Abstract

This study investigated the effects of acute oral taurine ingestion on: (1) the power–time relationship using the 3-min all-out test (3MAOT); (2) time to exhaustion (TTE) 5% > critical power (CP) and (3) the estimated time to complete (Tlim) a range of fixed target intensities. Twelve males completed a baseline 3MAOT test on a cycle ergometer. Following this, a double-blind, randomised cross-over design was followed, where participants were allocated to one of four conditions, separated by 72 h: TTE + taurine; TTE + placebo; 3MAOT + taurine; 3MAOT + placebo. Taurine was provided at 50 mg kg−1, whilst the placebo was 3 mg kg−1 maltodextrin. CP was higher (P < 0.05) in taurine (212 ± 36 W) than baseline (197 ± 40 W) and placebo (193 ± 35 W). Work end power was not affected by supplement (P > 0.05), yet TTE 5% > CP increased (P < 0.05) by 1.7 min after taurine (17.7 min) compared to placebo (16.0 min) and there were higher (P < 0.001) estimated Tlim across all work targets. Acute supplementation of 50 mg kg−1 of taurine improved CP and estimated performance at a range of severe work intensities. Oral taurine can be taken prior to exercise to enhance endurance performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The critical power (CP) demarcates the boundary between heavy and severe exercise domains (Jones et al. 2010). It represents the highest power output that can be maintained, without a continuous rise in oxygen uptake (\( \dot{V}{\text{O}}_{2} \)) and blood lactate or reductions in intra-muscular phosphocreatine stores (Jones et al. 2008, 2010; Vanhatalo et al. 2016). Whilst the CP is typically measured over several days and bouts of constant load exercise, it has been shown that the finite work capacity above CP (W′) can be completely utilised in a single all-out, 3-min exercise test (3MAOT). This test permits reliable and valid calculation of an equivalent CP and a W′ value—the work end power (WEP) (Vanhatalo et al. 2007; Dekerle et al. 2006). Therefore, this single-visit test permits quantification of work done above and below the CP; hence, the two-component model (Vanhatalo et al. 2007). Parameters of the power–time relationship can be used to describe a ‘gold standard’ demarcation of the metabolic steady state (CP; Jones et al. 2019) and the finite capacity of individuals > CP (W′), which can be used in combination to determine exercise performance (Jones et al. 2010; Jones and Vanhatalo 2017).

The CP provides a boundary that relates to both metabolic and respiratory control processes in the exercising human (Poole et al. 1988) and can be used to assess responses to training or acute dietary interventions, including caffeine (Machado et al. 2010; Cheng et al. 2016; Silveira et al. 2018), creatine (Smith et al. 1998; Miura et al. 1999; Vanhatalo and Jones 2009) and dietary nitrates (Kelly et al. 2013). Taurine, a sulphur-containing amino acid, is the most abundant free amino acid in mammalian tissue (Huxtable 1992), and is available to facilitate a variety of biological processes that can support exercise performance. As reported with the above-mentioned acute dietary supplements, taurine supplementation could theoretically alter components of the power–time relationship. For example, aerobically biased (endurance) exercise has typically been improved following taurine supplementation (see Waldron et al. 2018a; Souza et al. 2017 for reviews) and effects on skeletal muscle function have been reported (Dutka et al. 2014; Lim et al. 2018), which might collectively explain the improved exercise efficiency following oral administration (Paulucio et al. 2017). These mechanistic actions relate to the factors ascribed to govern the balance of CP and W′, which include a loss of muscle efficiency, characterised by distinct metabolic (Jones et al. 2008; Vanhatalo et al. 2016) and neuromuscular (Burnley et al. 2012) profiles.

The effects of taurine on performance have been somewhat mixed during high-intensity exercise (Milioni et al. 2016; Warnock et al. 2017; Batitucci et al. 2018; Waldron et al. 2018b) and others have found no change in lower-intensity steady-state performance or the physiological response to acute or chronic (7-day) taurine supplementation (1.66–3.32 g day−1) (Galloway et al. 2008; Rutherford et al. 2010). It is possible that inconsistency in the type of tests used, particularly during higher intensity exercise, have limited the current understanding. However, investigating parameters of the power–time relationship using a test, such as the 3MAOT, provides capacity to quantify a ‘gold standard’ marker of endurance exercise performance (Jones et al. 2019), which is tightly coupled to metabolic and cardiovascular control processes. Indeed, evaluation of the power–time relationship permits concomitant quantification of work capacity in severe-intensity domains (W′), which has not been determined following taurine supplementation. Understanding of the ways in which taurine supplementation might affect the two-component model would, therefore, reveal the domains of exercise that taurine supplementation is likely to enhance and extend the current understanding of its ergogenic role.

Therefore, this study investigated the effects of acute oral taurine ingestion on: (1) the power–time relationship using the 3MAOT; (2) time to exhaustion in the severe-intensity domain and (3) the estimated time to complete a range of fixed target intensities. It was hypothesised that oral taurine would alter the power–time relationship, thus increasing time to exhaustion at severe intensities.

Methods

Participants

Twelve recreationally active males (age 23 ± 3 years, stature 1.75 ± 0.61 m, body mass 75.5 ± 5.4 kg, \( \dot{V}{\text{O}}_{{ 2 {\text{max}}}} \) 54.9 ± 6.9 ml kg−1 min−1) took part in this study. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants. A priori sample sizes were calculated using G*Power (Version 3.0.10). Given the typical changes (Cohen’s d = 0.4; Waldron et al. 2018a) reported in endurance exercise after supplementation with taurine, a sample size of 12 was sufficient to identify differences between groups with a statistical power of 0.90. The participants were asked to arrive at the laboratory having not completed any exercise in the 48 h before testing, having abstained from alcohol and caffeine consumption in the 24 h prior. The participants were instructed to stay hydrated and consume a well-balanced meal no less than 2 h before testing, which was recorded and replicated across each day using a personal food diary. None of the participants were taking any other drugs or forms of supplementation during the study period. The participants consumed an additional 200 ml of fluid 1 h prior to exercise during each visit. Institutional ethical approval was granted for this study, which was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration.

Design

The participants reported to the laboratory on seven occasions at the same time of day (10:00 am ± 1 h). On visit 1, the participants were screened and performed an incremental ramp test to measure maximal oxygen consumption (\( \dot{V}{\text{O}}_{{ 2 {\text{max}}}} \)) and determine the linear factor for the subsequent CP tests. On visit 2, a familiarisation session was provided, where the participants completed a critical power test at the pre-determined linear factor. On visit 3, the participants completed their first experimental 3MAOT test on a cycle ergometer, which is hereafter referred to as the baseline CP. No supplement was provided at this visit. On visits 4–7, a double-blind, cross-over design was followed, whereby the participants completed either a 3MAOT or a time to exhaustion (TTE) at a fixed external power output 5% > the baseline CP. This meant that a TTE or 3MAOT was conducted per visit with one of two supplements (50 mg kg−1 taurine or 3 mg kg−1 maltodextrin placebo) randomly provided (TTE + taurine; TTE + placebo; 3MAOT + taurine; 3MAOT + placebo). Participants were assigned to their conditions between visits 4 and 7 using block randomisation online software (Urbaniak and Plous 2015). The dose of taurine was based on recent studies that have demonstrated its ergogenic effect (Waldron et al. 2018a; Warnock et al. 2017) and was prepared by a laboratory technician, who was uninvolved with the experimental procedures. The supplement was not checked for purity and was provided as received from the manufacturer. Each visit was separated by no more than 72 h for each participant, which was deemed sufficient to washout taurine based on half-life of between 0.7 and 1.4 h (Ghandforoush-Sattari et al. 2010).

Incremental ramp test

The participants performed an incremental exercise test on an electronically braked cycle ergometer (Lode Excalibur, Groningen, The Netherlands) to determine \( \dot{V}{\text{O}}_{{ 2 {\text{max}}}} \). After a 5-min, self-paced warm-up at an external workload of 100 W, the test was started at approximately 160 W and increased by 25 W every minute until volitional fatigue. Respiratory gas exchange was measured breath-by-breath using a mask connected to a gas analysis system (Jaeger Oxycon Pro, Viasys Healthcare, Hoechberg, Germany). The gas analyzer and flow turbine were calibrated before each test using a known gas mixture (15% O2 and 5% CO2) and a 3-l syringe, respectively (Hans Rudolph, Kansas City, KS). The test was terminated when cadence fell 10 rev min−1 below the participants chosen cadence for more than 10 s, \( \dot{V}{\text{O}}_{{ 2 {\text{max}}}} \) was determined as the highest mean value recorded over 30 s of the test. The ventilatory threshold (VT) was determined by two independent investigators using the V-slope method (Beaver et al. 1986).

Three-minute all-out test (3MAOT)

The 3MAOT was performed on the same cycle ergometer, which was adjusted to the participant based on their personal preferences recorded during the incremental test. The participants performed a warm-up at 50 W of external power for 5 min, followed by 5 min of seated rest (no pedalling) on the ergometer. In the next stage, the participant cycled in isokinetic mode (unloaded) on the ergometer for 2 min and 50 s at a cadence of 90 rev min−1, followed by a 10-s period of 110 rev min−1. A countdown was given in the last 5 s of the isokinetic phase to lead in to the 3MAOT, which was performed in linear mode. The participant’s linear factor was determined based on the mechanical power output 50% between VT and \( \dot{V}{\text{O}}_{{ 2 {\text{max}}}} \), which was achieved upon reaching their preferred cadence recorded during the incremental test (Vanhatalo et al. 2007) [linear factor = power (W)/cadence (rev min−1)2]. The participants were given non-specific verbal encouragement throughout the test by the investigators, without feedback of time to avoid pacing. The test was followed by 5-min recovery at 50 W. Peak power was determined as the highest external power maintained over a 1-s period. The end-power, hereafter referred to as the CP, was determined as the average external power sustained during the final 30 s of the test. The WEP was determined as the amount of external work (kJ) performed above the CP during the 3-min test. At the beginning (pre-warm-up) and 4 min after the end of the CP test, a capillary blood sample was collected from the finger to measure the change in blood lactate concentration (B[La] mmol l−1) using a calibrated analyser (Biosen C Line, EKF diagnostic GmbH, Barleben, Germany), with a coefficient of variation of 1.5%.

Time to exhaustion (TTE) 5% > critical power

After a 5-min warm-up at 100 W, a TTE was performed on the same ergometer at a power output 5% > the CP, as determined at the baseline visit. It was deemed appropriate to use these values to demarcate the severe-intensity domain, as the participants were familiarised and the coefficient of variation for the 3MAOT end-power was commensurate with published literature between the familiarisation and baseline visit (< 3.3% CV; Wright et al. 2017). The CV% for TTE 5% > CP has been previously determined as 3.7% in our laboratory with recreationally active participants. The participants were told to maintain their preferred cadence for as long as possible at the given power output. Exhaustion was determined by a drop in cadence of 10 rev min−1 below the participants chosen rate for more than 10 s. Non-specific verbal encouragement was provided throughout all tests.

Estimation of target work

The CP and WEP values obtained in the 3MAOT were used to predict the time required to complete a series of work-done targets of: 50,100,150 and 200 kJ, using the following equation:

where Tlim is the limit of tolerance, W is the target work done (50–200 kJ), WEP and CP were the work end power (kJ) and critical power (W) determined from the respective tests. The chosen work-done targets were deemed to reflect the power–duration relationship within the severe-intensity domain (Jones et al. 2010).

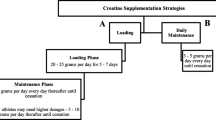

Supplementation

All of the supplements were prepared in a powder form and measured using an analytical balance (Precisa 125A, Precisa Gravimetrics AG, Zurich, Switzerland) for subsequent ingestion in gelatine capsules. The capsules contained one of the following: taurine (50 mg kg−1 body mass) or placebo (3 mg kg−1 body mass maltodextrin). Participants’ body mass was taken prior to each trial to measure the correct dose and the supplements were balanced such that an equal number of capsules were ingested between conditions. The dosages of taurine followed that recommended as safe, tolerable and ergogenic (Waldron et al. 2018a, c) and were all sourced from the same company (My Protein, Manchester, UK). After ingestion, the participants rested in a seated position for 1.5 h in a quiet room and were observed by the investigators. The 1.5-h timing was chosen as this permitted exercise to commence across the period of peak plasma availability of taurine after oral administration (Ghandforoush-Sattari et al. 2010).

Statistical analysis

A one-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to evaluate the effects of condition (baseline, taurine or placebo) on parameters of the power–time relationship (WEP, CP, peak power). A paired samples t test was used to assess the effects of condition (taurine or placebo) on the TTE at 5% > CP and the change in B[La] from pre–post-test. A two-way repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to evaluate the effects of condition on the estimated time (Tlim) at various work-done targets (100–200 kJ). Greenhouse–Geisser corrections were used when the assumption of sphericity was violated. Significant interactions were followed up using Bonferroni tests to identify pairwise differences. Statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05 and all analyses were performed on IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 21, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

There were no trial order effects in the current study (P > 0.05). Post-study, the participants were asked to guess the order of supplements with respect to visits 4–7. The correct order of all four conditions was correctly guessed twice (16.7%), with two further participants correctly guessing three of four conditions (16.7%). The remainder of participants correctly guessed none (33.3%), one (8.3%) or two (25%) of the four conditions.

Three-minute all-out test (3MAOT)

During the 3MAOT, there was an effect of the supplement on the CP [F(2,22) = 20.4, P < 0.001], with post hoc tests revealing differences between the taurine and baseline (P = 0.001) or placebo (P = 0.003) conditions. Similarly, peak power (F(2,22) = 8.2, P = 0.012) was highest in the taurine group, compared to baseline (P = 0.035) and placebo (F = 0.048) conditions. WEP was not affected by supplement, despite approaching significance [F(2,22) = 3.4, P = 0.079]. There were no differences (P > 0.05) between the baseline and placebo conditions for any measured variable (Fig. 1). The delta values for baseline–placebo, baseline–taurine and placebo–taurine for critical power (− 4.2 ± 10.1 W; 19.0 ± 13.3 W; − 14.8 ± 12.8 W, respectively), peak power (− 3.7 ± 21.2 W; − 65.4 ± 76.7 W; − 65.6 ± 71.1 W, respectively) and WEP (− 0.5 ± 0.14 kJ; 2.1 ± 3.4 kJ; − 1.6 ± 3.4 kJ, respectively) are presented in Fig. 1b, d, f, respectively. Figure 2 shows this for a representative participant.

Exercise in the severe-intensity domain

Time to exhaustion at 5% > CP was increased in the taurine condition compared to the placebo [t(11) = 4.4, P = 0.001]. A two-way ANOVA revealed further effects of taurine on Tlim [F(1,11) = 29.8, P < 0.001], which interacted with work targets [F(3,33) = 16.3, P = 0.002]. Post hoc tests demonstrated differences between taurine and placebo conditions across all work targets (P < 0.001) (Figs. 3, 4).

Blood lactate changes across the 3MAOT

There was an effect of the supplement on the change in B[La] from pre-to-post 3MAOT [F(2,22) = 5.9, P = 0.008], with differences between taurine and placebo (P = 0.007) but not baseline (P = 0.055) (Fig. 5).

Discussion

The primary aim of this paper was to investigate the effects of oral taurine supplementation on parameters of the power–time relationship during the 3MAOT. We found ~ 15 W increases in the CP compared to placebo but no significant change in the WEP, suggesting that the effects of taurine might be biased towards the oxidative component of the two-component CP bioenergetics model. However, the differences in WEP (2 kJ) approached significance (P = 0.079) and contributed toward the consistently improved Tlim across a range of work targets. Indeed, the TTE, conducted at a power output 5% > baseline CP, was also significantly improved (1.7 min) and explained by the effects of taurine on the severe-intensity threshold. Collectively, these findings are the first to show the contribution of taurine supplementation to exercise performed in the severe-intensity domain, thereby highlighting the possible roles of taurine in muscle bioenergetics or cardiorespiratory control processes.

The increases in CP found here support the suggestions of recent meta-analyses, where the consumption of isolated oral taurine (Waldron et al. 2018a), or as part of an energy drink (Souza et al. 2017), was reported to enhance endurance performance. Indeed, an increase of 15 W in the severe-intensity boundary could be significant for endurance athletes. However, the ergogenic effects of taurine were, perhaps, most effectively demonstrated via the improved TTE and estimated Tlim across a number of work targets (Figs. 3, 4). TIim across these fixed work targets is determined by a combination of the CP and WEP. Thus, changes in Tlim can be facilitated by both aerobically and anaerobically based metabolic control processes. For example, whilst exercise > CP is not entirely dependent on non-oxidative energy pathways (Vanhatalo et al. 2010), inexorable falls in muscle pH and concomitant depletion of PCr stores have been reported (Jones et al. 2008). As might be anticipated, exercise at these intensities is also associated with increased type II fibre recruitment in animal models (Copp et al. 2010). Taurine supplementation could logically assist with offsetting these sources of fatigue, particularly in relation to the enhanced severe-intensity exercise capacity and B[La] responses reported herein. Previous studies have highlighted the preferential action of taurine in the potentiation of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) of type I and II muscle fibres, where it can improve force generation or attenuate fatigue-induced force losses (Bakker and Berg 2002; Hamilton et al. 2006; Goodman et al. 2009; Dutka et al. 2014). Therefore, taurine supplementation could feasibly offset the decay of muscle force (particularly among glycolytic, fatigable fibres) observed during exercise testing. Furthermore, regulatory effects of taurine have been identified on voltage-gated chloride (ClC-1) in striated rodent muscle cells (Conte et al. 1987). Thus, it is feasible that the effect on membrane stabilisation might also translate to the control of muscle function during acute fatigue, which is characterised by dysregulated membrane excitability (Fauler et al. 2012). Based on our findings, we contend that the inconsistent results in relation to taurine’s ergogenic capacity, to date, could be partly explained by the limited and variable modes of exercise adopted. The dual effects of taurine on both W′ and CP appear to combine to enhance severe-intensity exercise capacity, when quantified using a valid and reliable, gold standard testing procedure. Further work is required to establish why severe-intensity exercise is augmented following taurine ingestion.

Whilst an abundant body of research supports the ergogenic role of taurine, there are a few studies that have reported trivial effects on performance (Rutherford et al. 2010; Milioni et al. 2016; Ward et al. 2016). The closest of these to the current study (Milioni et al. 2016) reported ‘unclear’ effects on the maximal accumulated oxygen deficit (MAOD), which is a measure of anaerobic capacity and a value that is reported to relate to the WEP (Hill and Smith 1993, 1994). It is interesting to contrast these findings with the changes found here in the power–time relationship, since our results are perhaps more appropriately explained by the prevailing opinion that work done above the CP is not equivalent to the anaerobic capacity and more closely relates to a general exercise tolerance and delayed fatigue in the severe-intensity domain (Vanhatalo et al. 2010; Jones and Vanhatalo 2017). Indeed, the CP has been described as a ‘fatigue threshold’ (Poole et al. 2016), demarcating a boundary of tolerable exercise intensity. This interpretation is more in keeping with the ergogenic roles of taurine, which are commonly attributed to alterations in fuel utilisation (De Carvalho et al. 2018), improved mechanical efficiency (Paulucio et al. 2017) or efficiency of ATP turnover in the muscle cell (Hansen et al. 2010). Each of these mechanisms has potential to improve exercise tolerance across a range of intensities and could certainly support the 15-W change in CP. Further work to establish the capacity of taurine to affect skeletal muscle ion handling or metabolic processes in vivo is necessary.

In addition to its roles in skeletal muscle, taurine is active in smooth muscle and endothelial cells of the vasculature, acting directly on potassium channels (Abebe and Mozaffari 2011), leading to improvements in vascular function (Sun et al. 2016). The CP is strongly related to the number of capillary contacts in both type I and II fibres of humans (Mitchell et al. 2018) and there is a dependency of the CP on muscle blood flow (Broxterman et al. 2015). Therefore, such mechanisms might have supported its increase after taurine supplementation. In the skeletal cells of mice, taurine has also been shown to control the rate of glycolytic flux (Takahashi et al. 2016), thus inferring a direct role in the control of metabolic pathways that are known determinants of high-intensity performance—the perturbation of which might lead to premature fatigue (Poole et al. 1988). It is the combination of these effects that we propose as an explanation for the concurrent improvements in both elements of the two-component model. Whilst a reciprocity between the CP and W′ is often reported as a result of dietary or training interventions (Jones and Vanhatalo 2017), supplements capable of participating in a variety of biological processes (i.e. cardiovascular, metabolic) are more likely to have combined effects on the power–time relationship.

The effect of oral taurine on time-trial performance (as opposed to capacity testing) has also been inconsistent, which is surprising given the clear roles established herein. For example, Ward et al. (2016) reported no effects of taurine on 4-km cycling time-trial performance, yet Balshaw et al. (2013) found improvements in 3-km time-trial running. The energetics of exercise across these distances relies heavily on capacity in the severe-intensity domain (Lacour et al. 1990) and, based on the current results, we would anticipate clear effects on closed-loop events of this distance. Indeed, the changes in severe-intensity exercise observed here (TTE and Tlim) are comparable or larger than those elicited by ischemic pre-conditioning (Griffin et al. 2018), beetroot juice (Kelly et al. 2013), beta alanine (Black et al. 2018) and caffeine (Silveira et al. 2018). Therefore, the reason for the discrepancy in findings between individual studies is unclear, but could relate to the range of doses and supplementation periods used or the training status of the participants (Waldron et al. 2018a). The participants of the current study were recreationally active, with a history of competitive sport but were not currently competitively trained. This might also explain the magnitude of the change in performance, since muscle taurine content is lower at baseline among untrained individuals (Graham et al. 1995). The type of research design has also varied between studies, with some including an additional group who are told they are receiving taurine but do not (see Rutherford et al. 2010). This was not included in the current study, but might have ensured that the effects were not the result of placebo effects. Future research should be designed to directly address these problems.

From a practical perspective, the results of this study support others in demonstrating the ergogenic effect of taurine on exercise tolerance and infer that a single supplement of taurine at a dose of 50 mg kg−1 body mass could improve performance across a range of exercise intensities. Therefore, an adult weighing 70 kg would require a dose of 3.5 g 1.5–2 h before training or competition to achieve an ergogenic effect. There have been no adverse side-effects reported across studies using doses up to 6 g (Waldron et al. 2018c), inferring the safety and tolerability of this supplement. The effects of taurine on endurance performance are fairly well-established among recreational athletes but, to date, there has been no work carried out on elite-level athletes, which is necessary to develop an understanding of the scope of taurine’s ergogenic effects.

Conclusion

Acute supplementation of 50 mg kg−1 of taurine increased exercise tolerance within the severe-intensity domain among recreationally active participants. The increase in CP supports the reported roles of taurine on the oxidative energy system and, in combination with 2 kJ changes in WEP, estimated performance would be expected to improve at a range of severe intensities.

References

Abebe W, Mozaffari MS (2011) Role of taurine in the vasculature: an overview of experimental and human studies. Am J Cardiovasc Dis 1:293–311

Bakker AJ, Berg HM (2002) Effect of taurine on sarcoplasmic reticulum function and force in skinned fast-twitch skeletal muscle fibres of the rat. J Physiol 538:185–194

Balshaw T, Bampouras T, Barry T, Sparks S (2013) The effect of acute taurine ingestion on 3-km running performance in trained middle-distance runners. Amino Acids 44:555–561

Batitucci G, Terrazas SIBM, Nóbrega PM, de Carvalho F, Papoti M, Marchini JS, da Silva ASR, de Freitas EC (2018) Effects of taurine supplementation in elite swimmers performance. Motriz Revista de Educação Física 24:e1018137

Beaver WL, Wasserman K, Whipp BJ (1986) A new method for detecting anaerobic threshold by gas exchange. J Appl Physiol 60:2020–2027

Black MI, Jones AM, Morgan PT, Bailey SJ, Fulford J, Vanhatalo A (2018) The effects of β-alanine supplementation on muscle pH and the power–duration relationship during high-intensity exercise. Front Physiol 9:111. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.00111

Broxterman RM, Ade CJ, Craig JC, Wilcox SL, Schlup SJ, Barstow TJ (2015) Influence of blood flow occlusion on muscle oxygenation characteristics and the parameters of the power–duration relationship. J Appl Physiol 118:880–889

Burnley M, Vanhatalo A, Jones AM (2012) Distinct profiles of neuromuscular fatigue during muscle contractions below and above the critical torque in humans. J Appl Physiol 113:215–223

Cheng CF, Hsu WC, Kuo YH, Shih MT, Lee CL (2016) Caffeine ingestion improves power output decrement during 3-min all-out exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol 116:1693–1702

Conte CD, Franconi F, Mambrini M, Bennardini F, Failli P, Bryant SH et al (1987) The action of taurine on chloride conductance and excitability characteristics of rat striated muscle fibers. Pharmacol Res Commun 19:685–701

Copp SW, Hirai DM, Musch TI, Poole DC (2010) Critical speed in the rat: implications for hindlimb muscle flow distribution and fibre recruitment. J Physiol 588:5077–5087

De Carvalho FG, Barbieri RA, Carvalho MB, Dato CC, Campos EZ, Gobbi RB et al (2018) Taurine supplementation can increase lipolysis and affect the contribution of energy systems during front crawl maximal effort. Amino Acids 50:189–198

Dekerle J, Brickley G, Hammond AJ, Pringle JS, Carter H (2006) Validity of the two-parameter model in estimating the anaerobic work capacity. Eur J Appl Physiol 96:257–264

Dutka T, Lamboley C, Murphy R, Lamb G (2014) Acute effects of taurine on sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ accumulation and contractility in human type I and type II skeletal muscle fibers. J Appl Physiol 117:797–805

Fauler M, Jurkat-Rott K, Lehmann-Horn F (2012) Membrane excitability and excitation-contraction uncoupling in muscle fatigue. Neuromuscul Disord 3:162–167

Galloway SD, Talanian JL, Shoveller AK, Heigenhauser GJ, Spriet LL (2008) Seven days of oral taurine supplementation does not increase muscle taurine content or alter substrate metabolism during prolonged exercise in humans. J Appl Physiol 105:643–651

Ghandforoush-Sattari M, Mashayekhi S, Krishna CV, Thompson JP, Routledge PA (2010) Pharmacokinetics of oral taurine in healthy volunteers. J Amino Acids. https://doi.org/10.4061/2010/346237

Goodman CA, Horvath D, Stathis C, Mori T, Croft K, Murphy RM et al (2009) Taurine supplementation increases skeletal muscle force production and protects muscle function during and after high-frequency in vitro stimulation. J Appl Physiol 107:144–154

Graham TE, Turcotte LP, Kiens B, Richter EA (1995) Training and muscle ammonia and amino acid metabolism in humans during prolonged exercise. J Appl Physiol 78:725–735

Griffin PJ, Ferguson RA, Gissane C, Bailey SJ, Patterson SD (2018) Ischemic preconditioning enhances critical power during a 3 minute all-out cycling test. J Sports Sci 36:1038–1043

Hamilton E, Berg H, Easton C, Bakker A (2006) The effect of taurine depletion on the contractile properties and fatigue in fast-twitch skeletal muscle of the mouse. Amino Acids 31:273–278

Hansen S, Andersen M, Cornett C, Gradinaru R, Grunnet N (2010) A role for taurine in mitochondrial function. J Biomed Sci 17(Suppl 1):S23

Hill DW, Smith JC (1993) A comparison of methods of estimating anaerobic work capacity. Ergonomics 36:1495–1500

Hill DW, Smith JC (1994) A method to ensure the accuracy of estimates of anaerobic capacity derived using the critical power concept. J Sports Med Phys Fitn 34:23–37

Huxtable RJ (1992) Physiological actions of taurine. Physiol Rev 72:101–163

Jones AM, Vanhatalo A (2017) The ‘critical power’ concept: applications to sports performance with a focus on intermittent high-intensity exercise. Sports Med 47:65–78

Jones AM, Wilkerson DP, DiMenna F, Fulford J, Poole DC (2008) Muscle metabolic responses to exercise above and below the “critical power” assessed using 31P-MRS. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294:585–593

Jones AM, Vanhatalo A, Burnley M, Morton RH, Poole DC (2010) Critical power: Implications for determination of VO2max and exercise tolerance. Med Sci Sports Exerc 42:1876–1890

Jones AM, Burnley M, Black MI, Poole DC, Vanhatalo A (2019) The maximal metabolic steady state: redefining the ‘gold standard’. Physiol Rep 7:e14098

Kelly J, Vanhatalo A, Wilkerson DP, Wylie LJ, Jones AM (2013) Effects of nitrate on the power–duration relationship for severe-intensity exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 45:1798–1806

Lacour JR, Padilla-Magunacelaya S, Barthélémy JC, Dormois D (1990) The energetics of middle-distance running. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 60:38–43

Lim ZIX, Singh A, Leow ZZX, Arthur PG, Fournier PA (2018) The effect of acute taurine ingestion on human maximal voluntary muscle contraction. Med Sci Sports Exerc 50:344–352

Machado MV, Batista AR, Altimari LR, Fontes EB, Triana RO, Okano AH et al (2010) Effect of caffeine intake on critical power model parameters determined on a cycle ergometer. Rev Bras Cineantropom Desempenho Hum 12:49–54

Milioni F, Malta ES, Rocha LG, Mesquita CA, Zagatto EC (2016) Acute administration of high doses of taurine does not substantially improve high-intensity running performance and the effect on maximal accumulated oxygen deficit is unclear. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 41:498–503

Mitchell EA, Martin NRW, Bailey SJ, Ferguson RA (2018) Critical power is positively related to skeletal muscle capillarity and type I muscle fibers in endurance trained individuals. J Appl Physiol. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.01126.2017

Miura A, Kino F, Kajitani S, Sato H, Fukuba Y (1999) The effect of oral creatine supplementation on the curvature constant parameter of the power–duration curve for cycle ergometry in humans. Jpn J Physiol 49:169–174

Paulucio D, Costa BM, Santos CG, Nogueira F, Koch A, Machado M et al (2017) Taurine supplementation improves economy of movement in the cycle test independently of the detrimental effects of ethanol. Biol Sport 34:353–359

Poole DC, Ward SA, Gardner GW, Whipp B (1988) Metabolic and respiratory profile of the upper limit for prolonged exercise in man. Ergonomics 31:1265–1279

Poole DC, Burnley M, Vanhatalo A, Rossiter HB, Jones AM (2016) Critical power: an important fatigue threshold in exercise physiology. Med Sci Sports Exerc 48:2320–2334

Rutherford JA, Spriet LL, Stellingwerff T (2010) The effect of acute taurine ingestion on endurance performance and metabolism in well-trained cyclists. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 20:322–329

Silveira R, Andrade-Souza VA, Arcoverde L, Tomazini F, Sansonio A, Bishop DJ et al (2018) Caffeine increases work done above critical power, but not anaerobic work. Med Sci Sports Exerc 50:131–140

Smith JC, Stephens DP, Hall EL, Jackson AW, Earnest CP (1998) Effect of oral creatine ingestion on parameters of the work rate–time relationship and time to exhaustion in high-intensity cycling. Eur J Appl Physiol 77:360–365

Souza DB, Del Coso J, Casonatto J, Polito MD (2017) Acute effects of caffeine-containing energy drinks on physical performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Nutr 56:13–27

Sun Q, Wang B, Li Y, Sun F, Li P, Xia W et al (2016) Taurine supplementation lowers blood pressure and improves vascular function in prehypertension. Hypertension 67:541–549

Takahashi Y, Tamura Y, Matsunaga Y, Kitaoka Y, Terada S, Hatta H (2016) Effects of taurine administration on carbohydrate metabolism in skeletal muscle during the postexercise phase. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol 62:257–264

Urbaniak GC, Plous S (2015) Research randomizer (version 4.0) [computer software]. http://www.randomizer.org/. Accessed 3 April 2018

Vanhatalo A, Jones AM (2009) Influence of creatine supplementation on the parameters of the “all-out critical power test. J Exerc Sci Fit 7:9–17

Vanhatalo A, Doust JH, Burnley M (2007) Determination of critical power using a 3-min all-out cycling test. Med Sci Sport Exerc 39:548–555

Vanhatalo A, Fulford J, DiMenna FJ, Jones AM (2010) Influence of hyperoxia on muscle metabolic responses and the power–duration relationship during severe-intensity exercise in humans: a 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Exp Physiol 95:528–540

Vanhatalo A, Black MI, DiMenna FJ, Blackwell JR, Schmidt JF, Thompson C et al (2016) The mechanistic bases of the power–time relationship: muscle metabolic responses and relationships to muscle fibre type. J Physiol 594:4407–4423

Waldron M, Patterson SD, Tallent J, Jeffries O (2018a) The effects of an oral taurine dose and supplementation period on endurance exercise performance in humans: a meta-analysis. Sports Med 48:1247–1253

Waldron M, Knight F, Tallent J, Patterson SD, Jeffries O (2018b) The effects of taurine on repeat sprint cycling after low or high cadence exhaustive exercise in females. Amino Acids 50:663–669

Waldron M, Patterson SD, Tallent J, Jeffries O (2018c) The effects of oral taurine on resting blood pressure in humans: a meta-analysis. Curr Hypertens Rep 20:81

Ward R, Bridge CA, McNaughton LR, Sparks SA (2016) The effect of acute taurine ingestion on 4-km time trial performance in trained cyclists. Amino Acids 48:2581–2587

Warnock R, Jeffries O, Patterson S, Waldron M (2017) The effects of caffeine, taurine, or caffeine-taurine co-ingestion on repeat-sprint cycling performance and physiological responses. Int J Sport Physiol Perform 12:1341–1347

Wright J, Bruce-Low S, Jobson SA (2017) The reliability and validity of the 3-min all-out cycling critical power test. Int J Sports Med 38:462–467

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Handling Editor: S. W. Schaffer.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Waldron, M., Patterson, S.D. & Jeffries, O. Oral taurine improves critical power and severe-intensity exercise tolerance. Amino Acids 51, 1433–1441 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-019-02775-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-019-02775-6