Abstract

Background

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a risk factor for early neurological deterioration (END) in acute ischemic stroke. The prothrombotic protein fibrinogen is frequently elevated in patients with diabetes, and may be associated with poorer prognoses. We evaluated whether fibrinogen is associated with END in patients with diabetes after acute ischemic stroke.

Methods

We included 3814 patients from a single hospital database admitted within 72 h of onset of ischemic stroke. END was defined as an increase in the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) ≥2 within 7 days post-admission. In the total population (END, n = 661; non-END, n = 3153), univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to assess fibrinogen as an independent predictor for END. We then performed propensity score matching and univariate analyses for DM (END, n = 261; non-END, n = 522) and non-DM populations (END, n = 399; non-END, n = 798). Multiple logistic analyses were performed after matching for fibrinogen as a risk factor in each subgroup.

Results

Fibrinogen levels were higher in the END group than in the non-END group (367 ± 156 mg/dL vs. 347 ± 122 mg/dL, p = 0.002), though they were not associated with END in logistic regression analyses. Fibrinogen levels were found to be an independent predictor for END, but only in the DM population (fibrinogen levels 300–599 mg/dL, odds ratio: 1.618, 95% confidence interval: 1.037–2.525, p = 0.034, fibrinogen levels ≥600 mg/dL, 2.575, 1.018–6.514, p = 0.046; non-DM population, p = 0.393). The diabetes-fibrinogen interaction for the entire cohort was p = 0.101.

Conclusions

Elevated fibrinogen is dose-dependently associated with END in patients with diabetes following acute ischemic stroke.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Diabetes mellitus (DM) and hyperglycemia negatively affect the outcome and pathophysiology of acute ischemic stroke. The associations between DM and early neurological deterioration (END) [1, 2], more comorbidities [3], severe handicap and disability [4, 5], and increased mortality [3], have been repeatedly reported in both case-control [6] and cohort studies [7]. When the effects of hyperglycemia are included, these patients also present with more severe lesion size [8], more symptomatic intracranial hemorrhages [9, 10], edema [11], and mortality [12]. Although END is more frequently encountered in diabetic patients, the specific mechanisms underlying how DM promotes END are among the least clear. In clinical practice, being able to anticipate END would allow for more timely intervention; thus, gaining further insight into the mechanisms of END specific to patients with DM would improve the ability to identify and intervene in END in a population seemingly more susceptible to it. One possible mechanism linking DM with adverse outcomes of stroke involves fibrinogen, a prothrombotic protein, and acute phase reactant that is consistently elevated in patients with diabetes [13, 14]. In fact, a large body of evidence identifies fibrinogen as a mediator in the development of coronary artery thrombi and future cardiac events [15, 16]. However, the association of hyperfibrinogenemia and END in acute ischemic stroke has not yet been demonstrated. In this study, we evaluated whether elevated fibrinogen levels in patients with diabetes and acute ischemic stroke are associated with END in a large, single-center population.

Methods

Study population

We performed a retrospective study that was approved by the Institutional Review Board, and performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments, incorporating consecutive patients enrolled in a hospital stroke database. From this database, we reviewed consecutive patients from Jan. 2000 to Dec. 2015. Among them, we included 3814 patients with acute ischemic stroke within 72 h of onset, and with available National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) data.

Data acquisition

For this study, the diagnosis of DM was defined as either a prior diagnosis of diabetes, or glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels >6.1% at admission, according to a previous study which showed that prediabetic levels of hba1c >6.1% were associated with increased stroke recurrence [17]. Lab data concerning the hemostatic profiles such as fibrinogen, fibrin degradation products (FDP), D-dimer, and classic stroke risk factors were obtained on the day of admission, before initiation of intravenous tissue plasminogen activators for those who were applicable. Acute inflammatory markers, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and standard C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were included in the analysis, to compare with fibrinogen. Components of metabolic syndrome were also analyzed. Lab data routinely taken to evaluate diabetic status, such as fasting glucose levels, urine glucose, urine protein, and HbA1c levels were also included in the analysis. Trial of Org 10,172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) classification, and NIHSS scores on admission and at discharge were also collected from the database.

Propensity score matching and statistical analysis

END was defined as a NIHSS score increase of 2 or more within 7 days after admission. A number of studies have, for the definition of END, used an increase of ≥2 points in the total NIHSS score within 7 days [18], as modified from a previous study. We have incorporated such sensitive criteria to define END for such subtle changes call for action in clinical practice. Because END in patients with acute ischemic stroke can be influenced by a greater initial NIHSS and TOAST classification, we used propensity score matching to adjust for well-known confounding factors. First, among the 3814 patients with acute stroke, we performed univariate and multivariate analyses to document the effects of fibrinogen and other predictive factors of END. Multivariate analysis was performed, adjusting for age, sex, presence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, initial NIHSS score, and TOAST classification. The p value for the diabetes status x fibrinogen level interaction was also calculated in the logistic regression model. For subgroup analysis, the patients were divided into DM (n = 1360) and non-DM (n = 2454) populations. In each subgroup, a 1:2 propensity score matching of END patients and non-END patients was performed, adjusting for age, sex, initial NIHSS score, and TOAST classification (Additional file 1: Figure S1A-B). Differences between the two groups were analyzed before and after propensity score matching, using a χ2 test for categorical variables and Student’s t-test for continuous variables. Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed, adjusting for baseline clinical variables known to be associated with END such as age, sex, hypertension, initial NIHSS, and TOAST classification, as well as with potentially significant factors determined in the univariate analysis (p < 0.005), to verify the significance of fibrinogen levels on END. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20 software (Chicago, IL).

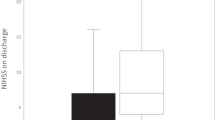

Results

Among 3814 patients with acute stroke, 661 cases (17.3%) experienced early neurological deterioration. Patients in the END group were significantly older (65.3 ± 12.6 vs. 63.5 ± 13.5, p = 0.001), and more frequently had a history of DM (39.6% vs. 34.8%, p = 0.019), a history of hypertension (70.0% vs. 65.8%, p = 0.039), a higher initial NIHSS (8.2 ± 6.7 vs. 5.6 ± 6.3, p < 0.001), higher fasting glucose (151 ± 66 vs. 144 ± 63 mg/dL, p = 0.005), higher urine protein positivity (22.7% vs. 14.6%, p < 0.001), and higher fibrinogen levels (367 ± 156 vs. 347 ± 122 mg/dL, p = 0.002) (Table 1). In the multiple regression analysis of the total population, higher fibrinogen levels were not significantly associated with END after adjusting for confounders (p = 0.195) (Table 2). The interaction between diabetes status and fibrinogen levels regarding END was not statistically significant in the entire cohort (p = 0.101).

There were 1360 diabetic and 2454 non-diabetic patients. In the DM population (END = 262, non-END = 1098), a diagnosis of hypertension (81.6% vs. 74.6%, p = 0.017), initial NIHSS (10.4 ± 10.6 vs. 3.6 ± 5.7, p < 0.001), urine protein positivity (35.1% vs. 21.2%, p < 0.001), and fibrinogen levels (392.9 ± 204.2 mg/dL, p = 0.012) were significantly higher in the END population versus the non-END population (Table 3). Propensity score matching was performed for age, sex, initial NIHSS, and TOAST classification, with a relative multivariate imbalance measure L1 of 0.621 before matching, and 0.609 after matching. No covariate exhibited a large imbalance. After matching, proteinuria (34.7% vs. 23.4%, p = 0.007, and hyperfibrinogenemia (392.8 ± 204.6 vs. 361 ± 123.1 mg/dL, p = 0.009) were still significantly associated with END (Table 3). In the propensity score-matched population, further logistic regression analysis adjusting for age, sex, hypertension, TOAST classification, and positive proteinuria was done, and fibrinogen was significantly associated with END in the DM population (fibrinogen <300 mg/dL as reference; fibrinogen levels 300 ~ 599 mg/dL, odds ratio: 1.618, 95% confidence interval: 1.037–2.525, p = 0.034, fibrinogen levels ≥600 mg/dL, 2.575, 1.018–6.514, p = 0.046) (Table 4).

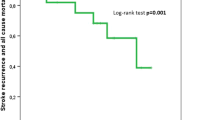

In the non-DM population (END = 399, Non-END = 2055), age (65.3 ± 13.2 vs. 62.7 ± 14.3, p < 0.001), initial NIHSS (8.4 ± 6.8 vs. 5.6 ± 6.3, p < 0.001), and fasting glucose levels (125.6 ± 30.9 vs. 122.1 ± 29.7 mg/dL, p = 0.036) were significantly higher in the END group, as were differences in TOAST classification (p < 0.001) (Additional file 2: Table S1). Propensity score matching was performed for age, sex, initial NIHSS, and TOAST classification, with a relative multivariate imbalance measure L1 of 0.581 before matching, and 0.525 after matching. No covariate exhibited a large imbalance. After matching, TOAST classification (p = 0.003), elevated total cholesterol (179.5 ± 41.3 vs. 173.6 ± 38.4 mg/dL, p = 0.015), and elevated low density lipoprotein (108.2 ± 37.4 vs. 102.8 ± 34.3 mg/dL, p = 0.015) were significantly associated with END (Additional file 2: Table S1). In further regression analysis in the matched population, including age, male sex, presence of hypertension, initial NIHSS, TOAST classification, and total cholesterol levels as covariables, fibrinogen did not prove to be associated with END (p = 0.393) (Additional file 2: Table S2).

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that hyperfibrinogenemia in patients with acute stroke and DM is associated with END, using both propensity score matching and multiple logistic regression analysis. Whereas the influence of hyperfibrinogenemia on END was consistently seen in the DM subgroup, it disappeared in the non-DM subgroup.

Hyperfibrinogenemia itself may directly induce a higher frequency of END in diabetic individuals through activation of the coagulation cascade. Fibrinogen forms fibrin clots as part of the final common stages of both the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways of the coagulation cascade [19]. Atherogenesis and the growth of atheromatous lesions are also initiated in part by fibrin deposition [20, 21]. Fibrinogen also facilitates platelet aggregation by binding to the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor, increasing its reactivity [22].

Hyperfibrinogenemia may also indirectly reflect a prothrombotic condition induced by hyperinsulinemia and prolonged glycation. Levels of fibrinogen in diabetic patients correlate with insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome [13]. Prolonged glycation also induces a prothrombotic condition. Studies on fibrin clot structure under diabetic conditions have shown fibrinogen to be glycated in vivo [23], causing a change in the fibrin clot structure that reduces permeability [24], decreases fibrinolysis [25], and decreases α-chain crosslinking [26]. Thus, the effects of insulin resistance and prolonged glycation increase the risk of thrombosis, which underpins the development of vascular disease [27]. These studies lead us to assume that fibrinogen levels may represent a marker of platelet aggregation or progression to a prothrombotic phenotype in patients with diabetes [27].

This is the first study to link diabetic hyperfibrinogenemia to a higher frequency of END after ischemic stroke. Epidemiological studies have established that elevated fibrinogen levels are strongly and independently correlated with the risks of coronary arterial disease (CAD), stroke, and peripheral arterial disease [16, 28,29,30,31]. In stroke, carotid artery stenosis is significantly associated with elevated fibrinogen levels [32], and placebo data analysis in the Stroke Treatment with Ancrod Trial (STAT) and European Stroke Treatment with Ancrod Trial (ESTAT) has shown that plasma fibrinogen levels at stroke onset are independently associated with a poor functional outcome [33]. However, it has not been reported that hyperfibrinogenemia in patients with diabetes is associated with END in the acute stroke period.

It is conceivable that stronger antiplatelet treatments might be needed for patients with diabetes and hyperfibrinogenemia following acute ischemic stroke. Of note, elevated fibrinogen levels in our group of patients with diabetes may be linked to antiplatelet resistance, which may in turn result in END. Previous large scale trials, such as the Japanese Primary Prevention of Atherosclerosis with Aspirin for Diabetes (JPAD) trial [34], and the Prevention of Progression of Arterial Disease and Diabetes (POPAPAD) trial [35], have shown low efficacy of aspirin monotherapy for prevention of cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes. In addition, recent data show that responses to clopidogrel in patients with diabetes are suboptimal [36]. Such data suggest that diabetes is associated with considerable resistance to aspirin and clopidogrel therapy, and such insufficient antiplatelet responses could be an underlying causal factor for the frequent END observed in this population. In accordance with the elevated fibrinogen levels in our data, a recent study evaluating platelet aggregation characteristics in acute coronary syndrome found antiplatelet drug resistance to be significantly associated with metabolic syndrome, and fibrinogen levels and high sensitivity-CRP were higher in this population [37]. Serum fibrinogen levels appeared to be strongly associated with drug resistance [37]. In this case, elevated fibrinogen levels may call for more radical choices for antiplatelet therapy in such a population.

Apart from the antiplatelet issue, the idea that reduced fibrin, which is formed by fibrinogen in blood, may reduce blood viscosity, improve blood flow, and help remove the blood clot blocking the artery and re-establish blood flow has inspired clinical trials testing the therapeutic effects of the fibrin-depleting agents ancrod and defibrase [38]. In eight trials involving 5701 patients, fibrin-depleting agents marginally reduced the proportion of patients who were dead or disabled at the end of follow-up, and there were fewer stroke recurrences in the treatment group than in the control group. However, symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage was about twice as common in the treatment group compared with the control group [38]. The use of fibrin-depleting agents to reduce blood viscosity in patients with DM and elevated fibrinogen at risk for END holds similar problems. Plasma fibrinogen levels are associated with silent cerebrovascular lesions [39], and although this relationship may be evidence that increased viscosity by fibrinogen is a risk factor for stroke, deep white matter hyperintensities, on the other hand, are a known risk factor for intracerebral hemorrhage [40]. Accordingly, the use of fibrin-depleting agents in patients with DM may confer a higher risk of hemorrhagic complications. Thus, while the selective use of fibrin-depleting agents in patients with DM and END may be considered, further clinical studies to address the risks are needed prior to making such treatment a recommendation.

We acknowledge that our study has limitations. First, due to the retrospective nature of the study, there may be selection bias. We tried to minimize this issue by maximizing the number of patients included in the study and including adequate propensity score matching. Second, our somewhat long temporal definition of END (<7 days) incorporates a range of heterogeneous underlying mechanisms, and different definitions are used in other reports. Due to the retrospective nature and large number of enrolled patients in the study, the heterogeneity of END could not be addressed in this study. Third, because of the focus on lab data in this study, medication factors and imaging variables such as intracranial occlusion, stenosis, or diffusion weighted image volume were not included for analysis. However, variables that may have similar implications such as TOAST classification, and NIHSS scores were included, and the large patient numbers included may supplement such limitations. We hope to address these issues in later prospective studies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, hyperfibrinogenemia at admission in patients with acute ischemic stroke and DM is independently associated with END. This finding suggests that an elevated fibrinogen level is a marker of a prothrombotic or antiplatelet-resistant condition related to DM that could affect the patient’s prognosis. On the other hand, these results also reveal a category of patients wherein fibrin-depleting therapy could be significantly more effective.

Abbreviations

- CAD:

-

Coronary arterial disease

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- END:

-

Early neurological deterioration

- ESR:

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- FDP:

-

Fibrin degradation products

- HbA1c:

-

Glycated hemoglobin

- NIHSS:

-

National Institute of Health Stroke Scale

- TOAST:

-

Trial of Org 10,172 in acute stroke treatment

References

Davalos A, Toni D, Iweins F, Lesaffre E, Bastianello S, Castillo J. Neurological deterioration in acute ischemic stroke: potential predictors and associated factors in the European cooperative acute stroke study (ECASS) I. Stroke. 1999;30(12):2631–6.

Kim BJ, Park J-M, Kang K, Lee SJ, Ko Y, Kim JG, Cha J-K, Kim D-H, Nah H-W, Han M-K, et al. Case Characteristics, Hyperacute Treatment, and Outcome Information from the Clinical Research Center for Stroke-Fifth Division Registry in South Korea. J Stroke. 2015;17(1):38–53.

Kamalesh M, Shen J, Eckert GJ. Long term postischemic stroke mortality in diabetes: a veteran cohort analysis. Stroke. 2008;39(10):2727–31.

Megherbi SE, Milan C, Minier D, Couvreur G, Osseby GV, Tilling K, Di Carlo A, Inzitari D, Wolfe CD, Moreau T, et al. Association between diabetes and stroke subtype on survival and functional outcome 3 months after stroke: data from the European BIOMED Stroke Project. Stroke. 2003;34(3):688–94.

Lee S-J, Hong JM, Lee M, Huh K, Choi JW, Lee JS. Cerebral Arterial Calcification Is an Imaging Prognostic Marker for Revascularization Treatment of Acute Middle Cerebral Arterial Occlusion. J Stroke. 2015;17(1):67–75.

Barber M, Wright F, Stott DJ, Langhorne P. Predictors of early neurological deterioration after ischaemic stroke: a case-control study. Gerontology. 2004;50(2):102–9.

Weimar C, Mieck T, Buchthal J, Ehrenfeld CE, Schmid E, Diener HC. Neurologic worsening during the acute phase of ischemic stroke. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(3):393–7.

Els T, Klisch J, Orszagh M, Hetzel A, Schulte-Monting J, Schumacher M, Lucking CH. Hyperglycemia in patients with focal cerebral ischemia after intravenous thrombolysis: influence on clinical outcome and infarct size. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002;13(2):89–94.

Lansberg MG, Albers GW, Wijman CA. Symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage following thrombolytic therapy for acute ischemic stroke: a review of the risk factors. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;24(1):1–10.

Demchuk AM, Morgenstern LB, Krieger DW, Linda Chi T, Hu W, Wein TH, Hardy RJ, Grotta JC, Buchan AM. Serum glucose level and diabetes predict tissue plasminogen activator-related intracerebral hemorrhage in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 1999;30(1):34–9.

Berger L, Hakim AM. The association of hyperglycemia with cerebral edema in stroke. Stroke. 1986;17(5):865–71.

Candelise L, Landi G, Orazio EN, Boccardi E. Prognostic significance of hyperglycemia in acute stroke. Arch Neurol. 1985;42(7):661–3.

Meigs JB, Mittleman MA, Nathan DM, Tofler GH, Singer DE, Murphy-Sheehy PM, Lipinska I, D'Agostino RB, Wilson PW. Hyperinsulinemia, hyperglycemia, and impaired hemostasis: the Framingham Offspring Study. JAMA. 2000;283(2):221–8.

Dunn EJ, Ariens RA. Fibrinogen and fibrin clot structure in diabetes. Herz. 2004;29(5):470–9.

Koenig W. Fibrin(ogen) in cardiovascular disease: an update. Thromb Haemost. 2003;89(4):601–9.

Ernst E. Fibrinogen as a cardiovascular risk factor--interrelationship with infections and inflammation. Eur Heart J. 1993;14 Suppl K:82–7.

Wu S, Shi Y, Wang C, Jia Q, Zhang N, Zhao X, Liu G, Wang Y, Liu L, Wang Y, et al. Glycated hemoglobin independently predicts stroke recurrence within one year after acute first-ever non-cardioembolic strokes onset in A Chinese cohort study. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e80690.

Kanamaru T, Suda S, Muraga K, Okubo S, Watanabe Y, Tsuruoka S, Kimura K. Albuminuria predicts early neurological deterioration in patients with acute ischemic stroke. J Neurol Sci. 2017;372:417–20.

Herrick S, Blanc-Brude O, Gray A, Laurent G. Fibrinogen. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1999;31(7):741–6.

Forsyth CB, Solovjov DA, Ugarova TP, Plow EF. Integrin alpha(M)beta(2)-mediated cell migration to fibrinogen and its recognition peptides. J Exp Med. 2001;193(10):1123–33.

Tousoulis D, Papageorgiou N, Androulakis E, Briasoulis A, Antoniades C, Stefanadis C. Fibrinogen and cardiovascular disease: genetics and biomarkers. Blood Rev. 2011;25(6):239–45.

Schneider DJ, Taatjes DJ, Howard DB, Sobel BE. Increased reactivity of platelets induced by fibrinogen independent of its binding to the IIb-IIIa surface glycoprotein: a potential contributor to cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33(1):261–6.

Hammer MR, John PN, Flynn MD, Bellingham AJ, Leslie RD. Glycated fibrinogen: a new index of short-term diabetic control. Ann Clin Biochem. 1989;26(Pt 1):58–62.

Brownlee M, Vlassara H, Cerami A. Nonenzymatic glycosylation reduces the susceptibility of fibrin to degradation by plasmin. Diabetes. 1983;32(7):680–4.

Bobbink IW, Tekelenburg WL, Sixma JJ, de Boer HC, Banga JD, de Groot PG. Glycated proteins modulate tissue-plasminogen activator-catalyzed plasminogen activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;240(3):595–601.

Lutjens A, Jonkhoff-Slok TW, Sandkuijl C, vd Veen EA, vd Meer J. Polymerisation and crosslinking of fibrin monomers in diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1988;31(11):825–30.

Grant PJ. Diabetes mellitus as a prothrombotic condition. J Intern Med. 2007;262(2):157–72.

Lee AJ, Lowe GD, Woodward M, Tunstall-Pedoe H. Fibrinogen in relation to personal history of prevalent hypertension, diabetes, stroke, intermittent claudication, coronary heart disease, and family history: the Scottish Heart Health Study. Br Heart J. 1993;69(4):338–42.

Qizilbash N, Jones L, Warlow C, Mann J. Fibrinogen and lipid concentrations as risk factors for transient ischaemic attacks and minor ischaemic strokes. BMJ. 1991;303(6803):605–9.

Wilhelmsen L, Svardsudd K, Korsan-Bengtsen K, Larsson B, Welin L, Tibblin G. Fibrinogen as a risk factor for stroke and myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1984;311(8):501–5.

Danesh J, Lewington S, Thompson SG, Lowe GD, Collins R, Kostis JB, Wilson AC, Folsom AR, Wu K, Benderly M, et al. Plasma fibrinogen level and the risk of major cardiovascular diseases and nonvascular mortality: an individual participant meta-analysis. JAMA. 2005;294(14):1799–809.

Kofoed SC, Wittrup HH, Sillesen H, Nordestgaard BG. Fibrinogen predicts ischaemic stroke and advanced atherosclerosis but not echolucent, rupture-prone carotid plaques: the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Eur Heart J. 2003;24(6):567–76.

del Zoppo GJ, Levy DE, Wasiewski WW, Pancioli AM, Demchuk AM, Trammel J, Demaerschalk BM, Kaste M, Albers GW, Ringelstein EB. Hyperfibrinogenemia and functional outcome from acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2009;40(5):1687–91.

Ogawa H, Nakayama M, Morimoto T, Uemura S, Kanauchi M, Doi N, Jinnouchi H, Sugiyama S, Saito Y, Japanese Primary Prevention of Atherosclerosis With Aspirin for Diabetes Trial I. Low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of atherosclerotic events in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300(18):2134–41.

Belch J, MacCuish A, Campbell I, Cobbe S, Taylor R, Prescott R, Lee R, Bancroft J, MacEwan S, Shepherd J, et al. The prevention of progression of arterial disease and diabetes (POPADAD) trial: factorial randomised placebo controlled trial of aspirin and antioxidants in patients with diabetes and asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease. BMJ. 2008;337:a1840.

Hall HM, Banerjee S, McGuire DK. Variability of clopidogrel response in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2011;8(4):245–53.

Paul R, Banerjee AK, Guha S, Chaudhuri U, Ghosh S, Mondal J, Bandyopadhyay R. Study of platelet aggregation in acute coronary syndrome with special reference to metabolic syndrome. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2013;3(2):117–21.

Hao Z, Liu M, Counsell C, Wardlaw JM, Lin S, Zhao X. Fibrinogen depleting agents for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;3:CD000091.

Aono Y, Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Hara A, Kondo T, Obara T, Metoki H, Inoue R, Asayama K, Shintani Y, et al. Plasma fibrinogen, ambulatory blood pressure, and silent cerebrovascular lesions: the Ohasama study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(4):963–8.

Neumann-Haefelin T, Hoelig S, Berkefeld J, Fiehler J, Gass A, Humpich M, Kastrup A, Kucinski T, Lecei O, Liebeskind DS, et al. Leukoaraiosis is a risk factor for symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage after thrombolysis for acute stroke. Stroke. 2006;37(10):2463–6.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This work was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2014R1A1A1008249, J.S.L). The funding body had no role in the design of the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and in writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due for they are personal data, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

SJL contributed to analysis and interpretation of data, preparation and review of the manuscript. JMH contributed to patient data acquisition and review of the manuscript. SEL contributed to patient data acquisition of the manuscript. DRK contributed to statistical analysis of the data. BO contributed to analysis and interpretation of data and review of the manuscript. AMD contributed to analysis and interpretation of data and review of the manuscript. JSL contributed to analysis and interpretation of data, preparation and review of the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

As this was a retrospective study, consent for publication was waivered.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ajou University Hospital. As this was a retrospective study, consent to participate was waivered.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

A dot plot of standardized mean differences before and after propensity score matching in (A) DM population and (B) non-DM population. (TIFF 261 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S1.

Comparison before and after propensity score matching in patients with acute ischemic stroke admitted within 72 h, but without diabetes. Table S2. A logistic regression model for END after propensity score matching in patients without diabetes mellitus admitted within 72 h of acute ischemic stroke. (DOCX 25 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, SJ., Hong, J.M., Lee, S.E. et al. Association of fibrinogen level with early neurological deterioration among acute ischemic stroke patients with diabetes. BMC Neurol 17, 101 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-017-0865-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-017-0865-7