Abstract

Background

The only means of achieving long-term survival in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) beyond transplant criteria is complete tumour resection. The limiting factor for curative resection in large HCC is an inadequate future liver remnant (FLR) that might culminate into post hepatectomy liver failure (PHLF). The most common method that has been employed thus far to increase the FLR is portal vein embolization (PVE), which has its own set of drawbacks mainly inadequate hypertrophy, longer duration to achieve adequate FLR and tumour progression in the waiting period. Associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS) is a novel upcoming technique that aids in achieving rapid hypertrophy of FLR, thereby facilitating resection of an otherwise unresectable tumour.

Case presentation

The authors present a case of a 46-year-old female with non-metastatic large HCC with inadequate FLR unsuitable for upfront hepatectomy. A two-stage surgical resection with ALPPS technique was preferred over PVE in this patient. This facilitated early hypertrophy of FLR and complete surgical resection of the tumour was performed successfully with an uneventful perioperative period. The patient was disease free at 16 months of follow-up.

Conclusion

ALPPS is a feasible option for otherwise unresectable large HCCs in carefully selected patients with acceptable morbidity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary liver malignancy and one of the commonest solid organ malignancies worldwide [1]. It occurs mainly in the background of chronic liver disease or cirrhosis. Tumour size larger than 10 cm is defined as large HCC and the only means of cure in such patients is complete tumour resection. Surgical resection is indicated in solitary tumour of any size, Child-Pugh class A, absence of portal hypertension or extra hepatic disease [1, 2]. Associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS) is an important and appealing alternative to PVE to induce rapid liver hypertrophy. The main indications for ALPPS are extensive bi-lobar colorectal liver metastases with a future liver remnant < 25% [3, 4]. According to the first international consensus meeting on ALPPS, the procedure is indicated in selected patients with HCC [5]. Due to higher morbidity and mortality associated with ALPPS, its use has not been widespread and should be attempted in carefully selected patients in high volume centres. It is a fairly new technique and not much literature is available with respect to the Indian population.

Case presentation

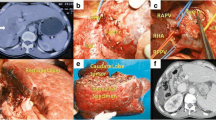

A 46-year-old lady without any co-morbidities and ECOG 1 performance status, presented with epigastric pain and weight loss of 5 months duration. She was not icteric and abdominal examination revealed a large mass arising from the liver. Blood investigations including liver function test and prothrombin time with INR were within normal limits. Abdominal ultrasound and a triphasic CT showed a large tumour (14.6 × 10.9 × 14.5 cm) occupying segments V, VII, VIII and IV of the liver with enhancement in arterial phase and washout in the portal venous phase suggestive of HCC (Fig. 1). AFP levels were 204 ng/ml. Serology for hepatitis B and C were negative. There was no evidence of extrahepatic metastases on staging workup with PET-CT. CT volumetry revealed FLR volume (segments II and III) to be 21% of total liver volume rendering it unsuitable for single stage hepatectomy. The case was discussed in a multidisciplinary meeting and ALPPS was preferred over PVE as the liver in this case was non-cirrhotic and the outcomes of ALPPS procedure performed previously at our centre were favourable. After a negative diagnostic laparoscopy for metastatic disease, partial ALPPS was performed. No liver mobilisation was done in the first stage. Portal structures were dissected, the right hepatic artery, right portal vein and right hepatic vein were looped. The right portal vein was divided and suture ligated. Segment-IV artery was identified and preserved. Liver partition was performed using a Cavitron ultrasonic surgical aspirator (CUSA). Parenchymal transection was performed till the middle hepatic vein was identified before joining the left hepatic vein (Fig. 2). Surgicel was placed over the transection plane, and the abdomen was closed over an abdominal drain. The duration of surgery was 6 h with a blood loss of 250 ml. CT volumetry was repeated on post operative day 8 which revealed the FLR volume to be 35%, a 14% increase from the baseline and adequate to obviate the risk of PHLF. The second stage of ALPPS was performed 10 days after the first stage. At exploration adequate hypertrophy of the left lateral segment was observed. The right liver lobe was mobilised. The right hepatic artery, right hepatic duct, right hepatic vein and the middle hepatic vein were divided and ligated and parenchymal transection was completed (Fig. 3). Duration of the second stage and blood loss was 4 h and 750 ml respectively. Two units of packed red blood cells were transfused. Post operative recovery of the patient was uneventful. Histopathology of the tumour was reported as well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma, T1N0M0. There was no recurrence at 16 months of follow-up. A written informed consent was obtained from the patient regarding the possible publication of the case.

Discussion

HCC is a common and heterogeneous disease. Liver resection and transplantation are the only procedures associated with long-term survival and cure of the disease. Major liver resection is feasible in patients without cirrhosis or who have well-preserved liver function and future liver remnant of at least 25%. However, it is possible in fewer than 5% of patients. Liver transplantation is indicated in patients with a single nodule up to 5 cm in size or three nodules up to 3 cm in size each [1, 2]; though beyond Milan’s criteria, recommendations have also produced good results. For large HCC in patients without cirrhosis, resection is the only option for cure.

The limiting factor for major hepatectomy in large HCCs is inadequate FLR. There are several methods to increase the FLR to obviate the risk of post hepatectomy liver failure (PHLF), the most commonly practised being portal vein embolization (PVE) [6]. The disadvantages of the procedure are mainly, inability to achieve adequate volume increase, delay of 4-6 weeks for the hypertrophy to occur and risk of progression of disease in this waiting period. Associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS) is a novel technique developed in Germany by Schnitzbauer et al. [3]. It is a two-step procedure combining parenchymal division with deportalisation of the right lobe and segment-IV in the first stage followed by completion hepatectomy in the second stage after a short interval of 7-10 days once adequate hypertrophy of FLR is achieved. The advantage is rapid and increased hypertrophy thus overcoming the disadvantages associated with PVE. It is an aggressive surgical approach for tumours considered unresectable in a single stage and an accepted alternative for a large HCC. However, it should be used selectively for patients who are not candidates for PVE due to tumour invasion of the portal vein, or as a rescue therapy after failed PVE or ligation. It can also be used as an upfront procedure and preferred over PVE in selected patients with good performance status and good liver function with HCC in a non-cirrhotic liver as in our case. It has the advantage of achieving rapid liver hypertrophy and complete tumour resection within a short interval with less incidence of post operative liver failure.

The increase in FLR volume has been reported to be between 23.8 and 200% (mean 84.16%) after an interval of 4-30 days (mean 11.6 days) between the two stages of ALPPS. In our case, there was a 14% increase in FLR after an interval of 8 days. The main drawback of ALPPS is the associated morbidity and mortality reported as 35% (range 22-90%) and 12% (range 0-28.7%) respectively [7, 8]. Increased incidence of recurrence (up to 20%) has been reported in the remnant liver, probably due to the aggressive biology of the tumour [7, 8]. However, recent results from the international ALPPS registry have shown a reduction in morbidity and mortality when performed at experienced centres. Giovanni et al. have shown that ALPPS can be performed safely in large HCC’s with acceptable overall survival and disease-free survival [9].

Conclusion

ALPPS is an appealing and feasible option for otherwise unresectable large HCCs. It provides the best chance at cure for patients who are otherwise candidates for palliative therapy. Cautious patient selection and technical expertise is of utmost importance. However, its feasibility in patients with cirrhosis and macrovascular invasion remains to be determined. As a limitation, the authors do accept that clinical data from a single patient might not yield appropriate outcomes when extrapolated to a larger population. Hence, needful larger trials are warranted.

Availability of data and materials

NA

Abbreviations

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- ALPPS:

-

Associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy

- FLR:

-

Future liver remnant

- PVE:

-

Portal vein embolization

- PHLF:

-

Post hepatectomy liver failure

- CT:

-

Computerised tomography

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- ECOG:

-

Eastern Cooperation Oncology Group

- CUSA:

-

Cavitron ultrasonic surgical aspirator

References

Carrilho FJ, Mattos AA, Vianey AF, Vezozzo DCP, Marinho F, Souto FJ et al (2015) Brazilian society of hepatology recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Arq Gastroenterol 52:2–14

Lim C, Compagnon P, Sebagh M, Salloum C, Calderaro J, Luciani A et al (2015) Hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma larger than 10 cm: preoperative risk stratification to prevent futile surgery. HPB 17:611–623

Schnitzbauer AA, Lang SA, Goessmann H, Nadalin S, Baumgart J, Farkas SA et al (2012) Right portal vein ligation combined with in situ splitting induces rapid left lateral liver lobe hypertrophy enabling 2-staged extended right hepatic resection in small-for-size settings. Ann Surg 255:405–414

Schadde E, Ardiles V, Robles-Campos R, Malago M, Machado M, Hernandez-Alejandro R et al (2014) Early survival and safety of ALPPS: first report of the international ALPPS registry. Ann Surg 260:829–838

Torres OJ, Fernandez ESM, Herman P (2015) ALPPS: past, present and future. ArqBras Cir Dig 28:155–156

Makuuchi M, Thai BL, Takayasu K, Takayama M, Kosuge T, Gunven P et al (1990) Preoperative portal embolization to increase safety of major hepatectomy for hilar bile duct carcinoma: a preliminary report. Surgery. 107:521–527

Lelpo B, Caruso R, Ferri V, Quijano Y, Duran H, Diaz E et al (2013) ALPPS procedure: our experience and state of the art. Hepatogastroenterology. 60:2069–2075

Nadalin S, Capobianco I, Li J, Girotti P, Konigsrainer I, Konigsrainer A (2014) Indications and limits for associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS). Lessons Learned from 15 cases at a single centre. Z Gastroenterol 52:35–42

Vennarecci G, Ferraro D, Tudisco A et al (2019) The ALPPS procedure: hepatocellular carcinoma as a main indication. An Italian single-center experience. Updat Surg 71(1):67–75

Acknowledgements

Dr. Swapnil Verma for proof reading and corrections of the manuscript.

Funding

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design—DS. Analysis of case data—NR,KB. Drafting of manuscript—DS and GR. Critical revision—NB. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Taken

Consent for publication

Informed written consent was taken from the patient

Competing interests

None

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bheerappa, N., Sharma, D., Gondu, G.R. et al. Large hepatocellular carcinoma conquered by ALPPS: a case report. Egypt Liver Journal 10, 40 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43066-020-00048-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43066-020-00048-6