Abstract

Background

Itaconic acid is an unsaturated, dicarboxylic acid which finds a wide range of applications in the polymer industry and as a building block for fuels, solvents and pharmaceuticals. Currently, Aspergillus terreus is used for industrial production, with titers above 100 g L−1 depending on the conditions. Besides A. terreus, Ustilago maydis is also a promising itaconic acid production host due to its yeast-like morphology. Recent strain engineering efforts significantly increased the yield, titer and rate of production.

Results

In this study, itaconate production by U. maydis was further increased by integrated strain- and process engineering. Next-generation itaconate hyper-producing strains were generated using CRISPR/Cas9 and FLP/FRT genome editing tools for gene deletion, promoter replacement, and overexpression of genes. The handling and morphology of this engineered strain were improved by deletion of fuz7, which is part of a regulatory cascade that governs morphology and pathogenicity. These strain modifications enabled the development of an efficient fermentation process with in situ product crystallization with CaCO3. This integrated approach resulted in a maximum itaconate titer of 220 g L−1, with a total acid titer of 248 g L−1, which is a significant improvement compared to best published itaconate titers reached with U. maydis and with A. terreus.

Conclusion

In this study, itaconic acid production could be enhanced significantly by morphological- and metabolic engineering in combination with process development, yielding the highest titer reported with any microorganism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

More than 300 potential bio-based building blocks were selected from the U.S. Department of Energy according to criteria such as estimated processing costs, estimated selling price, and the technical complexity, to determine the most important chemicals that can be produced from biomass. In the top selection, nine belong to the group of organic acids [72], underlining the importance of this class of chemicals. One of these compounds is the unsaturated dicarboxylate itaconic acid. It was first described in 1837 [4] and primary reports about microbial production with Aspergillus itaconicus date back to 1931 [42]. Due to its two functional groups, radical polymerization of the methylene group and/or esterification of the carboxylic acid with different co-monomers is possible [59, 63, 67]. This leads to a wide range of applications in the paper, architectural, pharmaceutical, paint, lacquer, and medical industries [5, 6, 40, 43, 50, 55, 61, 71]. It can also be used as an intermediate for the production of 3-methyltetrahydrofuran, a potential biofuel with advantageous combustion properties [16]. Further, itaconate production by mammalian macrophages is reported, where it plays a key role in the human immune response [11, 57, 69], with possible applications as therapeutic agent for autoimmune diseases [2].

In spite of this wide variety of potential applications, the market size of itaconic acid in 2011 was relatively small, with 41,400 tons and a market value of $74.5 million [71]. This is caused by the relatively high price of approximately two dollars per kg and the availability of cheaper petro-based alternatives such as acrylic acid. Reduction of this price is, therefore, a major criterion for access to further markets. To be competitive against petro-based products, costs need to reduce to around $0.5 per kg [1]. Assuming that the price would decrease, itaconic acid has the possibility to replace acrylic acid in the production of poly(methyl methacrylate), the production of which is petroleum based with a market worth of $11 billion [39, 43, 59]. Since 1950, Aspergillus terreus is used for the industrial production of itaconate [59]. Charles Pfizer Co. was granted the first patent for the production of itaconate with the filamentous fungus A. terreus by submerged cultivation [37]. During the last decades, the responsible metabolic pathways and regulatory mechanisms of itaconate production in A. terreus were studied in detail [67]. Major advances were achieved through process development. This long history of optimization has enabled titers above 100 g L−1 and yields near the theoretical maximum at low pH, making A. terreus the current best production host for itaconate production [7, 29, 34, 49, 50, 53, 66]. However, despite the long history and experience, itaconate production in A. terreus remains challenging. A specific pellet growth form is required for high productivity [25, 39] and therefore, morphology has to be strictly controlled. A. terreus reacts very sensitively to certain medium impurities, which can induce mycelium formation and stop itaconate production [15, 48, 50]. Thus, medium must be pretreated to remove impurities from production medium, especially when using less pure industrial substrates such as molasses [38, 59]. Consequently, morphological control influences the manufacturing process tremendously, leading to increased operational costs and failed batches.

Besides A. terreus, numerous itaconate producers have been engineered in recent years, such as E. coli [26], A. niger [31], and C. glutamicum [60]. Besides these heterologous hosts, Ustilaginaceae like the pH-tolerant Ustilago cynodontis or the yeast-like Ustilago maydis are natural itaconate producers which have recently been engineered to higher efficiency [21, 24, 33, 75]. Among the Ustilaginaceae, U. maydis is the most studied species in the fields of plant pathogenicity, cell biology, and biotechnology [17, 18, 52, 68, 70]. The Ustilaginaceae produce a broad spectrum of interesting products such as organic acids [21, 24, 76], glycolipids [14, 58], polyols [21, 35], and enzymes [14]. This, along with their yeast-like growth, makes them attractive for biotechnological applications [21].

That said, certain stresses can induce filamentous growth in U. maydis [45, 54] but efficient itaconate production with this species is, at least at small scale, not coupled to a specific morphology. In wild-type U. maydis, itaconate production is induced by nitrogen limitation [74] and requires pH values above five [21]. Like in A. terreus, the genes encoding the itaconate production pathway in U. maydis are clustered and co-regulated [19, 53]. Considerable progress has been made in increasing the yield, titer, and rate of itaconate production in U. maydis and related species by metabolic engineering and process development. Geiser et al. [19] characterized the itaconate production pathway and identified an itaconate oxidase Cyp3, which produces the downstream product (S)-2-hydroxyparaconate. The disruption of this oxidase, and overexpression of the cluster-associated regulator Ria1, led to 4.5-fold increase in ITA production in U. maydis [18]. In U. vetiveriae, itaconate production from glycerol could be increased 2.5-fold by overexpression of ria1 or 1.5-fold by overexpression of the mitochondrial transporter mtt1 [75].

In another study, we could show that heterologous expression of the mitochondrial transporter MttA from A. terreus in U. maydis enables more efficient itaconate production than the native mitochondrial transporter [32]. Further, by deletion of fuz7 in U. cynodontis, a stable yeast-like growth could be established for several relevant itaconic acid production conditions [33]. This is especially favorable for large-scale fermentation [62]. Furthermore, with optimization of growth media and the fermentation process, such as pulsed fed-batch strategies, product titers can be significantly increased [20, 21]. This is especially effective when combined with in situ product removal approaches such as reactive extraction or calcium precipitation [23, 43, 46, 75].

These optimizations have individually made a significant impact on the efficiency of itaconate production in Ustilago. In this study, we consolidate several of these metabolic and bioprocess engineering strategies to achieve itaconate titers that surpass those currently achieved by any other host.

Results and discussion

Engineering of a marker-free U. maydis MB215 for enhanced itaconate production

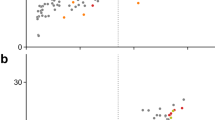

Previously, Geiser et al. [18] reached titers up to 63.2 ± 0.7 g L−1 with production rates up to 0.38 ± 0.00 g L−1 h−1 and a yield up to 0.48 ± 0.02 gITA g −1GLC in bioreactor experiments by deletion of the itaconate oxidase encoding cyp3 gene and overexpression of the gene encoding transcriptional regulator Ria1 (∆cyp3 Petef ria1). Unfortunately, two out of five possible antibiotic resistance markers available for U. maydis were genomically incorporated in this design, which limited further modification steps. Recently, Schuster et al. [65] established a CRISPR/Cas9 system for U. maydis enabling scarless and marker-free genome editing [12]. This technology, along with the FLP/FRT system for marker recycling already used in U. maydis [41] removes previous limitations of available antibiotic markers. We re-engineered the modifications described by Geiser et al. [18] using the CRISPR/Cas9 system from Schuster et al. [65]. To delete cyp3 and thereby abolis production of (S)-2-hydroxyparaconate, a repair template was used to delete the whole gene. It consisted of 1000 bp flanks homologous to sequences up- and downstream of cyp3. The overexpression of ria1 was not achieved by the in trans insertion of an expression cassette at the cbx locus, but rather by a direct in cis replacement of the native Pria1 promoter by the strong and constitutive Petef promoter. Here, the same strategy was chosen as for cyp3, including Petef between the flanks of the repair templates. Promoter exchanges were previously shown to effectively upregulate native genes [20]. Two chosen transformants of the resulting strain (∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef #1 and ∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef #2) were compared to the control strain from Geiser et al. [18] in System Duetz® 24-well plates [13], in screening medium with 50 g L−1 glucose, buffered either with 30 mM MES or 33 g L−1 CaCO3 (Fig. 1). As expected, itaconate production was lower using 30 mM MES compared to 33 g L−1 CaCO3, since U. maydis prefers pH values above 5 [21]. In both tested conditions, the transformants showed no difference to the control except for one notable exception. Itaconate concentrations in the cultures with the ∆cyp3 Petefria1 strain decreased markedly at 96 h with 30 mM MES (Fig. 1a). This rapid decrease shows that U. maydis can degrade itaconate, likely through a similar pathway as that described for A. terreus [10, 18]. Possibly, the expression of the genes encoding this degradation pathway is affected by the promoter replacement which removed the native Pria1 promoter. For further investigations, we selected the strain U. maydis ∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef #2.

Itaconate production and growth of engineered U. maydis strains. Itaconate concentration (a), growth (OD600, b), pH (c) and DIC images at an magnification of 630× (d–i) with ∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef #1 (green, filled inverted triangle) and ∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef #2 (black, filled circle) in comparison to ∆cyp3 Petefria1 (red, filled diamond) during shake flask cultivation in screening medium with 30 mM MES (open symbols) or 33 g L−1 CaCO3 (filled symbols) with 50 g L−1 glucose. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean (n = 3)

In the cultures of these overproducing strains, we also observed a degree of filamentous growth. Although this is by far not as prominent as described for U. cynodontis [33], elongated cells and filaments were formed in all tested U. maydis strains for all conditions shown in Fig. 1, especially upon addition of CaCO3.

Morphological engineering in U. maydis ∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef

Usually, filamentous growth in U. maydis is investigated in terms of pathogenicity. In its natural habitat, filamentous growth is indispensable to U. maydis for infection of Zea mays. This is strongly coupled with sexual development including a complex regulatory system [36, 51, 52]. Filamentous growth can also occur in haploid cells when they encounter stresses such as low pH, nitrogen limitation, or the presence of sunflower oil [45, 56]. This ability to grow filamentously is an obstacle in a biotechnological context, as it strongly influences bioprocess parameters such as oxygen transfer, viscosity, and clogging, and it increases the sensitivity to hydro-mechanical stress [44]. To solve this problem and to restore robust yeast-like growth, the fuz7 gene was deleted in the marker-free ∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef #2 strain by replacement with a hygromycin marker through homologous recombination, followed by FLP/FRT-mediated marker excision [41]. Fuz7 is part of the Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, which plays an important role in conjugation tube formation and filamentous growth [3]. By deletion of fuz7 in the strongly filamentous U. cynodontis, filamentous growth was repressed without influencing itaconate production and cell fitness under biotechnologically relevant conditions [33]. Deletion of fuz7 in U. maydis is known to abolish filamentous growth, and it also renders the strain completely apathogenic [3, 45]. This inability to colonize the maize plant is an additional advantage in a biotechnological context, as it may alleviate possible regulatory hurdles for industrial application.

To assess the effect of fuz7 deletion, cultivation studies in screening medium with 30 mM and 100 mM MES, and 33 g L−1 CaCO3, were performed (Fig. 2). As expected, U. maydis ∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef ∆fuz7 grew completely yeast-like in all tested conditions. In contrast, U. maydis ∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef grew filamentously (Fig. 2c), resulting in extensive adherence to the walls of the culture plates (Fig. 2d). This striking difference in morphology in the fuz7 mutant greatly improves handling of these cultures, while it did not negatively affecting itaconate production. Rather, production was significantly better at the end of cultivation for 30 mM and 100 mM MES.

Itaconate production and growth of morphology-engineered U. maydis strains. U. maydis ∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef (black, da1–6, b1–3) and U. maydis ∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef ∆fuz7 (blue, dc1–6, d1–3). Itaconate concentration (a), pH course (b), DIC images at a magnification of 630 (c) and a 24 well plate during System Duetz® cultivation in screening medium with 30 mM MES (open circle, da1–3+c1–3), 100 mM MES (circle with upper half filled, da4–6+c4–6) and 33 g L−1 CaCO3 (filled circle, db1–3+d1–3) and 50 g L−1 glucose. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean (n = 3)

Mitochondrial transporter engineering in U. maydis ∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef ∆fuz7

Recently, we could show by complementation experiments that overexpression of the mitochondrial transporter encoded by mttA from A. terreus enables higher itaconate production in U. maydis than overexpressing the native mtt1 [32]. Thus, to further increase itaconate production, we expressed mttA of A. terreus in U. maydis ∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef. ∆fuz7 using plasmid pETEF_CbxR_At_mttA [32]. The best of three individual transformants was selected for further study. Upon cultivation of this transformant with CaCO3, a white precipitate was observed in samples of these cultures, indicating that the solubility limit of calcium itaconate was reached. As described for malic acid production with U. trichophora, and itaconate production with U. vetiveriae, calcium salts of these organic acids have a lower solubility, leading to in situ precipitation in cultures where high titers are reached, usually preceded by a transient supersaturation of the product [75, 77]. To assess the effect of in situ itaconate precipitation in the engineered U. maydis strains, they were cultivated in System Duetz® plates in screening medium with 100 g L−1 glucose and 66 g L−1 CaCO3. Samples were analyzed with and without HCl treatment to re-solubilize the precipitated Ca-itaconate (Fig. 3). With the higher glucose concentration, the difference between strains with and without fuz7 deletion becomes more apparent, with the filamentous strains having a lower substrate uptake rate and a residual glucose concentration between 33.1 ± 2.6 and 38.2 ± 2.9 g L−1. Consequently, the strain with fuz7 deletion reached higher final titers, with U. maydis ∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef ∆fuz7 PetefmttA producing 33.6 ± 1.6 L−1 itaconate, which is 1.2-fold more than its predecessor ∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef ∆fuz7. This experiment indicates a solubility of Ca-itaconate of 14.5 ± 0.6 g L−1 under the tested conditions, estimated from the endpoint aqueous concentrations of cultures shown in Fig. 3d, e. This value is below the measured itaconate concentrations of some samples from the abovementioned cultures (Fig. 2), indicating that these samples were in the supersaturation state and that some product may have been overseen due to precipitation.

Comparison of aqueous and total itaconate concentrations in cultures of engineered U. maydis strains. Itaconate production (filled circle), glucose consumption (filled square) and macroscopic image of a 24-well plate after 96 h (f) of U. maydis ∆cyp3 Petefria1 (a, f(a1–3)), ∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef (b, f(a4–6)), ∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef ∆fuz7 (c, f(b1–3)) and ∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef ∆fuz7 PetefmttA (d, f(b4–6)) during System Duetz® cultivation in screening medium with 66 g L−1 CaCO3 and 100 g L−1 glucose. Dotted lines represent samples treated with HCl and continuous lines represents untreated supernatant samples. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean (n = 3). Glucose values were combined for untreated and treated samples (n = 6)

An even more pronounced effect was observed with similar cultures using glycerol as C-source (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). Glycerol is a very poor substrate for wild-type U. maydis MB215 [77], and it invokes a high degree of filamentation and pigmentation in U. cynodontis [33]. The fuz7 deletion had a very positive effect on the glycerol uptake rate and itaconate production, with the ∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef ∆fuz7 strain producing 13.1 ± 0.04 g L−1, compared to 4.3 ± 0.4 g L−1 produced by the ∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef control strain. Titers could be further increased with U. maydis ∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef ∆fuz7 PetefmttA to 16.1 ± 0.4 g L−1 itaconate.

Optimized itaconate production in a stirred bioreactor

In principle, the alleviation of product inhibition provided by the in situ precipitation of calcium itaconate enables much more extended cultures. In such cultures, productivity is only limited by the availability of the substrate and the stability of the biocatalyst. Therefore, to achieve high itaconate production, U. maydis MB215 ∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef ∆fuz7 PetefmttA was cultivated in pulsed fed-batch fermentations with CaCO3 in controlled 2-L bioreactors. The batch phase was started in screening medium containing 50 g L−1 glucose and 1.6 g L−1 NH4Cl (Fig. 4). The CaCO3 was added manually whenever pH dropped below 6.2, in the first 313 h as liquid suspension and after 313.5 h as a powder. Glucose was also pulsed into the fermenter to keep the concentration above 20 g L−1. The feeding schedule of CaCO3 and glucose is given in Additional file 1: Table S1. The resulting titer of 140 g L−1 itaconate was reached after 437 h. This is 2.2-fold more than the best published 63.2 ± 0.7 g L−1 from Geiser et al. [18] with U. maydis. Biomass formation mainly occurred in the first 72 h and reached OD600 values around 90, varying between 80 and 110 for the rest of the fermentation. These variations are likely due to analytical errors caused by CaCO3 precipitation upon sampling and OD measurement. An overall yield of 0.39 gITA g −1GLC was reached and the overall productivity was 0.32 g L−1 h−1, with a maximum productivity between 24 and 120 h of 0.65 g L−1 h−1, after which it stayed relatively linear at 0.23 g L−1 h−1. This decrease in productivity might be caused by the high solids load of 10–15% CaCO3 and Ca-itaconate in the fermentation broth, which could result in inhomogeneous mixing with pockets of low oxygen tension. For itaconate production, sufficient supply of oxygen is very important, with even transient oxygen limitations leading to a decrease of production [27, 44]. Future process development should, thus, focus on better mixing with these high solids loads, i.e., by changing stirrer geometry which can promote better oxygen distribution in viscous media [9]. In addition to itaconate, production of 31 g L−1 malate was also observed thereby increasing the total acid production to 170 g L−1 and the total acid yield to 0.48 gACID g −1GLC . This increased by-product formation could be the result of the additional supply of CO2 by CaCO3. The efficient microbial production of malate via pyruvate relies on CO2 as co-substrate [77], and the additional CO2 provided by the CaCO3 might imbalance the precursor supply of itaconate.

Controlled pulsed fed-batch fermentation of U. maydis MB215 ∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef ∆fuz7 PetefmttA in the presence of CaCO3. a Growth (filled triangle), and glucose concentration (filled square) and b: concentration of itaconate (filled inverted triangle), malate (open inverted triangle), and pH (continuous line) during a single representative bioreactor cultivation in batch medium with a starting concentration of 50 g L−1 glucose and 1.6 g L−1 NH4Cl. pH was kept above 6.2 by manual addition of CaCO3. Feeding schemes of glucose and CaCO3 are listed in Additional file 1: Table S1

In a similar approach where pH was controlled by titration with NaOH, a much lower level of itaconate production was observed (Additional file 1: Fig. S2), reaching a maximum titer of only 35.9 ± 1.5 g L−1 with a yield of 0.2 ± 0.01 gITA g −1GLC and an overall productivity of 0.12 ± 0.004 g L−1 h−1. In this titrated fermenter less than 1 g L−1 malate was produced, supporting the hypothesis that the additional CO2 from CaCO3 increases malate production. The overall decrease of productivity in the titrated culture is likely caused by the overexpression of mttA, which significantly stresses the cells leading to reduced growth and productivity as described previously [32]. The application of in situ itaconate crystallization with CaCO3, greatly reduced product inhibition, which is especially relevant with this deeply engineered strain, leading to almost threefold higher production rates.

To further improve the production rate, the cell density was increased by increasing the NH4Cl concentration to 4 g L−1 and the starting glucose concentration to 200 g L−1 (Fig. 5). A similar feeding strategy of glucose and CaCO3 as above was applied (Additional file 1: Table S2). As expected, higher biomass formation was observed with the higher ammonium concentration, although the 2.5-fold higher nitrogen concentration only led to a moderate increase of the OD600 to around 110. A similar trend was observed with A. terreus, where a fourfold increase in phosphate as the growth-limiting nutrient only led to a twofold increase in biomass [48]. In spite of this, the overall production rate was increased significantly to 0.45 g L−1 h−1. The higher overall production rate was also reflected in a higher maximum rate of 0.74 g L−1 h−1 between 24 and 189 h followed by a fairly linear rate of 0.35 g L−1 h−1 for the rest of the fermentation. This higher rate enabled the production of 220 g L−1 itaconate and 28 g L−1 malate resulting in a total acid titer of 248 g L−1 in the same timeframe as the lower density culture. Of this total titer, approximately 14 g L−1 of each acid will be dissolved in the aqueous phase [77], with a further 287 g L−1 occurring as solid calcium salts. Occasional spikes in the measured itaconate concentration can be observed, likely due to the re-dispersion of Ca-itaconate clumps from the headspace into the broth. Indeed, extensive clumping could be observed owing to the very high solid loads of 20–35%. As expected, the higher rates come at a cost of a yield reduction to 0.33 gITA g −1GLC and a total acid yield of 0.37 gACID g −1GLC , as more glucose is consumed for biomass production and maintenance.

Controlled high-density pulsed fed-batch fermentation of U. maydis MB215 ∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef ∆fuz7 PetefmttA in the presence of CaCO3. a Growth (filled triangle), and glucose concentration (filled square) and b concentration of itaconate (filled inverted triangle), malate (open inverted triangle), and pH (continuous line) during a single representative bioreactor cultivation in batch medium with a starting concentration of 200 g L−1 glucose and 4 g L−1 NH4Cl. The pH was kept above 6.2 by manual addition of CaCO3. Feeding schemes of glucose and CaCO3 are listed in Additional file 1: Table S2

Conclusion

In this study, the combination of metabolic and morphological engineering together with in situ crystallization of itaconate yielded a titer of 220 g L−1 itaconate, which corresponds to 284 g L−1 calcium itaconate. This titer exceeds the 160 g L−1 achieved with A. terreus [48], although the yield and production rate achieved with A. terreus are still higher [50]. Especially, the yield achieved with U. maydis could be further increased by the reduction of byproduct formation, as illustrated by the relatively high levels of malate production under these conditions. The strategy of in situ crystallization has not been reported in a biotechnological context with A. terreus, likely because the used pH values and the presence of solids strongly affect its morphology [48]. The use of in situ crystallization greatly enhanced itaconate production, but it will also pose new bioprocessing challenges such as solid/solid separation of biomass, CaCO3 and Ca-itaconate, or pH shifts for resolubilization of itaconate prior to purification [47, 62]. In all, this study demonstrates the power of an integrated approach of strain and process engineering by greatly enhancing Ustilago-based itaconate production.

Materials and methods

Media and culture conditions

All strains used in this thesis are listed in Table 1. E. coli strains were grown in medium containing 10 g L−1 peptone, 5 g L−1 sodium chloride, 5 g L−1 yeast extract, and 5 g L−1 glucose. U. maydis strains were grown in YEPS medium containing, 10 g L−1 yeast extract, 10 g L−1 peptone, and 10 g L−1 sucrose. Growth and production experiments were performed using screening medium according to Geiser et al. [21] with varying glucose concentrations, C-sources (glycerol/glucose), and various buffer concentrations of 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid (MES) and 33 g L−1 CaCO3. This medium further contained 0.8 g L−1 NH4Cl, 0.2 g L−1 MgSO4·7H2O, 0.01 g L−1 FeSO4·7H2O, 0.5 g L−1 KH2PO4, 1 mL L−1 vitamin solution, and 1 mL L−1 trace element solution. The vitamin solution contained (per liter) 0.05 g d-biotin, 1 g d-calcium pantothenate, 1 g nicotinic acid, 25 g myo-inositol, 1 g thiamine hydrochloride, 1 g pyridoxol hydrochloride, and 0.2 g para-aminobenzoic acid. The trace element solution contained (per liter) 15 g EDTA, 0.45 g of ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.10 g of MnCl2·4H2O, 0.03 g of CoCl2·6H2O, 0.03 g of CuSO4·5H2O, 0.04 g of Na2MoO4·2H2O, 0.45 g of CaCl2·2H2O, 0.3 g of FeSO4·7H2O, 0.10 g of H3BO3 and 0.01 g of KI. Shaking cultures of U. maydis and mutants strains were performed in System Duetz® (24 well plates) with a filling volume of 1.5 mL (d = 50 mm, n = 300 rpm, T = 30 °C and Φ = 80%) or in 500 mL shaking flasks with a filling volume of 50 mL (d = 25 mm, n = 200 rpm, T = 30 °C and Φ = 80%) [13]. If System Duetz® was used, cultures were parallelly inoculated into multiple plates and for each sample point, and a complete plate was taken as sacrificial sample to ensure continuous oxygenation.

Controlled batch cultivations were performed in a New Brunswick BioFlo® 115 bioreactor (Eppendorf, Germany) with a total volume of 1.3 L and a working volume of 0.5 L or a total volume of 2.0 L and a starting volume of 1.0 L if CaCO3 was used. All cultivations were performed in batch medium containing 0.2 g L−1 MgSO4·7H2O, 0.01 g L−1 FeSO4·7H2O, 0.5 g L−1 KH2PO4, 1 g L−1 yeast extract (Merck Millipore, Germany) 1 mL L−1 vitamin solution, and 1 mL L−1 trace element solution and varying concentrations of glucose and NH4Cl as indicated. During cultivation, pH 6.0 was maintained by automatic addition of 10 M NaOH or pH was kept above 6.2 by manual addition of CaCO3. The stirring rate was kept constant at 1000 rpm with 2 Rushton impeller. The bioreactor was aerated with an aeration rate of 1 L min−1 (2 vvm) for working volume of 0.5 L or 2 L min−1 (1 vvm) for total volume of 2 L, while evaporation was limited by sparging the air through a water bottle. The temperature was set at 30 °C. The bioreactor was inoculated to a final OD600 of 0.75 with cells from an overnight culture in 50 mL screening medium containing 50 g L−1 glucose and 100 mM MES buffer.

Analytical methods

When using CaCO3 as buffer, 1 mL of culture broth was taken for OD600 determination and HPLC analysis. The CaCO3 was dissolved with HCL prior to further measurements, basically as described by Zambanini et al. [77].

Cell densities were measured by determining the absorption at 600 nm with an Ultrospec 10 Cell Density Meter (Amersham Biosciences, Chalfont St Giles, UK).

For CDW determination of controlled high-density pulsed fed-batch fermentation of U. maydis MB215 ∆cyp3 ∆Pria1::Petef ∆fuz7 PetefmttA with NaOH titration 1 mL culture broth was centrifuged at maximum speed (Heraeus Megafuge 16R, TX-400 rotor, Thermo Scientific) and the pellet was dried (Scan Speed 40 lyophilizer, Labogene ApS) for 24 h at 38 °C and weighed afterwards.

Off-gas analysis for online monitoring of CO2 content were performed with BCpreFerm sensors (BlueSens gas sensor GmbH).

Differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy was performed with a Leica DM500 light microscope (Leica Microsystems). Images were recorded with a Leica ICC50 digital microscope camera (Leica Microsystems). Images were taken at 630-fold magnification. The cell morphology was analyzed by microscopy at different time points in all cultivations.

The ammonium concentration in the culture supernatant was measured by a colorimetric method according to Willis et al. [73] using salicylate and nitroprusside.

Products in the supernatants were analyzed in a DIONEX UltiMate 3000 High-Performance Liquid Chromatography System (Thermo Scientific, Germany) with an ISERA Metab AAC column 300 × 7.8 mm column (ISERA, Germany). As solvent, 5 mM H2SO4 with a flow rate of 0.6 mL min−1 and a temperature of 40 °C was used. Samples were filtered with Rotilabo® (CA, 0.20 µm, Ø 15 mm) or Acrodisc® (GHP 0.20 µm, Ø 13 mm) syringe filters and afterwards diluted up to 1:30 with 5 mM H2SO4. Itaconate and malate were determined with a DIONEX UltiMate 3000 Variable Wavelength Detector set to 210 nm, and glucose with a refractive index detector SHODEX RI-101 (Showa Denko Europe GmbH, Germany). Analytes were identified via retention time and UV/RI quotient compared to corresponding standards. All values are the arithmetic mean of at least three biological replicates instead of CaCO3 fermentations (n = 1). Error bars indicate the deviation from the mean for n = 2, if n > 2 error bars indicate the standard error of the mean. Statistical significance was assessed by t-test (two-tailed distribution, heteroscedastic, p ≤ 0.05).

Plasmid cloning and strain engineering

Plasmids were assembled by Gibson assembly [22] using the NEBbuilder HiFi DNA Assembly kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). Primers were ordered as unmodified DNA oligonucleotides from Eurofins Genomics (Ebersberg, Germany). As polymerase, Q5 High-Fidelity Polymerase was used. Detailed information about utilized primers and plasmid are listed in Additional file 1: Table S3 and S4. All assembled plasmids were subcloned into E. coli 10β from New England Biolab and confirmed by PCR, restriction or sequencing. Standard cloning techniques for E. coli were performed according Sambrook et al. [64]. For transformation, preparation of protoplasts and isolation of genomic DNA of U. maydis protocols according to Brachmann et al. [8] were used. For deletion of fuz7 in U. maydis, homologous recombination with 1000 bp flanking regions (F1, F2) including FRT sites and a hygromycin resistance cassette were used. For integration of pETEF_CbxR_At_mttA [32], the plasmid was linearized with SspI and integrated into the genome. For exchange of the promoter of ria1, CRISPR/Cas9 system was used according to Schuster et al. [65] and sgRNA has been selected online with http://www.e-crisp.org/E-CRISP/ [28]. A donor template was used to exchange the native promoter with the strong and constitutive Petef. Successful integration and deletion were verified by PCR and sequencing.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CRISPR:

-

clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats

- FLP/FRT:

-

flippase-mediated recombination

- pH:

-

potential hydrogen

- ITA:

-

itaconic acid

- GLC:

-

glucose

- HCl:

-

hydrochloric acid

- Ca-itaconate:

-

calcium itaconate

- C-source:

-

carbon source

- h:

-

hour

- HPLC:

-

high performance liquid chromatography

- CDW:

-

cell dry weight

- UV/RI:

-

ultraviolet/refractive index

- PCR:

-

polymerase chain reaction

- A. terreus :

-

Aspergillus terreus

- E. coli :

-

Escherichia coli

- A. niger :

-

Aspergillus niger

- C. glutamicum :

-

Corynebacterium glutamicum

- U. maydis :

-

Ustilago maydis

- U. cynodontis :

-

Ustilago cynodontis

- U. vetiveriae :

-

Ustilago vetiveriae

- ria1 :

-

regulator of itaconic acid biosynthesis

- mtt1 :

-

mitochondrial transporter from Ustilago maydis

- mttA :

-

mitochondrial transporter from Aspergillus terreus

- fuz7 :

-

dual specificity protein kinase

- cyp3 :

-

oxidase encoding gene

- Pria1 :

-

native promoter of ria1

- Petef :

-

strong and constitutive promoter

- MES:

-

2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid

- OD:

-

optical density

References

Bafana R, Pandey RA. New approaches for itaconic acid production: bottlenecks and possible remedies. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2018;38:68–82.

Bambouskova M, Gorvel L, Lampropoulou V, Sergushichev A, Loginicheva E, Johnson K, Korenfeld D, Mathyer ME, Kim H, Huang LH, Duncan D, Bregman H, Keskin A, Santeford A, Apte RS, Sehgal R, Johnson B, Amarasinghe GK, Soares MP, Satoh T, Akira S, Hai T, de Guzman Strong C, Auclair K, Roddy TP, Biller SA, Jovanovic M, Klechevsky E, Stewart KM, Randolph GJ, Artyomov MN. Electrophilic properties of itaconate and derivatives regulate the IκBζ-ATF3 inflammatory axis. Nature. 2018;556:501–4.

Banuett F, Herskowitz I. Identification of Fuz7, a Ustilago maydis MEK/MAPKK homolog required for a-locus-dependent and-independent steps in the fungal life-cycle. Gene Dev. 1994;8:1367–78.

Baup S. Über eine neue Pyrogen-Citronensäure, und über Benennung der Pyrogen Säure überhaupt. Annales de Chimie et de Physique. 1837;19:29–38.

Bera R, Dey A, Chakrabarty D. Synthesis, characterization, and drug release study of acrylamide-co-itaconic acid based smart hydrogel. Polym Eng Sci. 2015;55:113–22.

Betancourt T, Pardo J, Soo K, Peppas NA. Characterization of pH-responsive hydrogels of poly(itaconic acid-g-ethylene glycol) prepared by UV-initiated free radical polymerization as biomaterials for oral delivery of bioactive agents. J Biomed Mater Res. 2010;93:175–88.

Bonnarme P, Gillet B, Sepulchre AM, Role C, Beloeil JC, Ducrocq C. Itaconate biosynthesis in Aspergillus terreus. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3573–8.

Brachmann A, Konig J, Julius C, Feldbrügge M. A reverse genetic approach for generating gene replacement mutants in Ustilago maydis. Mol Genet Genomics. 2004;272:216–26.

Buckland BC, Gbewonyo K, Dimasi D, Hunt G, Westerfield G, Nienow AW. Improved performance in viscous mycelial fermentations by agitator retrofitting. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1988;31:737–42.

Chen M, Huang X, Zhong C, Li J, Lu X. Identification of an itaconic acid degrading pathway in itaconic acid producing Aspergillus terreus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;100:7541–8.

Cordes T, Michelucci A, Hiller K. Itaconic acid: the surprising role of an industrial compound as a mammalian antimicrobial metabolite. Annu Rev Nutr. 2015;35:451–73.

Donohoue PD, Barrangou R, May AP. Advances in industrial biotechnology using CRISPR-Cas systems. Trends Biotechnol. 2018;36:134–46.

Duetz WA, Ruedi L, Hermann R, O’Connor K, Büchs J, Witholt B. Methods for intense aeration, growth, storage, and replication of bacterial strains in microtiter plates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:2641–6.

Feldbrügge M, Kellner R, Schipper K. The biotechnological use and potential of plant pathogenic smut fungi. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97:3253–65.

Gao Q, Liu J, Liu LM. Relationship between morphology and itaconic acid production by Aspergillus terreus. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;24:168–76.

Geilen FMA, Engendahl B, Harwardt A, Marquardt W, Klankermayer J, Leitner W. Selective and flexible transformation of biomass-derived platform chemicals by a multifunctional catalytic system. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:5510–4.

Geiser E, Hosseinpour Tehrani H, Meyer S, Blank LM, Wierckx N. Evolutionary freedom in the regulation of the conserved itaconate cluster by Ria1 in related Ustilaginaceae. Fungal Biol Biotechnol. 2018;5:14.

Geiser E, Przybilla SK, Engel M, Kleineberg W, Buttner L, Sarikaya E, Den Hartog T, Klankermayer J, Leitner W, Bölker M, Blank LM, Wierckx N. Genetic and biochemical insights into the itaconate pathway of Ustilago maydis enable enhanced production. Metab Eng. 2016;38:427–35.

Geiser E, Przybilla SK, Friedrich A, Buckel W, Wierckx N, Blank LM, Bölker M. Ustilago maydis produces itaconic acid via the unusual intermediate trans-aconitate. Microb Biotechnol. 2015;9:116–26.

Geiser E, Reindl M, Blank LM, Feldbrügge M, Wierckx N, Schipper K. Activating intrinsic carbohydrate-active enzymes of the smut fungus Ustilago maydis for the degradation of plant cell wall components. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82:5174–85.

Geiser E, Wiebach V, Wierckx N, Blank LM. Prospecting the biodiversity of the fungal family Ustilaginaceae for the production of value-added chemicals. Fungal Biol Biotechnol. 2014;1:2.

Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang RY, Venter JC, Hutchison CA, Smith HO. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods. 2009;6:343.

Gorden J, Geiser E, Wierckx N, Blank LM, Zeiner T, Brandenbusch C. Integrated process development of a reactive extraction concept for itaconic acid and application to a real fermentation broth. Eng Life Sci. 2017;17:809–16.

Guevarra ED, Tabuchi T. Accumulation of itaconic, 2-hydroxyparaconic, itatartaric, and malic-acids by strains of the genus Ustilago. Agric Biol Chem. 1990;54:2353–8.

Gyamerah M. Factors affecting the growth form of Aspergillus terreus NRRL 1960 in relation to itaconic acid fermentation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1995;44:356–61.

Harder BJ, Bettenbrock K, Klamt S. Model-based metabolic engineering enables high yield itaconic acid production by Escherichia coli. Metab Eng. 2016;38:29–37.

Hartmann SK, Stockdreher Y, Wandrey G, Hosseinpour Tehrani H, Zambanini T, Meyer AJ, Büchs J, Blank LM, Schwarzländer M, Wierckx N. Online in vivo monitoring of cytosolic NAD redox dynamics in Ustilago maydis. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2018;1859:1015–24.

Heigwer F, Kerr G, Boutros M. E-CRISP: fast CRISPR target site identification. Nat Methods. 2014;11:122.

Hevekerl A, Kuenz A, Vorlop KD. Influence of the pH on the itaconic acid production with Aspergillus terreus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:10005–12.

Hewald S, Josephs K, Bolker M. Genetic analysis of biosurfactant production in Ustilago maydis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:3033–40.

Hossain AH, Ter Beek A, Punt PJ. Itaconic acid degradation in Aspergillus niger: the role of unexpected bioconversion pathways. Fungal Biol Biotechnol. 2019;6:1.

Hosseinpour Tehrani H, Geiser E, Engel M, Hartmann SK, Hossain AH, Punt PJ, Blank LM, Wierckx N. The interplay between transport and metabolism in fungal itaconic acid production. Fungal Genet Biol. 2019;125:45–52.

Hosseinpour Tehrani H, Tharmasothirajan A, Track E, Blank LM, Wierckx N. Engineering the morphology and metabolism of pH tolerant Ustilago cynodontis for efficient itaconic acid production. Metab Eng. 2019;54:293–300.

Jaklitsch WM, Kubicek CP, Scrutton MC. The subcellular organization of itaconate biosynthesis in Aspergillus terreus. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:533–9.

Jeya M, Lee K-M, Tiwari MK, Kim J-S, Gunasekaran P, Kim S-Y, Kim I-W, Lee J-K. Isolation of a novel high erythritol-producing Pseudozyma tsukubaensis and scale-up of erythritol fermentation to industrial level. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;83:225–31.

Kahmann R, Kämper J. Ustilago maydis: how its biology relates to pathogenic development. New Phytol. 2004;164:31–42.

Kane JH, Finlay AC, Amann PF. Production of itaconic acid. Assignee: Pfizer Inc. Patent number: US2385283A, 1945.

Karaffa L, Diaz R, Papp B, Fekete E, Sandor E, Kubicek CP. A deficiency of manganese ions in the presence of high sugar concentrations is the critical parameter for achieving high yields of itaconic acid by Aspergillus terreus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99:7937–44.

Karaffa L, Kubicek CP. Citric acid and itaconic acid accumulation: variations of the same story? Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2019;103:2889–902.

Khalid SH, Qadir MI, Massud A, Ali M, Rasool MH. Effect of degree of cross-linking on swelling and drug release behaviour of poly(methyl methacrylate-co-itaconic acid) [P(MMA/IA)] hydrogels for site specific drug delivery. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2009;19:413–8.

Khrunyk Y, Munch K, Schipper K, Lupas AN, Kahmann R. The use of FLP-mediated recombination for the functional analysis of an effector gene family in the biotrophic smut fungus Ustilago maydis. New Phytol. 2010;187:957–68.

Kinoshita K. Über die Produktion von Itaconsäure und Mannit durch einen neuen Schimmelpilz. Acta Phytochim. 1932;5:271–87.

Klement T, Büchs J. Itaconic acid—a biotechnological process in change. Bioresour Technol. 2013;135:422–31.

Klement T, Milker S, Jager G, Grande PM, Dominguez de Maria P, Büchs J. Biomass pretreatment affects Ustilago maydis in producing itaconic acid. Microb Cell Fact. 2012;11:43.

Klose J, de Sa MM, Kronstad JW. Lipid-induced filamentous growth in Ustilago maydis. Mol Microbiol. 2004;52:823–35.

Kreyenschulte D, Heyman B, Eggert A, Maßmann T, Kalvelage C, Kossack R, Regestein L, Jupke A, Büchs J. In situ reactive extraction of itaconic acid during fermentation of Aspergillus terreus. Biochem Eng J. 2018;135:133–41.

Kristiansen B, Mattey M, Linden J, editors. Citric acid biotechnology. London: Taylor & Francis Ltd; 1999. ISBN 0-203-48339-1.

Krull S, Hevekerl A, Kuenz A, Pruss U. Process development of itaconic acid production by a natural wild type strain of Aspergillus terreus to reach industrially relevant final titers. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;101:4063–72.

Kuenz A, Gallenmuller Y, Willke T, Vorlop KD. Microbial production of itaconic acid: developing a stable platform for high product concentrations. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;96:1209–16.

Kuenz A, Krull S. Biotechnological production of itaconic acid-things you have to know. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;102:3901–14.

Lanver D, Müller AN, Happel P, Schweizer G, Haas FB, Franitza M, Pellegrin C, Reissmann S, Altmüller J, Rensing SA, Kahmann R. The biotrophic development of Ustilago maydis studied by RNA-seq analysis. Plant Cell. 2018;30:300–23.

Lanver D, Tollot M, Schweizer G, Lo Presti L, Reissmann S, Ma LS, Schuster M, Tanaka S, Liang L, Ludwig N, Kahmann R. Ustilago maydis effectors and their impact on virulence. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15:409–21.

Li A, van Luijk N, ter Beek M, Caspers M, Punt P, van der Werf M. A clone-based transcriptomics approach for the identification of genes relevant for itaconic acid production in Aspergillus. Fungal Genet Biol. 2011;48:602–11.

Lovely CB, Perlin MH. Cla4, but not Rac1, regulates the filamentous response of Ustilago maydis to low ammonium conditions. Commun Integr Biol. 2011;4:670–3.

Magalhaes AI, de Carvalho JC, Medina JDC, Soccol CR. Downstream process development in biotechnological itaconic acid manufacturing. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;101:1–12.

Martinez-Espinoza AD, Ruiz-Herrera J, Leon-Ramirez CG, Gold SE. MAP kinase and CAMP signaling pathways modulate the pH-induced yeast-to-mycelium dimorphic transition in the corn smut fungus Ustilago maydis. Curr Microbiol. 2004;49:274–81.

Michelucci A, Cordes T, Ghelfi J, Pailot A, Reiling N, Goldmann O, Binz T, Wegner A, Tallam A, Rausell A, Buttini M, Linster CL, Medina E, Balling R, Hiller K. Immune-responsive gene 1 protein links metabolism to immunity by catalyzing itaconic acid production. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:7820–5.

Morita T, Fukuoka T, Imura T, Kitamoto D. Production of glycolipid biosurfactants by basidiomycetous yeasts. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2009;53:39–49.

Okabe M, Lies D, Kanamasa S, Park EY. Biotechnological production of itaconic acid and its biosynthesis in Aspergillus terreus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;84:597–606.

Otten A, Brocker M, Bott M. Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for the production of itaconate. Metab Eng. 2015;30:156–65.

Ranjha NM, Mudassir J, Akhtar N. Methyl methacrylate-co-itaconic acid (MMA-co-IA) hydrogels for controlled drug delivery. J Solgel Sci Technol. 2008;47:23–30.

Regestein L, Klement T, Grande P, Kreyenschulte D, Heyman B, Maßmann T, Eggert A, Sengpiel R, Wang Y, Wierckx N, Blank LM, Spiess A, Leitner W, Bolm C, Wessling M, Jupke A, Rosenbaum M, Büchs J. From beech wood to itaconic acid: case study on biorefinery process integration. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2018;11:279.

Robert T, Friebel S. Itaconic acid—a versatile building block for renewable polyesters with enhanced functionality. Green Chem. 2016;18:2922–34.

Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular cloning a laboratory manual. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. ISBN 978-1-93-611342-2.

Schuster M, Schweizer G, Reissmann S, Kahmann R. Genome editing in Ustilago maydis using the CRISPR-Cas system. Fungal Genet Biol. 2016;89:3–9.

Steiger MG, Blumhoff ML, Mattanovich D, Sauer M. Biochemistry of microbial itaconic acid production. Front Microbiol. 2013;4:23.

Steiger MG, Wierckx N, Blank LM, Mattanovich D, Sauer M. Itaconic acid—an emerging building block, Chapter 15. In: Industrial biotechnology: products and processes. Hoboken: Wiley; 2016.

Steinberg G, Perez-Martin J. Ustilago maydis, a new fungal model system for cell biology. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:61–7.

Sugimoto M, Sakagami H, Yokote Y, Onuma H, Kaneko M, Mori M, Sakaguchi Y, Soga T, Tomita M. Non-targeted metabolite profiling in activated macrophage secretion. Metabolomics. 2012;8:624–33.

Vollmeister E, Schipper K, Feldbrügge M. Microtubule-dependent mRNA transport in the model microorganism Ustilago maydis. RNA Biol. 2012;9:261–8.

Weastra. Wp 8.1, determination of market potential for selected platform chemicals: itaconic acid, succinic acid, 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid. Technical report, Bioconsept. 2013.

Werpy T, Peterson G. Top value added chemicals from biomass. Volume 1—results of screening for potential candidates from sugars and synthesis gas. Washington: US-DoE; 2004.

Willis RB, Montgomery ME, Allen PR. Improved method for manual, colorimetric determination of total kjeldahl nitrogen using salicylate. J Agric Food Chem. 1996;44:1804–7.

Zambanini T, Hartmann SK, Schmitz LM, Büttner L, Hosseinpour Tehrani H, Geiser E, Beudels M, Venc D, Wandrey G, Büchs J, Schwarzländer M, Blank LM, Wierckx N. Promoters from the itaconate cluster of Ustilago maydis are induced by nitrogen depletion. Fungal Biol Biotechnol. 2017;4:11.

Zambanini T, Hosseinpour Tehrani H, Geiser E, Merker D, Schleese S, Krabbe J, Buescher JM, Meurer G, Wierckx N, Blank LM. Efficient itaconic acid production from glycerol with Ustilago vetiveriae TZ1. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2017;10:131.

Zambanini T, Hosseinpour Tehrani H, Geiser E, Sonntag CK, Buesche JM, Meurer G, Wierckx N, Blank LM. Metabolic engineering of Ustilago trichophora TZ1 for improved malic acid production. Metab Eng Commun. 2017;4:12–21.

Zambanini T, Sarikaya E, Kleineberg W, Buescher JM, Meurer G, Wierckx N, Blank LM. Efficient malic acid production from glycerol with Ustilago trichophora TZ1. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2016;9:67.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Mariana Schuster and Prof. Dr. Regine Kahmann (Max Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology, Department of Organismic Interactions, Marburg) for providing the plasmid pCas9_sgRNA_0 and Dr. Kerstin Schipper and Prof. Dr. Michael Feldbrügge (Institute for Microbiology, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf) for pstorI_1rh_WT (pUMa1522). We thank Prof. Dr. Jochen Büchs (Aachener Verfahrenstechnik, RWTH-Aachen) and Dr. Lars Regestein (Biotechnikum, Hans-Knöll-Institut Jena) for advice on Bioprocess development.

Funding

This work was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture (BMEL), through the Specialist agency renewable raw materials e. V. (FNR) as part of the ERA-IB project “TTRAFFIC”. (FKZ 22030515). The laboratory of Lars M. Blank was partially funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany´s Excellence Strategy within the Cluster of Excellence 236 “TMFB” and Exzellenzcluster 2186 “The Fuel Science Center”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed significantly to the work. NW conceived and supervised the study. HHT designed and performed experiments and analyzed results with the help of NW and LMB. HHT wrote the manuscript with help of NW and LMB. IB and AL engineered the strains and SM and KAS performed fermentation experiments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors have seen and approved the manuscript. All authors have contributed significantly to the work. The manuscript has not been published and is not being considered for publication elsewhere. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. Figure S1:

Itaconate production from glycerol; Figure S2: NaOH-titrated fed-batch fermentation; Tables S1 and S2: Feeding procedures during high-density pulsed fed-batch fermentations; Table S3: Primers used in this work. Table S4: Plasmids used in this work.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hosseinpour Tehrani, H., Becker, J., Bator, I. et al. Integrated strain- and process design enable production of 220 g L−1 itaconic acid with Ustilago maydis. Biotechnol Biofuels 12, 263 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-019-1605-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-019-1605-6