: a EULAR initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 75:965–973. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209233

Peters MJL, Symmons DPM, McCarey D, Dijkmans BAC, Nicola P, Kvien TK, McInnes IB, Haentzschel H, Gonzalez-Gay MA, Provan S, Semb A, Sidiropoulos P, Kitas G, Smulders YM, Soubrier M, Szekanecz Z, Sattar N, Nurmohamed MT (2010) EULAR evidence-based recommendations for cardiovascular risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 69:325–331. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2009.113696

Nurmohamed MT, Heslinga M, Kitas GD (2015) Cardiovascular comorbidity in rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol 11:693–704. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2015.112

Schieir O, Tosevski C, Glazier RH, Hogg-Johnson S, Badley EM (2017) Incident myocardial infarction associated with major types of arthritis in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 76:1396–1404. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210275

Santos MJ, Vinagre F, Canas Da Silva J, Gil V, Fonseca JE (2010) Cardiovascular risk profile in systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis: a comparative study of female patients. Acta Reumatol Port 35:325–332

Dempsey PC, Biddle SJH, Buman MP, Chastin S, Ekelund U, Friedenreich CM, Katzmarzyk PT, Leitzmann MF, Stamatakis E, van der Ploeg HP, Willumsen J, Bull F (2020) New global guidelines on sedentary behaviour and health for adults: broadening the behavioural targets. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 17:151. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-01044-0

Runacres A, Mackintosh KA, Knight RL, Sheeran L, Thatcher R, Shelley J, McNarry MA (2021) Impact of the covid-19 pandemic on sedentary time and behavior in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18:11286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111286

Santomauro DF, Mantilla Herrera AM, Shadid J, Zheng P, Ashbaugh C, Pigott DM, Abbafati C, Adolph C, Amlag JO, Aravkin AY, Bang-Jensen BL, Bertolacci GJ, Bloom SS, Castellano R, Castro E, Chakrabarti S, Chattopadhyay J, Cogen RM, Collins JK, Dai X, Dangel WJ, Dapper C, Deen A, Erickson M, Ewald SB, Flaxman AD, Frostad JJ, Fullman N, Giles JR, Giref AZ, Guo G, He J, Helak M, Hulland EN, Idrisov B, Lindstrom A, Linebarger E, Lotufo PA, Lozano R, Magistro B, Malta DC, Månsson JC, Marinho F, Mokdad AH, Monasta L, Naik P, Nomura S, O’Halloran JK, Ostroff SM, Pasovic M, Penberthy L, Reiner RC, Reinke G, Ribeiro ALP, Sholokhov A, Sorensen RJD, Varavikova E, Vo AT, Walcott R, Watson S, Wiysonge CS, Zigler B, Hay SI, Vos T, Murray CJL, Whiteford HA, Ferrari AJ (2021) Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 398:1700–1712. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7

Burki T (2020) Newsdesk The indirect impact of COVID-19 on women. Lancet Infect Dis 8:904–905. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30568-5

D’Silva KM, Wallace ZS (2021) COVID-19 and rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 33:255–261. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOR.0000000000000786

Bhatia A, Kc M, Gupta L (2021) Increased risk of mental health disorders in patients with RA during the COVID-19 pandemic: a possible surge and solutions. Rheumatol Int 41:843–850. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-021-04829-z

Ammitzbøll C, Andersen JB, Vils SR, Mistegaard CE, Mikkelsen S, Erikstrup C, Thomsen MK, Hauge E, Troldborg A (2021) Isolation, behavioral changes and low seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus or Rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 74:1780–1785. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.24716

Santos-Ruiz A, Montero-López E, Ortego-Centeno N, Peralta-Ramírez I (2021) Effect of COVID-19 confinement on the mental status of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Med Clin (Barc) 156:379–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2020.12.004

Bennett G, Young E, Butler I, Coe S (2021) The impact of lockdown during the COVID-19 outbreak on dietary habits in various population groups: a scoping review. Front Nutr 8:626432. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.626432

Antwi J, Appiah B, Oluwakuse B, Abu BAZ (2021) The nutrition-COVID-19 interplay: a review. Curr Nutr Rep 10:364–374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-021-00380-2

Caton E, Chaplin H, Carpenter L, Sweeney M, Tung HY, de Souza S, Galloway J, Nikiphorou E, Norton S (2021) The impact of COVID-19 on self-management behaviors and healthcare access for people with inflammatory arthritis. BMC Rheumatol 5:58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41927-021-00231-1

Garrido-Cumbrera M, Marzo-Ortega H, Christen L, Plazuelo-Ramos P, Webb D, Jacklin C, Irwin S, Grange L, Makri S, Frazão Mateus E, Mingolla S, Antonopoulou K, Sanz-Gómez S, Correa-Fernández J, Carmona L, Navarro-Compán V (2021) Assessment of impact of the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases in Europe: results from the REUMAVID study (phase 1). RMD Open 7:e001546. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001546

Conway R, Nikiphorou E, Demetriou CA, Low C, Leamy K, Ryan JG, Kavanagh R, Fraser AD, Carey JJ, Oonnell P, Flood RM, Mullan RH, Kane DJ, Ambrose N, Stafford F, Robinson PC, Liew JW, Grainger R, McCarthy GM (2022) Temporal trends in COVID-19 outcomes in people with rheumatic diseases in Ireland: data from the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance registry. Rheumatology (Oxford) 61:SI151–SI156. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keac142

Vicente GNS, Pereira IA, de Castro GRW, da Mota LMH, Carnieletto AP, de Souza DGS, da Gama FO, Santos ABV, de Albuquerque CP, Bértolo MB, Júnior PL, Giorgi RDN, RadominskiGuimarães SCMFBR, Bonfiglioli KR, de FátimaLobato da Cunha Sauma M, Brenol CV, da Rocha CastelarPinheiro G (2021) Cardiovascular risk comorbidities in rheumatoid arthritis patients and the use of anti-rheumatic drugs: a cross-sectional real-life study. Adv Rheumatol 61:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42358-021-00186-4

Fernández-Ávila DG, Barahona-Correa J, Romero-Alvernia D, Kowalski S, Sapag A, Cachafeiro-Vilar A, Meléndez B, Pastelín C, Palleiro D, Arrieta D, Reyes G, Pons-Estel GJ, Then-Báez J, Ugarte-Gil MF, Cardiel MH, Colman N, Chávez N, Burgos PI, Montufar R, Sandino S, Fuentes-Silva YJ, Soriano ER (2022) Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patients with rheumatic diseases in Latin America. Rheumatol Int 42:41–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-021-05014-y

Scherlinger M, Zein N, Gottenberg JE, Rivière M, Kleinmann JF, Sibilia J, Arnaud L (2022) Difficulties and psychological impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a nationwide patient association study. Healthcare (Switzerland). https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10020330

Itaya T, Torii M, Hashimoto M, Tanigawa K, Urai Y, Kinoshita A, Nin K, Jindai K, Watanabe R, Murata K, Murakami K, Tanaka M, Ito H, Matsuda S, Morinobu A (2021) Prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rheumatology (Oxford) 60:2023–2024. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keab065

Tee CA, Salido EO, Reyes PWC, Ho RC, Tee ML (2020) Psychological state and associated factors during the 2019 coronavirus disease (Covid-19) pandemic among filipinos with rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus. Open Access Rheumatol 12:215–222. https://doi.org/10.2147/OARRR.S269889

Wańkowicz P, Szylińska A, Rotter I (2021) Insomnia, anxiety, and depression symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic may depend on the pre-existent health status rather than the profession. Brain Sci 11(8):1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11081001

Johnstone G, Treharne GJ, Fletcher BD, Lamar RSM, White D, Harrison A, Stebbings S (2021) Mental health and quality of life for people with rheumatoid arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis in Aotearoa New Zealand following the COVID-19 national lockdown. Rheumatol Int 41:1763–1772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-021-04952-x

Siscovick DS, Laporte RE, Newman J, Health ; Iverson DC, Fielding JE (1985) Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research synopsis. Public Health Rep 100:126-131

Metsios GS, Stavropoulos-Kalinoglou A, Treharne GJ, Nevill AM, Sandoo A, Panoulas VF, Toms TE, Koutedakis Y, Kitas GD (2011) Disease activity and low physical activity associate with number of hospital admissions and length of hospitalisation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 13:R108. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar3390

Rausch Osthoff AK, Niedermann K, Braun J, Adams J, Brodin N, Dagfinrud H, Duruoz T, Esbensen BA, Günther KP, Hurkmans E, Juhl CB, Kennedy N, Kiltz U, Knittle K, Nurmohamed M, Pais S, Severijns G, Swinnen TW, Pitsillidou IA, Warburton L, Yankov Z, Vliet Vlieland TPM (2018) 2018 EULAR recommendations for physical activity in people with inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 77:1251–1260

Filgueira TO, Castoldi A, Santos LER, de Amorim GJ, de Sousa Fernandes MS, de Lima do NascimentoAnastácio W, Campos EZ, Santos TM, Souto FO (2021) The relevance of a physical active lifestyle and physical fitness on immune defense: mitigating disease burden, with focus on COVID-19 consequences. Front Immunol 5:12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.587146

Carter SJ, Baranauskas MN, Fly AD (2020) Considerations for Obesity, Vitamin D, and Physical Activity Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic. Obesity 28:1176–1177. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22838

Kirwan R, McCullough D, Butler T, Perez de Heredia F, Davies IG, Stewart C (2020) Sarcopenia during COVID-19 lockdown restrictions: long-term health effects of short-term muscle loss. GeroScience 42:1547–1578. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-020-00272-3

Saxena-Beem S, Dickson TA, Englund TR, Cleveland RJ, McCormick EM, Santana AE, Walker JA, Allen KD, Sheikh SZ (2022) Perceived Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical Activity Among Adult Patients With Rheumatological Disease. Open Rheumatol J 0:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr2.11507

Deschasaux-Tanguy M, Druesne-Pecollo N, Esseddik Y, de Edelenyi FS, Allès B, Andreeva VA, Baudry J, Charreire H, Deschamps V, Egnell M, Fezeu LK, Galan P, Julia C, Kesse-Guyot E, Latino-Martel P, Oppert JM, Péneau S, Verdot C, Hercberg S, Touvier M (2021) Diet and physical activity during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) lockdown (March-May 2020): results from the French NutriNet-Santé cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr 113:924–938. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa336

Ammar A, Brach M, Trabelsi K, Chtourou H, Boukhris O, Masmoudi L, Bouaziz B, Bentlage E, How D, Ahmed M, Müller P, Müller N, Aloui A, Hammouda O, Paineiras-Domingos LL, Braakman-Jansen A, Wrede C, Bastoni S, Pernambuco CS, Mataruna L, Taheri M, Irandoust K, Khacharem A, Bragazzi NL, Chamari K, Glenn JM, Bott NT, Gargouri F, Chaari L, Batatia H, Ali GM, Abdelkarim O, Jarraya M, el Abed K, Souissi N, van Gemert-Pijnen L, Riemann BL, Riemann L, Moalla W, Gómez-Raja J, Epstein M, Sanderman R, Schulz SVW, Jerg A, Al-Horani R, Mansi T, Jmail M, Barbosa F, Ferreira-Santos F, Šimunič B, Pišot R, Gaggioli A, Bailey SJ, Steinacker JM, Driss T, Hoekelmann A (2020) Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behaviour and physical activity: results of the ECLB-COVID19 international online survey. Nutrients 12:1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12061583

Zachary Z (2021) COVID-19 Self-quarantine and Weight Gain Risk Factors in Adults. Curr Obes Rep 10:423–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-021-00449-7/Published

Cheikh Ismail L, Osaili TM, Mohamad MN, Al Marzouqi A, Jarrar AH, Zampelas A, Habib-Mourad C, Jamous DOA, Ali HI, Al Sabbah H, Hasan H, Almarzooqi LMR, Stojanovska L, Hashim M, Shaker Obaid RR, Elfeky S, Saleh ST, Shawar ZAM, Al Dhaheri AS (2021) Assessment of eating habits and lifestyle during the coronavirus 2019 pandemic in the Middle East and North Africa region: a cross-sectional study. Br J Nutr 126:757–766. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114520004547

Bakaloudi DR, Jeyakumar DT, Jayawardena R, Chourdakis M (2021) The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on snacking habits, fast-food and alcohol consumption: a systematic review of the evidence. Clin Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2021.04.020

McBride O, Bunting E, Harkin O, Butter S, Shevlin M, Murphy J, Mason L, Hartman TK, McKay R, Hyland P, Levita L, Bennett KM, Stocks TVA, Gibson-Miller J, Martinez AP, Vallieres F, Bentall RP (2022) Testing both affordability-availability and psychological-coping mechanisms underlying changes in alcohol use during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 17:e0265145. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265145

Ezhilarasan D (2021) Hepatotoxic potentials of methotrexate: understanding the possible toxicological molecular mechanisms. Toxicology 458:152840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2021.152840

Ladani AP, Loganathan M, Danve A (2020) Managing rheumatic diseases during COVID-19. Clin Rheumatol 39:3245–3254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05387-8/Published

Azizov V, Zaiss MM (2021) Alcohol consumption in rheumatoid arthritis: a path through the immune system. Nutrients 13:1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13041324

Turk JN, Zahavi ER, Gorman AE, Murray K, Turk MA, Veale DJ (2021) Exploring the effect of alcohol on disease activity and outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis through systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 11:10474. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89618-1

Minzer S, Losno RA, Casas R (2020) The effect of alcohol on cardiovascular risk factors: is there new information? Nutrients 12:1–22. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12040912

Wieczorek M, Gwinnutt JM, Ransay-Colle M, Balanescu A, Bischoff-Ferrari H, Boonen A, Cavalli G, de Souza S, de Thurah A, Dorner TE, Moe RH, Putrik P, Rodríguez-Carrio J, Silva-Fernández L, Stamm TA, Walker-Bone K, Welling J, Zlatkovic-Svenda M, Verstappen SM, Guillemin F (2022) Smoking, alcohol consumption and disease-specific outcomes in rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs): systematic reviews informing the 2021 EULAR recommendations for lifestyle improvements in people with RMDs. RMD Open 8https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2021-002170

Abdelhamid L, Luo XM (2022) Diet and Hygiene in Modulating Autoimmunity During the Pandemic Era. Front Immunol 12:749774. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.749774

Boaz M, Navarro DA, Raz O, Kaufman-Shriqui V (2021) Dietary changes and anxiety during the coronavirus pandemic: differences between the sexes. Nutrients 13:4193. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124193

Alfawaz H, Amer OE, Aljumah AA, Aldisi DA, Enani MA, Aljohani NJ, Alotaibi NH, Alshingetti N, Alomar SY, Khattak MNK, Sabico S, Al-Daghri NM (2021) Effects of home quarantine during COVID-19 lockdown on physical activity and dietary habits of adults in Saudi Arabia. Sci Rep 11:5904. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-85330-2

Clemente-Suárez VJ, Ramos-Campo DJ, Mielgo-Ayuso J, Dalamitros AA, Nikolaidis PA, Hormeño-Holgado A, Tornero-Aguilera JF (2021) Nutrition in the actual covid-19 pandemic. A narrative review. Nutrients 13:1924. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13061924

Skotnicka M, Karwowska K, Kłobukowski F, Wasilewska E, Małgorzewicz S (2021) Dietary habits before and during the covid-19 epidemic in selected European countries. Nutrients 13:1690. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13051690

Zehirlioglu L, Mert H, Sezgin D, Özpelit E (2020) Cardiovascular Risk, Risk Knowledge, and Related Factors in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Clin Nurs Res 29:322–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054773819844070

Dougados M, Soubrier M, Antunez A, Balint P, Balsa A, Buch MH, Casado G, Detert J, El-Zorkany B, Emery P, Hajjaj-Hassouni N, Harigai M, Luo SF, Kurucz R, Maciel G, Mola EM, Montecucco CM, McInnes I, Radner H, Smolen JS, Song YW, Vonkeman HE, Winthrop K, Kay J (2014) Prevalence of comorbidities in rheumatoid arthritis and evaluation of their monitoring: results of an international, cross-sectional study (COMORA). Ann Rheum Dis 73:62–68. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204223

Zhu Y, Zhong J, Dong L (2021) Epidemiology and clinical management of rheumatic autoimmune diseases in the COVID-19 pandemic: a review. Front Med (Lausanne) 8:725226. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.725226

de Resende Guimarães MFB, Rodrigues CEM, Gomes KWP, MacHado CJ, Brenol CV, Krampe SF, de Andrade NPB, Kakehasi AM (2019) High prevalence of obesity in rheumatoid arthritis patients: association with disease activity, hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes, a multi-center study. Adv Rheumatol 59:44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42358-019-0089-1

Azarfar A, Ahmed A, Bég S (2021) Prevalence of Anxiety, Depression, Sleep Disturbance, Fibromyalgia, Obesity, and Gastroesophageal Disease in Patients with Rheumatic Diseases. Curr Rheumatol Rev 17:252–257. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573397116666201211124815

Liu Y, Hazlewood GS, Kaplan GG, Eksteen B, Barnabe C (2017) Impact of obesity on remission and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 69:157–165. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22932

Moroni L, Farina N, Dagna L (2020) Obesity and its role in the management of rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 39:1039–1047. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-04963-2

Zhu Q, Li M, Ji Y, Shi Y, Zhou J, Li Q, Qin R, Zhuang X, Mcaleer M, Chang C-L, Slottje DJ, Amaral TP (2021) Outbreak Confinement in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18:1813. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph

Sánchez E, Lecube A, Bellido D, Monereo S, Malagón MM, Tinahones FJ (2021) Leading factors for weight gain during covid-19 lockdown in a Spanish population: a cross-sectional study. Nutrients 13:1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030894

Kriaucioniene V, Bagdonaviciene L, Rodríguez-Pérez C, Petkeviciene J (2020) Associations between changes in health behaviours and body weight during the covid-19 quarantine in Lithuania: the Lithuanian Covidiet study. Nutrients 12:1–9. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12103119

Poskute AS, Nzesi A, Geliebter A (2021) Changes in food intake during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City. Appetite. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105191

Li X, Li J, Qing P, Hu W (2021) COVID-19 and the change in lifestyle: bodyweight, time allocation, and food choices. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910552

Fouad AM, Elotla SF, Elkaraly NE, Mohamed AE (2022) Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases: disruptions in care and self-reported outcomes. J Patient Exp 9:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/23743735221102678

Sharifi Y, Payab M, Mohammadi-Vajari E, Aghili SMM, Sharifi F, Mehrdad N, Kashani E, Shadman Z, Larijani B, Ebrahimpur M (2021) Association between cardiometabolic risk factors and COVID-19 susceptibility, severity, and mortality: a review. J Diabetes Metab Disord 20:1743–1765. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-021-00822-2

Santos CS, Morales CM, DíezÁlvarez E, Castro CA, Robles AL, Perez Sandoval T (2020) Determinants of COVID-19 disease severity in patients with underlying rheumatic disease. Clin Rheumatol 39:2789–2796. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05301-2/Published

Fucile I, Manzi MV, Mancusi C (2021) Blood Pressure and Lipid Profile in Hypertensive Patients Post the First COVID-19 Lockdown: “Brief Letter for Publication.” High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev 28:493–494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40292-021-00470-w

Pengo MF, Albini F, Guglielmi G, Mollica C, Soranna D, Zambra G, Zambon A, Bilo G, Parati G (2022) Home blood pressure during COVID-19-related lockdown in patients with hypertension. Eur J Prev Cardiol 29:E94–E96. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjpc/zwab010

Girerd N, Meune C, Duarte K, Vercamer V, Lopez-Sublet M, Mourad J-J (2021) Evidence of a blood pressure reduction during the COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdown period: insights from e-Health data. Telemed J e-Health. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2021.0006ï

Manent JIR, Jané BA, Cortés PS, Busquets-Cortés C, Bote SA, Comas LM, González ÁAL (2022) Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on anthropometric variables, blood pressure, and glucose and lipid profile in healthy adults: a before and after pandemic lockdown longitudinal study. Nutrients. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14061237

Gianfrancesco M, Hyrich KL, Al-Adely S, Al-Adely S, Carmona L, Danila MI, Gossec L, Gossec L, Izadi Z, Jacobsohn L, Katz P, Lawson-Tovey S, Lawson-Tovey S, Mateus EF, Rush S, Schmajuk G, Simard J, Strangfeld A, Trupin L, Wysham KD, Bhana S, Costello W, Grainger R, Hausmann JS, Liew JW, Sirotich E, Sirotich E, Sufka P, Wallace ZS, Wallace ZS, Yazdany J, MacHado PM, MacHado PM, MacHado PM, Robinson PC, Robinson PC (2020) Characteristics associated with hospitalisation for COVID-19 in people with rheumatic disease: data from the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance physician-reported registry. Ann Rheum Dis 79:859–866. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217871

Pablos JL, Galindo M, Carmona L, Lledó A, Retuerto M, Blanco R, Gonzalez-Gay MA, Martinez-Lopez D, Castrejón I, Alvaro-Gracia JM, Fernández Fernández D, Mera-Varela A, Manrique-Arija S, Mena Vázquez N, Fernandez-Nebro A (2020) Clinical outcomes of hospitalised patients with COVID-19 and chronic inflammatory and autoimmune rheumatic diseases: a multicentric matched cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 79:1544–1549. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218296

Freites Nuñez DD, Leon L, Mucientes A, Rodriguez-Rodriguez L, Font Urgelles J, Madrid García A, Colomer JI, Jover JA, Fernandez-Gutierrez B, Abasolo L (2020) Risk factors for hospital admissions related to COVID-19 in patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis 79:1393–1399. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217984

Galarza-Delgado DA, Azpiri-Lopez JR, Colunga-Pedraza IJ, Cárdenas-de la Garza JA, Vera-Pineda R, Wah-Suárez M, Arvizu-Rivera RI, Martínez-Moreno A, Ramos-Cázares RE, Torres-Quintanilla FJ, Valdovinos-Bañuelos A, Esquivel-Valerio JA, Garza-Elizondo MA (2017) Prevalence of comorbidities in Mexican mestizo patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int 37:1507–1511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-017-3769-3

Pham A, Brook J, Elashoff DA, Ranganath VK (2022) Impact of perceived stress during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on rheumatoid arthritis patients’ disease activity: an online survey. Clin Rheumatol 28:333–337. https://doi.org/10.1097/RHU.0000000000001861

Florence A, Nassim AA, Jean-David A, Yannick A, Blanca AB, Zahir A, Emma A, Jean-Benoît A, Laurent A, Denis A, Herliette AH, Lucie A, Christine AP, Victor A, Maxime BB, Hélène BD, Brigitte BM, Nathalie B, Jean-Charles B, Stéphane B, Frédéric B, Béatrice B, Thomas B, Audre B, André B, Vincent B, Guillaume B, Sophie B, Véronique B, Rakiba B, Ruben B, Alexandre B, Mohammed B, Mathilde B, Ygal B, Ahmed B, Pascal B, Brigitte BM, Emilie B, Ewa B, Aurélia BV, Gilles B, Gilles B, Olivier B, Christine B, Raphaël B, Laurence B, Françoise B, Kévin B, Bastien B, Karima B, Eric B, Regine B, Pierre B, Patrice C, Maurizio C, Aurélia C, Brice C, Pascal C, Hervé C, Annalisa C, Benjamin C, Benoît C, Romuald C, Agnès C, Pierre C, Isabelle CL, Caroline C, Emmanuel C, Bernard C, Pascal C, Pascale C, Xavier C, Maxime C, Emilie C, Delphine CML, Pascal C, Gaëlle C, Cyril CO, Fleur C, Gregory C, Marie-Eve CC, Nived C, Antoine C, Chloé C, Bernard C, Céline C, Elodie C, Clémence C, Nathalie CC, Marie C, Natacha C, Fabienne CL, Cécile C, Fabrice C, Richard D, Laurence DM, Sarahe D, Michel D, Elise D, Chantal D, Marie D, Jacques D, Marie D, Frédérick D, Valérie DP, Mathilde D, Robin D, Philippe D, Yannick D, Elisabeth D, Djamal-Dine D, Fanny D, Béatrice D, Elodie D, Catherine D, Angélique D, Carine DL, Alain D, Cécile D, Anne-Elisabeth D, Géraldine D, Pierre-Marie D, Mikaël E, Esther E, Andra ED, Soumaya EM, Romain E, Philippe E, Sylvie F, Marion F, Bruno F, Jacques F, Renaud F, Fanny F, Nicole FM, Elodie F, Amandine F, Françoise F, René-Marc F, Nans F, Violaine F, Elisabeth F, Jennifer F, Anne-Claire F, Anne FA, Catherine FM, Hélène FP, Léa F, Pierre F, Antoine F, Jean F, Piera F, Francis G, Laurence GL, Mélanie GP, Joris G, Frédérique G, Nicole G, Thomas G, Jean-François G, Romain G, Véronique GL, Maud GP, Dana G, Sophie GL, Nathalie G, Elisabeth G, Christelle G, Eric G, Ghislaine G, Jérôme G, Mélanie G, Pauline G, Jeanine-Sophie GLQ, Aude GM, Baptiste G, Camille G, Bertrand G, Bruno G, Camille GG, Tiphaine G, Philippe G, Olivier G, Sophie GA, Franck G, Bruno G, Anne G, Gilles G, Monica G, Constance G, Séverine G, Xavier G, Philippe G, Aline G, Marie-Hélène G, Eric H, Cécile HB, Marie-Noelle H, Jean-Pierre H, Pascal H, Basile H, Julien H, Véronique H, Marion H, Muriel H, Miguel H, Ambre HR, Christophe H, Serge H, Clara J, Jean-Michel J, Bénédicte J, Catherine J, Sylvie J, Mathieu J, Pierre-Antoine J, Laurent J, Denis J, Anna K, Abdelkrim K, Ludovic K, Françoise K, Farid K, Jérémy K, Isabelle KP, Abdeldajallil K, Sylvain LBA, Pierre L, Sophie L, Vincent L, Sylvain L, Aurélia L, Jean-Paul L, Augustin L, Christian L, Sophie LGG, Guillaume LG, Agnès L, Emmanuel L, Nathalie L, Erick L, Charlotte L, Olivier L, Christophe L, Rémi L, Tifenn L, Frédéric U, Anne L, Virginie L, Aurélie M, Matthieu M, Hélène M, Thibault M, Sandrine MG, Quentin M, Sylvie ML, Nathalie M, Thierry M, Alexandre M, Xavier M, Hubert M, Alexis M, François M, Frédéric M, Betty MG, Arnaud M, Hassan M, Nadia MC, Ulrich M, Arsène M, Isabelle M, Laurent M, Martin M, Mathilde M, Anne-Marie ML, Anna M, Marie M, Olivier M, Gautier M, Hugo M, Jacques M, Franck M, Laurence M, Guillaume M, Bertrand M, Minh N, Sabine NV, Hubert N, Gaétane N, Henri-Olivier O, Isabelle PV, Caroline P, Antoine P, Tristan P, Yasmina PM, Laetitia P, Stephan P, Laurent P, Yves-Marie P, Edouard P, Micheline P, Thao P, Guillaume D, Maud P, Gabrielle AP, Elsa P, Agnès P, Jacques P, Antoine P, Samira P, Grégory P, Déborah PZ, Pierre QDM, Marion Q, Philippe R, Myriam R, Jessica R, Sabine R, Gaëlle RC, Christophe R, Etienne R, Sébastien R, Sophie R, Julien R, Isabelle R, Mélanie R, Michel R, Mélanie R, Linda R, Olivier R, Sid-Ahmed R, Mathilde R, Mickaël R, Clémentine R, Christian R, Fabienne R, Marielle R, Nicolas R, Diane R, Sylvie R, Isabelle S, Fatiha S, Laurent S, Carine S, Jean-Hugues S, Jean S, Julie S, Jérémie S, Eric S, Thomas S, Patricia S, Raphaële S, Amélie S, Pascal S, Aurélie S, Perrine S, Vincent S, Christelle S, Elisabeth SR, Odile SD, Laetitia S, Sarah S, Victor S, Paulina S, Séverine TC, Justine S, Nora T, Benoît T, Thierry T, Nathalie T, Auk T, Eric T, Ludovic T, Sophie T, Sébastien T, Truchetet ME, Eric V, Laurent V, Guillaume V, Jean-François V, Judith V, Claire V, Mathias V, Camille V, Alexandre V, Ursula W, Daniel W, Claude W, Alexandra W, Michel W, Juliette W, Bernadette XC, Didier A (2021) Severity of COVID-19 and survival in patients with rheumatic and inflammatory diseases: data from the French RMD COVID-19 cohort of 694 patients. Ann Rheum Dis 80:527–538. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218310

Jamthikar AD, Gupta D, Puvvula A, Johri AM, Khanna NN, Saba L, Mavrogeni S, Laird JR, Pareek G, Miner M, Sfikakis PP, Protogerou A, Kitas GD, Kolluri R, Sharma AM, Viswanathan V, Rathore VS, Suri JS (2020) Cardiovascular risk assessment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis using carotid ultrasound B-mode imaging. Rheumatol Int 40:1921–1939. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04691-5

Wah-Suarez MI, Galarza-Delgado DA, Azpiri-Lopez JR, Colunga-Pedraza IJ, Abundis-Marquez EE, Davila-Jimenez JA, Guillen-Gutierrez CY, Elizondo-Riojas G (2019) Carotid ultrasound findings in rheumatoid arthritis and control subjects: a case-control study. Int J Rheum Dis 22:25–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185X.13377

Jontez NB, Novak K, Kenig S, Petelin A, Pražnikar ZJ, Mohorko N (2021) The impact of COVID-19-related lockdown on diet and serum markers in healthy adults. Nutrients. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13041082

Perrone MA, Feola A, Pieri M, Donatucci B, Salimei C, Lombardo M, Perrone A, Parisi A (2021) The effects of reduced physical activity on the lipid profile in patients with high cardiovascular risk during covid-19 lockdown. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168858

Tüfekçi D, Coskun H, Ünal E, Emür Y, Demir A, Bilginer MC, Nuhoğlu I, Üçüncü O, Koçak M (2021) Evaluation of the effect of the COVID -19 ‘Lockdown Process’ on the clinical and metabolic parameters of obese patients: a single center cross-sectional study. Turk J Diab Obes 5:186–192. https://doi.org/10.25048/tudod.946756

Liu Y, Pan Y, Yin Y, Chen W, Li X (2021) Association of dyslipidemia with the severity and mortality of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a meta-analysis. Virol J 18:157. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-021-01604-1

Atmosudigdo IS, Lim MA, Radi B, Henrina J, Yonas E, Vania R, Pranata R (2021) Dyslipidemia increases the risk of severe COVID-19: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Clin Med Insights Endocrinol Diabetes. https://doi.org/10.1177/1179551421990675

Tektonidou MG, Kravvariti E, Konstantonis G, Tentolouris N, Sfikakis PP, Protogerou A (2017) Subclinical atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus: comparable risk with diabetes mellitus and rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun Rev 16:308–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2017.01.009

González-Rangel J, Pérez-Muñoz B, Casillas-Santos D, Barrera-Vargas A, Vázquez-Cardenas P, Escamilla-Santiago R, Merayo-Chalico J (2021) Mental health in patients with rheumatic diseases related to COVID-19 pandemic: experience in a tertiary care center in Latin America. Lupus 30:1879–1887. https://doi.org/10.1177/09612033211038052

Wańkowicz P, Szylińska A, Rotter I (2020) Evaluation of mental health factors among people with systemic lupus erythematosus during the sars-cov-2 pandemic. J Clin Med 9:1–8. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9092872

Ahmed S, Gasparyan AY, Zimba O (2021) Comorbidities in rheumatic diseases need special consideration during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rheumatol Int 41:243–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04764-5

Saeed A, Kampangkaew J, Nambi V (2017) Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Women. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J 13:185–192. https://doi.org/10.14797/mdcj-13-4-18

Minhas S, Patel JR, Malik M, Hana D, Hassan F, Khouzam RN (2022) Mind-body connection: cardiovascular sequelae of psychiatric illness. Curr Probl Cardiol 47(10):100959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2021.100959

Maki K, Koji H (2021) Coronavirus disease 2019: psychological stress and cardiovascular diseases. European Cardiology Review 16:34–37. https://doi.org/10.1192/bji.2019.5

Ma L (2020) Depression, anxiety, and apathy in mild cognitive impairment: current perspectives. Front Aging Neurosci 12:9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2020.00009

Soysal P, Smith L, Trott M, Alexopoulos P, Barbagallo M, Tan SG, Koyanagi A, Shenkin S, Veronese N (2022) The Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia or mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychogeriatrics 22(3):402–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.1281

Schwartz N, Stock AD, Putterman C (2019) Neuropsychiatric lupus: new mechanistic insights and future treatment directions. Nat Rev Rheumatol 15:137–152. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41584-018-0156-

Chaurasia N, Singh A, Singh I, Singh T, Tiwari T (2020) Cognitive dysfunction in patients of rheumatoid arthritis. J Family Med Prim Care 9:2219. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_307_20

Bartolini M, Candela M, Brugni M, Catena L, Mari F, Pomponio G, Provinciali L, Danieli G (2002) Are behaviour and motor performances of rheumatoid arthritis patients influenced by subclinical cognitive impairments? A clinical and neuroimaging study. Clin Exp Rheumatol 20:491–497

Lee YX, Kwan YH, Lim KK, Tan CS, Lui NL, Phang JK, Chew EH, Ostbye T, Thumboo J, Fong W (2019) A systematic review of the association of obesity with the outcomes of inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Singapore Med J 60:270–280. https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2019057

Vallerand IA, Patten SB, Barnabe C (2019) Depression and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 31:279–284. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOR.0000000000000597

Salliot C, Nguyen Y, Boutron-Ruault MC, Seror R (2020) Environment and lifestyle: their influence on the risk of RA. J Clin Med 9:1–31. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9103109

Shoenfeld Y, Gerli R, Doria A, Matsuura E, Cerinic MM, Ronda N, Jara LJ, Abu-Shakra M, Meroni PL, Sherer Y (2005) Accelerated atherosclerosis in autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Circulation 112:3337–3347. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.507996

Strangfeld A, Schäfer M, Gianfrancesco MA, Lawson-Tovey S, Liew JW, Ljung L, Mateus EF, Richez C, Santos MJ, Schmajuk G, Scirè CA, Sirotich E, Sparks JA, Sufka P, Thomas T, Trupin L, Wallace ZS, Al-Adely S, Bachiller-Corral J, Bhana S, Cacoub P, Carmona L, Costello R, Costello W, Gossec L, Grainger R, Hachulla E, Hasseli R, Hausmann JS, Hyrich KL, Izadi Z, Jacobsohn L, Katz P, Kearsley-Fleet L, Robinson PC, Yazdany J, Machado PM (2021) Factors associated with COVID-19-related death in people with rheumatic diseases: results from the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance physician-reported registry. Ann Rheum Dis 80:930–942. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219498

Gwinnutt JM, Wieczorek M, Balanescu A, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Boonen A, Cavalli G, de Souza S, de Thurah A, Dorner TE, Moe RH, Putrik P, Rodríguez-Carrio J, Silva-Fernández L, Stamm T, Walker-Bone K, Welling J, Zlatković-Švenda MI, Guillemin F, Verstappen SMM (2022) 2021 EULAR recommendations regarding lifestyle behaviours and work participation to prevent progression of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. Ann Rheum Dis annrheumdis-2021–222020. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-222020

Schuch FB, Stubbs B (2019) The role of exercise in preventing and treating depression. Curr Sports Med Rep 18(8):299–304. https://doi.org/10.1249/JSR.0000000000000620

Acknowledgements

We thank Sergio Lozano-Rodríguez, M.D., MWC, for his help in editing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. The idea for the article was performed by Jesus Alberto Cardenas-de la Garza. The literature search was performed by Valeria Gonzalez-Gonzalez, Victor M. Beltran-Aguilar, Angel G. Arias-Peralta, and Natalia De Avila-Gonzalez. The work was critically revised by Dionicio A. Galarza-Delgado, Iris J. Colunga-Pedraza, Jose R. Azpiri-Lopez, Jesus Alberto Cardenas-de la Garza, and Natalia Guajardo-Jauregui. The first draft was written by Valeria Gonzalez-Gonzalez, Victor M. Beltran-Aguilar, Angel G. Arias-Peralta, and Natalia De Avila-Gonzalez and all commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The manuscript does not contain clinical studies or patient data.

Disclosures

None.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Part of the Topical Collection entitled ‘Cardiovascular Issues in Rheumatic Diseases’

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Galarza-Delgado, D.A., Azpiri-Lopez, J.R., Colunga-Pedraza, I.J. et al. Cardiovascular health worsening in patients with autoimmune rheumatological diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Rheumatol 42, 2677–2690 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-022-06486-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-022-06486-4