Abstract

Background

Targeted chronic disease programs are vital to improving health outcomes for Indigenous people globally. In Australia it is not known where evaluated chronic disease programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have been implemented. This scoping review geographically examines where evaluated chronic disease programs for Aboriginal people have been implemented in the Australian primary health care setting. Secondary objectives include scoping programs for evidence of partnerships with Aboriginal organisations, and use of ethical protocols. By doing so, geographical gaps in the literature and variations in ethical approaches to conducting program evaluations are highlighted.

Methods

The objectives, inclusion criteria and methods for this scoping review were specified in advance and documented in a published protocol. This scoping review was undertaken in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) scoping review methodology. The search included 11 academic databases, clinical trial registries, and the grey literature.

Results

The search resulted in 6894 citations, with 241 retrieved from the grey literature and targeted organisation websites. Title, abstract, and full-text screening was conducted by two independent reviewers, with 314 citations undergoing full review. Of these, 74 citations evaluating 50 programs met the inclusion criteria. Of the programs included in the geographical analysis (n = 40), 32.1% were implemented in Major Cities and 29.6% in Very Remote areas of Australia. A smaller proportion of programs were delivered in Inner Regional (12.3%), Outer Regional (18.5%) and Remote areas (7.4%) of Australia. Overall, 90% (n = 45) of the included programs collaborated with an Aboriginal organisation in the implementation and/or evaluation of the program. Variation in the use of ethical guidelines and protocols in the evaluation process was evident.

Conclusions

A greater focus on the evaluation of chronic disease programs for Aboriginal people residing in Inner and Outer Regional areas, and Remote areas of Australia is required. Across all geographical areas further efforts should be made to conduct evaluations in partnership with Aboriginal communities residing in the geographical region of program implementation. The need for more scientifically and ethically rigorous approaches to Aboriginal health program evaluations is evident.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

It is well established that Indigenous people experience poorer health outcomes than non-Indigenous people globally [1]. Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, like other Indigenous populations in Canada, New Zealand and the United States, endure ongoing health inequities such as a high burden of chronic disease and difficulty accessing culturally safe health care [2, 3]. Chronic diseases with strong environmental and behavioural etiology, such as cardiovascular disease and Type Two Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM), contribute to approximately 80% of the mortality gap between Australian Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people between 35 and 74 years of age [4]. Aboriginal people residing in more geographically remote areas experience further disadvantage and a higher burden of chronic disease [5]. For example, the proportion of Aboriginal people with Diabetes Mellitus in Very Remote areas of Australia is approximately twice that of Aboriginal people in Major Cities [6]. The lack of affordable fresh fruit and vegetables in these areas is one contributing factor [7].

Targeted chronic disease prevention and management programs delivered in the primary health care setting are imperative to alleviating the burden of disease and improving health outcomes for Indigenous people [3, 8]. In Australia, little progress has been made in improving health outcomes, the distribution of chronic disease, and risk factors for developing disease for Aboriginal people [2, 9]. This is despite numerous funded Aboriginal chronic disease programs implemented at a national level (e.g., Aboriginal Chronic Disease Package, 2008) and initiatives under the ‘Closing the Gap’ policy [2, 9]. The ineffectiveness of health programs has been attributed to multiple factors, including short government funding cycles, a lack of community ownership and consultation, and a ‘one size fits all’ approach to program design and implementation [10, 11]. Furthermore, only a small proportion of Aboriginal health programs have been evaluated (8%), with only 6% of program evaluations applying rigorous evaluation methodologies to measure program effectiveness [12, 13]. The paucity of Aboriginal health program evaluations has resulted in little opportunity to improve or modify existing programs in response to program outcomes, contributing to the cycle of program ineffectiveness.

The need for Aboriginal community-driven programs and governance of primary health care services, as supported by the international right to self-determination for Indigenous people, is becoming increasingly recognised as a key strategy to alleviating the burden of chronic disease [14,15,16]. Strong evidence supports the role of Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs) and other Aboriginal organisations in improving the accessibility, appropriateness and effectiveness of primary health care services through the provision of culturally appropriate care which respects the cultural values and beliefs of Aboriginal people [8]. Therefore, the involvement of ACCHOs and other Aboriginal organisations in the design and implementation of chronic disease programs is imperative [15, 17,18,19]. Moreover, a community-based approach to program design, implementation, evaluation, sustainability and transferability acknowledges the diversity of Aboriginal culture, language and customs [10]. This ensures that chronic disease programs are tailored to local needs and evaluated in partnership with community, recognises the strengths and resilience of Aboriginal people, and empowers Aboriginal communities to promote their own health and wellbeing [20].

Although there has been a rhetorical shift from government initiated health programs to community-developed health programs for Aboriginal people in Australia [21], it is not known whether the distribution of chronic disease programs has been proportionate to the population distribution of Aboriginal people, or to the burden of chronic disease. Furthermore, it is not known geographically where evaluated chronic disease programs for Aboriginal people in the primary health care setting have been implemented. Therefore, the purpose of this scoping review was to identify where evaluated chronic disease programs have been implemented in the primary health care setting [22]. Specifically, this review sought to determine whether this distribution was proportionate to the Aboriginal population distribution, and burden of disease across all geographical areas of Australia and by doing so, highlight geographical gaps in the literature to identify priority areas for the implementation of chronic disease programs. Secondary objectives included scoping for evidence of partnerships with ACCHOs and other Aboriginal organisations, in addition to the use of ethical guidelines or protocols in the reporting of programs.

Methods

This study provides a systematic scoping review geographically examining the distribution of evaluated chronic disease prevention and management programs implemented for Australian Aboriginal people in the primary health care setting which includes community-health settings, general practice clinics and ACCHOs [22]. This review was undertaken in accordance with the methodology for conducting scoping reviews as outlined in the Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2017: Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews [23]. Search terms were designed in a PCC (Population, Concept, Context) format by the research team and in collaboration with a health librarian. The premise and methods for this review have been published elsewhere in greater detail [22]. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were adhered to in the reporting of this review (Additional file 1).

Search strategy

A preliminary search was conducted in MEDLINE and CINAHL using keywords to develop a tailored search strategy for each information source. A combination of Boolean operators, truncations and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were used to develop database search strategies (Additional file 2). The following databases were searched: Ovid MEDLINE, CINAHL (EBSCOhost), Scopus, Embase (Elsevier), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, ISI Web of Science, SocINDEX (EBSCO-host), Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest), PubMed Central and PsycINFO (OVID).

Keywords were used to search the following information sources for unpublished studies, grey literature, and trials in order to avoid publication bias: Lowitja Institute, Indigenous Healthinfonet, National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO), Department of Health (Australian Government), informIT, Google, Cochrane Central Trials Register of Controlled Trials, ANZ Clinical Trials Registry, ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO International Clinical trial Registry Platform (ICTRP), Primary Health Care Research and Information Service (PHCRIS), ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global, Trove and OAIster.

Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria

This review considered literature based on the following criteria (Table 1).

No restrictions were placed on the quality of evaluation or study design. As stated in the scoping review protocol, programs evaluated by any party to any level were included [22]. Literature published from 1 January 2006, was included in order to capture programs published since the launch of the ‘Closing the Gap’ campaign, which resulted in a greater focus on addressing health inequities experienced by Aboriginal people in Australia [9].

For consistency, the term ‘Aboriginal’ has been used throughout this review to refer to both Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people in Australia. This is due to brevity, and no disrespect is intended to any individual or group. The term ‘Indigenous’ has been reserved for the global context.

Study selection and data extraction

Searches for published and unpublished literature were conducted by a health librarian. Titles and abstracts retrieved from the search were screened independently by two reviewers (HB and MJB). Conflicts were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (CK). Full text review and data extraction was then conducted independently by two reviewers (HB and MJB) on selected articles. Reasons for exclusion were provided for articles that did not meet the review criteria. The reference lists of citations requiring full text review were also screened for additional citations in order to ensure that all possible literature was included.

Extracted data were categorised under the following headings: author, year of publication, year of program implementation, location of program implementation/evaluation, evaluation methods, involvement of an ACCHO/other Aboriginal organisation and reference to Australian National Health and Medical Research Council’s (NHMRC) ‘Values and Ethics: Guidelines for Ethical Conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research’ guideline, and other ethical protocols [24, 25]. Geographical coordinates were then assigned to included programs based on the extracted data. Where specific implementation sites were not stated, the approximate location(s) were geocoded and coordinates extracted. If this information was unavailable, the corresponding author was contacted. If studies did not specify where the program was evaluated, the institution listed for the first author was used as a proxy for place of evaluation. This assumed that first authorship implied a lead role in the evaluation.

Coordinates were then exported to ArcGIS® ArcMap™ and overlayed with the Remoteness Areas of Australia for analysis [26]. To define remoteness, the Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) was applied, which is a categorisation of the Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA+) [27]. Areas are classified as: i) Major Cities of Australia, ii) Inner Regional Australia, iii) Outer Regional Australia, iv) Remote Australia, and v) Very Remote Australia. Euclidean distance between the implementation site and evaluation were also extracted in ArcGIS® ArcMap™ [26]. Summary statistics were produced to examine the distance between implementation site(s) and place of evaluation. Locations of implementation and evaluation were stratified by Remoteness Area and cross-tabulated.

The extracted data, synthesis of findings and review outcomes, were critically reviewed for culturally appropriateness by two Aboriginal researchers, as stated in the review protocol [22].

Results

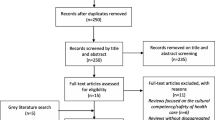

Database searches yielded 14,366 citations. An additional 241 citations were retrieved from a search of the grey literature and targeted organisation websites. A total of 6894 title and abstracts were screened, with duplicates removed. The full texts of 314 citations were screened for relevance to the review criteria, identifying 74 pertinent records evaluating 50 chronic disease prevention and management programs (Fig. 1 – PRISMA Flow Diagram). One of these records included reference to three evaluated programs [28].

Reasons for excluding records were provided (Additional file 3). The most frequent reason provided for exclusion was that the record was ‘not a program evaluation’ (n = 52), followed by ‘Sub-studies met inclusion criteria but already included in search, or sub-studies did not meet inclusion criteria’ (n = 50) and ‘not a primary health care delivered program’ (n = 30). Excluded records included 20 records which focused on evaluating national screening and vaccination programs. These were excluded as findings were based on national or state-wide aggregate data which would have been difficult to include in the geographical analysis.

Finding 1: heterogeneity of included programs

Citations meeting the review criteria (n = 74) included evaluated programs (n = 50) that addressed multiple chronic diseases (n = 16), a specific chronic disease (cardiovascular disease n = 5, diabetes mellitus n = 6, chronic kidney disease n = 3, liver disease n = 2, mental illness n = 4, oral disease n = 2 and polycystic ovarian syndrome n = 1) or risk factors for developing chronic disease (drug and alcohol misuse n = 2, poor nutrition and physical inactivity n = 3 and smoking n = 6) (Table 2). Of the included programs, 74% (n = 37) aimed to prevent and/or manage chronic disease using disease-specific screening, early intervention or treatment strategies, with the remaining programs (n = 13) applying general health promotion approaches to disease prevention, such as empowering participants to implement activities to improve their health.

The data collection methods of program evaluations varied, with over half of the program evaluations using a mixed methods approach (n = 26, 52%), followed by a quantitative only (n = 19, 38%) or qualitative only (n = 4, 8%) approach. The methods of evaluation were not reported for one program [28], however, a summary of outcomes were provided; hence the program was included in the review. Of the included programs, only seven were evaluated using a randomised controlled trial (RCT) study design, with only one study (an RCT) including an economic evaluation of program cost-effectiveness.

Finding 2: geographical distribution of programs

Four of the included programs were excluded from the geographical analysis as programs were implemented state-wide or nationally (Home Medicines Review Program [94, 95], Get Healthy Service Program [75], QAAMS Program [77,78,79] and COACH Program [82]). Five of the included programs were also excluded from the geographical analysis as authors did not respond to the request for additional information. Geographical coordinates for program implementation sites were available for 41 of the included programs (82% of all included programs). However, one program was omitted from the analyses as the evaluation was undertaken outside of Australia as part of a multi-site program evaluation [47]. A total of 81 implementation sites for the 40 programs (80% of all included programs) with available locations were geo-coded and geographically analysed (Table 3).

Of the included programs in the geographical analysis (n = 40), 32.1% were implemented for Aboriginal people residing in Major Cities of Australia and 29.6% for Aboriginal people residing in Very Remote Australia. The remaining programs were implemented for Aboriginal people residing in the intermediate remoteness areas of Inner Regional Australia, Outer Regional Australia, and Remote Australia (12.3, 18.5 and 7.4% respectively).

The location of program evaluation was reported for 25 of the programs included in the geographical analysis. First author affiliation was used as a proxy for the location of program evaluation for the remaining 15 programs. Evaluation activity was predominately undertaken in Major Cities of Australia (71.6%), with the remaining studies declining in order of remoteness. Of the identifiable implementation locations (n = 81), 18 (22%) of these also had an evaluation undertaken on site. For studies with the site(s) of implementation and evaluation available, the mean distance between implementation and evaluation was 660 km (95% CI 470–850; maximum 3041; median 223). A visual representation of the distribution of included programs is provided (Fig. 2).

Locations of the implementation and evaluation of programs in relation to the Remoteness Areas of Australia [27]

The sample size of programs retrieved for highly prevalent chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease and T2DM, was deemed insufficient to geographically analyse whether the distribution of evaluated programs were proportionate to the burden of chronic disease across all Remoteness areas.

Finding 3: ethical approaches to program evaluation

Of the 50 programs included in the review, 39 (78%) reported on the involvement of an ACCHO in the implementation or evaluation process (Additional file 4). Of the included programs that did not report on the involvement of an ACCHO, six of these referred to the involvement of another Aboriginal organisation (12%). Overall, 90% (n = 45) of the included programs collaborated with an Aboriginal organisation in the implementation and/or evaluation of the program.

When examining the affiliation of the first author of the included citations (n = 74), 74% (n = 55) were associated with a university or research institution, 9.5% (n = 7) with an ACCHO or other Aboriginal organisation, 9.5% (n = 7) with a non-Aboriginal health service or Non-Government Organisation (NGO) and 7% (n = 5) with both a university or research institution and an ACCHO.

Of the 74 citations retrieved, seven explicitly referred to the NHMRC’s ‘Values and Ethics: Guidelines for Ethical Conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research’ as a guideline underpinning the evaluation design and conduct [24]. However, 70% of citations (n = 52), particularly those published in a peer-reviewed journal, included a formal statement of ethical review and approval by a Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) affiliated with a research institution or university. Only 23 citations (31%) discussed the use of other ethical protocols or a community-based ethical review process. These citations varied broadly in their descriptions of adhering to local cultural guidelines or consulting with an appointed Aboriginal advisory group. For example, Askew et al. (2016) [32] described the formation of a research advisory group consisting of both Aboriginal community members and experienced researchers who provided research governance and oversight, whereas Treloar et al. (2018) [98] described consulting with an Aboriginal advisory group in the program development phase rather than the evaluation process. Consideration of cultural sensitivities was also discussed broadly in some papers, including processes undertaken to build rapport with collaborating Aboriginal communities prior to the conduct of an evaluation [59, 72] and the receipt of cultural guidance or support from a steering group of Aboriginal people or Elders [40, 83].

Discussion

This review highlights the paucity of Aboriginal chronic disease program evaluations conducted in the primary health care setting across all geographical regions of Australia. Previous studies have acknowledged that only a small proportion of Aboriginal health programs have been subject to an evaluation process [12, 13]. Therefore, the included programs in this review are not representative of all chronic disease programs implemented for Aboriginal people across Australia. Of those included, the majority targeted highly prevalent chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease and T2DM, or risk factors for developing chronic disease, such as smoking and physical inactivity [2]. Due to the heterogeneity of programs across all geographical regions and small sample size, the review was unable to ascertain whether the spread of programs was proportionate to the distribution of chronic disease across all Remoteness Areas of Australia. For example, it was difficult to conclude whether a greater focus on the management of T2DM for Aboriginal people residing in Very Remote areas is required, where the prevalence of T2DM is approximately twice of Aboriginal people residing in Major Cities [6]. However, the small proportion of evaluated social and emotional wellbeing (SEWB) programs (e.g., mental health programs) was noted across all geographical regions, supporting the need for tailored early intervention and screening SEWB programs for Aboriginal people [19]. Internationally, tailored programs for mental health prevention have been deemed particularly important for Indigenous people, particularly those including an exploration of cultural identity [102, 103].

Overall, Major Cities and Very Remote areas of Australia displayed similar levels of chronic disease program implementation activity, with less activity noted for Inner and Outer Regional (IOR) areas and Remote areas of Australia. A greater focus on chronic disease programs for Very Remote Aboriginal people when compared to IOR or Remote Aboriginal people could be informed by national data which indicates that the burden of chronic disease in Aboriginal people increases with Remoteness [6]. However, less Aboriginal people reside in Very Remote areas when compared to IOR areas (11.9% compared to 23.7 and 20.3% respectively), suggesting there is a need for the evaluation of chronic disease programs for Aboriginal people residing in IOR areas [101]. Across all geographical areas in Australia, it is anticipated that the demand for chronic disease prevention programs will increase over time, due to a higher Aboriginal population growth rate when compared to non-Aboriginal populations as indicated by 2017 national data (2.26 babies per Aboriginal woman compared to 1.75 babies per non-Aboriginal woman) [104, 105]. The demand for chronic disease programs may also increase for Indigenous people in other countries (e.g., Canada) experiencing similar population growth (2.2 babies per Aboriginal woman compared to 1.6 babies per non-Aboriginal woman in Canada) [106].

When considering evaluation activity, higher levels of evaluation were noted for Major Cities (71.6%) when compared to Very Remote areas (1.2%). This is despite the fact that national data indicates that less Aboriginal people reside in Major Cities compared to the total Australian population (37% compared to 73% respectively) [101]. Further to this, the proportion of Aboriginal people is higher in all other Remoteness Areas of Australia, relative to the total Australian population [101]. This finding suggests there is a need for more Aboriginal community-led research as supported by the broader literature [15, 19, 20]. However, caution should be applied in interpreting these findings as first author affiliation was used as a proxy for the location of program evaluation for 15 of the 40 programs included in the geographical analysis. The rationale for this assumption was that first authorship implied a lead role in the evaluation.

When examining first author affiliation for all included citations (n = 74), 74% (n = 55) of citations were associated with a university or research institution, with only 9.5% (n = 7) citations associated with an ACCHO or other Aboriginal organisation. A previous review of Aboriginal health programs in Australia also found that the majority of program evaluations (72%) were led by a research institution or university rather than an Aboriginal community organisation [107]. However, first author affiliation with a research institution or university does not necessarily mean that the evaluation did not have significant Aboriginal community input; particularly as 90% (n = 45) of included programs provided details of collaborating with an ACCHO or other Aboriginal organisation in the development or evaluation of the program. Strong support for the appropriateness of ACCHOs as a collaborating organisation for activities involving Aboriginal people is found in the literature [108]. Generally, ACCHOs are geographically accessible to Aboriginal people and valued for the provision of culturally safe primary health care [8, 109, 110].

Although the majority of programs partnered with an ACCHO or Aboriginal organisation, it is difficult to ascertain for all programs, the degree of community ownership and involvement in the evaluation process. This includes steps taken by evaluators to ensure the evaluation process was ethically and culturally appropriate for Aboriginal people [20]. As reporting the formal ethical review of a research project is a standard requirement for publication in a peer-reviewed journal, both nationally and internationally, it is not surprising that the majority of citations (70%, n = 52) provided a statement of formal review by an appointed committee (e.g. HREC). However, only 31% of the included citations (n = 23) provided some evidence of actions taken to adhere to Aboriginal community-based ethical protocols, or engagement with an Aboriginal advisory group in the design of the program or conduct of the evaluation. Indeed, a statement of formal ethical review does not provide sufficient detail describing how Aboriginal people were consulted and included in the evaluation process. Other Aboriginal program evaluation frameworks and models of Aboriginal health research should also be consulted, which are valuable in informing approaches to conducting program evaluations in partnership with Aboriginal people [20, 25, 111, 112]. Program evaluations of Aboriginal programs excluding partnerships, often lack relevance and integrity, and fail to translate to outcomes for Aboriginal people [12, 113].

Limitations

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of this review. The selection criteria of the review influenced the geographical spread of studies retrieved. National screening and vaccination programs were excluded as program evaluations used national aggregate data. Geographical findings may also have been impacted by the exclusion of other programs which met the review criteria, but were excluded from the geographical analysis due to state-wide or national program implementation (Home Medicines Review Program [94, 95], Get Healthy Service Program [75], QAAMS Program [77,78,79] and COACH Program [82]). Furthermore, authors of five programs did not respond with additional information regarding the geographical program implementation locations which may also have influenced the analysis.

It is not known what proportion of evaluated chronic disease programs or implemented chronic disease programs have been included; a limitation cited by a similar review [107]. It is also possible that evaluated programs targeting more distal risk factors for chronic disease may have been overlooked. The availability of evaluation reports may also have influenced the types of citations retrieved. A recent investigation into the evaluation of health programs implemented for Aboriginal people in Australia found that only 33% of evaluation reports were available [20]. Further to this, it is acknowledged that a substantial amount of literature pertaining to Australian Aboriginal people is published in the grey literature [114]. Although the authors have made every effort to conduct a thorough search of the grey literature, it is possible some evaluation reports may not have been captured in this scoping review.

Recommendations

A greater focus is required on evaluating chronic disease prevention and management programs for Aboriginal people across all geographical areas, particularly for Aboriginal people residing in Inner and Outer Regional areas of Australia. In addition, there is a need to focus on evaluating Social and Emotional Wellbeing (SEWB) programs developed for Aboriginal people. Programs should be implemented and evaluated in collaboration with partnering ACCHOs or other Aboriginal organisations, with an emphasis on accountability, sustainability, capacity-building, ownership and Aboriginal strengths. This includes equipping Aboriginal organizations with skills in conducting program evaluations. Evaluation reporting should be transparent in describing ethical approaches to conducting the program evaluation in partnership with Aboriginal communities. Furthermore, an evaluation process should be integrated into the design of Aboriginal health programs. Evaluation outcomes should be publicly available, ideally through the peer-reviewed literature, in order to build the evidence around the effectiveness of chronic disease programs for Indigenous peoples globally.

Conclusions

A greater focus on the implementation and evaluation of chronic disease prevention and management programs for Aboriginal people in Australia is required, particularly for Aboriginal people residing in Inner and Outer Regional Areas of Australia. There is also a need to conduct evaluations of Social and Emotional Wellbeing (SEWB) programs across all geographical regions. This review highlights the need for more ethically rigorous approaches to Aboriginal health program evaluations which engage Aboriginal people in all stages of program design, implementation, evaluation and sustainability.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ACCHO:

-

Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Organisation

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- HbA1C:

-

Glycated Haemoglobin

- HREC:

-

Human Research Ethics Committee

- IOR:

-

Inner and Outer Regional

- NGO:

-

Non-Government Organisation

- NHMRC:

-

National Health and Medical Research Council

- QAAMS:

-

Quality Assurance for Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Medical Services

- RCTs:

-

Randomised Controlled Trials

- SEWB:

-

Social and Emotional Wellbeing

- T2DM:

-

Type Two Diabetes Mellitus

References

Anderson I, Robson B, Connolly M, Al-Yaman F, Bjertness E, King A, et al. Indigenous and tribal peoples' health (the lancet–Lowitja Institute global collaboration): a population study. Lancet. 2016;388(10040):131–57.

Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council (AHMAC). Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander health performance framework 2017 report. Canberra: AHMAC; 2017.

Pulver L, Ring I, Waldon W, Whetung V, Kinnon D, et al. Indigenous health – Australia, Canada, Aotearoa New Zealand and the United States - laying claim to a future that embraces health for us all. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2010. https://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/financing/healthreport/IHNo33.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2019

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Contribution of chronic disease to the gap in adult mortality between aboriginal and Torres Strait islander and other Australians. Canberra: AIHW; 2011. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/79b73a27-c970-47f0-931b-32d7badade40/12304.pdf.aspx?inline=true. Accessed 15 Jan 2019

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Australian burden of disease study 2011: impact and causes of illness and death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2011. Canberra: AIHW; 2016. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/e31976fc-adcc-4612-bd08-e54fd2f3303c/19667-bod7-atsi-2011.pdf.aspx?inline=true. Accessed 17 Jan 2019

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). 4727.0.55.006 - Australian aboriginal and Torres Strait islander health survey: updated results, 2012–13. Canberra: ABS; 2014. http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/4727.0.55.0062012%E2%80%9313?OpenDocument. Accessed 10 Jan 2019

Brimblecombe J, Ferguson M, Liberato S, O'Dea K. Characteristics of the community-level diet of aboriginal people in remote northern Australia. Med J Aust. 2013;198(7):380–4.

Davy C, Harfield S, McArthur A, Munn Z, Brown A. Access to primary health care services for indigenous peoples: a framework synthesis. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):163.

Commonwealth of Australia. Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. Closing the gap prime Minister's report 2018. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2018. https://www.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/reports/closing-the-gap-2018/sites/default/files/ctg-report-20183872.pdf?a=1. Accessed 7 Jan 2019

Dudgeon PW, Walker R, Scrine C, Shepherd CCJ, Calma T, et al. Effective strategies to strengthen the mental health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Canberra: Closing the Gap Clearinghouse; 2014. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/6d50a4d2-d4da-4c53-8aeb-9ec22b856dc5/ctgc-ip12-4nov2014.pdf.aspx?inline=true. Accessed 10 Jan 2019

Charles J. An evaluation and comprehensive guide to successful aboriginal health promotion. Austr Indigen Health Bull. 2015;16(1):1–8.

Hudson S. Evaluating indigenous programs: a toolkit for change. Evaluating indigenous programs: a toolkit for change. The Centre for Independent Studies; 2017. https://www.cis.org.au/app/uploads/2017/06/rr28.pdf. Accessed 13 Jan 2019

Hudson S. Mapping the indigenous program and funding maze. Centre for Independent Studies; 2016. https://www.cis.org.au/app/uploads/2016/08/rr18-Full-Report.pdf. Accessed 19 Jan 2019

UNICEF, World Health Organisation, International conference on primary health care. Declaration of Alma-Ata: international conference on primary health care. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1978. https://www.who.int/publications/almaata_declaration_en.pdf. Accessed 12 Jan 2019

Browne J, Adams K, Atkinson P, Gleeson D, Hayes R. Food and nutrition programs for aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Australians: an overview of systematic reviews. Aust Health Rev. 2017;17(4):1–9.

United Nations General Assembly. United Nations declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples. New York: United Nations General Assembly; 2008. https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf. Accessed 17 Jan 2019

Genat B, Browne J, Thorpe S, MacDonald C. Sectoral system capacity development in health promotion: evaluation of an aboriginal nutrition program. Health Promot J Austr. 2016;27(3):236–42.

Marley JV, Kitaura T, Atkinson D, Metcalf S, Maguire GP, et al. Clinical trials in a remote aboriginal setting: lessons from the BOABS smoking cessation study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):579.

Farnbach S, Eades AM, Fernando JK, Gwynn JD, Glozier N, et al. The quality of Australian indigenous primary health care research focusing on social and emotional wellbeing: a systematic review. Public Health Res Pract. 2017;27(4):e27341700.

Kelaher M, Luke J, Ferdinand A, Chamravi D, Ewen S, et al. An evaluation framework to improve aboriginal and Torres Strait islander health. Report. Carlton: Lowitja Institute; 2018. https://croakey.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Evaluation_Report_FINAL-copy.pdf. Accessed 9 Jan 2019

Morley S. What works in effective indigenous community-managed programs and organisations. Australian Institute of Family Studies: Melbourne; 2015. https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/sites/default/files/publication-documents/cfca-paper32-indigenous-programs.pdf. Accessed 11 Jan 2019

Beks H, Binder M, Kourbelis C, May N, Clark R, et al. Geographical analysis of evaluated chronic disease programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the primary healthcare setting: a scoping review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2018;16(12):2268–78.

Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Baldini Soares C, Khalil H, Parker D. Chapter 11: scoping reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. Joanna Briggs institute Reviewer's manual: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017. https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/. Accessed 16 Jan 2019.

National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Values and ethics: guidelines for ethical conduct in aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Health Research: NHMRC; 2003. https://nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/values-and-ethics-guidelines-ethical-conduct-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-health-research. Accessed 19 Jan 2019

Jamieson L, Paradies Y, Eades S, Chong A, Maple-Brown L, et al. Ten principles relevant to health research among indigenous Australian populations. Med J Aust. 2012;197(1):16–8.

Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI). Arc GIS arc map: release 10.6. Redlands: ESRI; 2018.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Remoteness structure. Canberra: ABS; 2018. http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/home/remoteness+structure. Accessed 8 Jan 2019

Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of New South Wales (AHaMR). 10 out of 10 deadly health stories: nutrition and physical activity: successful program from NSW aboriginal community controlled health services. Surry Hills: AHaMR; 2009. https://www.ahmrc.org.au/media/resources/public-health/chronic-disease-program/299-10-out-of-10-deadly-health-stories/file.html. Accessed 10 Jan 2019

Abbott P, Davison J, Moore L, Rubinstein R. Barriers and enhancers to dietary behaviour change for aboriginal people attending a diabetes cooking course. Health Promot J Austr. 2010;21(1):33–8.

Abbott PA, Davison JE, Moore LF, Rubinstein R. Effective nutrition education for aboriginal Australians: lessons from a diabetes cooking course. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012;44(1):55–9.

Adams K, Rumbiolo D, Charles S. Evaluation of Rumbalara's 'No more Dhonga' short course in giving up smokes. Aborig Isl Health Work J. 2006;30(5):20–1.

Askew DA, Togni SJ, Schluter PJ, Rogers L, Egert S, et al. Investigating the feasibility, acceptability and appropriateness of outreach case management in an urban aboriginal and Torres Strait islander primary health care service: a mixed methods exploratory study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:178.

Bailie RS, Robinson G, Kondalsamy-Chennakesavan SN, Halpin S, Wang Z. Investigating the sustainability of outcomes in a chronic disease treatment programme. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(6):1661–70.

Ballestas T, McEvoy S, Swift-Otero V, Unsworth M. A metropolitan aboriginal podiatry and diabetes outreach clinic to ameliorate foot-related complications in aboriginal people. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2014;38(5):492–3.

Barrett E, Salem L, Wilson S, O'Neill C, Davis K, et al. Chronic kidney disease in an aboriginal population: a nurse practitioner-led approach to management. Aust J Rural Health. 2015;23(6):318–21.

Battersby MW, Kit JA, Prideaux C, Harvey PW, Collins JP, et al. Implementing the flinders model of self-management support with aboriginal people who have diabetes: findings from a pilot study. Aust J Prim Health. 2008;14(1):66–74.

Boyle J, Hollands G, Beck S, Hampel G, Wapau H, et al. Process evaluation of a pilot evidence-based polycystic ovary syndrome clinic in the Torres Strait. Aust J Rural Health. 2017;25(3):175–81.

Brazionis L, Jenkins A, Keech A, Ryan C, Brown A, et al. Diabetic retinopathy in a remote indigenous primary healthcare population: a central Australian diabetic retinopathy screening study in the telehealth eye and Associated Medical Services network project. Diabet Med. 2018;35(5):630–9.

Burgess CP, Bailie RS, Connors CM, Chenhall RD, McDermott RA, et al. Early identification and preventive care for elevated cardiovascular disease risk within a remote Australian aboriginal primary health care service. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:24.

Canuto K, Cargo M, Li M, D’Onise K, Esterman A, McDermott R. Pragmatic randomised trial of a 12-week exercise and nutrition program for aboriginal and Torres Strait islander women: clinical results immediate post and 3 months follow-up. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):933.

Canuto K. Evaluating the effectiveness of the aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Women’s fitness program: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Adelaide: University of South Australia; 2013.

Canuto KJ, Spagnoletti B, McDermott RA, Cargo M. Factors influencing attendance in a structured physical activity program for aboriginal and Torres Strait islander women in an urban setting: a mixed methods process evaluation. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:11.

Chan LC, Ware R, Kesting J, Marczak M, Good D, et al. Short term efficacy of a lifestyle intervention programme on cardiovascular health outcome in overweight indigenous Australians with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus. The healthy lifestyle programme (HELP). Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;75(1):65–71.

Clark RA, Fredericks B, Adams M, Howie-Esquivel J, Dracup K, et al. A collaborative approach to developing culturally appropriate heart failure self-care tools for indigenous Australians using multi-media technology. Circulation. 2014;130(Suppl 2):A13530.

Clark RA, Fredericks B, Buitendyk NJ, Adams MJ, Howie-Esquivel J, et al. Development and feasibility testing of an education program to improve knowledge and self-care among aboriginal and Torres Strait islander patients with heart failure. Rural Remote Health. 2015;15(3):3231.

Clifford A, Shakeshaft A, Deans C. Training and tailored outreach support to improve alcohol screening and brief intervention in aboriginal community controlled health services. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2013;32(1):72–9.

Crengle S, Luke JN, Lambert M, Smylie JK, Reid S, et al. Effect of a health literacy intervention trial on knowledge about cardiovascular disease medications among indigenous peoples in Australia, Canada and New Zealand. BMJ Open. 2018;8(1):e018569.

D'Abbs P, Togni S, Rosewarne C, Boffa J. The grog mob: lessons from an evaluation of a multi-disciplinary alcohol intervention for aboriginal clients. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2013;37(5):450–6.

Davey M, Moore W, Walters J. Tasmanian aborigines step up to health: evaluation of a cardiopulmonary rehabilitation and secondary prevention program. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:349.

DiGiacomo M, Davidson PM, Davison J, Moore L, Abbott P. Stressful life events, resources, and access: key considerations in quitting smoking at an aboriginal medical service. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2007;31(2):174–6.

Dimer L, Jones J, Dowling T, Cheetham C, Maiorana A, et al. Heart health: new ways to deliver cardiac rehabilitation. Aust Nurs J. 2010;18(6):41.

Dimer L, Jones J, Dowling T, Cheetham C, Maiorana A, et al. Heart health for our people by our people: a culturally appropriate WA CR program. Heart Lung Circ. 2012;21(10):651–2.

Dimer L, Dowling T, Jones J, Cheetham C, Thomas T, et al. Build it and they will come: outcomes from a successful cardiac rehabilitation program at an aboriginal medical service. Aust Health Rev. 2013;37(1):79–82.

Maiorana A, Dimer L, Dowling T, Jones J, Thomas T, et al. Outcomes from an aboriginal medical service based cardiac rehabilitation program. Heart Lung Circ. 2012;21(10):659.

Maiorana A, Chevis E, Venables M, Dubrawski K, Dowling T, et al. Reducing inequities in aboriginal Australian heart health through culturally specific cardiac rehabilitation. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22(1):15.

Eades SJ, Sanson-Fisher RW, Wenitong M, Panaretto K, D'Este C, et al. An intensive smoking intervention for pregnant aboriginal and Torres Strait islander women: a randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust. 2012;197(1):42–6.

Gould G, McGechan A, Van der Zwan R. Give up the smokes - a smoking cessation program for indigenous Australians. In: Proceedings of the 10th National Rural Health Conference, 2009 May 17–20. Cains: National Rural Health Alliance; 2009. https://www.ruralhealth.org.au/10thNRHC/10thnrhc.ruralhealth.org.au/papers/docs/Gould_Gillian_D9.pdf. Accessed 5 Jan 2019.

Gracey M, Bridge E, Martin D, Jones T, Spargo RM, et al. An aboriginal-driven program to prevent, control and manage nutrition-related “lifestyle” diseases including diabetes. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2006;15(2):178–88.

Isaacs A, Lampitt B. The Koorie Men's health day: an innovative model for early detection of mental illness among rural aboriginal men. Australas Psychiatry. 2014;22(1):56–61.

Ju X, Brennan D, Parker E, Mills H, Kapellas K, Jamieson L. Efficacy of an oral health literacy intervention among indigenous Australian adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemio. 2017;45(5):413–26.

Kapellas K, Do LG, Mark Bartold P, Skilton MR, Maple-Brown LJ, et al. Effects of full-mouth scaling on the periodontal health of indigenous Australians: a randomised controlled trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40(11):1016–24.

Kapellas K, Maple-Brown LJ, Bartold PM, Brown A, O'Dea K, et al. O162 effect of a periodontal intervention on pulse wave velocity in indigenous Australians with periodontal disease: the PerioCardio randomised controlled trial. Glob Heart. 2014;9(Suppl 1):44.

Kapellas K, Maple-Brown LJ, Jamieson LM, Do LG, O'Dea K, et al. Effect of periodontal therapy on arterial structure and function among aboriginal Australians: a randomised, controlled trial. Hypertension. 2014;64(4):702–8.

Kapellas K, Mejia G, Bartold PM, Skilton MR, Maple-Brown LJ, et al. Periodontal therapy and glycaemic control among individuals with type 2 diabetes: reflections from the PerioCardio study. Int J Dent Hyg. 2017;15(4):42–51.

Kowanko I, Helps Y, Harvey P, Battersby M, McCurry B, et al. Chronic condition management strategies in aboriginal communities: final report 2011. Adelaide: Flinders University and the Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia; 2012. http://www.flinders.edu.au/medicine/fms/sites/FHBHRU/documents/publications/CCM%20Aboriginal%20Communities%20Report-WEB1.pdf. Accessed 7 Jan 2019

Lawton P, Wright G, Hore B, McLaughlin J, Cass A. Analysis of longitudinal clinical data to evaluate the impact and effectiveness of a nurse-led Ckd program. Nephrology. 2016;21:104.

Longstreet D, Heath D, Savage I, Vink R, Panaretto K. Estimated nutrient intake of urban indigenous participants enrolled in a lifestyle intervention program. Nutr Diet. 2008;65(2):128–33.

Marley JV, Atkinson D, Kitaura T, Nelson C, Gray D, et al. The be our ally beat smoking (BOABS) study, a randomised controlled trial of an intensive smoking cessation intervention in a remote aboriginal Australian health care setting. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:32.

McDermott RA, Schmidt B, Preece C, Owens V, Taylor S, et al. Community health workers improve diabetes care in remote Australian indigenous communities: results of a pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:68.

Schmidt B, Campbell S, McDermott R. Community health workers as chronic care coordinators: evaluation of an Australian indigenous primary health care program. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2016;40(Suppl 1):107–14.

Segal L, Nguyen H, Schmidt B, Wenitong M, McDermott RA. Economic evaluation of indigenous health worker management of poorly controlled type 2 diabetes in North Queensland. Med J Aust. 2016;204(5):1961.

Mills K, Gatton ML, Mahoney R, Nelson A. 'Work it out': evaluation of a chronic condition self-management program for urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, with or at risk of cardiovascular disease. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):680.

Nagel T, Thompson C. Motivational care planning: self-management in indigenous mental health. Aust Fam Physician. 2008;37(12):996–1000.

Nagel T, Robinson G, Trauer T, Condon J. An approach to treating depressive and psychotic illness in indigenous communities. Aust J Prim Health. 2008;14(1):17–24.

Quinn E, O'Hara BJ, Ahmed N, Winch S, McGill B, et al. Enhancing the get healthy information and coaching service for aboriginal adults: evaluation of the process and impact of the program. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16(1):168.

Read P, Lothian R, Chronister K, Gilliver R, Kearley J, et al. Delivering direct acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C to highly marginalised and current drug injecting populations in a targeted primary health care setting. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;47:209–15.

Shephard MDS. Cultural and clinical effectiveness of the 'QAAMS' point-of-care testing model for diabetes management in Australian aboriginal medical services. Clin Biochem Rev. 2006;27(3):161–70.

Shephard M, Shephard A, McAteer B, Regnier T, Barancek K. Results from 15years of quality surveillance for a National Indigenous Point-of-Care Testing Program for diabetes. Clin Biochem. 2017;50(18):1159–63.

Spaeth BA, Shephard MD, Schatz S. Point-of-care testing for haemoglobin A1c in remote Australian indigenous communities improves timeliness of diabetes care. Rural Remote Health. 2014;14(4):2849.

Shephard MDS, Mazzachi BC, Shephard AK, Burgoyne T, Dufek A, et al. Point-of-care testing in aboriginal hands - a model for chronic disease prevention and management in indigenous Australia. Point Care. 2006;5(4):168–76.

Sinclair C, Stokes A, Jeffries-Stokes C, Daly J. Positive community responses to an arts–health program designed to tackle diabetes and kidney disease in remote aboriginal communities in Australia: a qualitative study. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2016;40(4):307–12.

Ski C, Vale M, Thompson D, Jelinek M, Scott I, et al. The coaching patients on achieving cardiovascular health (COACH) Programme: reducing the treatment gap between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians. Heart Lung Circ. 2017;26(Suppl 2):336.

Spurling GKP, Askew DA, Hayman NE, Hansar N, Cooney AM, et al. Retinal photography for diabetic retinopathy screening in indigenous primary health care: the Inala experience. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2010;34(Suppl 1):30–S3.

Spurling GKP, Hayman NE, Cooney AL. Adult health checks for indigenous Australians: the first year's experience from the Inala indigenous health service. Med J Aust. 2009;190(10):562–4.

Stevens JA, Dixon J, Binns A, Morgan B, Richardson J, Egger G. Shared medical appointments for aboriginal and Torres Strait islander men. Aust Fam Physician. 2016;45(6):425–9.

Sun J, Buys N. Effectiveness of participative community singing intervention program on promoting resilience and mental health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia. In: Olisah V, editor. Essential notes in psychiatry. Croatia: InTech; 2012. p. 245–52.

Sun J, Buys N. Participatory community singing program to enhance quality of life and social and emotional well-being in aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Australians with chronic diseases. Int J Disabil Hum Dev. 2013;12(3):317–23.

Sun J, Buys N. Effectiveness of a participative community singing program to improve health behaviors and increase physical activity in Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Int J Disabil Hum Dev. 2013;12(3):297–304.

Sun J, Buys N. Can community singing program promote social and emotional wellbeing in aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Australians? J Altern Complement. 2013;5(2):137–42.

Sun J, Buys NJ. Improving aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Australians ' well-being using participatory community singing approach. Int J Disabil Hum Dev. 2013;12(3):305–16.

Sun J, Buys N. Using participative community singing program to improve health behaviours in Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;5(2):103–9.

Sun J, Buys N. Using community singing as a culturally appropriate approach to prevent depression in aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Australians. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;5(2):111–7.

Sun J, Buys N. Effects of community singing program on mental health outcomes of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: a meditative approach. Am J Health Promot. 2016;30(4):259–63.

Swain L. Improving medication management for aboriginal and Torres islander people by investigating the use of Home medicines review. Sydney: University of Sydney; 2016.

Swain LS, Barclay L. Exploration of aboriginal and Torres Strait islander perspectives of Home medicines review. Rural Remote Health. 2015;15:3009.

Tane MP, Hefler M, Thomas DP. An evaluation of the “Yaka Ŋarali” tackling indigenous smoking program in East Arnhem Land: Yolŋu people and their connection to ŋarali’. Health Promot J Austr. 2018;29(1):10–7.

Togni SJ. The Uti Kulintjaku project: the path to clear thinking. An evaluation of an innovative, aboriginal-led approach to developing bi-cultural understanding of mental health and wellbeing. Aust Psychol. 2017;52(4):268–79.

Treloar C, Hopwood M, Cama E, Saunders V, Jackson LC, et al. Evaluation of the deadly liver mob program: insights for roll-out and scale-up of a pilot program to engage aboriginal Australians in hepatitis C and sexual health education, screening, and care. Harm Reduct J. 2018;15(1):1-12.

Truasheim S. Cultural safety for aboriginal and Torres Strait islander adults within Australian music therapy practices. Aust J Music Ther. 2014;24:135–47.

Verrier L, Brooks J, Foley J, Maclean M. Implementing a culturally responsive model of perinatal mental health care in a rural aboriginal community in Western Australia. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2013;16:39–40.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). 3238.0.55.001 - estimates of aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Australians, June 2016. Canberra: ABS. p. 2016. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/3238.0.55.001. Accessed 10 Jan 2019

Lavallee LF, Poole JM. Beyond recovery: colonisation, health and healing for indigenous people in Canada. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2010;8(2):271–81.

Ataera-Minster J, Trowland H. Te Kaveinga –mental health and wellbeing of Pacific peoples - results from the new Zealand Mental Health Monitor & Health and lifestyles survey. Wellington: Health Promotion Agency; 2018. https://www.hpa.org.nz/sites/default/files/FinalReport-TeKaveinga-Mental%20health%20and%20wellbeing%20of%20Pacific%20peoples-Jun2018.pdf. Accessed 7 Jan 2019

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). 3301.0 - births, Australia, 2017. Canberra: ABS; 2018. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/3301.0Main%20Features62017?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=3301.0&issue=2017&num=&view. Accessed 9 Jan 2019.

Campbell P, Biddle N, Paradies Y. Indigenous identification and transitions in Australia: exploring new findings from a linked micro-dataset. Population. 2019;73(4):771–96.

Arriagada P. First nations, Métis and Inuit women. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2016. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-503-x/2015001/article/14313-eng.htm. Accessed 7 Jan 2019.

Lokuge K, Thurber K, Calabria B, Davis M, McMahon K, et al. Indigenous health program evaluation design and methods in Australia: a systematic review of the evidence. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2017;41(5):480–2.

Campbell MA, Hunt J, Scrimgeour DJ, Davey M, Jones V. Contribution of aboriginal community-controlled health services to improving aboriginal health: an evidence review. Aust Health Rev. 2018;42(2):218.

Panaretto KS, Dellit A, Hollins A, Wason G, Sidhom C, et al. Understanding patient access patterns for primary health-care services for aboriginal and islander people in Queensland: a geospatial mapping approach. Aust J Prim Health. 2017;23(1):37–45.

Harfield SG, Davy C, McArthur A, Munn Z, Brown A, et al. Characteristics of indigenous primary health care service delivery models: a systematic scoping review. Glob Health. 2018;14(1):12.

Williams M. Ngaa-bi-nya aboriginal and Torres Strait islander program evaluation framework. Eval J Austr. 2018;18(1):6–20.

Doyle K, Cleary M, Blanchard D, Hungerford C. The Yerin dilly bag model of Indigenist Health Research. Qual Health Res. 2017;27(9):1288–301.

Bainbridge R, Tsey K, McCalman J, Kinchin I, Saunders V, et al. No one’s discussing the elephant in the room: contemplating questions of research impact and benefit in aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Australian health research. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):696.

Derrick GE, Hayen A, Chapman S, Haynes AS, Webster BM, et al. A bibliometric analysis of research on indigenous health in Australia, 1972-2008. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2012;36(3):269–73.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Nikki May for developing, testing and running the search strategies for the databases and undertaking a search for unpublished studies. We also acknowledge the support from librarians, Dorothy Rooney and Fiona Russell. We wish to thank Jason Kanoa and John Bell for contributing to the conception of this review in their capacities as CEO of Gunditjmara Aboriginal Cooperative (Warrnambool, Victoria) and CEO of Dhauwurd-Wurrung Elderly and Community Health Service (Portland, Victoria) respectively.

Funding

This review was part of a broader project which received funding from the Western Alliance Academic Health Science Centre (Project WA-733531_Beks). The funding body had no role in the design of the review, analysis and interpretation of articles. Robyn A Clark is supported by a Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship (APP ID. 100847). Hannah Beks, Marley J Binder, Geraldine Ewing, and Vincent L Versace are funded by the Australian Government Department of Health Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training (RHMT) Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HB led the scoping review design, screening of data, data extraction, analysis of data, and drafting of the manuscript. MJB and CK were involved in the scoping review design, screening of data, data extraction, analysis of data and drafting of the manuscript. GE was involved in data extraction, analysis of data and drafting of the manuscript. JC and YP were involved in the analysis of data and drafting of the manuscript. RC and VLV were involved in the scoping review design, analysis of data, and drafting of the manuscript which included a review for cultural appropriateness in the reporting of outcomes. VLV conceived the geographical aspect of the review and produced the geographical outputs and analysis. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

PRISMA 2009 Checklist. This file contains the PRISMA checklist and co-relating page numbers to the items for reporting. (DOCX 25 kb)

Additional file 2:

Electronic search results and terms. This file contains a table of search results and terms used to retrieve studies from databases (DOCX 43 kb)

Additional file 3:

Excluded Studies. This file contains a table of excluded studies and reasons for exclusion. (DOCX 68 kb)

Additional file 4:

Data extraction: evidence of partnerships and reference to ethical guidelines. This file contains a table of data extracted in relation to the secondary objectives of this review; scoping evidence of partnerships with Indigenous organizations and ethical approaches to undertaking a program evaluation. (DOCX 95 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Beks, H., Binder, M.J., Kourbelis, C. et al. Geographical analysis of evaluated chronic disease programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the Australian primary health care setting: a systematic scoping review. BMC Public Health 19, 1115 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7463-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7463-0