Abstract

A new pedagogical methodology is proposed to reduce the social vulnerability of indigenous communities occupying areas subject to volcanic activity, as a potential interactive approach between those communities, scientists, and scientific institutions. The multidisciplinary methodology aims to increase scientist’s understanding of the relationship between native inhabitants and active volcanoes in indigenous territories, and to improve the effective dissemination of information. Also, the proposed methodology offers to the local community the scientific knowledge in an understandable and useful way, in order to maximize people’s awareness of their exposure to volcanic activity. The procedure starts with the recognition of the local ancestral comprehension of the volcano and the cultural, ecological, and economical bonds between humans and volcanic processes. Subsequently, the transmission of the indigenous knowledge to the scientific community and the appropriation of geological knowledge by the children and teachers in a specific Māori primary school in New Zealand, allowed: (1) the establishment of a common language, (2) enhanced communication and collaboration between the participants involved in understanding and living with an active volcano, and (3) increased awareness about the relationship between humans and active volcanoes.

A permanent application (and site-specific adjustment) of this method, and the use of the resulting teaching tools, could reduce social vulnerability and empower indigenous communities in the development of volcanic risk mitigation strategies by revitalizing and sharing knowledge, rather than imposing one epistemological system onto the other.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction background

The lack of dialogue among stakeholders undertaking volcanic risk management hinders agreement in front of decision-making processes (cf., King et al. 2007). The scarcity of programs that integrate scientific-knowledge with the local epistemology, including the environmental and cultural relationship between the community exposed to volcanic eruptions and the volcano itself, is a key factor increasing the social vulnerability (cf., Alexander 1993, Paton et al. 2001, Paton et al. 2008, Vervaeck 2012). This is critical in the case of lands occupied by indigenous communities where the relationship between people and territory is long and more complex than a simple land occupation for resource management (cf., Marsden 1988, 1992).

In most of the indigenous communities worldwide, the territory is the centre of their identity, culture, livelihood practices, ecology, economy, and knowledge and belief systems (cf., Feiring 2013). Therefore, the concept of territory is usually closest to the scientific notion of “ecosystem” than to the western concept of “land”. However, it differs in that the perception of the territory by most indigenous people is also based on the idea that everything in the environment has life and spirit (cf., Berkers et al. 1998). Although spirituality has been traditionally excluded from any scientific approach, Anderson (1996) pointed out that “all traditional societies that have succeeded in managing resources well, over time, have done it in part through religious or ritual representation of resource management. The key is not religion per se, but the use of emotionally powerful cultural symbols to sell particular moral codes and management systems”.

The value of traditional knowledge in sustainable development and ecosystem management, biodiversity conservation, and climate change adaptation has been increasingly recognized by the western knowledge (scientific) systems (Feiring 2013). In Oceania cultures (including Polynesians), Berkers et al. (1998) identified one of the richest set of ecosystem applications, where the key characteristics defining the territory as an ecosystem-like unit are: (1) a unit with the height of land between adjacent valleys serving as the biophysical boundary; (2) the recognition of land and sea space as a continuum; (3) the presence of a social and ethical mechanism for integrating humans and nature, where elders and leaders encourage the responsibility for the land within a system of conservation-through-use. Within these concepts, western science increasingly acknowledges indigenous understanding of the non-linearity and openness of the natural ecosystems, which are not always predictable and, certainly, not always controllable (cf., Gunderson et al. 1995, Ludwig et al. 1993). Moreover, the criteria of territory delimitation in many traditional cultures worldwide are watershed-based, which has been interpreted by Berkers et al. (1998) as a mirror of their dependence on local resources.

Understanding the local indigenous vision about nature, as well as the cultural and environmental links with the territory is critical, not only for the development of conservation strategies (e.g., Stevenson 1996), but also for hazard mitigation and risk management (cf., King et al. 2007; Cronin and Cashman 2008). For example, King et al. (2008) postulated how Māori Environmental knowledge in New Zealand provides a collection of observations, records, monitoring and forecast methods of changes in their physical environment that contribute to hazard mitigation. Likewise, Lowe et al. (2002) demonstrated how Māori oral history of volcanic eruptions were a valuable source of information, not only on past eruption records, but also, on the understanding of past response and recovery of Māori tribes to volcanic hazards. Similarly, King et al. (2008) carried on an extensive approach on how Māori oral narratives, laments, quotations, proverbs, songs, and place names relate with natural hazards and have served to teach, preserve, and explain their occurrence. The importance of oral tradition for volcanological investigations has been also demonstrated in other Polynesian islands, such as Hawaii (cf., Swanson 2008).

This study aims to contribute to the development of hazard mitigation strategies by reducing the social vulnerability of indigenous communities exposed to volcanic eruptions through recognition of their traditional knowledge and its integration with the geological understanding of the world. The feedback between different, but not necessarily exclusive epistemological systems combines multiple sources of expertise and enhances communication between the variable participants in volcanic risk management (e.g., scientists, local communities, extendable to governmental agencies such as geological surveys). Rather than “imposing” western science onto indigenous communities living around active volcanoes we propose a participative dialogue in order to maximize the local awareness and build up a strategy derived from multiple disciplines for risk mitigation. The methodology was developed in collaboration with and applied within the native Māori tribe Ngāti Rangi Iwi, in the North Island of Aotearoa (New Zealand), inhabiting the influence zones of Mt. Ruapehu (Figure 1) volcanic activity.

Location map of Mt. Ruapehu at the southernmost end of the Taupo Volcanic Zone (TVZ) in the North Island of New Zealand (Te Ika ā Māui). The general view of the North Island (a) is based on the map provided by http://prosale.co.nz/html/map.html, where the location of Mt. Taranaki can be seen, offset from the Tongariro Volcanic Centre (green square); the latter, comprising Mt. Ruapehu, Mt. Tongariro, and Pihanga volcanoes is shown in (b), based on a STER GDEM, 30 m resolution DEM. The coordinates are UTM.

Indigenous knowledge in the New Zealand context is termed “mātauranga māori”, and for this project would specifically be referred to as “mātauranga a Nāti Rangi”, referred to hereafter as mātauranga. Here, we will show how the body language (dance and other non-verbal forms clarified below, in the methodology chapter), in combination with other expressive forms (verbal language, writing, drawing) is a useful tool to bridge mātauranga and earth sciences. The integration of mātauranga, science, and arts served to (1) communicate the current understanding of geological and volcanological processes from multiple perspectives; (2) empower indigenous communities living on active volcanoes to increase their awareness; (3) develop a teaching tool for current and future generations, which can be used at different levels within the community. Furthermore, this method follows an adaptive management approach that allows iterative amendments, to ensure the tool remains relevant as societies and volcanoes change through time.

Mt. Ruapehu volcano geological context

Mt. Ruapehu is one of the most active stratovolcanoes of New Zealand (Cronin and Neall 1997). Located at the southern end of the Taupo Volcanic Zone, it has erupted low-K andesitic-dacitic magmas in effusive and explosive (from phreatic to Plinian) eruptions since ~270 ka (Donoghue et al. 1995, Pardo et al. 2012). The main edifice is asymmetrical; it comprises lava-flows, rare domes, and has been affected by events of sector collapse (cf., Palmer and Neall 1989, McClelland and Erwin 2003, Procter et al. 2010, Tost et al. 2014). The volcano is capped by small permanent glaciers and snowfields and comprises overlapping craters (Hackett and Houghton 1989, Cronin et al. 1996). Historical activity has been centred at the youngest South Crater, currently occupied by an acidic Crater Lake (Christenson and Wood 1993), from which lahar generation is common (e.g. Cronin and Neall 1997, Neall et al. 2001, Lube et al. 2009). Holocene eruptions have been predominantly phreatic, producing base surges and ballistic fallout, and phreatomagmatic, producing subplinian columns (Cronin et al. 1997, Kilgour et al. 2010).

Ngāti Rangi Iwi

“Whaia e au Manganui-o-te-ao kia tau au ki runga ō Ruapehu ki Ngā Turi ō Murimotu ko te Ahi-kā o Paerangi-i-te-Whare-Toka i puta mai ai Rangituhia, Rangiteauria me Uēnuku-Manawa-Wiri”. [Translates “I follow the Manganui o tea o river, I settle up on Ruapehu and the sacred alter of Nga Turi o Murimotu, the eternal flame of Paerangi, from hence we originate. Paerangi begat Rangituhia, Rangiteauria, and their sister Ueunuku Manawa Wiri”]. This is how Ngāti Rangi people introduce themselves, and intrinsically links their ancestry to the land, its geomorphology, and the flowing waters

The Ngāti Rangi Iwi falls under the mantle of Te Kāhui Maungā an identity, which encompasses the mountains of the district and its original inhabitants. The ancestors of Te Kāhui Maungā were the earliest inhabitants in the area, arriving before many other Māori (cf., Waitangi Tribunal, 2013). They were also known as the descendants of Paerangi-i-te-Moungaroa, also known as Paerangi-i-te-Whare-Toka. Paerangi is an ancestor of Ngāti Rangi, a chief who is described in the narratives as one of the first inhabitants of New Zealand (i.e., the “original people of the land”). The names of his daughters have specific meanings, Rangituhia meaning “written in the heavens”, Rangiteauria meaning “the joining of the heavens to the earth”, and Uenuku Manawa Wiri meaning “the rainbow, the anchorage of the pulsating heart”.

European history

From the time of European arrival and settlement of the central North Island during 1800 Māori were recognised as the native inhabitants and custodians of the land. During the mid 1800s, increasing settlement and interest in New Zealand from overseas required land to be secured by the Crown for purchase. During this period, a Native Land Court collected a large amount of information on the connections that iwi (i.e., tribes) and individuals had with the land. Unfortunately, the Courts of the time were focused on ownership rather than tribal identity, history and traditional land tenure systems, resulting in individual cultural identity being overlooked, poorly recorded and not understood.

The events of the formation of the Tongariro National Park (comprising Mt. Ruapehu, Mt. Tongariro and Pihanga volcanoes; Figure 1) with the gifting of a 2 km radius of land around the peak of Mt. Ruapehu by Horonuku Te Heuheu, on behalf to the neighbouring Tūwharetoa tribe, also did not take into account Ngāti Rangi culture and status over their tribal region and ancestral maungā (mountain). Ngāti Rangi and other iwi from the Whanganui district (Figure 1a) strongly protested this action and asked for their areas to be subdivided out of the National Park. This was against the thinking of the current government and the National Park was established (cf., Waitangi Tribunal, 2013).

Ngāti Rangi, like many other maori tribes, has a rich belief system that has developed over the last 1000 years of occupation, with numerous spiritual and ritualistic practises that occur at different times and locations. A large number of these practises have disappeared due to the introduction of European culture and Christianity. However, several historical accounts that form the basis of Ngāti Rangi belief system are now publicly known and treated as stories, myths and legends.

Many of these stories have been over simplified over the years with many different versions being portrayed. Unfortunately, the real meanings behind many of these stories and practices have been lost or altered to be consistent with European beliefs. This has forced Ngāti Rangi to guard the remainder of their history and spiritual connections to their rohe pōtae (i.e. tribal homeland), to ensure that their mana (status) and principles are not disrespected and that they endure.

Te Maungā

Paramount in Ngāti Rangi belief structure and culture are the volcanoes that make up Te Kāhui Maungā, in particular Mt. Ruapehu. The dominant longstanding feature in the landscape (Figures 1 and 2) is central in creation records, chronicles of settlement, and ritualistic practises. The mountain is viewed as touching the heavens and is seen as a place of gods and the resting place of their ancestors (C.Wilson, personal communication 2012).

The connection Ngāti Rangi have with the maungā is highlighted in its name Te Kāhui Maungā ki Tangaroa. The name signifies both their connection to the creation of the land, their place of belonging (and the term used to describe their natural grouping or iwi) and the source of their awa/wai (river system) and mouri (Ngāti Rangi dialect for mauri, meaning Life Principle, Life Force; cf. Best 1982). Ngāti Rangi whakapapa (i.e., genealogy) refers to the people that fished up and created the North Island. Their spiritual beliefs centre on the atua (gods and spiritual guardians): Tangaroa (Guardian of the Ocean), Ranginui (Father Sky), Papatūānuku (Mother Earth), and Ruaumoko (Guardian of Earthquakes and Volcanoes, the youngest son of Rangi and Papa), all of them connected by water and before the island was “fished up” by the Polynesian demi-god Māui. The “fish” would breath through a hole or vent connected to the top of the South Island called ‘Te Ihungangana a Ruapehu i rō wai’; when fished up, the birth of Ruapehu calmed the fish.

Mt. Ruapehu later became known as Matua te Mana (the powerful one) with himself and the Te Wai-ā-moe, which refers to the Crater Lake, as the spring that brought forth life from Papatūānuku (Mother Earth), supplying spiritual and physical sustenance to the land and Ngāti Rangi.

Maori belief structure

The beliefs and values of Māori are based on their relationship with the natural environment and their influence on management. Primary values associated with land include: tikanga (customs) and whakapapa (genealogy), which form the basis of any kaupapa Māori (knowledge, skills, attitudes and values of Māori society) process. Other Māori environmental concepts such as tāonga (treasures), mouri (life force), wairua (spiritual health and wellbeing), kaitiaki (guardians), and ahi kā (unbroken connections) are important concepts used in environmental management to essentially monitor the state of the (cultural/Māori) environment or the interconnectedness. Kaitiakitanga (guardianship) is another more recent concept, which provides the framework to put into practice these concepts and applies them to today’s western management systems and legislation. Kaitiakitanga refers to the sustainable access, use, and conservation of natural resources, developed by a specific community occupying a particular geographical area (cf., Marsden 1992). None of these concepts form or relate to any legislation or policy that guides natural hazard identification or the emergency management process.

Kaupapa Māori research

Kaupapa Maori is the term used for the indigenous, epistemological research system in New Zealand, which includes the initiation, procedures, evaluations, construction and distribution of newly defined indigenous knowledge (cf., Bishop 1999, Moewaka Barnes 2000). Many indigenous cultures have traditionally occupied fertile, active volcanic areas. In New Zealand, Māori have observed and monitored, as well as responded to and recovered from, numerous hazardous (volcanic) events during the last ~800 years (Cashman and Cronin 2008; King et al. 2007, Severne 1995). The knowledge, referred to as mātauranga māori, gained from these experiences is rarely considered when scientifically identifying volcanic hazards, yet it does contain a unique, valid epistemology and data (Roberts 1995, Durie 1996, Durie 1998). By extracting and combining portions of both Māori and western science within an applied spatial context, utilising both scientific and kaupapa Māori frameworks (Smith 1990), we can begin to develop unique solutions to natural hazards and increase resilience to hazard events (cf., Rainforth et al. 2012).

Methods

We suggest that body language in combination with other forms of human expression, such as, fine arts, music and poetry, are highly effective tools to teach geological and volcanological concepts. By reconsidering the concept of “The body as a cultural object”, discussed by authors such as Foucault (1977), Mary Douglas (1973), (Merleau-Ponty 1945, In: Silverman 1976), and Gardner (1993), it is possible to develop different strategies using the body language to experience, adopt, and translate the scientific information. The concept of “body language” refers to the collective expressions, which use the physical body as the main subject of human perception, nonverbal expression, and communication (cf., Merleau-Ponty 1945, In: Silverman, 1976; Fran 1988). Body expression is conceived as an intrinsic human, non-verbal ability articulating personal sensitivity, thoughts, imagination, and creativity, complementing other expressive tools such as, talking, painting, and writing (cf., Stokoe and Schächter 1977). It has been recognized since the 1970s as a powerful pedagogical tool (Stokoe 1978), which encompasses the concepts of (1) free-style dance, as an individual search; (2) dance to move, to communicate, and to create or improvise (Kalmar 2006). In addition, body language is encompassed within the concept of “bodily knowledge”, also known as “somatic knowledge”, which is a wide pedagogical research field comprising the ways humans understand themselves and their environment through the body, and make meaning of the world through their bodily experiences (Green 2002).

For this project, we chose the Ngāti Rangi children as the main representatives of the tribe to work with. The reason for this selection was based on the hypothesis that children are (1) excellent receptors and questioners of knowledge, (2) participative in an innovative classroom, and (3) communicators to older generations by sharing their learning with their families. Also, children’s psychomotor abilities and development are expected to be better than in ordinary adults. We adapted the strategies explained below to the conditions of Ngāti Rangi population, which had one Māori medium primary school at Ohākune Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Ngāti Rangi, which is taught between 80-100% in Te Reo Māori and comprised 20–26 students between 5 and 13 years old in 2012–2013 (grouped within two classrooms). The initial stage of the project consisted in meetings between the volcanologist and the Māori Principal of the primary school. In this phase, the volcanologist could learn about Ngāti Rangi history, the meaning of Mt. Ruapehu for the community, the relationship between the tribe and the volcano, and how Māori explain, understand and relate to the origin of the Universe, Planet Earth, and volcanic activity in general, and to Mt. Ruapehu, in particular. The questions from the Principal to the volcanologist were also raised in this initial phase, together with the main interests of the community around how volcanology could contribute to and straighten their knowledge system and practices. Since Mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) is transmitted across generations through oral tradition (prayers, narratives and songs), the meetings served to clarify the meaning of the narratives, with particular attention to all Māori etymology and toponomy referring to Mt. Ruapehu and related activity.

From the first stage a rich database resulted, which helped to identify the concepts within the mātauranga that could overlap with western scientific (geological-volcanological) theories. From this process, a correlation between the indigenous and geological knowledge systems could be established and the main teaching subjects were selected: (1) The origin of the Universe, Solar System, and Planet Earth; (2) The Structure of the Earth; (3) Earth dynamics (covering tectonics, earthquakes, magma, and volcanic activity).

The third stage consisted in the design of multidisciplinary workshops focused on teaching geosciences by using the body language and knowledge developed in performing arts. The starting motive was always the Māori perception of each concept, followed by the presentation of the corresponding scientific point of view. The entire aim was to evidence the agreement between both systems and to bring about the need for respectful and reciprocal interactions between people, natural processes and resources to prevent disasters.

A series of five workshops were designed, each one consisting of: (1) an introductory session (~1 hour long) using different types of body expression exercises, including Contact-improvisation dance (Smith and Nelson 1997), theatre, and interpretative dance (Root-Bernstein and Root-Bernstein 2003, Servos 1981), improvisational playmaking and game-dynamics (Boal 1979, 2002). The traditional narratives were recreated (i.e., performed) during this sessions, by using them as motives and guides for the improvised body movement/expression. This activity was followed or alternated by a guided-dance part to first experience the physical processes addressed in each subject (e.g., The Origin of the Universe, of the Planet Earth and all forces of nature), in order to have an initial “empirical-somatic” comprehension of the phenomena before receiving the theoretical explanation. Therefore, the methodology is based on experiencing concepts and physical phenomena through the body movement, body expression, and by acquiring body knowledge at first. Contact-improvisation dance, for instance, is based on the improvisation that arises when two bodies establish contact, following the physical laws that govern their motion: gravity, momentum, and inertia. Therefore, it is an extremely useful technique to experience with the body these physical laws. The bodywork was occasionally shortly interrupted to reinforce the oral tradition and to provide the scientific explanation of the same experience.

(2) A session (~1 hour long) of interactive talks followed, to construct the concepts experienced with the body in the first session. The theoretical scientific background was explained in continuous feedback with the Māori view about the same processes. Audio-visual aids, such as images, videos, and power point presentations were used in this session to specify and clarify the concepts by visualizing real natural images or virtual models. This session had to be strongly interactive, allowing streams of questions asked by the children to be discussed and answered. (3) A subsequent practical session varied from observations directly in the field (on Mt. Ruapehu) to laboratory or hands-on exercises (e.g., construction of volcano models; Diet-Coke© and Mentos© experiment following Coffey 2008). (4) Collaborators (teachers and artists) conducted a further session, which varied according to the workshop. Learned key concepts were synthetized and posed as motives to produce other art forms, such as poetry, pictures, paintings, and songs. This activity (1 hour to several days) allowed further assimilation of the learned concepts. During all stages, a collection of existing and absent terms in Te reo Māori language was recorded, in order to build up a glossary of geological terms in the native tongue.

Finally, the documented process and artistic products were later used to (5) produce a teaching tool in video and power point presentation formats. This tool was left as a permanent resource to the school for continuing work with future generations. It was also given to other teachers, other members of Ngati Rangi community, and researchers conducting investigation on Māori culture, mātauranga, and risk mitigation strategies, to be used as an interactive tool in order to extend the process to the elder generations.

Results

Mātauranga Māori (the Māori Knowledge System)

The meetings (hui) and conversations (kōrero) between volcanologists and the Princiapal focused on the Māori perception and their explanation about the Origin of the Universe, the Planet Earth, Earth dynamics, Mt. Ruapehu and the relationship between the tribe and the volcano. The discussions emphasized the concept of Kaitiakitanga (guardianship), which encompasses the philosophical and practical components that establish the local indigenous environmental ethics. By protecting and managing the land that Māori have been occupying over generations, where the community exercises authority for decisions made regarding the land (mana whenua) and manages natural resources, the guardianship enhances the health of valued species (mouri o ngā tāonga) and the local ecosystem (cf., Forster 2011). Therefore, Māori environmental theories and practices derive from long (hundreds of years) cultural and ecological relationships with their ancestral land.

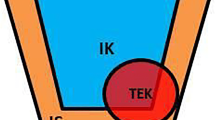

To understand the meaning of the Māori territory, it is crucial to clarify their explanation about the origin of the world known by humans. In the Māori tradition, the Universe is a dynamic process, a continuous transformation allowing the “unfolding of consciousness and thought”. Its roots comprised (1) Te Korekore, meaning the original void and the potential being (Figure 3); (2) Te Pō, meaning the original darkness and the world of becoming; and (3) Te Ao Mārama, meaning the world of light, the world of being. Māori genealogy starts from here, from the beginning of the universe, developing into the establishment of time-space, night and day, and the formation of the male and female principles: Ranginui (Father Sky) and Papatūānuku (Mother Earth). From their union all the spiritual powers were born and became the guardians of their various domains, including the ocean, the wind, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, forests and birds, the cultivated food, uncultivated crops, human beings, and war. Within Māori cosmogony, humans were born in the latest time of this genealogy (cf., Kowhai Consulting Ltd. 2004).

The Tino Rangatiratanga Flag, which became officially the Māori flag of Aotearoa (New Zealand) in 1990. Designed by Hiraina Marsden, Jan Dobson and Linda Munn. Text by Walter Erstich (cf., Paora et al., 2011).

Along with the unfolding universe, the ability of cosmic processes to give, but also, to destroy has been widely recognized by Māori. There, the concept of Tapu arises. It refers to the sacred and also to the forbidden places, activities, and things, and it is therefore used as a protective measure that establishes ethical and practical norms, also imposing a social control. Tapu is the Māori system to cultivate appreciation and respect for another human being, another form of life, and any life force (cf., Kowhai Consulting Ltd. 2004). Volcanic craters, crater lakes, geothermal springs, water springs, and other specific landscapes are tapu. For example, Ngāti Rangi refers to the Crater Lake on Ruapehu as Te Wai a Moe, the Sleeping Water, which is a place of Tapu. This is not trivial, since the most recently frequent eruptions of Ruapehu regard unpredictable phreatic events that may not significantly impact a large area, but certainly is a threat for visitors on the volcano slopes and crater rim. Likewise, a story about the origin of the Mangawhero River from a tear escaped from Ranginui as he got separated from his lover Papatūānuku could be used as a starting point to explain the different lahar triggering mechanisms. Similarly, the Rangipōs desert (Figure 1b) is also referred as Tapu, corresponding, from the volcanological perspective, to the proximal and medial locations of pyroclastic deposition during past, sustained Plinian and subplinian eruption columns. Tapu can be therefore considered as a native hazard mitigation strategy (cf., Tapuke et al. 2006, King et al., 2007, Grattan and Torrence 2010), which identifies a place as sacred and forbidden because it is known to be dangerous, ultimately discouraging people to approach (e.g., it regulates exposure to volcanic hazards).

A recurrent story within the Māori narratives regards the “Three baskets of knowledge”. In the story, the supreme creator Io gave these baskets to Tane, the god and guardian (kaitiaki) of the forests and direct ancestor of the human kind. The three baskets correspond to: (1) the knowledge beyond space and time, the ultimate, and unknown to us, reality; (2) the “womb of the universe”, the initial knowledge from which the universe originated; (3) “that before us”, corresponding to the knowledge that we acquire through the senses allowing the current understanding about the natural world around us. Within this context, the Māori education system develops, providing the first principles or ground rules, and the customs from which “one would guide oneself” (cf., Kowhai Consulting Ltd. 2004). This “living and behaviour guide” is transmitted throughout generations through the karakia (prayers), waiata (songs), kōrero (oral stories), and other forms of performing arts collectively named Kapa-Haka.

Ngāti Rangi’s starting point when approaching any discussion about Mt. Ruapehu was their karakia (prayer) to the volcano, titled “He Ruruku: Mai ara ra!” (Appendix 1). The prayer recalls the tribe’s genealogical link to Mt. Ruapehu, which is not simply described as a geomorphological accident consisting of Rua (two) Pehu (craters), but is mainly referred as: (1) Koro (Grandfather), (2) Matua te Mana (The powerful progenitor), and (3) Te Whare Toka o Paerangi (The house of stone of Paerangi, their ancestor).

The karakia mentions the “Mountain Clan”, which refers to Mt. Ruapehu (Matua te Mana-Absolute Wisdom), Mt. Tongariro (Matua te Toa - Absolute Warrior), Ngāuruhoe (Matua te Pononga-Absolute Negotiator), Pihanga (Matua te Hine-Absolute Feminine), and Mt. Taranaki (Matua te Tapu-Absolute Sacredness) (Figure 1b). The Māori story explains the actual distribution of the volcanoes, with Mt. Taranaki location offset to the west coast and detached from the N-S volcanic trend within the Central Volcanic Pleateau. These volcanoes conformed the ancestral mountain clan and originally lived together in the central North Island. Pihanga represents the only female character and was engaged with Tongariro. However, a love affair with Taranaki provoked conflict, from which Tongariro got furious and finally “blew his top”. Within the Ngāti Rangi version of this story, Ruapehu, Koro (the grandfather), watched the scene with worry and decided to send Mt. Taranaki (who was responsible for the sacred kōrero of the clan) to the west, with the responsibility to “be the guardian of the setting sun”. From there, he cries whenever he reminds Pihanga and sends his caresses from the West in the form of clouds. The story clearly places Ruapehu as the wise elder, Matua te Mana, who protects Ngāti Rangi from the force of Tongariro. Although we could not completely confirm the entire story with geological evidence, Mt. Ruapehu Plinian eruptions (>27-11 ka cal. BP) are older than Tongariro largest explosive events (>10-7 ka cal BP). Also, the shape of Mt. Tongariro has progressively changed with time as violent eruptions and sector collapses have occurred (cf., Donoghue et al., 1995; Cronin and Neall, 1997; Narin et al. 1998; Moebis et al., 2011).

Ruapehu also plays a central role in Ngāti Rangi songs and other stories, where it is referred as the shining scale of the Great Fish caught by Māui (Polynesian demigod), which subsequently became the North Island of New Zealand (Te Ika o Māui; cf., Te Ahukaramū Charles Royal 2012). From the conversations, it was clearly understood that from the Māori perspective, the land and the volcano clearly preceded human occupation in the cosmogony.

Mt. Ruapehu is therefore considered one of the ancestors who provides benefits to the tribe and regulates the balance of their territory. “If he needs to do his mahi (job) then we need to let him. He needs to do what he needs to do”. Ngāti Rangi permanently emphasized this perception about the volcano, constantly repeating that the tribe does not consider Ruapehu as a hazard; indeed, Ngāti Rangi asked volcanologists to avoid this term from the beginning of this project. During the meetings there was a recurrent message reinforcing the tribe’s lack of fear in front of volcanic activity of Ruapehu, and the strong acknowledgement for all the benefits provided by the volcano, which included: (1) Their water resources, embracing rivers, water springs, the Crater Lake, and the Rotokura lake (located on the SE ring-plain of Ruapehu and considered to hold water with healing properties). (2) The ski field, which is the main source of economical and recreational activities during winter. (3) The productive volcanic soils, and (4) protection from the eruptions of Tongariro (last erupted in 2012; Jolly and Cronin 2014).

Bridging Māori and western-gescience systems

By integrating Māori and scientific perceptions, a conceptual map was proposed (Figure 4; Table 1) in which for each Māori concept there corresponds an analogue scientific one. The resulting lines and arrows connecting concepts and processes attempt to correlate the two.

For example, the genealogy from creation to mankind detailed by Mātauranga Māori, starting from the root-cause, the original void, and developing into the expansion energy, primordial memory, sub-conscious wisdom, and the seed-word breath of life, can have an equivalent in science, starting from the Big Bang, and developing into the formation, replication, transcription, and translation of DNA. Similarly, the Māori notion about the unfolding of life is comparable to the scientific theory of evolution and the typical spiral representation of the geological time.

In the resulting integrative map (Figure 4), the lessons from the past experiences and from the observation of the present moment play a role in the mental projection of the future. From the mythological point of view, past experiences are lessons for present generations; from the scientific, geological point of view, the observations of current processes are the key to reconstruct the past events (Principle of Uniformitarianism). Both systems look forward to study trends and envisage the future (events/generations), which is a key procedure to design strategies for risk mitigation and emergency planning.

Workshops for Māori children

Through the development of the conceptual map (Figure 4; Table 1), the idea of humans as part of the environment, rather than separated from natural processes was reinforced, and a sense of responsible participation could be shown and shared with children. The co-validation of Mātauranga Māori and western Geosciences aimed to reach an agreement between both perceptions, which helped to design four, one-day long workshops (one per school-term), where geology could be taught without interfering but nurturing and being nurtured by the traditional Māori understanding.

At the end of the first workshop (Te whakapapa o Papatūānuku), the concepts of Time-Space, Matter and Energy, the Laws of Thermodynamics, the Sates of Matter, The four Fundamental Forces, the Origin of the Universe, Solar System, Planets, Earth structure, and the importance of soils and water conservation were effectively shared (Table 2a and 2b).

At the end of the second workshop (Ruaumoko shakes), the concepts of Tectonic Plates, stress-and-strain, earthquakes, seismic waves, Earth crustal response to stress (i.e., fragile, ductile, plastic, and elastic behaviour of matter), orogenesis, and the general theories of Earth’s dynamics were integrated with the stories of Ruaumoko, the god of earthquakes and volcanoes (Table 3).

The third workshop (Te Whare Toka ō Paerangi) reviewed the structure of the Earth and focused on the Tectonic Rock Cycle. This was successfully integrated to the Ruapehu narratives as being the “House of stone” of Paerangi, the Ngāti Rangi ancestor (Table 4).

The fourth workshop that could be developed within the time of this project (Matua te Mana and Crystals) focused on the generation of magma, magma crystallization, degassing, and the origin of volcanoes (Table 5). The last workshop (Te Mahi o Ruapehu) focused on volcanic eruptions, volcanic products, and their benefits to humans and, in particular, to the Ngāti Rangi people (Table 6).

As described above, all workshops included an initial session of bodywork by integrating Contact-Improvisation dance, partner-yoga, and somatic-dance exercises, which provided a guided, free-style movement with scientific and traditional native contents (here called Earth-Contact Dance). The images, movements, and questions driven by the instructor pulled out the attention towards observation of the own body and construction of empirical knowledge. After the physical sensations were explored through the body language the children had time to narrate their perceptions. From here, the physical-laws and geological concepts were constructed together with the teachers, making always the paragon with Māori knowledge. The process resulted in a continuous creative education practice during which the teacher was constantly inducing research by the students. Rather than limiting the lessons to a unidirectional talk by the teacher, the permanent thinking-induction through questions to the children allowed the construction of concepts by themselves. The emotion triggered through this process allowed the assimilation of the learned concepts and the motivation to share their new findings with their families, promoting communication to elder generations.

Because of the conditions of this project, the guided movement and scientific explanations were given first in English, followed by the translation in Te reo Māori to assure comprehension.

The results were surprisingly positive because of the highly active participation and creativity of Ngāti Rangi students. Throughout frequent questions along the entire project we could confirm the appropriation of geological and traditional knowledge without conflict.

Resulting tangible products include a collection of poems, paintings, crafts, pictures, and a song. These products were integrated within a video and a power-point presentation formats, as a teaching tool for children and adults (being adaptable to all levels), for future generations.

Discussion

Expectations from the teaching tool

The didactic video/.ppt resource prepared for Ngāti Rangi Iwi is a continuous process, a compilation of visual and auditory material to provide insight into knowledge platforms uniting Ngāti Rangi historical and intellectual tenets, code of conservation beliefs and practices, and Geosciences. It emphasizes the interconnectedness of Ngāti Rangi knowledge, history, and contemporary teaching sources (poems and songs) in a learning atmosphere that engaged the children at primary school.

The following points below highlight some discussion points, which can be used for the development, integrated learning to produce a Ngāti Rangi geoscience resource. It provides a starting point to develop an entire glossary of geological terms in the native language, providing an instrument to support native language revitalisation, reclamation, and regeneration. It could be also used as a tool to inspire new songs, poems, dances, and theatre plays within the local art style, nurturing the tradition and knowledge for future generations. It ultimately brings an opportunity for Ngāti Rangi to lead in worldwide efforts to reinforce the capabilities of indigenous communities to manage volcanic risk reduction.

The message from Ngāti Rangi to the scientific community

Forced evacuation and displacements of native people away from their ancestral land impact their entire social, cultural, economical, and ecological network, which may increase their vulnerability in future events. Rather than imposing the results of western science and governmental decisions on indigenous communities exposed to volcanic activity, the participation of the community and the recognition of their own, empirical knowledge developed throughout generations of land occupation may be a better way to decrease social vulnerability. Empowering native and scientific community awareness and cooperative prevention strategies during volcanic repose periods, may enhance concerted participation in emergency planning and response.

This project showed how traditional knowledge and western, modern sciences are not necessarily exclusive or in conflict. Their integration can in fact be a powerful education tool to empower native communities to actively contribute to volcanic risk mitigation strategies, and take their insights abroad to other indigenous and non-indigenous groups and institutions leading to disasters prevention. Specifically, the Ngāti Rangi objection to referring to volcanic activity of Mt. Ruapehu as a “hazard” (with a potential negative outcome) is an invitation to the scientific and governmental communities to include traditional knowledge within emergency planning strategies. The tribe emphasized a perception about the volcanic activity, which has been more likely to produce benefits than disasters over generations. Within this point of view, the Māori community asks scientists and government to guide human kind behavior, politics, and decisions by considering that it is not about controlling the Earth and natural processes, but about living in harmony with volcanism. In a sense, this is an invitation to use science in a way that supports the traditional conservation practices and that proposes mitigation strategies worked within consensus with the local native communities. The ultimate aim is to reduce vulnerability and optimize social response during volcanic crises.

Conclusions

By using the “body” as the mirror of our own point of view about the world rather than being an object in the world (Merleau-Ponty 1945), it is possible to understand scientific ideas by experiencing and feeling them first, and then by adding words to the given information to construct concepts. We showed how physical processes and concepts, such as the principles of thermodynamics, the origin of the Solar System and formation of Planet Earth, as well as how earthquakes and volcanoes work can be recreated and experienced through basic exercises of Contact-Improvisation dance, somatic dance, games, and other ludic activities based on body language and bodily knowledge. We showed how the resulting Earth-Contact Dance could bridge languages that could be misinterpreted as contradictory, such as native traditional belief systems and western earth sciences, to create a new way of looking at volcanic activity and hazard.

Blending traditional indigenous and scientific knowledge systems reduces social vulnerability by: (1) increasing awareness of volcanic phenomena by the local indigenous communities, (2) increasing awareness of scientists and government about the cultural and vital relationship between the communities and volcanoes, and (3) providing a better environment for active community participation and potential positive response during emergency management. The integrative approach can contribute to living safely with active volcanoes and reducing risk, during eruptive and non-eruptive periods.

References

Alexander DE (1993) Natural Disasters. University College London Press, Kluwer, Dordrecht/London, p 632

Anderson EN (1996) Ecologies of the heart: emotion, belief and the environment. Oxford University Press, New York, p 272

Berkers F, Kislalioglu M, Folke C, Gadgil M (1998) Exploring the Basic Ecological Unit: Ecosystem-like Concepts in Traditional Societies. Ecosystems 1:409–415

Best E (1982) Maori religion and mythology being an account of the cosmogony, anthropogeny, religion beliefs and rites, magic, and folk lore of the maori folk of new Zealand. Part 2. New Zealand Electronic Text Collection Te Puhikotuhi o Aotearoa. PD Hasselberg, Government Printer, Wellington, New Zealand, p 682

Bishop R (1999) Kaupapa Maori Research: An indigenous approach to creating knowledge. In: Robertson N (ed) Maori and psychology: research and practice - The proceedings of a symposium sponsered by the Maori and Psychology Research Unit. Maori & Psychology Research Unit, Hamilton, pp 1–6

Boal A (1979) Theatre of the Oppressed. Pluto Press Limited, Australia, 184

Boal A (2002) Games for actors and non-actors. Roudlesge, London, p 301

Cashman KV, Cronin SJ (2008) Welcoming a monster to the world: Myths, oral tradition, and modern societal response to volcanic disasters. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 176:407–418

Coffey TS (2008) Diet Coke and Mentos: What is really behind this physical reaction? Am H Phys 76(6):551–557

Christenson BW, Wood CP (1993) Evolution of a vent-hosted hydro- thermal system beneath Ruapehu Crater Lake, New Zealand. Bull Volcanol 55:547–565

Cronin SJ, Neall VE, Palmer AS (1996) Geological history of the northeastern ring plain of Ruapehu volcano, New Zealand. Quat Int 34(36):21–28

Cronin SJ, Neall VE (1997) A late Quaternary stratigraphic framework for the northeastern Ruapehu and eastern Tongariro ring plains, New Zealand. N Z J Geol Geophys 40:179–191

Cronin SJ, Hodgson KA, Neall VE, Palmer AS, Lecointre JA (1997) 1995 Ruapehu lahars in relation to the late Holocene lahars of Whangaehu River, New Zealand. N Z J Geol Geophys 40:507–520

Cronin SJ, Cashman KV (2008) Volcanic oral traditions in hazard assessment and mitigation. In: Gratton J, Torrence R (eds) Living under the shadow: Cultural impacst of volcanic eruptions. Left Coast Press, CA, pp 165–176

Donoghue SL, Neall VE, Palmer AS (1995) Stratigraphy and chronology of late Quaternary andesitic tephra deposits, Tongariro Volcanic Centre, New Zealand. R Soc N Z 25(2):112–206

Douglas M (1973) Natural Symbols, Exploration in Cosmology. Routledge, New York, p 177

Durie MH (1996) Mātauranga Māori: Iwi and the Crown: A Discussion Paper. Paper prepared for mātauranga Māori hui. James Henare Māori Research Centre, University of Auckland, pp 1–4, 26 September

Durie MH (1998) Mana, Te Kawanatanga: The Politics of Māori Self-determination. Oxford University Press, Auckland

Feiring B (2013) Indigenous peoples’ rights to lands, territories and resources. International Land Coalition, Rome, p 94

Forster M (2011) Kaitiakitanga: A Māori Environmental Ethic. In: Tomlins-Jahnke H, Mulholland M (eds) Mana Tangata, Politics of Empowerment. Huia Publishers, New Zealand, pp 221–241

Foucault M (1977) Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan, vol 1975. Allen Lane, Penguin. First published in French as Surveiller et punir, Gallimard, Paris London, p 333

Fran JL (1988) Dance/Movement Theraphy. A healing art. National Dance Association and American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance., p 354, ISBN-0-88314-380-1

Gardner SB (1993) “Still iving flesh”: Beckett, Merleau-Ponty, and the Phenomenological Body. Theatr J 45:443–460

Grattan J, Torrence R (2010) Volcanic Oral Traditions in Hazard Assessment and Mitigation. In: Living under the shadow: cultural impacts of volcanic eruptions. Left Coast Press., pp 172–202

Green J (2002) Somatic knowledge: The body as content and methodology in dance education. J Dance Educ 2(4):114–118

Gunderson LH, Holling CS, Light SS (1995) Barriers and bridges to the renewal of ecosystems and institutions. Columbia University Press -Nature, New York, p 593

Hackett WR, Houghton BF (1989) A facies model for a Quaternary andesitic composite volcano, Ruapehu, New Zealand. Bull Volcanol 51:51–68

Jolly AD, Cronin SJ (2014) From eruption to end-user; bridging the science-managment interface during the 2012 Te Maari eruption, Tongariro Volcano, New Zealand. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 286:183

Kalmar D (2006) Que es la expression corporal: a partir de la corriente de trabajo creada por Patricia Stokoe. Lumen Humanitas Ed, Buenos Aires, Argenitina, 176

Kilgour G, Manville V, Della Pasqua F, Graettinger A, Hodgson KA, Jolly GE (2010) The 25 September 2007 eruption of Mount Ruapehu, New Zealand: directed ballistics, surtseyan jets, and ice-slurry lahars. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 191:1–14

King DNT, Goff J, Skipper A (2007) Māori Environmental Knowledge and natural hazards in Aotearoa-New Zealand. J R Soc N Z 37(2):59–73

King DNT, Skipper A, Tawhai WBM (2008) Māori Environmental Knowledge of local weather and climate change in Aotearoa-New Zealand. Climate Change 90:385–409

Kowhai Consulting Ltd (2004) Certificate in Iwi Environmental Management and Trusteeship: Kaitiakitanga. Te Wānanga o Aotearoa., p 57

Lowe DJ, Newnham RM, McCraw JD (2002) Volcanism and early Māori society in New Zealand. In: Torrence R, Grattan J (eds) Natural disasters and cultural change. Routledge, London, England, pp 126–161

Lube G, Cronin SJ, Procter J (2009) Explaining the extreme mobility of volcanic ice-slurry flows, Ruapehu volcano. New Zealand Geol 37(1):15–18

Ludwig D, Hilborn R, Walters C (1993) Uncertainty, resource exploitation and conservation: lessons from history. Science (Washington) 260:17–36

Marsden M (1988) The Natural World and Natural Resources: Māori Value Systems and Perspective Māori. Resource Management Law Reform Working paper no. 29, Part A. Ministry for the Environment, Wellington

Marsden M (1992) Kaitiakitanga: a definitive introduction to the holistic worldview of the Māori. In: Royal TAC (ed) The Woven Universe: Selected writings of Rev. Māori Marsden. Te Wānanga-o-Rawkawa, Ōtaki

McClelland E, Erwin PS (2003) Was a dacite dome implicated in the 9,500 B.P. Collapse of Mt Ruapehu? A palaeomagnetic investiga- tion. Bull Volcanol 65:294–305

Merleau-Ponty M (1945) Phenomenology of Perception, Gallimard (ed). Translated by Colin Smith, New York: Humanities Press, 1962; London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1962; translation revised by Forrest Williams (1981), 469p.

Moebis A, Cronin SJ, Neall VE, Smith IE (2011) Unravelling a complex volcanic history from fine-grained, intricate Holocene ash sequences at the Tongariro Volcanic Centre, New Zealand. Quatern Int 246:352–363

Moewaka Barnes H (2000) Kaupapa maori: explaining the ordinary. Whariki Research Group, University of Auckland. Pacific Health Dialog 7:13–16

Narin IA, Kobayashi T, Nakagawa M (1998) The ~10ka multiple vent pyroclastic eruption sequence at Tongariro Volcanic Centre, Taupo Volcanic Zone, New Zealand: Part 1. Eruptive processes during regional extension. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 86:19–44

Neall VE, Cronin SJ, Donoghue SL, Hodgson KA, Lecointre JA, Palmer AS, Purves AM, Stewart RB (2001) Lahar hazards map for Ruapehu volcano. Institute of Natural Resources–Massey University, Soil and Earth Sciences Occasional Publication No. 1

Palmer BA, Neall VE (1989) The Murimotu Formation, 9500 years old deposits of a debris avalanche and associated lahars, Mount Ruapehu, New Zealand. NZ J Geol Geophys 32:477–486

Pardo N, Cronin SJ, Palmer A, Németh K (2012) Reconstructing the largest explosive eruptions of Mt. Ruapehu, New Zealand: lithos- tratigraphic tools to understand subplinian-Plinian eruptions at andesitic volcanoes. Bull Volcanol 74:617–640

Paton D, Millar M, Johnston D (2001) Community Resilience to Volcanic Hazard Consequences. Nat Hazards 24:157–169

Paton D, Smith L, Daly M, Johnston D (2008) Risk perception and volcanic hazard mitigation Individual and social perspectives. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 172:179–188

Procter JN, Cronin SJ, Zernack AV (2010) Landscape and sedimentary response to catastrophic debris avalanches, Western Taranaki, New Zealand. Sediment Geol 38(1):67–70

Rainforth H, Procter J, Black T, Harmsworth G, Pardo N (2012) Exploring indigenous knowledge for assessing volcanic hazards and improving monitoring approaches. Abstracts Cities on Volcanoes 7, Colima, México.

Roberts M (1997) Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Resource Management Systems: Past, Present and Future Perspectives, draft paper. In: Williams D (ed) Mātauranga Māori and Tāonga: The nature and extent of Treaty rights held by iwi and hapū (I Indigenous flora and fauna; II Cultural heritage objects; III Values and traditional knowledge). Auckland University, New Zealand, Waitangi Tribunal report for the Wai 262 claim

Root-Bernstein M, Root-Bernstein R (2003) Martha Graham, Dance, and the Polymathic Imagination. A Case for Multiple Intelligences or Universal Thinking Tools? J Dance Educ 3(1):16–27

Paora R, Tuiono T, Flavell TU, Hawksley C, Howson R (2011) Tino Rangatiratanga and Mana Motuhake. Alter Native 7(3):246–257

Servos N (1981) The Emancipation of Dance: Pina Bausch and the Wuppertal Dance Theatre. Modern Drama 23(4):435–447

Severne CM (1995) Traditional use of geothermal resources by New Zealand Māori. Proceedings of World Geothermal Congress, Florence, Italy, pp 401–404

Silverman (1976) Re-Reading Merleau-Ponty”. Telos 29:106–129

Smith GH (1990) Research Issues Related to Māori Education, paper presented to NZARE Special Interest Conference, Massey University, reprinted in 1992, The Issue of Research and Māori, Research Unit for Māori Education. The University of Auckland, New Zealand

Smith NS, Nelson L (1997) Contact Improvisation 25th Anniversary Sourcebook. Collected writings and graphics from Contact Quarterly dance journal 1975–1992. Contact Editions. ISBN 0-937645-04-4, 260 p.

Stevenson MG (1996) Indigenous knowledge in environmental assessment. Arctic 49:278–291

Stokoe P, Schächter A (1977) La Expresión Corporal, Paidósth edn. Barcelona, Spain, p 111

Stokoe P (1978) El movimiento como liberador de potencialidades. In: Gainza V, Hebrón A, Fessler O, Stokoe P. Educación y Expresión Estética, Plus Ultra Edition, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 153p.

Swanson DA (2008) Hawaiian oral tradition describes 400 years of volcanic activity at Kīlauea. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 176:427–431

Tapuke S, Procter JN, Cronin SJ, Roskruge N (2006) Working effectively with tangata whenua in volcanic risk management in Aotearoa-New Zealand. In: Volume A, Conference F (eds) Abstracts Volume, Fourth Conference, Cities on Volcanoes IAVCEI. Instituto Geofisico de la Escuela Politecnica Nacional, Quito, Ecuador, pp 176–177

Te Ahukaramū Charles Royal (2012) Whenua-how the land was shaped-The North and South islands. Te Ara, the Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. URL: http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/whenua-how-the-land-was-shaped/page-2

Tost M, Cronin SJ, Procter JN, Smith IEM, Neall VE, Price RC (2014) Impacts of catastrophic volcanic collapse on the erosion and morphology of a distal fluvial landscape: Hautapu River, Mount Ruapehu, New Zealand. Geol Soc Am Bull B31010:1

Vervaeck A (2012) The impact of cultural and religious influences during natural disasters (volcano eruptions). Earthquake-Reprot.com. http://earthquake-report.com/2012/09/27/the-impact-of-cultural-and-religious-influences-during-natural-disasters-volcano-eruptions/

Waitangi Tribunal, 2013. Nga Iwi o te Kahui Maunga. In: Wai 1130 Te Kāhui Maunga: The National Park District Inquiry Report. Chapter 2: http://www.justice.govt.nz/tribunals/waitangi-tribunal/reports_old/wai-1130-te-kahui-maunga-the-national-park-district-inquiry-report/chapter-2-nga-iwi-o-te-kahui-maunga

Te Huki M (2013) Ko Matua Te Mana (the song dedicated to Mt. Ruapehu, written with the teachers and children of Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Ngāti Rangi at Ohākune) http://www.reverbnation.com/matiuthehooktehuki/songs

Acknowledgements

This project would not have been possible without the active participation and collaboration of all the students at Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Ngāti Rangi (Ngāti Rangi Primary school at Ohākune, New Zealand) between 2012 and 2013. Similarly, we acknowledge Che Wilson (Ngāti Rangi Trust), Kate Arentsen (Massey University), and all the staff of Te Kaupapa o Ngāti Rangi. Special gratitude to all the artists and external pedagogical collaborators who nurtured the workshops with great creativity and support: Matiu Te Huki, Jen Hyde, and Ana GM Sarabia. We gratefully thank Professor John Ham (Hīrangi School, Tūrangi, New Zealand) for requiring, facilitating, and nurturing the development of similar, short workshops at Te Kura o Hīrangi in 2013 (after Mt. Tongariro eruption 2012). He also enriched the discussions about the method. Hanna Rainforth (Ngāti Rangi Trust), Garth Harmsworth (New Zealand Landcare Research), Javier Agustín-Flores, and Professor Shane Cronin (Massey University), are also thanked for their valuable comments, suggestions, and support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

This project was supported by the project “Mātauranga Māori and Volcanic Hazards”, funded by the Natural Hazards Research Platform (grant number 2012-MAU-01-NHRP) of New Zealand. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

NP conceived the study, carried out the meetings with the indigenous communities by representing the volcanology expertise integrated the indigenous and western geoscience systems, designed and leaded the workshops, and drafted the manuscript. HW was the Principal of the māori school at Ohakune, being the main representative and communicator regarding mātauranga māori, mātauranga a Ngāti Rangi. She provided all the resources regarding indigenous knowledge, facilitated the logistics at the school, and translated the instructions from English to Te Reo Maori during the workshops. H. Wilson was the main collaborator during the workshops and participated in the edition of the manuscript. JP, as leader of the main sponsoring project “Mātauranga Māori and Volcanic Hazards”, funded by the Natural Hazards Research Platform (grant number 2012-MAU-01-NHRP), facilitated the logistics at Massey University, the official meetings between the University and Ngāti Rangi, drafted the background of manuscript, and edited the final text. EL contributed to workshops 1 and 4th design and development, provided all the techniques to include responsible use of soils, and guided some of the creative stages of the workshops. TB participated in clarifying the lines of expected results during the process, edited and enhanced the teaching tools, and drafted part of the discussion section of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

NP carried out this project during the last year of her PhD at Massey University (Palmerston North, New Zealand) and during her postdoctoral fellowship at Volcanic Risk Solutions research team of the same university. Her present affiliations are the Colombian Geological Survey (SGC) and Universidad Nacional de Colombia at Bogotá D.C.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Māori prayer (Karakia) to Mt. Ruapehu titled He Ruruku: Mai Ara Ra!

Mai ara rā! Mai ara rā!

Mai ara rā te Tupua!

Mai ara rā te Tawhito!

Tēnei au

Tēnei au te rangahau ana, ki te ao, ki te pō

Kia Ranginui e tū iho nei,

Kia Papatūānuku e takoto ake nei.

Mai ara rā, mai whea ra tōku ahunga mai?

Tāhuri whakataumaha, huri whakamāmā

E te Kāhui Maungā ko wai ra koe?

Inā, Matua Te Mana te aunahi pīataata mātahi

Pikimai Rawea te kai-kukume ake matua whenua rō wai

Te rongo nei ia hīhī,

Te rongo nei ia hāhā me huka tātairango.

Tina, tina toko te manawa ora, he manawa ora!

Ko te Roi-a-Rangi mo Rua-te-Tipua

Ko te Roi-a-Rangi nō Nukuhau e

Te pātukituki ka tū whakahirahira Kāhui Maungā mā.

Ko toka pokohiwi ka hora maru tapu, e Ngā Turi-o-Murimotu

Te ahi kā o Paerangi i te Whare Toka

Te puta mai te Kāhui-o-Rangi, te Kāhui-a-Rua

Tōna hekenga mai i Te Wai-ā-Moe ki Paretetaitonga

Ko te ara hekenga, ko te ara hokinga mo ngā uri kōtuku

Ka tuku, ka tuku atu i ngā hau kaha ia Parakakariki, ia Mouwhakaarahia

Hei tohu, hei whakaatu ki te ao!

Whiti, whano, hara mai te toki!

Haumia! Hui e!

Taiki e!

He Ruruku: Mai Ara Ra! (English translation by Che Wilson, Ngāti Rangi Iwi, 2012)

Let us return to our origins!

Returning to the time prior to common knowledge

Returning to the time of the ancient knowledge

Searching

Understanding the evolution of life

Absorbing the force of Father Universe

Absorbing the energy of Mother Earth

To truly understand who I am

Internalising this learning…

I now know who I am.

I am the first shiny scale of the Great Fish

I am the energy that turned the Fish to Land

Warmth embraced

Cold embraced, I am the blanket of snow

I am the pulse of the Great Fish

I am the tears of the heavens for Rua-te-Tipua

I am the tears of the heavens from Nukuhau

Divine connection, I embody the Mountain Clan

Anointed as custodian of life, as window to the spirit world

I am Ngā Turi o Murimotu.

The fire from the House of Stone of Paerangi, I am

The genesis of the Sky Clan, I am

The genesis of the River Clan, I am

Emanating from out of Te Wai-ā-Moe

The alpha, I am. The omega, I am

The upper winds, I am

The lower winds, I am

This is my declaration!

A declaration sanctified by stone

Let us unite as one

Unite in conscious thought!

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Pardo, N., Wilson, H., Procter, J.N. et al. Bridging Māori indigenous knowledge and western geosciences to reduce social vulnerability in active volcanic regions. J Appl. Volcanol. 4, 5 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13617-014-0019-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13617-014-0019-1