Abstract

Depression is a common co-morbidity among rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients, which may translate into difficulty performing activities of daily living. COVID-19 is an unprecedented disaster that has disrupted lives worldwide and led to a rise in the incidence of mental health disorders. Given the widespread economic devastation due to COVID-19, many RA patients, already susceptible to mental illness, maybe at an increased risk of inaccessibility to medical care, accentuated stress, and consequent worsening of existent mental health disorders, or the onset of new mental health disorders such as anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, or depression. The objective of this review is to assess if there is an increased risk of mental health disorders in patients with RA during the COVID-19 pandemic. Telemedicine has bridged the transition to remote chronic care in the pandemic period, though certain accessibility and technological challenges are to be addressed. Decreased access to care amid lockdowns and a proposed triggering of disease activity in patients with autoimmune disorders may potentially herald a massive spike in incidence or flares of patients diagnosed with RA in the coming months. Such a deluge of cases may be potentially devastating to an overburdened healthcare system. Rheumatologists may need to prepare for this eventuality and explore techniques to provide adequate care during these challenging times. The authors found that there is a significant association between the adverse impact on the mental health of RA patients and the COVID-19 pandemic. However, more research is needed to highlight individual risk factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic rheumatic diseases (RDs) are associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Of these, adverse mental health is a major contributor to poor quality of life. Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) affects 0.2–1.2% of the general population and would amount to a large number of diseased individuals in a large country like India with a population base of 1.3 billion people [1]. Depression is highly prevalent among patients with RA, amounting to 13–42% of individuals in various studies [2,3,4,5].

It is anticipated that in the post-COVID-19 era, due to a backlog of patients, there may be a rise in outpatient waiting lists. Moreover, the proposed activation of the interferon axis in clearing the virus may put patients with RDs are an additional risk of flares of disease. It remains to be explored if this translates into a higher incidence of RA in the genetically predisposed. A rise in cases can add to the challenge of a low number of rheumatologists in India [6], already serving a staggering patient load. Such an increase in cases combined with a lack of specialists may lead to delayed diagnoses, increased inaccessibility to care, and further stressing the primary care system. India’s rheumatology and primary care workforces also face a significant risk of physician burnout, professional dissatisfaction, and possibly a greater number of lawsuits due to worse patient outcomes. A rise in incident mental health disorders in this group is anticipated, further increasing the burden on psychiatrists and psychologists.

Rheumatologists and psychiatrists need to be aware of this possibility and a better understanding of the incoming tide may help them handle the surge better. The authors review the impact of COVID-19 on patients with RA, their mental health and explore potential solutions to stem the coming tide, such as telemedicine, community-based medication, and therapy programs, and mental health interventions.

Materials and methods

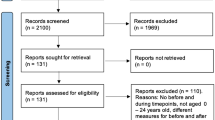

For this narrative review article, a literature review was conducted on PUBMED and SCOPUS databases by AB and MKC to identify articles in English on the subject. The search terms used were “COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV2 OR SARS-COV-2 OR novel coronavirus OR nCOV OR pandemic”, “Mental health disorders OR Depression OR anxiety”, “Rheumatoid arthritis OR RA OR Arthritis OR Rheumatoid”, “Telemedicine OR Telehealth OR Teleconsultation”, “Health service accessibility”.

The search with a combination of the above phrases returned 1126 results. These were independently reviewed and the relevant information was extracted for this narrative review, which was a total of 60 articles.

The review paper has only included data from 2013 till the start of 2021 and does not include animal studies. Thus, it could miss some important studies beyond this study period. The pandemic is an evolving situation, and some points made in this paper could be made moot by a return to normal life.

The interplay of Covid-19, RA care, and mental health

COVID-19 is the world’s worst health crisis in 100 years. A well-documented effect of this tragedy has been the increased incidence rate of depression globally. In a survey performed by the University of Chicago, approximately two-thirds of the US population stated that they were suffering from anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem due to the COVID-19 pandemic [7]. A meta-analysis of 72 studies which included 13,189 patients with RA showed that the prevalence of depression was 16.8% ((95% CI 10–24%). The same analysis found that depression in patients with RA led to significantly poorer outcomes [8]. Another study of 172 patients showed that illness severity was remarkably related to depression, which was also impacted minority communities more severely [9].

A British study found that adults had increased rates of suicidal thoughts due to the lockdown [10]. Recently Cleaton et al. [11] examined the impact of stringent Covid-19 era social distancing on the Health-Related Quality of Life at a UK rheumatology center. The study revealed a considerable decrease in the mental component score in the coronavirus infected patients’ group than when compared to non-infected patients. In patients without COVID-19, the ‘shielding’ group exhibited a decline in mental as well as physical component scores, suggesting a statistically significant psychological impact of social isolation, when the patients adhered to public advisory during the lockdown period by not leaving the house and having minimal social interactions.

During the lockdown, patients with RA have experienced increased pain and functional impairment, both of which are associated with increased incidence rates of depression, anxiety, insomnia, decreased self-worth, and other mental health disorders. The World Health Organization (2020) reports that the elderly are more likely to be concerned, nervous, and annoyed during the quarantine period [2].

Regrettably, this population also has the highest incidence of RA, placing the elderly at the cross-section of worsening mental health, morbidity due to RA, lack of access to care due to the lockdown, and an overburdened health system coming apart at the seams [12]. This is being seen around the world, with decreasing rheumatology visits, and patient compliance [13, 14].

RA is associated with a higher prevalence of functional impairment which is seen in at least 15.8% of patients with RA [15]. Functional impairment due to RA leads to loss of productivity and absenteeism from work, increased health care expenses, and decreased quality of life [15]. Functional impairment is a strong predictor of depression in patients with RA [16] and is also associated with an increased risk of suicide [16].

Due to the massive financial upheaval caused by the pandemic, individuals who have lost their jobs are at a higher risk of depression, anxiety, and other mental health disorders [17]. The RA patient population is already at a higher risk for leaving the workforce due to RA-associated disability [18]. Since employment is correlated with greater self-esteem and access to care in patients with RA, losing employment due to COVID-19 may be detrimental to the mental health of patients with RA. A dangerous combination of these factors might precipitate a joblessness crisis among the RA patient population, with a superimposed deterioration of mental health. There is an urgent need to explore and understand the impact of COVID-19 associated unemployment on the mental health of patients with RA in the post-pandemic period.

Beyond the physical and mental effects of the lockdowns, patients may opt to wait for essential procedures due to the fear of contracting COVID-19, decreased hospital capacity, and many centers opting to suspend non-emergent procedures [19]. Delays in surgeries due to the COVID-19 pandemic have led to significant anxiety amongst those opting for elective surgery [20], with most hoping to schedule their surgery as soon as possible. This signals a surge in elective surgery cases after the COVID-19 pandemic abates, again increasing the risk for physician burnout, poorer outcomes, and increased lawsuits among surgeons. Unfortunately, there has been rather limited research available for patients with RA delaying procedures and treatment, and this remains an area that needs investigation to grasp the full scope of the problem.

The vicious cycle

One key factor determining mental health is the bidirectional relationship between physical and mental well-being. An abundance of evidence shows that deteriorating mental health worsens RA symptoms, which in turn adversely affects the mental health of the patient. A systemic review found that depression in the RA patient population may intensify pain and illness activity, decrease the effectiveness of treatment, and adversely affect patient outcomes [21]. RA affects the quality of life [22], increases pain [23], exhaustion [24], health care usage [25], and increased the possibility of untimely death.

Mental health disorders also directly contribute to RA symptom-related outcomes including pain [26], which is the most common presentation of RA that persists even after inflammation is controlled [27, 28]. Dealing with the pain that is associated with RA flares presents a daunting task for any patient, with duration and severity of depression being a risk factor for pain intensity [29]. Experiencing mental distress may increase patient-reported symptoms of pain and tenderness [30]. Mental distress increases non-adherence to medications [31] and smoking [32].

Tying these individual metrics of patient wellness together, there emerges a clear cyclical relationship between RA disease activity and mental health. Thus, there is a vicious cycle of RA flares and symptoms worsening mental health, which in turn worsens the RA via increased symptoms and non-adherence. This in turn adversely affects mental health and so on, into a downward spiral. Superimposition of unemployment and isolation onto this already vulnerable patient population may lead to a drastic increase in mental health disorders, poorer outcomes, and decreased quality of life (Qol) of the patient (Fig. 1).

The vicious cycle of mental health and COVID-19 induced life alterations. The implications of COVID-19 on the mental health of patients with RA and the resultant increase incidence of RA flares. The overall effect of this downward spiral is a decrease in QoL of the patients and worse patient outcomes.

Social support and coping mechanisms

Decreased social support reduces emotional adaptation to the disease [33], increases physical disability and distress [34], and increases the prevalence of depression [35]. Elevated levels of stress and poor illness perception harm emotional and social adjustment to the disease [36] as well as increase the incidence of depression [33]. Patients with RA who have strong social support structures have less severe symptoms of psychological disorders than those who do not [37,38,39]. Hence, strong family support and coping strategies can have an overall positive effect in the short and long-term management of patients with RA. The most important aspect of this research is that it provides a ripe target for intervention, via existing familial and social structures, without the need for massive financial investment.

Use of telemedicine during COVID-19: current status and challenges:

Most consultations during the lockdown period were online, via telemedicine portals. While studies have reported that telemedicine may be equally effective in-person consultations [6]. While telemedicine remains a cost-effective option for delivering health care to patients with RA, being logistically the easiest to implement in urban areas and affluent communities [40], there remain significant barriers to access to telemedicine, especially in rural areas. The lack of availability of mobile devices is a significant challenge to accessibility in developing countries. Equitable access to care remains something that is only talked about in academic and policy circles, with no real progress on the ground.

The elderly, which are the age group most affected by RA, may not be technologically literate enough to access telemedicine [41]. This may result in a lack of access or dependence upon younger members of the household, who may not be always available or willing to dedicate their time and devices.

Telemedicine might also promote the feeling of isolation, as yet another in-person human interaction is moved online contributing to further deterioration of mental health. Physical examinations are limited, depriving clinicians of an essential tool for diagnosis [41]. Moreover, new patients who might be suspected of having rheumatoid arthritis are difficult to diagnose via telemedicine in the absence of overt disease. This may result in delayed intervention and eventually worse outcomes. Delayed infusions due to the lockdown and job loss have had a negative impact on patients with RDs (rheumatoid disorders) during the pandemic [42, 43]. Certain patient subgroups among those with RDs can be more challenging to manage with telemedicine than others [44].

Online counselling services and mental health interventions have flourished during this period, and while protocols for systematic reviews have been published [45], there seems to be a lack of consensus on the effectiveness of such services [46]. It would be optimal to stratify patients with RA according to RMDs (rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases) as per the presence and number of comorbidities, to help determine risk for severe COVID-19. Teleconsultation is uniquely suited to serve this purpose [47].

Potential solutions

In light of the evidence reviewed above; a mental health-focused approach is necessary for clinical practice in rheumatology going forward. Given the nature of the lockdowns imposed due to COVID-19, with non-emergent medical services being severely curtailed or stopped completely, patients with RA may be increasingly isolated, unable to reach out to their physician or support system in a time of need. Moreover, mitigation of the anticipated rise in cases is paramount. The authors recommend the following steps, some, or all of which can be explored by rheumatologists.

A community-based intervention program focused on patients with RA is an option that local physician groups can implement. The patients can be reached either via telemedicine for counselling or via visiting groups that focus on physical as well as mental therapy. Establishment of programs in conjunction with local pharmacies aimed at ensuring the availability of RA drugs to patients at all times. Given the hydroxychloroquine shortage and general lack of mobility due to the lockdowns, this can be an essential step in ensuring patient compliance to therapy [26]. If a hybrid model between telemedicine, community-based groups for infusions and medications, and counselling can be implemented, it would serve as a balanced and reasonable vehicle for delivering healthcare to patients with RA, while also decreasing the burden on specialists.

Management of depression in patients with RA may not only improve mental health but also decrease pain, enhances the functional status and quality of life [48], and enhance response to treatment [49]. Passive coping and low self-confidence are significant predictors of depression in patients with RA [9]. Mandating a psychiatry consult at the time of diagnosis, regular screenings, along with training rheumatologists and family members to identify common signs of depression can help get patients the help they need.

Telemedicine has seen a boom in use during the pandemic. Due to the nature of RA and the follow-ups required, telemedicine consultations became the consultation of choice [44]. Given that most patients were satisfied with the telemedicine consultations and intended to continue them even after the pandemic, telemedicine is here to stay [50]. There are accessibility issues with telemedicine in rural areas. This can be countered by the government. or charitable programs aimed at boosting connectivity. This has the additional benefit of empowering citizens digitally and financially. In addition to consultations by experts via telemedicine, a home visit by community health workers to improve compliance, deliver medication, provide services such as physiotherapy can be a bedrock of such a community program. An exercise regimen, with compliance being monitored via telemedicine, can be beneficial to patients with RA in both reducing the severity of symptoms and improving their mental health [51, 52].

Although Indians generally tend to be more resilient to adversity and black swan events in general [53], consultants might counsel patients with RA on the need to stock up on essential items such as medication, food, etc.

While pain management remains one of the most challenging aspects of clinical practice, it is essential for improving QoL and the mental health of the patient. The current guidelines on pain management recommend initially asking the patient about their level of pain along with the level of functional impairment associated with the pain [54]. It is essential that the pain management strategy must be tailored to each patient’s situation, triggers, and amplified pain pathways.

Pharmacological intervention remains the core component of pain management in RA, with NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), paracetamol, opioids, and intra articular glucocorticoid injections being the most effective options [54]. The EULAR guidelines also recommend that NSAIDs and their safety needs further evaluation for patients with RA. Just as important to pain management is to avoid medications that do not provide relief to the patients but are widely used as adjuvant pain therapy in patients with RA, such as benzodiazepines. The use of such medications has been shown to not have any positive effect on pain management goals, while significantly increasing the rate of adverse effects [55]. Beer’s criteria [56] should be followed when treating pain in elderly patients.

Capacity building, short training courses for internal medicine doctors in rheumatology, specialized nurses are some of the potential solutions for decreasing the impact of the post-COVID-19 spike in RA cases. Counselling family members to be sensitive to the mental and physical health needs of Patients with RA can provide an extra line of defence against mental health problems. The participation of psychiatrists and psychologists is essential to deal with the surge in mental illnesses due to the adversarial impact of the pandemic (Fig. 2), Table 1.

Conclusion

There is a strong association between depression and suicide ideation in patients with RA with depression, both acting synergistically, to send patient outcomes plummeting. It is evident that arthritis patients in general and patients with RA especially are at a higher risk for mental health disorders, although individual risk factors have not been elicited as of the time of this writing.

Given the accentuated risk of flares in RA and the inability to access care for a prolonged period due to the lockdown, the authors suspect a surge in cases for outpatient departments, procedures, and testing. The rheumatology community needs to prepare itself with novel solutions and increased numbers to handle the rise in cases, without compromising the quality of care. In light of the unique situation that the pandemic has presented, further research is paramount to understanding the quantum of adverse mental impact, determinants, and possible solutions for efficient management. More research needs to be done in certain areas, especially with regards to the financial impact of COVID-19 on Patients with RA, its interplay with mental health, and methods to improving accessibility to telemedicine, in an equitable and just manner. A few solutions which can be explored, based on existing research are increased screening for mental health disorders which is key to improving outcomes and improving the QoL of the RA patient population. Early recognition and intervention in RA cases decrease the prevalence of depression and suicidal risk. This also reduces disease burden; health care costs and improves the quality of life. Early intervention has perhaps the highest value in improving patient outcomes; hence the authors recommend instituting screening protocols for the general public to provide intervention as soon as possible. Another promising approach tailor-made for the pandemic are community-based intervention programs for those who are affected by the pandemic to provide them with access to medication, infusions, consultations, and mental health interventions.

Thus, evidence suggests that patients with arthritis in general and rheumatoid in particular may be at additional risk for adverse mental health during the pandemic. However, evidence on the direct and indirect impact of the situational and the disease-related factors is not known yet. More research in this area will help doctors and policymakers get the information they need to make informed decisions regarding care and policy, respectively. More ambitiously, a special program for patients with RA specialized in employment according to their abilities can be started on a pilot basis, which may become a model for a larger program if the pilot is successful. In view of abbreviated healthcare during the pandemic period and a possibly accentuated risk of flares of arthritis, we may be at the helm of a surge in outpatient appointments and waitlists. Rheumatologists need to be aware of the possibility, and the unique situation calls for structured studies to analyse the quantum of adverse mental impact, determinants, and possible solutions for efficient management.

References

Census of India: Area And Population. https://censusindia.gov.in/census_and_you/area_and_population.aspx. Accessed 8 Jan 2021

Dickens C, McGowan L, Clark-Carter D, Creed F (2002) Depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 64:52–60

Wright GE, Parker JC, Smarr KL et al (1998) Age, depressive symptoms, and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 41:298–305. https://doi.org/10.1002/1529-0131(199802)41:2%3C298::AID-ART14%3E3.0.CO;2-G

Abdel-Nasser AM, Abd El-Azim S, Taal E et al (1998) Depression and depressive symptoms in rheumatoid arthritis patients: an analysis of their occurrence and determinants. Rheumatology 37:391–397. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/37.4.391

Isik A, Koca SS, Ozturk A et al (2007) Anxiety and depression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. ClinRheumatol 26:872–878. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-006-0407-y

Shortage of rheumatologists in India: Experts | Hyderabad News - Times of India. In: Times India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/hyderabad/shortage-of-rheumatologists-in-india-experts/articleshow/78629034.cms. Accessed 11 Jan 2021

Poll: Many Americans feel lonely and anxious during pandemic. (2020) In: AP NEWS. https://apnews.com/article/48019472e2c7fdfa2d1718bd63592f4b. Accessed 4 Jan 2021

Matcham F, Rayner L, Steer S, Hotopf M (2013) The prevalence of depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. RheumatolOxfEngl 52:2136–2148. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ket169

Margaretten M, Yelin E, Imboden J et al (2009) Predictors of depression in a multiethnic cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 61:1586–1591. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.24822

O’Connor RC, Wetherall K, Cleare S et al (2020) Mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: longitudinal analyses of adults in the UK COVID-19 Mental Health & Wellbeing study. Br J Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.212

Cleaton N, Raizada S, Barkham N, et al (2020) COVID-19 prevalence and the impact on quality of life from stringent social distancing in a single large UK rheumatology centre. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. Published Online First: 21 July 2020. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218236. Accessed 13 Jan 2021

Chudasama YV, Gillies CL, Zaccardi F et al (2020) Impact of COVID-19 on routine care for chronic diseases: A global survey of views from healthcare professionals. Diabetes MetabSyndr 14:965–967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.06.042

Ziadé N, el Kibbi L, Hmamouchi I et al (2020) Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients with chronic rheumatic diseases: a study in 15 Arab countries. Int J Rheum Dis 23:1550–1557. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185X.13960

Seyahi E, Poyraz BC, Sut N et al (2020) The psychological state and changes in the routine of the patients with rheumatic diseases during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in Turkey: a web-based cross-sectional survey. RheumatolInt 40:1229–1238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04626-0

Ji J, Zhang L, Zhang Q et al (2017) Functional disability associated with disease and quality-of-life parameters in Chinese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 15:89. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0659-z

Mukherjee D, Lahiry S, Sinha R (2017) Association of depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a single centre experience. Int J Res Med Sci 5:3600–3604. https://doi.org/10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20173570

Wilson JM, Lee J, Fitzgerald HN et al (2020) Job insecurity and financial concern during the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with worse mental health. J Occup Environ Med 62:686–691. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000001962

Verstappen SMM (2015) Rheumatoid arthritis and work: the impact of rheumatoid arthritis on absenteeism and presenteeism. Best Pract Res ClinRheumatol 29:495–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2015.06.001

Endstrasser F, Braito M, Linser M et al (2020) The negative impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on pain and physical function in patients with end-stage hip or knee osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Sports TraumatolArthrosc 28:2435–2443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-020-06104-3

Brown TS, Bedard NA, Rojas EO et al (2020) The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on electively scheduled hip and knee arthroplasty patients in the United States. J Arthroplasty 35:S49–S55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.052

Matcham F, Ali S, Irving K et al (2016) Are depression and anxiety associated with disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis? A prospective study BMC prospective study. BMC MusculoskeletDisord 17:155. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-016-1011-1

Bai B, Chen M, Fu L et al (2020) Quality of life and influencing factors of patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Northeast China. Health Qual Life Outcomes 18:119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01355-7

Kojima M, Kojima T, Suzuki S et al (2009) Depression, inflammation, and pain in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 61:1018–1024. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.24647

Matcham F, Ali S, Hotopf M, Chalder T (2015) Psychological correlates of fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. ClinPsychol Rev 39:16–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.03.004

Ang DC, Choi H, Kroenke K, Wolfe F (2005) Comorbid depression is an independent risk factor for mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 32:1013–1019 (PMID: 15940760)

Boyden SD, Hossain IN, Wohlfahrt A, Lee YC (2016) Non-inflammatory causes of pain in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. CurrRheumatol Rep 18:30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-016-0581-0

Ramiro S, Radner H, van der Heijde D et al (2011) Combination therapy for pain management in inflammatory arthritis (rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, other spondyloarthritis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008886.pub2

Whittle SL, Richards BL, Husni E, Buchbinder R (2011) Opioid therapy for treating rheumatoid arthritis pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003113.pub3

Kojima M, Kojima T, Suzuki S et al (2014) Alexithymia, depression, inflammation, and pain in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 66:679–686. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22203

Baumeister H, Balke K, Härter M (2005) Psychiatric and somatic comorbidities are negatively associated with quality of life in physically ill patients. J ClinEpidemiol 58:1090–1100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.03.011

DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW (2000) Depression Is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med 160:2101. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101

Pratt LA, Brody DJ (2010) Depression and smoking in the U.S. household population aged 20 and over, 2005–2008. NCHS Data Brief 1–8. PMID: 20604991

Curtis R, Groarke A, Coughlan R, Gsel A (2004) The influence of disease severity, perceived stress, social support and coping in patients with chronic illness: a 1 year follow up. Psychol Health Med 9:456–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354850042000267058

Evers A, Kraaimaat F, Geenen R, Jacobs J, Bijlsma J (2003) Pain coping and social support as predictors of long-term functional disability and pain in early rheumatoid arthritis. Behav Res Ther 41:1295–1310. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00036-6

Morris A, Yelin EH, Wong B, Katz PP (2008) Patterns of psychosocial risk and long-term outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis. Psychol Health Med 13:529–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500801927113

Curtis R, Groarke A, Coughlan R, Gsel A (2005) Psychological stress as a predictor of psychological adjustment and health status in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Patient EducCouns 59:192–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2004.10.015

McBain H, Shipley M, Newman S (2013) The impact of appearance concerns on depression and anxiety in rheumatoid arthritis. Musculoskeletal Care 11:19–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/msc.1020

Dekkers JC, Geenen R, Evers AWM et al (2001) Biopsychosocial mediators and moderators of stress–health relationships in patients with recently diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 45:307–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/1529-0131(200108)45:4%3c307::AID-ART342%3e3.0.CO;2-0

Strating MMH, Suurmeijer TPBM, Schuur WHV (2006) Disability, social support, and distress in rheumatoid arthritis: results from a thirteen-year prospective study. Arthritis Care Res 55:736–744. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.22231

Bonfá E, Gossec L, Isenberg DA et al (2021) How COVID-19 is changing rheumatology clinical practice. Nat Rev Rheumatol 17:11–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41584-020-00527-5

Naveen R, Sundaram TG, Agarwal V, Gupta L (2021) Teleconsultation experience with the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: a prospective observational cohort study during the COVID-19 pandemic. RheumatolInt 41:67–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04737-8

Gupta L, Lilleker JB, Agarwal V et al (2020) COVID-19 and myositis – unique challenges for patients. Rheumatology. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keaa610

Gupta L, Kharbanda R, Agarwal V et al (2021) Patient perspectives on the effect of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on patients with systemic sclerosis: an international patient survey. JCR J ClinRheumatol 27:31–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/RHU.0000000000001681

Gupta L, Misra DP, Agarwal V, et al (2020) Response to: ‘Telerheumatology in COVID-19 era: a study from a psoriatic arthritis cohort’ by Costa et al. Ann Rheum Dis. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217953

Currie CL, Larouche R, Voss ML et al (2020) The impact of eHealth group interventions on the mental, behavioral, and physical health of adults: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev 9:217. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01479-3

Misra DP, Agarwal V (2020) To act or to wait for the evidence: ethics in the time of covid-19! Indian J Rheumatol 15:3–4. https://doi.org/10.4103/injr.injr_53_20

Ahmed S, Gasparyan AY, Zimba O (2021) Comorbidities in rheumatic diseases need special consideration during the COVID-19 pandemic. RheumatolInt. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04764-5

Lin EHB, Katon W, Von Korff M et al (2003) Effect of improving depression care on pain and functional outcomes among older adults with arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 290:2428. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.290.18.2428

T S, R G, J.a.p JJWG and DS (2014) Psychological Factors Associated with Response to Treatment in Rheumatoid Arthritis. In: Curr. Pharm. Des. https://www.eurekaselect.com/124107/article. Accessed 13 Jan 2021

Goel A, Gupta L (2020) Social media in the times of COVID-19. JCR J ClinRheumatol 26:220–223. https://doi.org/10.1097/RHU.0000000000001508

Brady SM, Fenton SAM, Metsios GS et al (2021) Different types of physical activity are positively associated with indicators of mental health and psychological wellbeing in rheumatoid arthritis during COVID-19. RheumatolInt 41:335–344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04751-w

van Zanten JJCSV, Fenton SAM, Brady S, et al (2020) Mental health and psychological wellbeing in rheumatoid arthritis during COVID-19 – can physical activity help? Mediterr J Rheumatol 31:284. https://doi.org/10.31138/mjr.31.3.284

Agarwal V, Sharma S, Gupta L et al (2020) COVID-19 and psychological disaster preparedness – an unmet need. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 14:387–390. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.219

Geenen R, Overman CL, Christensen R et al (2018) EULAR recommendations for the health professional’s approach to pain management in inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 77:797–807. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212662

Richards BL, Whittle SL, Buchbinder R (2012) Muscle relaxants for pain management in rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008922.pub2

American Geriatrics Society (2019) Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am GeriatrSoc 67:674–694. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15767

Ruhaila AR, Chong HC (2018) Self-reported symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress among patients with rheumatoid arthritis in a Malaysian rheumatology centre - prevalence and correlates. Med J Malaysia 73:226–232 (PMID: 30121685)

Vallerand IA, Lewinson RT, Frolkis AD et al (2018) Depression as a risk factor for the development of rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. RMD Open 4:e000670. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000670

Marrie RA, Walld R, Bolton JM et al (2017) Increased incidence of psychiatric disorders in immune-mediated inflammatory disease. J Psychosom Res 101:17–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.07.015

Marrie RA, Walld R, Bolton JM et al (2018) Psychiatric comorbidity increases mortality in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 53:65–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2018.06.001

Gåfvels C, Hägerström M, Rane K et al (2016) Depression and anxiety after 2 years of follow-up in patients diagnosed with diabetes or rheumatoid arthritis. Health Psychol Open 3:2055102916678107. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055102916678107

Demmelmaier I, Pettersson S, Nordgren B et al (2018) Associations between fatigue and physical capacity in people moderately affected by rheumatoid arthritis. RheumatolInt 38:2147–2155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-018-4140-z

Wang SL, Chang CH, Hu LY, Tsai SJ, Yang AC, You Z-H (2014) Risk of developing depressive disorders following rheumatoid arthritis: a nationwide population-based study. PLoS ONE 9:e107791. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0107791

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Connecting Researchers and Dr Malke Asaad for their help with this work.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CRediT author statement: AB:—Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation, Visualization, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, LG:—Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Writing—Reviewing & Editing, Supervision. MKC—Investigation, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bhatia, A., KC, M. & Gupta, L. Increased risk of mental health disorders in patients with RA during the COVID-19 pandemic: a possible surge and solutions. Rheumatol Int 41, 843–850 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-021-04829-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-021-04829-z