Abstract

Background

Adhesions are a common postoperative surgical complication. Liquid honey has been used intraperitoneally to reduce the incidence of these adhesions. However, solid barriers are considered more effective than liquids in decreasing postoperative intra-abdominal adhesion formation; therefore, a new pectin-honey hydrogel (PHH) was produced and its effectiveness was evaluated in a rat cecal abrasion model.

Standardized cecal/peritoneal abrasion was performed through laparotomy in 48 adult Sprague-Dawley rats to induce peritoneal adhesion formation. Rats were randomly assigned to a control (C) and treatment (T) group. In group T, PHHs were placed between the injured peritoneum and cecum. Animals were euthanized on day 15 after surgery. Adhesions were evaluated macroscopically and adhesion scores were recorded and compared between the two groups. Inflammation, fibrosis, and neovascularization were histologically graded and compared between the groups.

Results

In group C, 17 of 24 (70.8%) animals developed adhesions between the cecum and peritoneum, while in group T only 5 of 24 (20.8%) did (p = 0.0012). In group C, one rat had an adhesion score of 3, sixteen had scores of 2, and seven rats had scores of 0. In group T, four rats had adhesion scores of 2, one rat had an adhesion score of 1 and nineteen have score 0 (p = 0.0003). Significantly lower grades of inflammation, fibrosis, and neovascularization were seen in group T (p = 0.006, p = 0.001, p = 0.002, respectively).

Conclusion

PHH is a novel absorbable barrier that is effective in preventing intra-abdominal adhesions in a cecal abrasion model in rats.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Postoperative intra-abdominal adhesion formation has long been considered an inevitable consequence of laparotomy, and the incidence in abdominal surgery is ranging between 67 and 93% [1–4]. Adhesion formation is a complex process involving cellular, biochemical, and immunological factors. Adhesions can develop when inflammatory responses perturb the equilibrium between fibrin formation and fibrinolysis [5]. The most common symptoms are chronic abdominal pain, small bowel obstruction, and secondary female infertility [3, 4, 6, 7]. These complications cause significant morbidity and pose a significant economic burden [6, 8].

Many potential preventive agents have been investigated, including intra-abdominal barriers, pharmacological agents, and synthetic devices [1, 4, 9]. At present, physical barriers are considered the most effective treatments for preventing postoperative intra-abdominal adhesion formation [10]. There are various types of commercially available anti-adhesion barriers such as hyaluronic acid/carboxymethyl cellulose membranesFootnote 1 and hyaluronic acid/carboxymethyl cellulose gelsFootnote 2. These membranes work by preventing contact between damaged surfaces [3, 5, 10, 11].

In recent years, honey has been used for the prevention of postoperative peritoneal adhesions [5, 12, 13]. Honey is a heterogeneous substance that inhibits the growth of both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, has anti-inflammatory effects, and promotes healing processes following peritoneal damage [5, 12, 13, 14]. Because honey has proven effective in preventing intra-abdominal adhesions in liquid form, and since anti-adhesion barriers may be more effective than intraperitoneal solutions, we developed honey-based films that could be used as physical anti-adhesion barriers.

By combining some properties of honey such as hygroscopicity, viscosity, and healing effects with the properties of a physical barrier, we hypothesized that an effective means of preventing abdominal adhesions could be developed. Mixing honey with a gelling agent (pectin) resulted in the creation of pectin-honey hydrogels (PHHs) that can be easily applied between damaged organs in the peritoneum.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the efficacy of PHHs for the prevention of intra-abdominal adhesions.

Results

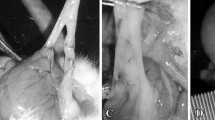

Macroscopical examination

In 48 rats, no wound site infection or presence of intra-abdominal abscess was observed.

Presence of adhesions

In group C, 17 of 24 (70.8%) animals developed adhesions between the cecum and the peritoneum, while in group T only 5 of 24 (20,8%) did (p = 0.0012) (Table 1).

In group C, 8 animals developed also adhesions between the omentum and linea alba, while in group T only 5 did. The difference in the two groups was not significant (p = 0.517).

In group C, 1 animal developed adhesion between the apex of cecum and the antimesenteric site of the distal jejunum, in group T 1 animal developed adhesion between the apex of the cecum and the side of a portion of mid-jejunum. In group T 1 animal developed adhesion between the apex of cecum and the median ligament of bladder (Table 2).

Adhesions scoring

In group C, one rat had an adhesion score of 3, sixteen had a score of 2, and seven had a score of 0. In group T, four rats had adhesion scores of 2, one rat had an adhesion score of 1 and nineteen have score 0 (p = 0,0003). Median adhesion score for group T was 2 (0,2), while for Group C was 0 (0,3). The distribution of scores in the two groups was significantly different (p = 0.0003) (Table 3).

Histopathological evaluation

The histopathological scores of the groups with respect to inflammation, fibrosis, and neovascularization are shown in Table 4. Significantly lower grades of inflammation, fibrosis, and neovascularization were seen in group T (p = 0.007, p = 0.001, p = 0.002, respectively).

Raw data are reported in an Additional file [see Additional file 1].

Discussion

The PHHs developed in this study showed a local anti-adhesive effect that prevented intra-abdominal adherence in a cecal abrasion model in rats. In the control group, 17 of 24 rats developed adhesions between the cecum and peritoneum, while in treatment group only 5 of 24 rats did. The adhesion scores and the extents of adhesions were significant reduced after treatment with PHHs without complications related to tissue healing. Histopathological scores with respect to inflammation, fibrosis, and neovascularization were significant lower in the treatment group than those in the control group.

Many experimental models exist for studying peritoneal adhesions. The cecal abrasion model is a very effective way to create peritoneal adhesions because mechanical intestinal damage activates fibrinolysis and fibrinogenesis, leading to adhesion formation. The cecal abrasion model simulates the clinical situation of the viscera being manipulated to perform surgery. We modified this model by standardizing the number of passages with the gauze on the cecum and by assign animals to C or T group only after having performed the scraping. The first modification was made in order to standardize the damage inflicted to the cecal serosal. The second has been done in order to avoid a possible bias given by knowing in advance the group allocation of the specimen, thus influencing the surgeon toward performing less or more severe lesions.

Several researchers have used different scoring systems for grading adhesions [3, 12, 15, 16]. Many of these studies used Swolin’s scoring model, which macroscopically grades adhesions from 0 to 3 according to their severity. We chose to use this method because it is easy to apply and allowed us to express the results clearly [17].

In terms of methods of preventing adhesions, many studies have reported that pharmacological agents are not effective [10, 11]. Physical barriers are the most widely used method of adhesion prevention in humans, and have been shown to be effective in preventing intra-abdominal adhesions in animal models [10]. During recent years, many commercially available substances have been used to reduce the occurrence of postoperative adhesions. Carboxymethylcellulose bioresorbable membrane is one such material. Some studies have demonstrated that a carboxymethylcellulose-based membrane1 significantly reduces the incidence and extent of adhesions. However, the therapeutic effect of this membrane may be limited to the site of application, and the material seems difficult to handle in clinical practice [3, 5, 18].

In response to the need for effective solutions, honey has become increasingly popular and several studies have been published demonstrating its effectiveness in assisting the peritoneal healing process [5, 12]. However, studies regarding its effects on preventing peritoneal adhesions are still limited. Aysan and Emre used honey intraperitoneally to reduce postoperative adhesion formation, and reported that the treatment was effective and was associated with no toxic effects [5, 12].

In a preliminary unpublished in vivo test of the pectin-honey hydrogels, we treated three animals with PHH produced with 4 g of honey. All the animals died from ascites caused by the osmotic effect of the PHH. This fact was not reported by Aysan and Emre, and could have been caused by the presence of pectin in the films, the low content of water in the PHH, or the hygroscopicity of honey. In the second part of the study, we used 2 g of honey for PHH construction and none of the animals showed any side effects. This composition of PHH reduced inflammation and prevented adhesions formations without causing any side effects [19]. The results of this study demonstrated that PHH is effective in preventing the formation of postoperative adhesions. The material can be easily applied by surgeons and can be placed in deep anatomical sites. The PHHs are biocompatible and rapidly metabolized in contrast with the carboxymethylcellulose-polylactic acid membranes [18]. We hypothesize that the mechanical barrier combined with the absorption properties of honey may have played a key role in the inhibition of adhesion formation in the present study. More studies are needed on this topic, but the intraperitoneal use of PHHs does seem to significantly reduce the occurrence of postoperative adhesions at the site of application. PHH are not effective in preventing adhesion at distant sites from application, as demonstrated by the presence of adhesions between other organs other than cecum and peritoneum in treated animals. This is a limit of antiadhesion barriers, that extends to the product we tried in this study.

The present study was limited in one key way. We only used one model of adhesion formation, so we cannot be sure if the PHHs would behave the same if tested in a range of different models or even in genuine cases. Further, using dry gauzes to create the cecal abrasion, could be a confounding factor, because adhesions could be generated by small pieces of gauze lost during the procedures and acting as a foreign body on the surface of the intestine.

Another important limit is given by the use of a rat model. In fact, many agents that proved effective in rats couldn’t be demonstrated as effective in humans, and basing from this study we cannot predict PHH behaving differently.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we observed that damaged cecal and abdominal wall surfaces treated with PHHs are significantly less likely to develop postoperative lesions. However, further investigations are needed in order to establish whether these results are transferable to other models and genuine cases, and to establish the true relevance of this treatment modality to the prevention of postoperative adhesions in the peritoneum.

Methods

Preparation of PHHs

We used a modified version of the preparation method described by Walker [19, 20]. Briefly, the PHHs were prepared from a starting solution (1:1 v/v) of liquid honeyFootnote 3 and sterile deionized water. Half this volume of pectin powderFootnote 4 was then added gradually and with continuous stirring until the mixture was homogenized to obtain a final mixture of 1:1:1 v/v of honey, water and pectin. The resulting foam was spread into 2-mm films and hot-air-dried at 40 ± 0.5 °C for 6 h. We then cut the hard substance into 3 × 3-cm squares and further conditioned it in an air drier at 25 ± 1 °C for 5 d. The films were then collected and vacuum packed in polyethylene. All membranes were sterilized by gamma-irradiation at 25 kgray by Sterigenics International (Sterigenics International LLTC, Bologna, Italy) [19].

Surgical procedures

All procedures were approved by the Bioethical Committee of the University of Turin and by the Italian Ministry of Health (protocol number 262/2015-PR on 20/04/2015).

A total of 48 adult male Sprague-Dawley rats weighting 225–250 g were purchased from Charles RiversFootnote 5 (Italy). All rats were housed in single cages for 7 d prior to the start of the experiment. The room temperature was set at 23 °C for the experimental period and the cages were cleaned daily. The rats were fed a commercial diet and water was provided ad libitum.

Anesthesia was induced by intramuscular administration of 5 mg/kg of xylazineFootnote 6 and 50 mg/kg of tiletamine and zolazepamFootnote 7. The rats we kept under anesthesia for 1 h, during which the abdomen was shaved and the skin was swabbed three times using an iodopovidone-chlorhexidine scrub.

A 4-cm midline incision was made in the abdominal wall. The cecum was exposed, and the apex was abraded with surgical gauze 100 times [21]. The left abdominal wall was abraded with a No. 21 scalpel blade 100 times. The cecum was returned to the abdominal cavity in its proper anatomic position. The scratching procedure was performed until hemorrhagic points were observed on the surface without perforation.

All surgeries were performed by the same operator (MG). Only after inducing injuries, the rats were randomly assigned to the treatment or control groups. In the treatment group, the PHHs were applied between the injured cecum and peritoneum. The midline incision was closed in two layers; the fascia was closed with 3-0-USP glycomer 631Footnote 8, while the skin was closed with 3-0-USP nylon8. All surgical procedures took approximately 20 min. During the procedure and shortly thereafter, the rats were placed on a warm plate to avoid hypothermia, and 5-mL isotonic sodium chloride (0.9%) was administered subcutaneously. Animals were randomly divided into two groups of 24 animals each, using a free online calculator (www.random.org):

-

Group C: negative control group. No treatment applied.

-

Group T: group treated by applying the PHHs over the injury.

Macroscopical examination

After 15 d, euthanasia was performed and the abdominal cavity was inspected through a U-shaped incision in the anterior abdominal wall. Signs of wound site infection or anastomotic abscesses were recorded.

Presence of adhesions

Any macroscopic adhesion in the abdominal cavity, either involving the abrasion site or other organs were identified and recorded. Number of adhesions per group indicated as percentage were compared with a Fisher exact test.

Adhesions scoring

Adhesions were scored according to the protocol described by Swolin [17] (Table 5). Scores were then compared between groups with a Mann-Whitney test.

Histopathological evaluation

The cecum and abdominal wall were harvested for histopathological examination and the tissue samples fixed in a 10% formaldehyde solution for histopathological examination. Samples were routinely processed by dehydration and paraffin embedding, and 5-μm cross-sections were produced. The samples were examined under a light microscope after hematoxylin-eosin staining and evaluated blindly by two expert pathologists to determine the presence of inflammation, fibroblastic activity, and neovascularization according to scores in accordance with Swolin [17] (Table 6).

Statistical analysis

Sample size was calculated for the parameter “Presence of adhesions” hypothesizing for group 1 75% and for group 2 25% of animals with adhesions. Alpha level was set at 0.050 and Power at 89%. Further 4 animals were added to the result to account for possible deaths in the operative or postoperative period. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 6 softwareFootnote 9. The normality of the data was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk normality test. Non parametric tests were used for not-normally distributed data. A p < value 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Notes

Sanofi S.p.A, Milano, Italy

Hanmi Medicare, Songpa-gu, Seoul, South Korea

DermaSciences, Princeton, NY

ARDET s.r.l., Cuneo, Italy

Charles Rivers, Lecco, Italy

Bayer Animal Health, Milano, Italy

Virbac, Milano, Italy

Covidien, Segrate Milano, Italy

GraphPad Software Inc, La Jolla, USA

Abbreviations

- PHH:

-

Pectin-honey hydrogel

References

Yildiz T, Ilce Z, Yildirim M, Akdogan M, Yurumez Y, Varlikli O, Dilek FH. Antienflamatuar and antiadhesive effect of clioquinol. Int J Surg. 2015;15:17–22.

Cassidy MR, Sheldon HK, Gainsbury ML, Gillespie E, Kosaka H, Heydrick S, Stucchi AF. The neurokinin 1 receptor regulates peritoneal fibrinolytic activity and postoperative adhesion formation. J Surg Res. 2014;191:12–8.

Chaturvedi AA, Lomme RMLM, Hendriks T, van Goor H. Prevention of postsurgical adhesions using an ultrapure alginate-based gel. Br J Surg. 2013;100:904–10.

Parsaei P, Karimi M, Asadi SY, Rafieian-kopaei M. Bioactive components and preventive effect of green tea (Camellia sinensis) extract on post-laparotomy intra-abdominal adhesion in rats. Intern J Surg. 2013;11:811–5.

Emre A, Akin M, Isikgonul I, Yuksel O, Anadol AZ, Cifter C. Comparison of intraperitoneal honey and sodium hyaluronate-carboxymethylcellulose (Seprafilm™) for the prevention of postoperative intra-abdominal adhesions. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2009;64:363–8.

Poehnert D, Abbas M, Kreipe HH, Klempnauer J, Winny M. High reproducibility of adhesion formation in rat with moso-stitch approximation of injury cecum and abdominal wall. Int J Med Sci. 2015;12:1–6.

Yan S, Yue Y, Zeng L, Yue J, Li W, Mao C, Yang L. Effect of intra-abdominal administration of ligustrazine nanoparticles nano spray on postoperative peritoneal adhesion in rat model. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41:1942–50.

Lim R, Stucchi AF, Morrill JM, Reed KL, Lynch R, Becker JM. The efficacy of a hyaluronate-carboxymethylcellulose bioresorbable membrane that reduces postoperative adhesions is increased by the intra-operative co-administration of a neurokinin 1 receptor antagonist in a rat model. Surg. 2010;148:991–9.

Whang SH, Astudillo JA, Sporn E, Bachman SL, Miedema BW, Davis W, Thaler K. In search of the best peritoneal adhesion model: comparison of different techniques in a rat model. J Surg Res. 2011;167:245–50.

Hwang HJ, An MS, Ha TK, Kim KH, Kim TH, Choi CS, Hong KH, Jung SJ, Kim SH, Rho KH, Bae KB. All the commercially available adhesion barriers have the same effect on adhesion prophylaxis? A comparison of barrier agents using a newly developed, severe intra-abdominal adhesion model. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:1117–25.

Lim R, Morrill JM, Lynch RC, Reed KL, Gower AC, Leeman SE, Stucchi AF, Becker JM. Pratical limitations of bioresorbable membranes in the prevention of intra-abdominal adhesions. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:35–42.

Aysan E, Ayar E, Aren A, Cifter C. The role of intra-peritoneal honey administration in preventing post-operative peritoneal adhesions. Eur J Obst Gyn Repr Biol. 2002;104:152–5.

Cooke J, Dryden M, Patton T, Brennan J, Barrett J. The antimicrobial activity of prototype modified honeys that generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) hydrogen peroxide. BMC Vet Res. 2015;8:20–5.

Carnwath R, Graham EM, Reynolds K, Pollock PJ. The antimicrobial activity of honey against common equine wound bacterial isolates. The Vet J. 2014;199:110–4.

Bae SH, Son SR, Sakar SK, Nguyen TH, Kim SW, Min YK, Lee BT. Evaluation of the potential anti-adhesion effect of the PVA/Gelatin membrane. J Biomed Mat Res App Biom. 2014;102B:840–9.

Caglayan K, Gungor B, Cinar H, Erdogan NY, Koca B. Preventing intraperitoneal adhesions with linezolid and hyaluronic acid/carboxymethylcellulose: a comparative study in cecal abrasion model. Am J Surg. 2014;208:106–11.

Swolin K. Experimented studien zur prophylaxe von intraabdominalen verwachsungen: Versuche an der Ratte mit einer Emulsion aus Lipid und Prednisolon. Acta Ob Gin Scandiv. 1966;45:473–98.

Ersoy E, Ozturk V, Yazgan A, Ozdogan M, Gundogdu H. Comparison of the two types of bioresorbable barriers to prevent intra-abdominal adhesions in rats. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:282–6.

Giusto G, Beretta G, Vercelli C, Valle E, Iussich S, Borghi R, Odetti P, Monacelli F, Tramuta C, Grego E, Nebbia P, Robino P, Odore R, Gandini M. A simple method to produce pectin-honey hydrogels and its characterization as new biomaterial for surgical use. J Biomed Mat Res: part B, Under review.

Walker JE. Method of preparing homogeneous honey pectin composition. Patented. 1942. https://worldwide.espacenet.com/publicationDetails/biblio?CC=US&NR=2295274A&KC=A&FT=D.

Singer ER, Livesey MA, Barker IK, Hurtig MB, Conlon PD. Development of a laboratory animal model of postoperative small intestinal adhesion formation in the rabbit. Can J Vet Res. 1996;60:296–304.

Acknowledgements

Sterigenics International LLC (Minerbio, Bologna, Italy).

Funding

The study was financed with the grant PRIN 2012.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301636926_Dataset_ntraperitoIneal_adhesions_in_rats) and its additional files.

Authors’ contributions

GG and MG designed and performed the study, acquired, analyzed and interpreted the data, wrote and reviewed the paper. CV and AA performed the study, acquired and analyzed the data, wrote and reviewed the paper. SI performed the histological analysis, interpreted the data and reviewed the paper. EM and RO analyzed, interpreted the data and reviewed the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

All procedures were approved by the Bioethical Committee of the University of Turin and by the Italian Ministry of Health (protocol number 262/2015-PR on 20/04/2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Raw data of adhesions necropsy and histological scoring. (PDF 99 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Giusto, G., Vercelli, C., Iussich, S. et al. A pectin-honey hydrogel prevents postoperative intraperitoneal adhesions in a rat model. BMC Vet Res 13, 55 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-017-0965-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-017-0965-z