Abstract

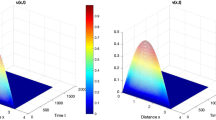

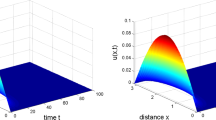

In this paper, we are concerned with a homogeneous reaction–diffusion Atkinson oscillator system subject to homogeneous Neumann boundary conditions on a bounded spatial domain. Using the comparison principle and the techniques of invariant rectangle, we prove the existence of the attraction region of the solutions. We thus prove that under certain conditions, the solutions of the PDE system converge to the unique positive equilibrium solutions. We also derive precise conditions such that the system does not have nonconstant positive steady-state solutions. Finally, we use the bifurcation technique to show the existence of Turing patterns. The results provide a clearer understanding of the mechanism of formations of patterns.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In 1952, Turing [1] proposed a famous idea of “diffusion-induced instability,” which says that the destabilization of otherwise stable constant steady state will lead to the emergence of stable nonuniform spatial structures, which are usually called Turing patterns. Over the years, Turing’s idea has attracted the attention of a great number of investigators and was successfully developed on theoretical backgrounds. In 1990, De Kepper et al. [2, 3] discovered the formation of stationary three-dimensional (but almost two-dimensional) structures with characteristic wavelengths of 0.2 mm, which is the first experimental evidence to the Turing patterns nearly 40 years after the publication of [1]. Since then, the research of Turing patterns in chemistry has sprung up (see [4–13] and the references therein).

In this paper, we are concerned with the pattern formations of a kind of diffusive Atkinson oscillator model, which is used to characterize the mechanism of pattern formations of the oscillators [14]:

To analyze the generation mechanism of periodic solutions, it is assumed that RNA transcripts are fast process, that is, we assume that \(dw/dt =ds/dt=0\). Then the system can be simplified to the second-order planar system:

Since the chemical reaction obeys a diffusion process, it is natural to add diffusion to the model (1.1), which leads to the following reaction–diffusion system:

The model has been studied extensively by several authors, but most of the research focuses on the corresponding ODE system (1.1). To the best of knowledge, there are few works in the existing literature studying the dynamical behavior and bifurcations of the corresponding reaction–diffusion equations. In this paper, we attempt to study the Atkinson PDE model. We are concerned with the global existence, boundedness of time-independent solutions, the asymptotical behavior of the constant steady states, and the bifurcations from the positive steady-state solutions. In particular, we derive precise conditions under which system (1.2) does not have Turing patterns.

This paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we study the boundedness and uniqueness of global-in-time solutions of system (1.2). In particular, we show that there exists an invariant rectangle that attracts all the solutions of system (1.2) regardless of the initial values. Then, we consider the long-time behavior of the solutions of system (1.2) and derive precise conditions under which the solutions converge exponentially to a unique constant steady-state solution. In Section 3, we derive conditions under which system (1.2) has no nonconstant positive steady states, including Turing patterns. In Section 4, we use global bifurcation theory to prove the existence of Turing patterns.

2 Global existence, boundedness, and asymptotical behavior of solutions

In this section, we consider the global existence, boundedness, and asymptotical behavior of the solutions. To begin with, it is clear that system (1.2) has a unique positive steady-state solution \((u_{*},v_{*})\) of the system

We have the following results on the global existence and boundedness of the time-dependent solutions of system (1.2).

Proposition 2.1

Suppose that \(a,\alpha_{1},\alpha_{2},\lambda _{1},\lambda_{2}>0\). For any \(d_{1},d_{2}>0\), the initial boundary value problem (1.2) admits a unique solution \((u(x,t),v(x,t))\) for all \(x\in\Omega\) and \(t>0\). Moreover, there exist two positive constants \(M_{1}\) and \(M_{2}\), depending on \(\alpha_{1},\alpha_{2},\lambda_{1},\lambda_{2}\), \(u_{0}(x)\), and \(v_{0}(x)\), such that

Proof

The existence and uniqueness of local-in-time solutions to the initial-boundary value problem (1.2) is well known [15].

For the global existence and the boundedness of the solutions, we partially use the techniques of invariant region [10, 11, 16]. A region \(\Re:=[U_{1},U_{2}]\times[V_{1},V_{2}]\) in the \((u,v)\) phase plane is called a positively invariant region of system (1.2) if the vector field

points inward on the boundary of ℜ for all \(t\geq0\). We construct the invariant rectangle \(\Re:=[U_{1},U_{2}]\times[V_{1},V_{2}]\) in the following way:

Obviously, \(u_{0}(x)\) and \(v_{0}(x)\) are closed by the rectangle ℜ. Now we prove that the vector field points inward on the boundary of ℜ.

On \(u=U_{1},V_{1} \leq v \leq V_{2}\), by the definition of \(U_{1}\) we have

On \(u=U_{2},V_{1} \leq v \leq V_{2}\), by the definition of \(U_{2}\) we have

On \(v=V_{1},U_{1} \leq u \leq U_{2}\), by the definition of \(V_{1}\) we have

On \(v=V_{2},U_{1} \leq u \leq U_{2}\), by the definition of \(V_{2}\) we have

Thus, \(\Re:=[U_{1},U_{2}]\times[V_{1},V_{2}]\) is an invariant rectangle for the vector field, where \(M_{1}:=\min\{U_{1},V_{1}\}\) and \(M_{2}:=\max\{ U_{2},V_{2}\}\). □

We now prove that system (1.2) has an attraction region, which in fact attracts all solutions of the system, regardless of the initial values [17].

Theorem 2.2

Suppose that \((u(x,t),v(x,t))\) is the unique solution of system (1.2). For any \(x\in\overline{\Omega}\), we have:

Proof

(a). Let us prove that \(\lambda_{1}<\lim\inf_{t\rightarrow\infty }u\). By Proposition 2.1 there exists a sufficiently small number \(0<\varepsilon<\lambda_{1}\alpha _{1}{v^{n_{1}}}/(1+v^{n_{1}})\) for all \(x\in\overline{\Omega}\) and \(t>0\). Let \(u_{1}\) be the unique solution of the following ODE:

Setting \(\rho_{1}(x,t)=u(x,t)-u_{1}(t)\), we have

By the maximum principle for parabolic equations, we have \(\rho_{1}(x,t) > 0\), which means that \(u(x,t)>u_{1}(t)\) for all \(x\in\overline{\Omega}\) and \(t>0\). From (2.6) we have \(\lim_{t\rightarrow\infty}{u_{1}(t)}=\lambda _{1}+\varepsilon\).

Thus,

(b). Let us now prove that \(\lim\sup_{t\rightarrow\infty}u<\lambda _{1}(1+\alpha_{1})\). By Proposition 2.1 there exists a sufficiently small number \(0<\eta<\lambda_{1}\alpha _{1}/(1+v^{n_{1}})\) for all \(x\in\overline{\Omega}\) and \(t>0\). Let \(u_{2}\) be the unique solution of the following ODE:

Setting \(\rho_{2}(x,t)=u(x,t)-u_{2}(t)\), we have

By the maximum principle for parabolic equations we have \(\rho_{2}(x,t) < 0\), which means that \(u(x,t)< u_{2}(t)\) for all \(x\in\overline{\Omega}\) and \(t>0\). From (2.9) we have \(\lim_{t\rightarrow\infty}{u_{2}(t)}=\lambda_{1}(1+\alpha _{1})-\eta\).

Thus,

(c). Let us prove that \(\frac{\lambda_{2}}{1+\lambda_{1}(1+\alpha _{1})}<\lim\inf_{t\rightarrow\infty}v\). By Proposition 2.1 there exists a sufficiently small number \(\varphi >0\) such that \(\varphi<(1+\lambda_{1}(1+\alpha_{1}))v\) for all \(x\in\overline{\Omega}\) and \(t>0\). Let \(v_{1}\) be the unique solution of the following ODE:

Setting \(\xi_{1}(x,t)=v(x,t)-v_{1}(t)\), we have

By the maximum principle for parabolic equations we have \(\xi_{1}(x,t) > 0\), which means that \(v(x,t)>v_{1}(t)\) for all \(x\in\overline{\Omega}\) and \(t>0\). From (2.12) we have \(\lim_{t\rightarrow\infty}{v_{1}(t)}=\frac{\lambda_{2}+\varphi }{(1+\lambda_{1}(1+\alpha_{1}))}\).

Thus,

(d). Let us prove that \(\lim\sup_{t\rightarrow\infty}v < \frac {\lambda_{2}(1+\alpha_{2})}{1+\lambda_{1}}\). Since

there exists a finite number \(t_{0}\), depending on \((u_{0},v_{0})\), such that, for any \(x\in\overline{\Omega}\) and \(t\geq t_{0}\),

By Proposition 2.1 and (2.16) there exists a sufficiently small number \(\delta>0\) such that, for all \(x\in\overline{\Omega}\) and \(t\geq t_{0}\), we have

Let \(v_{2}\) be the unique solution of the following ODE:

Setting \(\xi_{2}(x,t)=v(x,t)-v_{2}(t)\), by (2.17) and (2.18) we have

By the maximum principle for parabolic equations we have \(\xi_{2}(x,t) < 0\), which means that \(v(x,t)< v_{2}(t)\) for all \(x\in\overline{\Omega}\) and \(t>t_{0}\). From (2.18) we have \(\lim_{t\rightarrow\infty}{v_{2}(t)}=\frac{\lambda_{2}(1+\alpha _{2})-\delta}{1+\lambda_{1}}\).

Thus, we have proved that

□

Next, in the particular case, we derive precise conditions under which \((u_{*},v_{*})\) is a globally asymptotically stable solution of the corresponding ODEs of system (1.2) and that all the solutions of (1.2) tend to \((u_{*},v_{*})\) [18]:

Theorem 2.3

Define

Suppose that \(n_{1}=n_{2}=1\) and that either \(H_{1}<2\) or \(H_{2}>2\). Then, \((u_{*},v_{*})\) is a globally asymptotically stable solution of the corresponding ODEs of system (1.2). If, additionally, \(\max\{1,d\}>M/\lambda_{1}\), then every solution of system (1.2) converges exponentially to the unique constant equilibrium solution \((u_{*},v_{*})\), where \(\mu_{1}\) is the smallest positive eigenvalue of −Δ on Ω subject to homogeneous Neumann boundary conditions, and

Proof

Consider the following ODEs in the particular case \(n_{1}=n_{2}=1\):

The Jacobian matrix \(J(u,v)\) at \((u,v)\) is given by

Then, we have

By (2.5) we have

On the other hand,

If either \(H_{1}<2\) or either \(H_{2}>2\), then we have \(\frac{\partial f}{\partial u}+\frac{\partial g}{\partial v} <0\) (or >0). Hence, the Poincaré–Bendixson theorem implies that \((u_{*},v_{*})\) is globally asymptotically stable in (2.23). Define

By [19], if \(\max\{1,d\}>M/\mu_{1}\), where \(d=\min\{d_{1},d_{2}\}\), then every solution of system (1.2) converges exponentially to the unique constant equilibrium solution \((u_{*},v_{*})\). □

3 Nonexistence of Turing patterns

In this section, for the particular case where both \(n_{1}\) and \(n_{2}\) equal 1, we show the nonexistence of nonconstant positive steady-state solutions of the system

Lemma 3.1

Suppose that \((u(x),v(x))\) is any given positive steady-state solution of system (1.2). For any \(x\in\overline{\Omega}\), we have:

The lemma is the direct consequence of Theorem 2.1 in [17].

For a steady-state solution pair \((u(x),v(x))\) of system (3.1), we define

Lemma 3.1 shows that any positive solution \((u,v)\) of system (3.1) satisfies \((u,v)\in R \), where

Define

We now state the following theorem regarding the nonexistence of a nonconstant positive solution of system (3.1).

Lemma 3.2

Let \(g_{i}(u,v)\) and \(G_{i}\), \(i=1,2,3\), be defined as in (3.5) and (3.7). Suppose that \(d_{1}>\frac{1}{\mu_{1}}\) and \(d_{2}> \frac{\lambda_{2} \alpha_{2} G_{2}}{\mu_{1}}\). Then, we have

Proof

Multiplying the first equation of (3.1) by ϕ and integrating over Ω, we have

By Green’s formula we have

On the other hand, we have

Substituting (3.11) into (3.10), we have

Thus,

Since \(d_{1}>\frac{1}{\mu_{1}}\), we have

Thus,

Multiplying the second equation of (3.1) by ψ and integrating over Ω, we have

Furthermore,

Since \(d_{2}>\frac{\lambda_{2} \alpha_{2} G_{2}}{\mu_{1}}\), we have

Thus,

□

Theorem 3.3

Let \(g_{i}(u,v)\), \(G_{i}\), \(i=1,2,3\), and \(\varphi(x)\) be defined as in (3.5), (3.7), and (3.22). Then, for any \((d_{1},d_{2}) \in\Re\), system (3.1) has no nonconstant positive solutions, where

with

Proof

By Lemma 3.2 we have

For any \((d_{1},d_{2}) \in\Re\), we have \(\frac{\lambda_{1}\lambda_{2}\alpha_{1}G_{1}G_{3}}{(d_{2}\mu _{1}-\lambda_{2}\alpha_{2}G_{2})(d_{1}\mu_{1}-1)}<1\). Thus \(\nabla\psi\equiv0 \). Similarly, we have \(\nabla\phi\equiv0 \). Hence, system (3.1) has no nonconstant positive solutions. □

4 Existence of bifurcating positive nonconstant steady-state solutions

In this section, for the particular case where both \(n_{1}\) and \(n_{2}\) equal 1, we use the global bifurcation theory to prove the existence of positive nonconstant steady state of system (3.1). In particular, we are concerned with the existence of Turing patterns.

The linearized operator of system (2.23) evaluated at equilibrium \((u_{*},v_{*})\) is given by

where

Then the characteristic equation of (4.1) is given by

By (2.1) and (4.3) if follows that if

then \((u_{*},v_{*})\) is positive and stable in the ODEs (2.23); Moreover, if \(\chi_{3}>\frac{1}{\lambda_{2}\alpha_{2}}\), then system (1.2) is a substrate-inhibition system.

The linearized operator of system (3.1) evaluated at \((u_{*},v_{*})\) is given by (choosing \(d_{1}\) as the bifurcation parameter)

Let \(\mu_{i}\) and \(\xi_{i}(x),i \in{\mathcal{N}}_{0}\), be the eigenvalues and the corresponding eigenfunctions of −Δ in Ω subject to Neumann boundary conditions. Then the eigenvalues of \(L(d_{1})\) are given by those of the following operator \(L_{i}(d_{1})\):

the characteristic equation of which is

where

According to [13], if there exist \(i \in{\mathcal{N}}_{0}\) and \(d_{1}*>0\) such that

and \(\frac{d}{dd_{1}}D_{i}(d_{1}*)\neq0\), then a global steady-state bifurcation occurs at the critical point \(d_{1}*\).

By (4.4) we have \(H_{0}(d_{1})<0\). Thus, for all \(i \in{\mathcal {N}}_{0}\), we have \(H_{i}(d_{1})<0\). Solving \(D_{i}(d_{1})= 0\), we get the set of critical values of \((d_{1},d_{2})\) given by the hyperbolic curves \(C_{i}\) with \(i\in{\mathcal{N}}:={\mathcal{N}}_{0} \backslash\{0\}\):

Suppose that \(\mu_{i}\), \(i \in{\mathcal{N}}\), are the simple eigenvalues of −△. Following [20], we call \(B:=\bigcup_{i=1}^{\infty}C_{i}\) the bifurcation set with respect to \((u_{*},v_{*})\) and denote \(B_{0}\) by the countable set of intersection points of two curves of \(\{C_{i}\}_{i=1}^{\infty}\); also denote \(\widehat {B}=B \backslash B_{0}\).

Clearly, for any fixed \(d_{2}>0\), there exists a unique \(d_{1}^{i}\) such that \((d_{1}^{i},d_{2}) \in\widehat{B}\cap C_{i}\), and at \(d=d_{1}^{i}\), both (4.9) and \(\frac{d}{dd_{1}}D_{i}(d_{1}*)\neq0\) are satisfied.

Then, from [13] we have the following results regarding the existence of Turing patterns.

Theorem 4.1

Suppose that (4.4) holds and that \(C_{i}\) is defined in (4.10), where \(\mu_{i}\), \(i \in{\mathcal{N}}\), is the simple eigenvalue of −△. Then, for any \((d_{1}^{i},d_{2}) \in \widehat{B}\cap C_{i}\) with \(d_{2}\) fixed, there is a smooth curve \(\Gamma_{i}\) of positive solutions of (3.1) bifurcating from \((d_{1},u,v)=(d_{1}^{i},u_{*},v_{*})\) with \(\Gamma_{i}\) contained in a global branch \(C_{i}\) of the positive solutions of (3.1). Moreover:

-

1.

Near \((d_{1},u,v)=(d_{1}^{i},u_{*},v_{*})\), \(\Gamma_{i}=\{(d_{1}(s),u(s),v(s):s \in(-\varepsilon,\varepsilon))\}\), where \(u(s)=u_{*}+s\mathbf{a}_{i}\xi _{i}(x)+so_{1}(s),v(s)=v_{*}+s\mathbf{b}_{i}\xi_{i}(x)+so_{2}(s)\) for \(s \in (-\varepsilon,\varepsilon)\) for some \(C^{\infty}\) smooth functions \(d_{1}(s),o_{1}(s),o_{2}(s)\) such that \(d_{1}(0)=d_{1}^{i}\) and \(o_{1}(0)=o_{2}(0)=0\). Here \(\mathbf{a}_{i}\) and \(\mathbf{b}_{i}\) satisfy \(L_{i}(d_{1})(\mathbf {a}_{i},\mathbf{b}_{i})^{T}=(0,0)^{T}\), and \(\xi_{i}(\cdot)\) is the corresponding eigenfunction of the eigenvalue \(\mu_{i}\) of -△.

-

2.

The projection of \(C_{i}\) onto \(d_{1}^{i}\)-axis contains the interval \((0, d_{1}^{i})\).

Proof

By (4.10) it follows that (4.9) holds. Thus, the local steady-state bifurcation occurs near the positive steady-state solution. Then, by Theorem 3.1 in [13] we can conclude that the local steady-state bifurcation branches are actually global. Furthermore, since our model is in the framework of [20], we can induce from Theorem 2.3 of [20] that the bifurcation branch cannot contain another bifurcation point \((d_{1}^{j}, u_{*},v_{*})\), with \(i\neq j\). This completes the proof of the theorem. □

5 Conclusion

In this paper, we considered a class of homogeneous reaction–diffusion Atkinson oscillator system under Neumann boundary conditions. First, we proved the global existence and boundedness of the time-dependent solutions, which converge to the unique positive equilibrium solution under certain conditions. Then we show the nonexistence of nonconstant positive steady-state solutions of the system. Finally, we proved the existence of Turing patterns by using the global steady-state bifurcation theory. To get better results, we have only taken into account the particular case \(n_{1} = n_{2} = 1\). Considering the more general situation is the next step of our research.

Abbreviations

- LacI:

-

Lipoprotein-associated coagulation inhibito

- NRI:

-

nitrogen regulator I

- NRI-P:

-

NRI-phosphate

References

Turing, A.M.: The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B, Biol. Sci. 237, 37–72 (1952)

Castets, V., Dulos, E., Boissonade, J., De Kepper, P.: Experimental evidence of a sustained Turing-type equilibrium chemical pattern. Phys. Rev. Lett. 64, 2953–2956 (1990)

De Kepper, P., Castets, V., Dulos, E., Boissonade, J.: Turing-type chemical patterns in the chlorite–iodide–malonic acid reaction. Physica D 49, 161–169 (1991)

Jang, J., Ni, W., Tang, M.: Global bifurcation and structure of Turing patterns in the 1-D Lengyel–Epstein model. J. Dyn. Differ. Equ. 16, 297–320 (2004)

Judd, S., Silber, M.: Simple and superlattice Turing patterns in reaction–diffusion systems: bifurcation, bistability, and parameter collapse. Physica D 136, 45–65 (2000)

Jin, J., Shi, J., Wei, J., Yi, F.: Bifurcations of patterned solutions in a diffusive Lengyel–Epstein system of CIMA chemical reaction. Rocky Mt. J. Math. 43(4), 1637–1674 (2013)

Epstein, I.R., Pojman, J.A.: An Introduction to Nonlinear Chemical Dynamics. Oxford University Press, Oxford (1998)

Lengyel, I., Epstein, I.R.: Modeling of Turing structures in the chlorite–iodide–malonic acid-starch reaction system. Science 251, 650–652 (1991)

Lengyel, I., Epstein, I.R.: A chemical approach to designing Turing patterns in reaction-diffusion systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 3977–3979 (1992)

Ni, W., Tang, M.: Turing patterns in the Lengyel–Epstein system for the CIMA reactions. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 357, 3953–3969 (2005)

Yi, F., Liu, S., Tuncer, N.: Spatiotemporal patterns of a reaction diffusion substrate-inhibition Seelig model. J. Dyn. Differ. Equ. 29, 219–241 (2017)

Yi, F., Wei, J., Shi, J.: Diffusion-driven instability and bifurcation in the Lengyel–Epstein system. Nonlinear Anal., Real World Appl. 9, 1038–1051 (2008)

Yi, F., Wei, J., Shi, J.: Bifurcation and spatiotemporal patterns in a homogenous diffusive predator–prey system. J. Differ. Equ. 246(5), 1944–1977 (2009)

Atkinson, M.R., Savageau, M.A., Myers, J.T., Ninfa, A.J.: Development of genetic circuitry exhibiting toggle switch or oscillatory behavior in Escherichia coli. Cell 113, 597–607 (2003)

Friedman, A.: Partial Differential Equations of Parabolic Type. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs (1964)

Weinberger, H.F.: Invariant sets for weakly coupled parabolic and elliptic systems. Rend. Mat. 8, 295–310 (1975)

Ghergu, M., Radulescu, V.: Reaction–diffusion systems arising in chemistry. In: Nonlinear PDEs. Mathematical Models in Biology, Chemistry and Population Genetics. Springer Monographs in Mathematics, Springer, New York, pp. 297–298 (2012)

Ghergu, M., Radulescu, V.: Reaction–diffusion systems arising in chemistry. In: Nonlinear PDEs. Mathematical Models in Biology, Chemistry and Population Genetics. Springer Monographs in Mathematics, Springer, New York, pp. 293–295 (2012)

Conway, E., Hoff, D., Smoller, J.: Large time behavior of solutions of systems of nonlinear reaction–diffusion equations. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 35(1), 1–16 (1978)

Nishiura, Y.: Global structure of bifurcating solutions of some reaction diffusion systems. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 13(4), 555–593 (1982)

Acknowledgements

X. Yang was partially supported by Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University from Ministry of Education (NECT-13-0755). Y. Chai was partially supported by Scientific Research Foundation for the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars of Heilongjiang Province (LC2012C36). C. Yu was major supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (61571159).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This research is supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China and National Natural Science Foundation of China (61571159).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, X., Wang, W., Chai, Y. et al. Dynamical behavior and bifurcation analysis of a homogeneous reaction–diffusion Atkinson system. Bound Value Probl 2018, 21 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13661-018-0939-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13661-018-0939-5