Abstract

Comorbidities in rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) not only increase morbidity and mortality but also confound disease activity, limit drug usage and increase chances of severe infections or drug-associated adverse effects. Most RMDs lead to accelerated atherosclerosis and variable manifestations of the metabolic syndrome. Literature on COVID-19 in patients with RMDs, and the effects of various comorbidities on COVID-19 was reviewed. The initial data of COVID-19 infections in RMDs have not shown an increased risk for severe disease or the use of different immunosuppression. However, there are some emerging data that patients with RMDs and comorbidities may fare worse. Various meta-analyses have reiterated that pre-existing hypertension, cardiovascular disease, stroke, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, heart failure, lung disease or obesity predispose to increased COVID-19 mortality. All these comorbidities are commonly encountered in the various RMDs. Presence of comorbidities in RMDs pose a greater risk than the RMDs themselves. A risk score based on comorbidities in RMDs should be developed to predict severe COVID-19 and death. Additionally, there should be active management of such comorbidities to mitigate these risks. The pandemic must draw our attention towards, and not away from, comorbidities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Comorbidities are additional disease states or organ involvement that exist parallel to an index disease, and can delay diagnosis, confound the assessment of disease status, jeopardise treat-to-target strategies and reduce the quality of life or increase mortality [1]. Rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) are chronic conditions that accrue damage as well as comorbidities over the years. An initiative from the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) stresses six significant comorbidities that need to be addressed in RMDs: ischaemic cardiovascular diseases, depression, infections, gastrointestinal diseases, osteoporosis and malignancies [2].

The most common comorbidity is likely cardiovascular. The risk of a myocardial event is at least 50% higher in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, gout and psoriatic arthritis than for the general population [3]. The risk is also higher for patients with osteoarthritis, and possibly for those with ankylosing spondylitis [3]. In chronic painful conditions like arthritis, there is catastrophising and thus, concomitant depression arising out of such inadept defence mechanisms [4]. Also, the chronic inflammation predisposes to neuroendocrine suppression, fatigue, sarcopenia, osteopenia and possibly a lean variant of the metabolic syndrome (“cachectic obesity”) [5]. A meta-analysis has shown that patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are at higher risk for lymphoma and lung malignancies [6]. All these comorbidities including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, osteoporosis, neoplasms, depression, and infections are often sub-optimally diagnosed and managed [2].

Comorbidities in RMDs have gained an extreme significance as they may be associated with increased risks of hospitalisation and death in the wake of the coronavirus-19 (COVID-19) pandemic. Preliminary data from patients with RMDs in Spain have shown that the presence of comorbidities as well as disease activity were associated with severe COVID-19 and death [7]. The initial cohort of patients with RMDs who had developed COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, included 17 patients, of which at least nine had comorbidities and one of these patients expired. Follow-up interviews of the 16 discharged patients revealed that 10 of them had discontinued or changed their rheumatology drugs [8]. Similarly, the report of the first 600 patients in the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance (C19-GRA) physician-reported registry also reiterated that age above 65 years and presence of comorbidities were more likely to be hospitalised [9].

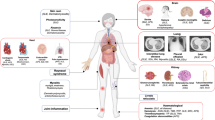

Therefore, it is important to appraise the various comorbidities in RMD in the context of risk for COVID-19, and also, to anticipate how the pandemic influences the management and the prevention of comorbidities in RMDs. Closely entwined is the question of whether exposure to the severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) in patients with RMDs would increase the risk of future comorbidities (Fig. 1).

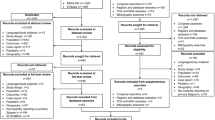

Search strategies

Searches were carried out on MEDLINE/PubMed and Scopus in the first week of Oct 2020 for the literature on COVID-19 in RMD patients as per standard recommendations [10]. The common keywords used for the first search were “rheumatic disease”, “inflammatory arthritis”, “rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases” in various combinations with “COVID-19” or “SARS-CoV-2”. The second search included “COVID-19”or “SARS-CoV-2” with different combinations with “comorbidities”, “metabolic syndrome”, “diabetes”, “hypertension”, “lung disease”, “cardiovascular disease”, “stroke” and “myocardial infarction”. The third search used “rheumatic disease”, “inflammatory arthritis”, or “rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases” with the different comorbidities keywords included in the second search. The searches were updated in the third week of November to include any articles published since the initial searches.

COVID-19 in RMD patients

In the initial data from China, there were 21 patients with RMDs and length of hospital stay was similar to those without RMDs [11]. A retrospective study from Spain has shown a higher prevalence of hospital diagnosed COVID-19 was more in patients on biologicals but in those on conventional DMARDs [12]. The results are summarised in Table 1. Telephonic or internet-based surveys estimating the incidence of infection without mentioning comorbidities have not been included in this table. Studies having higher co-morbidities seem to have more severe cases, often attributing it to the presence of RMDs. However, in studies with lower co-morbidities, there appears to be no difference of COVID-19 severity in RMDs and general populations. For patients with RMDs, prior knowledge about avoiding infections may play a role in reducing SARS-CoV-2 infection [13].

Comorbidities and death in COVID-19

In one of the first retrospective cohorts published from Wuhan, China, almost 50% of patients hospitalised with COVID-19 had comorbidities [36]. In the first 200 patients admitted in New York, the three most common comorbidities were hypertension (76%), hyperlipidemia (46.2%), and diabetes (39.5%) [37]. In an analysis of 3626 patients regarding the effects of race on COVID-19 outcomes, a higher score on the Charlson Comorbidity Index was associated with increased rates of hospitalisation [38]. Thus, comorbidities are common in patients with COVID-19. Table 2 summarises various meta-analyses looking at the associations of multiple comorbidities with mortality or severe disease in COVID-19.

One meta-analysis looking at patients with autoimmune diseases developing COVID-19 found no association with severe disease (3 studies, 1276 patients, OR = 1.21, 95% CI: 0.58–2.50, p = 0.79) or with mortality (3 studies, 835 patients, OR = 1.31, 95% CI: 0.33–5.20, p = 0.95) [56]. However, it should be kept in mind that the RMDs may be only a part of all autoimmune diseases, and the numbers are too small to analysis those with comorbidities.

Comorbidities in RMD that may predispose to severe COVID-19 and death

The different co-morbidities in various RMDs have different prevalence. Patients with difficult to control diseases often have higher comorbidities [57]. The most common comorbidities in each are enumerated in Table 3. Paediatrics patients often have limited comorbidities, and a systematic review has identified only one single child with RMD who had acquired COVID-19 [58].

Metabolic syndrome

Rheumatoid arthritis is associated with most facets of the metabolic syndrome. A meta-analysis has shown that the presence of RA is a risk factor for developing diabetes [97]. The system inflammation in RA, along with the use of glucocorticoids, has been implicated in the development of insulin resistance in RA [98]. This can be closely associated with obesity. At least a quarter of RA patients are overweight (BMI > 25) [62]. Besides being a direct risk factor, it also contributes indirectly by increasing disease activity and making remission more difficult to achieve [99]. Hypertension can be seen in around 50% of RA and is possibly more in patients with resistant disease [57]. Also, underdiagnosis and undertreatment of hypertension and dyslipidaemia in RA are reported [63]. The relationship of psoriatic arthritis with metabolic syndrome is stronger with common mechanistic pathways leading to both [100]. The cardiovascular risks of various rheumatic diseases have been explored in depth in various reviews [101, 102].

Accelerated atherothrombosis at premature age

The metabolic syndrome, as well as the pro-inflammatory state, leads to accelerated thrombosis. COVID-19 is intrinsically a pro-thrombotic state [103]. Thus, the risk of thrombosis may be multiplied in the setting of COVID-19.

Interstitial lung diseases

Amongst lung diseases, interstitial diseases (ILD) have the highest association with rheumatic disease. In RA, it is reported to have a prevalence from 1–60% depending on the methodology used [67]. Many of these patients may not be symptomatic, and only a proportion will have progressive lung disease. However, it is not known whether this will predispose to severe lung COVID-19. ILD are often a major concern in patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc) and with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM). ILD is the most frequent cause of death in SSc [104]. Registry data show around 40–50% of SSc patients are documented to have ILD [105]. A similar proportion of patients with mixed connective tissue disorder have ILD that is slowly progressive and increases the mortality rate [106]. Also, in the spectrum of IIM, the presence of ILD has been associated with 50% excess mortality [107]. ILD in Sjogren is reported from 8–35% with a 5-year survival of 84% [93, 108, 109].

Chronic kidney disease

Patients with lupus nephritis may develop chronic kidney damage including interstitial fibrosis and glomerulosclerosis. Similarly, patients with Sjogren and long-standing RA may also develop features of chronic kidney disease (CKD). A meta-analysis of cohort studies has shown that patients with RA have a higher incidence of developing CKD [110]. Though previously, it was attributable to the high use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and uncontrolled inflammation (leading to amyloidosis), currently, it is more likely to be associated with accelerated atherosclerosis [111]. Though the mortality in lupus has come down drastically in the last 2 to 3 decades, renal impairment is still seen in up to 40% of patients [85]. Scleroderma renal crisis, though uncommon, is the leading cause of renal transplantation in SSc patients, and 5 years mortality after transplant is 82.5% [112]. It is well known that COVID-19 can directly precipitate acute kidney injury (AKI) and presence of CKD is a poor prognostic marker.

Effects of depression

The association between inflammatory rheumatic diseases and depression is well established. A meta-analysis has shown that depression is prevalent in at least one-third of patients with RA [113].

Immunomodulatory therapy seems to improve mental parameters independent of improvement in physical disease activity [114]. Conversely, it is expected that depression would also alter immune parameters in an individual. It can alter the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and sympathetic outflow [4]. Depression is associated with immune dysregulation, independent of RMDs [115]. This may predispose to infections and possibly even severe COVID-19. In mice models, it has been shown that repeated social defeat leads to immune suppression [116]. Though there may be a risk of confounding by indication, a cohort of 59,301 people followed up for 14.8 years has shown that those with depression have a higher incidence of blood-stream infections [117].

Risk of infections

RMDs are independently associated with the risk of infections [118]. The various disease-modifying anti-rheumatoid drugs (DMARDs) are immunomodulatory agents. Especially the use of targeted synthetic and biological DMARDs possibly predispose to a higher rate of infections including opportunistic infections [119]. Though rituximab has been implicated to have a higher risk of infections as compared to other biologicals, a meta-analysis has shown no difference [120].

People with RMDs usually have poorer compliance with vaccination [121] though they are often at increased risks for various infections including pneumococcal, meningococcal, herpetic and other vaccine-preventable infections [122].

Risk stratification for severe COVID-19 and death in RMDs

Quantifying the risks for severe COVID-19 and mortality is required. A risk score to predict this will need to include the number of comorbidities providing a weightage score based on the severity and duration of each. The previous history of infections, hypogammaglobulinemia, hospitalisations should also be included in the score. Current immunosuppressive drugs including cumulative exposure to steroids may also be important predictors for severe COVID-19 in the presence of comorbidities [9].

Management of comorbidities to reduce risk of severe COVID-19 and death

Management of hypertension, diabetes and coronary artery disease can help in reducing mortality in COVID-19. Currently, there is ample evidence that the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and ACE-receptor blockers in patients with hypertension help in reducing both COVID-19 severity and mortality [123]. A good number of meta-analyses have been carried out looking at the effects of renin–angiotensin inhibitors in COVID-19, and now there is sufficient proof that the use of ACE-inhibitors for any indication reduces mortality in COVID-19 [124].

Statins have been shown to be able to reduce cardiovascular mortality in RA [125]. There is a biological basis for statins in reducing atherosclerotic disease in other RMDs like lupus as well [126]. Statins have also been proposed for COVID-19 [127], and there is emerging evidence that statins can reduce mortality in COVID-19. Analysis of hospital data from China has shown that statin treatment was associated with lower mortality (adjusted hazard ratio of 0.63, 95% CI 0.48–0.84, p = 0.001) compared to non-statin users [128].

Hydroxychloroquine (HCQS) is a cornerstone drug for lupus and has potential role against atherothrombosis via downregulation of Toll-like receptor signalling, cytokine production, T cell and monocyte activation [129]. Rodent models have demonstrated beneficial effects on endothelial dysfunction [130]. Though not established as a standard of care in vasculitis yet, it has been shown to be helpful in anti-neutrophilic neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis, IgA vasculitis, Takayasu's arteritis and polyarteritis nodosa [131]. A significant part of this action may be due to its potential anti-endothelial dysfunction and anti-thrombotic mechanisms in vasculitis. Endothelial dysfunction with ‘endotheliitis’ plays a significant part in COVID-19 pathogenesis [132]. It has been shown that hydroxychloroquine does not protect from COVID-19 in rheumatology patients [133]. However, higher disease activity in RMDs is independently associated with higher mortality in COVID-19. HCQS should not be stopped in patients already taking them. There is speculation with the demonstration of anti-phospholipid antibodies in COVID-19 patients [134] that these antibodies may have a pathological role. If so, there can be a strong case for HCQS in preventing thrombosis in COVID-19.

Lower vitamin D levels have been associated with more severe COVID-19 [135]. Serum levels of vitamin D have been suggested as a biomarker for outcomes in COVID-19 [136]. The association of mortality with obesity may have low vitamin D as a confounding factor [137]. Many RMDs have low serum vitamin D levels [138]. There is some preliminary evidence of the benefit of vitamin D in RMDs [139]. It needs to be seen whether vitamin D will also help in RMD patients with COVID-19.

Many patients with RMDs receive vitamin D supplementation for osteopenia or osteoporosis. It remains to be seen if this influences the outcomes of COVID-19. One study has shown that people receiving denosumab, zoledronate and duloxetine had a negative association with COVID-19 incidence [140]. This was not true for vitamin D supplementation. It is difficult to interpret the study now and more evidence including the validations of these findings is required.

Maintaining physical health through activity is an essential part of the battle against the pandemic. It is important not to marginalise the benefits of physical activity [137]. Social distancing should not mean any patient has to be isolated at home without any activity like walking. Even staying at home, there is scope for introducing interventions like resistance training, respiratory muscle training (including deep breathing exercises) with aerobics wherever feasible [141]. The breathing exercises described as a part of Yoga may help both respiratory muscles as well have short-term favourable outcomes on depression [142].

Effect of COVID-19 on comorbidities in RMDs

There are case reports of several new rheumatic diseases being diagnosed after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Some may be atypical features of COVID-19 itself while others might be simmering RMDs unmasked during the inflammation of COVID-19. However, COVID-19 may itself also initiate autoimmune diseases including RMDs [143]. One immune-mediated syndrome is Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) [144]. The inflammatory pathways involved in COVID-19 have remarkable overlap with those of rheumatoid arthritis [145]. However, COVID-19 has not been shown to precipitate arthritis except case reports [146, 147] that are possibly the exceptions that prove the rule. Similarly, there is little evidence to suggest that COVID-19 can worsen pre-existing arthritis [148].

COVID-19 has been shown to precipitate cardiomyopathy, and lung fibrosis had may have more tremendous implications for patients pre-existing RMDs. Magnetic resonance imaging of patients recovered from COVID-19 has shown active cardiac involvement in 60%, independent of pre-existing conditions and severity of COVID-19 [149]. A similar study had also been reported from China [150]. Post-COVID-19 pulmonary fibrosis is likely to be associated with older age, the severity of pneumonia, and background lung disease [151]. Patients with RMDs predisposing to lung pathology may have higher risks of post-COVID-19 fibrosis.

In data from Switzerland, there was no increase in disease activity of RMDs in the short term since the onset of the pandemic. However, drug non-compliance has increased [152]. This might lead to increased flares in the near future. This can also increase the inflammatory burden and add to cardiovascular risks. Thus, patients with RMDs may have an increased risk of developing comorbidities after exposure to SARS-CoV-2.

Implications for the rheumatologist

The pandemic has forced an unprecedented shift to online platforms and virtual consultations. Now patient-reported outcomes have taken antecedence over physician assessments [153]. However, these will focus more on the primary manifestations of diseases and are likely to relegate comorbidities to the background. Comorbidities, already being sub-optimally managed [2], maybe neglected further. Newer comorbidities may be missed on teleconsultations.

Many drugs used in rheumatology have been proposed for COVID-19 [154]. However, these have not shown any evidence of benefit to date [155]. The small benefit of these drugs may be offset by the presence of the various comorbidities in RMDs. Thus, unless comorbidities are addressed, we may be missing out on much relevant information.

Again, the pandemic may influence drug compliance due to unavailability of drugs, missing appointments with rheumatologists, or even just a fear of using ‘immunosuppressant’ drugs. This itself might lead to flares and increased comorbidities that might be attributed as a direct pathobiological effect of COVID-19 [156].

Conclusion

Thus, there is a need to stratify RMDs as per the presence and number of comorbidities. This will help physicians predict risk for severe COVID-19 as well as future overall outcomes. It may also have implications on prioritising candidates for future COVID-19 vaccines.

The knowledge about various comorbidities and how to tackle these has expanded in the last couple of decades, but the current pandemic threatens to take the focus away. It is crucial to incorporate protocols to address them during consultations, particularly teleconsultations. Holistic management will only be possible when we focus on the patients as a whole, and not just what is mandated by the primary disease targets.

References

Moltó A, Dougados M (2014) Comorbidity indices. Clin Exp Rheumatol 32:S131-134

Baillet A, Gossec L, Carmona L et al (2016) Points to consider for reporting, screening for and preventing selected comorbidities in chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases in daily practice: a EULAR initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 75:965–973. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209233

Schieir O, Tosevski C, Glazier RH et al (2017) Incident myocardial infarction associated with major types of arthritis in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 76:1396–1404. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210275

Edwards RR, Cahalan C, Calahan C et al (2011) Pain, catastrophizing, and depression in the rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol 7:216–224. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2011.2

Straub RH (2017) The brain and immune system prompt energy shortage in chronic inflammation and ageing. Nat Rev Rheumatol 13:743–751. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2017.172

Simon TA, Thompson A, Gandhi KK et al (2015) Incidence of malignancy in adult patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther 17:212. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-015-0728-9

Santos CS, Morales CM, Álvarez ED et al (2020) Determinants of COVID-19 disease severity in patients with underlying rheumatic disease. Clin Rheumatol 39:2789–2796. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05301-2

Onuora S (2020) New data emerging on outcomes for patients with COVID-19 and rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol 16:407. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41584-020-0463-8

Gianfrancesco M, Hyrich KL, Al-Adely S et al (2020) Characteristics associated with hospitalisation for COVID-19 in people with rheumatic disease: data from the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance physician-reported registry. Ann Rheum Dis 79:859–866. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217871

Gasparyan AY, Ayvazyan L, Blackmore H, Kitas GD (2011) Writing a narrative biomedical review: considerations for authors, peer reviewers, and editors. Rheumatol Int 31:1409–1417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-011-1999-3

Ye C, Cai S, Shen G et al (2020) Clinical features of rheumatic patients infected with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Ann Rheum Dis 79:1007–1013. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217627

Pablos JL, Abasolo L, Alvaro-Gracia JM et al (2020) Prevalence of hospital PCR-confirmed COVID-19 cases in patients with chronic inflammatory and autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis 79:1170–1173. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217763

Kipps S, Paul A, Vasireddy S (2020) Incidence of COVID-19 in patients with rheumatic disease: is prior health education more important than shielding advice during the pandemic? Clin Rheumatol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05494-6

D’Silva KM, Serling-Boyd N, Wallwork R et al (2020) Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and rheumatic disease: a comparative cohort study from a US ‘hot spot.’ Ann Rheum Dis 79:1156–1162. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217888

Sanchez-Piedra C, Diaz-Torne C, Manero J et al (2020) Clinical features and outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with rheumatic diseases treated with biological and synthetic targeted therapies. Ann Rheum Dis 79:988–990. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217948

Freites Nuñez DD, Leon L, Mucientes A et al (2020) Risk factors for hospital admissions related to COVID-19 in patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217984

Pablos JL, Galindo M, Carmona L et al (2020) Clinical outcomes of hospitalised patients with COVID-19 and chronic inflammatory and autoimmune rheumatic diseases: a multicentric matched cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218296

Nuño L, Navarro MN, Bonilla G et al (2020) Clinical course, severity and mortality in a cohort of patients with COVID-19 with rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218054

Scirè CA, Carrara G, Zanetti A et al (2020) COVID-19 in rheumatic diseases in Italy: first results from the Italian registry of the Italian Society for Rheumatology (CONTROL-19). Clin Exp Rheumatol 38:748–753

Cheng C, Li C, Zhao T et al (2020) COVID-19 with rheumatic diseases: a report of 5 cases. Clin Rheumatol 39:2025–2029. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05160-x

Quartuccio L, Valent F, Pasut E et al (2020) Prevalence of COVID-19 among patients with chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases treated with biologic agents or small molecules: a population-based study in the first two months of COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Joint Bone Spine 87:439–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2020.05.003

Hasseli R, Mueller-Ladner U, Schmeiser T et al (2020) National registry for patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases (IRD) infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Germany (ReCoVery): a valuable mean to gain rapid and reliable knowledge of the clinical course of SARS-CoV-2 infections in patients with IRD. RMD Open 6:e001332. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001332

Coskun Benlidayi I, Kurtaran B, Tirasci E, Guzel R (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a patient with ankylosing spondylitis treated with secukinumab: a case-based review. Rheumatol Int 40:1707–1716. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04635-z

Montero F, Martínez-Barrio J, Serrano-Benavente B et al (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in autoimmune and inflammatory conditions: clinical characteristics of poor outcomes. Rheumatol Int 40:1593–1598. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04676-4

Loarce-Martos J, García-Fernández A, López-Gutiérrez F et al (2020) High rates of severe disease and death due to SARS-CoV-2 infection in rheumatic disease patients treated with rituximab: a descriptive study. Rheumatol Int 40:2015–2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04699-x

So H, MAK JW-Y, SO J et al (2020) Incidence and clinical course of COVID-19 in patients with rheumatologic diseases: a population-based study. Semin Arthritis Rheum 50:885–889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.07.012

Sharmeen S, Elghawy A, Zarlasht F, Yao Q (2020) COVID-19 in rheumatic disease patients on immunosuppressive agents. Semin Arthritis Rheum 50:680–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.05.010

Michelena X, Borrell H, López-Corbeto M et al (2020) Incidence of COVID-19 in a cohort of adult and paediatric patients with rheumatic diseases treated with targeted biologic and synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs. Semin Arthritis Rheum 50:564–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.05.001

Fredi M, Cavazzana I, Moschetti L et al (2020) COVID-19 in patients with rheumatic diseases in northern Italy: a single-centre observational and case–control study. Lancet Rheumatol 2:e549–e556. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30169-7

Zhong J, Shen G, Yang H et al (2020) COVID-19 in patients with rheumatic disease in Hubei province, China: a multicentre retrospective observational study. Lancet Rheumatol 2:e557–e564. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30227-7

Pistone A, Tant L, Soyfoo MS (2020) Clinical course of COVID-19 infection in inflammatory rheumatological patients: a monocentric Belgian experience. Rheumatol Adv Pract 4:rkaa055. https://doi.org/10.1093/rap/rkaa055

Tiendrébéogo WJS, Kaboré F, Diendéré EA, Ouedraogo DD (2020) Case series of chronic inflammatory rheumatic disease patients infected by coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Case Rep Rheumatol 2020:8860492. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8860492

Lwin M, Holroyd C, Wallis D et al (2020) Does COVID-19 cause an increased risk of hospitalisation or death in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases treated with bDMARDs or tsDMARDs? Rheumatol Adv Pract. https://doi.org/10.1093/rap/rkaa061

Murray K, Quinn S, Turk M et al (2020) COVID-19 and rheumatic musculoskeletal disease patients: infection rates, attitudes and medication adherence in an Irish population. Rheumatology (Oxford) keaa694. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keaa694

Costantino F, Bahier L, Tarancón LC et al (2020) COVID-19 in French patients with chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases: clinical features, risk factors and treatment adherence. Joint Bone Spine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2020.105095

Zhou F, Yu T, Du R et al (2020) Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 395:1054–1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3

Palaiodimos L, Kokkinidis DG, Li W et al. (2020) Severe obesity, increasing age and male sex are independently associated with worse in-hospital outcomes, and higher in-hospital mortality, in a cohort of patients with COVID-19 in the Bronx New York. Metabolism 108:154262. DOI: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154262

Price-Haywood EG, Burton J, Fort D, Seooane L (2020) Hospitalization and mortality among black patients and white patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med 382:2534–2543. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa2011686

Ssentongo P, Ssentongo AE, Heilbrunn ES et al (2020) Association of cardiovascular disease and 10 other pre-existing comorbidities with COVID-19 mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 15:e0238215. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238215

Zheng Z, Peng F, Xu B et al (2020) Risk factors of critical and mortal COVID-19 cases: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Infect 81:e16–e25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.021

Pranata R, Huang I, Lim MA et al (2020) Impact of cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases on mortality and severity of COVID-19-systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis Off J Natl Stroke Assoc 29:104949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.104949

Yang J, Zheng Y, Gou X et al (2020) Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis 94:91–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017

Li B, Yang J, Zhao F et al (2020) Prevalence and impact of cardiovascular metabolic diseases on COVID-19 in China. Clin Res Cardiol 109:531–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-020-01626-9

Alqahtani JS, Oyelade T, Aldhahir AM et al (2020) Prevalence, severity and mortality associated with COPD and smoking in patients with COVID-19: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 15:e0233147. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233147

Huang I, Lim MA, Pranata R (2020) Diabetes mellitus is associated with increased mortality and severity of disease in COVID-19 pneumonia - a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Diabetes Metab Syndr 14:395–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.018

Wu Z, Tang Y, Cheng Q (2020) Diabetes increases the mortality of patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis. Acta Diabetol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-020-01546-0

Roncon L, Zuin M, Rigatelli G, Zuliani G (2020) Diabetic patients with COVID-19 infection are at higher risk of ICU admission and poor short-term outcome. J Clin Virol Off Publ Pan Am Soc Clin Virol 127:104354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104354

Fadini GP, Morieri ML, Longato E, Avogaro A (2020) Prevalence and impact of diabetes among people infected with SARS-CoV-2. J Endocrinol Invest 43:867–869. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-020-01236-2

Barrera FJ, Shekhar S, Wurth R et al (2020) Prevalence of diabetes and hypertension and their associated risks for poor outcomes in COVID-19 patients. J Endocr Soc 4:102. https://doi.org/10.1210/jendso/bvaa102

Kumar A, Arora A, Sharma P et al (2020) Is diabetes mellitus associated with mortality and severity of COVID-19? A meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr 14:535–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.044

Liang X, Shi L, Wang Y et al (2020) The association of hypertension with the severity and mortality of COVID-19 patients: Evidence based on adjusted effect estimates. J Infect 81:e44–e47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.060

Zhang J, Wu J, Sun X et al (2020) Association of hypertension with the severity and fatality of SARS-CoV-2 infection: a meta-analysis. Epidemiol Infect 148:e106. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095026882000117X

Zuin M, Rigatelli G, Zuliani G et al (2020) Arterial hypertension and risk of death in patients with COVID-19 infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect 81:e84–e86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.059

Pranata R, Lim MA, Huang I et al (2020) Hypertension is associated with increased mortality and severity of disease in COVID-19 pneumonia: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. J Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst JRAAS 21:1470320320926899 doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1470320320926899

Hussain A, Mahawar K, Xia Z et al (2020) Obesity and mortality of COVID-19. Meta-analysis Obes Res Clin Pract 14:295–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orcp.2020.07.002

Liu M, Gao Y, Zhang Y et al (2020) The association between severe or dead COVID-19 and autoimmune diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect 81:e93–e95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.065

Batko B, Urbański K, Świerkot J et al (2019) Comorbidity burden and clinical characteristics of patients with difficult-to-control rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 38:2473–2481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04579-1

Batu ED, Özen S (2020) Implications of COVID-19 in pediatric rheumatology. Rheumatol Int 40:1193–1213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04612-6

Kerekes G, Nurmohamed MT, González-Gay MA et al (2014) Rheumatoid arthritis and metabolic syndrome. Nat Rev Rheumatol 10:691–696. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2014.121

Hallajzadeh J, Safiri S, Mansournia MA et al (2017) Metabolic syndrome and its components among rheumatoid arthritis patients: a comprehensive updated systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 12:e0170361. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170361

Castro LL, Lanna CCD, Rocha MP et al (2018) Recognition and control of hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int 38:1437–1442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-018-4084-3

de Resende Guimarães MFB, Rodrigues CEM, Gomes KWP et al (2019) High prevalence of obesity in rheumatoid arthritis patients: association with disease activity, hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes, a multi-center study. Adv Rheumatol 59:44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42358-019-0089-1

van Breukelen-van der Stoep DF, van Zeben D, Klop B et al (2016) Marked underdiagnosis and undertreatment of hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 55:1210–1216. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kew039

Pappas DA, Nyberg F, Kremer JM et al (2018) Prevalence of cardiovascular disease and major risk factors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a multinational cross-sectional study. Clin Rheumatol 37:2331–2340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-018-4113-3

Albrecht K, Luque Ramos A, Hoffmann F et al (2018) High prevalence of diabetes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from a questionnaire survey linked to claims data. Rheumatology (Oxford) 57:329–336. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kex414

Norton S, Koduri G, Nikiphorou E et al (2013) A study of baseline prevalence and cumulative incidence of comorbidity and extra-articular manifestations in RA and their impact on outcome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 52:99–110. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kes262

Spagnolo P, Lee JS, Sverzellati N et al (2018) The lung in rheumatoid arthritis: focus on interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheumatol 70:1544–1554. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.40574

Crowson CS, Rollefstad S, Ikdahl E et al (2018) Impact of risk factors associated with cardiovascular outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 77:48–54. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211735

Ortolan A, Lorenzin M, Tadiotto G et al (2019) Metabolic syndrome, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and liver stiffness in psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis patients. Clin Rheumatol 38:2843–2850. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04646-7

Özkan SG, Yazısız H, Behlül A et al (2017) Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and degree of cardiovascular disease risk in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Eur J Rheumatol 4:40–45. https://doi.org/10.5152/eurjrheum.2017.16052

Caso F, Del Puente A, Oliviero F et al (2018) Metabolic syndrome in psoriatic arthritis: the interplay with cutaneous involvement. Evidences from literature and a recent cross-sectional study. Clin Rheumatol 37:579–586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-017-3975-0

Favarato MH, Mease P, Gonçalves CR et al (2014) Hypertension and diabetes significantly enhance the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 32:182–187

Queiro R, Lorenzo A, Tejón P et al (2019) Hypertension is associated with increased age at the onset of psoriasis and a higher body mass index in psoriatic disease. Clin Rheumatol 38:2063–2068. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04519-z

Queiro R, Lorenzo A, Tejón P et al (2019) Obesity in psoriatic arthritis: comparative prevalence and associated factors. Medicine (Baltimore) 98:e16400. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000016400

Radner H, Lesperance T, Accortt NA, Solomon DH (2017) Incidence and prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors among patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, or psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 69:1510–1518. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23171

Dubreuil M, Rho YH, Man A et al (2014) Diabetes incidence in psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis: a UK population-based cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 53:346–352. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ket343

Queiro R, Lorenzo A, Pardo E et al (2018) Prevalence and type II diabetes-associated factors in psoriatic arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 37:1059–1064. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-018-4042-1

Shen J, Wong K-T, Cheng IT et al (2017) Increased prevalence of coronary plaque in patients with psoriatic arthritis without prior diagnosis of coronary artery disease. Ann Rheum Dis 76:1237–1244. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210390

Cheng IT, Wong KT, Li EK et al (2020) Comparison of carotid artery ultrasound and Framingham risk score for discriminating coronary artery disease in patients with psoriatic arthritis. RMD Open 6:e001364. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001364

Ljung L, Sundström B, Smeds J et al (2018) Patterns of comorbidity and disease characteristics among patients with ankylosing spondylitis—a cross-sectional study. Clin Rheumatol 37:647–653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-017-3894-0

Derakhshan MH, Goodson NJ, Packham JC et al (2019) Increased risk of hypertension associated with spondyloarthritis disease duration: results from the ASAS-COMOSPA study. J Rheumatol 46:701–709. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.180538

Berg IJ, Semb AG, van der Heijde D et al (2014) Uveitis is associated with hypertension and atherosclerosis in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a cross-sectional study. Semin Arthritis Rheum 44:309–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.05.017

Klingberg E, Sveälv BG, Täng MS et al (2015) Aortic regurgitation is common in ankylosing spondylitis: time for routine echocardiography evaluation? Am J Med 128:1244-1250.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.04.032

Mageau A, Timsit J-F, Perrozziello A et al (2019) The burden of chronic kidney disease in systemic lupus erythematosus: a nationwide epidemiologic study. Autoimmun Rev 18:733–737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2019.05.011

Davidson A (2016) What is damaging the kidney in lupus nephritis? Nat Rev Rheumatol 12:143–153. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2015.159

Munguia-Realpozo P, Mendoza-Pinto C, Sierra Benito C et al (2019) Systemic lupus erythematosus and hypertension. Autoimmun Rev 18:102371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2019.102371

Chen H-A, Hsu T-C, Yang S-C et al (2019) Incidence and survival impact of pulmonary arterial hypertension among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a nationwide cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther 21:82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-019-1868-0

Chazal T, Kerneis M, Guedeney P et al (2020) Coronary artery disease in systemic lupus: a case-controlled angiographic study. Autoimmun Rev 19:102427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2019.102427

Perelas A, Arrossi AV, Highland KB (2019) Pulmonary manifestations of systemic sclerosis and mixed connective tissue disease. Clin Chest Med 40:501–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccm.2019.05.001

Khanna D, Tashkin DP, Denton CP et al (2019) Ongoing clinical trials and treatment options for patients with systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Rheumatology (Oxford) 58:567–579. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/key151

Young A, Vummidi D, Visovatti S et al (2019) Prevalence, treatment, and outcomes of coexistent pulmonary hypertension and interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol 71:1339–1349. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.40862

Jain A, Srinivas BH, Emmanuel D et al (2018) Renal involvement in primary Sjogren’s syndrome: a prospective cohort study. Rheumatol Int 38:2251–2262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-018-4118-x

Roca F, Dominique S, Schmidt J et al (2017) Interstitial lung disease in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Autoimmun Rev 16:48–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2016.09.017

Alba MA, Flores-Suárez LF, Henderson AG et al (2017) Interstital lung disease in ANCA vasculitis. Autoimmun Rev 16:722–729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2017.05.008

Moiseev S, Novikov P, Jayne D, Mukhin N (2017) End-stage renal disease in ANCA-associated vasculitis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 32:248–253. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfw046

Qi Y, Yang L, Zhang H et al (2018) The presentation and management of hypertension in a large cohort of Takayasu arteritis. Clin Rheumatol 37:2781–2788. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-017-3947-4

Jiang P, Li H, Li X (2015) Diabetes mellitus risk factors in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 33:115–121

Nicolau J, Lequerré T, Bacquet H, Vittecoq O (2017) Rheumatoid arthritis, insulin resistance, and diabetes. Joint Bone Spine 84:411–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2016.09.001

Liu Y, Hazlewood GS, Kaplan GG et al (2017) Impact of obesity on remission and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res 69:157–165. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22932

Yim KM, Armstrong AW (2017) Updates on cardiovascular comorbidities associated with psoriatic diseases: epidemiology and mechanisms. Rheumatol Int 37: 97–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-016-3487-2

Prasad M, Hermann J, Gabriel SE et al (2015) Cardiorheumatology: cardiac involvement in systemic rheumatic disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 12:168–176. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2014.206

Lee KS, Kronbichler A, Eisenhut M et al (2018) Cardiovascular involvement in systemic rheumatic diseases: an integrated view for the treating physicians. Autoimmun Rev 17:201–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2017.12.001

Ahmed S, Zimba O, Gasparyan AY (2020) Thrombosis in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) through the prism of Virchow’s triad. Clin Rheumatol 39:2529–2543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05275-1

Giacomelli R, Liakouli V, Berardicurti O et al (2017) Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: current and future treatment. Rheumatol Int 37:853–863. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-016-3636-7

Sánchez-Cano D, Ortego-Centeno N, Callejas JL et al (2018) Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: data from the spanish scleroderma study group. Rheumatol Int 38:363–374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-017-3916-x

Reiseter S, Gunnarsson R, Mogens Aaløkken T et al (2018) Progression and mortality of interstitial lung disease in mixed connective tissue disease: a long-term observational nationwide cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 57:255–262. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kex077

Lega JC, Reynaud Q, Belot A et al (2015) Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and the lung. Eur Respir Rev 24:216–238. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.00002015

Guisado-Vasco P, Silva M, Duarte-Millán MA et al (2019) Quantitative assessment of interstitial lung disease in Sjögren’s syndrome. PLoS ONE 14:e0224772. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224772

Sambataro G, Ferro F, Orlandi M et al (2020) Clinical, morphological features and prognostic factors associated with interstitial lung disease in primary Sjӧgren’s syndrome: a systematic review from the Italian Society of Rheumatology. Autoimmun Rev 19:102447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2019.102447

Raksasuk S, Ungprasert P (2020) Patients with rheumatoid arthritis have an increased risk of incident chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int Urol Nephrol 52:147–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-019-02346-4

Kapoor T, Bathon J (2018) Renal manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 44:571–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdc.2018.06.008

Bertrand D, Dehay J, Ott J et al (2017) Kidney transplantation in patients with systemic sclerosis: a nationwide multicentre study. Transpl Int 30:256–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/tri.12923

Matcham F, Rayner L, Steer S, Hotopf M (2013) The prevalence of depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 52:2136–2148. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ket169

Nerurkar L, Siebert S, McInnes IB, Cavanagh J (2019) Rheumatoid arthritis and depression: an inflammatory perspective. Lancet Psychiatry 6:164–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30255-4

Blume J, Douglas SD, Evans DL (2011) Immune suppression and immune activation in depression. Brain Behav Immun 25:221–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2010.10.008

Ambrée O, Ruland C, Scheu S et al (2018) Alterations of the innate immune system in susceptibility and resilience after social defeat stress. Front Behav Neurosci 12:141. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00141

Askim Å, Gustad LT, Paulsen J et al (2018) Anxiety and depression symptoms in a general population and future risk of bloodstream infection: the HUNT study. Psychosom Med 80:673–679. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000619

Hsu C-Y, Ko C-H, Wang J-L et al (2019) Comparing the burdens of opportunistic infections among patients with systemic rheumatic diseases: a nationally representative cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther 21:211. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-019-1997-5

Bryant PA, Baddley JW (2017) Opportunistic infections in biological therapy, risk and prevention. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 43:27–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdc.2016.09.005

Shi Y, Wu Y, Ren Y et al (2019) Infection risks of rituximab versus non-rituximab treatment for rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Rheum Dis 22:1361–1370. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185X.13596

Meroni PL, Zavaglia D, Girmenia C (2018) Vaccinations in adults with rheumatoid arthritis in an era of new disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs. Clin Exp Rheumatol 36:317–328

Furer V, Rondaan C, Heijstek M et al (2019) Incidence and prevalence of vaccine preventable infections in adult patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases (AIIRD): a systemic literature review informing the 2019 update of the EULAR recommendations for vaccination in adult patients with AIIRD. RMD Open 5:e001041. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2019-001041

Hippisley-Cox J, Young D, Coupland C et al (2020) Risk of severe COVID-19 disease with ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers: cohort study including 8.3 million people. Heart 106:1503–1511. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317393

Baral R, White M, Vassiliou VS (2020) Effect of Renin-Angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 28,872 patients. Curr Atheroscler Rep 22:61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-020-00880-6

Kitas GD, Nightingale P, Armitage J et al (2019) A multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of atorvastatin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol Hoboken NJ 71:1437–1449. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.40892

Toloza S, Urowitz MB, Gladman DD (2007) Should all patients with systemic lupus erythematosus receive cardioprotection with statins? Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol 3:536–537. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncprheum0593

Lee KCH, Sewa DW, Phua GC (2020) Potential role of statins in COVID-19. Int J Infect Dis 96:615–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.115

Zhang X-J, Qin J-J, Cheng X et al (2020) In-hospital use of statins is associated with a reduced risk of mortality among individuals with COVID-19. Cell Metab 32:176-187.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2020.06.015

Floris A, Piga M, Mangoni AA et al (2018) Protective effects of hydroxychloroquine against accelerated atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Mediators Inflamm 2018:3424136. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3424136

Miranda S, Billoir P, Damian L et al (2019) Hydroxychloroquine reverses the prothrombotic state in a mouse model of antiphospholipid syndrome: role of reduced inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. PLoS ONE 14:e0212614. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212614

Casian A, Sangle SR, D’Cruz DP (2018) New use for an old treatment: hydroxychloroquine as a potential treatment for systemic vasculitis. Autoimmun Rev 17:660–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2018.01.016

Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M et al (2020) Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in COVID-19. N Engl J Med 383:120–128. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2015432

Gendelman O, Amital H, Bragazzi NL et al (2020) Continuous hydroxychloroquine or colchicine therapy does not prevent infection with SARS-CoV-2: Insights from a large healthcare database analysis. Autoimmun Rev 19:102566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102566

Gil MR, Barouqa M, Szymanski J et al (2020) Assessment of lupus anticoagulant positivity in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Netw Open 3:e2017539–e2017539. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.17539

Mitchell F (2020) Vitamin-D and COVID-19: do deficient risk a poorer outcome? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 8:570. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30183-2

Baktash V, Hosack T, Patel N et al (2020) Vitamin D status and outcomes for hospitalised older patients with COVID-19. Postgrad Med J. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-138712

Carter SJ, Baranauskas MN, Fly AD (2020) Considerations for obesity, vitamin D, and physical activity amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Obes Silver Spring Md 28:1176–1177. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22838

Rossini M, Gatti D, Viapiana O et al (2014) Vitamin D and rheumatic diseases. Reumatismo 66:153–170. https://doi.org/10.4081/reumatismo.2014.788

Franco AS, Freitas TQ, Bernardo WM, Pereira RMR (2017) Vitamin D supplementation and disease activity in patients with immune-mediated rheumatic diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 96:e7024. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000007024

Blanch-Rubió J, Soldevila-Domenech N, Tío L et al (2020) Influence of anti-osteoporosis treatments on the incidence of COVID-19 in patients with non-inflammatory rheumatic conditions. Aging (Albany NY) 12:19923–19937. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.104117

Khoramipour K, Basereh A, Hekmatikar AA, et al (2020) Physical activity and nutrition guidelines to help with the fight against COVID-19. J Sports Sci. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2020.1807089

Cramer H, Lauche R, Langhorst J, Dobos G (2013) Yoga for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety 30:1068–1083. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22166

Shah S, Danda D, Kavadichanda C et al (2020) Autoimmune and rheumatic musculoskeletal diseases as a consequence of SARS-CoV-2 infection and its treatment. Rheumatol Int 40:1539–1554. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04639-9

Galeotti C, Bayry J (2020) Autoimmune and inflammatory diseases following COVID-19. Nat Rev Rheumatol 16:413–414. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41584-020-0448-7

Schett G, Manger B, Simon D, Caporali R (2020) COVID-19 revisiting inflammatory pathways of arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 16:465–470. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41584-020-0451-z

Saricaoglu EM, Hasanoglu I, Guner R (2020) The first reactive arthritis case associated with COVID-19. J Med Virol. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26296

Ono K, Kishimoto M, Shimasaki T et al (2020) Reactive arthritis after COVID-19 infection. RMD Open 6:e001350. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001350

Haberman RH, Castillo R, Chen A et al (2020) COVID-19 in patients with inflammatory arthritis: a prospective study on the effects of comorbidities and DMARDs on clinical outcomes. Arthritis Rheumatol Hoboken NJ. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.41456

Puntmann VO, Carerj ML, Wieters I et al (2020) Outcomes of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in patients recently recovered from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol 5:1265–1273. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3557

Huang L, Zhao P, Tang D et al (2020) Cardiac involvement in patients recovered from COVID-19 identified using magnetic resonance imaging. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 13:2330–2339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.05.004

Ojo AS, Balogun SA, Williams OT, Ojo OS (2020) Pulmonary fibrosis in COVID-19 survivors: predictive factors and risk reduction strategies. Pulm Med 2020:6175964. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/6175964

Ciurea A, Papagiannoulis E, Bürki K et al (2020) Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the disease course of patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases: results from the Swiss Clinical Quality Management cohort. Ann Rheum Dis 2020:annrheumdis-2020-218705. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218705

Jethwa H, Abraham S (2020) Should we be using the Covid-19 outbreak to prompt us to transform our rheumatology service delivery in the technology age? Rheumatology (Oxford) 59:1469–1471. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keaa218

Gasparyan AY, Misra DP, Yessirkepov M, Zimba O (2020) Perspectives of immune therapy in coronavirus disease 2019. J Korean Med Sci 35:e176. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e176

Kastritis E, Kitas GD, Vassilopoulos D et al (2020) Systemic autoimmune diseases, anti-rheumatic therapies, COVID-19 infection risk and patient outcomes. Rheumatol Int 40:1353–1360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04629-x

Venerito V, Lopalco G, Iannone F (2020) COVID-19, rheumatic diseases and immunosuppressive drugs: an appeal for medication adherence. Rheumatol Int 40:827–828. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04566-9

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation: AS, AYG, and OZ. Methodology: AS and OZ. Writing—original draft: AS and AYG. Writing—review and editing: AS, OZ, and AYG. All the authors have approved the final manuscript and take full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the contents of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, S., Gasparyan, A.Y. & Zimba, O. Comorbidities in rheumatic diseases need special consideration during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rheumatol Int 41, 243–256 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04764-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04764-5