Abstract

We investigate the seismicity rate behaviour in and around Greece during 2009, seeking significant changes in rate preceding larger events. For individual larger events it is difficult to clearly distinguish precursory rate changes from other, possibly unrelated, variations in seismicity. However, when we aggregate seismicity data occurring within a radius of 10 km and in a 50-day window prior to earthquakes with, e.g. magnitude ≥3.5, the resulting aggregated time series show a clearly increasing trend starting 2–3 weeks prior to the “mainshock” time. We apply statistical tests to investigate if the observed behaviour may be simply consistent with random (poissonian) variations, or, as some earlier studies suggest, with clustering in the sense that high activity rates at some time may imply increased rates later, and thus (randomly) greater probability of larger coming events than for periods of lower seismicity. In this case, rate increases have little useful predictive power. Using data from the entire catalogue, the aggregated rate changes before larger events are clearly and strongly statistically significant and cannot be explained by such clustering. To test this we choose events at random from the catalogue as potential “mainshocks”. The events preceding the randomly chosen earthquakes show less pronounced rate increases compared to the observed rate changes prior to larger events. Similar behaviour is observed in data sub-sets. However, statistical confidence decreases for geographical subsets containing few “mainshocks” as it does when data are weighted such that “mainshocks” with many preceding events are strongly downweighted relative to those with fewer. The analyses suggest that genuine changes in aggregated rate do occur prior to larger events and that this behaviour is not due to a small number of mainshocks with many preceding events dominating the analysis. It does not automatically follow that it will be possible to routinely observe precursory changes prior to individual larger events, but there is a possibility that this may be feasible, e.g. with better data from more sensitive networks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction—Origin of the Conceptual Framework

The temporal and spatial distribution of seismicity can be analysed using various tools. One specific target is to identify possible earthquake sequences before or after large events. Such studies may be able to reveal stress accumulation and concentration prior to the main event, and the properties of aftershock sequences may provide important insights into the physical processes steering earthquake occurrence, both in the specific area and more generally. A long-term goal is to develop a fully adequate physical model of the processes leading to, and stimulated by, earthquakes. As a step towards physical modelling, various types of statistical modelling may be applied. The natural approach is to regard earthquakes as “point processes” in the sense that they occur at distinct positions and at specific times (Ogata 1999; Vere-Jones et al. 2005 among others).

Clearly, earthquake sequences reflect important properties of earthquake processes, including issues which we do not yet fully understand. It is empirically well-established that seismicity occurrence rates after a large earthquake often decay to some “background” level, approximately according to the empirical Omori law (Toda et al. 2002, 2005; Utsu et al. 1995 among others). Foreshocks are frequently observed, but the division between foreshocks, mainshocks and aftershocks is not always clear. Generally foreshocks are only identified as such after the succeeding mainshock has occurred (Bouchon et al. 2013; Helmstetter et al. 2003; Helmstetter and Sornette 2003). Conceptually, it is also reasonable to envisage that an area subjected to shear loading may deform, inducing earthquakes, or lock, accumulating stress which may later lead to a larger event. Therefore, seismic quiescence may indicate the risk of a coming large event, although it may be difficult to distinguish true quiescence from other phenomena, such as aftershock sequence rate decay. There have been many attempts to identify temporal patterns in seismicity aimed at identifying foreshocks and thus providing warnings of coming large events. There have been some, apparently convincing, successes, e.g. for Iceland (Bonafede et al. 2007; Stefánsson et al. 1993), but generally these methods have not worked well. That an Icelandic event could be (apparently) successfully predicted based on foreshock activity was partly because of the distinct tectonic situation in the South Iceland Lowlands and partly because the seismological system there is extremely sensitive (Wyss and Stefansson 2006). While high sensitivity is still unusual, many networks have been greatly improved. Increased sensitivity by one step in magnitude means about ten times the total number of recorded events. This could help in the quest to find seismicity patterns indicative of foreshocks (Mignan 2014).

Here, we study the seismicity rate behaviour prior to relatively larger events that occurred in Greece during 2009. Earlier studies on the same area include those of Papazachos (1974) and Papazachos et al. (1982) who investigated foreshock and aftershock sequences of strong shallow earthquakes. Estimating (retrospectively) the b parameter of the Gutenberg–Richter (G–R) distribution of magnitudes, they observed different b values prior to and after individual mainshocks. Similar results, concerning observed decreases of b value during preshock sequences, were found by Papadopoulos et al. (2006) who studied the temporal evolution of a more recent earthquake sequence that occurred in the East Aegean Sea. Later studies by Drakatos (2000) and the references therein focused on periods of relative seismic quiescence as potential precursory phenomena before strong aftershocks. Papadopoulos et al. (2000) and Orfanogiannaki and Papadopoulos (2004) published results related to precursory activity observed in the Corinth Gulf. They suggested that foreshocks usually occur during the last 4 months prior to strong events and within 30 km radius around their epicentre, with the highest probability for the mainshock occurrence found within the last 10 days of the foreshock period. They also estimated changes in the b-value, suggesting this to be a criterion useful for distinguishing foreshocks from swarm activity. Console et al. (2006) worked with data from Greece and applied statistical models on short and long time scales, while combining temporal and spatial modelling to investigate the activity prior to major events. Gospodinov et al. (2015) applied the Restricted Epidemic Type Aftershock Sequence (RETAS) model aiming to identify precursors and periods of relative quiescence prior to strong aftershocks and estimate the occurrence probabilities of new strong events in a sequence.

Below, we present results from a number of different methods aimed at identifying possible changes in the character of activity prior to larger events, using data from Greece. Note that we refer to “preshock sequences” to describe the seismic activity observed prior to specific larger events defined as “mainshocks”, within a given geographical area. If the radius and time window are small enough, these “preshocks” can plausibly be mechanically related to the coming “mainshocks”. We term such truly linked events “foreshocks”. Observed changes in the seismicity patterns related to potential “precursory activity” are often reported as such only retrospectively. In the data sets we have investigated, identifying earthquake events as true precursors to individual mainshocks can be difficult, because it is difficult to distinguish them from other types of “clustering” occurring “by chance” prior to the “mainshocks”, e.g. as part of an aftershock sequence that started earlier. In this case, even if our “mainshock” is part of an ongoing aftershock sequence, it is still appropriate to seek “foreshocks” manifested as temporary increasing rates in the generally decaying aftershock sequence. More details will be given in later sections.

2 Data—Sources for Catalogues—Case Studies

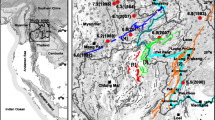

Following Marsan and Nalbant (2005), to investigate background seismicity and potential rate changes before relatively larger earthquakes, we produce individual seismicity catalogues for selected areas defined in accordance with known tectonics and observed seismicity. We used data from the Greek catalogue during 2009, provided online by the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (AUTh). The catalogue consisted of 4900 events (M L ≥ 2, manually reviewed by the staff of AUTh) located at depths down to 60 km. The stations used for the location of these events are shown in Fig. 1, with the majority of them operated by the Hellenic Unified Seismological Network (HUSN, D’Alessandro et al. 2011), whereas some of them belong to neighbouring networks (see http://geophysics.geo.auth.gr/ss/station_index_en.html for details). Few larger events (above M5) occurred in this period and the data are not dominated by one or a few major aftershock sequences. During 2009 the configuration of the seismic network was relatively stable. Our analysis requires that the number of events is sufficient for our data processing and that sufficiently long time periods before each “mainshock” are available to compare possible short-term rate changes to a reference rate (see Sect. 3). We present results from the whole of Greece and from two geographical subsets covering two of the most active areas of Greece (rectangles in Fig. 1). The normal faults surrounding the Corinth Gulf form a tectonic half-graben with high seismicity. Many large events have occurred in the past, some causing damage to nearby towns, motivating a dense seismic network. 903 events with M L ≥ 2 were recorded in that area during 2009. Lefkada and Cephalonia islands (in the Ionian sea) are the most seismically active areas of Greece, with strong earthquakes that occurred in the past (e.g. the M6.4 event in November 2015), and are associated with the Cephalonia transform fault (Karakostas et al. 2004). The subset used in that case consists of 438 events with M L ≥ 2.

Stations of the Hellenic Unified Seismological Network (HUSN) and neighbouring networks. The red rectangles show the geographical subsets, the southern Ionian Sea and the Corinth Gulf. Yellow arrows and lines show tectonic motions and features. NAF North Anatolian Fault, NAT North Aegean Trough, CTF Cephalonia Transform Fault

3 Aggregated Seismicity Data—Methods and Results

Inspection of the catalogue data (here, the Greek catalogue for 2009) did not reveal unambiguous precursory activity to individual larger events, so a reasonable question is if it is sensible to look for precursors at all. Therefore, we superimpose data from larger events. Mignan (2014) presented a meta-analysis on the ongoing debate regarding the possible prognostic value of foreshocks, in which he reviewed several studies, some including stacking earthquake sequences (see also Ogata et al. 1995 and the references therein). Here, we first define the magnitude threshold (M th) above which all the events (with magnitude ≥M th) are regarded as “mainshocks” occurring at time T 0. We refer to the magnitude of these “mainshocks” as M 0. The lower threshold we use, the more sequences will be aggregated. For the different magnitude thresholds we tried (e.g. M3.5, M4, M4.5), similar behaviour was observed in the stacked sequences. Below we present the results for M 0 ≥ 3.5.

Especially as our “mainshocks” may have rather different magnitudes, it is not immediately clear on what basis we should select the size of the region around each mainshock to be searched for possible precursors. Papadopoulos et al. (2000) and Orfanogiannaki and Papadopoulos (2004), who studied foreshock activity prior to strong events (M s > 4.5 and M s > 5) that occurred at the area of the Corinth Gulf, suggested that precursors might be found within 30 km radius from the epicentre of the mainshocks and can be observed during the last 4 months before each mainshock. Bouchon et al. (2013) and Marsan et al. (2014) used a radius equal to 50 km and a time window between 6 months to 1 year to investigate the precursory activity before M > 6 events. Considering that the magnitudes of our “mainshocks” are smaller than the ones used in the aforementioned studies, their choices were the upper limits for the radius and time window which we investigated (Fig. 2).

Aggregated preshock sequences for “mainshocks” of M 0 ≥ 3.5, for different radii. The inverse inter-event times of the common series in each case are shown in blue, as a proxy of the seismicity rate (events/day) and the corresponding average cumulative number of events of the normalised sequences is plotted in red

As genuine precursors, if they exist, must be in some way mechanically related to their mainshock, they must reasonably be rather close, which for smaller mainshocks probably means at most a few kilometres. By using a smaller radius, we increase the probability of the observed apparent foreshocks being mechanically related to the coming mainshock, but generally decrease the number of events included in each preshock sequence and thus the number of potential observed foreshocks. On the other hand, smaller windows imply that fewer sequences will be spatially or temporarily overlapping (whenever that is the case, only the sequence preceding the biggest “mainshock” is used). It could be argued that the radius used should depend on the mainshock magnitude. Our logic is, however, that as we ultimately seek to identify precursors before a mainshock (of unknown magnitude) has occurred, we should use a fixed radius. Note that because our calculations in practice compare activity rates within a defined geographical area and period before each “mainshock”, different system sensitivities and magnitudes of completeness should not be a significant problem.

To reduce possible major “contamination” by aftershocks of preceding large events, no “mainshock” was considered if there was a previous larger event within our time window and radius. If there are temporary rate increases due to aftershocks to larger aftershocks, but not directly related to our “mainshocks”, they should occur at random times prior to T 0. Those aftershocks will only lead to major problems if their rate is rather high so that they will be rather dominant in our aggregated data. The distribution of the number of events per “mainshock” in our analysis suggests that with our choice of radius and time window such possible problems should be limited.

Some results, produced using data from the whole of Greece, a time window of 100 days and different values for the radius around the “mainshock” epicentres, are shown in Fig. 2. Having selected events prior to each “mainshock”, we superimpose these data to produce an aggregated series of all potential precursors to all “mainshocks”. By plotting the inverse inter-event times of neighbouring events as a proxy of the seismicity rate (blue lines in Fig. 2), we can see that there is a clear increase in seismicity during the last few days before T 0. Chen and Shearer (2016) normalised the event occurrence by the duration of the precursory sequence and calculated the average cumulative density function of their precursory sequences to check if the acceleration behaviour they observed was dominated by a few large sequences. We instead normalised by the number of earthquakes in each sequence and the average cumulative number of events is shown in Fig. 2 (red curves), revealing a change of slope before T 0 in all cases, when the proxy of the seismicity rate for the aggregated series also increases.

4 Methods of Testing the Results—Applications

The significance of observed changes in aggregated foreshock data can be assessed using several tests based on data subsets and comparison with randomised models. We use data subsets based on, e.g. splitting the aggregated series in two random parts, into different magnitude bands and into geographical subareas (Sect. 5). If true seismicity changes are present, the first two methods should show similar results. As different geographical areas may genuinely show different behaviour, the third test is that of the generality of the observed behaviour.

We focus on the last 50 days of the aggregated series of the preshocks that occurred not further than 10 km from the “mainshock” epicentres. This time window includes the observed increasing trend prior to T 0 as shown in Fig. 2e, while the radius choice fulfills our criteria (see Sect. 3), also considering the smaller size of the geographical subareas (Fig. 1). An example of testing whether the apparent increasing rate is dominated by only a few events is shown in Fig. 3, where the group of “mainshocks” has been randomly split into two parts and the pre-sequences of each part are aggregated as before. If a single event dominated the observed rate increase, we would see the effect in only one of the subsets. If a few events dominate, then different random selections will likely show different behaviour. In all cases we investigated, apparent rate increases during approximately 20 days prior to T 0 were observed despite less data than in Fig. 2e.

Aggregated series corresponding to the last 50 days of the aggregated series shown in Fig. 2e (preshocks located within 10 km radius from the “mainshock” epicentres) for a random selection of half of the “mainshocks”, and the remainder. An increase in seismicity during the last days before T 0 is observed in all plots

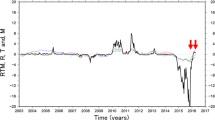

Thus, we are looking primarily for rate increases. Lower levels of aftershock sequence contamination do not invalidate our approach, as explained earlier (Sect. 3). However, we tested our technique also on a declustered version of our data. The catalogue for 2009 is not dominated by one or a few major aftershock sequences. To investigate the possible disturbing effect of the smaller aftershock sequences which are observed, we declustered using the methods of Reasenberg (1985). This identified 878 of 4900 events (whole of Greece) as aftershocks. The aggregation procedure was then repeated using the declustered catalogue (Fig. 4a). For comparison, the daily rate of a simulated homogeneous Poisson sequence with the same number of events is also plotted. The empirical curve shown climbs above the random sequence two weeks before T 0. Seismic data are often clustered not only in the sense of Omori-type aftershock sequences. According to the Gutenburg–Richter (G–R) distribution, more events imply a greater possibility of a larger event. In some statistical models, such as the Epidemic Type Aftershock Sequence (ETAS) model, every single event can trigger further aftershocks (and thus a small earthquake can occasionally trigger a bigger aftershock). An increase in seismicity rate may then be expected prior to larger events (Felzer et al. 2004; Helmstetter 2003), but this rate increase has no predictive power beyond the generality of the G–R relationship. In other words, the mainshock is related to a preceding rate increase, but only in a statistical sense via G–R. Thus, many rate increases will not lead to large events and they are essentially not useful precursors. It is, therefore, appropriate to test whether the observed acceleration of seismicity in the aggregated series could be due to the tendency of seismicity to cluster in time.

a “Mainshocks” of M 0 ≥ 3.5 from the declustered catalogue of Greece and their aggregated preshock sequences. The red line shows the average daily seismicity rate. For comparison, and to show the potential level of purely “random” variability, the black line shows the result of an equivalent poisson realisation. b Red line as in a, but using the raw (not declustered) catalogue. The same number of sequences are processed in the same way but with random events chosen as “mainshocks”. The blue line is the average of 100 such realisations, and the shaded area shows the empirical 95% confidence interval

A common methodology to assess the prognostic value of foreshocks includes a comparison of observations to what is predicted by cluster-type models (Bouchon et al. 2013; Marsan et al. 2014; Mignan 2014 for a review; Ogata and Katsura 2014). Synthetic stochastic data series based on a suitable space–time ETAS model may be compared to the empirical data. Statistically significant differences between the empirical and synthetic data could reveal precursory activity, which is not included in the ETAS model. One problem with many such approaches is that the ETAS model is assumed to be spatially and temporally constant, which may be a strong assumption given, e.g. that the magnitude of completeness in a given area may evolve over time. Below we present an approach designed to seek precursory activity and to be relatively insensitive to, e.g. changes in magnitude of completeness.

For each of our identified “mainshocks” we randomly selected one event from the surrounding area (within 20 km) and outside the time window used for the preshock sequences (i.e. the randomly chosen events occurred more than 50 days prior to each “mainshock”). Where the randomly selected earthquake had a larger preceding event within 50 days, it was rejected and a new event was randomly selected. The “preshock” sequences of one randomly selected event per “mainshock” were then aggregated. This procedure was repeated 100 times, allowing the calculation of mean rates and approximate empirical confidence limits. The results were then compared to the stacked preshock sequences of our identified “mainshocks” of M 0 ≥ 3.5. Such randomised tests allow the assessment of if observed rate changes are too large to be reasonably explained by ETAS-type random clustering.

The results of the randomised test are shown in Fig. 4b. The shaded area in this figure corresponds to the 95% confidence intervals in the sense that rate in 5% of the random realisations in this example lay above this value. The average daily rate of the aggregated series preceding the stronger “mainshocks” increases compared to the average rate of the randomly chosen aggregated series and this apparent acceleration of seismicity is also seen to exceed the confidence limits.

5 Geographical Subsets—Results

Next, we investigate two geographical subsets of the catalogue. These areas are geologically and seismologically different and have different network densities and completeness magnitudes. We chose two of the most seismically active areas in Greece: The southern Ionian Sea and the Corinth Gulf (Fig. 5a, b). As above, all events over M3.5, without a larger event just before, were classed as “mainshocks”, and their preshock sequences were aggregated. The aggregated series of both subsets are shown in Fig. 6, along with the average cumulative number of events after normalising each individual sequence by the corresponding number of earthquakes. Figure 7a, c corresponds to the analyses shown in Fig. 4a and b for the Ionian Sea and Fig. 7b and d for the Corinth Gulf. All graphs show an apparent increase in seismicity, clearly above that expected for Poissonian type behaviour.

Aggregated preshock sequences for “mainshocks” of M0 ≥ 3.5 for the subset of a the Ionian Sea and b the Corinth Gulf. The inverse inter-event times of the common series in each case are shown in blue and the corresponding average cumulative number of events of the normalised sequences is plotted in red

a, b “Mainshocks” of M0 ≥ 3.5 from the declustered catalogue of the Ionian Sea (a) and the Corinth Gulf (b). The red line shows the average daily seismicity rate. For comparison (as in Fig. 4) the black line shows the result of an equivalent poisson realisation. c, d Red line as in a and b, but using the raw (not declustered) catalogue of the Ionian Sea (c) and the Corinth Gulf (d). Blue line and shaded area as in Fig. 4

However, the randomised test of confidence is more ambiguous, with the data partly above and partly below these limits. For the well-monitored Corinth Gulf the increasing trend of seismicity is clear and at the 95% level not consistent with simple clustering, i.e. the data imply a causal mechanical relationship between the preshocks and the “mainshocks”. There are fewer events from the Ionian Sea, partly because the completeness magnitude there is higher as fewer small events are recorded. Here, the confidence limits suggest that it is not possible to robustly confirm that the rate increase cannot be explained by simple clustering, even though this rate increase is itself very clear.

6 Discussion

Several statistical approaches may be used when seismicity catalogues are available, as seen, e.g. in the studies of Marsan and Nalbant (2005) and Ogata (1999). Differences in the approaches may include different statistical models and either using complete or declustered data sets.

The simplest possibly relevant statistical model is a temporally homogeneous (Poisson) process (Toda et al. 2002 among others). Considerations of the mechanics of the situation, including concepts such as Coulomb stress transfer (Parsons 2005; Parsons et al. 2000; Stein et al. 1997; Toda et al. 1998, 2005) imply that some, especially neighbouring, large earthquakes are specifically interrelated, suggesting that a homogeneous model is likely to be at best an approximation. Additionally, it is well known that aftershock sequences mean that seismicity rates are often far from homogeneous (Felzer and Brodsky 2005; Marsan 2003). One approach is to try to identify and remove aftershocks, to produce a possibly near-homogeneous mainshock sequence (Gomberg et al. 2001; Kilb et al. 2000; Matthews and Reasenberg 1988; Wyss and Wiemer 2000), although results may be dependent upon the choice of methodology, such as declustering algorithms used.

Another way to describe the temporal patterns of seismicity is by means of cascade models (Felzer et al. 2015; Helmstetter et al. 2003). Testing data for consistency with an ETAS-type model can be complex, partly because of issues related to, e.g. data completeness. We can, however, rather easily test the internal consistency of the data relative to an ETAS model, with the randomised tests we described and applied in Sect. 4. In cascade models, an “acceleration” exists prior to larger events and may be observable (depending on the data). In one sense, there are then “foreshocks”. However, these contain essentially no predictive power for the coming larger event, which according to this concept is related to the foreshocks only in the statistical sense that higher rates imply a higher probability of future events, some few of which by chance will be large. It follows that we should expect some tendency for increased rate prior to larger earthquakes, even if there is no relationship between events other than the general G–R distribution. If this is the case, then we would expect to see similar rate increases before randomly selected small events as before larger ones. The results of this randomised test shown in Figs. 4 and 7 indicate that the stacked sequences of the events preceding the randomly chosen smaller earthquakes show much less pronounced rate increase than for our “mainshocks”. There is an increase in observed rate prior to smaller events, but this is not larger than what we might expect from ETAS-type clustering.

7 Conclusions

Previous studies related to precursory phenomena in the area of Greece (e.g. Orfanogiannaki and Papadopoulos 2004; Papadopoulos et al. 2000; Papazachos 1974) presented evidence that foreshock activity took place prior to several strong earthquakes that occurred in the past. Although our data are insufficient to reliably investigate individual events, we seek generic behaviour in activity observed before “mainshocks” and we investigate whether “foreshock” activity can be distinguished from other types of “clustering”. Assuming that there may be an underlying common behaviour for all events, we stack or aggregate data to seek patterns.

During the time preceding larger events we could in principle observe either (a) no changes in the seismicity rate, (b) a period of decreased rate (“quiescence”), (c) an “acceleration” (increase in seismicity rate) with deterministic components (accumulation of near-critical stress on the fault) or (d) a “stochastic” acceleration, i.e. all events can be regarded as aftershocks to earlier events, with a probability of occurrence steered (presumably) by the modified Omori law and magnitudes randomly selected from a G–R type distribution (ETAS). For our data we can reject the first two cases. Using the inverse inter-event times of subsequent events as a proxy of seismicity rate, an increasing trend was revealed in the aggregated series, observable from a few (~20) days prior to the occurrence time of our “mainshocks”.

For most of our data, the hypothesis that the observed aggregated acceleration can be explained by an ETAS-type model was rejected with over 95% confidence. Our approach is relatively insensitive to many problems, such as data incompleteness and the assumptions we make are minor relative to most similar analyses. The results indicate that this is a necessary, but not sufficient at the confidence level, test for the hypothetical agreement of the data with an ETAS model of the defined type.

If there are deterministic changes in seismicity rate prior to larger events then this implies that there may be some possibility of using seismicity data for short-term prediction. However, to achieve this we must better understand the possible patterns which are there, and to do this we probably need significantly more data, i.e. significantly more sensitive seismic networks.

References

Bonafede, M., Ferrari, C., Maccaferri, F., & Stefánsson, R. (2007). On the preparatory processes of the M6.6 earthquake of June 17th, 2000, in Iceland. Geophysical Reseach Letters, 34, L24305. doi:10.1029/2007GL031391.

Bouchon, M., Durand, V., Marsan, D., Karabulut, H., & Schmittbuhl, J. (2013). The long precursory phase of most large interplate earthquakes. Nature Geoscience, 6, 299–302. doi:10.1038/ngeo1770.

Chen, X., & Shearer, P. M. (2016). Analysis of foreshock sequences in California and implications for earthquake triggering. Pure and Applied Geophysics, 173, 133–152. doi:10.1007/s00024-015-1103-0.

Console, R., Rhoades, D. A., Murru, M., Evison, F. F., Papadimitriou, E. E., & Karakostas, V. G. (2006). Comparative performance of time-invariant, long-range and short-range forecasting models on the earthquake catalogue of Greece. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 111, B09304. doi:10.1029/2005JB004113.

D’Alessandro, A., Papanastassiou, D., & Baskoutas, I. (2011). Hellenic Unified Seismological Network: An evaluation of its performance through SNES method: HUSN performance through SNES method. Geophysical Journal International, 185, 1417–1430. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2011.05018.x.

Drakatos, G. (2000). Relative seismic quiescence before large aftershocks. Pure and Applied Geophysics, 157, 1407–1421. doi:10.1007/PL00001126.

Felzer, K. R., Abercrombie, R. E., & Ekström, G. (2004). A common origin for aftershocks, foreshocks, and multiplets. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 94, 88–98. doi:10.1785/0120030069.

Felzer, K. R., & Brodsky, E. E. (2005). Testing the stress shadow hypothesis. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 110, B05S09. doi:10.1029/2004JB003277.

Felzer, K. R., Page, M. T., & Michael, A. J. (2015). Artificial seismic acceleration. Nature Geoscience, 8, 82–83. doi:10.1038/ngeo2358.

Gomberg, J., Reasenberg, P. A., Bodin, P., & Harris, R. A. (2001). Earthquake triggering by seismic waves following the Landers and Hector Mine earthquakes. Nature, 411, 462–466. doi:10.1038/35078053.

Gospodinov, D., Karakostas, V., & Papadimitriou, E. (2015). Seismicity rate modeling for prospective stochastic forecasting: The case of 2014 Kefalonia, Greece, seismic excitation. Natural Hazards. doi:10.1007/s11069-015-1890-8.

Helmstetter, A. (2003). Foreshocks explained by cascades of triggered seismicity. Journal of Geophysical Research. doi:10.1029/2003JB002409.

Helmstetter, A., Ouillon, G., & Sornette, D. (2003). Are aftershocks of large Californian earthquakes diffusing? Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 108, 2483. doi:10.1029/2003JB002503.

Helmstetter, A., & Sornette, D. (2003). Importance of direct and indirect triggered seismicity in the ETAS model of seismicity. Geophysical Reseach Letters, 30, 1576. doi:10.1029/2003GL017670.

Karakostas, V. G., Papadimitriou, E. E., & Papazachos, C. B. (2004). Properties of the 2003 Lefkada, Ionian Islands, Greece, earthquake seismic sequence and seismicity triggering. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 94, 1976–1981.

Kilb, D., Gomberg, J., & Bodin, P. (2000). Triggering of earthquake aftershocks by dynamic stresses. Nature, 408, 570–574. doi:10.1038/35046046.

Marsan, D. (2003). Triggering of seismicity at short timescales following Californian earthquakes. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 108, 2266. doi:10.1029/2002JB001946.

Marsan, D., Helmstetter, A., Bouchon, M., & Dublanchet, P. (2014). Foreshock activity related to enhanced aftershock production. Geophysical Research Letters, 41, 2014GL061219. doi:10.1002/2014GL061219.

Marsan, D., & Nalbant, S. S. (2005). Methods for measuring seismicity rate changes: a review and a study of how the M w 7.3 landers earthquake affected the aftershock sequence of the M w 6.1 Joshua Tree earthquake. Pure and Applied Geophysics, 162, 1151–1185. doi:10.1007/s00024-004-2665-4.

Matthews, M. V., & Reasenberg, P. A. (1988). Statistical methods for investigating quiescence and other temporal seismicity patterns. Pure and Applied Geophysics, 126, 357–372. doi:10.1007/BF00879003.

Mignan, A. (2014). The debate on the prognostic value of earthquake foreshocks: A meta-analysis. Scientific Reports. doi:10.1038/srep04099.

Ogata, Y. (1999). Seismicity analysis through point-process modeling: A review. Pure and Applied Geophysics, 155, 471–507. doi:10.1007/s000240050275.

Ogata, Y., & Katsura, K. (2014). Comparing foreshock characteristics and foreshock forecasting in observed and simulated earthquake catalogs. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 119, 2014JB011250. doi:10.1002/2014JB011250.

Ogata, Y., Utsu, T., & Katsura, K. (1995). Statistical features of foreshocks in comparison with other earthquake clusters. Geophysical Journal International, 121, 233–254. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.1995.tb03524.x.

Orfanogiannaki, K., & Papadopoulos, G. A. (2004). Seismicity criteria for the real-time identification of foreshoks in the Corinth Gulf. Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece, 36, 1451–1456.

Papadopoulos, G. A., Drakatos, G., & Plessa, A. (2000). Foreshock activity as a precursor of strong earthquakes in Corinthos Gulf, Central Greece. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth Part: Solid Earth Geodesy, 25, 239–245. doi:10.1016/S1464-1895(00)00039-9.

Papadopoulos, G. A., Latoussakis, I., Daskalaki, E., Diakogianni, G., Fokaefs, A., Kolligri, M., et al. (2006). The East Aegean Sea strong earthquake sequence of October–November 2005: Lessons learned for earthquake prediction from foreshocks. Natural Hazards and Earth Systems Sciences, 6, 895–901.

Papazachos, B. C. (1974). On certain aftershock and foreshock parameters in the area of Greece. Annales Geophysicae, 27, 497–515.

Papazachos, B. C., Tsapanos, T. M., & Panagiotopoulos, D. G. (1982). A premonitory pattern of earthquakes in northern Greece. Nature, 296, 232–235. doi:10.1038/296232a0.

Parsons, T. (2005). A hypothesis for delayed dynamic earthquake triggering. Geophysical Reseach Letters. doi:10.1029/2004GL021811.

Parsons, T., Toda, S., Stein, R. S., Barka, A., & Dieterich, J. H. (2000). Heightened odds of large earthquakes near Istanbul: An interaction-based probability calculation. Science, 288, 661–665. doi:10.1126/science.288.5466.661.

Reasenberg, P. (1985). Second-order moment of central California seismicity, 1969–1982. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 90, 5479–5495. doi:10.1029/JB090iB07p05479.

Stefánsson, R., Böđvarsson, R., Slunga, R., Einarsson, P., Jakobsdóttir, S., Bungum, H., et al. (1993). Earthquake prediction research in the South Iceland seismic zone and the SIL project. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 83, 696–716.

Stein, R. S., Barka, A. A., & Dieterich, J. H. (1997). Progressive failure on the North Anatolian fault since 1939 by earthquake stress triggering. Geophysical Journal International, 128, 594–604. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.1997.tb05321.x.

Toda, S., Stein, R. S., Reasenberg, P. A., Dieterich, J. H., & Yoshida, A. (1998). Stress transferred by the 1995 Mw = 6.9 Kobe, Japan, shock: Effect on aftershocks and future earthquake probabilities. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 103, 24543–24565. doi:10.1029/98JB00765.

Toda, S., Stein, R. S., Richards-Dinger, K., & Bozkurt, S. B. (2005). Forecasting the evolution of seismicity in southern California: Animations built on earthquake stress transfer. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 110, B05S16. doi:10.1029/2004JB003415.

Toda, S., Stein, R. S., & Sagiya, T. (2002). Evidence from the ad 2000 Izu islands earthquake swarm that stressing rate governs seismicity. Nature, 419, 58–61. doi:10.1038/nature00997.

Utsu, T., Ogata, Y., & Matsu’ura, S. R. (1995). The centenary of the Omori formula for a decay law of aftershock activity. Journal of Physics of the Earth, 43, 1–33. doi:10.4294/jpe1952.43.1.

Vere-Jones, D., Ben-Zion, Y., & Zúñiga, R. (2005). Statistical seismology. Pure and Applied Geophysics, 162, 1023–1026. doi:10.1007/s00024-004-2659-2.

Wyss, M., & Stefansson, R. (2006). Nucleation points of recent mainshocks in Southern Iceland, mapped by b-values. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 96, 599–608. doi:10.1785/0120040056.

Wyss, M., & Wiemer, S. (2000). Change in the probability for earthquakes in Southern California due to the Landers magnitude 7.3 earthquake. Science, 290, 1334–1338. doi:10.1126/science.290.5495.1334.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Prof. M. Bouchon and the anonymous reviewer for their comments and suggestions that contributed to bring the article in its present form. Details on the data used in the present study can be found at http://geophysics.geo.auth.gr/ss/station_index_en.html.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Adamaki, A.K., Roberts, R.G. Precursory Activity Before Larger Events in Greece Revealed by Aggregated Seismicity Data. Pure Appl. Geophys. 174, 1331–1343 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-017-1465-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-017-1465-6