Abstract

Background

The blaNDM-1 (New Delhi Metallo-β-lactamase-1) gene has disseminated around the globe. NDM-1 producers are found to co-harbour resistance genes against many antimicrobials, including fluoroquinolones. The spread of large plasmids, carrying both blaNDM and plasmid-mediated fluoroquinolone resistance (PMQR) markers, is one of the main reasons for the failure of these essential antimicrobials.

Methods

Enterobacteriaceae (n = 73) isolated from the blood of septicaemic neonates, admitted at a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in Kolkata, India, were identified followed by PFGE, antibiotic susceptibility testing and determination of MIC values for meropenem and ciprofloxacin. Metallo-β-lactamases and PMQRs were identified by PCR. NDM-positive isolates were studied for mutations in GyrA & ParC and for co-transmission of blaNDM and PMQR genes (aac(6′)-Ib-cr, qnrB, qnrS) through conjugation or transformation. Plasmid types, integrons, plasmid addiction systems, and genetic environment of the blaNDM gene in NDM-positive isolates and their transconjugants/ transformants were studied.

Results

Isolated Enterobacteriaceae comprised of Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 55), Escherichia coli (n = 16), Enterobacter cloacae (n = 1) and Enterobacter aerogenes (n = 1). The rates of ciprofloxacin (90%) and meropenem (49%) non-susceptibility were high. NDM was the only metallo-β-lactamase found in this study. NDM-1 was the predominant metallo-β-lactamase but NDM-5, NDM-7, and NDM-15 were also found. There was no significant difference in ciprofloxacin non-susceptibility (97% vs 85%) and the prevalence of PMQRs (85% vs 77%) between NDM-positive and NDM-negative isolates. Among the PMQRs, aac(6′)-Ib-cr was predominant followed by qnrB1 and qnrS1. Twenty-nine isolates (40%) co-harboured PMQRs and blaNDM, of which 12 co-transferred PMQRs along with blaNDM in large plasmids of IncFIIK, IncA/C, and IncN types. Eighty-two percent of NDM-positive isolates possessed GyrA and/or ParC mutations. Plasmids carrying only blaNDM were of IncHIB-M type predominantly. Most of the isolates had ISAba125 in the upstream region of the blaNDM gene.

Conclusion

We hypothesize that the spread of PMQRs was independent of the spread of NDM-1 as their co-transfer was confirmed only in a few isolates. However, the co-occurrence of these genes poses a great threat to the treatment of neonates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Fluoroquinolones are considered as critically important antimicrobials by the World Health Organization [1]. They are used extensively to treat gram-negative and some selective gram-positive bacteria. Quinolones (Nalidixic acid) and fluoroquinolones (Ciprofloxacin, gatifloxacin etc.) are bactericidal antimicrobials that selectively target the action of gyrase and topoisomerase IV disabling the DNA replication [2]. The classical mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance are the accumulation of mutations in the target enzymes and upregulation of the efflux pumps. Both these mechanisms are mutational and are passed vertically to the surviving progeny. Adding fuel to this fire are the plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance (PMQR) genes which raise greater concern because of their transmissibility. PMQRs include pentapeptide Qnr protein genes (qnrA, qnrB, qnrS, qnrC, qnrD) which give protection to gyrase and topoisomerase IV, fluoroquinolone modifying enzyme aac(6′)-Ib-cr which is a variant of the acetyltransferase of aminoglycosides, and plasmid DNA encoded efflux pumps qepA and OqxAB. Although PMQRs confer low-level resistance, they facilitate the selection of mutations in gyrase and topoisomerase genes which results in high-level resistance [3].

With the emergence of carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae, treatment options have been severely jeopardized. Though a number of carbapenemases (IMP, VIM, SIM, SPM, GIM, KPC, SME) have been identified in Enterobacteriaceae, the advent of NDM-1 has been the ‘last straw’ in this growing problem. This study focuses on blaNDM-1 instead of other carbapenemases because it is widely prevalent in India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan [4]. It is a metallo-β-lactamase that contains zinc at its active site and can hydrolyze not only carbapenems but almost all hydrolyzable β-lactams except aztreonam [4]. Apart from resistance to β-lactam antibiotics, most blaNDM-1 carrying Enterobacteriaceae are also resistant to a wide range of non-β-lactam antibiotics such as aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, sulphonamides, trimethoprim, chloramphenicol [5].

Both PMQRs and NDM-1 are present on transmissible elements and several studies have shown the presence of PMQRs with blaNDM [5, 6]. With increasing resistance to carbapenems, and concurrent resistance to fluoroquinolones in NDM-possessing isolates, a better understanding of this association is necessary. This study focuses on fluoroquinolone non-susceptibility and prevalence of PMQRs in NDM-positive and NDM-negative Enterobacteriaceae isolated from cases of neonatal septicaemia. It also highlights the possibility of co-transmission of these resistance genes in single large conjugative plasmids.

In developing countries neonates are prescribed fluoroquinolones for life-threatening infections [7] and so are carbapenems [8]. A thorough evaluation of their resistance level also makes this study clinically relevant.

Materials and methods

Identification of strains

Enterobacteriaceae (n = 73) obtained from blood cultures of 66 septicaemic neonates (new-borns less than 28 days of life), admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit of IPGMER and SSKM Hospital, Kolkata, India, during January 2012 to June 2014, were included in this study. The isolates were identified by 5 biochemical tests which include Triple Sugar Iron test, Mannitol motility test, Simmons citrate agar test, Urease test, Indole test, and discrepancies were resolved by Vitek2 system (bioMe’rieux, Marcy l’E’toile, France). Due to unavoidable circumstances, isolates were not collected between 2012 June to 2012 December.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing and determination of MIC values

The antimicrobial susceptibility testing for different antibiotic agents (piperacillin (100 μg), cefotaxime (30 μg), cefoxitin (30 μg), aztreonam (30 μg), meropenem (10 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), ofloxacin (5 μg), amikacin (30 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), tigecycline (15 μg), and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (1.25 μg /23.75 μg) (BD Diagnostics, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was done by the Kirby-Bauer standard disk diffusion method. The MIC values (mg/L) of meropenem and ciprofloxacin were determined using Etest (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden). All the values were interpreted according to CLSI guidelines [9] except for tigecycline, which was interpreted according to EUCAST guidelines 2013 [10]. MIC50 and MIC90 (MIC at which 50 and 90% of the isolates were inhibited respectively) were calculated for meropenem and ciprofloxacin.

Genotypic detection of resistance markers

PCR assays were performed on all isolates for the detection of carbapenemase genes (blaNDM, blaVIM, blaIMP, blaSPM, blaGIM, blaSIM, blaKPC, blaOXA-48) [8, 11,12,13], other β-lactamase genes (blaCTX-M, blaTEM, blaSHV, blaOXA-1) [14, 15] and PMQR genes (qnrA, qnrB, qnrS, qnrC, qnrD, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, qepA, oqxA, oqxB) [3, 16]. The qepA and aac(6′)-Ib-cr genes were analyzed by a multiplex PCR with a buffer suitable for GC rich sequences as the GC content of qepA gene is high (70%). The aac(6′)-Ib-cr was differentiated from its wild-type allele by digestion with BtsCI enzyme (New England Biolabs, Massachusetts) [16]. Primers used do not discard the presence of the non-ESBL variants of blaTEM and blaSHV. As the study focuses on blaNDM-1 and PMQRs, the PCR products of blaTEM and blaSHV genes were not further sequenced and this remains a shortcoming of the study.

Sequencing

All blaNDM and qnrB amplified products were sequenced using primers described previously [17, 18]. qnrS was amplified with a pair of primers designed in this study:- qnrSF5’- TCTAGCCCTCCTTTCAACAAG-3′ and qnrSR:5′- TGAGCGTTTAAAATCACACATCA-3′. Additionally, in NDM-positive isolates, quinolone resistance determining region (QRDR) of gyrA and parC genes were sequenced [19]. Sequencing was carried out using Big-Dye terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA) in an automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems 3730DNA Analyzer, Perkin Elmer, USA).

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE)

Genetic relatedness of the isolates was examined by PFGE in a CHEF-DRIII apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, and CA) following digestion of genomic DNA with XbaI enzyme (New England Biolabs, Massachusetts) according to Tenover et al. [20]. The PFGE images were processed and the dendrogram was calculated by FPQuest software v4.5 (Biorad laboratories inc, Hercules, California, USA.) using Dice coefficient and UPGMA (unweighted pair group method using arithmetic averages). Isolates having more than 95% similarity were considered identical.

Molecular characterization of NDM-positive isolates with a focus on fluoroquinolone resistance

Transmissibility of blaNDM was studied by conjugation experiment. In the solid mating assay, donor strain and recipient strain (Escherichia coli J53 azide resistant) were plated in a ratio of 1:5 on Luria Agar plates and incubated at 37 °C. Transconjugants were selected on two types of agar plates containing: (A) cefoxitin (10 mg/L) and sodium azide (100 mg/L) and (B) ciprofloxacin (0.06 mg/L) and sodium azide (100 mg/L), as recommended by earlier studies [21, 22]. Isolates which could not transfer their plasmid through conjugation were subjected to electro-transformation using E. coli DH10B as host cells. Transformants were selected in LA plates containing cefoxitin (5 mg/L). In one case where there was no colony on cefoxitin plate, transformants were selected on ampicillin (50 mg/L) agar plate. The transconjugants /transformants were screened for the presence of the blaNDM gene, PMQRs (aac(6′)-Ib-cr, qnrB and qnrS), β-lactamases (blaCTX-M, blaTEM, blaSHV, blaOXA-1), and 16S rRNA methylases (armA, rmtB, rmtC, rmtA, npmA, rmtD) [23].

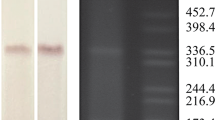

Plasmid DNA was isolated from wild-type and transconjugants/transformants by modified Kado and Liu plasmid isolation technique [24] and was sized by Quantity One® 1-D analysis software (Biorad) comparing with plasmids of E. coli V517 and Shigella flexineri YSH6000. Plasmid addiction systems (pemKI, ccdAB, relBE, parDE, vagCD, hok–sok, pndCA, srnBC) were investigated by PCR assays [25]. Plasmid types were also determined by PBRT kit (Diatheva srl, Cartoceto, Italy). Presence of class 1, class 2, and class 3 integrons was investigated [26].

The upstream and downstream regions of blaNDM were amplified and sequenced with a series of primers which were designed previously [27].

Statistics

Determination of significant differences between NDM-positive isolates and NDM-negative isolates and between organisms Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae was calculated using the chi-square test of independence by comparing the variables. All statistical testing was two-tailed and all comparisons were unpaired. Statistical significance was defined as P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Isolates

Seventy-three isolates were identified as Enterobacteriaceae which included Klebsiella pneumoniae (75%, 55/73), Escherichia coli (22%, 16/73), Enterobacter cloacae (1%, 1/73) and Enterobacter aerogenes (1%, 1/73).

Antibiotic susceptibility pattern

Ninety-seven percent (71/ 73) of the isolates were multidrug resistant (MDR) i.e. non-susceptible to three or more groups of antibiotics. Thirty isolates were resistant to 7 groups of antibiotics. Isolates were highly resistant to most of the antibiotics except meropenem and tigecycline, resistance was generally higher in K. pneumoniae than E. coli. Non-susceptibility to different antibiotics for all isolates is depicted in Table 1 and Additional file 1. Enterobacter aerogenes and Enterobacter cloacae were non-susceptible to piperacillin, cefotaxime, cefoxitin, ciprofloxacin, and aztreonam. Additionally, Enterobacter aerogenes was non-susceptible to meropenem and Enterobacter cloacae isolate was non-susceptible to gentamicin.

Since this study focuses on carbapenem and fluoroquinolone resistance, analysis of the isolates was carried out in terms of these two antibiotics separately. Forty-nine percent (36/73) of the total isolates were non-susceptible to meropenem and nearly all (97%, 35/36) meropenem non-susceptible isolates, were non-susceptible to ciprofloxacin, which included E. coli (n = 6), K. pneumoniae (n = 29) and Enterobacter aerogenes (n = 1). Eighty-four percent (31/37) of the meropenem susceptible isolates were also non-susceptible to ciprofloxacin. Overall, ciprofloxacin non-susceptibility (90%) was higher than meropenem non-susceptibility (49%).

The range of MIC against meropenem in E. coli was 0.032 mg/L to > 32 mg/L and in K. pneumoniae was 0.023 mg/L to 32 mg/L. Whereas, MIC against ciprofloxacin in E. coli was 0.25 mg/L to > 32 mg/L and in K. pneumoniae was 0.064 mg/L to > 32 mg/L. The MIC of meropenem in Enterobacter aerogenes and Enterobacter cloacae were 4 mg/L and 0.047 mg/L respectively whereas MIC of ciprofloxacin were 4 mg/L and 15 mg/L. In E. coli isolates MIC50 and MIC 90 of meropenem were 0.125 mg/L and 24 mg/L respectively and in K. pneumoniae isolates MIC50 and MIC90 of meropenem were 1.5 mg/L and 10 mg/L respectively. In both organisms, MIC50 and MIC90 of ciprofloxacin were > 32 mg/L.

Prevalence of various β-lactamases and PMQRs

Since blaNDM-1 genes can persist even in cells exhibiting very low-level resistance to meropenem [28], all isolates were screened for blaNDM and other carbapenemases. Forty-seven percent (34/73) isolates were blaNDM-positive which included 6 E. coli, 27 K. pneumoniae, and 1 Enterobacter aerogenes isolate. No other metallo-β-lactamase was found. Sequencing of blaNDM amplified product revealed that most of them were blaNDM-1, except 3 which were blaNDM-5, blaNDM-7 and blaNDM-15. The blaNDM-15 was a novel variant and the sequence was submitted to GenBank (accession no. KP735848). Two isolates non-susceptible to meropenem, yet lacking blaNDM, possessed blaOXA-48. blaKPC was not present in any of the isolates. β-lactamase genes blaCTX-M, blaSHV, blaTEM, blaOXA-1 were present in 66% (48/73), 49% (36/73), 42% (31/73) and 66% (48/73) isolates respectively (Table 2, Additional file 1).

Overall 81% (59/73) isolates were confirmed to carry at least one of the PMQRs which included 7 E. coli isolates, 50 K. pneumoniae isolates and both the Enterobacter sp. Overall, 40% (29/73) isolates co-harboured NDM and PMQRs. Among qnr genes, qnrB and qnrS were present in 51% (37/73) and 3% (2/73) of isolates respectively. Other qnr genes qnrA, qnrC, and qnrD were absent. All qnrB and qnrS genes found were qnrB1 and qnrS1 respectively. Seventy-one percent (52/73) isolates were positive for modifying enzyme coding aac(6′)-Ib-cr gene. Fourteen isolates carried both the aac(6′)-Ib and aac(6′)-Ib-cr alleles. None of the isolates carried plasmid-mediated efflux pump gene qepA. MDR family efflux pump genes oqxA and oqxB were found in 53 K. pneumoniae and 2 E. coli isolates. Prevalence of aac(6′)-Ib-cr in K. pneumoniae 80% (44/55) was significantly higher than E. coli 44% (7/16) (P-value 0.0117). In K. pneumoniae prevalence of qnrB and qnrS were 64% (35/55) and 4% (2/55) respectively but these genes were absent in E. coli (Table 2).

Distribution of PMQRs in NDM-positive and NDM-negative isolates

An analysis of the distribution of PMQRs was carried out in NDM-positive and NDM-negative isolates. PMQR genes were highly abundant in both NDM-positive isolates (85%, 29/34) and NDM-negative isolates (77%, 30/39) (Table 3). Ninety-seven percent (33/34) NDM-positive isolates were non-susceptible to ciprofloxacin against 85% (33/39) of the NDM-negative isolates. Prevalence of aac(6′)-Ib-cr (82%,) and qnrB (56%) was higher in NDM-positive isolates than NDM-negative isolates (62 and 46% respectively). Of all isolates, qnrS was found only in 2 isolates which also possessed NDM (Table 3). Since oqxA and oqxB genes are mostly chromosomally located in K. pneumoniae [29], we have excluded this from the calculation of the total percentages of PMQRs.

Relatedness of the studied isolates based on PFGE patterns

According to the cladogram, majority (12/16) of the E. coli isolates were diverse (Fig. 1a), except 4 isolates which were indistinguishable and grouped as cluster A. However, the cladogram of K. pneumoniae showed (Fig. 1b) that many isolates were indistinguishable. They were grouped into 6 clusters (cluster B – G). Cluster B, C, D, F, and G include 2–4 identical isolates. Cluster E was the largest cluster which included 9 isolates. The presence of a higher number of clonal isolates in K. pneumoniae may have contributed to the higher rate of fluoroquinolone non-susceptibility and prevalence of PMQRs in K. pneumoniae compared to E. coli.

Genetic relatedness of (a) E. coli and (b) K. pneumoniae isolates. Analysis of PFGE of XbaI digestion pattern based on Dice’s similarity co-efficient and UPGMA (the position tolerance and optimization were set at 1.5 and 1.5% respectively). More than 95% similarity in PFGE band pattern was interpreted as indistinguishable

Detailed molecular characterization of NDM-possessing isolates with a focus on co-transfer of bla NDM and PMQRs

Study of the mutations in GyrA and ParC in NDM-possessing isolates

Since fluoroquinolone resistance in Enterobacteriaceae results also from the accumulation of mutations primarily in DNA gyrase (GyrA) and then in topoisomerase IV (ParC), sequences of the QRDR of NDM-positive isolates were studied for mutations in gyrA and parC genes. All 6 E. coli isolates carrying NDM had mutations in GyrA at codons 83 (Ser > Leu) and 87 (Asp>Asn) as well as in ParC at codon 80 (Ser > Ile). An additional mutation in ParC was present at codon 88 (Leu > Gln) in one isolate and at codon 84(Glu > Val) in two isolates which were clonally indistinguishable (EN5132, EN5141) (Fig. 2a).

Genetic relatedness, the presence of PMQRs and chromosomal mutations and MIC values of meropenem and ciprofloxacin in NDM-positive (a) E. coli and (b) K. pneumoniae isolates. Analysis of PFGE of XbaI digestion pattern based on Dice’s similarity co-efficient and UPGMA (the position tolerance and optimization were set at 1.5 and 1.5% respectively). More than 95% similarity in PFGE band pattern interpreted as indistinguishable. MEM: meropenem, CIP: ciprofloxacin

K. pneumoniae isolates possessed varied mutations: Ser83Phe and Asp87Ala in GyrA along with Ser80Ile in ParC (n = 10); Ser83Ile mutation in GyrA and Ser80Ile ParC (n = 4) and Ser83Tyr mutation only in GyrA (n = 8). Five isolates had no mutation in the QRDR region (Fig. 2b). The Enterobacter aerogenes isolate possessed no mutation in GyrA or ParC.

In general, isolates accumulating mutations in both GyrA and ParC had higher MIC values (> 32 mg/L) than isolates possessing mutations in only GyrA (1.5–32 mg/L) (Fig. 2a and b).

Analysis of the interplay between chromosomal mutations and PMQRs and its effect on the MIC of ciprofloxacin is represented in Fig. 2b. Four K. pneumoniae isolates (EN5129, EN5135, EN5142, and EN5181) which had acquired PMQRs but lacked QRDR mutations were non-susceptible to ciprofloxacin according to CLSI criteria. Their MIC values were 12, 6, 2, and 14. Whereas one isolate (EN5123) which lacked both PMQRs and mutation in QRDR had a very low MIC (0.094 mg/L). Enterobacter aerogens [EN5131] also lacked the chromosomal mutations but carried PMQRs (aac(6′)-Ib-cr and qnrB) and MIC against ciprofloxacin was 4 mg/L. Overall, 82% NDM-positive isolates possessed GyrA and/or ParC mutation.

Transfer of resistance genes by conjugation / transformation assays and characterization of plasmids

Genetic transference of blaNDM and PMQRs was studied by conjugation (n = 28) or transformation (n = 5) assays. Out of the 29 isolates co-harbouring PMQRs and blaNDM, 12 (41%) isolates including E. coli and K. pneumoniae co-transferred the resistance markers in large plasmids. Aac(6′)-Ib-cr co-transferred with blaNDM in 18% (5/28) isolates which co-harboured the genes. Similarly, qnrB co-transferred with blaNDM in 47% (9/19) cases. One of the two isolates co-harbouring qnrS transferred the gene along with blaNDM. One isolate [EN5129] possessed both blaNDM and PMQRs but did not transfer the blaNDM gene. Detailed molecular characteristics of these isolates and their transconjugants/transformants are presented in Tables 4 and 5. An analysis of the transconjugants of E. coli and K. pneumoniae is presented below separately.

All blaNDM-positive E. coli isolates (n = 6) carried multiple plasmids and were able to conjugally transfer their plasmid(s) carrying blaNDM in selective plates containing cefoxitin (10 mg/L) and sodium azide (100 mg/L) but no transconjugants in ciprofloxacin (0.06 mg/L) and sodium azide (100 mg/L) plates. Among these, 3 possessed aac(6′)-Ib-cr but only in one case this gene co-transferred with blaNDM in a single large 212 kb IncA/C type plasmid which also carried IntI1 and various other resistance genes (blaCTX-M, blaTEM, blaOXA, armA). In other blaNDM-positive E. coli isolates that did not possess PMQRs, blaNDM-harbouring plasmids were of varied replicon types such as IncFII, IncFIIS, IncHIB-M, IncI1A, IncF1A, and IncFIB. Study of the upstream region of blaNDM revealed that 4 carried the complete ISAba125 and 2 carried a truncated version of it. One isolate [EN5169] possessed IS5 element followed by a truncated ISAba125 in the upstream region. bleMBL was present in the downstream region of blaNDM in all E. coli isolates (Fig. 3).

Twenty-six of 27 blaNDM-1-positive K. pneumoniae successfully transferred this gene either through conjugation (n = 22) or transformation (n = 4). Ninety-three percent (25/27) K. pneumoniae isolates co-harboured blaNDM and at least one of the PMQRs. Among these, 11 K. pneumoniae yielded transconjugants co-harbouring blaNDM and PMQRs. On analysis of the transconjugants, it was revealed that 10 of these isolates co-transferred the blaNDM-1 and PMQR genes in single large plasmids of IncFIIK, IncA/C and IncN type. It was noted that 8 of the 10 isolates co-transferring the genes on an IncFIIK plasmid were clonal (indistinguishable PFGE pattern) and this particular clone was isolated from the neonates between 2013 September to 2014 June (Table 4, Fig. 2b). Isolate EN5174 transferred both blaNDM-1 and PMQRs but multiple plasmids were isolated from the transconjugant. Hence, it was hard to determine whether PMQRs co-transferred with blaNDM-1 in a single plasmid or not. However, one isolate (EN5175) yielded different transconjugants on cefoxitin-sodium azide and ciprofloxacin-sodium azide plates. EN5175.T1 (selected on cefoxitin-sodium azide plate) harboured blaNDM-1 in an IncHIB-M plasmid whereas EN5175.T2 (selected on ciprofloxacin-sodium azide plate) harboured qnrB in IncFIIK or IncN plasmid. This showed that blaNDM and qnrB were carried on different plasmids. Rest of the K. pneumoniae isolates (n = 14) only transferred blaNDM in plasmids of type IncHIB-M (n = 8), IncA/C (n = 2), IncFIIK (n = 1) and untypable (n = 3). One K. pneumoniae did not transfer blaNDM via conjugation or transformation.

Out of 27 K. pneumoniae isolates, 20 isolates had ISAba125 upstream blaNDM-1, either complete (1/16) or truncated (15/16). Isolate EN5181 possessed IS630 transposase, isolate EN5127 possessed ISKpn26 transposase, and isolates EN5135 and EN5174 possessed IS5 element followed by a truncated ISAba125 upstream blaNDM-1. The upstream region of 7 isolates could not be determined. All of the K. pneumoniae isolates had a bleMBL gene which confers resistance to bleomycin in the downstream region of the blaNDM gene (Fig. 3).

The Enterobacter aerogenes isolate acquired PMQRs but they were not transferred along with blaNDM-1 through transformation. This isolate carried a truncated ISAba125 in the upstream region and bleMBLgene in the downstream region. Various other resistance determinants (β-lactamases and 16 rRNA methylases) were transferred along with blaNDM in all the organisms studied (Table 4).

Among the plasmid addiction systems found (pndC/A, pemKI, ccdA/B, hok-sok, srnB/C, vagC/D,) only pndC/A was present in a plasmid which carried blaNDM-1 in one case.

Clonality of NDM-possessing E. coli and K. pneumoniae isolates

NDM-possessing E. coli isolates (n = 6) were predominantly diverse except for 2 isolates which were indistinguishable [cluster H (EN5132, EN5141] (Fig. 2a). However, in case of K. pneumoniae, 3 clonal clusters [cluster I (EN5136, EN5137, EN5139), cluster J (EN5150, EN5151, EN5163, EN5165, EN5166, EN5170, EN5173, EN5185) and cluster K (EN5114, EN5117)] were identified and the rest were diverse. (Fig. 2b). Many identical isolates expressed different genotypic characteristics (Fig. 2, Tables 4 and 5).

Discussion

The spread of antimicrobial resistance is primarily caused by the dissemination of large plasmids carrying multiple antibiotic resistance genes [6]. Antibiotic-resistant genes, such as blaNDM-1, are plasmid mediated and often co-harboured with different antibiotic resistance markers such as ESBL genes, aminoglycoside resistance markers and PMQRs [5]. PMQRs do not confer high-level resistance to fluoroquinolones, however, their presence in clinical isolates is of concern as it increases the risk of selecting mutations in gyrase and topoisomerase genes which results in high-level resistance [3]. With the increasing use of fluoroquinolones both in hospital settings and the community, PMQRs can be a palpable threat. In addition to this is the escalating presence of genes such as blaNDM-1 which can facilitate the spread of other plasmid-mediated genes as they may be present in the same plasmid or integrons. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study which compares NDM-positive and NDM-negative Enterobacteriaceae isolates with respect to fluoroquinolone non-susceptibility and prevalence of PMQRs.

In the studied isolates, fluoroquinolone non-susceptibility was very high (90%). Other studies from India also show a very high rate of non-susceptibility to ciprofloxacin [30, 31]. A recent report from India shows that ciprofloxacin resistance was 15% at Day 1 and 38% in Day 60 in the gut flora of antibiotic naïve and exclusively breastfed neonates [32]. For treatment of neonatal infections, fluoroquinolones are used only as salvage therapy [7]. The high prevalence of fluoroquinolone resistance observed in the study is probably a reflection of the high usage of fluoroquinolones to treat other infections such as urinary tract infections (UTI) [32], as this drug used to be sold in India over the counter without prescription before 2014 [33]. It is also known that the mother’s vaginal flora may be a cause of sepsis (particularly early onset, the onset of sepsis within 72 h of birth) and mothers may be already harbouring such resistant organisms [34].

Forty-seven percent (34/73) of the isolates were NDM-positive. Majority of these possessed blaNDM-1 but isolates harbouring blaNDM-5, blaNDM-7, and a novel variant blaNDM-15 were also detected. The prevalence of blaNDM-1 is high in India [35, 36] and blaNDM variants have also been reported [37].

NDM-positive isolates exhibited a higher percentage (97%) of non-susceptibility towards ciprofloxacin than NDM-negative (85%) but the difference was not statistically significant. In this study, a significant number of isolates (81%) carried at least one of the PMQRs. Analysis of the data also revealed that the prevalence of aac(6′)-Ib-cr was highest (71%) followed by qnrB (51%) and qnrS (3%). Earlier studies also support that aac(6′)-Ib-cr is the most prevalent PMQR in India [30, 38]. Although there are currently 81 variants of qnrB and 14 variants of qnrS according to https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA313047 [39], we have exclusively found only qnrB1 and qnrS1. The prevalence of aac(6′)-Ib-cr was significantly higher in K. pneumoniae than E. coli. qnrB and qnrS were absent in E. coli. The higher prevalence of PMQRs in K. pneumoniae compared to E. coli can be the result of the presence of more clonal isolates of K. pneumoniae than E. coli. The prevalence of OqxAB was quite high as they are mostly chromosomally located in K. pneumoniae [29].

Co-occurrence of PMQRs and blaNDM were reported in many earlier studies [5, 6, 21]. In this study, 40% (29/73) isolates co-harboured NDM and PMQRs. Although the prevalence of aac(6′)-Ib-cr, qnrB, and qnrS were generally higher in NDM-positive isolates than NDM-negative isolates the difference was not statistically significant. Hence, probably the spread of PMQRs is not dependent on the blaNDM spread. The higher prevalence of PMQRs (81%) per se in comparison to NDM (47%) is also indicative of this. The occurrence of PMQRs along with β-lactamases has also been reported in several studies [6, 40]. It is to be noted that β-lactamases are highly prevalent in the study isolates and could have contributed to the spread of PMQRs.

Co-transfer of PMQRs along with blaNDM in single large plasmids co-harbouring many other resistance genes have been shown in other studies [6, 21, 27]. The transfer of blaNDM along with qnrB, qnrS, aac(6′)-Ib-cr and various other resistance markers (16S rRNA methylases and other β-lactamases genes) were studied. This study showed that of the 29 isolates which co-harboured NDM and PMQRs, only 12 isolates showed co-transmission of these genes which indicates that not all isolates possessing PMQRs co-transferred the gene with blaNDM because of their probable location on different plasmids.

Worldwide studies on the plasmid types show that IncFII, IncN, IncL/M, IncHIB-M/IncFIB-M, IncA/C, and untypable plasmids carry blaNDM [21]. PMQRs are associated with IncN, IncL/M, IncFII, IncHI1, IncI1, IncR, colE type plasmids [41]. In this study, we have found that in K. pneumoniae, plasmids carrying both blaNDM and PMQRs were of replicon type IncFIIK followed by IncA/C and IncN. IncF group plasmids are highly conjugative and are widely distributed in Enterobacteriaceae [41] and presence of any gene in this group of plasmids will only escalate its spread to other organisms. However, plasmid type IncHIB-M or an untypable plasmid was mostly associated with plasmids carrying blaNDM but not any of the PMQRs. However, in E. coli, there were varied plasmid types, no particular type of plasmid predominated.

Fluoroquinolone resistance in Enterobacteriaceae is also caused by the accumulation of mutations, primarily in DNA gyrase (GyrA), and then in topoisomerase IV [3]. In our study, most NDM-positive isolates exhibited mutations in the QRDR region of GyrA and ParC. All of these mutations were reported earlier in various studies [42]. Four K. pneumoniae isolate and one Enterobacter cloacae carried PMQRs but lacked mutations in the QRDR region of GyrA and ParC, yet the isolates exhibited non-susceptible MIC values against ciprofloxacin. This indirectly points to the well-studied phenomenon that in the absence of chromosomal mutations PMQRs plays an important role in increasing the MIC against ciprofloxacin, thus providing an opportunity to the bacteria to generate chromosomal mutation [3].

Conclusion

This study indicates that fluoroquinolone resistance is high in neonatal septicaemic isolates. PMQRs are highly prevalent, aac(6′)-Ib-cr and qnrB are predominant. Carbapenem resistance in the same set of isolates is primarily due to blaNDM-1. However, we infer that the spread of PMQRs is independent of the spread of blaNDM-1 as the prevalence of PMQRs in non-NDM isolates were nearly similar to the NDM isolates. The possibility of indiscriminate fluoroquinolone use in escalating the spread of blaNDM-1 cannot be ruled out. Co-occurrence of PMQRs with blaNDM in an isolate does not necessarily result in co-transfer of the resistance genes due to their presence mostly in different plasmids. However, the presence of genes such as blaNDM-1and PMQRs shows that the window for treatment options are gradually decreasing and transmissible genes are a threat.

Abbreviations

- NDM:

-

New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase

- PBRT:

-

PCR-based replicon typing

- PFGE:

-

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis

- PMQR:

-

Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance

- QRDR:

-

Quinolone resistance determining region

References

WHO. Critically Important Antimicrobials for Human Medicine; 2017. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

Oliphant CM, Green GM. Quinolones: a comprehensive review. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:455–64.

Rodríguez-Martínez JM, Machuca J, Cano ME, Calvo J, Martínez-Martínez L, Pascual A. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance: two decades on. Drug Resist Updat. 2016;29:13–29.

Nordmann P, Poirel L, Walsh TR, Livermore DM. The emerging NDM carbapenemases. Trends Microbiol. 2011;19:588–95.

Bush K. Carbapenemases: partners in crime. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2013;1:7–16.

Carattoli A. Plasmids and the spread of resistance. Int J Med Microbiol. 2013;303:298–304.

Kaguelidou F, Turner MA, Choonara I, Jacqz-Aigrain E. Ciprofloxacin use in neonates: a systematic review of the literature. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:29–37.

Roy S, Viswanathan R, Singh AK, Das P, Basu S. Sepsis in neonates due to imipenemresistant Klebsiella pneumoniae producing NDM-1 in India. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:1411–3.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty-fourth informational supplement. 2014.

European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters v 3.1, 2013.

Ellington MJ, Kistler J, Livermore DM, Woodford N. Multiplex PCR for rapid detection of genes encoding acquired metallo-β-lactamases. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59:321–2.

Woodford N, Tierno PM Jr, Young K, Tysall L, Palepou MF, Ward E, Painter RE, Sube DF, Shungu D, Silver LL, Inglima K, Kornblum J, Livermore DM. Outbreak of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing a new carbapenem-hydrolyzing class a β-lactamase, KPC-3, in a New York medical center. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:4793–9.

Poirel L, Héritier C, Tolün V, Nordmann P. Emergence of oxacillinase-mediated resistance to imipenem in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:15–22.

Saladin M, Cao VTB, Lambert T, Donay JL, Herrmann JL, Ould-Hocine Z, et al. Diversity of CTX-M β-lactamases and their promoter regions from Enterobacteriaceae isolated in three Parisian hospitals. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;209:161–8.

Colom K, Pérez J, Alonso R, Fernández-Aranguiz A, Lariño E, Cisterna R. Simple and reliable multiplex PCR assay for detection of blaTEM, blaSHVand blaOXA-1genes in Enterobacteriaceae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;223:147–51.

Hong BK, Chi HP, Chung JK, Kim EC, Jacoby GA, Hooper DC. Prevalence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants over a 9-year period. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:639–45.

Espinal P, Fugazza G, López Y, Kasma M, Lerman Y, Malhotra-Kumar S, et al. Dissemination of an NDM-2-producing Acinetobacter baumannii clone in an Israeli rehabilitation center. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:5396–8.

Wang D, Wang H, Qi Y, Liang Y, Zhang J, Yu L. Novel variants of the qnrB gene, qnrB31 and qnrB32, in Klebsiella pneumonia. J Med Microbiol. 2011;60:1849–52.

Everett MJ, Jin YUF, Ricci V, Piddock LJV. Contributions of individual mechanisms to fluoroquinolone resistance in 36 Escherichia coli strains isolated from humans and. Animals. 1996;40:2380–6.

Tenover FC, Arbeit RD, Goering RV, Mickelsen PA, Murray BE, Persing DH, et al. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–9.

Poirel L, Dortet L, Bernabeu S, Nordmann P. Genetic features of blaNDM-1-positive Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:5403–7.

Ruiz del Castillo B, García de la Fuente C, Agüero J, Oteo J, Gómez-Ullate J, Bautista V, et al. Escherichia coli resistant to quinolones in a neonatal unit. J Med Microbiol. 2011;60:1713–6.

Berçot B, Poirel L, Nordmann P. Plasmid-mediated 16S rRNA methylases among extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:4526–7.

Kado CI, Liu ST. Rapid procedure for detection and isolation of large and small plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:1365–73.

Mnif B, Vimont S, Boyd A, Bourit E, Picard B, Branger C, et al. Molecular characterization of addiction systems of plasmids encoding extended-spectrum-β-lactamases in Escherichia coli. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:1599–603.

Shibata N, Doi Y, Yamane K, Kurokawa H, Shibayama K, Kato H, et al. PCR typing of genetic determinants for Metallo- β -lactamases and integrases carried by gram-negative Bacteria isolated in Japan , with focus on the class 3 Integron PCR typing of genetic determinants for Metallo-β-lactamases and integrases carried by. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5407–13.

Datta S, Mitra S, Chattopadhyay P, Som T, Mukherjee S, Basu S. Spread and exchange of bla NDM-1 in hospitalized neonates: role of mobilizable genetic elements. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36:255–65.

Chatterjee S, Datta S, Roy S, Ramanan L, Saha A, Viswanathan R, et al. Carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii and other acinetobacter spp. causing neonatal sepsis: focus on NDM-1 and its linkage to ISAba125. Front Microbiol. 2016. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01126.

Rodríguez-Martínez JM, de Alba PD, Briales A, Machuca J, Lossa M, Fernández-Cuenca F, et al. Contribution of OqxAB efflux pumps to quinolone resistance in extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:68–73.

Yugendran T, Harish BN. High incidence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance genes among ciprofloxacin-resistant clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae at a tertiary care hospital in Puducherry. India PeerJ. 2016;4:e1995.

Tripathi A, Kumar S. High prevalence and significant association of ESBL and QNR genes in pathogenic Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates of patients from Kolkata. India. 2012;52:557–64.

Saksena R, Gaind R, Sinha A, Kothari C, Chellani H, Deb M. High prevalence of fluoroquinolone resistance amongst commensal flora of antibiotic naïve neonates: a study from India. J Med Microbiol. 2018;67:481–8.

Laxminarayan R, Chaudhury RR. Antibiotic resistance in India: drivers and opportunities for action. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1001974.

Zaidi AKM, Huskins WC, Thaver D, Bhutta ZA, Abbas Z, Goldmann DA. Hospital-acquired neonatal infections in developing countries. Lancet. 2005;365:1175–88.

Walsh TR, Weeks J, Livermore DM, Toleman MA. Dissemination of NDM-1 positive bacteria in the New Delhi environment and its implications for human health: an environmental point prevalence study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:355–62.

Datta S, Roy S, Chatterjee S, Saha A, Sen B, Pal T, et al. A five-year experience of carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae causing neonatal septicaemia: predominance of NDM-1. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112101.

Ahmad N, Ali SM, Khan AU. Detection of New Delhi Metallo-β-lactamase variants NDM-4, NDM-5, and NDM-7 in Enterobacter aerogenes isolated from a neonatal intensive care unit of a North India hospital: a first report. Microb Drug Resist. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1089/mdr.2017.0038.

Bhattacharya D, Bhattacharjee H, Thamizhmani R, Sayi DS, Bharadwaj AP, Singhania M, et al. Prevalence of the plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants among clinical isolates of Shigella sp. in Andaman & Nicobar Islands, India. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2011;53:247–51.

NCBI Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance Reference Gene Database. 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA313047. Accessed 25 Feb 2019.

Freeman JT, Rubin J, McAuliffe GN, Peirano G, Roberts SA, Drinković D, et al. Differences in risk-factor profiles between patients with ESBL-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae: a multicentre case-case comparison study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2014;3:1–7.

Carattoli A. Resistance plasmid families in Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:2227–38.

Ruiz J. Mechanisms of resistance to quinolones: target alterations, decreased accumulation and DNA gyrase protection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51:1109–17.

Acknowledgments

We extend our thanks to George A. Jacoby for providing PCR controls. We also thank the staff of the Department of Neonatology, SSKM Hospital, who cared for the neonates included in the study and Mr. Subhadeep De for his laboratory assistance.

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Funding

The study was supported by Department of Science and Technology, West Bengal extramural funding and Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) intramural funding. S. M and S. N were recipients of Senior Research Fellowship from Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, India and Junior Research Fellowship from the Department of Science and Technology, West Bengal respectively.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article and its Additional file 1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: SB, Performed the experiments: SM1, SN. Analysed the data: SM1, SM2, SD, SB. Contributed reagents/ materials/analysis tools: SD, SB, SM2, PC. Contributed to the writing of the manuscript: SM1, SB and SD. Coordinated collection of specimens, maintenance of clinical data: SM2, PC. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was carefully reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the ICMR-National Institute of Cholera and Enteric Diseases (Indian Council of Medical Research) (No. A-1/2015-IEC, dated 31st August 2015).

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Detailed information of all studied Enterobacteriaceae : MIC values of meropenem and cirpfloxacin, antibiotic susceptibility pattern and distribution of different resistance genes. (XLSX 28 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mitra, S., Mukherjee, S., Naha, S. et al. Evaluation of co-transfer of plasmid-mediated fluoroquinolone resistance genes and blaNDM gene in Enterobacteriaceae causing neonatal septicaemia. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 8, 46 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-019-0477-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-019-0477-7