Abstract

Background

The issues of replication and scientific transparency have been raised in exercise and sports science research. A potential means to address the replication crisis and enhance research reliability is to improve reporting quality and transparency. This study aims to formulate a reporting checklist as a supplement to the existing reporting guidelines, specifically for resistance exercise studies.

Methods

PubMed (which covers Medline) and Scopus (which covers Medline, EMBASE, Ei Compendex, World Textile Index, Fluidex, Geobase, Biobase, and most journals in Web of Science) were searched for systematic reviews that comprised the primary studies directly comparing different resistance training methods. Basic data on the selected reviews, including on authors, publication years, and objectives, were summarized. The reporting items for the checklist were identified based on the objective of the reviews. Additional items from an existing checklist, namely the Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template, a National Strength and Conditioning Association handbook, and an article from the EQUATOR library were incorporated into the final reporting checklist.

Results

Our database search retrieved 3595 relevant records. After automatic duplicate removal, the titles and abstracts of the remaining 2254 records were screened. The full texts of 137 records were then reviewed, and 88 systematic reviews that met the criteria were included in the umbrella review.

Conclusion

Developed primarily by an umbrella review method, this checklist covers the research questions which have been systematically studied and is expected to improve the reporting completeness of future resistance exercise studies. The PRIRES checklist comprises 26 reporting items (39 subitems) that cover four major topics in resistance exercise intervention: 1) exercise selection, performance, and training parameters, 2) training program and progression, 3) exercise setting, and 4) planned vs actual training. The PRIRES checklist was designed specifically for reporting resistance exercise intervention. It is expected to be used with other reporting guidelines such as Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials and Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials. This article presents only the development process and resulting items of the checklist. An accompanying article detailing the rationale for, the importance of, and examples of each item is being prepared.

Registration

This study is registered with the EQUATOR Network under the title “Preferred Reporting Items for Resistance Exercise Studies (PRIRES).” PROSPERO registration number: CRD42021235259.

Key Points

-

The PRIRES checklist comprises 26 reporting items (39 subitems) that cover four major topics in resistance exercise intervention: 1) exercise selection, performance, and training parameters, 2) training program and progression, 3) exercise setting, and 4) planned vs actual training.

-

The reporting items for the checklist were identified based on the objective of 88 included systematic reviews. Additional items from the Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT), a National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) handbook, and an article from the EQUATOR library, were incorporated into the final reporting checklist.

-

PRIRES checklist is expected to be used with other reporting guidelines such as Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) and Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Resistance training is a potent as well as cost-effective non-pharmaceutical intervention for improving muscular and physical function. Research has shown that muscular strength can be improved by up to 50% in healthy older adults after one year of resistance training [1(R3)]. A recent analysis suggested that resistance training provides the best value for money for fall prevention compared to other unimodal and multimodal interventions [2(C)]. However, though generally beneficial, the effectiveness of resistance training is largely determined by parameters such as training intensity and frequency.

Selecting training parameters according to the training purpose is necessary for achieving optimal results. Although organizations such as the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) have developed some principles for resistance training, e.g., performing ≤ 6 repetitions for maximizing muscle strength gain [3(T15.11)], the influences of many other training parameters, such as optimal time under tension for increasing muscle hypertrophy, require further investigation. However, without complete reporting of the intervention, it is difficult to compare different primary studies and draw conclusions about preferred resistance training methods.

The issues of replication and scientific transparency have been raised in many research fields including psychology [4(T1)], social science [5(Pg638)], and medicine [6,7,8]. Potential means to address the replication crisis and enhance research reliability include trial registration [9(Sec3.2)], publishing the protocol before data collection, the registered reports [9 (Sec. 3.3), 10], a results-free peer review [11, 8, 12], conducting replication studies [4,5,6], and improving transparency [7, 13].

Although the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) [13, 14] and Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT) [15] have been published to enhance the reporting quality of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and exercise interventional studies, respectively, a supplementary preferred reporting checklist can further improve the reporting quality of resistance exercise studies. For instance, there were concerns regarding the reported resistance exercise method and program in 7 of the 11 studies summarized in our previous study [16(I3, T1)]. Specifically, of these 7 studies, three failed to report basic items related to resistance exercise, i.e., repetition, intensity, and rest intervals. In addition, some items regarding the resistance exercise such as the rest interval between sets and exercises and the order of exercises, which had been reported in our previous study [16, 13, 14] and CERT [15] checklists. Thus, a supplementary reporting checklist for resistance exercise studies can be beneficial to future research.

To overcome the limitations of the Delphi technique, which has been used to develop existing reporting checklists such as CONSORT [17(M)], an umbrella review was applied in this study. The Delphi technique was first proposed by Norman Dalkey and Olaf Helmer in the 1950s to develop consensus among experts [18(I3)]. Although it can provide some information, it suffers from several methodological disadvantages that can be avoided using the newer umbrella review technique. An umbrella review is a tertiary research design (in contrast to primary research such as RCTs and secondary research such as systematic reviews) [19(Pg5-6)] that emerged at the beginning of the twenty-first century. This design enables systematic data collection and synthesis on a broad issue, which is impractical for a traditional systematic review. The following are several major comparisons between these two research methods that are of consequence to our study. First, expert opinions in the Delphi technique are ranked the lowest in the evidence hierarchy, as opposed to the umbrella review which is considered the highest [19(F2.1)]. Second, concerns have been raised that the Delphi technique is not fully “systematic.” For instance, Humphrey-Murto and de Wit criticized the Delphi method for the ambiguity of its methodology, poor reporting quality, and the presence of little to no empirical evidence to support best practices in the consensus development stages [20(Pg136)]. Third, regarding the advantages of the proposed checklist, as a supplement to CONSORT, it will need to be updated regularly and in timely fasion for it to function optimally. The feasibility of rapidly developing and updating an umbrella review will be an advantage over the time-consuming Delphi technique. A detailed discussion of the pros and cons of the Delphi technique is beyond the scope of this protocol. An integrative introduction to the umbrella review has been edited by Biondi-Zoccai [19]. The limitations of the Delphi technique in methodology, process, results, and conclusion have been reviewed by Vernon [21], and the disadvantages of this technique, including researcher bias and shortcomings, unethical behavior caused by anonymity, and debates over the method rather than the topic, have been discussed by Avella [22].

After the search, we recognized that an article by Coratella [23], also published in Sports Medicine Open, shared a similar purpose to the PRIRES project. However, there were some differences between these two works. Coratella provided a checklist focusing on within-exercise variables [23], instead of a checklist for the entire resistance training program, and provided his valuable insight in a narrative review format. In contrast, we aimed to develop a checklist for the entire resistance training program with an umbrella review method and therefore preregistered this project with both EQUATOR in 2020 and PROSPERO in 2021. We believe that the PRIRES can broade in 2021. We believe that the PRIRES can broaden the scope of Coratella’s checklist. Even if some reporting suggestions might overlap conceptually between PRIRES and the article by Coratella, the methodological processing in generating these recommendations differed substantially.

There are two major differences in research methods between PRIRES and the excellent work by Coratella [23]. First, the research purposes are not the same. Coratella provided his insight and reporting recommendations (8 reporting items) focusing on the “within-exercise” variable, while PRIRES is a project for developing a complete checklist for resistance training interventions including between-exercise variables, training progress, and unconventional training methods (e.g., blood flow restriction).

The second major difference is the methodological approach to constructing the checklist. Although the PRIRES is not free from the authors’ subjective perspective (e.g., item 4c “relative intensity” was retrieved from the NSCA handbook based on our knowledge), a significant amount of effort was made to ensure this checklist was as objective as possible by developing the item extraction protocol, and as inclusive as possible by conducting a systematic search in two databases. The umbrella review and the narrative review are both important research formats and the reporting recommendations derived from these two different methods, even if they are similar conceptually, have their own merits.

This study aims to construct a reporting checklist as a supplement to the existing reporting guidelines such as CONSORT [13, 14], specifically for resistance exercise studies. A preferred reporting items checklist developed using umbrella review methods promises to be more systematic and provides a higher level of evidence than those developed using the Delphi technique. In order to show how the research question developed, the original objective and rationale, which were written before the results were known, are provided in Additional file 1: Original Rationale and Objective.

Methods

This study was reported according to the reporting checklist for umbrella reviews published by Onishi and Furukawa in 2016 [24(T13.1)]; see Additional file 2: Umbrella Review Reporting Checklist.

Inclusion Criteria

-

1.

Systematic reviews that comprised primary studies directly comparing different resistance training methods.

-

2.

Resistance exercise was the primary intervention.

-

3.

There were no limitations on the characteristics of the participants recruited.

Exclusion Criteria

-

1.

Systematic reviews that involved other types of exercise, such as concurrent training (aerobic + resistance exercises), or other interventions (e.g., diet and supplements).

-

2.

Reviews not published in full and/or not published in English.

-

3.

Reviews that included animal studies.

-

4.

Reviews that included studies of resistance training targeting respiratory or oral muscles.

Search Strategies and Information Sources

Systematic reviews that investigate the effects of different resistance exercise parameters, such as the types of resistance exercise and training frequency, were identified by searching PubMed (covers Medline) and Scopus (covers Medline, EMBASE, Compendex, World Textile Index, Fluidex, Geobase, and Biobase [25(T1)] and most journals in Web of Science [26(F2)]) using the following keywords:

“resistance exercise*” or “resistance train*” or “weight exercise*” or “weight train*” or “weight bear*” or “weight-bear*” “weightlift” or “weight lift*” or “strength train*” or “strength exercise*” or “power train*” or “power exercise” or “explosive exercise*” (in Title/Abstract).

AND

Systematic or meta (in Title).

The search syntax is outlined in Additional file 3: Syntax of Literature Search.

Data Selection and Collection Process

The titles and abstracts retrieved from different databases were loaded into Endnote 20 to remove duplicates automatically. The authors TYL and TYC independently screened all titles and abstracts against the selection criteria. The full-text screening was performed if the titles and abstracts indicated that the studies met the criteria or if there was any uncertainty. Multiple reports were checked by searching the first author’s name in Endnote 20 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and the registration ID. If multiple reports were found, the most detailed one was included. If disagreements could not be resolved via discussion, the author TMH was consulted.

Reporting Items

Basic data on the included systematic reviews, including authors, publication years, and objectives, were extracted and tabulated. The reporting items were identified based on the objectives of the reviews. Additional information was sought from relevant published guidelines such as the CERT [15] from the EQUATOR library to build this reporting checklist for resistance exercise studies. The quality of the systematic reviews was not judged because this was beyond the scope of this umbrella review.

Results

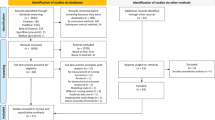

Our database search retrieved 3,595 relevant records (May 5, 2022). After automatic duplicate removal by EndNote 20, the titles and abstracts of the remaining 2,254 records were manually screened by the authors TYL and TYC independently. One hundred and thirty-seven articles were successfully retrieved and their full texts were screened by TYL. Finally, 88 studies were included in the review; see Fig. 1 for the modified PRISMA 2020 flow diagram.

The 49 records excluded after the full-text review and the reasons for their exclusion are listed in Additional file 4: Records Excluded After the Full-Text Review and summarized in Fig. 1. The most common reason for exclusion was that the reviews included studies that did not directly compare different resistance training methods or included non-resistance exercise interventions (n = 44).

Table 1 shows all 26 reporting items (39 subitems) extracted. Twenty items (30 subitems) were identified from the included systematic reviews based on their research objectives (see Additional file 5: Included Reviews and Research Questions); six items (seven subitems) were adapted from the CERT reporting checklist; one subitem was retrieved from an article in the EQUATOR library, which aimed to clearly define a set endpoint in resistance exercise [27(T3)], and one subitem was identified from a National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) handbook [3(T15.17)].

Discussion

The Preferred Reporting Items for Resistance Exercise Studies (PRIRES) checklist comprises 26 reporting items that cover four major topics of research on resistance exercise training: 1) exercise selection, performance, and training parameters, 2) training program and progression, 3) exercise setting, and 4) planned vs actual training.

The first section of this reporting checklist, exercise selection, performance, and training parameters, covers the content and flow of a given resistance exercise session. The second section, training program and progression, covers the rules and decisions related to the training progression and to the methods specific to resistance training, such as velocity-based training and periodization. The third section of the checklist, exercise setting, reminds users to report the environment in which the resistance exercise was conducted. Planned vs actual training, the fourth section, points out that researchers should provide information about how well the participants were able to adhere to the intervention plan and about unintended deviations that occurred.

Two subitems of the PRIRES checklist, namely those relating to relative intensity (Item 4c) and set endpoint (Item 5c), were neither identified from the included systematic reviews nor adapted from the CERT checklist. Retrieved from an NSCA handbook [3] (T15.17), Item 4c addresses relative training intensity, which, unlike absolute training intensity, reflects not only the absolute load but also the number of repetitions in a set. Therefore, it can more accurately indicate how difficult a given set is. Item 5c, set endpoint, is adapted from an article by Steele et al. [27]. In this article, they showed the ambiguity in the use and definition of the set endpoint [27(Pg368-370)] and provided recommendations [27(T3)] on how to report it. Both relative intensity and a clearly defined set endpoint are essential measures for comparing resistance exercise studies.

The PRIRES checklist was designed specifically for reporting resistance exercise interventions and is expected to be used with other reporting guidelines. For example, for a resistance training RCT, PRIRES can be used with CONSORT [28] which covers the overall design of a trial, such as the randomization process and masking (i.e., blinding). PRIRES can also be applied to an interventional study protocol and used with the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) [29]. The editable checklists for both completed studies and protocol are provided in Additional files 6 and 7.

The article published in 2022 by Coratella [23] provided a comprehensive view of how training variables beyond load and number of repetitions influence training stimuli. For instance, Coratella explained that even when the load, number of repetitions, and displacement per repetition are fixed, the differences in muscle length being trained can affect acute as well as long-term results [23 (PP. 4–5)]. Moreover, Coratella also provided in-depth coverage of the influences of manipulations of these training variables on muscle strength and hypertrophy. In the PRIRES checklist, we address the training volume issue by listing the volume-related variables individually instead of labeling a single “training volume” item and consider the examination of the training effect of reporting items as out of scope when developing a checklist. Investigating the training effect of these items in a future umbrella review is expected to be valuable [30].

This article presents the development process and resulting items of the PRIRES checklist but not why each item is critical and relevant. Motivated by the CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration [31], we are preparing an accompanying article [32], which will describe the rationale, importance, and examples regarding each item.

In-text citation: This article follows the more precise citation method [33]. In-text citation: I: introduction; M: method; R: results; D: discussion; C: conclusion; the number after abbreviation: paragraph (para.); T: table; F: figure; Sec: section; Pg: page.

Registration

This study is registered with the EQUATOR Network and is available at https://www.equator-network.org/library/reporting-guidelines-under-development/reporting-guidelines-under-development-for-clinical-trials/#PRIRES. The protocol is registered with PROSPERO (CRD42021235259).

Conclusions

The PRIRES checklist was developed primarily via carrying out an umbrella review of systematic reviews and adapting the existing CERT checklist. This development process allowed PRIRES to address the research questions that have been systematically studied. The checklist is expected to improve the reporting completeness of future resistance exercise studies.

Availability of Data and Materials

All available data were presented in this manuscript and supplementary information.

Abbreviations

- PRIRES:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Resistance Exercise Studies

- EQUATOR:

-

Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research

- PROSPERO:

-

International prospective register of systematic reviews

- CERT:

-

Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template

- NSCA:

-

National Strength and Conditioning Association

- CONSORT:

-

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- SPIRIT:

-

Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

References

Rhodes EC, Martin AD, Taunton JE, Donnelly M, Warren J, Elliot J. Effects of one year of resistance training on the relation between muscular strength and bone density in elderly women. Br J Sports Med. 2000;34(1):18–22.

Adjetey C, Karnon B, Falck RS, Balasubramaniam H, Buschert K, Davis JC. Cost-effectiveness of exercise versus multimodal interventions that include exercise to prevent falls among community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas. 2023;169:16–31.

Haff GG, Haff EE. Resistance training program design. In: Coburn JW, Malek MH, editors. NSCA's essentials of personal training: human kinetics;2011.

Open Science Collaboration. PSYCHOLOGY. Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science. 2015;349(6251):aac4716.

Camerer CF, Dreber A, Holzmeister F, Ho T-H, Huber J, Johannesson M, et al. Evaluating the replicability of social science experiments in Nature and Science between 2010 and 2015. Nat Hum Behav. 2018;2(9):637–44.

Errington TM, Mathur M, Soderberg CK, Denis A, Perfito N, Iorns E, et al. Investigating the replicability of preclinical cancer biology. eLife. 2021;10:e71601.

Halperin I, Vigotsky AD, Foster C, Pyne DB. Strengthening the practice of exercise and sport-science research. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2018;13(2):127–34.

Schweizer G, Furley P. Reproducible research in sport and exercise psychology: the role of sample sizes. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2016;23:114–22.

Caldwell AR, Vigotsky AD, Tenan MS, Radel R, Mellor DT, Kreutzer A, et al. Moving sport and exercise science forward: a call for the adoption of more transparent research practices. Sports Med 2020;50(3):449–59.

Law LS-C, Lo EA-G. A two-stage review process for randomized controlled trials: the ultimate solution for publication bias? Can J Anesthesia 2016;63(12):1381–2.

Button KS, Bal L, Clark A, Shipley T. Preventing the ends from justifying the means: withholding results to address publication bias in peer-review. BMC Psychol 2016;4(1):59.

Button KS, Ioannidis JPA, Mokrysz C, Nosek BA, Flint J, Robinson ESJ, et al. Power failure: why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2013;14(5):365–76.

Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gøtzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340: c869.

Dwan K, Li T, Altman DG, Elbourne D. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised crossover trials. BMJ. 2019;366: l4378.

Slade SC, Dionne CE, Underwood M, Buchbinder R. Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT): explanation and elaboration statement. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(23):1428–37.

Lin T-Y, Hsieh S-S, Chueh T-Y, Huang C-J, Hung T-M. The effects of barbell resistance exercise on information processing speed and conflict-related ERP in older adults: a crossover randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 2021;11(1):9137.

Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, Horton R, Moher D, Olkin I, et al. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA. 1996;276(8):637–9.

Barrett D, Heale R. What are Delphi studies? Evid Based Nurs. 2020;23(3):68–9.

Biondi-Zoccai G. Umbrella reviews: evidence synthesis with overviews of reviews and meta-epidemiologic studies: Springer; 2016.

Humphrey-Murto S, de Wit M. The Delphi method-more research please. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;106:136–9.

Vernon W. The Delphi technique: a review. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2009;16(2):69–76.

Avella J. Delphi panels: research design, procedures, advantages, and challenges. Int J Doctoral Stud. 2016;11:305–21.

Coratella G. Appropriate reporting of exercise variables in resistance training protocols: much more than load and number of repetitions. Sports Med Open. 2022;8(1):99.

Onishi A, Furukawa TA. State-of-the-art reporting. Umbrella reviews. Berlin: Springer; 2016. p. 189–202.

Falagas ME, Pitsouni EI, Malietzis GA, Pappas G. Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: strengths and weaknesses. FASEB J. 2008;22(2):338–42.

Mongeon P, Paul-Hus A. The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: a comparative analysis. Scientometrics. 2016;106(1):213–28.

Steele J, Fisher J, Giessing J, Gentil P. Clarity in reporting terminology and definitions of set endpoints in resistance training. Muscle Nerve. 2017;56(3):368–74.

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, Group C. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Trials. 2010;11(1):32.

Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, Altman DG, Mann H, Berlin JA, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ Br Med J. 2013;346: e7586.

Ting-Yu Lin T-YCT-MH. Preferred resistance training methods (PRTM): an umbrella review of systematic reviews [CRD42023411498]. 2023 (PROSPERO registration).

Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gøtzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. International Journal of Surgery. 2012;10(1):28–55.

Lin T-Y, Chueh T-Y, Hung T-M. Preferred Reporting Items for Resistance Exercise Studies (PRIRES): Explanation and Elaboration (in preparation).

Lin T-Y, Hung T-M. How to reduce errors and improve transparency by using more precise citations. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9.

Kassiano W, Nunes JP, Costa B, Ribeiro AS, Schoenfeld BJ, Cyrino ES. Does varying resistance exercises promote superior muscle hypertrophy and strength gains? A systematic review. J Strength Cond Res. 2022.

Heidel KA, Novak ZJ, Dankel SJ. Machines and free weight exercises: a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing changes in muscle size, strength, and power. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2021.

Moran J, Ramirez-Campillo R, Liew B, Chaabene H, Behm DG, García-Hermoso A, et al. Effects of bilateral and unilateral resistance training on horizontally orientated movement performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2021;51(2):225–42.

Schoenfeld BJ, Grgic J. Effects of range of motion on muscle development during resistance training interventions: a systematic review. SAGE Open Med. 2020;8:2050312120901559.

Pallarés JG, Hernández-Belmonte A, Martínez-Cava A, Vetrovsky T, Steffl M, Courel-Ibáñez J. Effects of range of motion on resistance training adaptations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2021;31(10):1866–81.

Schoenfeld BJ, Ogborn D, Krieger JW. Effects of resistance training frequency on measures of muscle hypertrophy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2016;46(11):1689–97.

Ralston GW, Kilgore L, Wyatt FB, Baker JS. The effect of weekly set volume on strength gain: a meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2017;47(12):2585–601.

Schoenfeld BJ, Ogborn D, Krieger JW. Dose-response relationship between weekly resistance training volume and increases in muscle mass: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sports Sci. 2017;35(11):1073–82.

Grgic J, Schoenfeld BJ, Davies TB, Lazinica B, Krieger JW, Pedisic Z. Effect of resistance training frequency on gains in muscular strength: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2018;48(5):1207–20.

Ralston GW, Kilgore L, Wyatt FB, Buchan D, Baker JS. Weekly training frequency effects on strength gain: a meta-analysis. Sports Med Open. 2018;4(1).

Schoenfeld BJ, Grgic J, Krieger J. How many times per week should a muscle be trained to maximize muscle hypertrophy? A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies examining the effects of resistance training frequency. J Sports Sci. 2019;37(11):1286–95.

Androulakis-Korakakis P, Fisher JP, Steele J. The minimum effective training dose required to increase 1RM strength in resistance-trained men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2020;50(4):751–65.

Baz-Valle E, Fontes-Villalba M, Santos-Concejero J. Total number of sets as a training volume quantification method for muscle hypertrophy: a systematic review. J Strength Cond Res. 2021;35(3):870–8.

Cuthbert M, Haff GG, Arent SM, Ripley N, McMahon JJ, Evans M, et al. Effects of variations in resistance training frequency on strength development in well-trained populations and implications for in-season athlete training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2021;51(9):1967–82.

Baz-Valle E, Balsalobre-Fernández C, Alix-Fages C, Santos-Concejero J. A systematic review of the effects of different resistance training volumes on muscle hypertrophy. J Hum Kinet. 2022;81(1):199–210.

Ribeiro B, Pereira A, Neves P, Marinho D, Marques M, Neiva HP. The effect of warm-up in resistance training and strength performance: a systematic review. Motricidade. 2021;17:87–94.

Tschopp M, Sattelmayer MK, Hilfiker R. Is power training or conventional resistance training better for function in elderly persons? A meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2011;40(5):549–56.

Raymond MJ, Bramley-Tzerefos RE, Jeffs KJ, Winter A, Holland AE. Systematic review of high-intensity progressive resistance strength training of the lower limb compared with other intensities of strength training in older adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(8):1458–72.

Csapo R, Alegre LM. Effects of resistance training with moderate vs heavy loads on muscle mass and strength in the elderly: a meta-analysis. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2016;26(9):995–1006.

Schoenfeld BJ, Wilson JM, Lowery RP, Krieger JW. Muscular adaptations in low- versus high-load resistance training: a meta-analysis. Eur J Sport Sci. 2016;16(1):1–10.

Schoenfeld BJ, Grgic J, Ogborn D, Krieger JW. Strength and hypertrophy adaptations between low- vs. high-load resistance training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Strength Cond Res. 2017;31(12):3508–23.

Hansen D, Abreu A, Doherty P, Völler H. Dynamic strength training intensity in cardiovascular rehabilitation: Is it time to reconsider clinical practice? A systematic review. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019;26(14):1483–92.

Grgic J. The effects of low-load vs. high-load resistance training on muscle fiber hypertrophy: a meta-analysis. J Hum Kinet. 2020;74(1):51–8.

João GA, Rodriguez D, Tavares LD, Carvas Junior N, Miranda ML, Reis VM, et al. Can intensity in strength training change caloric expenditure? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2020;40(2):55–66.

Souza D, Barbalho M, Ramirez-Campillo R, Martins W, Gentil P. High and low-load resistance training produce similar effects on bone mineral density of middle-aged and older people: a systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Exp Gerontol. 2020;138.

Lacio M, Vieira JG, Trybulski R, Campos Y, Santana D, Filho JE, et al. Effects of resistance training performed with different loads in untrained and trained male adult individuals on maximal strength and muscle hypertrophy: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(21).

Lopez P, Radaelli R, Taaffe DR, Newton RU, Galvão DA, Trajano GS, et al. Resistance training load effects on muscle hypertrophy and strength gain: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2021;53(6):1206–16.

Refalo MC, Hamilton DL, Paval DR, Gallagher IJ, Feros SA, Fyfe JJ. Influence of resistance training load on measures of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and improvements in maximal strength and neuromuscular task performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sports Sci. 2021;39(15):1723–45.

Carvalho L, Junior RM, Barreira J, Schoenfeld BJ, Orazem J, Barroso R. Muscle hypertrophy and strength gains after resistance training with different volume-matched loads: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2022;47(4):357–68.

Zhang X, Li H, Bi S, Luo Y, Cao Y, Zhang G. Auto-regulation method vs. fixed-loading method in maximum strength training for athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Physiol. 2021;12.

Hickmott LM, Chilibeck PD, Shaw KA, Butcher SJ. The effect of load and volume autoregulation on muscular strength and hypertrophy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med Open. 2022;8(1).

Hackett DA, Ghayomzadeh M, Farrell SN, Davies TB, Sabag A. Influence of total repetitions per set on local muscular endurance: a systematic review with meta-analysis and meta-regression. Sci Sports. 2022.

Davies T, Orr R, Halaki M, Hackett D. Effect of training leading to repetition failure on muscular strength: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2016;46(4):487–502.

Cerqueira MS, Maciel DG, Barboza JAM, Centner C, Lira M, Pereira R, et al. Effects of low-load blood flow restriction exercise to failure and non-failure on myoelectric activity: a meta-analysis. J Athl Train. 2021;57(4):402–17.

Vieira AF, Umpierre D, Teodoro JL, Lisboa SC, Baroni BM, Izquierdo M, et al. Effects of resistance training performed to failure or not to failure on muscle strength, hypertrophy, and power output: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Strength Cond Res. 2021;35(4):1165–75.

Grgic J, Schoenfeld BJ, Orazem J, Sabol F. Effects of resistance training performed to repetition failure or non-failure on muscular strength and hypertrophy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sport Health Sci. 2022;11(2):202–11.

Vieira JG, Sardeli AV, Dias MR, Filho JE, Campos Y, Sant’Ana L, et al. Effects of resistance training to muscle failure on acute fatigue: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2022;52(5):1103–25.

Krzysztofik M, Wilk M, Wojdała G, Gołaś A. Maximizing muscle hypertrophy: a systematic review of advanced resistance training techniques and methods. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(24).

Nunes JP, Grgic J, Cunha PM, Ribeiro AS, Schoenfeld BJ, de Salles BF, et al. What influence does resistance exercise order have on muscular strength gains and muscle hypertrophy? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Sport Sci. 2021;21(2):149–57.

Latella C, Teo WP, Drinkwater EJ, Kendall K, Haff GG. The acute neuromuscular responses to cluster set resistance training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2019;49(12):1861–77.

Jukic I, Ramos AG, Helms ER, McGuigan MR, Tufano JJ. Acute effects of cluster and rest redistribution set structures on mechanical, metabolic, and perceptual fatigue during and after resistance training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2020;50(12):2209–36.

Davies TB, Tran DL, Hogan CM, Haff GG, Latella C. Chronic Effects of altering resistance training set configurations using cluster sets: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2021;51(4):707–36.

Jukic I, Van Hooren B, Ramos AG, Helms ER, McGuigan MR, Tufano JJ. The effects of set structure manipulation on chronic adaptations to resistance training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2021;51(5):1061–86.

Durall CJ, Hermsen D, Demuth C. Systematic review of single-set versus multiple-set resistance-training randomized controlled trials: Implications for rehabilitation. Crit Rev Phys Rehabil Med. 2006;18(2):107–16.

Bågenhammar S, Hansson EE. Repeated sets or single set of resistance training—a systematic review. Adv Physiother. 2007;9(4):154–60.

Krieger JW. Single versus multiple sets of resistance exercise: a Meta-regression. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23(6):1890–901.

Krieger JW. Single vs. multiple sets of resistance exercise for muscle hypertrophy: a meta-analysis. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(4):1150–9.

Ralston GW, Kilgore L, Wyatt FB, Dutheil F, Jaekel P, Buchan DS, et al. Re-examination of 1- vs. 3-sets of resistance exercise for pre-spaceflight muscle conditioning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Physiol. 2019;10:864.

Grgic J, Lazinica B, Mikulic P, Krieger JW, Schoenfeld BJ. The effects of short versus long inter-set rest intervals in resistance training on measures of muscle hypertrophy: a systematic review. Eur J Sport Sci. 2017;17(8):983–93.

Grgic J, Schoenfeld BJ, Skrepnik M, Davies TB, Mikulic P. Effects of rest interval duration in resistance training on measures of muscular strength: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2018;48(1):137–51.

da Silva JB, de Lima e Silva L, Nunes RAM, Lopes GC, de Mello DB, Lima VP, et al. Evaluation methods and objectives for neuromuscular and hemodynamic responses subsequent to different rest intervals in resistance training: a systematic review. Arch Med Deporte. 2021;38(3):180–4.

Schoenfeld BJ, Ogborn DI, Krieger JW. Effect of repetition duration during resistance training on muscle hypertrophy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2015;45(4):577–85.

Davies TB, Kuang K, Orr R, Halaki M, Hackett D. Effect of movement velocity during resistance training on dynamic muscular strength: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2017;47(8):1603–17.

Hackett DA, Davies TB, Orr R, Kuang K, Halaki M. Effect of movement velocity during resistance training on muscle-specific hypertrophy: a systematic review. Eur J Sport Sci. 2018;18(4):473–82.

da Rosa Orssatto LB, de la Rocha Freitas C, Shield AJ, Silveira Pinto R, Trajano GS. Effects of resistance training concentric velocity on older adults' functional capacity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Exp Gerontol. 2019;127.

Larsen S, Kristiansen E, van den Tillaar R. Effects of subjective and objective autoregulation methods for intensity and volume on enhancing maximal strength during resistance-training interventions: a systematic review. PeerJ. 2021;9.

Liao KF, Wang XX, Han MY, Li LL, Nassis GP, Li YM. Effects of velocity based training vs. traditional 1RM percentage-based training on improving strength, jump, linear sprint and change of direction speed performance: a systematic review with meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(11 November).

Orange ST, Hritz A, Pearson L, Jeffries O, Jones TW, Steele J. Comparison of the effects of velocity-based vs. traditional resistance training methods on adaptations in strength, power, and sprint speed: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and quality of evidence appraisal. J Sports Sci. 2022;1–15.

Zhang M, Tan Q, Sun J, Ding S, Yang Q, Zhang Z, et al. Comparison of velocity and percentage-based training on maximal strength: meta-analysis. Int J Sports Med. 2022.

Grgic J, Mikulic I, Mikulic P. Acute and long-term effects of attentional focus strategies on muscular strength: a meta-analysis. Sports. 2021;9(11).

Grgic J, Mikulic P. Effects of attentional focus on muscular endurance: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;19(1).

Roig M, O’Brien K, Kirk G, Murray R, McKinnon P, Shadgan B, et al. The effects of eccentric versus concentric resistance training on muscle strength and mass in healthy adults: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(8):556–68.

Douglas J, Pearson S, Ross A, McGuigan M. Chronic adaptations to eccentric training: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2017;47(5):917–41.

Schoenfeld BJ, Ogborn DI, Vigotsky AD, Franchi MV, Krieger JW. Hypertrophic effects of concentric vs. eccentric muscle actions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Strength Cond Res. 2017;31(9):2599–608.

Molinari T, Steffens T, Roncada C, Rodrigues R, Dias CP. Effects of eccentric-focused versus conventional training on lower limb muscular strength in older adults: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Aging Phys Act. 2019;27(6):823–30.

Buskard ANL, Gregg HR, Ahn S. Supramaximal eccentrics versus traditional loading in improving lower-body 1RM: a meta-analysis. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2018;89(3):340–6.

Latella C, Grgic J, Der Westhuizen DV. Effect of interset strategies on acute resistance training performance and physiological responses: a systematic review. J Strength Cond Res. 2019;33:S180–93.

Harries SK, Lubans DR, Callister R. Systematic review and meta-analysis of linear and undulating periodized resistance training programs on muscular strength. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29(4):1113–25.

Grgic J, Mikulic P, Podnar H, Pedisic Z. Effects of linear and daily undulating periodized resistance training programs on measures of muscle hypertrophy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ. 2017;2017(8).

Williams TD, Tolusso DV, Fedewa MV, Esco MR. Comparison of periodized and non-periodized resistance training on maximal strength: a meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2017;47(10):2083–100.

Grgic J, Lazinica B, Mikulic P, Schoenfeld BJ. Should resistance training programs aimed at muscular hypertrophy be periodized? A systematic review of periodized versus non-periodized approaches. Sci Sports. 2018;33(3):e97–104.

Moesgaard L, Beck MM, Christiansen L, Aagaard P, Lundbye-Jensen J. Effects of periodization on strength and muscle hypertrophy in volume-equated resistance training programs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2022.

Grgic J, Lazinica B, Garofolini A, Schoenfeld BJ, Saner NJ, Mikulic P. The effects of time of day-specific resistance training on adaptations in skeletal muscle hypertrophy and muscle strength: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chronobiol Int. 2019;36(4):449–60.

Domingos E, Polito MD. Blood pressure response between resistance exercise with and without blood flow restriction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Life Sci. 2018;209:122–31.

Lixandrão ME, Ugrinowitsch C, Berton R, Vechin FC, Conceição MS, Damas F, et al. Magnitude of muscle strength and mass adaptations between high-load resistance training versus low-load resistance training associated with blood-flow restriction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2018;48(2):361–78.

Centner C, Lauber B. A Systematic review and meta-analysis on neural adaptations following blood flow restriction training: what we know and what we don’t know. Front Physiol. 2020;11:887.

Cuyul-Vásquez I, Leiva-Sepúlveda A, Catalán-Medalla O, Araya-Quintanilla F, Gutiérrez-Espinoza H. The addition of blood flow restriction to resistance exercise in individuals with knee pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz J Phys Ther. 2020.

Ferlito JV, Pecce SAP, Oselame L, De Marchi T. The blood flow restriction training effect in knee osteoarthritis people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2020;34(11):1378–90.

Grønfeldt BM, Lindberg Nielsen J, Mieritz RM, Lund H, Aagaard P. Effect of blood-flow restricted vs heavy-load strength training on muscle strength: systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2020;30(5):837–48.

Cerqueira MS, Lira M, Mendonça Barboza JA, Burr JF, Wanderley ELTB, Maciel DG, et al. Repetition failure occurs earlier during low-load resistance exercise with high but not low blood flow restriction pressures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Strength Cond Res. 2021 Jul 26.

de Queiros VS, de França IM, Trybulski R, Vieira JG, dos Santos IK, Neto GR, et al. Myoelectric activity and fatigue in low-load resistance exercise with different pressure of blood flow restriction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Physiol. 2021;12.

Liu Y, Jiang N, Pang F, Chen T. Resistance training with blood flow restriction on vascular function: a meta-analysis. Int J Sports Med. 2021;42(7):577–87.

Nitzsche N, Stäuber A, Tiede S, Schulz H. The effectiveness of blood-flow restricted resistance training in the musculoskeletal rehabilitation of patients with lower limb disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2021;35(9):1221–34.

Rodrigo-Mallorca D, Loaiza-Betancur AF, Monteagudo P, Blasco-Lafarga C, Chulvi-Medrano I. Resistance training with blood flow restriction compared to traditional resistance training on strength and muscle mass in non-active older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(21).

Koc BB, Truyens A, Heymans MJLF, Jansen EJP, Schotanus MGM. Effect of low-load blood flow restriction training after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. Int J Sport Phys Ther. 2022;17(3):334–46.

Lopes JSS, Machado AF, Micheletti JK, de Almeida AC, Cavina AP, Pastre CM. Effects of training with elastic resistance versus conventional resistance on muscular strength: a systematic review and meta-analysis. SAGE Open Med. 2019;7:2050312119831116.

Vicens-Bordas J, Esteve E, Fort-Vanmeerhaeghe A, Bandholm T, Thorborg K. Is inertial flywheel resistance training superior to gravity-dependent resistance training in improving muscle strength? A systematic review with meta-analyses. J Sci Med Sport. 2018;21(1):75–83.

Ramos-Campo DJ, Scott BR, Alcaraz PE, Rubio-Arias JA. The efficacy of resistance training in hypoxia to enhance strength and muscle growth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Sport Sci. 2018;18(1):92–103.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

TYL is supported by the Scholarship Program for Elite Doctoral Students [Ministry of Science and Technology (Taiwan)]. The funder played no role in this protocol and did not influence the implementation or publication of this research project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TYL (lead author) conceived and designed the protocol of this study and is the guarantor for the study and person responsible for writing initial draft. TYC was responsible for study design and provided suggestions regarding the literature search strategy and the method. TMH was the adviser when there was any disagreement between the first two authors that could not be solved by discussion and was responsible for reviewing the final manuscript. All authors contributed to drafting the protocol and approving the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

. Original Rationale and Objective.

Additional file 2

. Umbrella Review Reporting Checklist.

Additional file 3

. Syntax of Literature Search.

Additional file 4

. Records Excluded After the Full-Text Review.

Additional file 5

. Included Reviews and Research Questions.

Additional file 6

. Preferred Reporting Items for Resistance Exercise Studies (PRIRES) Checklist for Completed Studies.

Additional file 7

. Preferred Reporting Items for Resistance Exercise Studies (PRIRES) Checklist for Protocols.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, TY., Chueh, TY. & Hung, TM. Preferred Reporting Items for Resistance Exercise Studies (PRIRES): A Checklist Developed Using an Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews. Sports Med - Open 9, 114 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-023-00640-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-023-00640-1