Abstract

This review describes the biodegradation of Lindane (γ-hexachlorocyclohexane, γ-HCH) from the diverse sources. Environmental degradation of γ-HCH has been described in terms of integrated biological approaches such as metagenomics, cloning, phytoremediation, nanobiodegradation, and biosrfactants, genes and enzymes responsible for γ-HCH degradation and exploration of new strains of γ-HCH-degrading microbes from different environmental sources. Metagenomics-based approaches help in the identification and isolation of new genes from the uncultivable sources and provide insights for future research. There is potential in the elucidation of pathways of degradation of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) from environment by the microorganisms. This is possible by means of new/improved microbial species. The behavior of isolated strains and the microorganisms when present in community is altogether different. Therefore, there is a need to develop new technology which will identify the minor component of the microbial community involved in degradation because the minor part might have profound effect on degradation. This is mediated by the biological activity of the microbial system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The toxic organic compounds like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), chlorophenols (CPs) and dyes were continuously released into the environment by industrial and human activity. Microorganisms present in ecological sites in nature use these compounds for their metabolic activities and mediate physical and chemical change, leading to their partial or complete degradation (Raymond et al. 2001; Wiren-lehr et al. 2002). Bioremediation plays an important role in degradation of various recalcitrant and xenobiotic compounds in nature. It is mediated by a variety of microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi and actinomycetes. Lindane (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6- Hexachlorocyclohexane, γ-HCH) is a broad-spectrum chlorinated pesticide. Its production started in 1940s, after which it was used in agriculture to prevent the damage caused by vector-borne diseases. The HCH formulation is a mixture of γ-(10–12%), α- (60–70%), β- (5–12%) and δ- (6–10%) isomers. But, the only γ-HCH isomer has insecticidal activity (Li et al. 2003). Due to this feature, γ-HCH is purified to at least 99% and the remaining four isomers are discarded. They are released in the form of HCH muck (Nagata et al. 2007). The HCH isomers are hydrophobic, persistent, and ubiquitously distributed in the environment and, due to their lipophilic properties, accumulate in the food chain and lead to toxicity to living system. In the environment, it gets volatilized and transported to remote areas. Thus, HCH isomers are among the most persistent and frequently encountered pollutant in nature and contaminated sites have been reported from different parts of the world: including Brazil (Osterreicher-Cunha et al. 2003), Canada (Phillips et al. 2006), China (Zhu et al. 2005), Germany (Jürgens and Roth 1989), Greece (Golfinopoulos et al. 2003), India (Jit et al. 2011; Prakash et al. 2004), Spain (Concha-Graña et al. 2006), The Netherlands (van Liere et al. 2003), and United States (Phillips et al. 2006). The half-life period reported for lindane in soil and water was 708 and 2292 days, respectively (Beyer and Matthies 2001). Berger et al. (2016) determined the HCH derivatives in sediment, soil, water samples from contaminated riverine system from the riverine vicinity of central Germany. Because of their persistence and recalcitrance, lindane and other HCHs residues reside in the environment for a long time and have recently been detected in water, soil, sediments, plants and animals all over the world.

The traces of lindane have been detected in human fluids and tissues, such as blood, amniotic fluid, breast milk and adipose tissue (Herrero-Mercado et al. 2010). It is also reported that HCH and its isomers may cause serious damage to health in the short and long term. In mammals, acute lindane intoxication may cause respiratory dysfunction, generalized trembling, hyper-salivation, and convulsions, which can lead to death in extreme cases (Pesce et al. 2008). Lindane and other HCH isomers are endocrine disruptors, immune suppressive and as a potential carcinogens, teratogenic, genotoxic and mutagenic compounds (Salem and Das 2012). This is also reported for its neurotoxic effect due to its interference with gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurotransmitter. Chronic exposures to these compounds have been linked to renal and hepatic damages, adverse effects on reproductive system, gestation, and nervous system in mammals (Guillén-Jiménez et al. 2012; Salem and Das 2012). Besides this, lindane is also known to persist in the environment and bioaccumulate through food chain. The similar results were observed for organochlorine pesticides as well (Caicedo et al. 2011). Bioaugmentation and biostimulation by consortium in field conditions and lab-based study lead to reduction of HCH isomers through the action of consortium of strains (Garg et al.2016). Salam et al. (2017) studied bioaugmentation and phytoremediation potential of Candida VITJzN04 for lindane uptake by Saccharam sp. It was observed that half-life of lindane was decreased from 43.3 days (Saccharum alone) to 7.1 days when immobilized with yeast to plant. They also observed that a plant growth promoting yeast (Candida sp.) produces growth hormone and solubilizes insoluble phosphates in the soil.

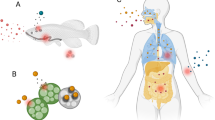

The toxicity of persistant organic pollutants (POPs) from the contaminated sites is a major problem today and this needs great attention at global level, particularly in developing countries (Bezama et al. 2008). These compounds accumulate in food chain due to their lipophilicity and biomagnification. The effects of most common organochlorine pollutants (DDT, HCH and Endosulfan) were reviewed by Mrema et al. (2013). The research in pesticide contamination needs to give attention and persistent use of these compounds will lead to contamination of soil, sediment, ground water and surface water (Mertens 2006). It is difficult to predict the fate of POPs in the environment due to rigidity of their compounds by physical, chemical, photolysis and biological degradation. Therefore, their fate can be predicted using mathematical modeling and system dynamics approach and to stimulate their fate in soil using VerisimR stimulation software (Chaves et al. 2013), time series model (Venier et al. 2012), and transgene uptake lindane system-degradation model (Zhang 2003). Milun et al. (2016) determined the effect of PCBs, organochlorine pesticides and trace metals in the tissues of bivalve molluscs, viz. Mytilus galloprovincialis, Ostrea edulis, Venus verrucosa, Arca noae and Callista chione. The fate, transport and release of pesticide into the environment are presented in Fig. 1.

The traces of HCH persist in soil for long time and reach different living organisms through food chain. On percolation in soil, it disturbs the natural microflora of soil. Therefore, there is a need of great attention for the identification of locally adapted microorganisms from the environment for the development of in situ and ex situ remediation-based environmental management programme. A diverse kind of microorganisms was characterized from the diverse habitats of the soil, industrial effluent, polluted sites and major other sites. Therefore, new strains are being constantly explored by the researchers around the world. The degrading efficiency of the isolated strains can be increased by gene cloning and co-culture-based approaches. By the development of new techniques like metagenomics and nanobiotechnology, it becomes easy to explore new microorganisms and these can be deployed in bioremediation programme. Apart from these techniques, other technological developments in microbiology, genomics, gene cloning and sequencing lead to rapid identification and characterization of useful genes. The analysis of the environment at the contaminated sites by the optimization experiments using mathematical algorithms will help us to achieve the goal in this direction. The restoration technique employed for a variety of contaminated sites cleanup programmes was reviewed by Khan et al. (2004). The high resolution technique, the magic-angle spinning (1) H-NMR spectroscopy, was used for metabolomics profiling for the assessment of phytotoxicity of organochlorine (OC) pesticides (Blondel et al. 2016). The proteomics profiling of Sphingobium indicum B90A using genome-wide expression profiling indicated the induction of lin genes (linA, linB) in the presence of four HCH isomers. Proteomic data, qPCR study and promoter analysis indicated that the upregulation of linA transcription occurs in the presence of HCH isomers (Nandavaram et al. 2016). Fungi mediate the minor change in pesticide and xenobiotic compounds by transformation in soil and this has been accessed by bacteria for degradation (Gianfreda and Rao 2004). Therefore, the fungi have been considered as a useful bioresource for the source of genes/enzymes involved in bioremediation of pesticides in the environment, viz. laccase, peroxidase, esterase, dehydrogenase, lignin peroxidase and manganese peroxidase, etc. Fungi can be a good source to study degradation mechanism induced by gene expression, degradation pathway, genes/enzymes and environmental factors affecting the bioprocess (reviewed by Maqbool et al. (2016). Muñiz et al. (2017) conducted ecotoxicological survey of soils that were polluted with lindane (γ-HCH) wastes and this affects the organochlorine compounds on microbial communities. The toxicity of these compounds was studied on native earthworm (Allolobophora chlorotica) and it was noted that the earthworm activity increases due to the biodegradation of γ-HCH, reducing the intensity of endocrine disruption in soils at low/medium contamination. This review is an attempt to describe the developments in the last decade for the degradation-based methods developed for bioremediation of lindane as contaminant from diverse ecological sources.

Degradation of lindane

HCH is ranked among the top chemical of concern by different global environmental regulatory agencies as its exposure can cause severe health effects. However, some developing countries are still using it for economic reasons. Different approaches used for decontamination of HCH are chemical treatment, incineration and land-filling. But, they lack widespread application due to cost and toxicity concerns of the living organisms. These commonly practiced methods of disposal by incineration have the potential toxic effects and also economically less viable. Therefore, keeping in view all the limitations of various physical and chemical technologies, bioremediation has been proposed as an eco-friendly and promising tool for in situ detoxification of pesticide contaminated site(s). Bioremediation of chlorinated pesticides involves bioaccumulation, biosorption and biotransformation. Different microorganisms have been reported, which utilize many halogenated compounds in the form of growth substrate (Camacho-Pérez et al. 2011). The main reaction during microbial degradation of γ-HCH is dechlorination reaction. The oxidative conversion of several halogenated organic compounds may lead to the production of acylhalides or haloaldehydes. In the process of halogen atom removal, there is risk of forming toxic intermediates. Due to their electrophilic nature, the haloaldehydes are very reactive compound and may cause cellular damage (Janssen et al. 2001).

A variety of microorganisms have been shown to degrade lindane to different rate. But, the complete/partial mineralization of this compound is mediated by several bacteria and fungi. Since long time efforts have been made for studying the lindane biodegradation by bacteria. Many researchers have reported the degradation of lindane by anaerobic bacteria, e.g., the lindane degrading strains of Clostridium sp. (MacRae et al. 1969) and E. coli (Francis et al. 1975) isolated from the rat feces. Sahu et al. (1990, 1995) reported the dechlorination of lindane by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nalin et al. (1999) isolated a new strain of Rhodanobacter lindanclasticus which degraded technical grade HCH under aerobic condition. Gupta et al. (2001) reported the degradation of γ-HCH by Alkaligens faecalis, isolated from agricultural fields. A Gram-positive Microbacterium sp. strain ITRC1 was characterized by Manickam et al. (2006). Benimeli et al. (2008) described the bioremediation of lindane-contaminated soil and its effect on maize plant. Ceci et al. (2015) investigated the potential of a saprotrophic soil fungus, Penicillium griseofulvum Dierckx to degrade β-HCH, the most recalcitrant isomer of hexachlorocyclohexane. The fungus was isolated from soils with high concentrations of HCH isomers. After GC–MS analysis, it was confirmed that β-HCH degradation was confirmed by the formation of benzoic acid derivatives as dead-end products and up to 81.4% biodegradation of the β-HCH occurs. Kaur et al. (2016) studied lignolytic potential of white rot fungi Ganoderma lucidum GL-2 grown on rice bran substrates and lindane from these residues was analyzed by GC–MS. Anacleto et al. (2017) studied the phycoremediation capacity of macroalgae Laminaria digitata for diflubenzuron and lindane pesticides and also observed the toxic effects of cadmium and copper elements which were present in seawater.

Therefore, different aerobic and anaerobic bacteria were reported in different studies for their role of halogenated compounds as growth substrate. Bioremediation of chlorinated pesticides involves pollution reduction. Here, the microorganism removes the pollutant by different mechanisms, viz. bioaccumulation, biosorption and biodegradation. This leads to the degradation of lindane by both aerobic and anaerobic metabolic pathways. The microbes have the ability to withstand the sublethal concentration of toxic compounds as they utilize these compounds as sole carbon source. Several microorganisms, fungi, cyanobacteria, and bacteria were reported to degrade γ-HCH into different metabolites. But, in anaerobic degradation few reports were published and reported in liquid and slurry cultures (Quintero et al. 2005). The role of a desorption-aid silicone oil on performance of slurry bioreactors treating a heavy soil polluted with lindane and the sequential methanogenic sulfate reducing slurry bioreactors without silicone oil shows the highest lindane removal efficiency up to 98% (Camacho-Pérez 2010a, c). The several types of microorganisms have been characterized for HCH degradation as reported in various studies (Table 1). Lal et al. (2015) determined the bacterial diversity of HCH muck disposal site and observed the degradation mediated mainly by linA and linB genes. The microbial species like Marinobacter, Sphingomonads and Chromohalobacter were dominant genera reported from the dump site. In our other study, two new strains viz. Kocuria sp. DAB-1Y and Staphylococcus sp. DAB-1 W were reported for 94 and 98% of lindane degradation, respectively, observed after 8 days of incubation in shake culture flask-based study (Kumar et al. 2016). Laquitaine et al. (2016) observed the biodegradability of HCH from agricultural soils of Guadeloupe (French West Indies).

Factors affecting lindane biodegradation

The dechlorination of lindane molecule occurs by the stepwise removal by the action of dechlorinase enzymes. Thus, the kinetics of pesticides degradation in the soil is commonly a biphasic reaction. It has a very rapid degradation rate in the beginning, followed by a very slow rate with dissipation. The remaining residues are often quite resistant to degradation (Alexander 1994). HCH biodegradation was initially thought to be an anaerobic process but the degradation was rapid under aerobic conditions. The isolation and characterization of the strains occurred by various methods (Fig. 2). Therefore, HCH degradation was influenced by temperature, pH, oxygen and biomass concentration along with many other factors. The kinetics of pesticides degradation in the soil is commonly a biphasic reaction in which rapid degradation occurs in the beginning and followed by a very slow rate in the later phase. The remaining residues are often quite resistant to degradation (Alexander 1994). When the HCH is adsorbed in the soil, the degradation rate is much slower due to mass transfer limitations (Rijnaarts et al. 1990). The ability of microbes to degrade HCH can be optimized by acclimatization of strains subsequent to higher concentration. The enzyme systems of the biodegradation pathway(s) get induced during the degradation phase and facilitate removal of the pollutant (Girish et al. 2000; Elcey and Kunhi 2010). The following section describes the factors affecting degradation of lindane:

Effect of pH on lindane degradation

It was observed that pH is one of the most important factors affecting lindane degradation and the reduction in pH may hinder the growth of the degraders during the process of degradation (Salem and Das 2012). Elcey and Kunhi (2010) reported that an acclimated consortium could degrade HCH at a wide range of pH of 3–9 with optimum at neutral pH (between pH 6–8). In contrast, Murthy and Manonmani (2007) reported that at pH 4, there was no degradation of lindane by a defined consortium of ten microorganisms. Thus, pH of the medium had a substantial effect on the survival of the members of the consortium. With an increase in pH towards neutrality, the chances of microbial survival improve gradually. The effect of pH on lindane degradation has been studied in Pandoraea sp. The optimum pH for microbial growth and biodegradation of lindane in soil slurries was 9.0 (Okeke et al. 2002). Benimeli et al. (2007) also evaluated the effect of initial pH on lindane removal by Streptomyces sp. M7 in soil extract and determined the highest pesticide removal (70%) was observed at an initial pH of 7. In another study, Salem et al. (2013) reported the optimum pH 6 for lindane degradation by Rhodotorula sp. VITJzN03.

Effect of temperature

It was reported that the optimum temperature for biodegradation of HCH isomers ranges from 25 to 30 °C in soil, soil slurry and bacterial cultures. A change in temperature up to certain limits might increase or decrease HCH removal by affecting the biological activity or by changing the levels bioavailability through reduced sorption (Phillips et al. 2005). Elcey and Kunhi (2010) evaluated lindane degradation at a wide range of temperatures and observed that chloride ions release occurred even at 5 and 60 °C (8 and 18%, respectively) whereas optimum chloride release was at 30–35 °C. Similar results were observed by Benimeli et al. (2007) and thus obtained maximum lindane removal by Streptomyces sp. M7 at 30 °C.

Effect of available form and concentration of lindane

The sorption of lindane to the surface of soil particles reduces mobility but may increase the proximity of contaminants to surface-bound microorganisms. Thus, the factors that affect solubility and sorption of lindane can influence their movement within the soil matrix and, therefore, affect their bioavailability and biodegradation. Lindane can also be volatilized through air pockets of the soil or escape from the surface affecting its concentrations in the solid and liquid phases of the soil and also its bioavailability (Phillips et al. 2005). Besides, it has been suggested that a higher silt content in soil results in higher moisture retention which may enhance bioavailability (Phillips et al. 2005). Several factors affect the volatility and bioavailability of lindane (vapor pressure, soil organic matter and moisture) and it can influence the biodegradation (Salem and Das 2012). Roy et al. (2000) also observed that with increasing water content of soil, organic material becomes hydrophilic and so the adsorption of hydrophobic compounds decreases due to hydration of the adsorbent surfaces and, thus, lowers the accessibility of the adsorption sites. Soil properties and composition can also affect lindane degradation. The organic carbon fraction of soil tends to decrease the bioavailability of organic compounds (Becerra-Castro et al. 2013). Vlčková and Hofman (2012) demonstrated that soil properties affect the bioavailability of persistent organic pollutants such as lindane, DDT, phenanthrene and pyrene. They found that an increase in the total organic carbon content of the soil caused a decrease in the bioavailability of contaminants.

The concentration of the target compound is one of the important factors that affects the biomass production and degradation rate. Low concentration of pollutant might not be able to induce the degradative enzymes activity, while too high levels may be toxic to the microorganisms (Awasthi et al. 2000). Salem et al. (2013) reported that Rhodotorula VITJzN03 which mineralizes 100% of 600 mg/l of lindane but concentrations beyond this, it inhibits the growth of the yeast in the liquid medium. Guillén-Jiménez et al. (2012) observed that an increase in lindane concentration may have an effect on lindane removal. Okeke et al. (2002) studied the ability of a Pandoreae sp. to remove lindane in liquid and soil slurry systems. They reported that lindane removal increased with increasing concentrations up to 150 mg/l and then declined at 200 mg/l. Pesce and Wunderlin (2004) showed that a bacterial consortium increased the lindane degradation rate when exposed to higher lindane concentrations but when its level increased from 0.069 to 0.412 mM, the biodegradation efficiency decreased from 100 to 83.3%, respectively. There is evidence that pesticide biodegradation rates in soil follow first-order kinetics and concentration dependent. Consequently, the lindane removal rate might decrease under these conditions. HCH also affects soil microbial populations and stimulates the growth of certain microorganisms, whereas in others case it may exert toxic effects and inhibit growth (Phillips et al. 2005). Saez et al. (2014) reported the maximum removal of lindane in soil slurries spiked with the 50 mg/kg, the highest concentration of lindane.

Effect of inoculum

The inoculum is the number of microbial cells in the active growth phase. They can also influence the biodegradation efficiency of toxic compounds. Many researchers have observed that the use of larger inoculum may enhance the lindane biodegradation efficiency (Guillén-Jiménez et al. 2012). However, lindane removal or transformation of some other pollutants is not always proportional to the inoculum size. Saez et al. (2014) observed higher lindane removal from soil slurry employing an immobilized Streptomyces consortium at 107 CFU/g of inoculum than the smaller inoculum size. However, employing higher cell densities had no additional benefits on the pesticide removal. Similar findings were reported by Fuentes et al. (2010) that the inoculum size and lindane removal rate are not directly proportional to each other. Lindane removal by Streptomyces sp. M7 in soil samples was increased when the inoculum concentration augmented from 0.5 to 2 g cells/kg soil. However, lindane removal decreased at 4 g cells/kg soil. Salam and Das (2014) also reported in case of Candida sp. VITJzN04, when the inoculum size was increased from 0.02 to 0.06 mg/l, the degradation process from 40 to 100% at the same incubation time. However, when the initial inoculum was increased further, there was no significant impact on the degradation.

Effect of additional carbon sources

Co-metabolism is a very important process for the removal of certain xenobiotics (García-Rivero and Peralta-Pérez 2008). Several researchers have demonstrated that carbon sources other than the target pollutant may influence on its degradation, but this is also governed by other factors like microbial community, concentration of pollutants and nutrients, etc. Therefore, an additional carbon source does not always stimulate the degradation process, but in some cases, it may also limit the degradation process (Pino et al. 2011). Hence, co-metabolism may be an important interaction factor to induce bioremediation. Benimeli et al. (2007) demonstrated that glucose and lindane were simultaneously consumed by Streptomyces sp. M7 and the presence of high concentrations of glucose-stimulated lindane removal and biomass yield. Guillén-Jiménez et al. (2012) suggested that the addition of agave leaves to the degrading culture medium has increased the fungal lindane degradation by biostimulation mechanism. Similarly, Alvarez et al. (2012) evaluated lindane removal by Streptomyces strains in the presence of root exudates as additional carbon source. Under this condition, Streptomycessp. A5 and M7 caused 55 and 35% of lindane removal, respectively.

Effect of nitrogen source and other supplements

Pannu and Kumar (2017) demonstrated the effect of nitrogen sources and found that addition of Beef extract greatly enhanced lindane degradation rate followed by malt extract and Peptone. The presence of yeast extract and casein showed adverse effect on lindane mineralization and decreased the degradation rate 10–50%. Guillén-Jiménez et al. (2012) evaluated the effect of some nutritional factors on lindane biodegradation by Fusarium verticillioides AT-100. They found that lindane degradation was favoured in the presence of limited amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus and without surfactant in the medium. They used higher concentrations of copper and yeast extract and found that they greatly enhanced the biodegradation process. Nagpal and Paknikar (2006) also demonstrated that lindane degradation by Conidiobolus 03-1-56 was enhanced under limited levels of nitrogen. Although nitrogen is an essential element for the growth of microorganisms at low concentrations may induce the expression of laccases and other enzymes, which degrade lignin and other xenobiotic pollutants (Guillén-Jiménez et al. 2012). The hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was used to facilitate the degradation of other organic pollutants as reported (Svrcek et al. 2010). H2O2 has been found to facilitate the degradation persistent organic pollutants, especially organochlorine pesticides. The addition of 1% H2O2 in the culture medium enhanced the dechlorination of lindane from 3 to 15% after seven days of incubation (Pannu and Kumar 2017). It might be due to increased availability of electron donor for the removal of chloride ion and oxidation of lindane.

Different approaches for lindane degradation

The diverse approaches and techniques have been used for the degradation of lindane from environment samples collected from different polluted sites. The microbial consortium, metagenomics, nanobiotechnology, gene cloning, phytoremediation, plant–microbe interactions and biosurfactant-mediated degradation are discussed below along with their successful outcomes.

Lindane degradation by microbial consortium

Microbial consortia have catalytic properties leading to partial or complete change in the chemistry of xenobiotic compounds. Microorganisms exist in nature as the microbial consortia or in multiple populations that perform complex biological and physiological processes for the survival of the community (Polti et al. 2014). The use of a single culture involves many metabolic limitations, which could be eliminated by microbial consortium or community of microorganisms (Shong et al. 2012). Several researchers have demonstrated that the isolation of consortia, both native and defined from sites, is more useful for the degradation and removal of persistent xenobiotic compounds. The prolonged exposure of microorganisms to various physiological conditions causes selective pressure on the microbes to degrade xenobiotic compound for their survival. Also, exposure of microorganisms to one or more toxic compounds for a long time possibly allowed them to evolve new catabolic enzymes to degrade such compounds (Carrillo-Pérez et al. 2004; Pino et al. 2011). Murthy and Manonmani (2007) isolated a defined microbial consortium consisting of seven Pseudomonas sp. and also Burkholderia, Flavobacterium and Vibrio genera for the degradation of γ -HCH up to a concentration of 25 ppm. It was reported that the γ-isomer (lindane) was degraded at very fast rate at all concentrations evaluated. Elcey and Kunhi (2010) isolated a lindane degrading consortium from a sugarcane field having a long history of technical-HCH application. The consortium could mineralize 300 µg/ml of lindane after 108 h of acclimation in the presence of the substrate, since no apparent accumulation of intermediary metabolites was observed. Fuentes et al. (2011) evaluated lindane removal in 57 mixed cultures of Streptomyces sp. and found that degradation was substantially improved when two, three or four strains were used in combination as compared to single cultures. Other reports also revealed the efficient use of native microbial consortia to degrade lindane and other HCH isomers. Loredana et al. (2017a, b) isolated and characterized seven bacterial species, viz., Mameliella phaeodactyli, Pseudovibrio ascidiaceicola, Oceanic aulisstylophorae, Ruegeria atlantica and to three new uncharacterized species and reported up to 97% lindane degradation associated with the sponge Hymeni acidonperlevis. Kumar et al. (2017) determined that codegradation of chlorpyrifos and lindane degradation enhanced when the two or more strain studied in bath culture degradation analysis.

Metagenomics

The uncultivable microorganism poses a problem for the identification of useful strains and we know that approximately 1% of total microorganisms on this universe are cultivable. Therefore, the metagenomic study, the total soil DNA isolated and screened the DNA library in phagemid vector and clone(s) generated were further screened for the degrading genes. A few reports were published in metagenomic analysis of microbial community of HCH degrader microorganisms. Dadhwal et al. (2009) proposed the biostimulation study for the strain isolated from HCH-contaminated site soil in India and analyzed the diversity of culturable microorganisms. Similarly, Sangwan et al. (2012) performed the soil metagenomic study of three HCH-contaminated site from India. This study found evidence for the horizontal transfer of HCH catabolic genes. The chlorpyriphos, the organophosphate containing insecticide, produces a major metabolite 3, 5, 6-trichloro-2-pyridinol (TCP) on degradation. In recombinant E. Coli, the metagenomic library was created from the sample isolated from cow rumen and characterized for tcp3A gene for degradation. This was the major breakthrough in the field of metagenomics (Math et al. 2010). The herbicides phenoxyalkanoic acid (PAA) degradation is done by novel and diverse tfdA-like genes, which are dioxygenases dependent reported in Bradyrhizobium sp., Sphingomonas spp., and uncultured soil bacteria (Zaprasis et al. 2010).

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are noted as the major cause of contamination of river sediments. DNA-stable isotope probing technique was used with metagenomics for the isolation of Achromobacter and Pseudomonas species, which reveals that the presence of biphenyl dioxygenase genes encodes for its degradation (Sul et al. 2009). Bashir et al. (2015) studied the compound-specific stable carbon isotope analysis (CSIA) for biodegradation of isomers of lindane in a contaminated aquifer from a former pesticide processing facility. A novel 2,4-dichlorophenol hydroxylase gene (tfdB-JLU) was also identified from E. coli and metagenomic library constructed for functional screening of useful gene and enzymes (Lu et al. 2011). Microbial communities were isolated from chlorinated pesticide-contaminated sites and have a profound role in biodegradation. In the γ-HCH presence, the biodegradative genes like linA reflect the ability to biodegrade POPs and this was reported in strains of Sphingomonas sp. (Manickam et al. 2010). Same metagenomic approach was applied for the identification and characterization of novel thermostable pyrethroid hydrolytic enzymes against pyrethroid pesticides from E. coli BL21 (DE3) strain (Fan et al. 2011). Fang et al. (2014) investigated the diversity of biodegrading genes and pathway of hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH), dichlorodiphenyl trichloroethane (DDT), and atrazine (ATZ) in freshwater and marine sediments by metagenomic approach by 6 datasets of 16 Gb size. This study shows that the diversity of DDGs, BDGs, HDGs, and ADGs varied with sample locations. Sangwan et al. (2014) used the metagenomic genome sequence data of two HCH-degrading Sphingobium japonicum UT26 and Sphingobium indicum B90A species. This study shows the implications of metagenomic data for ancestral genotype reconstruction. In recent study, Ivdra et al. (2017) used the multielemental (C, H, Cl) stable isotope fingerprinting for risk analysis of degradation of lindane (HCH) from source to sinks in the environment.

Nanobiotechnology

Microbial cultures have the potential for degradation of HCH; therefore, the integrated nano-biotechnological approach for the treatment of pesticides is becoming popular as a novel and effective technology. This process includes use of zerovalent granular iron or nanoparticles of iron for catalytic reductive dehalogenation of various organochlorine pesticides (Zhang 2003; Schrick et al. 2004). Paknikar et al. (2005) used an integrated nano-biotechnological approach for treatment of drinking water for elimination of pesticide residues. They synthesized FeS nanoparticles by wet chemical method and stabilized by fungal polymer. These FeS-nanoparticles carried out the dechlorination of lindane and the product was further mineralized by a bacterial culture which also degraded the fungal polymer. Similarly, electrochemical reduction of tricholoroethane using palladised iron oxide (Roh et al. 2001), reduction of carbontetrachloride by Fe2+, S2− and FeS (Assaf-Anid and Kun-Yu 2002), use of bimetallic particles for ground water treatment (Elliott and Zhang 2001), and dechlorination of lindane in multiphase catalytic reduction system with Pd/C, Pt/C and Renay/Ni have been reported as effective systems for treatment of ground water to make it free from pesticide residues (Zinovyev et al. 2004). More recently, integrated nano biotechnique was used by Singh et al. (2013) for γ-HCH degradation from contaminated soil in India. The stabilized Pd/Fe(0) bimetallic nanoparticles (CMC-Pd/Fe(0)) used Sphingomonas sp. strain NM05 for degradation of γ-HCH. Their study signifies the potential efficacy of integrated technique as an effective alternative remedial tool for γ-HCH-contaminated soil. Although the biotechnological system used for biodegradation of organochlorine (OC) pesticides are promising and effective technique, it has some limitations. For example, the precipitation of metal hydroxides on iron decrease the reactivity but this leads to increase in toxicity of the released products (Zhao 2008). Salam and Das (2015) observed the degradation of lindane by a novel bio-nano system using nanoscale zinc oxide (n-ZnO). Homolková et al. (2015) reported ferrates as an ideal chemical reagent for treatment of water contaminated with HCH. This is due to their strong oxidation potential and the absence of harmful by products. The degradation of HCH studied with ferrates under laboratory conditions and reported the formation of trichlorobenzenes and pentachlorocyclohexenes as HCH degradation products. Wu et al. (2016) used palladium nanoparticles stabilized in microcellular high-density polyethylene for lindane and hexachlorobenzenee (HCB) degradation. Yang et al. (2017) reported the nonreductive dechlorination of lindane by nitrogen containing multiwall carbon nanotubes N-MWCNTs (CNT-N1 and CNTN2) with pH (7.0–9.0) and observed the amine and pyridinic nitrogen species as basic sites responsible for the dehydrochlorination of lindane under environment conditions. They concluded that the enhanced degradation might be due to that amine and pyridinic nitrogen species. This could attack the hydrogen atom attached to the β–carbon and the dehydrochlorination of lindane followed a β-elimination mechanism. Usman et al. (2017) reported chemical oxidation of hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH) in contaminated soil under water saturated and unsaturated conditions by applying the following treatments at neutral pH: H2O2 alone, H2O2/FeII, Na2S2O8 alone, Na2S2O8/FeII, and KMnO4. They observed that more than 60% of the pollutant was lost after chemical oxidation, thereby, minimizing the non-selective behavior of chemical oxidation in soil.

Degradation by plant–microbe association

In addition to microbes, plants have been also reported to possess remarkable ability to remove or immobilize various isomers of HCH. Plant-based bioremediation techniques, based on the interactions between plants and their associated microorganisms, have been reported as cost-efficient and eco-friendly methods to clean the polluted sites. Microbe-assisted phytoremediation has been emerged as a very effective technology for removal of organic pollutants like HCH. Becerra-Castro et al. (2013) evaluated HCH removal by Cytisus striatus, a tolerant leguminous shrub, in association with different microbial inoculant treatments and confirmed that HCH dissipation was enhanced in planted pots. They inoculated substrates seeded with Cytisus striatus with Rhodococcus erythropolis ET54b and Sphingomonas sp. D4. The authors found that substrates planted with C. striatus showed a higher detoxification of HCH isomers and also both microorganisms protected the plants against the toxic effects of the contaminant. They also proposed that inoculation of C. striatus with this combination of bacterial strains can be a promising approach for the remediation of HCH-contaminated sites. Alvarez et al. (2012) also detected specific dechlorinase activity in root exudates from Zea mays, in association with Streptomyces strains improved lindane removal from the liquid medium. They evaluated the effect of maize REs on growth and γ-HCH removal by Streptomyces sp. A5 and Streptomyces sp. M7. It was reported that both strains were able to grow on minimal medium supplemented with maize REs as sole carbon source, suggesting that these microorganisms are competitive at the rhizosphere level. Fungi growing in symbiotic association with plants have unique enzymatic pathways that help to degrade pesticides that was not transformed by bacteria alone (Gianfreda and Rao 2004). For instance, mycorrhizal fungi form symbiotic association with a broad range of plant species that can contribute to plant growth and their survival by reducing stress imposed by various toxins. The effects of lindane contamination on vegetation and its associated arbuscular mycorrhizas were investigated by Sáinz et al. (2006). They found that a pre-inoculation of four plant species with Glomus deserticola isolated from the HCH contaminated soil resulted in increased growth and fungal colonization of roots. This study indicates that the fungus increases the tolerance of plant to the toxic effect of soil conditions.

Phytoremediation

Phytoremediation is focused on densely rooted, fast growing grasses and plants like Brassica sp. having fine root system. Mulberry (Morus alba L) and Poplar (Populusdeltoides) trees have been used successfully in the chlorophenols and chlorinated solvents (Stomp et al. 1993) C carries the metabolism of their xenobiotics by the reductive dehalogenation. Plants in association with microorganisms degrade, detoxify and ultimately remove pollutants from the environment. The metabolic fate of pesticide is dependent on abiotic factors (temperature, soil, moisture, pH, etc.), microbial/plant community, pesticide characteristics. Abiotic degradation is due to chemical and physical transformation of the pesticides by processes like as hydrolysis, photolysis, oxidation, reduction and rearrangements. The biotic degradation of pesticides includes the enzymatic transformation which happens mainly through the routes of phytoremediation and microbial detoxification reactions (Van Eerd 2003). Plants may carry out degradation of pesticides using anyone of the following mechanisms:

-

(i)

Oxidative transformation, e.g., metabolism of fungicide feripromorph by oxidative enzymes in cytochrome P450 (Mugin et al. 2001).

-

(ii)

Hydrolytic transformation reaction (Hoagland and Zablotowicz 2001) ester hydrolysis of thifen-sulfuron-methyl using the plant estrases having Gly-X-Ser-Gly motif (Brown and Kearney 1991).

-

(iii)

Aromatic nitroreductive metabolism of pentachloronitrobenzene in peanut (Arachis hypogaea) (Lamoureux and Rusness 1980).

-

(iv)

Carbon–phosphorous bond cleavage (not fully known mechanism in plants).

-

(v)

Pesticide conjugation reaction, i.e., (a) carbohydrate and amino-acid conjugation, e.g., biotransformation of glyphosate via. C-P lyase and glyphosate oxireductase enzymatic reactions (b) Plant glutathione conjugation reaction, e.g., increased concentration of glutathione or GSH (γ-L-glutamyl-L-cysteinyl glycine) protected wheat from phenoxaprop injury (Romano et al. 1993).

-

(vi)

Pesticide metabolism in the rhizosphere, e.g., lignolytic fungus P. chrysosporium oxidizes the insecticide lindane by putative cytochrome P450 enzyme (Mougin et al. 1996, 1997).

In rhizospheric region, plants may enhance the co-metabolism of agricultural contaminants by anyone of the following mechanisms: (i) it may allow selective enrichment of degrader organism that has low densities to significantly degrade xenobiotics in root free soil (Nichols et al. 1997), (ii) the rhizosphere may enhance the growth-linked metabolism or stimulate microbial growth by providing a natural substrate when the concentration of xenobiotics is low or unavailable (Alexander 1999; Haby and Crowley 1996), (iii) the rhizosphere is rich in natural compounds that may induce co-metabolism of xenobiotics in certain microorganisms that carry degradative genes or plasmids (Crowley et al. 1997). Verma et al. (2014) used the comparative genomics of nine Sphingobium strains (LL03, DS20, IP26, HDIPO4, P25 and RL3) which was isolated from HCH dumpsites and three existing strains (S. indicum B90A, S. japonicum UT26S and Sphingobium sp. SYK6) genome sequence used in analysis. Dubey et al. (2014) observed for phytoextraction of lindane using Spinach plant. They observed the significant difference between dissipation of lindane reported in vegetated and non-vegetated soil. Aresta et al. (2015) determined the lindane bioremediation ability of the demosponge Hymeniacidon perlevis to bioremediate lindane-polluted sea water and degradation analyzed by solid-phase micro-extraction (SPME) and determined by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS).

Pearce et al. (2015) characterized the Hexachlorocyclohexane catabolic pathway by comparative genomics of ten Sphingomonadaceae strains. This study indicated that horizontal transfer of genes mediated by insertion sequence IS6100 and further acquired in pathway. This shows a stronger association of IS6100 with lin genes in new strains reported from Czech. Chouychai et al. (2015) reported the enhanced lindane degradation by addition of three plant growth regulators, indolebutyric acid (IBA), thidiazuron (TDZ) and gibberellic acid (GA3) individually as well as in pairwise combinations. They observed that HCH concentration in the bulk soil planted with corn seeds pretreated with GA3 or TDZ + GA3 was decreased up to 97.4% and 98.4%, respectively, whereas HCH removal in soil planted with non-pretreated control waxy corn seeds was observed only up to 35.7%. The study indicates that the linA involved in phytoremediation and environmental γ-HCH degradation. This study indicated by linA gene cloning in hairy root culture of plant Cucrbita moschata (Nanasato et al. 2016). Gong et al. (2016) used the metabolic engineering of Pseudomonas putida strain KT2440 for complete mineralization of methyl parathion (MP) and γ-hexachlorocyclohexane (γ-HCH). In this paper, the functional assembly of the MP and γ-HCH was used for mineralization pathways. Asemoloye et al. (2017) studied the synergistic rhizosphere degradation of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane mediated by plant–fungal action. The strains were identified as Aspergillus niger (KY693970); Talaromyces purpurogenus (KY488468), Yarrowia lipolytica (KY488469), Talaromyces atroroseus (KY488464) and Aspergillus flavus (KY693973). They reported that combined rhizospheric action of M. maximus in combination with the fungi increased the lindane degradation rate up to 79.76, 85.93 and 88.67% degradation efficiencies in different combinational experiments.

Degradation by biosurfcatants

Biosurfactants are extracellular or membrane bound surface active compounds that are mainly produced by bacteria yeast and fungi. These are amphiphilic in nature and possess a variety of chemical structures based on their physico-chemical properties such as fatty acids, neutral lipids, phospholipid, glycolipids, lipopeptides and other polymeric molecules. Microbial-based remediation techniques for lindane-contaminated environment prove to be cost effective and environment friendly approach where the microorganisms or their products-like enzymes lead to chemical changes in these molecules. These amphiphilic biomolecules reduce the surface tension in the air/water interfaces and reduce the interfacial tension in oil/water interfaces (Pacwa-Plociniczak et al. 2011). Recently, biosurfactant (Glycolipids, Rhamnolipids, Glucose lipids, Trehalolipids, Sophorolipids, Mannosylerythritol lipids, polyol lipids, Diglycosyldiglycerides, Flavolipids) and biosurfactant producing microbes (Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Rhodococcus erythropolis, R. ruber, R. wratislaviensis, Corynebacterium sp., Mycobacterium sp., Arthrobactor sp., Candida lipolytica, Flavobacteirum sp.) are used for production of nanoparticles which will be further applicable in the area of pesticide degradation. The area of the biosurfactant-mediated process of nanoparticle synthesis is emerging as part of remediation biotechnology (Kiran et al. 2011). Biosurfactants can replace the harsh surfactant presently used in pesticide industries as these natural surfactants are found to be utilized as carbon source by soil inhabiting microbes (Lima et al. 2011). The following part of the review highlights on the reports on role of biosurfactants and biosurfactant producing microbes in agriculture sector viz. pesticide degradation (Fig. 3).

Pesticide biodegradation supported by the addition of surfactant induces the degradation of chlorinated hydrocarbon supported by glycolipids. Biosurfactant from Lactobacillus pentosus has demonstrated reduction by 59–63% of octane hydrocarbon from soil (Moldes et al. 2011), thus exhibiting the biodegradation accelerator property of biosurfactant. It has been observed that a biosurfactant producing species of Burkholderia isolated from oil-contaminated soil may be a potential candidate for bioremediation of a variety of pesticide contamination (Wattanaphon et al. 2008). Many researchers have observed that the efficiency of biosurfactant in removal of organic insoluble pollutants from soil is more as compared to synthetic surfactants. Despite the broad applications of chemical surfactants, they are environmentally hazardous and lead to ecological imbalance when accumulated above a limited concentration. In such conditions, the performance of biosurfactant is most promising and ecofriendly and hence they can act as an effective alternative to chemical surfactants.

Degradation by cloning of lin gene(s) in different host system

Both aerobic and anaerobic degradation of different isomers of HCH have been studied by various researchers. The main genes involved in the degradative pathway of lindane are the lin genes which catalyze the different reactions at different steps (Nagata et al. 1999; Kumari et al. 2002; Dogra et al. 2004; Böltner et al. 2005; Ceremonie et al. 2006; Ito et al. 2007; Nagata et al. 2007; Wu et al. 2007a, b; Yamamoto et al. 2009; Lal et al. 2010). Genes necessary for the aerobic degradation of γ-HCH (called lin genes) were initially identified and characterized for UT26 (Nagata et al. 1999) and were subsequently recovered from B90A (Dogra et al. 2004: Kumari et al. 2002). The best model system today we have is of Sphingomonads where similar lin genes are best identified and characterized (Nagata et al. 2007). In UT26 where the system is best characterized, the pathway is composed of the following genes: Lin A, Lin B, Lin C, Lin D, LinE/Eb, Lin F, Lin G, Lin H, Lin J, Lin I and Lin R, which play diverse functions during the degradation route (Ruplal et al. 2010).

The degradation pathway comprises of two parts viz. the upper and lower pathway(s), respectively. The linA to linC genes are responsible for the enzymes involved in the upper pathway, and genes linD to linJ encodes for the enzymes of the lower pathway. Nanasato et al. (2016) cloned the Sphingobium japonicum UT26 bacterial linA gene for γ-HCH degradation by hairy root culture of Cucrbita moschata plant. They observed that cultures degraded > 90% of γ-HCH (in 1 ppm concentration) and resulted in metabolite 1,2,4-trichlorobenzene and this shows that γ-HCH was degraded in the culture. This study indicates that linA shows high phytoremediation capacity of environmental HCH degradation. The effect of organochlorine (OC) pesticides was studied for Maize root metabolome. The high-resolution magic-angle spinning (1)H NMR spectroscopy is a sensitive tool for metabolomics profiling and this can be used for fast assessment of phytotoxicity of OC-pesticides (Blondel et al. 2016). Yang et al. (2016) studied that genetic engineering of microbial strain can detoxify cadmium (Cd2+), chlorpyrifos (CP) and γ-hexachlorocyclohexane (γ-HCH) simultaneously by the display of synthetic phytochelatins (EC20) and methyl parathion hydrolase (MPH) fusion protein on the cell surface of the γ-HCH degrading Sphingobium japonicum UT26 by the use of truncated ice nucleation protein (INPNC) as an anchoring motif. This study indicated that surface display of EC20 has increased the Cd2+ accumulation and protected the recombinant strain from toxic effects of Cd2+ on CP and γ‐HCH during degradation.

Conclusions

This review describes the updated information on remediation of chlorinated pesticides, particularly lindane from contaminated soil and water using biostimulation/bioaugmentation-based approaches. There is information regarding HCH degradation using metagenomcs, nanobiotechnology, phytoremediation and different biosurfactants from different contaminated sites. However, this information is insufficient and sometimes not applicable for field level studies where many parameters cannot be controlled or are less predictable. The prospects for developing economically viable HCH bioremediation technologies are based on the cloning of Lin genes and coupling of the above-said techniques. Keeping in view the health hazards and environmental impacts of the halogenated compounds, further research is needed in this direction to understand the basic mechanism of interactions of HCH-degrading microorganisms with the soil environment regulating HCH remediation. The advanced microbial and molecular approaches will provide better tools for the remediation of the most pernicious pollutants by means of exploring the novel microbial strains and/consortia.

References

Abhilash PC, Srivastava S, Singh N (2011) Comparative bioremediation potential of four rhizospheric microbial species against lindane. Chemosphere 82(1):56–63

Alexander M (1994) Biodegradation and bioremediation. Academic Press, San Diego

Alexander M (1999) Biodegradation and bioremediation. 2nd ed. San Diego, American Chemical Society. Biosciences 36:86–91

Alvarez A, Yanez ML, Benimeli CS, Amoroso MJ (2012) Maize plants (Zea mays) root exudates enhance lindane removal by native Streptomyces strains. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad 66:14–18

Anacleto P, van den Heuvel FHM, Oliveira C, Rasmussen RR, Fernandes JO, Sloth JJ, Barbosa V, Alves RN, Marques A, Cunha SC (2017) Exploration of the phycoremediation potential of Laminaria digitata towards diflubenzuron, lindane, copper and cadmium in a multitrophic pilot-scale experiment. Food Chem Toxicol 104:95–108

Anupama KS, Paul S (2010) Ex situ and in situ biodegradation of lindane by Azotobacter chroococcum. J Environ Sci Health, Part B 45:58–66

Aresta A, Nonnis Marzano C, Lopane C, Corriero G, Longo C, Zambonin C, Stabili L (2015) Analytical investigations on the lindane bioremediation capability of the demosponge Hymeniacidon perlevis. Mar Pollut Bull 90(1–2):143–149

Asemoloye MD, Ahmad R, Jonathan SG (2017) Synergistic rhizosphere degradation of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane (lindane) through the combinatorial plant-fungal action. PLoS ONE 12(8):e0183373. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183373

Assaf-Anid N, Kun-Yu L (2002) Carbon tetrachloride reduction by Fe2C, S2 K, and FeS with vitamin B-12 as organic amendment. J Environ Eng 128:94–99

Awasthi N, Ahuja R, Kumar A (2000) Factors influencing the degradation of soil applied endosulfan isomers. Soil Biol Biochem 32:1697–1705

Bajaj S, Sagar S, Khare S, Singh DK (2017) Biodegradation of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane (lindane) by halophilic bacterium Chromohalobacter sp. LD2 isolated from HCH dumpsite. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad 122:23–28

Barnhoorn IEJ, van Dyk JC, Genthe B, Harding WR, Wagenaar GM, Bornman MS (2015) Organochlorine pesticide levels in Clarias gariepinus from polluted fresh water impoundments in South Africa and associated human health risks. Chemosphere 120:391–397

Bashir S, Hitzfeld KL, Gehre M, Richnow HH, Fischer A (2015) Evaluating degradation of hexachlorcyclohexane (HCH) isomers within a contaminated aquifer using compound-specific stable carbon isotope analysis (CSIA). Water Res 71:187–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2014.12.033

Becerra-Castro C, Kidd PS, Rodríguez-Garrido B, Monterroso C, Santos-Ucha P, Prieto-Fernández A (2013) Phytoremediation of hexachlorocyclohexane(HCH) contaminated soils using Cytisusstriatus and bacterial inoculants in soils with distinctorganic matter content. Env Pollut 178:202–210

Benezet HJ, Matsumura F (1973) Isomerization of γ-BHC to α-BHC in the environment. Nature 243:480–481

Benimeli CS, Castro GR, Chaile AP, Amoroso MJ (2006) Lindane removal induction by Streptomyces sp. M7. J Basic Microbiol 46:348–357

Benimeli CS, González AJ, Chaile AP, Amoroso MJ (2007) Temperature and pH effect on lindane removal by Streptomyces sp. M7 in soil extract. J Basic Microbiol 47:468–473

Benimeli CS, Fuentes MS, Abate CM, Amoroso MJ (2008) Bioremediation oflindane-contaminated soil by Streptomyces sp. M7 and its effects on Zea mays growth. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad 61:233–239

Berger M, Löffler D, Ternes T, Heininger P, Ricking M, Schwarzbauer J (2016) Hexachlorocyclohexane derivatives in industrial waste and samples from a contaminated riverine system. Chemosphere 150:219–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.01.122

Beyer A, Matthies M (2001) Long-range transport potential of semivolatile organic chemicals in coupled air–water systems. Environ Sci Pollut Res 8(3):173–179

Bezama A, Navia R, Mendoza G, Barra R (2008) Remediation technologies for organochlorine- contaminated sites in developing countries. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol 193:1–29

Blondel C, Khelalfa F, Reynaud S, Fauvelle F, Raveton M (2016) Effect of organochlorine pesticides exposure on the maize root metabolome assessed using high-resolution magic-angle spinning (1)H NMR spectroscopy. Environ Pollut 214:539–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2016.04.057

Böltner D, Moreno-Morillas S, Ramos JL (2005) 16S rDNA phylogeny and distribution of lin genes in novel hexachlorocyclohexane-degrading Sphingomonas strains. Environ Microbiol 7(9):1329–1338

Boyle AW, Haggblom MM, Young LY (1999) Dehalogenation of lindane (γ-hexachlorocyclohexane) by anaerobic bacteria from marine sediments and by sulfate-reducing bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 29:379–387

Brown HM, Kearney PC (1991) Plant biochemistry, environmental properties and global impact of the sulfonylurea herbicides. ACS Publication, Washington DC, pp 32–49

Caicedo P, Schroder A, Ulrich N, Schroter U, Schuurmann G, Paschke A (2011) Determination of lindane leachability in soil–biosolid systems and its bioavailability in wheat plants. Chemosphere 84:397–402

Camacho-Pérez B (2010a) Biorrestauración de suelos agrícolas contaminados conagroquímicos utilizando reactores de suelos activados convencionales y electrobioquímico de nuevo tipo. Bioremediation of agricultural soils polluted with lindane using slurry bioreactors and a novel bioelectrochemical reactor. Sc D Thesis, Interim Report. CINVESTAV del IPN, México D.F., México

Camacho-Pérez B, Ríos-Leal E, Barrera-Cortés J, Esparza-García F, Rinderknecht- Seijas N, Poggi-Varaldo HM (2010) Treatment of soils contaminated with γ-hexachlorocyclohexane in sequential methanogenic-aerobic slurry bioreactors. J Biotechnol 150:559–561

Camacho-Pérez B, Ríos-Leal E, Rinderknecht-Seijas N, Poggi-Varaldo HM (2011) Enzymes involved in the biodegradation of hexachlorocyclohexane: A mini review. J Environ Manage 95(Suppl):S306–S318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2011.06.047

Carrillo-Pérez E, Ruiz-Manríquez A, Yeomans-Reina H (2004) Isolation, identification and evaluation of a mixed culture of microorganisms capable of degrading DDT (in Spanish). Revista Internacional de Contaminación Ambiental 20:69–75

Ceci A, Pierro L, Riccardi C, Pinzari F, Maggi O, Persiani AM, Gadd GM, Petrangeli Papini M (2015) Biotransformation of β-hexachlorocyclohexane by the saprotrophic soil fungus Penicillium griseofulvum. Chemosphere 137:101–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.05.074

Ceremonie H, Boubakri H, Mavingui P, Simonet P, Vogel TM (2006) Plasmid-encoded gamma-hexachlorocyclohexane degradation genes and insertion sequences in Sphingobium francense (ex-Sphingomonas paucimobilis Sp +). FEMS Microbiol Lett 257:243–252

Chaves R, López D, Macías F, Casares J, Monterroso C (2013) Application of system dynamics technique to simulate the fate of persistent organic pollutants in soils. Chemosphere 90(9):2428–2434

Chouychai W, Kruatrachue M, Lee H (2015) Effect of plant growth regulators on phytoremediation of hexachlorocyclohexane contaminated soil. Int J Phytoremediation 17(11):1053–1059. https://doi.org/10.1080/15226514.2014.989309

Concha-Graña E, Turnes-Carou MI, Muniategui-Lorenzo S, López-Mahia P, Prada-Rodriguez D, Fernández-Fernández E (2006) Evaluation of HCH isomers and metabolites in soils, leachates, river water and sediments of a highly contaminated area. Chemosphere 6:588–595

Crowley DE, Alvey S, Gilbert ES (1997) Rhizosphere ecology of xenobiotic-degrading microorganisms. In: Kruger EL, Anderson TA, Coats JR (eds) Phytoremediation of soil and water contaminants. ACS Symposium Series 777. American Chemical Society, Washington, DC, pp 20–36

Dadhwal M, Jit S, Kumari H, Lal R (2009) Sphingobium chinhatense sp. nov., a hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH)-degrading bacterium isolated from an HCH dumpsite. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 59(12):3140–3144

Datta J, Maiti AK, Modak DP, Chakrabartty PK, Bhattacharyya P, Ray KR (2000) Metabolism of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane by Arthrobacter citreus strain BI-100: identification of metabolites. J Gen Appl Microbiol 46:59–67

Dogra C, Raina V, Pal R, Suar M, Lal S, Gartemann KH, van der Meer JR, Lal R (2004) Organization of lin genes and IS6100 among different strains of hexachlorocyclohexane degrading Sphingomonas paucimobilis: evidence for horizontal gene transfer. J Bacteriol 186:2225–2235

De Paolis MR, Lippi D, Guerriero E, Polcaro CM, Donati E (2013) Biodegradation of a-, b-, and c-Hexachlorocyclohexane by Arthrobacter fluorescens and Arthrobacter giacomelloi. Appl Biochemis Biotechnol 170:514–524

Dubey RK, Tripathi V, Singh N, Abhilash PC (2014) Phytoextraction and dissipation of lindane by Spinacia oleracea L. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 109:22–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2014.07.036

Elcey CD, Kunhi AAM (2010) Substantially enhanced degradation of hexachlorocyclohexane isomers by a microbial consortium on acclimation. J Agric Food Chem 58:1046–1054

Elliott DW, Zhang WF (2001) Field assessment of nanoscale bimetallic particles for groundwater treatment. Environ Sci Technol 35:4922–4926

Fan X, Liu X, Huang R, Liu Y (2011) Identification and characterization of a novel thermostable pyrethroid-hydrolyzing enzyme isolated through metagenomic approach. Microb Cell Fact 13:11–33

Fang H, Cai L, Yang Y, Ju F, Li X, Yu Y, Zhang T (2014) Metagenomic analysis reveals potential biodegradation pathways of persistent pesticides in freshwater and marine sediments. Sci Total Environ 1(470–471):983–992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.10.076

Francis AJ, Spanggord RJ, Ouchi GI (1975) Degradation of lindane by Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol 29:567–568

Fuentes MS, Benimeli CS, Cuozzo SA, Amoroso MJ (2010) Isolation of pesticide-degrading actinomycetes from a contaminated site: bacterial growth, removal and dechlorination of organochlorine pesticides. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad 64:434–441

Fuentes MS, Saez JM, Benimeli CS, Motoso MJ (2011) Lindane biodegradation by defined consortia of indigenous Streptomyces strains. Water Air Soil Poll 222:217–231

García-Rivero M, Peralta-Pérez MR (2008) Co-metabolism in the biodegradation of hydrocarbons. Revista Mexicana de Ingeniería Biomédica 7:1–12

Garg N, Lata P, Jit S, Sangwan N, Singh AK, Dwivedi V, Niharika N, Kaur J, Saxena A, Dua A, Nayyar N, Kohli P, Geueke B, Kunz P, Rentsch D, Holliger C, Kohler HP, Lal R (2016) Laboratory and field scale bioremediation of hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH) contaminated soils by means of bioaugmentation and biostimulation. Biodegradation 7(2–3):179–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10532-016-9765-6

Gianfreda L, Rao M (2004) Potential of extra cellular enzymes in remediation of polluted soils: a review. Enzyme Microb Technol 35:339–354

Girish K, Afsar M, Radha S, Manonmani HK, Kunhi AAM (2000) Effect of induction and acclimation of a microbial consortium on its ability to degrade isomeric hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH). In: Modern trends and perspectives in food packaging for 21st century, Souvenir, 14th Indian convection of food scientists and technologists (ICFOST 2000). Central Food Technological Research Institute (CFTRI), Mysore

Golfinopoulos SK, Nikolaou AD, Kostopoulou MN, Xilourgidis NK, Vagi MC et al (2003) Organochlorine pesticides in the surface waters of Northern Greece. Chemosphere 50:507–516

Gong T, Liu R, Zuo Z, Che Y, Yu H, Song C, Yang C (2016) Metabolic Engineering of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 for Complete Mineralization of Methyl Parathion and γ-Hexachlorocyclohexane. ACS Synth Biol 5(5):434–442. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssynbio.6b00025

Guillén-Jiménez FM, Cristiani-Urbina E, Cancino-Díaz JC, Flores-Moreno JL, Barragán-Huerta BE (2012) Lindane biodegradation by the Fusarium verticillioides AT-100 strain, isolated from Agave tequilana leaves: kinetic study and identification of metabolites. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad 74:36–47

Gupta A, Kaushik CP, Kaushik A (2000) Degradation of hexacholorocyclohexane (HCH; α, β, γ and δ) by Bacillus circulans and Bacillus brevis isolated from soil contaminated with HCH. Soil Biol Biochem 32:1803–1805

Gupta A, Kaushik CP, Kaushik A (2001) Degradation of hexachlorocyclohexane isomers by two strains of Alcaligenes faecalis isolated from a contaminated site. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 66:794–800

Haby PA, Crowley DE (1996) Biodegradation of 3-chlorobenzoate as affected by rhizodeposition and selected carbon substrates. J Environ Qual 25:304–310

Herrero-Mercado M, Waliszewski SM, Valencia-Quintana R, Caba M, Hernández-Chalate F, García-Aguilar E et al (2010) Organochlorine pesticide levels in adipose tissue of pregnant women in Veracruz, Mexico. Bulletin Environ Cont Toxicol 84:652–656

Hoagland RE, Zablotowicz RM (2001) The role of plant and microbial hydrolytic enzymes in pesticide metabolism. In: Hall JC, Hoagland RE, Zablotowicz RM (eds) Pesticide biotransformation in plants and microorganisms: similarities and divergences. ACS Symposium Series 777. American Chemical Society, Washington, DC, pp 58–88

Homolková M, Hrabák P, Kolář M, Černík M (2015) Degradability of hexachlorocyclohexanes in water using ferrate (VI). Water Sci Technol 71(3):405–411. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2014.516

Huntjens JLM, Brouwer W, Grobben K, Jansma O, Scheffer F, Zehnder AJB (1988) Biodegradation of alpha-hexachlorocyclohexane by a bacterium isolated from polluted soil. In: Wolf K, van der Brink WJ, Colon FJ (eds) Contaminated Soil 88. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, pp 733–737

Imai R, Nagata Y, Senoo K, Wada H, Fukuda M, Takagi M, Yano K (1989) Dehydrochlorination of g-hexachlorocyclohexane (g-BHC) by γ-BHC-assimilating Pseudomonas paucimobilis. Agric Biol Chem 53:2015–2017

Ito M, Prokop Z, Klvana M, Otsubo Y, Tsuda M, Damborsky J, Nagata Y (2007) Degradation of beta-hexachlorocyclohexane by haloalkane dehalogenase LinB from gamma-hexachlorocyclohexane-utilizing bacterium Sphingobium sp. MI1205. Arch Microbiol 188:313–325

Ivdra N, Fischer A, Herrero-Martin S, Giunta T, Bonifacie M, Richnow HH (2017) Carbon, hydrogen and chlorine stable isotope fingerprinting for forensic investigations of hexachlorocyclohexanes. Environ Sci Technol 51(1):446–454. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b03039

Jagnow G, Haider K, Ellwardt PC (1977) Anaerobic dechlorination and degradation of hexachlorocyclohexane isomers by anaerobic and facultative anaerobic bacteria. Arch Microbiol 115:285–292

Janssen DB, Oppentocht JE, Poelarends GJ (2001) Microbial dehalogenation. Curr Opin Biotechol 12:254–258

Jit S, Dadhwal M, Kumari H, Jindal S, Kaur J et al (2011) Evaluation of hexachlorocyclohexane contamination from the last lindane production plant operating in India. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 18(4):586–597

Jürgens HJ, Roth R (1989) Case study and proposed decontamination steps of the soil and groundwater beneath a closed herbicide plant in Germany. Chemosphere 18:1163–1169

Kaur J, Moskalikova H, Niharika N, Sedlackova M, Hampl A, Damborsky J et al (2013) Sphingobium baderi sp. nov, isolated from a hexachlorocyclohexane dump site. Int J Syst Evolut Microbiol 63:673–678

Kaur H, Kapoor S, Kaur G (2016) Application of ligninolytic potentials of a white-rot fungus Ganoderma lucidum for degradation of lindane. Environ Monit Assess 188(10):588

Khan F, Husain T, Hejazi R (2004) An overview and analysis of site remediation technologies. J Environ Manage 71:95–122

Kiran GS, Selvin J, Manilal A, Sujith S (2011) Biosurfactants as green stabilizers for the biological synthesis of nanoparticles. Crit Rev Biotechnol 31(4):354–364

Kumar M, Chaudhary P, Dwivedi M, Kumar R, Paul D, Jain RK, Garg SK, Kumar A (2005) Enhanced biodegradation of β- and δ-hexachlorocyclohexane in the presence of α- and γ-isomers in contaminated soils. Environ Sci Technol 39:4005–4011

Kumar M, Gupta SK, Garg SK, Kumar A (2006) Biodegradation of hexachlorocyclohexane isomers in contaminated soils. Soil Biol Biochem 38:2318–2327

Kumar D, Kumar A, Sharma J (2016) Degradation study of lindane by novel strains Kocuria sp. DAB-1Y and Staphylococcus sp. DAB-1W. Bioresour Bioprocess 3:53–60

Kumar D, Jaswal S, Chopra S (2017) Co-degradation study of Lindane and Chlorpyrifos by novel bacterial isolates. Int J Environ Waste Manage 20(4):283–299

Kumari R, Subudhi S, Suar M, Dhingra G, Raina V, Dogra C, Lal S, Van der Meer JR, Holliger C, Lal R (2002) Cloning and characterization of lin genes responsible for the degradation of hexachlorocyclohexane isomers by Sphingomonas paucimobilis strain B90. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:6021–6028

Kuritz T, Wolk CP (1995) Use of filamentous cyanobacteria for biodegradation of organic pollutants. Appl Environ Microbiol 61:234–238

Lal R, Pandey G, Sharma P, Kumari K, Malhotra S, Pandey R, Raina V, Kohler HP-E, Holliger C, Jackson C, Oakeshott JG (2010) The biochemistry of microbial degradation of hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH) and prospects for bioremediation. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 74:58–80

Lal D, Jindal S, Kumari H, Jit S, Nigam A, Sharma P, Kumari K, Lal R (2015) Bacterial diversity and real-time PCR based assessment of linA and linB gene distribution at hexachlorocyclohexane contaminated sites. J Basic Microbiol 55(3):363–373. https://doi.org/10.1002/jobm.201300211

Lamoureux GL, Rusness DG (1980) Pentachloronitrobenzene metabolism in peanut. 1. Mass spectral characterization of seven glutathione- related conjugates produced in vivo or in vitro. Agric Food Chem 28:1057–1070

Laquitaine L, Durimel A, de Alencastro LF, Jean-Marius C, Gros O, Gaspard S (2016) Biodegradability of HCH in agricultural soils from Guadeloupe (French West Indies): identification of the lin genes involved in the HCH degradation pathway. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 23(1):120–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-015-5875-7

Li YF, Scholtz MT, Van Heyst BJ (2003) Global gridded emission inventories of beta-hexachlorocyclohexane. Environ Sci Technol 37:3493–3498

Lima TM, Procópio LC, Brandão FD, Carvalho AM, Tótola MR, Borges AC (2011) Biodegradability of bacterial surfactants. Biodegradation 22:585–592

Lodha B, Bhat P, Kumar MS, Vaidya AN, Mudliar S, Killedar DJ, Chakrabarti T (2007) Bioisomerization kinetics of γ-HCH and biokinetics of Pseudomonas aeruginosa degrading technical HCH. Biochem Eng J 35:12–19

Loredana S, Graziano P, Antonio M, Carlotta NM, Caterina L, Maria AA, Carlo Z, Giuseppe C, Pietro A (2017a) Lindane bioremediation capability of bacteria associated with the demosponge Hymeniacidon perlevis. Mar Drugs 15(4):E108. https://doi.org/10.3390/md15040108

Loredana S, Graziano P, Antonio M, Carlotta NM, Caterina L, Maria AA, Carlo Z, Corriero Giuseppe C, Pietro A (2017b) Lindane bioremediation capability of bacteria associated with the demosponge Hymeniacidon perlevis. Mar Drugs 15(108):1–15

Lu Y, Yu Y, Zhou R, Sun W, Dai C, Wan P, Zhang L, Hao D, Ren H (2011) Cloning and characterisation of a novel 2,4-dichlorophenol hydroxylase from a metagenomic library derived from polychlorinated biphenyl-contaminated soil. Biotechnol Lett 33(6):1159–1167

MacRae IC, Raghu K, Bautista EM (1969) Anaerobic degradation of the insecticide lindane by Clostridium sp. Nature 221:859–860

Manickam N, Mau M, Schlo¨mann M (2006) Characterization of the novel HCH-degrading strain, Microbacterium sp. ITRC1. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 69:580–588

Manickam N, Reddy MK, Saini HS, Shanker R (2008) Isolation of hexachlorocyclohexane-degrading Sphingomonas sp. by dehalogenase assay and characterization of genes involved in c-HCH degradation. J Appl Microbiol 104:952–960

Manickam N, Pathak A, Saini HS, Mayilraj S, Shanker R (2010) Metabolic profiles and phylogenetic diversity of microbial communities from chlorinated pesticides contaminated sites of different geographical habitats of India. J Appl Microbiol 109(4):1458–1468

Maqbool Z, Hussain S, Imran M, Mahmood F, Shahzad T, Ahmed Z, Azeem F, Muzammil S (2016) Perspectives of using fungi as bioresource for bioremediation of pesticides in the environment: a critical review. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 23(17):16904–16925. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-016-7003-8

Math RK, Asraful Islam SM, Cho KM, Hong SJ, Kim JM, Yun MG, Cho JJ, Heo JY, Lee YH, Kim H, Yun HD (2010) Isolation of a novel gene encoding a 3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinol degrading enzyme from a cow rumen metagenomic library. Biodegradation 21(4):565–573

Mertens B (2006) Microbial Monitoring and Degradation of Lindane in Soil. Ph.D. thesis, Ghent University, Belgium, ISBN 90-5989-126-0. Pp. 187

Milun V, Lušić J, Despalatović M (2016) Polychlorinated biphenyls, organochlorine pesticides and trace metals in cultured and harvested bivalves from the eastern Adriatic coast (Croatia). Chemosphere 153:18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.03.039

Miyauchi K, Suh SK, Nagata Y, Takagi M (1998) Cloning and sequencing of a 2,5-dichlorohydroquinone reductive dehalogenase gene whose product is involved in degradation of hexachlorocyclohexane by Sphingomonas paucimobilis. J Bacteriol 180:1354–1359

Mohapatra S, Pandey M (2015) Biodegradation of hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH) isomers by white rot fungus, Pleurotus florida. J Bioremed Biodeg 6:280–286

Mohn WW, Garmendia J, Galvao TC, de Lorenzo V (2006) Surveying biotransformations with a la carte genetic traps: translating dehydrochlorination of lindane (γ-hexachlorocyclohexane) into lacZ-based phenotypes. Environ Microbiol 8:546–555

Moldes AB, Paradelo R, Rubinos D, Devesa-Rey R, Cruz JM, Barral MT (2011) Ex-situ treatment of hydrocarbon-contaminated soil using biosurfactants from Lactobacillus pentosus. J Agric Food Chem 59:9443–9447

Mougin C, Pericaud C, Malosse C, Laugero C, Asther M (1996) Biotransformation of the insecticide lindane by the white rot basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Pestic Sci 47:51–59

Mougin C, Pericaud C, Dubroca J, Asther M (1997) Enhanced mineralization of lindane in soils supplemented with the white rot basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Soil Biol Biochem 29:1321–1324

Mrema EJ, Rubino FM, Brambilla G, Moretto A, Tsatsakis AM, Colosio C (2013) Persistent organochlorinated pesticides and mechanisms of their toxicity. Toxicology 10(307):74–88

Mugin CP, Corio-Costet MF, Werck-Reichhart D (2001) Plant and fungal cytochrome P-450 s: their role in pesticide transformation. ACS Publication, Washington DC, pp 166–182

Muñiz S, Gonzalvo P, Valdehita A, Molina-Molina JM, Navas JM, Olea N, Fernández-Cascán J, Navarro E (2017) Ecotoxicological assessment of soils polluted with chemical waste from lindane production: use of bacterial communities and earthworms as bioremediation tools. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 145:539–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.07.070

Murthy HMR, Manonmani HK (2007) Aerobic degradation of technical hexachlorocyclohexane by a defined microbial consortium. J Hazard Mat 149(1):18–25

Nagata Y, Miyauchi K, Takagi M (1999) Complete analysis of genes and enzymes for γ-hexachlorocyclohexane degradation in Sphingomonas paucimobilis UT26. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 23:380–390

Nagata Y, Prokop Z, Sato Y, Jerabek P, Kumar A, Ohtubo Y, Tsuda M, Damborsky J (2005) Degradation of beta-hexachlorocyclohexane by haoloalkane dehydrogenase Lin B from Sphingomonas paucimobilis UT26. App Env Microbiol 71:2183–2185

Nagata Y, Endo R, Ito M, Ohtsubo Y, Tsuda M (2007) Aerobic degradation of lindane (γ-hexachlorocyclohexane) in bacteria and its biochemical and molecular basis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 76:741–752

Nagpal V, Paknikar KM (2006) Integrated approach for the enhanced degradation of lindane. Indian J Biotechnol 5:400–405

Nalin R, Simonet P, Vogel TM, Normand P (1999) Rhodanobacter lindaniclasticus gen. nov., sp. nov., a lindane-degrading bacterium. Int J Syst Bacteriol 49:19–23

Nanasato Y, Namiki S, Oshima M, Moriuchi R, Konagaya K, Seike N, Otani T, Nagata Y, Tsuda M, Tabei Y (2016) Biodegradation of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane by transgenic hairy root cultures of Cucurbita moschata that accumulate recombinant bacterial LinA. Plant Cell Rep 35(9):1963–1974. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00299-016-2011-1

Nandavaram A, Sagar AL, Madikonda AK, Siddavattam D (2016) Proteomics of Sphingobium indicum B90A for a deeper understanding of hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH) bioremediation. Rev Environ Health 31(1):57–61. https://doi.org/10.1515/reveh-2015-0042

Nawab A, Aleem A, Malik A (2003) Determination of organochlorine pesticides in agricultural soil with special reference to c-HCH degradation by Pseudomonas strains. Biores Technol 88:41–46

Nichols TD, Wolf DC, Roders HB, Beyrouty CA, Renolds CM (1997) Rhizosphere microbial populations in contaminated soils. Water Air Soil Pollut 95:165–178

Ohisa N, Yamaguchi M (1978) Gamma-BHC degradation accompanied by the growth of Clostridium rectum isolated from paddy field soil. Agric Bio Chem 42:1819–1823

Okeke BC, Siddique T, Arbestain MC, Frankenberger WT (2002) Biodegradation of c-hexachlorocyclohexane (Lindane) and a-hexachlorocyclohexane in water and a soil slurry by a Pandoraea species. J Agric Food Chem 50:2548–2555

Osterreicher-Cunha P, Langenbach T, Torres JP, Lima AL, de Campos TM (2003) HCH distribution and microbial parameters after liming of a heavily contaminated soil in Rio de Janeiro. Environ Resource 93:316–327

Pacwa-Plociniczak M, Plaza GA, Piotrowska-Seget Z, Cameotra SS (2011) Environmental applicatications of biosurfactants: recent advances. Int J Mol Sci 12(1):633–654

Paknikar KM, Nagpal V, Pethkar AV, Rajwade JM (2005) Degradation of lindane from aqueous solutions using iron sulfide nanoparticles stabilized by biopolymers. Sci Technol Adv Mat 6:370–374

Pal R, Bala S, Dadhwal M, Kumar M, Dhingra G, Prakash O, Prabagaran SR, Shivaji S, Cullum J, Holliger C, Lal R (2005) Hexachlorocyclohexane- degrading bacterial strains Sphingomonas paucimobilis B90A, UT26 and Sp_, having similar lin genes, represent three distinct species, Sphingobium indicum sp. nov., Sphingobium japonicum sp. nov. and Sphingobium francense sp. nov., and reclassification of [Sphingomonas] chungbukensis as Sphingobium chungbukense comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 55:1965–1972

Pannu R, Kumar D (2017) Process optimization of γ- Hexachlorocyclohexane degradation using three novel Bacillus sp. strains. Biocatal Agric Biotechol 11:97–107

Pearce SL, Oakeshott JG, Pandey G (2015) Insights into ongoing evolution of the hexachlorocyclohexane catabolic pathway from comparative genomics of ten Sphingomonadaceae strains. G3 (Bethesda) 5(6):1081–1094. https://doi.org/10.1534/g3.114.015933

Pesce SF, Wunderlin DA (2004) Biodegradation of lindane by a native bacterial consortium isolated from contaminated river sediment. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad 54:255–260

Pesce SF, Cazenave J, Monferrán MV, Frede S, Wunderlin DA (2008) Integratedsurvey on toxic effects of lindane on neotropical fish: Corydoraspaleatus and Jenynsiamultidentata. Environ Pollut 156:775–783

Phillips TM, Seech AG, Lee H, Trevors JT (2005) Biodegradation of hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH) by microorganisms. Biodegradation 16:363–392

Phillips TM, Lee H, Trevors JT, Seech AG (2006) Full-scale in situ bioremediationof hexachlorocyclohexane-contaminated soil. J Chem Technol Biotech 81:289–298