Abstract

Background

To find semi-quantitative and quantitative Positron Emission Tomography/Magnetic Resonance (PET/MR) imaging metrics of both tumor and non-malignant lymphoid tissue (bone marrow and spleen) for Progression Free Survival (PFS) and Overall Survival (OS) prediction in patients with relapsed/refractory (r/r) large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) undergoing Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.

Methods

A single-center prospective study of 16 r/r LBCL patients undergoing CD19-targeted CAR T-cell therapy. Whole body 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET/MR imaging pre-therapy and 3 weeks post-therapy were followed by manual segmentation of tumors and lymphoid tissues. Semi-quantitative and quantitative metrics were extracted, and the metric-wise rate of change (Δ) between post-therapy and pre-therapy calculated. Tumor metrics included maximum Standardized Uptake Value (SUVmax), mean SUV (SUVmean), Metabolic Tumor Volume (MTV), Tumor Lesion Glycolysis (TLG), structural volume (V), total structural tumor burden (Vtotal) and mean Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADCmean). For lymphoid tissues, metrics extracted were SUVmean, mean Fat Fraction (FFmean) and ADCmean for bone marrow, and SUVmean, V and ADCmean for spleen. Univariate Cox regression analysis tested the relationship between extracted metrics and PFS and OS. Survival curves were produced using Kaplan–Meier analysis and compared using the log-rank test, with the median used for dichotomization. Uncorrected p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Correction for multiple comparisons was performed, with a False Discovery Rate (FDR) < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Pre-therapy (p < 0.05, FDR < 0.05) and Δ (p < 0.05, FDR > 0.05) total tumor burden structural and metabolic metrics were associated with PFS and/or OS. According to Kaplan-Meier analysis, a longer PFS was reached for patients with pre-therapy MTV ≤ 39.5 ml, ΔMTV≤1.35 and ΔTLG≤1.35. ΔSUVmax was associated with PFS (p < 0.05, FDR > 0.05), while ΔADCmean was associated with both PFS and OS (p < 0.05, FDR > 0.05). ΔADCmean > 0.92 gave longer PFS and OS in the Kaplan-Meier analysis. Pre-therapy bone marrow SUVmean was associated with PFS (p < 0.05, FDR < 0.05) and OS (p < 0.05, FDR > 0.05). For bone marrow FDG uptake, patient stratification was possible pre-therapy (SUVmean ≤ 1.8).

Conclusions

MTV, tumor ADCmean and FDG uptake in bone marrow unaffected by tumor infiltration are possible PET/MR parameters for prediction of PFS and OS in r/r LBCL treated with CAR T-cells.

Trial registration

EudraCT 2016–004043-36.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

CD19-targeted Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-cells have successfully been used in treatment of relapsed/refractory (r/r) large B-cell lymphomas (LBCL) with three commercially available therapies [1,2,3]. Although complete response rates of 40–59% have been shown in clinical trials [4], the therapy is associated with e.g. life-threatening toxicities, antigen escape and poor tumor infiltration that limit therapeutic efficacy [5]. In addition, a significant cost is currently associated with the treatment. Biomarkers that predict durable response are hence needed, either at baseline to identify patients likely to respond or early post-therapy to detect therapy failure [6].

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography (PET/CT) is a recognized imaging modality for staging and response evaluation in lymphoma for standard chemo- and immunochemo-therapy treatments regimens [7,8,9]. In addition, FDG PET/CT is a promising tool for identifying responding/non-responding patients after CAR T-cell therapy. In patients with LBCL undergoing CAR T-cell therapy, usage of pre-therapy FDG PET tumor metrics such as the Metabolic Tumor Volume (MTV), Total Lesion Glycolysis (TLG) and maximum Standardized Uptake Value (SUVmax) have been associated with treatment outcome [10,11,12,13,14,15]. A lower tumor burden and/or lower tumor FDG uptake have been linked to better outcomes. An early metabolic response after treatment has also proved predictive of therapy success, assessed visually [13, 16] or semi-quantitatively using SUVmax [12, 13, 15]. In general, the studies performed are however small and mixed results have been reported in terms of which predictive metric to use. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, there is no study using FDG PET/MR for CAR T-cell therapy evaluation.

Usage of FDG PET/MR in lymphoma has been shown comparable to FDG PET/CT for diagnosis [17, 18]. In addition to structural imaging, MR can provide functional tumor information without exposure to ionizing radiation. Whole-body Diffusion Weighted Imaging (DWI) [19] and subsequent quantification using the tumor Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) has been described as promising for assessing treatment response in lymphoma [20]. Previous studies of chemo- and immunochemo-therapy in non-Hodgkin lymphoma have shown that an increase in tumor ADC is detectable as early as 1–2 weeks post-therapy [21] and associated with therapy outcome [22,23,24].

In addition to tumor evaluations, the acquisitions of whole body imaging datasets make system wide assessments possible. Of particular interest is imaging of lymphoid tissues, e.g. bone marrow and spleen, as immunological mechanisms could play a role in the efficacy of CAR T-cell therapy [25]. Metabolic changes in lymphoid tissues have been associated with immunotherapy outcome using both PET/CT [26] and PET/MR [27] for checkpoint inhibitor therapy (CIT) in melanoma, but for CAR T-cell therapy less has been reported. Derlin et al. however showed that larger decreases in post-therapeutic FDG PET uptake in normal spleen and lymph nodes were associated with unfavorable CAR T-cell therapy outcome in a small cohort of LBCL patients (n = 7) scanned on PET/CT [28].

The aim of this study was to find semi-quantitative and quantitative PET/MR imaging metrics of both tumor and non-malignant lymphoid tissue (bone marrow and spleen) for PFS and OS prediction in patients with r/r LBCL undergoing CAR T-cell therapy.

Methods

Study design and population

This single-center prospective study was approved by the Regional Ethics Review Board and all patients gave their informed written consent to participate. Trial inclusion criteria included relapsed/refractory CD19+ B-cell lymphoma with no other curative treatment option available, measurable disease at inclusion and Eastern cooperative oncology group performance status (ECOG PS) score 0–2. Patients with a higher ECOG PS score were considered too ill to tolerate the intensive CAR T-cell therapy [29]. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, presence of primary central nervous system lymphoma, known human immunodeficiency virus infection and an active/severe infection. The study protocol included bridging therapy of the treating clinician’s choice, with chemo- and/or radiotherapy for 4–8 weeks to reduce the tumor burden, and preconditioning with Fludarabine and Cyclophosphamide lymphodepleting therapy at 2–4 days before CAR T-cell therapy. Third generation CD19-directed CAR T-cells with CD28 and 4-1BB as co-stimulatory domains along with the CD3z signaling domain was administered as previously described [30]. A second dose of CAR T-cells was administered 4–6 weeks after the first CAR T-cell infusion if the patient did not have rapid progression or a cytokine release syndrome of ≥ grade 3.

Therapy response assessment was performed using whole body FDG PET/MR, with imaging at a minimum of two time points: pre-therapy (t0) and 3–4 weeks post-therapy (t1). Depending on clinical status, further imaging was performed 2–6 months post-therapy for a subset of patients (t2-t4).

Imaging protocol

Whole body PET/MR imaging (head to thighs) was performed 60 min post tracer injection of FDG (3 MBq/kg injection). Patients fasted for a minimum of 6 h and were confirmed to have a blood glucose level < 10 mmol/l before tracer injection. An integrated scanner capable of simultaneous time of flight PET and 3 T MR imaging was used (Signa, GE Healthcare). Acquired whole body MR sequences included free-breathing DWI (echo time (TE)/repetition time (TR) = 62/3500 ms, inversion time (TI) = 245 ms, field of view (FOV) = 440 × 352 mm2, acquisition matrix = 96 × 128, slice thickness = 6 mm, b-values = 50, 400, 900 s/mm2) and breath-hold structural T1-weighted LAVA Dixon MR (TE/TR = 4.1/1.67 ms, flip angle 12°, FOV = 500 × 450 mm2, acquisition matrix 256 × 212, slice thickness 2.5 mm). Station-wise ADC maps were calculated on the scanner console using the three acquired b-values and a mono-exponential fit. Static 3 min per bed PET images were acquired and reconstructed using an iterative algorithm (Vue point FX, 2 iterations and 28 subsets, 5 mm standard Gaussian filter, FOV 500 mm, matrix 192 × 192). A vendor-provided MR Dixon-based attenuation correction was used. SUV images normalized to body weight were calculated.

Image analysis

The Lugano classification for response assessment of lymphomas was used as reference standard [31]. Classification was performed by a Radiologist (AK) at t1.

Tumor segmentation and metric extraction

Tumors were segmented using the open source software 3DSlicer [32] by two Radiologists in consensus (AK and HA) with access to all imaging data. All visible tumors were delineated manually and separately on FDG PET, T1-weighted LAVA flex water MR and b = 900 s/mm2 DWI. For the DWI data, tumor tissue affected by motion between acquired b-value images was not segmented. Measurable tumors were defined according to Lugano classification as having a longest diameter of > 15 mm for nodal disease and > 10 cm for extra-nodal disease [31]. Corresponding lesions on pre- and post-therapy images were manually identified by a Radiologist (AK).

Quantitative and semi-quantitative tumor metrics were extracted with Matlab (R2021b). For each segmented tumor, SUVmean, SUVmax, MTV and TLG for FDG PET, volume (V) for structural MR, and ADCmean for DWI, were extracted. Whole body total tumor burden was calculated for MTV, TLG and structural volume (Vtotal). A new lesion appearing at the post-therapy scan was added to the post-therapy MTV, TLG and Vtotal if its longest diameter was > 15 mm for nodal disease and > 10 cm for extra-nodal disease on T1-weighted LAVA flex water MR. For post-therapy response assessment, the rate of change (Δ) between early post-therapy and pre-therapy extracted metrics were calculated: Δ = metric (t1) /metric (t0).

For calculation of Δ, target lesions for SUVmean, SUVmax, V and ADCmean were identified at t0 and t1 for each patient, indicated as Δ(t0) and Δ(t1), respectively. This corresponded to the most hypermetabolic tumor for SUVmean and SUVmax, the tumor with the largest volume for V, and the tumor with the most restricted diffusion for ADCmean. Different target lesions were possible in the pre- and post-therapy scans, and for different metrics.

Lymphoid tissue segmentation and metric extraction

Spleen and bone marrow were manually segmented using 3Dslicer, with separate delineations performed for FDG PET, T1-weighted LAVA flex water MR and b = 900 s/mm2 DWI. The aim was to segment normal tissue without tumor involvement. Focal disease was detected as a part of the tumor segmentation task. If diffuse infiltration was present, the affected data set was excluded from the spleen or bone marrow assessment, as applicable.

The whole spleen was segmented. Focal disease was included in the spleen volume measurement, but excluded from the SUVmean and ADCmean measurements. Diffuse tumour infiltration was deemed present if the spleen SUVmean (excluding focal disease) was higher than the SUVmean of a 3 cm circular liver reference region [31]. For bone marrow, volumes of interest for vertebral bodies were drawn to include as much as possible of the tissue while excluding tissue borders and avoiding partial volume effects. Vertebral bodies in the lumbar spine were preferentially segmented (L1-L5), but if radiotherapy to the lumbar spine was included as bridging therapy the vertebral bodies of the thoracic spine was segmented instead (T8-T12). A vertebral body was excluded if focal disease was observed. If bone marrow SUVmean was larger than the SUVmean of the liver reference region, diffuse infiltration of bone marrow was deemed present [33].

Extracted metrics for the spleen were SUVmean, V and ADCmean, and for the bone marrow SUVmean, mean FF (FFmean) and ADCmean. Rates of change were calculated.

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics are presented as the median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and as absolute values and percentages for categorical variables. Spearman’s correlation tested for associations between extracted metrics. Univariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis identified predictive indicators for PFS and OS. In addition to extracted metrics, predictor variables also included the baseline metrics age, gender and BMI at t0, and Lugano classification at t1. For pre-therapy volume metrics (MTV, TLG, V and Vtotal), the unit increase in the Cox regression analysis was changed from milliliter (ml) to deciliter (dl) for improved Hazard Ratio (HR) interpretability. For PFS, the endpoint was defined as relapse, progression, death from any cause or the time of last clinical follow-up, while for OS the endpoint was defined as death from any cause or the time of last clinical follow-up. For pre-therapy data evaluation, the starting time for PFS and OS was the date of the CAR T-cell infusion, while for post-therapy data evaluation, the starting time was set to t1. Time-to-event curves were produced using the Kaplan-Meier method for variables found statistically significant during the univariate analysis, with the difference in PFS and OS between subgroups assessed using a log-rank test. To dichotomize, median values were used. Uncorrected p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. For the univariate Cox regression analysis, correction for multiple statistical testing was performed using the false discovery rate (FDR) [34], with FDR < 0.05 considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the open-source R software (v3.6.1.).

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 24 patients were included in the study (median age 63 years, range 14–76 years, 13 females), with CAR T-cell therapy given from November 2017 to January 2020. Of the 24 patients treated, measurable disease on imaging was not observed for 6 patients, an equipment failure occurred during pre-therapy PET/MR imaging for 1 patient, and due to MR contra-indications, 1 patient underwent PET/CT imaging. This left 16 patients eligible for further PET/MR evaluation (median age 63 years, range 37–71 years, 9 females), with baseline characteristics, infusion and imaging details, and clinical outcomes of therapy shown in Table 1.

During the follow-up time, progression was seen for 15 patients and death occurred for 13 patients. The pre-therapy scan was performed at a median time of 1 day (range 0–9 days) prior to CAR T-cell therapy. The majority of patients had pre-therapy imaging after lymphodepleting therapy (n = 15), but due to imaging scheduling issues one patient had lymphodepletion performed after imaging. The median time between CAR T-cell therapy and the first post-therapy scan was 3.1 weeks (range 2.9–4.0 weeks). A second post-therapy scan was performed for nine patients, at a median time of 8.9 weeks (range 7.0–16.1 weeks) after CAR T-cell infusion. One patient had four post-therapy scans, with the third and fourth scan at 4.6 and 6.0 months post-therapy, respectively.

Extracted metrics

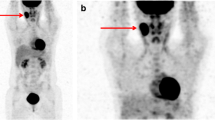

Table 2 shows a summary of extracted tumor and lymphoid tissue metrics, while example images of one patient are shown in Fig. 1. The median number of segmented lesions per patient was 4 (IQR 1–6) pre-therapy and 3 (IQR 1–6) post-therapy. The choice of target lesion for SUVmean, SUVmax and ADCmean had an impact on the rate of change calculation (Table 2). Target lesions identified on the pre-therapy scan gave median rates of change indicative of therapy response (Δ(t0): SUVmean = 0.94, SUVmax = 0.76, ADCmean = 1.17), i.e. a trend of a less aggressive disease post-therapy. The opposite was seen for target lesion identification based on the post-therapy scan (Δ(t1): SUVmean = 1.08, SUVmax = 1.02, ADCmean = 0.92).

Example patient scanned over an extended period of time. Maximum Intensity Projection (MIP) SUV images (a, b), axial b900 DW images (c, d) and line graphs of tumor SUVmax and ADCmean quantification over time (e, f). Pre-therapy (t0) and early post-therapy (t1) images are shown in inverted grey scale. A large decrease in MTV between the pre-therapy (MTV = 337 ml) and early post-therapy (MTV = 19 ml) scans was measured, as visualized by the MIP SUV images (a, b). Although this patient had a large total tumor burden pre-therapy, the OS was long (48.2 months with last follow-up as end-point). SUVmax and ADCmean tumor quantification over time (e, f), indicate an intra-tumor heterogenic response to the CAR T-cell therapy. Target lesion selection post-therapy is shown for SUVmax (red arrows) and ADCmean (blue arrows). These tumors are also highlighted in the corresponding color in the line graphs (e, f)

Example bone marrow segmentations of the lumbar spine are shown as Additional file 1. Bone marrow was segmented at the lumbar spine for 15 patients (15/16). Of these, due to focal tumor disease, the number of lumbar vertebras segmented were four in 14 patients and two in 1 patient. The thoracic spine (T11 and T12) was segmented in one patient, due to radiotherapy to the lumbar spine as part of the bridging therapy. Focal disease in the spleen was observed for one patient. Post-therapeutic bone marrow and spleen measurements were excluded in one patient because of large increases in FDG uptake of the whole bone marrow and spleen at t1, indicating diffuse infiltration. Diffuse FDG uptake in the bone marrow and spleen were not observed in any other patient (SUVmean < liver SUVmean).

Several of the extracted metrics were strongly correlated with each other (ρ > 0.6, Additional file 2). Pre-therapy SUV and volume metrics were correlated (ρ = 0.80–0.99), while pre-therapy ADCmean and volume metrics were negatively correlated (ρ = − 0.63-(− 0.70)). Rate of change metrics showed the same trend; Δ SUV and volume metrics were correlated (ρ = 0.61–0.98), while Δ(t1) ADCmean was negatively correlated to Δ(t1) SUVmax (ρ = − 0.65), Δ(t1) SUVmean (ρ = − 0.69) and Δ TLG (ρ = − 0.61).

Lugano classification at t1 was correlated with ΔSUV metrics (ρ = 0.71–0.81). In general, pre-therapy tumor metrics were not correlated with rate of change tumor metrics. The exception being a negative correlation for ADCmean pre-therapy and ADCmean Δ(t0) (ρ = − 0.61). Negative correlations between pre-therapy and rate of change metrics were also seen for lymphoid tissue, i.e. bone marrow FFmean (ρ = − 0.82) and spleen ADCmean (ρ = − 0.69). In addition, pre-therapy bone marrow and spleen SUVmean were both correlated to the tumor Δ(t1) ADCmean (ρ =0.65 and 0.72, respectively).

Survival analysis

The results of the univariate Cox regression analysis for PFS and OS are shown in Table 3. According to uncorrected p-values, statistically significant metrics were further evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method (Fig. 2). Individual bone marrow SUVmean changes between the pre-therapy and 3-week post-therapy scan evaluations are shown in Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank p-values for extracted tumor and bone marrow metrics. The median for each metric was used for thresholding. Pre-therapy results (top), showing MTV (a), and bone marrow SUVmean (b,c). Post-therapy rate of change results (bottom) showing ΔMTV (d), ΔTLG (e), and Δ(t1) ADCmean (f, g)

Individual bone marrow SUVmean changes between the pre-therapy and 3-week post-therapy scan evaluations. Patients are split according to the median pre-therapy SUVmean of 1.8., with longer PFS and OS observed for patients with higher pre-therapy bone marrow SUVmean. In general, the bone marrow SUVmean decreased post-therapy

None of the baseline metrics (age, gender and BMI) were associated with PFS or OS, neither was the Lugano classification at t1 (HR = 1.79 and p = 0.29 for PFS, HR = 1.19 and p = 0.77 for OS). The Lugano classification was grouped into responders (CMR + PMR, n = 7) and non-responders (NMR + PMD, n = 9) for the univariate Cox regression.

Tumor metrics, pre-therapy univariate analysis

For pre-therapy data, all volume metrics were significantly associated with PFS: MTV (HR = 1.48, p p < 0.001), TLG (HR = 1.02, p = 0.0054), Vtotal (HR = 1.63, p = 0.0015) and V (HR = 1.61, p = 0.013). Association with OS for pre-therapy metrics was seen for MTV (HR = 1.27, p = 0.046), TLG (HR = 1.03, p < 0.001) and V (HR = 1.90, p = 0.0043). These findings remained significant after correcting for multiple comparisons (FDR < 0.05), with the exception of pre-therapy MTV and OS (FDR = 0.19). Larger tumor volumes and/or higher tumor FDG uptake were associated with a shorter survival as measured by PFS or OS.

Kaplan Meier curves were produced, with the pre-therapy median MTV (≤39.5 ml) being the only measure able to separate patients into two groups using PFS as outcome measure (p = 0.027, Fig. 2a).

Tumor metrics, rate of change univariate analysis

Structural and metabolic total tumor burden rate of change were associated with PFS for ΔMTV (HR = 1.71, p = 0.0093), ΔTLG (HR = 1.46, p = 0.022) and ΔVtotal (HR = 1.95, p = 0.024), and with OS for ΔVtotal (HR = 1.74, p = 0.031). For these metrics, a larger increase post-therapy was associated with shorter PFS or OS. For ΔSUVmax, ΔV and ΔADCmean, the target lesion identification had to be performed post-therapy for significant association with PFS and/or OS. Δ(t1) SUVmax was associated with PFS (HR = 2.34, p = 0.011) and Δ(t1) V was associated with OS (HR = 1.09, p = 0.038). A larger increase in tumor metabolism and a larger increase in tumor volume were associated with shorter PFS and OS, respectively. Δ(t1) ADCmean was associated with both PFS (HR = 0.083, p = 0.0091) and OS (HR = 0.099, p = 0.040), with a larger decrease in ADCmean post-therapy associated with shorter PFS and OS. None of the tumor rate of change metrics remained statistically significant after correction for multiple comparisons (FDR > 0.05).

For the Kaplan Meier analysis, the median ΔMTV (≤1.35) and ΔTLG (≤1.35) were able to separate patients into two groups according to PFS (p < 0.001 for both) (Fig. 2d, e), while median Δ(t1) ADCmean (≤0.92) was able to separate patients into two groups according to both PFS (p < 0.001) and OS (p = 0.0054) (Fig. 2f, g).

Lymphoid tissue metrics, pre-therapy univariate analysis

Of the pre-therapy lymphoid tissue metrics, bone marrow SUVmean was associated with therapy outcome (Table 3). Pre-therapy bone marrow SUVmean was associated with both PFS (HR = 0.24, p = 0.0044) and OS (HR = 0.28, p = 0.014), with a higher bone marrow FDG uptake pre-therapy corresponding to longer PFS and OS. After correcting for multiple comparisons, association with PFS remained statistically significant (FDR = 0.023), while association with OS did not (FDR = 0.080). By thresholding on the median SUVmean (≤1.8), bone marrow FDG uptake was able to separate patients into two groups according to both PFS (p < 0.001) and OS (p = 0.0083) (Figs. 2b, c, 3).

For patients with pre-therapy bone marrow SUVmean > 1.8, five patients received chemotherapy and one patient received radiotherapy as bridging therapy, two patients did not receive bridging therapy. For patients with pre-therapy bone marrow SUVmean ≤ 1.8, six patients received chemotherapy and two patients received radiotherapy as bridging therapy. There was no correlation between type of bridging therapy and pre-therapy bone marrow SUVmean (ρ = 0.03).

Lymphoid tissue metrics, rate of change univariate analysis

For lymphoid tissue rate of change, no metrics were associated with PFS or OS.

Discussion

This study showed that whole body FDG PET/MR with DWI is a promising tool for predicting CAR T-cell therapy response in patients with r/r LBCL, with the total metabolic tumor burden, tumor ADCmean and FDG uptake in bone marrow unaffected by tumor infiltration being possible PET/MR parameters for prediction of PFS and OS.

In line with other imaging studies assessing predictive factors of progression after CAR T-cell therapy in LBCL [10, 11, 14, 15], the pre-therapy metabolic tumor burden was associated with outcome. A lower total tumor burden indicated longer PFS and OS. MTV, TLG and Vtotal were all statistically significant in the univariate Cox regression, but patient stratification was only possible using the MTV (median MTV ≤ 39.5 ml). Notable from Fig. 1 however, is that a high tumor burden pre-therapy does not necessarily mean a poor prognosis, as also noted by Dean et al. [10]. It is likely that a combination of imaging metrics and other biomarkers will give a more optimal prediction as described by e.g. Vercellino et al. [11], identifying lymphoma burden (MTV and lactate dehydrogenase) and extranodal involvement as risk factors for early progression after CAR T-cell therapy. Previously published thresholds for patient stratification according to MTV vary substantially, e.g. 25 ml in [14] and 147.5 ml in [10]. This is most likely due to patient heterogeneity in the relatively small cohorts studied, differences in timing of imaging (i.e. imaging before or after bridging and/or lymphodepleting therapies) and choice of tumor segmentation method.

Rates of change for total tumor burden metrics were associated with PFS according to uncorrected p-values, but not when correcting for multiple comparisons. Patient stratification was possible for ΔMTV and ΔTLG (Δ ≤ 1.35 for both). As expected, larger post-therapeutic increases in the total tumor burden were associated with poorer survival. ΔSUVmax and ΔADCmean were associated with survival if the target lesion was selected post-therapy and for uncorrected p-values (FDR > 0.05). Pre-therapy target lesion identification was not associated with PFS or OS, and neither was Lugano classification. To predict treatment response using ΔSUVmax and ΔADCmean, these results suggest that the most resistant lesion has to be identified post-therapy. In this heavily treated patient group of r/r LBCL the intra-patient tumor heterogeneity is likely to be large. Indeed, an intra-patient heterogenic response to CAR T-cell therapy was visible in patients with extended follow-up, as exemplified in Fig. 1.

Imaging studies assessing outcome prediction of CAR T-cell therapy in LBCL mainly use PET/CT scanners. The results of the present study show that PET/MR imaging can be a potential alternative. As well as providing the established benefits of FDG PET semi-quantification, this hybrid imaging modality gives the advantage of tumor ADC quantification. Due to their high cellularity and high nuclear-to-cytoplasm ratio, pre-therapy lymphoma lesions exhibit low ADC values [20]. Post-therapy, it has been suggested that response-induced cell swelling and apoptosis occur, causing an increase in tumor ADC as a sign of therapy response [21]. A link between increased ADC-values post-therapy and a favorable treatment outcome has been reported for non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients undergoing chemo- and immunochemo-therapy [22,23,24]. This is in line with the results of the current study, indicating that increased tumor ADC-values post-therapy are predictive of longer PFS and OS. Moreover, the median ADCmean rate of change measured for the cohort (Δ(t1) ≤ 0.92) allowed for patient stratification.

The tumor FDG metrics Δ(t1)MTV, Δ(t1)TLG and Δ(t1)SUVmax were all associated with PFS for uncorrected p-values, but unlike the tumor Δ(t1) ADCmean no association with OS was seen. This might indicate that the ADC is a more sensitive imaging biomarker post-therapy. One reason could be that FDG is a non-specific tracer in the sense that inflammatory changes and increased tumor metabolism are indistinguishable in the PET images [35]. Inflammatory changes post-therapy give rise to an influx of inflammatory cells, which would decrease the tumor ADC. This effect is however counteracted by oedema, cell membrane deterioration and apoptosis, giving a net effect of stable or increased tumor ADC-values for responding tumors. This is the opposite from the lowered ADC-values seen for truly progressing tumors [36]. In line with this finding, ADC has been reported to show early tumor changes in immunotherapy of glioblastoma [37, 38] and malignant melanoma [39].

ADCmean is a widely used global summary statistic of whole body DWI. There are however a large number of additional DWI metrics that could be explored, including the minimum ADC, histogram analysis (kurtosis, skewness and percentiles) and intravoxel incoherent motion, that have shown promise in various cancer applications [40]. Although this study shows preliminary findings of whole body DWI being a promising tool for very early response assessment in patients with LBCL undergoing CAR T-cell therapy, larger cohort studies using additional MR parameters are needed to fully understand the potential of PET/MRI in this context.

Lymphoid tissue assessments showed that higher pre-therapy SUVmean in the bone marrow was associated with longer PFS (p = 0.0044, FDR = 0.023) and OS (p = 0.014, FDR = 0.080), and patient stratification based on this parameter was possible according to the Kaplan-Meier analysis (median SUVmean ≤ 1.8). Interestingly, the opposite results have been reported for other cancer types treated with conventional therapies. It was published that in breast, colorectal and stomach cancer, increased pre-therapy bone marrow FDG uptake has been linked to poor survival [41,42,43,44]. For CAR T-cell therapy in lymphoma, a potential explanation is that elevated pre-therapy FDG uptake might indicate bone marrow hyperactivity as a part of a systemic immune response. This is a complex process which includes activation of bone marrow and release of chemokines and cytokines [45]. It is known that chemokines are characterised as having a dual impact on cancer [46, 47]. Chemokines induce inflammatory changes in tissues and promote tumor angiogenesis, formation of metastatic niches and cancer cell growth [48], as such promoting tumor growth and development of distant metastases. This is also known as the oncological hypothesis of metastatic growth named “seed and soil” [49, 50] suggesting that a metastatic niche is likely to appear in the proper tissue environment. On the other hand, chemokines are able to activate and attract lymphocytes which can promote CAR T-cell expansion and effector functions [51, 52], contributing to better outcome. It has been reported that chemokines promote T-cells effector functions and direct migration of the immune cells in solid tumors [53, 54]. This study suggests that this stimulatory effect of chemokines is dominant in CAR T-cell therapy in LBCL and is in line with Hirayama et al. [55], who reported that patients with increased levels of specific chemokines and cytokines (MCP-1 and IL-7) before CAR T-cell treatment had better outcomes.

Our study includes limitations. The sample size was small (n = 16), meaning multivariable statistical analysis was not possible. Many of the extracted metrics were correlated, and should be interchangeable. This study should therefore be viewed as explorative and larger studies carried out to confirm the results. Due to the explorative nature of the study, we have reported both uncorrected p-values and FDRs. The results from the former should be interpreted with caution. The lymphoid tissue assessment required delineation of tissues unaffected by tumor infiltration. A limitation of the current study is that no bone marrow biopsies were performed, as this is the standard for assessment of bone marrow involvement. Recently, it has however been reported that FDG PET has high sensitivity and specificity for detection of bone marrow involvement in aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, with a significantly higher sensitivity compared to bone marrow biopsy [33]. In addition, diffuse bone marrow infiltration is in general linked to an increased FDG uptake, and to a more aggressive disease and poorer prognosis. The results from the current study, with increased pre-therapy SUVmean being associated with longer PFS and OS, further indicates that normal bone marrow was likely measured. Usage of PET/MR instead of PET/CT was also preferential in this regard, given the advantage of MR for visualizing metastatic infiltration [56]. We set the minimum lesion size for analysis according to Lugano classification (longest diameter > 15 cm for nodal disease and > 10 cm for extra-nodal disease). As a result, partial volume effects might affect the results, in particular for SUVmean and ADCmean measurements of small lesions. This could be one potential explanation for the tumor ΔSUVmax being associated with PFS, but not the ΔSUVmean. For clinical implementation, the total tumor burden metrics used in this study have the disadvantage of requiring manual input. Ongoing developments, in particular for automated FDG tumor segmentation, are however likely to substantially decrease the manual input needed, potentially making these measurements clinically feasible. Lastly, a limitation of the current study is that an investigational product was used for the CAR T-cell therapy.

Conclusions

In r/r LBCL patients undergoing CAR T-cell therapy total metabolic tumor burden, tumor ADCmean and FDG uptake in bone marrow unaffected by tumor infiltration are possible PET/MR parameters for prediction of PFS and OS. The findings from this explorative study suggest that PET/MR can be a feasible imaging modality for CAR T-cell therapy evaluation in LBCL, and that a combination of FDG PET/MR-derived imaging metrics may be useful for therapy outcome prediction.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

19 May 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40644-023-00548-9

Abbreviations

- ADCmean :

-

Mean Apparent Diffusion Coefficient

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- CAR:

-

Chimeric Antigen Receptor

- CIT:

-

Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy

- CMR:

-

Complete Metabolic Response

- CT:

-

Computed Tomography

- DWI:

-

Diffusion Weighted Imaging

- FDG:

-

F18-Fluorodeoxyglucose

- FDR:

-

False Discovery Rate

- FFmean :

-

Mean Fat Fraction

- FOV:

-

Field of View

- HR:

-

Hazard Ratio

- LBCL:

-

Large B-cell Lymphoma

- MIP:

-

Maximum Intensity Projection

- MR:

-

Magnetic Resonance

- MTV:

-

Metabolic Tumor Volume

- NMR:

-

No Metabolic Response

- OS:

-

Overall Survival

- PET:

-

Positron Emission Tomography

- PFS:

-

Progression Free Survival

- PMD:

-

Progressive Metabolic Disease

- PMR:

-

Partial Metabolic Response

- Δ:

-

Rate of Change

- r/r:

-

relapsed/refractory

- SUVmax :

-

Maximum Standardized Uptake Value

- SUVmean :

-

Mean Standardized Uptake Value

- TLG:

-

Total Lesion Glycolysis

- TE:

-

Echo Time

- TI:

-

Inversion Time

- TR:

-

Repetition Time

- V:

-

Structural tumor volume

- Vtotal :

-

Total structural tumor volume

References

Locke FL, Ghobadi A, Jacobson CA, Miklos DB, Lekakis LJ, Oluwole OO, et al. Long-term safety and activity of axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B-cell lymphoma (ZUMA-1): a single-arm, multicentre, phase 1–2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:31–42.

Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS, Waller EK, Borchmann P, McGuirk JP, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Adult Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:45–56.

Abramson JS, Palomba ML, Gordon LI, Lunning MA, Wang M, Arnason J, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel for patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphomas (TRANSCEND NHL 001): a multicentre seamless design study. Lancet. 2020;396:839–52.

Chavez JC, Bachmeier C, Kharfan-Dabaja MA. CAR T-cell therapy for B-cell lymphomas: clinical trial results of available products. Ther Adv Hematol. 2019;10:2040620719841581.

Sterner RC, Sterner RM. CAR-T cell therapy: current limitations and potential strategies. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11:1–11.

Vercellino L, de Jong D, di Blasi R, Kanoun S, Reshef R, Schwartz LH, et al. Current and future role of medical imaging in guiding the management of patients with relapsed and refractory non-hodgkin lymphoma treated with CAR T-Cell therapy. Front Oncol. 2021;11:664688.

Cronin CG, Swords R, Truong MT, Viswanathan C, Rohren E, Giles FJ, et al. Clinical utility of PET/CT in lymphoma. AJR. 2010;194:W91–103.

Barrington SF, Mikhaeel NG, Kostakoglu L, Meignan M, Hutchings M, Müeller SP, et al. Role of imaging in the staging and response assessment of lymphoma: consensus of the International Conference on Malignant Lymphomas Imaging Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3048–58.

Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, Cavalli F, Schwartz LH, Zucca E, et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3059–68.

Dean EA, Mhaskar RS, Lu H, Mousa MS, Krivenko GS, Lazaryan A, et al. High metabolic tumor volume is associated with decreased efficacy of axicabtagene ciloleucel in large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2020;4:3268–76.

Vercellino L, Di Blasi R, Kanoun S, Tessoulin B, Rossi C, D’Aveni-Piney M, et al. Predictive factors of early progression after CAR T-cell therapy in relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2020;4:5607–15.

Hong R, Tan Su Yin E, Wang L, Zhao X, Zhou L, Wang G, et al. Tumor burden measured by 18F-FDG PET/CT in predicting efficacy and adverse effects of chimeric antigen receptor T-Cell therapy in non-hodgkin lymphoma. Front Oncol. 2021;11:713577.

Cohen D, Luttwak E, Beyar-Katz O, Hazut Krauthammer S, Bar-On Y, Amit O, et al. [18F]FDG PET-CT in patients with DLBCL treated with CAR-T cell therapy: a practical approach of reporting pre- and post-treatment studies. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2022;49:953–62.

Iacoboni G, Simó M, Villacampa G, Catalá E, Carpio C, Díaz-Lagares C, et al. Prognostic impact of total metabolic tumor volume in large B-cell lymphoma patients receiving CAR T-cell therapy. Ann Hematol. 2021;100:2303–10.

Sesques P, Tordo J, Ferrant E, Safar V, Wallet F, Dhomps A, et al. Prognostic impact of 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma treated with anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Clin Nucl Med. 2021;46:627–34.

Kuhnl A, Roddie C, Kirkwood AA, Menne T, Cuadrado M, Marzolini MAV, et al. Early FDG-PET response predicts CAR-T failure in large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2022;6:321–6.

Heacock L, Weissbrot J, Raad R, Campbell N, Friedman KP, Ponzo F, et al. PET/MRI for the evaluation of patients with lymphoma: initial observations. AJR. 2015;204:842–8.

Atkinson W, Catana C, Abramson JS, Arabasz G, McDermott S, Catalano O, et al. Hybrid FDG-PET/MR compared to FDG-PET/CT in adult lymphoma patients. Abdom Radiol. 2016;41:1338–48.

Takahara T, Imai Y, Yamashita T, Yasuda S, Nasu S, Van Cauteren M. Diffusion weighted whole body imaging with background body signal suppression (DWIBS): technical improvement using free breathing, STIR and high resolution 3D display. Radiat Med. 2004;22:275–82.

Lin C, Itti E, Luciani A, Haioun C, Meignan M, Rahmouni A. Whole-body diffusion-weighted imaging in lymphoma. Cancer Imaging. 2010;10:S172–8.

Huang MQ, Pickup S, Nelson DS, Qiao H, Xu HN, Li LZ, et al. Monitoring response to chemotherapy of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma xenografts by T2-weighted and diffusion-weighted MRI. NMR Biomed. 2008;21:1021–9.

Horger M, Claussen C, Kramer U, Fenchel M, Lichy M, Kaufmann S. Very early indicators of response to systemic therapy in lymphoma patients based on alterations in water diffusivity—A preliminary experience in 20 patients undergoing whole-body diffusion-weighted imaging. Eur J Radiol. 2014;83:1655–64.

Lin C, Itti E, Luciani A, Zegai B, Lin S, Kuhnowski F, et al. Whole-body diffusion-weighted imaging with apparent diffusion coefficient mapping for treatment response assessment in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: pilot study. Investig Radiol. 2011;46:341–9.

De Paepe KN, Van Keerberghen C-A, Agazzi GM, De Keyzer F, Gheysens O, Bechter O, et al. Quantitative whole-body diffusion-weighted MRI after one treatment cycle for aggressive non-hodgkin lymphoma is an independent prognostic factor of outcome. Radiol Imaging Cancer. 2021;3:e200061.

Cheng J, Zhao L, Zhang Y, Qin Y, Guan Y, Zhang T, et al. Understanding the mechanisms of resistance to CAR T-cell therapy in malignancies. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1237.

Schwenck J, Schörg B, Fiz F, Sonanini D, Forschner A, Eigentler T, et al. Cancer immunotherapy is accompanied by distinct metabolic patterns in primary and secondary lymphoid organs observed by non-invasive in vivo 18 F-FDG-PET. Theranostics. 2020;10:925–37.

Seith F, Forschner A, Weide B, Gückel B, Schwartz M, Schwenck J, et al. Is there a link between very early changes of primary and secondary lymphoid organs in 18F-FDG-PET/MRI and treatment response to checkpoint inhibitor therapy? J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8:e000656.

Derlin T, Schultze-Florey C, Werner RA, Möhn N, Skripuletz T, David S, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT of off-target lymphoid organs in CD19-targeting chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Ann Nucl Med. 2021;35:132–8.

Neepalu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, Lekakis LJ, Miklos DB, Jacobson CA, et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel CAR T-cell therapy in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2531–44.

Enblad G, Karlsson H, Gammelgård G, Wenthe J, Lövgren T, Amini RM, et al. A phase I/IIa trial using CD19-targeted third-generation CAR T cells for lymphoma and leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:6185–94.

Johnson SA, Kumar A, Matasar MJ, Schöder H, Rademaker J. Imaging for staging and response assessment in lymphoma. Radiology. 2015;276:323–38.

Fedorov A, Beichel R, Kalpathy-Cramer J, Finet J, Fillion-Robin J-C, Pujol S, et al. 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the quantitative imaging network. Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;30:1323–41.

Kaddu-Mulindwa D, Altmann B, Held G, Angel S, Stilgenbauer S, Thurner L, et al. FDG PET/CT to detect bone marrow involvement in initial staging of patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma: results from the prospective, multicenter PETAL and OPTIMAL>60 trials. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:3550–9.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Statist Soc B. 1995;57:289–300.

Metser U, Miller E, Lerman H, Even-Sapir E. Benign nonphysiologic lesions with increased 18F-FDG uptake on PET/CT: characterization and incidence. AJR. 2007;189:1203–10.

Reimer C, Deike K, Graf M, Reimer P, Wiestler B, Floca RO, et al. Differentiation of pseudoprogression and real progression in glioblastoma using ADC parametric response maps. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174620.

Xie T, Chen X, Fang J, Xue W, Zhang J, Tong H, et al. Non-invasive monitoring of the kinetic infiltration and therapeutic efficacy of nanoparticle-labeled chimeric antigen receptor T cells in glioblastoma via 7.0-Tesla magnetic resonance imaging. Cytotherapy. 2021;23:211–22.

Lazovic J, Jensen MC, Ferkassian E, Aguilar B, Raubitschek A, Jacobs RE. Imaging immune response in vivo: cytolytic action of genetically altered T cells directed to glioblastoma multiforme. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3832–9.

Schiza A, Irenaeus S, Ortiz-Nieto F, Loskog A, Tötterman T, Sundin A, et al. Evaluation of diffusion-weighted MRI and FDG-PET/CT to assess response to AdCD40L treatment in metastatic melanoma patients. Sci Rep. 2019;9:18069.

Messina C, Bignone R, Bruno A, Bruno A, Bruno F, Calandri M, et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging in oncology: an update. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:1493.

Lee JW, Kim SY, Han SW, Lee JE, Lee HJ, Heo NH, et al. [18F]FDG uptake of bone marrow on PET/CT for predicting distant recurrence in breast cancer patients after surgical resection. EJNMMI Res. 2020;10:72.

Bang J-I, Yoon H-J, Kim BS. Clinical utility of FDG uptake within reticuloendothelial system on F-18 FDG PET/CT for prediction of tumor recurrence in breast cancer. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0208861.

Lee JW, Lee M-S, Chung IK, Son MW, Cho YS, Lee SM. Clinical implication of FDG uptake of bone marrow on PET/CT in gastric cancer patients with surgical resection. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:2385–95.

Lee JW, Baek M-J, Ahn TS, Lee SM. Fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake of bone marrow on PET/CT can predict prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer after curative surgical resection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;30:187–94.

Zhao E, Xu H, Wang L, Kryczek I, Wu K, Hu Y, et al. Bone marrow and the control of immunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2012;9:11–9.

Propper DJ, Balkwill FR. Harnessing cytokines and chemokines for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19:237–53

Chow MT, Luster AD. Chemokines in cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2:1125–31.

Sharma G, Pothuraju R, Kanchan RK, Batra SK, Siddiqui JA. Chemokines network in bone metastasis: Vital regulators of seeding and soiling. Semin Cancer Biol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2022.02.003.

Chu JE, Allan AL. The role of cancer stem cells in the organ tropism of breast cancer metastasis: a mechanistic balance between the “seed” and the “soil”? Int J Breast Cancer. 2012;2012:209748.

Ribelles N, Santonja A, Pajares B, Llacer C, Alba E. The seed and soil hypothesis revisited: current state of knowledge of inherited genes on prognosis in breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40:293–9.

Hay KA, Hanafi L-A, Li D, Gust J, Liles WC, Wurfel MM, et al. Kinetics and biomarkers of severe cytokine release syndrome after CD19 chimeric antigen receptor–modified T-cell therapy. Blood. 2017;130:2295–306.

Deshmane SL, Kremlev S, Amini S, Sawaya BE. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1): an overview. J Interf Cytokine Res. 2009;29:313–26.

Griffith JW, Sokol CL, Luster AD. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: positioning cells for host defense and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:659–702.

Kohli K, Pillarisetty VG, Kim TS. Key chemokines direct migration of immune cells in solid tumors. Cancer Gene Ther. 2022;29:10–21.

Hirayama AV, Gauthier J, Hay KA, Voutsinas JM, Wu Q, Gooley T, et al. The response to lymphodepletion impacts PFS in patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma treated with CD19 CAR T cells. Blood. 2019;133:1876–87.

Schmidt GP, Schoenberg SO, Reiser MF, Baur-Melnyk A. Whole-body MR imaging of bone marrow. Eur J Radiol. 2005;55:33–40.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Malcolm Brenner and the Center for Cell and Gene Therapy (CAGT) at Baylor College of Medicine for producing the CAR gene vector, Pontus Blomberg, Jenny Enger and Kristina Wikström at Vecura, Karolinska Cell Therapy Center, Karolinska University Hospital, for preparation of CAR T-cells, and Research Technologists Anders Lundberg, Gunilla Arvidsson and Marie Åhlman at Uppsala University for PET/MR imaging. The authors also thank Maria Bertilsson at Uppsala Clinical Research Center for valuable advice on the statistical analysis.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Uppsala University. Swedish Cancer Society 20 1303PjF (HA); Swedish Cancer Society 19 0184Pj (ME); Swedish Research Council 2019–01326 (ME); Swedish Research Council 2019–01721 (AL).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design, CAR T-cell production and administration: AL, ME and GE. Study concept and design, medical imaging: HA. Study concept and design, image analysis: T Sjöholm, AK, JK and HA. Data acquisition and analysis, CAR T-cell administration and blood sampling: GG, TL and T Sarén. Image interpretation: AK and HA. Image analysis: T Sjöholm. Interpretation of results: T Sjöholm, AK, JK and HA. Manuscript preparation: T Sjöholm and AK. Manuscript revision, reading and approval of the final manuscript: all authors.

Authors’ information

T Sjöholm and AK contributed equally as first authors. GE and HA contributed equally as senior authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Regional Ethics Review Board (Dnr 2017/053) and all patients gave their informed written consent to participate.

Consent for publication

Our research contains no personal data.

Competing interests

JK and HA are co-founders of Antaros Medical AB. GE is a scientific advisor for Elicera Therapeutics AB and XNK Therapeutics AB and a member of the advisory board for Gilead. ME is co-founder and chief scientific officer for Elicera Therapeutics. AL is the CEO of Lokon Pharma AB, chairwoman of Repos Pharma AB and Vivolux AB as well as board member of Lokon Pharma AB, Tanea Medical AB and Aros Bioscience AB. She is alternate board member of Nexttobe AB and Almo Alo AB. Further, she holds a research grant from Lokon Pharma AB.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: there was an error in Fig. 1.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Example bone marrow segmentations.

Additional file 2.

Matrix showing the Spearman’s correlation coefficients (ρ) between extracted metrics.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sjöholm, T., Korenyushkin, A., Gammelgård, G. et al. Whole body FDG PET/MR for progression free and overall survival prediction in patients with relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphomas undergoing CAR T-cell therapy. Cancer Imaging 22, 76 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40644-022-00513-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40644-022-00513-y