Abstract

Taurine (a sulfur-containing β-amino acid), creatine (a metabolite of arginine, glycine and methionine), carnosine (a dipeptide; β-alanyl-l-histidine), and 4-hydroxyproline (an imino acid; also often referred to as an amino acid) were discovered in cattle, and the discovery of anserine (a methylated product of carnosine; β-alanyl-1-methyl-l-histidine) also originated with cattle. These five nutrients are highly abundant in beef, and have important physiological roles in anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory reactions, as well as neurological, muscular, retinal, immunological and cardiovascular function. Of particular note, taurine, carnosine, anserine, and creatine are absent from plants, and hydroxyproline is negligible in many plant-source foods. Consumption of 30 g dry beef can fully meet daily physiological needs of the healthy 70-kg adult human for taurine and carnosine, and can also provide large amounts of creatine, anserine and 4-hydroxyproline to improve human nutrition and health, including metabolic, retinal, immunological, muscular, cartilage, neurological, and cardiovascular health. The present review provides the public with the much-needed knowledge of nutritionally and physiologically significant amino acids, dipeptides and creatine in animal-source foods (including beef). Dietary taurine, creatine, carnosine, anserine and 4-hydroxyproline are beneficial for preventing and treating obesity, cardiovascular dysfunction, and ageing-related disorders, as well as inhibiting tumorigenesis, improving skin and bone health, ameliorating neurological abnormalities, and promoting well being in infants, children and adults. Furthermore, these nutrients may promote the immunological defense of humans against infections by bacteria, fungi, parasites, and viruses (including coronavirus) through enhancing the metabolism and functions of monocytes, macrophages, and other cells of the immune system. Red meat (including beef) is a functional food for optimizing human growth, development and health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The scientific conference entitled "Frontiers in Agricultural Sustainability: Studying the Protein Supply Chain to Improve Dietary Quality" hosted by New York Academy of Sciences highlighted growing controversies on meat consumption by humans in the U.S. (Wu et al. 2014). Over the past decades, there have been growing concerns that consumption of red meat (e.g., beef) increases risks for obesity, type II diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, colon cancer and Alzheimer's disease in humans (e.g., Nelson et al. 2016; Willett et al. 2019). Thus, beef consumption per capita in the U.S. has steadily declined from 95 lb in 1976 to only 60 lb in 2017 (USDA 2018). This has arisen, in part, from a lack of understanding of red meat as a nutritionally important source of functional amino acids (e.g., taurine and hydroxyproline), dipeptides (e.g., carnosine and anserine), and creatine (a metabolite of amino acids) with enormous physiological significance. For example, taurine is a nutritionally essential amino acid for children (particularly preterm infants) and a conditionally essential amino acid for adults (Schaffer et al. 2009). In addition, dietary supplementation with 4-hydroxyproline improves anti-oxidative function and prevents colitis in the intestine (Ji et al. 2018). Furthermore, carnosine and anserine are potent antioxidants (Hipkiss and Gaunitz 2014), whereas creatine is both an antioxidant and a major component of energy metabolism in excitable tissues (brain and skeletal muscle) (Wyss and Kaddurah-Daouk 2000). Of note, taurine, carnosine, anserine, and creatine are particularly abundant in beef skeletal muscle but are absent from plants (Wu 2013). Also, 4-hydroxyproline is abundant in meat but negligible in many plant-source foods (Hou et al. 2019). For comparison, intramuscular concentrations of balenine (β-alanyl-l-3-methylhistidine, an antioxidant and a buffering substance) are high in whale (~ 45 mmol/kg wet weight), relatively low in swine (~ 0.7 to 1 mmol/kg wet weight or 5–8% of carnosine content), and very low in cattle, chickens and sheep (~ 0.05 to 0.1 mmol/kg wet weight; Boldyrev et al. 2013; Carnegie et al. 1982; Harris and Milne 1986). This dipeptide is barely detectable in human and rat muscles (Boldyrev et al. 2013) and, therefore, is not a focus of the present article.

Growing evidence shows that taurine, carnosine, anserine, creatine and 4-hydroxyproline play crucial roles in protecting mammalian cells from oxidative stress and injury (Abplanalp et al. 2019; Avgerinos et al. 2018; Seidel et al. 2019; Wu et al. 2019). These results indicate that red meat provides not only high-quality protein for the growth of children but also functional amino acids, dipeptides and creatine for optimal human nutrition and health. However, the public is generally not aware of these beneficial nutrients in meat, including beef (e.g., Kausar et al. 2019; Uzhova and Peñalvo 2019). To provide accurate and complete information on animal-source foods, it is imperative to review pertinent articles regarding the benefits of dietary taurine, carnosine, anserine, creatine and 4-hydroxyproline on metabolic, retinal, muscle, immunological, and cardiovascular health as well as healthy ageing in humans and animal models.

Dietary sources of taurine, creatine, carnosine, anserine, and 4-hydroxyproline for humans

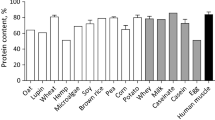

Taurine, creatine, carnosine, anserine, and 4-hydroxyproline are chemically stable and soluble in water within a physiological range of pH values. They are abundantly present in animal-source foods (such as beef). However, their reported values are highly inconsistent in the literature and may differ by 10–50 fold (Wu et al. 2016). For example, the amounts of carnosine in 100 g wet beef meat have been reported to be 14 mg (Szterk and Roszko 2014) or 1 g (Clifford 1922), and the amounts of anserine in 100 g wet beef meat to be 8.5 mg (Thornton et al. 2015) or 67 mg (Mateescu et al. 2012). Such large variations in nutrient composition may result, in part, from differences in either beef breeds or analytical techniques. To provide a much-needed database, we analyzed taurine, carnosine, anserine, creatine, and 4-hydroxyproline in cuts from three subprimals (chuck, round, and loin) of beef carcasses selected at three commercial packing plants in the United States (Table 1). These nutrients are abundant in all beef cuts (Wu et al. 2016). In contrast, taurine, carnosine, anserine, and creatine are absent from all plants [e.g., corn grains, peanuts, pistachio nuts, potatoes, soybeans, sweet potatoes, wheat flour, and white rice (Hou et al. 2019)]. Thus, vegetarians are at great risks for the deficiencies of taurine, carnosine, anserine, and creatine, particularly if they are active in physical exercise (Rogerson 2017). In addition, most of plant-source foods contained little 4-hydroxyproline and little β-alanine (a precursor of carnosine in humans) (Table 1). These data are useful for nutritionists and medical professionals to make quantitative recommendation for consumption of beef and plant-source foods by humans.

Biochemistry, physiology, and nutrition of taurine, creatine, carnosine, anserine, and 4-hydroxyproline in humans

Taurine

Tissue distribution of taurine

Taurine (2-aminoethanesulfonic acid, a slightly acidic substance) is a sulfur-containing β-amino acid. It was originally isolated from the bile salts (taurocholate, also known as cholyltaurine) of the ox by Austrian scientists F. Tiedermann and L. Gmelin in 1827. Taurine is widely distributed in the animal kingdom and to be present in relatively high concentrations in all mammalian and avian tissues, such as blood, intestine, liver, skeletal muscle, heart, brain, kidneys, and retina. A 70-kg person has ~ 70 g taurine (HuxTable 1992). Concentrations of taurine in mammalian and avian cells range from 5 to 60 mM, depending on species and cell type (Wright et al. 1986). Human skeletal muscle, heart, retina, and placenta contain 15–20, 28–40, 20–35, and 20–35 mM taurine, respectively. Because of its large mass [e.g., accounting for 45% of body weight (BW) in healthy, non-obese adults], skeletal muscle is the major site (about 70%) of taurine storage in the 70-kg adult. Taurine is abundant in the milk of mammals (e.g., 0.4 mM in human, 0.8 mM in mouse, and 2.8 mM in cats) as a physiologically essential nutrient for infants and children (Sturman 1993).

Absorption of taurine by the small intestine and transport in blood

Dietary taurine is taken up by the enterocyte across its apical membrane via Na+- and Cl−-dependent transporters, TauT, GAT2 and GAT3 (Lambert and Hansen 2011; Zhou et al. 2012), as well as PAT1 (a H+-coupled, pH-dependent but Na+- and Cl−-independent transporter), with TauT being the major transporter under physiological conditions (Anderson et al. 2009). Taurine exits the enterocyte across its basolateral membrane into the lamina propria of the intestinal mucosa via specific transporters (Fig. 1). Absorbed taurine is not degraded by the intestinal mucosa and, therefore, enters the portal circulation. Taurine is transported in blood as a free amino acid for uptake by extra-intestinal tissues (Wu 2013). Increasing dietary intake of taurine enhances its concentrations in plasma and tissues, such as skeletal muscle, brain and heart (Schaffer et al. 2009; Sirdah 2015).

Absorption of taurine, creatine, carnosine, anserine, and 4-hydroxyproline by the human small intestine and the transport of the nutrients in blood. Dietary collagen is hydrolyzed by proteases, peptidases and prolidase to free amino acids as well as 4-hydroxyproline and its peptides. Dietary taurine, creatine, carnosine, anserine, and 4-hydroxyproline are taken up by the enterocyte across its apical membrane via specific transports. Inside the cell, taurine, creatinine and anserine are not degraded, some of the 4-hydroxyproline-containing peptides are hydrolyzed to 4-hydroxyproline and its peptides, some 4-hydroxyproline is oxidized to glycine, and carnosine undergoes limited catabolism. Taurine, creatine, carnosine, anserine, and 4-hydroxyproline, as well as the products of carnosine hydrolysis (β-alanine and histidine) exit the enterocyte across its basolateral membrane into the lamina propria of the intestinal mucosa via specific transporters (Wu 2013). The absorbed nutrients are transported in blood in the free forms for uptake by extra-intestinal tissues via specific transporters. β-Ala β-alanine, CAT cationic amino acid transporter, CN1 carnosinase-1 (serum carnosinase), CN2 carnosinase-2 (tissue carnosinase), CreaT1 creatine transporter-1, CreaT2 creatine transporter-2, GAT γ-aminobutyrate transporter, HypD 4-hydroxyproline-containing dipeptides, HypT 4-hydroxyproline-containing tripeptides, OH-Pro 4-hydroxyproline, PAT1 proton-(H+-coupled) and pH-dependent but Na+- and Cl−-independent transporter for taurine (low-affinity, high-capacity transporter), PepT1 peptide transporter-1, PepT2 peptide transporter 2, PHT1/2 peptide/histidine transporters 1 and 2, TauT taurine transporters. Note that the distribution of PHT1/2 in tissues is species-specific in that human skeletal muscle expresses PHT1 but no PHT2, whereas mouse skeletal muscle expresses both PHT1 and PHT2

Synthesis of taurine in humans

Taurine is synthesized from cysteine, a product of methionine catabolism, in the liver of many mammals (Wu 2013). In humans, the rate of taurine synthesis from methionine and cysteine is exceedingly low in comparison with rats (Sturman 1993), because the activity of hepatic cysteinesulfinate decarboxylase (a key enzyme in taurine synthesis) is about three orders of magnitude lower in the young and adult men than that in rats (Sturman and Hayes 1980). Compared with livestock (e.g., cattle, pigs, and sheep) and poultry (e.g., chickens and ducks), humans also have a very low ability to synthesize taurine at any stage of life. Depending on the dietary intake of protein, nutritional status, and hepatic enzyme activity, a healthy adult may synthesize 50–125 mg taurine per day (Jacobsen and Smith 1968). Under stress or diseased conditions (e.g., heat stress, infection, obesity, diabetes, and cancer), taurine synthesis in the body may be impaired due to the suboptimal function of liver and the reduced availability of the amino acid precursors. Infants and children do not sufficiently synthesize taurine despite adequate provision of its precursors in diets (Geggel et al. 1985). In addition, individuals who consume only plant-source foods but no animal products are at increased risk for taurine deficiency, because the precursors of taurine (methionine and cysteine) are present at low concentrations in most proteins of plant origin (e.g., corn, potato, rice, wheat, and vegetables) (Hou et al. 2019).

Metabolism of taurine in humans

In animal cells, taurine undergoes limited catabolism by taurine:pyruvate transaminase or taurine:α-ketoglutarate transaminase, which catalyzes the transamination of taurine with pyruvate or α-ketoglutarate to form 2-sulfoacetaldehyde (also known as 2-oxoethanesulfonate, 2-hydroxyethanesulfonate, or isethionate) and l-alanine or l-glutamate (Read and Welty 1962). These reactions also occur in aerobic and anaerobic bacteria (Cook and Denger 2006). In addition, taurine dehydrogenase converts taurine into ammonia plus 2-sulfoacetaldehyde (an oxidation reaction) in aerobic bacteria in the presence of cytochrome C as the physiological electron acceptor (Brüggemann et al. 2004). Furthermore, taurine is oxygenated by α-ketoglutarate-dependent taurine dioxygenase to generate sulfite and 2-aminoacetaldehyde in microorganisms (including E. coli Eichhorn et al. 1997). The initial fate of the degradation of the taurine's sulfur atom is sulfite in strictly anaerobic, facultatively anaerobic, or strictly aerobic bacteria (Brüggemann et al. 2004). Thus, taurine catabolism is initiated by transamination, oxidation, or oxygenation in a species and cell-specific manner.

In humans, taurine is covalently conjugated with bile acids in the liver to form bile salts, which are then exported by the ATP-dependent bile salt export pump out of the hepatocyte and stored in the gallbladder (Hofmann 1999). During feeding, bile salts are secreted from the gallbladder via the common bile duct into the duodenum, where they facilitate the digestion and absorption of dietary lipids. The bile salts are not absorbed by the proximal small intestine (duodenum, jejunum and proximal ileum) due to the lack of their apical transporters, and are resistant to deamidation by pancreatic and mucosal enzymes (including peptidases). Instead, after the absorption of dietary lipids, bile salts enter the distal ileum, where a small fraction of them are hydrolyzed (and thus deconjugated) by microbial bile salt hydrolases to form bile acids and taurine (Foley et al. 2019). Taurine, the remaining large proportion of bile salts, and bile acids are efficiently absorbed into the enterocyte of the distal ileum by specific transporters (Figs. 1, 2). About 95% of the liver-derived bile salts and bile acids are absorbed primarily by the distal ileum into the portal circulation, and then taken up by hepatocytes of the liver (Fig. 2). This is known as the enterohepatic circulation for the ileal reabsorption of bile salts and bile acids. Only ~ 5% of the liver-derived bile salts and bile acids enter the large intestine during each enterohepatic circulation. Thus, it generally takes a prolonged period of time (e.g., months) to induce a taurine deficiency in humans and animals.

The transport of bile salts from the liver to the duodenum and the return of bile salt from the distal ileum to the liver via the enteral-hepatic circulation in humans. Conjugated bile acids are exported by the ATP-dependent bile salt export pump out of the hepatocyte through its canalicular (apical) membrane into the canaliculus. The bile salts subsequently enter bile ducts, the common hepatic duct, and the gallbladder. During digestion, the bile salts are secreted from the gallbladder to the common bile duct and then the duodenum. In the distal ileum, a fraction of bile salts is hydrolyzed by microbial bile salt hydrolases to form bile acids and taurine or glycine. Taurine, glycine and bile salts are efficiently taken up by the enterocytes of the distal ileum via specific transporters. The substances are transported in the blood for uptake by the hepatocyte via its sinusoidal basolateral membrane. During each enteral-hepatic cycle, about 95% of the liver-derived bile salts are reabsorbed to the liver. ASBT apical sodium-dependent bile salt/acid transporter (in ileal enterocytes), BA bile acids (unconjugated), BSEP bile salt export pump, CBA conjugated bile acids, Gly glycine, GlyT glycine transporters, M3 multidrug resistance protein-3, MBSL microbial bile salt hydrolases, NTCP Na+-taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide, OATP organic anion transporting polypeptide family, OSTα/β organic solute transporter subunit α/β, PD passive diffusion, Tau taurine, TauT taurine transporters

Physiological functions of taurine

It is now recognized that taurine plays major roles in human physiology and nutrition, including serving as: (1) a nutrient to conjugate bile acids to form bile salts in the liver that facilitate intestinal absorption of dietary lipids (including lipid-soluble vitamins) and eliminate cholesterol in bile via the fecal route; (2) a major antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic factor in the body; (3) a physiological stabilizer of cell membranes; (4) a regulator of modulation of Ca2+ signaling, fluid homeostasis in cells, and retinal photoreceptor activity; (5) a contributor to osmoregulation; (6) a key component of nerve and muscle conduction networks; (7) a stimulator of neurological development; and (8) an inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (CNS) (Schaffer and Kim 2018). Thus, taurine exerts beneficial effects on cardiovascular (including protection against ischemia–reperfusion injury, maintaining cell membrane structure, and reducing blood pressure), digestive, endocrine, immune, muscular, neurological, reproductive, and visual systems (Ito et al. 2014; Shimada et al. 2015; Seidel et al. 2019). For example, taurine protects cells and tissues (brain) from the toxicity of reactive oxygen species (ROS), excess metals [e.g., nickel (Xu et al. 2015) and manganese (Ahmadi et al. 2018)], and ammonia (Jamshidzadeh et al. 2017a) by maintaining the integrity of plasma and organelle (especially mitochondrion) membranes of the cell. Conversely, a deficiency of dietary taurine results in retinal degeneration in cats (Hayes et al. 1975) and children (Geggel et al. 1985) that can be corrected with taurine supplementation. Furthermore, through the production of N-chlorotaurine by activated human granulocytes and monocytes, taurine contributes to the killing of pathogenic bacteria, fungi, parasites, and viruses (Gottardi and Nagl 2010).

Health benefits of taurine supplementation

Since 1975, taurine has been used for 45 years as a dietary supplement to improve health in humans and animal models of metabolic syndrome (El Idrissi 2019; Hayes et al. 1975; Ra et al. 2019). For example, taurine supplementation can prevent diabetic rats from developing cardiomyopathy by inhibiting the expression of the angiotensin II type-2 receptor (Li et al. 2005), modulating mitochondrial oxidative metabolism (Militante et al. 2000) and electron transport activity (Jong et al. 2012), and reducing oxidative stress (Schaffer et al. 2009). In addition, oral administration of taurine can ameliorate structural abnormalities of the pancreas (Santos-Silva et al. 2015), while improving insulin production by pancreatic β-cells (Nakatsuru et al. 2018) and whole-body insulin sensitivity in subjects with hyperglycemia (Sarkar et al. 2017). This role of taurine in diabetic patients are highly significant, because they have a 25% lower concentration of taurine in plasma than normal subjects (Sak et al. 2019) and that the number of type-2 diabetic patients is increasing globally (Willet et al. 2019). Taurine supplementation may also be needed for cancer patients maintained on total parenteral nutrition, because the concentration of taurine in their plasma is 50% lower than those in healthy subjects (Gray et al. 1994). Of particular note, ingestion of 0.4–6 g taurine per day for various days improved (1) metabolic profiles in blood (including reductions in total cholesterol and low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol), and (2) cardiovascular functions in healthy subjects, as well as in patients with overweight, diabetes, hypertension, or congestive heart failure (Militante and Lombardini 2002; Xu et al. 2008). In addition, oral administration of 2 g taurine/day for 4 weeks resulted in clinically significant reductions in the frequency, duration, and intensity of muscle cramps in patients with chronic liver disease (Vidot et al. 2018). Furthermore, long-term oral administration of taurine (9 or 12 g per day) for 52 weeks can effectively reduce the recurrence of stroke-like episodes in mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS), a rare genetic disorder caused by point mutations in the mitochondrial DNA (Ohsawa et al. 2019). These beneficial effects of oral taurine are summarized in Table 2.

Waldron et al. (2018) conducted a meta-analysis to evaluate the effects of oral ingestion of taurine at various doses on endurance performance in adult humans who consumed 1–6 g taurine/day in single doses for up to 2 weeks. The authors found that the ingestion of taurine improved overall endurance performance in the subjects. This conclusion is consistent with the recent findings that taurine is a potential ergogenic aid for preventing muscle damage, attenuating muscle protein catabolism, decreasing oxidative stress, and improving performance in subjects with endurance exercise (De Carvalho et al. 2017; Page et al. 2019; Paulucio et al. 2017; Waldron et al. 2019).

Creatine

Tissue distribution of creatine

Creatine (N-[aminoiminomethyl]-N-methyl glycine), “kreas” in Greek meaning meat, was discovered by the French chemist Michel E. Chevreul in 1832 as a component of skeletal muscle in cattle. This neutral, water-soluble substance is abundant in skeletal muscle, heart, brain, and pancreas. A 70-kg adult has about 120 g of total creatine (creatine phosphate plus free creatine), with about 95% of it being in skeletal muscle (Casey and Greenhaff 2000). Total creatine is about 45% more abundant in white (fast-twitch fibers, type II) muscle than in red (slow-twitch fibers, type I) muscle (Murphy et al. 2001). In skeletal muscle and brain, creatine stores energy (primarily ATP) as creatine phosphate through the action of creatine kinase. In a resting state, about two-third and one-third of total creatine exist as creatine phosphate and creatine, respectively (McGilvery and Murray 1974). The irreversible loss of creatine as creatinine is 1.7% of the whole-body creatine (Brosnan and Brosnan 2007). This means that each day, 98.3% of creatine is continuously recycled to store ATP energy via creatine kinase. In human skeletal muscle, the concentration of creatine phosphate is about three to four times that of ATP (Gray et al. 2011; McGilvery and Murray 1974). The energy of the γ-phosphate bond (51.6 kJ/mol or 12.3 kcal/mol) in one mole of ATP is transferred to one mole of creatine for storage in vivo (Wu 2018).

Absorption of creatine by the small intestine and transport in blood

In the small intestine of mammals including humans, the apical membrane of its enterocytes absorb dietary (luminal) creatine via Na+/Cl−-coupled (i.e., sodium- and chloride-dependent) creatine transporter-1 (CreaT1) (Santacruz and Jacobs 2016). All the dietary-free creatine (100%) is absorbed by the small intestine of humans into the portal circulation (Deldicque et al. 2008). Ingested creatine phosphate, which is also abundant in meat, is hydrolyzed extracellularly by alkaline phosphatases (synthesized and released by enterocytes) into creatine and phosphate before intestinal absorption (Fernley 1971). Absorbed creatine undergoes limited phosphorylation (only 1% of ingested creatine) in the intestinal mucosa, and nearly 99% of orally ingested creatine enters the portal circulation (Jäger et al. 2011). Creatine is transported in blood as a free substance, and is rapidly taken up by extra-intestinal tissues and cells (e.g., liver, skeletal muscle, brain, kidneys, testes, and other tissues and cell types) via CreaT1, and by testes and brain also via CreaT2 (Bala et al. 2013). CreaT2 protein shares 97% homology with CreaT1. Immunohistochemical analysis has shown that CreaT1 is mainly associated with the sarcolemmal membrane in all types of skeletal muscle (Christie 2007; Murphy et al. 2001). CreaT1 is widespread in animal tissues, whereas CreaT2 is primarily present within the testes (Snow and Murphy 2001). CreaT1 is essential for normal brain and muscular function as mutations in the gene (SLC6A8) result in X-linked mental retardation, severe speech and language delay, epilepsy, autistic behavior, and muscular abnormalities (e.g., hypotonia) (Bala et al. 2013; Salomons et al. 2001). Increasing dietary intake of creatine enhances its concentrations in plasma and tissues, such as skeletal muscle, brain and heart (Derave et al. 2004; Wyss and Kaddurah-Daouk 2000). The absorption of creatine by the small intestine and its transport in the blood are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Synthesis of creatine in humans

Creatine is a metabolite of three amino acids (arginine, glycine and methionine) via the cooperation of multiple organs, primarily including the liver, pancreas and kidneys (Wu 2013). Beef is an abundant source of arginine, glycine and methionine. In contrast, all plant-source foods contain low levels of glycine and methionine, and most of plant-source foods (except for soybean, peanuts and other nuts) also have low levels of arginine (Hou et al. 2019). The pathway of creatine synthesis is initiated by arginine:glycine amidinotransferase, which transfers the guanidino group from arginine to glycine to form guanidinoacetate and ornithine. Arginine:glycine amidinotransferase is expressed primarily in the renal tubules, pancreas, and to a much lesser extent in the liver and other organs. Thus, the kidneys are the major site of guanidinoacetate formation in the body. The guanidinoacetate released by the kidneys is methylated by guanidinoacetate N-methyltransferase, which is located predominantly in the liver, pancreas, and, to a much lesser extent, in the kidneys to produce creatine (Wu and Morris 1998).

Creatine synthesis is regulated primarily through: (1) changes in expression of renal arginine: glycine amidinotransferase in both rats and humans; and (2) the availability of substrates. Dietary intake of creatine and circulating levels of growth hormone are major factors affecting de novo synthesis of creatine (Wu and Morris 1998). Activities and mRNA levels for arginine:glycine amidinotransferase in rat kidney are greatly reduced by hypophysectomy or by feeding a diet containing creatine. Neither creatine supplementation nor growth hormone influences the hepatic activity of guanidinoacetate N-methyltransferase in animals. Thus, dietary supplementation with creatine helps to spare arginine, glycine and methionine for utilization via other vital metabolic pathways, such as the syntheses of protein, nitric oxide, and glutathione (Wu 2013). This has important nutritional and physiological significance.

A 70-kg healthy adult synthesizes 1.7 g creatine per day from 2.3 g arginine, 1.0 g glycine, and 2.0 g methionine (Wu and Morris 1998), which represent 46%, 36% and 87%, respectively, of their daily dietary intakes. This amount of creatine is necessary to replace its daily irreversible loss (1.7 g/day) as creatinine from the subject through the excretion of urine. A greater loss of creatine from the body occurs in response to enhanced muscular activity (Kreider et al. 2017; Rogerson 2017), and this amount of creatine should be replenished through enhanced endogenous synthesis and dietary supplementation. For example, cycle ergometer exercise (approximately 45% of maximum O2 consumption for 90 min) increases the loss of creatine (as indicated by urinary creatinine excretion) by 52% above pre- and post-exercise values (Calles-Escandon et al. 1984).

There are new lines of evidence that endogenous synthesis of creatine is not sufficient for humans under many physiological (e.g., exercise, pregnancy and lactation) and pathological (e.g., tissue injury, ischemia, and diabetes) conditions. First, dietary creatine supplementation aids in increasing the power, strength, and mass of the skeletal muscle in athletes and bodybuilders, especially those who consume little meat (Smith et al. 2014). Second, creatine supplementation is beneficial for ameliorating sarcopenia in elderly subjects that is characterized by reductions in the mass and function of skeletal muscle (Candow et al. 2014). Third, patients with neurological and muscular disorders can respond well to creatine supplementation with improvements in health, as summarized previously. Thus, adequate provision of dietary creatine may be necessary for maintaining homeostasis and optimal health in humans (Brosnan and Brosnan 2007), particularly for vegan athletes who generally have low intake of creatine and its precursors (arginine, methionine and glycine) (Rogerson 2017).

Metabolism of creatine in humans

Creatine undergoes limited catabolism in mammalian cells (Wu 2013). However, creatine is reversibly converted by creatine kinase into creatine phosphate and is irreversibly cyclized into creatinine through spontaneous loss of one molecule of water, as indicated previously. Like creatinine, creatine phosphate is also spontaneously converted into creatinine. The breakdown of creatine phosphate results in the losses of phosphate and one molecule of water. Creatine kinase exists in the cytosolic and mitochondrial isoforms. This enzyme is not only most abundant in skeletal muscle and brain, but is also present in many tissues and cell types (Keller and Gordon 1991; Trask and Billadello 1990). When healthy adults consume 4.4 g creatine monohydrate once, plasma creatine peaks [762 µM; an 18-fold increase over the 0-min baseline value of about 40 µM (Jäger et al. 2007)] in 60 min (Kreider et al. 2017) and its half-life is 30 min (Jäger et al. 2007). Thus, creatine is rapidly cleared from plasma, and skeletal muscle is the major sink of creatine. Creatinine is excreted in urine. The amount of urinary creatinine is proportional to (and, therefore, an indicator of) skeletal muscle mass in healthy subjects.

Physiological functions of creatine

Creatine is essential for energy metabolism in the brain and skeletal muscle (Wyss and Kaddurah-Daouk 2000). In these two highly excitable tissues that can undergo rapid changes in their membrane potentials for the transport of electrical signals, creatine decreases intracellular calcium concentrations (e.g., by stimulating sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase in skeletal muscle) and extracellular glutamate concentrations (e.g., through uptake by synaptic vesicles in the brain), and prevents the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (Bender et al. 2005; Fortalezas et al. 2018). Creatine also plays an important role in anti-oxidative and anti-apoptotic reactions, scavenging free radicals, and protection against excitotoxicity in tissues (Lawler et al. 2002). For example, creatine can prevent mitochondrial disorders that are commonly associated with decreased ATP production and increased ROS production (Rodriguez et al. 2007; Wyss and Kaddurah-Daouk 2000).

Health benefits of creatine supplementation

By delaying the depletion of ATP during oxygen deprivation and reducing the availability of ROS (Balestrino et al. 1999), pretreatment with creatine can reduce the cardiac and neurological damages induced by ischemia or anoxia and that such treatment can also be useful even after the onset of stroke or myocardial infarction (Balestrino et al. 2002; Lensman et al. 2006; Osbakken et al. 1992; Perasso et al. 2013; Prass et al. 2007; Scheer et al. 2016; Shen and Goldberg 2012; Whittingham and Lipton 1981; Wilken et al. 1998; Zapara et al. 2004). Of note, creatine has been safely and beneficially administered to patients affected by age-related neurological diseases, including Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, long-term memory deficits, Alzheimer's disease, and stroke (Adhihetty and Beal 2008; Smith et al. 2014), as well as patients with pathophysiological conditions, such as gyrate atrophy, post-stroke depression, congestive heart failure, chronic musculoskeletal pain disorders, atherosclerotic diseases, and cisplatin-induced renal damage (Genc et al. 2014; Hummer et al. 2019; Persky and Brazeau 2001; Wyss and Schulze 2002). Through increasing the availability of arginine for the generation of nitric oxide (a killer of pathogenic bacteria, fungi, parasites, and viruses), dietary supplementation with creatine plays an important role in protecting humans from infectious diseases (Ren et al. 2018).

Athletes and muscle builders are major users of supplemental creatine. This is primarily because (1) both energy metabolism and production of oxidants are enhanced during exercise, and (2) creatine participates in ATP turnover in skeletal muscle and is a potent antioxidant. Due to the very low rate of creatine loss (1.7%) in the whole-body pool (creatine plus creatine phosphate), dietary supplementation with a low dose of creatine (e.g., 3 g of creatine monohydrate per day for 28 days in 76-kg men) results in a steady accumulation of creatine in skeletal muscle, and the saturation of creatine in the muscle (142 mmol/kg dry matter) occurs by day 28 (Hickner et al. 2010; Hultman et al. 1996). For comparison, the content of creatine in the skeletal muscle of adult humans without creatine supplementation is 122 mmol/kg dry matter of muscle (Hultman et al. 1996). Thus, based on the current knowledge of creatine metabolism in humans, continuous supplementation with creatine is not necessary to achieve the saturation of creatine in skeletal muscle. In the case of discontinuous supplementation of creatine, such as disruption for short intervals (e.g., 1 or 2 days per week), a longer period of supplementation (e.g., by 5–10 days) should still be sufficient to achieve the saturation of creatine in skeletal muscle. Thus, consumption of creatine monohydrate (3 g/day) over a prolonged period of time can beneficially increase the concentration of creatine in skeletal muscle to the saturation level even if the supplement is not taken every single day. When an adult consumes daily 30 g of dry beef that provides 303 mg creatine (Wu et al. 2016) as its sole dietary source, it will take about 240 days to saturate creatine in skeletal muscle.

Because of increased losses of creatine during active muscular work as noted previously, oral administration of creatine is necessary for maintaining its homeostasis in exercising subjects and this nutritional strategy is beneficial for improving their performance. For example, dietary supplementation with a low dose of creatine (as 3 g of creatine monohydrate per day) to adults can enhance the capacity of skeletal muscle to store energy by 16% [(142 – 122)/122 = 16%] (Hultman et al. 1996). The rate of utilization of creatine phosphate by the skeletal muscle of adult humans during intensive exercise is 23 mmol/L of muscle water/min (Baker et al. 2010). This is equivalent to 483 mmol/whole-body skeletal muscle/min (23 × 70 × 40% × 0.75 = 483) for a 70-kg adult with 21 L of muscle water. Through creatine recycling via creatine kinase, ingestion of 3 g of creatine monohydrate can help store 50 kcal energy in the skeletal muscle of a 70-kg person for supporting a 60-min intensive exercise (i.e., 483 mmol creatine phosphate/whole-body skeletal muscle/min × 20/142 = 68 mmol = 68 mmol × 12.3 kcal/mol × 0.001 × 60 min = 50 kcal). Thus, a small amount of supplemental creatine makes a very significant contribution to energy storage and metabolism in the skeletal muscle of humans to enhance the power and duration of muscular work. In support of this view, dietary supplementation with creatine to young adults decreases oxidative DNA damage and lipid peroxidation induced by a single bout of resistance exercise (Rahimi 2011). Oral administration of creatine phosphate (20 g/day on days 1–3 and 10 g/day for days 4–42) offers a comparable ergogenic effect to that of equal amounts of creatine monohydrate (Peeters et al. 1999).

In the International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand (Kreider et al. 2017), multiple studies have been reviewed to indicate the following. First, there is consistent evidence that oral ingestion of 3 g creatine monophosphate (equivalent to 2.64 g creatine) per day increases intramuscular creatine concentrations. This can be a biochemical basis for improvements in high-intensity exercise performance and training adaptations, as noted previously. Second, creatine supplementation may enhance post-exercise recovery, injury prevention, thermoregulation, and rehabilitation, as well as concussion, spinal cord neuroprotection. Third, creatine supplementation can improve muscular function and enhancing rehabilitation from injuries in subjects with neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., muscular dystrophy, Parkinson’s, Huntington’s disease), diabetes, osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, aging, brain and heart ischemia, adolescent depression, and pregnancy. Fourth, creatine supplementation can enhance anti-oxidative capacity and reduce oxidant-induced tissue injury. Thus, creatine is one of the most popular and beneficial nutritional ergogenic aids for athletes (Kreider et al. 2017). This conclusion continues to be supported by research findings over the past 2 years. For example, Wang et al. (2018) reported that creatine supplementation combined with exercise training for 4 weeks improved maximal muscular strength and reduced exercise-associated muscle damage in adults. Furthermore, oral consumption of creatine electrolyte improved overall and repeated short duration sprint cycling performance (Crisafulli et al. 2018), as well as anaerobic power and strength in athletes (Hummer et al. 2019).

In addition to its ergogenic effect, creatine has also been used for humans to improve cognitive function (Avgerinos et al. 2018) and reduce traumatic brain injury (Balestrino et al. 2016; Dolan et al. 2019). Furthermore, creatine supplementation ameliorates skeletal muscle dysfunction, enhances muscle functional capacity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on long-term O2 therapy (De Benedetto et al. 2018), and supports the rehabilitation of tendon overuse injury in athletes (Juhasz et al. 2018). Recently, there have been suggestions that creatine may delay or ameliorate sarcopenia in elderly subjects (Candow et al. 2019a, b), reduce fat accumulation in the liver (da Silva et al. 2017), improve muscle mass or function in cancer patients (Fairman et al. 2019), and maintain the mass and function of ageing bones (Candow et al. 2019a, b).

Growing evidence over the past 30 years shows that dietary supplementation with creatine may provide a safe and effective means in the therapeutic intervention of cancers. For example, creatine has an anti-tumor effect in vitro cell cultures and in vivo various transplanted human and rodent tumors (Kristensen et al. 1999; Lillie et al. 1993; Miller et al. 1993). In addition, Pal et al. (2016) reported that oral administration of creatine (150 mg/kg BW per day) for 10 consecutive days resulted in significant regression of tumor size in Sarcoma-180 tumor-bearing mice and improved the overall survival of the animals. Furthermore, creatine supplementation (1 g/kg BW per day for 21 days) to Walker-256 tumor-bearing rats prevented skeletal muscle atrophy by attenuating systemic inflammation and protein degradation signaling, thereby enhancing their muscle mass and survival (Cella et al. 2019). Similar beneficial effects of creatine supplementation have been obtained for humans with cancers (Fairman et al. 2019).

Carnosine

Tissue distribution of carnosine

In 1900, the Russian biochemist W. Gulewitsch discovered an abundant substance in the skeletal muscle of cattle and named this substance carnosine after “caro” or “carnis” (meaning meat in Latin), which was identified in 1918 to be a dipeptide, β-alanyl-l-histidine. Carnosine is characterized by three ionizable groups: the carboxylic group (pKa 2.77), the amino group of the β-alanine residue (pKa 9.66), and the imidazole ring in histidine (pKa 6.83), with the pKa of the whole molecule being 8.25 (Tanokura et al. 1976). Thus, at physiological pH (e.g., pH 7.0–7.4), carnosine is present in the zwitterionic form and has a net positive charge.

Concentrations of carnosine in the skeletal muscle of humans without carnosine or β-alanine supplementation range from 5 to 10 mM (Boldyrev et al. 2013), or 16.7–33.3 mmol/kg dry weight of muscle. For example, the soleus and gastrocnemius muscles of adult males contain 8 and 10 mM carnosine, respectively, or 26.7–33.3 mmol/kg dry weight of muscle (Derave et al. 2007). These values are approximately 2, 10 and 20 times greater than those in the skeletal muscle of pigs, rats and mice, respectively (Boldyrev et al. 2013). Note that bodybuilders can have carnosine concentrations as high as 15.3 mM or 51 mmol/kg dry weight, with average values being 13 mM or 43 mmol/kg dry weight (Tallon et al. 2005). The concentrations of carnosine in the olfactory bulb of the brain and the cardiac muscle are comparable to those in skeletal muscle, but those in other tissues (e.g., ~ 0.1 mM in kidneys and adipose tissue) are only 0.1% to 10% of those in skeletal muscle. Based on the report that the mean concentrations of carnosine in the skeletal muscles of women and men are 17.5 and 21.3 mmol/kg dry weight, respectively (Mannion et al. 1992), it can be estimated that a 60-kg women and a 70-kg men have 32 and 45 g carnosine, respectively. In mammals (including humans), about 99% of carnosine is present in skeletal muscle (Sale et al. 2010). Carnosine is negligible or not detectable in the plasma of humans, but is present at low concentrations (2–15 µM) in the plasma of non-primate animals.

Carnosine is more abundant in the white muscle of humans than in their red muscle (Hill et al. 2007). Based on: (1) the percentages of type I and type II fibers in skeletal muscle of adult humans, which are 88% and 12%, respectively, in soleus muscle, and 47% and 53%, respectively, in gastrocnemius muscle (Hill et al. 2007), and (2) the concentrations of carnosine in these two muscles (Derave et al. 2007), it can be calculated (0.47x + 0.53y = 10 and 0.88x + 0.12y = 8; x and y are carnosine concentration in type I and II muscles, respectively) that type I and type II muscle fibers contain 7.4 and 12.3 mM carnosine, respectively. This means that type II muscle fiber has 66% more carnosine than type I muscle fiber. Such information is important for developing an effective nutritional strategy to enhance muscular carnosine levels and improve muscular strength in athletes and elderly subjects. This is because of the following reasons. First, elite athletes can have up to 80% of type I or type II muscle fiber, depending on the type of their sports, which is a determinant of their success at competition. For example, a sprinter with 80% of white muscle fibers will have a better performance than somebody with only 30% of white muscle fibers (Komi and Karlsson 1978). Second, age-related loss of muscle mass results from a decrease in the total number of both type I and type II fibers and, but secondarily, from a preferential atrophy of type II fibers (Lexell et al. 1988; Roos et al. 1997). Therefore, adequate availability of carnosine in skeletal muscle will be beneficial for healthy ageing.

Absorption of carnosine by the small intestine and transport in blood

Dietary carnosine is absorbed by the enterocytes of the small intestine across their apical membrane via peptide transporter-1 (PepT1) (Fig. 1). This is an H+-driven process. Inside the enterocytes, a limited amount of carnosine is hydrolyzed by carnosinase-2 into β-alanine and histidine (Sadikali et al. 1975). The intracellular carnosine is exported by peptide/histidine transporters 1 and 2 (PHT1 and PHT2) out of the enterocyte across its basolateral membrane into the lamina propria of the small-intestinal mucosa. PepT1, PHT1 and PHT2 are members of the proton-coupled oligopeptide transporter family (POT-family or SLC15), and have a broad specificity for di- and tri-peptides (including carnosine and its methylated analogs). The main difference between PepT1 and PHTs is that the PHTs can transport l-histidine, in addition to di/tripeptides. Within enterocytes, a small amount of carnosine is hydrolyzed by carnosinase-2 (also known as tissue carnosinase), and nearly all of the ingested carnosine enters the portal circulation (Asatoor et al. 1970). In the blood of humans, carnosine is actively hydrolyzed by carnosinase-1 (also known as serum carnosinase; an enzyme that is synthesized and released from the liver) into β-alanine and histidine, which are then taken up by extra-intestinal cells via specific transporters for beta-amino acids and basic amino acids, respectively. Carnosine in plasma, if any, is transported into extra-intestinal tissues and cells via PepT2 (peptide transporter 2) as well as PHT1 and PHT2. PepT2, which has a broad specificity for di- and tri-peptides as does PepT1, is more widespread than PepT1 in extra-intestinal tissues and cells. Increasing dietary intake of carnosine enhances its concentrations in skeletal muscle, brain and heart (Boldyrev et al. 2013).

Ingestion of 4 g synthetic carnosine alone by adult humans does not affect its concentrations in plasma due to high carnosinase-1 activity in plasma that rapidly hydrolyzes carnosine into β-alanine and histidine, but does increase the urinary output of carnosine (Gardner et al. 1991). Urinary carnosine accounts for 14% of the ingested amount over a 5-h period and peaks at 2 h after the consumption of carnosine. Similarly, within 90 min after the ingestion of 4.5 g carnosine by adult humans, the concentration of carnosine in serum does not change but the concentrations of histidine and β-alanine rapidly increase (Asatoor et al. 1970). This is consistent with the high activity of carnosinase-1 in the plasma of humans to hydrolyze carnosine. Interestingly, consumption of beef by men and women can result in an increase in the concentration of carnosine in their plasma that peaks (145 µM) at 2.5 h after intake and returns to the baseline value at 5.5 h after intake (Park et al. 2005). It is possible that some components in beef [anserine, amino acids (e.g., histidine and β-alanine), and copper] inhibit serum carnosinase (Bellia et al. 2014; Boldyrev et al. 2013), so that the circulating levels of carnosine are substantially elevated. This can directly supply the dipeptide to extra-intestinal tissues (e.g., heart and pancreas) and cells (e.g., red blood cells and immunocytes). In this regard, ingestion of beef as a whole food may be superior to oral administration of synthetic carnosine alone for humans.

Synthesis of carnosine in humans

Synthesis of carnosine from β-alanine and histidine is catalyzed by ATP-dependent carnosine synthetase (a cytosolic enzyme) (Wu 2013), which is primarily present in skeletal muscle, heart, and certain brain regions (e.g., the olfactory bulb) (Drozak et al. 2010; Harding and O'Fallon 1979). The sources of β-alanine are diets and endogenous syntheses from the catabolism of aspartate (mainly in bacteria), malonic acid semialdehyde (transamination with glutamate), coenzyme A, pyrimidines, polyamines (Wu 2013). The sources of histidine are diets and the degradation of hemoglobin (which is very rich in histidine), actin, myosin, and other proteins in the body.

Based on the kd (fractional turnover rate) value of 0.0133/day for the loss of intramuscular carnosine at the physiological steady state (Spelnikov and Harris 2019), the intramuscular concentrations of carnosine in women and men (17.5 and 21.3 mmol/kg dry weight, respectively), skeletal muscle mass (45% of BW), and its dry matter content (30%), it can be estimated that a 60-kg woman and a 70-kg man synthesizes 427 and 606 mg carnosine per day, respectively. The KM values of this enzyme for β-alanine and histidine are 1.0–2.3 mM (Ng and Marshall 1978) and 16.8 µM (Horinishi et al. 1978), respectively. The value of carnosine synthetase for β-alanine is much greater than or comparable to the intracellular concentration of β-alanine in the brain (0.09 mM) or skeletal muscle (1.0 mM), respectively (Wu 2013). In contrast, the value of carnosine synthetase for histidine is much lower than the intracellular concentration of histidine in the brain (143 µM) and skeletal muscle (404 µM), respectively (Wu 2013). As reported for nitric oxide synthase whose KM value for arginine is much greater in cells than that in assay tubes (Wu and Meininger 2000), it is possible that the KM of carnosine synthetase for histidine in vivo is much greater than that (i.e., 16.8 µM) reported for the purified enzyme under in vitro assay conditions, due to complex protein–protein and enzyme–substrate interactions in vivo.

Availability of β-alanine primarily limits carnosine synthesis by carnosine synthetase in human skeletal muscle and the olfactory bulb, but adequate provision of histidine in diets is also critical for maximal production of carnosine because histidine is not synthesized de novo (Hill et al. 2007; Sale et al. 2010). For example, supplementation with β-alanine to humans (e.g., 2–6 g/day) dose-dependently increases the concentrations of carnosine in skeletal muscle by 20–80%, but dietary supplementation with 3.5 g histidine/day for 23 days has no effect on intramuscular carnosine concentrations in non-vegetarian adults (Blancquaert et al. 2017; Culbertson et al. 2010). Furthermore, dietary supplementation with 3.2 or 6.4 g β-alanine per day (as multiple doses of 400 or 800 mg) or with l-carnosine (isomolar to 6.4 g β-alanine) per day for 4 weeks augmented intramuscular carnosine concentrations by 42%, 64% and 66% (Harris et al. 2006). These results reveal that histidine is not a limiting factor in carnosine synthesis in adults consuming adequate histidine from animal-source foods. Thus, in non-vegetarian humans, consumption of an equal amount of β-alanine and carnosine effectively increases intramuscular carnosine concentrations to the same extent. It is unknown whether dietary intake of histidine limits carnosine synthesis in vegetarians with or without β-alanine supplementation.

It is noteworthy that dietary supplementation with β-alanine (6 g/day for 23 days) to adults reduces the concentrations of histidine in their plasma and skeletal muscle by 31% and 32%, respectively, possibly due to reduced intestinal absorption of histidine and increased utilization of histidine for carnosine synthesis by skeletal muscle (Blancquaert et al. 2017). Whether this reduction in histidine with β-alanine supplementation has a long-term adverse effect on human health is unknown, but it is prudent to ensure that dietary intake of histidine via supplementation or consumption of histidine-rich foods (e.g., meat) is sufficient. In contrast, oral administration of carnosine increases the concentration of not only β-alanine but also histidine in the plasma of humans (Asatoor et al. 1970), indicating an advantage of the consumption of synthetic carnosine or carnosine-rich foods (e.g., beef) over the consumption of β-alanine alone.

Within a mammalian species, the synthesis of carnosine is affected by multiple factors, including age, sex, muscle fiver type, muscular activity, and diet (Harris et al. 2012). For example, in a study with 9- to 83-year-old humans, Baguet et al. (2012) found that the concentration of carnosine in skeletal muscle increased between 9 and 18 years of age but decreased thereafter with advanced ages. Likewise, the content of carnosine in soleus muscle declines with age between 17- and 47-year-old subjects (Everaert et al. 2011). In adult humans, white muscle fibers contain 30–100% more carnosine than red muscle fibers, and men have 22–82% greater concentrations of carnosine in skeletal muscle than women (Everaert et al. 2011; Mannion et al. 1992). For example, compared to age-matched women, men have 36, 28 and 82% greater concentrations of carnosine in soleus, gastrocnemius and tibialis anterior muscles, respectively (Everaert et al. 2011). It is possible that androgens enhance carnosine synthesis in skeletal muscle, but the circulating levels of testosterone in healthy adult men do not appear to be related to their intramuscular carnosine concentrations (Everaert et al. 2011). Finally, long-term exercise (e.g., 2 days per week for 8 weeks for sprinters) increases intramuscular carnosine levels in male subjects by 113%, which is associated with a 9% increase in the mean power (e.g., during 30-s maximal cycle ergometer sprinting) was significantly increased following training (Suzuki et al. 2004); similar results (a 100% increase in intramuscular carnosine levels) were obtained for resistance-trained bodybuilders (Tallon et al. 2005). Finally, because plant-source foods contain much lower concentrations of β-alanine and histidine (Hou et al. 2019) than animal products (Wu et al. 2016) and because the formation of β-alanine in vegans is limited (Harris et al. 2012), the synthesis of carnosine in vegans is inadequate and its concentrations in soleus and gastrocnemius muscles are 17% and 26%, respectively, lower than those in omnivores who consume some meat that is an excellent source of both β-alanine and histidine (Everaert et al. 2011; Harris et al. 2012).

Metabolism of carnosine in humans

Carnosine is hydrolyzed by carnosinase-2 (a Zn2+-dependent cytosolic enzyme in tissues) and carnosinase-1 (a Mn2+-dependent extracellular enzyme in human blood), but not by proteases or dipeptidases, in humans and animals. Expression of these two isoforms of carnosinase occurs in a tissue-specific manner. Specifically, carnosinase-1 is expressed in the liver, brain, and kidneys but is absent from skeletal muscle and the small intestine (Boldyrev et al. 2013; Everaert et al. 2013). Expression of carnosinase-2 in tissues other than the liver, brain, and kidneys is limited shortly after birth and gradually increases to adult levels during adolescence. Accordingly, the plasma concentrations of carnosine are 5–10 µM in preterm infants, 3–5 µM in term infants, and absent in healthy adults (Asatoor et al. 1970; Valman et al. 1971). In humans, carnosinase-1 that is present in serum at a very high activity is synthesized and secreted mainly by the liver. In contrast, the serum of healthy non-primate mammals (except for the Syrian golden hamster) and birds contains no carnosinase (Boldyrev et al. 2013). Thus, carnosine is stable in the plasma of rats and farm animals but not humans (Yeum et al. 2010). The concentrations of carnosine are 2–15 µM in the plasma of non-primate land animals. In contrast, carnosinase-2 is more widely expressed in mammalian tissues (including skeletal muscle and the small-intestine mucosa of some species), but is absent from the serum or cerebrospinal fluid of mammals or birds (Bellia et al. 2014; Boldyrev et al. 2013; Everaert et al. 2013). The gastric and colonic mucosae of mammals (including humans, pigs, cattle and rats) contain no carnosinase-1 or carnosinase-2 activity.

As noted previously, in humans, dietary carnosine is absorbed intact by the small intestine into the portal circulation, but is rapidly hydrolyzed by serum carnosinase in plasma into β-alanine and histidine; both of the amino acids are reused for carnosine synthesis by skeletal muscle, heart, and the olfactory bulb of the brain (Boldyrev et al. 2013; Harris et al. 2006). In the human skeletal muscle (pH 7.1), which lacks carnosinase-1, the degradation of carnosine by carnosinase-2 is very limited, because its optimal pH 9.5 is much greater than the intracellular pH and its Vmax is 30 times lower than that of carnosinase activity in the human kidneys (Lenney et al. 1985). This explains the relatively high concentration of carnosine in mammalian skeletal muscle. The mean half-life of intramuscular carnosine in adult humans has been estimated to be 52 days (a range of 46–60 days; Spelnikov and Harris 2019). This indicates that carnosine has a relatively high degree of biological stability in the body. Consistent with this view, the turnover rate of carnosine in adult humans at the physiological steady state is 1.33%/day (Spelnikov and Harris 2019). Excess carnosine, β-alanine and histidine are excreted from the body via the urine (Sale et al. 2010). The healthy adult without ingesting carnosine excreted 24 µmol carnosine in 5 h (Gardner et al. 1991). In adult humans consuming 150 g beef or chicken broth, urinary concentrations of carnosine within 7 h after intake were 13- and 15-fold greater, respectively, than the values for no consumption of the meat (Yeum et al. 2010).

Physiological functions of carnosine

Carnosine has a functional imidazole ring, which can readily donate hydrogen to free radicals for their conversion into non-radical substances (Kohen et al. 1988). Such an ability of the imidazole ring is enhanced by the β-alanine moiety in carnosine. The major physiological functions of carnosine include: pH-buffering, activation of muscle ATPase to provide energy, metal-ion (copper, zinc and iron) chelation and homeostasis, antioxidant capacity (directly through scavenging ROS and peroxyl radicals and indirectly through chelating metals), and protection against lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation, and the formation of advanced protein glycation (by inhibiting protein carbonylation and glycoxidation) and lipoxidation end products (by suppressing lipid peroxidation) (Barca et al. 2019; Boldyrev et al. 2013; Nelson et al. 2019). The pKa value of the imidazole ring of carnosine (6.83) is closer to the intracellular pH in cells than the imidazole ring of free l-histidine (6.04) (Wu 2013). As a positively charged molecule, carnosine can neutralize ATP (~ 5 mM, a negatively charged molecule). Thus, in skeletal muscle, carnosine (5–10 mM) would be a better buffering molecule than free histidine (0.4 mM). Davey (1960) reported that carnosine, together with anserine, accounted for approximately 40% of the pH-buffering capability in the skeletal muscles of rabbits and pigeons. Likewise, Sewell et al. (1992) found that carnosine contributed about 20% of the buffering in type I muscle fibers and up to 46% in type IIb fibers, and these results are consistent with the findings that type I muscle fibers have a lower glycolysis activity and accumulate less lactic acid than type IIb muscle fibers. A similar buffering function of carnosine also applies to the olfactory bulb of the brain, which has only 0.14 mM histidine (Wu 2013). The β-alanine moiety of carnosine contributes to a reduction in its oxidation potential, and carnosine is oxidized at a lower oxidation potential than histidine to remove oxidants (Kohen et al. 1988). Thus, carnosine readily forms a charge-transfer complex with oxygen free radicals (e.g., superoxide radical, hydroxyl radicals, peroxyl radicals, and nitric oxide), non-radical ROS (e.g., peroxynitrite, hypochlorous acid, singlet oxygen, and H2O2), and deleterious aldehydes (e.g., malondialdehyde and formaldehyde) to confer anti-oxidative effect and protect cell membrane and intracellular organelles (e.g., mitochondria) from damage (Kohen et al. 1988; Pavlov et al. 1993). Besides the anti-ischemic effect of carnosine on the brain and heart, there is evidence that carnosine can maintain the integrity of the DNA molecule, as indicated by studies with telomere (Shao et al. 2004). The latter is a region of repetitive nucleotide sequences at each end of a chromosome, which protects the end of the chromosome from deterioration or from fusion with neighboring chromosomes. Specifically, carnosine can reduce telomere shortening rate possibly by protecting telomeres from damage, thereby contributing to the life-extension effect of carnosine (Shao et al. 2004). Thus, carnosine is beneficial for healthy ageing.

Other physiological functions of carnosine include the regulation of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-release channels and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ homeostasis in skeletal muscle, activation of its phosphorylase activity to promote glycogen breakdown (Johnson et al. 1982), inhibition of the angiotensin converting enzyme, enhancement of nitric oxide availability in endothelial cells, potentiation of cardiac and skeletal muscle contractilities, serving as a neurotransmitter or a neuromodulator, as well as the modulation of excitation–contraction coupling in skeletal muscle and the activity of the sympathetic nerve innervating the muscle (Nagai et al. 2019; Berezhnoy et al. 2019). Carnosine also plays a role in the inhibition of the growth and migration but induction of apoptosis of tumor cells, including human glioblastoma cells as well as colorectal and ovarian carcinoma cells (Hipkiss and Gaunitz 2014; Hsieh et al. 2019; Iovine et al. 2016), as well as the suppression of the release of interleukin-6 by lipopolysaccharides plus interferon-γ-activated macrophages (Caruso et al. 2017). Most recently, carnosine was reported to influence epigenetic regulation of gene expression in mammalian cells via increased histone acetylation (Oppermann et al. 2019). Compared with its constituent amino acids, the formation of carnosine can reduce intracellular osmolarity in the skeletal muscle and olfactory bulb, thereby protecting their integrity and function. In addition, being a positively charged dipeptide that is resistant to peptidases, carnosine does not readily exit cells and can be accumulated inside the cells at high concentrations within physiological ranges. Through its intracellular actions, carnosine confers a vasorelaxing effect to reduce blood pressure (Ririe et al. 2000), stroke, and seizures (Horning et al. 2000), and carnosine is particularly beneficial for ameliorating ageing-related disorders such as cataract and neurological diseases (Cararo et al. 2015; Schön et al. 2019). Thus, carnosine plays an important role in maintaining cell structure and function, as well as whole-body homeostasis and healthy aging, while reducing the risk of oxidative stress-related diseases, such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, atherosclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, stroke and seizures.

Health benefits of carnosine supplementation

Much research has demonstrated the beneficial effects of dietary supplementation with carnosine on animal models of human diseases (Derave et al. 2019). These effects include decreased plasma glucose and amelioration of diabetic complications (e.g., nephropathy, ocular damage, and retinopathy) in diabetic mice (Lee et al. 2005; Pfister et al. 2011); reduced lipid oxidation and augmented anti-oxidative capacities [e.g., restoring of blood glutathione and basal activities of antioxidant enzymes in aging rats (Aydin et al. 2010a,b; Hipkiss and Brownson 2000)] and in pigs (Ma et al. 2010); amelioration of acetaminophen-induced liver injury (Yan et al. 2009), thioacetamide- or hyperammonemia-induced liver cirrhosis (Aydin et al. 2010a,b; Jamshidzadeh et al. 2017b), and ethanol-induced chronic liver injury in rats (Liu et al. 2008). Dietary supplementation with carnosine also results in decreases in malondialdehyde, oxidative stress (including ischemic oxidative stress and cerebral ischemia), and ethanol-induced protein carbonyls in brains (Berezhnoy et al. 2019; Fedorova et al. 2018); amelioration of neurological disorders, including autism spectrum disorder in children (Chez et al. 2002; Kawahara et al. 2018); protection against cardiovascular injury (Abplanalp et al. 2019; Artioli et al. 2019) and bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis in rats (Cuzzocrea et al. 2007); cardiomyopathy in rats induced by chemotherapeutic agents that cause hydroxyl radical formation and lipid peroxidation (Dursun et al. 2011); ROS-induced renal damage in mice (Fouad et al. 2008); and promotion of wound healing in rodents (Ansurudeen et al. 2012). Through augmenting respiratory burst in neutrophils and their production of ROS, as well as modulating the release of the virulent influenza virus from activated neutrophils, oral administration of carnosine and anserine reduces virus dissemination in humans (Babizhayev and Deyev 2012; Babizhayev et al. 2014).

Extensive animal experiments have laid a strong foundation for human clinical studies, which indicate beneficial effects of supplementation with carnosine (0.5–2 g/day) for 1–6 months on subjects with chronic diseases (Table 2). For example, oral administration of carnosine has been used to ameliorate syndromes in patients with gastric ulcers (Sakae and Yanagisawa 2014), Parkinson disease (Boldyrev et al. 2008), schizophrenia (Chengappa et al. 2012), autistic spectrum disorder (Chez et al. 2002), and ocular diseases (Babizhayev et al. 2001). Carnosine supplementation has also been shown to attenuate elevated levels of glucose, triglycerides, advanced glycation end products, and tumor necrosis factor-α levels in patients with type-2 diabetes (Houjeghani et al. 2018) and in overweight or obese pre-diabetic subjects (de Courten et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2015), enhance cardiac output and improve the quality of life in patients with heart failure (Cicero and Colletti 2017), as well as renal functional integrity and anti-oxidative capacity in pediatric patients with diabetic nephropathy (Elbarbary et al. 2017); ameliorate insulin resistance (Baye et al. 2019), and increase lean-tissue mass in obese or overweight subjects (Liu et al. 2015).

Exercise is associated with increases in Ca2+ influx into the myofibers of skeletal muscle (regulating myosin-actin cross bridging and action potential along the muscle fiber membrane) and in the production of ROS and H+ by skeletal muscle. Excessive ROS and H+ must be removed rapidly, for example, by carnosine to sustain muscular activity and ATP generation. Therefore, dietary supplementation with β-alanine or carnosine improves muscular performance in humans (Matthews et al. 2019). This notion is further substantiated by several lines of evidence. First, increases in carnosine concentrations in soleus (+ 45%) and gastrocnemius (+ 28%) through oral administration of β-alanine (5 g/day) for 7 weeks enhanced rowing performance in athletes (Baguet et al. 2010). Similarly, supplementation with 4–6.4 g β-alanine per day (8 dosing of 0.4 or 0.8 g for each dosing) for 10 weeks to non-vegetarian men (consuming 0.25–0.75 g β-alanine from histidine dipeptides in meat) augmented intramuscular carnosine concentrations by 74% (93% and 57% increase in type I and II muscle fibers, respectively) and improved their high-intensity cycling performance (Hill et al. 2007). Second, dietary supplementation with 2.5 g of a mix of anserine and carnosine (2:1) per day for 13 weeks enhanced cognitive functioning and physical capacity (indicated by the Senior Fitness Test) in the elderly (Szcześniak et al. 2014). Third, oral administration of carnosine (500 mg once daily) for 6 months improved exercise performance (indicated by the 6-min walking test, peak O2 consumption, and peak exercise workload), as well as the quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure (Lombardi et al. 2015).

Anserine

Tissue distribution of anserine

After the discovery of carnosine in beef, scientists analyzed this substance in other animal species. In 1929, N. Tolkatschevskaya and D. Ackermann independently identified a carnosine-like compound in goose skeletal muscle to be a dipeptide (methyl carnosine; β-alanyl-1-methyl-l-histidine), which was named anserine after the taxonomic name for the goose. This peptide is characterized by three ionizable groups: the carboxylic group (pKa 2.64), the amino group of the β-alanine residue (pKa 9.49), and the imidazole ring in histidine (pKa 7.04), with the pKa of the whole molecule being 8.27 (Bertinaria et al. 2011). Thus, at physiological pH (e.g., pH 7.0 to 7.4), anserine is present in the zwitterionic form and has a net positive charge.

Anserine is abundant in the skeletal muscles of birds, certain fish [e.g., salmon, tuna and trout (Boldyrev et al. 2013)], and beef (Wu et al. 2016), but is absent from human tissues (including skeletal muscle, heart and brain) (Mannion et al. 1992). Among the animal kingdom, anserine is the major histidine-containing dipeptide in the skeletal muscles of dog, cat, lion, rabbit, agouti, mouse, kangaroo, wallaby, opossum, cod, smelt, marlin, whiting, croaker, tuna, Japanese char, salmon and trout (Boldyrev et al. 2013). Intramuscular concentrations of anserine in these non-primate species range from 2 mM for opossum to 21 mM for marlin. High concentrations of anserine in the mM range are also present in the brains of the non-primate animals. In contrast, anserine is usually absent from the plasma of healthy adult humans without anserine intake (Everaert et al. 2019) and is present at 2–10 µM in the plasma of non-primate animals depending on species (Boldyrev et al. 2013).

Intramuscular and cardiac concentrations of anserine are affected by a number of factors, including muscle fiber type, muscular contractility, and health status. For example, white muscle fibers contain much more anserine than red muscle fibers, as the concentrations of anserine and carnosine were 2.2- and 2.8-fold higher, respectively, in breast versus thigh muscle (Barbaresi et al. 2019). In rat skeletal muscles (longissimus dorsi and quadriceps femoris), the concentrations of carnosine and anserine decrease by 35–50% during senescence, and are 35–45% lower in hypertensive animals than in normotensive ones (Johnson and Hammer 1992). Similarly, in rat cardiac muscle, the concentrations of total histidine dipeptides decline by 22% during senescence and, are 35% lower in hypertensive animals than in normotensive ones (Johnson and Hammer 1992).

Absorption of anserine by the small intestine and transport in blood

In humans, dietary anserine is absorbed by the small intestine, transported in blood, and taken up by extra-intestinal tissues as described previously for dietary carnosine (Fig. 1), except that the rates of catabolism of anserine to β-alanine and 1-methyl-histidine by serum carnosinase (carnosinase-1) in plasma and by carnosinae-2 in non-blood tissues are lower than those for carnosine (Yeum et al. 2010). A study with adult humans has shown that oral administration of 2 g anserine/60 kg BW without or with 19.4 g food increased the concentration of anserine in plasma, which peaked (52 and 40 µM, respectively) at 45 min after consumption and returned to the baseline value at 3 h after consumption (Kubomura et al. 2009). In the absence of food intake, the oral administration of anserine increased the concentration of 1-methyl-histidine in the human plasma, which peaked (125 µM) at 60 min and declined thereafter to ~ 100 µM at 4 h after consumption. When anserine was consumed along with 19.4 g food, because the intestinal absorption of anserine was delayed, the oral administration of anserine increased the concentration of 1-methyl-histidine in the human plasma to the peak value of ~ 100 µM) at 75 min, which remained essentially unchanged at 4 h after consumption. Similar results were obtained for β-alanine (Yeum et al. 2010). In adult humans, the T1/2 of orally administered anserine in plasma is 1.28 or 1.35 h, respectively, without or with food consumption (Kubomura et al. 2009). Thus, in humans, the circulating anserine is cleared rapidly as is carnosine. Increasing dietary intake of anserine enhances its concentrations in skeletal muscle, brain and heart (Boldyrev et al. 2013).

Synthesis of anserine in non-primate animals

Humans and other primates do not synthesize anserine. However, non-primate animals can synthesize anserine from β-alanine and histidine at various rates, depending on species (Boldyrev et al. 2013). The ATP-dependent pathways require anserine synthetase, as well as carnosine synthetase plus carnosine 1-methyltransferase (Wu 2018). The anserine synthetase pathway is a minor one, because 1-methylhistidine is limited in animal tissues. The carnosine N-methyltransferase is quantitatively important and physiologically active for anserine synthesis in skeletal muscle. Because carnosine 1-methyltransferase and guanidinoacetate methyltransferase (the enzyme that converts guanidinoacetate into creatine) compete for S-adenosylmethionine (Wu 2013), there may be a close metabolic relationship between anserine and creatine syntheses in non-primate animals. Like carnosine, the homeostasis of anserine in skeletal muscle is controlled by the availability of β-alanine or its degradation via transamination (Blancquaert et al. 2017).

Metabolism of anserine in humans

Besides using carnosine as a substrate, carnosinase also acts on anserine, but its enzymatic activity is lower for anserine than for carnosine (Boldyrev et al. 2013; Yeum et al. 2010). Thus, anserine is metabolized in humans and other animals as described previously for carnosine, except that serum carnosinase degrades anserine at a lower rate than carnosine and, therefore, oral administration of anserine or anserine-containing food (e.g., beef) can transiently increase the concentration of anserine in the human plasma (Everaert et al. 2019; Yeum et al. et al. 2010). Excess anserine, β-alanine and 1-methyl-histidine are excreted from the body via the urine (Sale et al. 2010). Oral administration of 4, 10 and 20 mg anserine/kg BW to young adults dose-dependently increased its urinary excretion, with peak concentrations of anserine in urine at 90 min after intake (Everaert et al. 2019). Even in subjects consuming 20 mg anserine/kg BW, the peak concentration of anserine in the plasma was only 3 µM, indicating extensive catabolism of this peptide by serum carnosinase. In adult humans consuming 150 g beef or chicken broth, urinary concentrations of anserine within 7 h after intake were 14- and 243-fold greater, respectively, than the values for no consumption of the meat (Yeum et al. 2010).

Physiological functions of anserine

Anserine has physiological functions similar to those of carnosine, including H+ buffering, antioxidation, modulation of muscle contractility (e.g., excitation and contraction through transmembrane potential maintenance and electromechanical coupling), and regulation of metabolism (Boldyrev et al. 2013; Everaert et al. 2019; Kohen et al. 1988). However, as a methylated metabolite of carnosine, anserine has some biochemical properties that are different from those of carnosine. For example, in contrast to carnosine, anserine does not chelate copper and may not regulate nitric oxide availability in cells (Boldyrev et al. 2013). Also, although anserine and carnosine exhibit an equal anti-oxidative activity (Boldyrev et al. 1988), anserine (1 mM), but not carnosine (1 mM), increased the protein and mRNA levels of heat shock protein-70 in renal tubular cells treated with 25 mM glucose or 20–100 µM hydrogen peroxide (Peters et al. 2018). Furthermore, anserine, but not carnosine, inhibits carnosinase activity (Derave et al. 2019). Thus, anserine may potentiate the action of carnosine in the body.

Health benefits of anserine supplementation

Some studies have shown the beneficial effects of dietary supplementation with anserine on animal models of human diseases characterized by oxidative stress. For example, intraperitoneal administration of 0.1 or 1 mg anserine to hyperglycemic rats (250–300 g of body weight) reduced hyperglycemia and plasma glucagon concentrations by suppressing sympathetic nerve activity (Kubomura et al. 2010). Similarly, intravenous administration of anserine every 2 days for 6 days to 12-week-old diabetic db/db mice reduced blood glucose concentration by 20%, vascular permeability by one-third, and urinary proteinuria by 50% (Peters et al. 2018). In addition, Kaneko et al. (2017) reported that oral administration of anserine (10 mg/mouse) to 18-month-old AβPPswe/PSEN1dE9 mice (a model of Alzheimer's disease) for 8 weeks completely recovered the memory deficits, improved pericyte coverage on endothelial cells in the brain, and suppressed glial inflammatory reactions. These results indicate that anserine ameliorates neurovascular dysfunction and improves spatial memory in aged animals. Interestingly, the effects of anserine on the renal function seem to be dependent on its doses via actions on the histaminergic nerve. For example, intravenous administration of 1 µg anserine to urethane-anesthetized rats suppressed the renal sympathetic nerve activity, blood pressure, and heart rate, whereas intravenous administration of 1 mg anserine had the opposite effects (Tanida et al. 2010). Thus, because of its anti-oxidative and vasodilatory actions, dietary supplementation with anserine-rich chicken meat extracts ameliorated carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatic oxidative stress and injury in rats (Peng and Lin 2004), while improving glucose homeostasis and preventing the development of hypertension in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats (Matsumura et al. 2002).