Abstract

Background

In a warmer and more globally connected Arctic, vector-borne pathogens of zoonotic importance may be increasing in prevalence in native wildlife. Recently, Bartonella henselae, the causative agent of cat scratch fever, was detected in blood collected from arctic foxes (Vulpes lagopus) that were captured and released in the large goose colony at Karrak Lake, Nunavut, Canada. This bacterium is generally associated with cats and cat fleas, which are absent from Arctic ecosystems. Arctic foxes in this region feed extensively on migratory geese, their eggs, and their goslings. Thus, we hypothesized that a nest flea, Ceratophyllus vagabundus vagabundus (Boheman, 1865), may serve as a vector for transmission of Bartonella spp.

Methods

We determined the prevalence of Bartonella spp. in (i) nest fleas collected from 5 arctic fox dens and (ii) 37 surrounding goose nests, (iii) fleas collected from 20 geese harvested during arrival at the nesting grounds and (iv) blood clots from 57 adult live-captured arctic foxes. A subsample of fleas were identified morphologically as C. v. vagabundus. Remaining fleas were pooled for each nest, den, or host. DNA was extracted from flea pools and blood clots and analyzed with conventional and real-time polymerase chain reactions targeting the 16S-23S rRNA intergenic transcribed spacer region.

Results

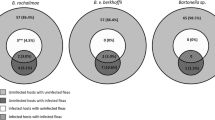

Bartonella henselae was identified in 43% of pooled flea samples from nests and 40% of pooled flea samples from fox dens. Bartonella vinsonii berkhoffii was identified in 30% of pooled flea samples collected from 20 geese. Both B. vinsonii berkhoffii (n = 2) and B. rochalimae (n = 1) were identified in the blood of foxes.

Conclusions

We confirm that B. henselae, B. vinsonii berkhoffii and B. rochalimae circulate in the Karrak Lake ecosystem and that nest fleas contain B. vinsonii and B. henselae DNA, suggesting that this flea may serve as a potential vector for transmission among Arctic wildlife.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Migratory birds play a role in the global movement of pathogens. As the Arctic continues to warm, it is important to understand how movements of millions of migratory birds to Arctic nesting grounds and resulting avian host-parasite relationships may affect the transmission of vector-borne pathogens in Arctic ecosystems. Bartonella spp. are gram-negative fastidious intracellular bacteria that reside within erythrocytes, epithelial cells and macrophages [1,2,3]. Transmission can occur by (i) blood transfusions, (ii) animal scratches, and (iii) through a bite or (iv) the inoculation of feces from blood-feeding arthropods [4, 5]. A wide range of mammalian hosts develop chronic bacteremia, serving as sources of infection for arthropod vectors [6, 7]. The heterogeneity of host species has continued to grow with the discovery of Bartonella DNA in blood from loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta), red-winged blackbirds (Agelaius phoeniceus) and northern mockingbirds (Mimus polyglottos), suggesting that non-mammalian species and their associated ectoparasites may play a role in the maintenance and dissemination of these pathogens [8, 9]. This group of bacteria has been found in numerous hematophagous arthropods, including ticks, sand flies, fleas, and lice [10, 11]. The list of potential vectors could also be larger than anticipated, as Bartonella DNA has recently been detected in avian-associated ectoparasites, including mites (Dermanyssus prognephilus), blow flies (Protocalliphora sialia) and fleas (Ceratophyllus idius) [12].

Previously, Bartonella henselae was isolated from the blood of 3 arctic foxes that were live-captured in the goose colony at Karrak Lake, Nunavut, Canada (67° 14ʹ N, 100° 15ʹ W) [13]. This was the first documentation of B. henselae in arctic foxes and was unexpected as suitable vectors have not been identified in Arctic ecosystems. Transmission cycles generally involve felids and their associated fleas, which are absent in the Arctic [14]. Arctic foxes in this region feed extensively on geese, eggs and goslings [15]. Blood-covered eggs in the colony were first noted in 1991 and were eventually attributed to a host-parasite relationship involving the nest flea, Ceratophyllus vagabundus vagabundus (Boheman, 1865) [16]. Since arctic foxes prey heavily on geese and their eggs, we hypothesized that nest fleas may function as a vector for transmission of Bartonella spp. at Karrak Lake. Therefore, we determined the prevalence of Bartonella spp. in fleas collected from geese, goose nests, and fox dens and blood clots from captured adult foxes. As Bartonella spp. are highly fastidious and difficult to culture, polymerase chain reaction analysis was used to detect DNA in fleas and foxes [17].

Methods

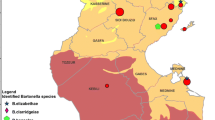

This study was conducted from 2014 to 2018 at the large colony of Rossʼs (Chen rossii) and lesser snow geese (Chen caerulescens caerulescens) near Karrak Lake, Nunavut, Canada (67° 14ʹ N, 100° 15ʹ W). Karrak Lake is in the Queen Maud Gulf Migratory Bird Sanctuary and supports roughly 90% of the world’s population of Ross’s geese and 15% of the population of lesser snow geese during the summer months [18]. Population size of nesting Ross’s and snow geese at Karrak Lake increased from about 400,000 in 1993 to almost 1.2 million birds by 2010, reflecting broader continental population increases by both species of geese [19].

Sample collection

During the summer of 2014, fleas were collected from 5 fox dens located within the Karrak Lake colony by using a 25 × 25 cm square of white flannel placed on a plumber’s snake. This was extended into den entrances for a maximum of three meters and removed after 30 seconds. Similarly, 37 goose nests with evidence of flea infestation (Fig. 1) were sampled using a 25 × 25 cm square of white flannel placed over each incubating nest for one minute as per Harriman et al. [16]. These white flannel squares were placed individually into Ziploc bags and frozen overnight [20]. Fleas from each flannel square were then pooled and placed into a microcentrifuge tube containing 70% ethanol (one tube per den or nest). A total of 827 fleas were collected from goose nests and 86 fleas were collected from den sites.

Forty-eight Ross’s and 54 lesser snow geese were shot (see Ross et al. [21]) as they arrived at the nesting colony in early June 2018, placed into sealed clear plastic bags immediately, and held at ambient temperature overnight. Fleas found in the bag or on the goose were pooled for each host and placed into a microcentrifuge tube containing 70% ethanol. A total of 97 fleas were found on 19% of Ross’s geese (n = 9/48; 95% CI: 10–32%) and 20% of lesser snow geese (n = 11/54; 95% CI: 12–33%).

Fifty-seven adult arctic foxes were live-captured during May 2014–2018 as per Bouchard et al. [22]. Briefly, foxes were caught in box traps and sedated with 0.15–0.20 ml of Telazol® administered intramuscularly [23]. Ear tags were placed in both ears for future identification and blood was collected from the cephalic vein. Samples were then centrifuged, and sera and blood clots were stored separately in freezers until tested. Nest fleas are not active in May and have not been detected on adult foxes.

Flea identification

As the process of mounting fleas on slides for species identification renders them unusable for molecular work, a subsample of roughly 25% (230 fleas from nests and 21 fleas from dens) were identified as C. v. vagabundus using morphological features as per Holland [24] and Lewis & Galloway [25]. All fleas collected from geese were morphologically identified to genus on gross inspection (n = 97), and one was mounted on a slide to verify that it was C. v. vagabundus. Given that there is no DNA sequence data available for this flea species in GenBank, DNA sequences were determined for part of the nuclear 28S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene and the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 2 gene (cox2) for 2–3 representative specimens from dens and nests. Genomic DNA was extracted from the complete body of individual fleas using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). PCRs were conducted using 25 µl reaction mixtures containing 10× Taq buffer with KCL (Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania), 25 mM MgCl2, 0.5 µl of dNTPs (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA), 0.25 µl of each primer, 0.1 µl of Taq DNA Polymerase (Fermentas) and 2 µl of genomic DNA. The primers used to amplify ~445-bp fragment of the 28S rRNA gene were 28S-1 (5ʹ-ATA CGC CTT CGG CTT ATG CG-3ʹ) and 28S-2 (5ʹ-AAT AAG ACG CCC CGG GAT TG-3ʹ) [26], while the primers used to amplify ~615-bp fragment of the cox2 gene were COII-2a (5ʹ-ATA GAK CWT CYC CHT TAA TAG AAC A-3ʹ) and COII-9b (5’-GTA CTT GCT TTC AGT CAT CTW ATG-3ʹ) [27]. PCRs were conducted using the following conditions: 96 °C for 5 min followed by 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s, and a final extension step at 72 °C for 5 min. Amplicons were purified [28] and subjected to automated DNA sequencing. The DNA sequences of representative samples for each gene have been deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers MT470834 and MT471346.

DNA extraction and PCR for Bartonella

DNA was extracted from pooled fleas corresponding to individual nests, dens, and geese and from fox blood clots using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit from Qiagen (Table 1). Conventional (450–720 bp) as well as real-time qPCR (95–125 bp) targeting the 16S-23S rRNA intergenic transcribed spacer (ITS) region of Bartonella spp. was performed as previously described [6, 29]. For conventional PCR, screening of the Bartonella ITS region was performed using oligonucleotides 325s (5’-CTT CAG ATG ATG ATC CCA AGC CTT CTG GCG-3’) and 1100as (5ʹ-GAA CCG ACG ACC CCC TGC TTG CAA AGC A-3ʹ) as forward and reverse primers, respectively. Amplification was performed in a 25-µl final volume reaction containing 12.5 µl of Tak-Ex® Premix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA), 0.25 µl of 30 µM of each forward and reverse primer (IDT® DNA Technology, Coralville, USA), 8 µl of molecular grade water, and 5 µl of DNA from each sample tested. PCR negative controls were prepared using 5 µl of DNA from blood of a healthy dog. Positive controls were prepared using 5 µl of genomic DNA from B. henselae SA2 (stock 0.001 pg/ µl). Conventional PCR was performed under the following conditions: 95 °C for 2 min followed by 55 cycles of 94 °C for 15 s, 66 °C for 15 s, 72 °C for 18 s, and a final extension step at 72 °C for 1 min. Products were analyzed by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and then sequenced to establish species strain identification.

For real-time qPCR, oligonucleotides 325s (5’- CTT CAG ATG ATG ATC CCA AGC CTT CTG GCG-3’) and 543as (5’-AAT TGG TGG GCC TGG GAG GAC TTG-3’) were used as forward and reverse primers and oligonucleotide BsppITS438probe (5’-FAM-GGT TTT CCG GTT TAT CCC GGA GGG C-BHQ1-3’) as Taqman probe. Amplification was performed in a 25-µl final volume reaction containing 12.5 µl of SsoAdvanced™ Universal Probes Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA), 0.2 µl of 100 µM of each primer and probe (IDT® DNA Technology), 7.5 µl of molecular-grade water, and 5 µl of DNA from each sample tested. PCR negative controls were prepared using 5 µl of DNA from blood of a healthy dog. Positive controls were prepared by using 5 µl of DNA from a serial dilution (using dog blood DNA) of B. henselae genomic DNA equivalent to 0.1, 0.01 and 0.001 pg/ µl. Quantitative PCR was performed in CFX96® (Bio-Rad) under the following conditions: 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 45 cycles of 94 °C for 10 s, 68 °C for 10 s, 72 °C for 10 s, and a final extension step at 72 °C for 30 s. Positive amplification was assessed by analysis of detectable fluorescence vs cycle values and positive products were sent for sequencing to establish species strain identification.

Results

There were no significant morphological differences between fleas collected from nests, dens, and geese. Amplicons of the expected size were obtained for all flea and blood samples subjected to PCR, whereas no products were obtained for the negative control samples. DNA sequences of part (436 bp) of the 28S rRNA gene were obtained for three flea specimens originating from dens and nests. There was no intraspecific variation in DNA sequence. These sequences were also 100% identical to the 28S sequences of C. petrochelidoni (GenBank: EU336152) and C. gallinae (GenBank: EU336148). The cox2 sequences (615 bp) obtained for two specimens of C. v. vagabundus (one from a den and one from a nest) were identical but differed at 18–41 bp (similarity of 94–97%) from the cox2 sequences of C. hirundinis, C. gallinae, C. petrochelidoni and C. rusticus (GenBank: KM8900834, KM8900832, AF424006 and KM8900836, respectively).

DNA from Bartonella spp. was amplified in 43% of pooled flea samples collected from individual nests (n = 16/37; 95% CI: 29–59%) and 40% of pooled flea samples from individual den sites (n = 2/5; 95% CI: 12–77%). Following sequencing, all Bartonella ITS amplicons from fleas collected in 2014 were identified as B. henselae (Table 2). Alignment analysis indicated that positive flea samples had 100% homology to B. henselae strain SA2 (GenBank: AF369529).

DNA extracted from fleas collected from harvested geese (9 Ross’s geese and 11 lesser snow geese) and blood clots from foxes failed to amplify on conventional PCR using primers targeting the entire ITS region. A qPCR targeting 150–220 bp of the ITS region amplified Bartonella spp. DNA in 5% of fox samples (n = 3/57; 95% CI: 2–14%) and 30% of pooled flea samples from geese (n = 6/20; 95% CI: 15–52%). This includes fleas from two Ross’s geese (n = 2/9; 95% CI: 6–55%) and four lesser snow geese (n = 4/11; 95% CI: 15–65%). Quantification cycle (Cq) values were in the range of 34.66–38.51. ITS amplicons from fleas were identified as B. vinsonii berkhoffii, exhibiting 100% homology to genotype II or IV. Unfortunately, the small size of the amplicon available for sequencing was not enough to differentiate among the two genotypes (DQ059763 and DQ059765). Similarly, blood samples from three foxes were positive for Bartonella via qPCR. The two positive samples collected in 2014 and 2016 were 98.8% homologous with the same Bartonella species detected in fleas (B. vinsonii berkhoffii DQ059763 and DQ059765). Meanwhile, a third fox blood sample from 2018 was positive, with 97.5% homology to B. rochalimae (GenBank: KU292577).

Discussion

This study verifies that Bartonella spp. circulate in the remote terrestrial ecosystem at Karrak Lake and suggests that nest fleas may serve as a potential vector for transmission between birds and mammals. As with previous studies, fleas collected from nests and geese were identified as C. v. vagabundus [16, 30]. Fleas collected from fox dens were also identified as C. v. vagabundus. Though all fleas were not individually identified in this study, the morphology, host, location, prior documentation at Karrak Lake, and relative scarcity of ectoparasites in the Arctic suggests that all specimens were most likely C. v. vagabundus. cox2 sequences for two fleas (one from a den and one from a nest) were identical, indicating that fleas may transfer from geese or nests to foxes during foraging efforts [15]. Ceratophyllus spp. have sporadically been reported on domestic dogs [31, 32], but this is the first report of a Ceratophyllus species in the dens of arctic foxes.

Fleas were found on geese that were shot on the southern border of the colony during arrival in spring, suggesting that this host-parasite relationship facilitates the transport and transmission of nest fleas and associated pathogens through Arctic terrestrial ecosystems. The known range for C. v. vagabundus is limited to the Arctic, and fleas found on geese may have originated from southern parts of Nunavut [24]. Over the last few decades, there has been a contemporaneous exponential growth in continental population size of both snow and Ross’s geese that nest at Karrak Lake [19]. This surge in abundance of migrating geese affects nest density in the colony, which may increase transmission of nest parasites between geese by decreasing distance between hosts [16]. These characteristics highlight the role of migratory geese in the dissemination of flea-borne pathogens during migration and nesting.

Fleas collected from dens and goose nests during the study contained B. henselae DNA, which suggests that previous reports by Mascarelli et al. [13] of B. henselae in arctic foxes from Karrak Lake may have resulted from a transient infestation with nest fleas or exposure to flea feces during nest predation (Fig. 2). However, it is important to note that detection of Bartonella DNA in fleas does not provide definitive proof of vector competence, as arthropods may have ingested blood meals from infected hosts. Thus, directionality of transmission could not be determined (fleas and/or flea dirt may infect foxes, foxes may infect fleas, or both). Subsequent studies are needed to address this question. For example, blood-meal composition and the presence or absence of Bartonella DNA in flea feces on the surface of eggs would provide vital information about feeding habits and the potential for transmission during predation.

Hypothesized mechanisms of Bartonella transmission in a terrestrial Arctic ecosystem. a Goose carcasses that are brought to dens may expose fox adults and kits to infected fleas. b Migrating geese may introduce Bartonella species from southern latitudes to fleas overwintering in nest material in the Arctic. Alternatively, nest fleas may expose geese to Bartonella if the bacteria can be maintained over the harsh arctic winter. c Collecting and caching eggs may result in transmission of Bartonella to foxes via nest flea bites or exposure to flea dirt on the surface of eggs. Alternatively, fleas may collect infected blood meals from foxes. d Predation of Arctic rodents may expose foxes to rodent fleas carrying Bartonella species. e Rodents may visit newly abandoned nests to consume egg remnants and may expose nest fleas to Bartonella species. Rodents may also be exposed to Bartonella species via flea feces or bites in nests

DNA of B. vinsonii berkhoffii was detected in fleas from 30% of infested geese. This species of Bartonella has been implicated in cases of clinical bartonellosis in dogs and evidence of infection has been found in a range of wild canids [33, 34]. Cq values were high (ranging from 34.66 to 38.51), indicating that the concentration of bacterial DNA was relatively low and that bacteremic blood may have been ingested long before fleas were collected. Prevalence of Bartonella spp. in fleas from nests and geese (43% for B. henselae and 30% for B. vinsonii berkhoffii) was high in relation to foxes (4% for B. vinsonii berkhoffii and 2% for B. rochalimae in the present study; 11% for B. henselae in Mascarelli et al. [13]), suggesting that fleas are likely to (i) be a competent vector or (ii) have frequent access to blood meals from a competent host. Experimental studies to document vector competence are required to distinguish between these two possibilities. Future work could determine whether DNA of Bartonella spp. is present in the blood and spleens of geese at Karrak Lake, as they provide the majority of the blood meals for the fleas.

The overall prevalence of Bartonella spp. DNA in arctic foxes was 5%, with all foxes exhibiting low levels of bacteremia (Cq values from 36.88 to 38.28). This suggests that the animals could have been sampled at a later stage of infection, consistent with exposure during the prior summer when vectors were active. Sequence analyses suggested that two species of Bartonella are present in this population: B. vinsonii berkhoffii (in two foxes) and B. rochalimae (in a single fox). These results, along with the study by Mascarelli et al. [13], verify that the same species of Bartonella are present in foxes and nest fleas (B. henselae and B. vinsonii berkhoffii) and supports the hypothesized mechanism of transmission between foxes and fleas during predation. The prevalence of Bartonella spp. in foxes suggests that they are unlikely to be maintenance hosts and that nest fleas may acquire blood meals from a more competent host species. However, it is important to note that adult foxes in this study were sampled in May before temperatures increased and that the prevalence in foxes may differ during months with peak insect activity. The detection of B. rochalimae in foxes may suggest that Arctic rodents and their associated fleas also play a role in the transmission of Bartonella above the treeline, as B. rochalimae DNA has been documented in rodents and gray foxes (Fig. 2) [35, 36]. Fleas have not been detected on adult arctic foxes during the month of May, and further studies could determine ectoparasite abundance and prevalence of Bartonella spp. in juvenile foxes captured during the summer months when birds are nesting, and insects are active.

Fleas that exhibit generalist tendencies may harbour multiple species of Bartonella, and the detection of B. henselae and B. vinsonii berkhoffii in nest fleas suggests that co-infections may be possible [37]. Based on previous publications, coinfections may limit the detection of different species of Bartonella [6]. For example, when B. henselae is present in equal numbers to B. vinsonii, only B. henselae will be amplified to quantities that can be sequenced. Therefore, both species of Bartonella may have been present in 2014 and 2018. However, the concentration of B. henselae in 2014 may have masked the presence of B. vinsonii. Alternatively, this observation could result from variation in blood meals from infected hosts between years.

Manifestations of disease following Bartonella spp. infection in arctic foxes, and wildlife in general, are poorly understood. Infections with B. henselae, B. vinsonii berkhoffii and B. rochalimae in domestic canids can range from subclinical bacteremia to severe illness, including lymphadenomegaly and endocarditis [35, 38]. These pathogens can result in the development of vasoproliferative lesions in dogs [39], and foxes may present with similar clinical symptoms and pathogenesis. Species of Bartonella that were identified during this study have zoonotic potential and may be transmitted to people that are in close contact with fleas and foxes, such as hunters, trappers, and biologists [40, 41]. Bartonella spp. and other zoonoses may be especially relevant in the Arctic where hunting and trapping are integral to both the culture and economy [42, 43].

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that B. henselae, B. vinsonii berkhoffii and B. rochalimae are present in the Karrak Lake ecosystem. Our study suggests that migratory geese may play a role in the dissemination of flea-borne pathogens and that contact between foxes and nesting geese is likely to be involved in the transmission dynamics of Bartonella spp. in the Arctic. However, other sources of infection and the competence of C. v. vagabundus are unknown. Future studies may investigate flea blood-meal composition and the presence of Bartonella DNA in geese, flea feces on the surface of eggs, juvenile arctic foxes, and rodents. Addressing these questions will increase our understanding of the epidemiology of Bartonella spp. above the tree line, the role of migratory wildlife in the movement of pathogens, and the vulnerability of northern and remote regions to the emergence of vector-borne pathogens.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the Zenodo repository http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3905327. Representative newly generated sequences were deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers MT470834 and MT471346.

References

Dehio C. Molecular and cellular basis of Bartonella pathogenesis. Ann Rev Microb. 2004;58:365–90.

Boulouis HJ, Chang CC, Henn JB, Kasten RW, Chomel BB. Factors associated with the rapid emergence of zoonotic Bartonella infections. Vet Res. 2005;36:383–410.

Billeter SA, Levy MG, Chomel BB, Breitschwerdt EB. Vector transmission of Bartonella species with emphasis on the potential for tick transmission. Med Vet Entomol. 2008;22:1–15.

Kordick DL, Brown TT, Shin KO, Breitschwerdt EB. Clinical and pathological evaluation of chronic Bartonella henselae or Bartonella clarridgeiae infection in cats. J Clin Microb. 1999;37:1536–47.

Breitschwerdt EB, Kordick DL. Bartonella infection in animals: carriership, reservoir potential, pathogenicity, and zoonotic potential for human infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:428–38.

Maggi RG, Duncan AB, Breitschwerdt EB. Novel chemically defined liquid medium for the growth, as single or composed culture, and the primary isolation of Bartonella sp. from blood and body fluids. J Clin Microb. 2005;43:2651–5.

Biswas S, Rolain JM. Bartonella infection: treatment and drug resistance. Future Microbiol. 2010;5:1719–31.

Valentine KH, Harms CA, Cadenas MB, Birkenheuer AJ, Marr HS, Braun-McNeill J, et al. Bartonella DNA in loggerhead sea turtles. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:949–50.

Mascarelli PE, McQuillan M, Harms CA, Harms RV, Breitschwerdt EB. Bartonella henselae and B. koehlerae DNA in birds. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:490–2.

Angelakis E, Rolain JM, Raoult D, Brouqui P. Bartonella quintana in head louse nits. FEMS Immunol Med Microb. 2011;62:244–6.

Ellis BA, Rotz LD, Leake JAD, Samalvides F, Bernable J, Ventura G, et al. An outbreak of acute bartonellosis (Oroya fever) in the Urubamba region of Peru, 1998. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:344–9.

Williams HM, Dittmar K. Expanding our view of Bartonella and its hosts: Bartonella in nest ectoparasites and their migratory avian hosts. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:13.

Mascarelli PE, Elmore SA, Jenkins EJ, Alisauskas RT, Walsh M, Breitschwerdt EB, et al. Vector-borne pathogens in arctic foxes, Vulpes lagopus, from Canada. Res Vet Sci. 2015;99:58–9.

Chomel BB, Kasten RW, Floyd-Hawkins K, Chi B, Yamamoto K, Roberts-Wilson J, et al. Experimental transmission of Bartonella henselae by the cat flea. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1952–6.

Samelius G, Alisauskas RT. Foraging patterns of arctic foxes at a large arctic goose colony. Arcticulture. 2000;53:279–88.

Harriman VB, Alisauskas RT, Wobeser GA. The case of the blood-covered egg: ectoparasite abundance in an arctic goose colony. Can J Zool. 2008;86:959–65.

Oteo JA, Maggi RG, Portillo A, Bradley J, García-Álvarez L, San-Martín M, et al. Prevalence of Bartonella spp. by culture, PCR and serology, in veterinary personnel from Spain. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:553.

Kerbes RH, Meeres KM, Alisauskas RT, Caswell FD, Abraham KF, Ross RK. Surveys of nesting mid-continent lesser snow geese and Rossʼs geese in eastern and central arctic Canada, 1997–98. Can Wildl Serv Techn Rep Series. 2006;447:1–65.

Alisauskas RT, Leafloor JO, Kellett DK. Abundance of Ross’s geese and midcontinent snow geese with recommendations for future monitoring. In: Evaluation of special management measures for midcontinent lesser snow geese and Ross’s geese. Arctic Goose Joint Venture Special Publication. 2012. https://www.agjv.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/AGJV_SNOW_GOOSE_RPT_2012_FINAL-1.pdf. Accessed 9 May 2020.

Borchert JN, Eisen RJ, Holmes JL, Atiku LA, Mpanga JT, Brown HE, et al. Evaluation and modification of off-host flea collection techniques used in northwest Uganda: laboratory and field studies. J Med Entomol. 2012;49:210–4.

Ross MV, Alisauskas RT, Douglas DC, Kellett DK. Decadal declines in avian herbivore reproduction: density-dependent nutrition and phenological mismatch in the Arctic. Ecology. 2017;98:1869–83.

Bouchard E, Elmore SA, Alisauskas RT, Samelius G, Gajadhar AA, Schmidt K, et al. Transmission dynamics of Toxoplasma gondii in arctic foxes (Vulpes lagopus): a long term mark-recapture serologic study at Karrak Lake, Nunavut. J Wildl Dis. 2019;55:619–26.

Samelius G, Lariviere S, Alisauskas RT. Immobilization of arctic foxes with tiletamine hydrochloride and zolazepam hydrochloride (Zoletil®). Wildl Soc Bull. 2003;31:1–5.

Holland GP. The fleas of Canada, Alaska and Greenland (Siphonaptera). Mem Entomol Soc Can. 1985;130:3–632.

Lewis RE, Galloway TD. A taxonomic review of the Ceratophyllus Curtis, 1832 of North America (Siphonaptera: Ceratophyllidae: Ceratophyllinae). J Vector Ecol. 2001;26:119–61.

Thoroughgood J T, Armstrong JS, White B, Anstead CA, Galloway TD, Lindsay LR, et al. Molecular differentiation of four species of Oropsylla (Siphonaptera: Ceratophyllidae) using PCR-based single strand conformation polymorphism analyses and DNA sequencing. J Med Entomol. tjaa161.

Whiting MF. Mecoptera is paraphyletic: multiple genes and phylogeny of Mecoptera and Siphonaptera. Zool Scr. 2002;31:93–104.

Krakowetz CN, Lindsay LR, Chilton NB. Genetic variation in the mitochondrial 16S ribosomal RNA gene of Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae). Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:530.

Portillo A, Maggi R, Oteo JA, Bradley J, García-Álvarez L, San-Martín M, et al. Bartonella spp. prevalence (serology, culture, and PCR) in sanitary workers in La Rioja Spain. Pathogens. 2020;9:189.

Harriman VB, Alisauskas RT. Of fleas and geese: the impact of an increasing nest ectoparasite on reproductive success. J Avian Biol. 2010;41:573–9.

Bond R, Riddle A, Mottram L, Beugnet F, Stevenson R. Survey of flea infestation in dogs and cats in the United Kingdom during 2005. Vet Rec. 2007;160:503–6.

Beck W, Boch K, Mackensen H, Wiegand B, Pfister K. Qualitative and quantitative observations on the flea population dynamics of dogs and cats in several areas of Germany. Vet Parasitol. 2006;137:130–6.

Cockwill KR, Taylor SM, Philibert HM, Breitschwerdt EB, Maggi RG. Bartonella vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii endocarditis in a dog from Saskatchewan. Can Vet J. 2007;48:839–44.

Beldomenico PM, Chomel BB, Foley JE, Sacks BN, Baldi CJ, Kasten RW, et al. Environmental factors associated with Bartonella vinsonii subsp berkhoffii seropositivity in free-ranging coyotes from northern California. Vector Borne Zoon Dis. 2005;5:110–9.

Henn JB, Gabriel MW, Kasten RW, Brown RN, Koehler JE, MacDonald KA, et al. Infective endocarditis in a dog and the phylogenetic relationship of the associated “Bartonella rochalimae” strain with isolates from dogs, gray foxes, and a human. J Clin Microb. 2009;47:787–90.

Mardosaitė-Busaitienė D, Radzijevskaja J, Balčiauskas L, Bratchikov M, Jurgelevičius V, Paulauskas V. Prevalence and diversity of Bartonella species in small rodents from coastal and continental areas. Sci Rep. 2019;9:12349.

Maggi RG, Breitschwerdt EB. Potential limitations of the 16S–23S rRNA intergenic region for the molecular detection of Bartonella species. J Clin Microb. 2005;43:1171–6.

Álvarez-Fernández A, Breitschwerdt EB, Solano-Gallego L. Bartonella infections in cats and dogs including zoonotic aspects. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:624.

Beerlage C, Varanat M, Linder K, Maggi RG, Cooley J, Kempf VAJ, et al. Bartonella vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii and Bartonella henselae as potential causes of proliferative vascular diseases in animals. Med Microb Immunol. 2012;201:319–26.

Roux V, Eykyn SJ, Raoult D. Bartonella vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii as an agent of afebrile blood culture-negative endocarditis in a human. J Clin Microb. 2000;38:1698–700.

Chang CC, Chomel BB, Kasten RW, Tappero JW, Sanchez MA, Koehler JE. Molecular epidemiology of Bartonella henselae infection in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients and their cat contacts, using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and genotyping. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:1733–9.

Usher PJ. The Bankslanders: Economy and ecology of a frontier trapping community. 1971. https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/831/items/1.0104005. Accessed 9 May 2020.

Bromley RG. Characteristics and management implications of the spring waterfowl hunt in the western Canadian Arctic, Northwest Territories. Arctic. 1996;49:70–85.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dana Kellett, especially, for all her work with arranging logistical support and preparing for the Karrak Lake field seasons. The authors also thank Sasha Ross and Keaton Schmidt for assisting with fox trapping during the summers of 2016 and 2017.

Funding

This study was supported by NSERC Discovery Grant and Northern Research Supplement (NRS-2018-517969 and RGPIN-2018-04900), Northern Scientific Training Program, ArcticNet, and Polar Knowledge Canada (NST-1718-0012). The long-term research at Karrak Lake has been supported by Polar Continental Shelf Project, The Central and Mississippi Flyway Councils, Canadian Wildlife Service and Wildlife Research Division of Environment and Climate Change Canada, Arctic Goose Joint Venture, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Ducks Unlimited Canada, Delta Waterfowl, and the University of Saskatchewan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KJB collected blood samples from foxes and nest fleas from goose carcasses at Karrak Lake during the summer of 2018, analyzed and interpreted data relating to Bartonella prevalence in fleas and fox blood and led the writing of the manuscript. RGM performed conventional and qPCR on pooled flea samples and fox blood and assisted with analyzing and interpreting data relating to Bartonella prevalence. JG collected nest fleas from goose nests and fox dens at Karrak Lake during the summer of 2014. TDG morphologically identified nest fleas from 2014. NBC molecularly identified a subset of nest fleas from 2014 via PCR and interpreted sequence data from these fleas. RTA ensured compliance with permit requirements in the Queen Maud Gulf Migratory Bird Sanctuary and collected goose carcasses in 2018. GS assisted with the collection of blood samples from foxes during the summers of 2014–2018. EB collected blood samples from foxes at Karrak Lake during the summers of 2014–2015. EJJ guided study design, implementation, and writing. All authors contributed to writing and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Research was approved by the Government of Nunavut (fox permits 2014-029, 2015-019, 2016-015, 2017-009, and 2018-014; goose permits 2014-027 and 2018-015) and the University of Saskatchewan Animal Research Ethics Board (CofA 20090159 and 19990029) and adhered to the CCAC guidelines for humane animal use.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Buhler, K.J., Maggi, R.G., Gailius, J. et al. Hopping species and borders: detection of Bartonella spp. in avian nest fleas and arctic foxes from Nunavut, Canada. Parasites Vectors 13, 469 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04344-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04344-3