Abstract

Background

Hearing loss is highly prevalent and associated with reduced well-being in older adults. But little is known about the role of social factors in the association of hearing difficulty and its health consequences. This study aims to examine the association between self-reported hearing loss and health-related quality of life (HRQoL, consisted of physical and mental component summary, PCS and MCS), and to investigate whether social engagement mediates this association.

Method

Data on 4035 older adults aged 60 years or above from a cross-sectional nationally representative database in China were obtained to address this study. HRQoL was measured by the Short Form 12 Health Survey (SF-12). Hearing loss was defined by a dichotomized measure of self-reported hearing difficulty, which has been proved to be sensitive and displayed moderate associations with audiometric assessment in elderly population. Social engagement was measured by the Index of Social Engagement Scale. Bootstrap test was applied to test for the significance of the mediating role of social engagement.

Results

Self-reported hearing loss was found negatively associated with HRQoL in older adults, and hearing loss was much more related to reduced mental well-being. Social engagement played a partial mediating role in the association of hearing loss and HRQoL. Social engagement account for 4.14% of the variance in the change of PCS scores and 13.72% for MCS, respectively.

Conclusion

The study lends support to the hypothesis that hearing loss is associated with aging well beings, and the use of hearing aid or proper social engagement intervention may improve the quality of life among the elderly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL), an important concept to describe subjective well-being, is defined as the quality of life that directly or indirectly related to health [1]. It is a comprehensive and multidimensional construct that reflects an individual’s physical health, psychological state, social relationships and emotional well-being [2, 3]. Impaired HRQoL predicts mortality and demands of health service utilization [4, 5]. A study of using SF-12 scale to measure the HRQoL of older adults aged 65 or above and found that individuals with lower physical component summary (PCS) or mental component summary (MCS) scores were in higher risk of death and hospitalization [6]. Personal and environmental contextual factors can impact individuals’ health-related quality of life. Evidences from China suggest that socio-demographic factors (e.g. marital quality and living arrangement), socio-economic status (SES), lifestyle, chronic health conditions and the place of residence may account for the decline in HRQoL [7,8,9,10,11,12]. Sensory impairment, such as cataract disease and age-related hearing loss, is negatively associated with the elderly HRQoL [13, 14].

Hearing loss, ranked as the third most prevalent chronic medical condition in older adults, only exceeded by arthritis and hypertension [15]. Approximately 11% older adults aged 60 or above in China were diagnosed with hearing impairment in China [16]. Audiometric hearing loss is associated with impaired quality of life [17, 18]. Auditory dysfunction can impair individual’s function of information exchange and have adverse impact on individual’s emotional, behavioral and cognitive reactions [19]. Communication breakdown and social isolation accompanied by hearing loss in older adulthood [20, 21] may result in anxiety, depression, impaired social interactions, physical dysfunctions [22, 23]. In addition, adults with hearing loss were more likely to be associated with lower individual and household socio-economic status [24, 25], making them more exposed to adverse life events, unhealthy lifestyles and stress perceptions, which exceed their coping capacity [26], resulting in higher risk for physical and psychological stresses [27,28,29]. Therefore, these stressors interact with neuronal plasticity and the immune system, which could contribute to the decline in health-related quality of life [30, 31]. Moreover, since hearing loss and financial strain can be treated as chronic stressors to individual’s wellbeing [32], older adults suffering with hearing loss as well as living in low-income households may face with dual risks of adverse health outcomes.

According to Social network theory, social network may influence health by promoting social participation and social engagement [33]. Social engagement, as interactions with potential ties in real life, provides individuals with a coherent and consistent sense of role identity, companionship and sociability as well. As a reasonable measure of social connectedness, engagement in social activities may foster communication, increase social capital and aide in increasing social resources and material goods, in order to cope with the negative impacts that physical stressor exerts on well beings [34]. Persons with age-related hearing loss may have challenges communicating verbally in the presence of background noise [35]. As a consequence, social gatherings or participation in social activities may become difficult and less enjoyed. Although previous studies have shown that social isolation may be one of the hypothesized mechanisms for the association between hearing loss and health consequences [36], empirical evidences on social engagement as a partial mediator in the relationship between hearing loss and HRQoL are very limited.

In a society with a large number of poor aging population, it is of great significance to identify the impacts of age-related hearing deficits on health and to find out the potential social intervention approaches. Although there are growing evidences on the association between hearing loss and quality of life in western countries, few studies have been done on this issue in China [37], particularly among poor individuals who may suffer from accumulated deficits of physical and economic difficulties. Moreover, most of studies in China were conducted with clinical series or other convenience sample [37,38,39], which may result in sample bias or overestimate the impact of hearing loss on health. In this study, we used a nationally representative and population-based data from Survey on the Aged Population of Low-income Families in Urban/Rural China (2018), aiming to examine 1) the association between hearing loss (HL) and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among Chinese older adults aged 60 or above and living in a low-income household, and 2) the mediating role of social engagement in the relation of HL and HRQoL. The findings of this study will fill gaps on this issue in mainland China and contribute to the existing studies by addressing some limitations.

Methods

Participants

We obtained data from Survey on the Aged Population of Low-income Families in Urban/Rural China (2018), which was conducted from July 1 to September 31, 2018. The survey was approved and sponsored by the Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People’s Republic of China and carried out by the Institute of Social Science Survey, Peking University. The purpose of this survey was to investigate the well beings, family conditions, physical and psychological health status, social support, social networks, and health service utilizations of older adults aged 60 years or above who live in low-income households. The results of this survey were considered as the scientific basis for the formulation and implementation of low-income household policies for national and local governments in China [40].

Multistage, stratified and random-cluster sampling was used in this survey, which covered 155 counties (districts) and 1800 communities (villages) in 28 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities in China. Low-income family in this survey was defined as family whose annual household income per capita is below 1.5 times the local minimum living standard. Every three or four targeted households were matched with one geographically nearby general household as the control group. Home visits were conducted by trained investigators. All participants consented to participate in the survey, and the initial sample consisted of 6042 participants. In this study, we restricted our analysis to 4035 older adults living in low-income households with completed information on the questions we are concerned.

Measures

The outcome variable of this study was the summary score of individual’s health-related quality of life. HRQoL was measured by the Chinese version 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12), which has been tested with satisfactory reliability and validity in measuring health status of Chinese elderly population [41]. SF-12 was a HRQoL instrument based on the 36-item Short-Form Health survey (SF-36) [42, 43]. HRQoL measured by SF-12 was consisted of physical health and mental health component summary scores (PCS and MCS), reflecting individual’s physical and mental health status respectively. PCS an MCS were scored with a mean of 50 and a SD of 10 in the general population [43]. The higher the score, the better health and functional status.

The independent variable in this study was whether an individual had a self-reported hearing loss. Participants were asked the following question to check their hearing status (with hearing aid): “Do you have any difficulty with your hearing? The answers were coded as: 1. very difficult; 2. have some difficulties in hearing; 3. can hear clearly.” In this study, hearing loss was defined by a response of self-perceived hearing difficulties. Self-reported hearing loss, being regarded as a subjective assessment of hearing functions limitation, was treated as a binary variable (yes vs. no) in this study. Self-assessed hearing loss among elderly population reflects hearing disability. The validation of self-reported hearing loss in health research have been examined in prior study, and the results demonstrated that the single question for hearing loss yielded reasonable sensitivity and was minimally affected by age and gender, which could be recommended for use in assessing the magnitude of health burden caused by age-related sensory impairment [44, 45].

Social engagement was selected as a putative mediator variable based on theoretical assumptions from the literature. In this study, social engagement is assessed by the Index of Social Engagement (ISE), which was composed of six dichotomous items: (a) at ease interacting with others, (b) at ease doing planned or structured activities, (c) at ease doing self-initiated activities, (d) establish own goals, (e) pursues involvement in life of facility, and (f) accepts invitations into most group activities. The ISE scores ranged from 0 (lowest) to 6 (highest), and the scale demonstrated internal consistency and good reliability [46]. A cutoff point 2 was applied, and poor social engagement was referred to ISE scores below 2 [47].

Covariates in this study included sociodemographic, socio-economic, health behavior and health conditions characteristics, which were potentially associated with HRQoL according to previous studies [7, 12]. These variables specifically embraced age (continuous), sex (male vs. female), marital status (with spouse vs. without spouse), residence (urban vs. rural), education (illiterate vs. literate), household income (logarithm (X + 1), continuous), current employment status (yes vs. no), smoking (non-smoker, ex-smoker, vs. current-smoker), drinking (non-drinker, ex-drinker vs. current-drinker), and number of chronic disease (0, 1, 2, vs. 3 or above).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis of the mean and distribution of the study variables were reported for the study population. Difference between the study variables and hearing status were assessed using Chi-square test for categorical variables (sex, marital status, residence, employment status, smoking, drinking and number of chronic diseases) and a t test for continuous variables (age, HRQoL, social engagement). A Linear regression was applied to identify the association of the presence of hearing loss with PCS and MCS HRQoL. Nonparametric bias-corrected case resampling bootstrap method, which was valid in testing a single-mediator model [48], was employed to estimate the indirect effect of social engagement. Observations in which data were missing for one or more variables of each model were not included in the estimations. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The software STATA 13.0(Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, United States) for Windows was utilized for statistical analysis.

Results

Table 1 presents the sample characteristics. Overall, the mean age of the sample was 69.26 years (SD = 6.56), with 2230 males (55.71%) and 2460 older adults (61.61%) lived without spouse. In the sample, 2508 (62.65%), 3043(76.02%) and 1061(26.51%) individuals were in urban area, literate and employed after retirement, respectively. 2305(57.58%) adults were non-smoker and 2449(61.18%) did not drink. Besides, there were 1859(46.44%) cases had more than 3 chronic diseases, and the average household income per capita was 9600 RMB (SD = 10,141.16).

The PCS scores of the sample was 42.10(SD = 7.37) and 41.11(SD = 11.47) for MCS scores, respectively. One thousand five hundred twenty-four participants (38.07%) were self-reported with hearing loss and the mean scores of ISE was 3.94(SD = 1.95).

Table 1 also presents the bivariate analysis by hearing loss status. Older adults with hearing loss had lower scores of PCS and MCS, with 40.91 (SD = 0.18) for PCS and 39.41 (SD = 0.28) for MCS among adults with HL compared with 42.83 (SD = 0.15) for PCS and 42.16(SD = 0.23) for MCS among those without HL, respectively. Furthermore, individuals with HL reported lower scores of social engagement, with average score of 3.69(SD = 0.05), while that of non-HL group was 4.10 (SD = 0.04).

The multivariate association between HL and HRQoL (PCS and MCS), as well as the mediating role of social engagement in this relationship are shown in Table 2. Model 1 shows that there was a significant correlation between older adults with self-perceived hearing loss and low scores on PCS and MCS of HRQoL (p < 0.001). Compared with those without hearing loss, older adults with hearing loss had 1.92-point lower PCS scores and 2.76-point lower MCS scores, respectively. After adjusting for socio-demographic, SES and health conditions in Model 2, the association between hearing loss and health-related quality of life (both PCS and MCS) remained significant (p < 0.001). Age, sex, education, household income per capita and the number of chronic diseases were associated with HRQoL. Female and illiteracy had higher risk in lower PCS and MCS. As household income per capita increased, older adults were more likely to report better HRQoL. Moreover, with the number of chronic diseases increasing, the HRQoL of individuas tend to be lower.

Two OLS regressions were used to identify the mediating role of social engagement in the association between hearing loss and HRQoL. In Model 3, we used social engagement as a dependent variable and found that hearing loss was negatively associated with social engagement. In Model 4, after adjusting for social engagement and other covariates, hearing loss remained significantly associated with lower levels of PCS and MCS. Social engagement was related to HRQoL positively that social engagement raised in 1 score would be associated with 0.20-point increase in PCS and 1.14-points increase in MCS, indicating that social engagement played a meditating role in the linkage between HL and HRQoL.

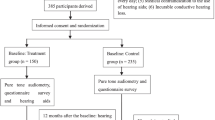

Figure 1 shows the coefficients for direct and indirect effects of self-reported hearing loss on PCS and MCS. Bia-corrected bootstrap procedure results further supported the mediation model. The indirect effects and 95% confidence intervals were − 0.049 [− 0.086,-0.012] for the partial mediating effects of social engagement on the association between hearing loss and PCS, demonstrating 4.14% of the variance in the change of PCS scores. Regarding to MCS, the indirect effects and 95% confidence intervals were − 0.277 [− 0.427,-0.128] for social engagement mediation, accounting for 13.27% of the variance in MCS scores. The bootstrap test result indicates statistically significant in both direct and indirect effect. Thus, social engagement mediates the linkage between hearing loss and HRQoL.

Discussion

In the context of aging society with increased risk of chronic illness and a national policy implementation of poverty elimination, physical stressor’s impacts on well beings of individuals facing dual burden of aging and poverty have become growingly important social and health concerns. In this study, we conceptualized hearing loss as a chronic physical stressor, and estimated whether it was associated with health-related quality of life in a sample of older adults with poverty, utilizing a nationally representative survey data from China. Based on social network theoretical framework, we further tested whether social engagement played a mediating role in the relationship between HL and HRQoL.

First, our findings indicate that hearing loss was negatively associated with health-related quality of life among older adults with poverty in China. The impact of hearing loss on PCS and MCS remained statistically significant after controlling socio-demographic, SES and health related conditions. Our results comported well with previous studies which were relied on both standardized audiometric measurement techniques and self-perceived hearing loss, that impairment of hearing acuities was correlated to decreased scores on quality of life [18, 49]. Acquired hearing loss in old age is initially gradual and unpreventable [50]. Unaddressed hearing loss may give rise to physical dysfunction and cognition decline [51], further leading to worse self-perceived physiological quality of life. In addition, a study with a sample of older Australians suggested that hearing loss was predictive of poorer performance in social functioning and role limitation [17]. Furthermore, hearing loss was associated with communication breakdown, which may require long-term management of behavioral changes, and may suffer from loss of images, relationships and personal identity, resulting in anxiety, depression and other adverse psychosocial consequences [52].

Second, our results suggest that social engagement played a mediating role in the association of hearing loss and PCS and MCS. This result indicated that older adult’s social interactions with friends and family mediated the linkage between hearing loss, a common sensory impairment in older adults, and their physiological or psychological health [53, 54]. Social engagement or social connectedness, which may increase emotional exchange and companionship, have consistently been associated with health-related quality of life [55, 56]. Social exchanges or interactions can reduce feelings of being isolated or abandoned [57, 58].

Older adults with hearing loss may have difficulties in communication due to decline in hearing sensitivity [21]. Hearing loss may restrict individuals with effectiveness in social communication and interpersonal interactions, which limits one’s ability in building positive relationship with family and friends. Inactive engagement with life may predict lower life satisfaction [59], reduced quality of life [60] and increased mortality [61].

Meanwhile, there are also some limitations in this study. Firstly, our survey relied on self-reported hearing impairment with hearing aids, and the validity of these complaints could not be confirmed. Estimates based on self-reported sensory deprivation may be inaccurate given the tendency of older individuals to deny or underestimate their hearing difficulty. Secondly, since the medical history for auditory function as well as the severity of hearing loss were not known, we are not able to measure the impact’s duration of hearing loss exerting on HRQoL. Additionally, the causal relationship between hearing loss and HRQoL could not be verified, in that the descriptive, correlational, cross-sectional design was employed in this study.

Despite these limitations, the strengths of this study are also evident, including not only using a nationally representative population-based data in China to evaluate the association between self-reported hearing loss and HRQoL in older adults with poverty, but also identifying the role of social engagement in mediating the relationship. To our best knowledge, this is the first study to analyze the association between hearing loss and quality of life, along with the role of social engagement as a mediator among the older adults with poverty in China. Findings of this study have public health implications for Chinese policy makers to consider the importance of audiologic rehabilitation programs and the role of social support or social engagement in promoting quality of life among the elderly.

Conclusion

Hearing loss is negatively associated with physical and mental health related quality of life among older adults with poverty in China. Social engagement mediates the linkage between hearing loss and HRQoL. In accordance with the stress-buffering and social network theory, hearing deficit, as a chronic physical stressor, can lead to poorer well-being, while social interactions could buffer (mediate) this relationship. Improvement in auditory function and social participation may contribute to promoting quality of life. Further studies are warranted to confirm our findings and to reveal the mechanism of hearing loss affecting quality of life, which will help identify the priority of hearing and health interventions for older adults.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to issues of individual privacy, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HRQoL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- PCS:

-

Physical component summary

- MCS:

-

Mental component summary

- SES:

-

Socio-economic status

- HL:

-

Hearing loss

- SF-12:

-

12-item Short Form Health Survey

- SF-36:

-

36-item Short-Form Health survey

- ISE:

-

Index of Social Engagement

References

Carr AJ, Gibson B, Robinson PG. Is quality of life determined by expectations or experience? BMJ. 2001;322(7296):1240–3.

Programme on Mental Health, World Health Organization annotated bibliography of the WHOQOL. Division of mental health and prevention of substance abuse. W H O; 1998. p. 1–32.

Schwimmer JB, Burwinkle TM, Varni JW. Health-related quality of life of severely obese children and adolescents. Jama. 2003;289(14):1813–9.

Dominick KL, Ahern FM, Gold CH, et al. Relationship of health-related quality of life to health care utilization and mortality among older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2003;14(6):499–508.

Tsai SY, Chi LY, Lee CH, et al. Health-related quality of life as a predictor of mortality among community-dwelling older persons. Eur J Epidemiol. 2007;22(1):19–26.

Mapes DL, Lopes AA, Satayathum S, et al. Health-related quality of life as a predictor of mortality and hospitalization: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Kidney Int. 2003;64(1):339–49.

Wang H, Kindig DA, Mullahy J. Variation in Chinese population health related quality of life: results from a EuroQol study in Beijing, China. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(1):119–32.

Wang R, Wu C, Zhao Y, et al. Health related quality of life measured by SF-36: a population-based study in Shanghai, China. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):292.

Sun XJ, Lucas H, Meng Q, et al. Associations between living arrangements and health-related quality of life of urban elderly people: a study from China. Qual Life Res. 2011;20(3):359–69.

Sun S, Chen JY, Johannesson M, et al. Regional differences in health status in China: population health-related quality of life results from the National Health Services Survey 2008. Health Place. 2011;17(2):671–80.

Xu J, Qiu J, Chen J, et al. Lifestyle and health-related quality of life: A cross-sectional study among civil servants in China. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):330.

Dai H, Jia G, Liu K. Health-related quality of life and related factors among elderly people in Jinzhou, China: a cross-sectional study. Public Health. 2015;129(6):667–73.

Liang Y, Guo M. Utilization of health services and health-related quality of life research of rural-to-urban migrants in China: a cross-sectional analysis. Soc Indic Res. 2015;120(1):277–95.

Fischer ME, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BE, et al. Multiple sensory impairment and quality of life. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2009;16(6):346–53.

Prevention C o D C a. Summary health statistics: national health interview survey.2017.3rd. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/shs/tables.htm. Accessed 5 Nov 2019.

Yu L, Sun X, Wei Z, et al. A study on the status quo of aged population with hearing loss in China. Chin Sci J Hearing Speech Rehab. 2008;3:63–5.

Chia EM, Wang JJ, Rochtchina E, et al. Hearing impairment and health-related quality of life: the Blue Mountains Hearing Study. Ear Hearing. 2007;28(2):187–95.

Dalton DS, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BE, et al. The impact of hearing loss on quality of life in older adults. Gerontologist. 2003;43(5):661–8.

Ciorba A, Bianchini C, Pelucchi S, et al. The impact of hearing loss on the quality of life of elderly adults. Clin Intervent Aging. 2012;7:159.

Heine C, Browning C. Communication and psychosocial consequences of sensory loss in older adults: overview and rehabilitation directions. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24(15):763–73.

Mick P, Kawachi I, Lin FR. The association between hearing loss and social isolation in older adults. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;150(3):378–84.

Pronk M, Deeg DJ, Smits C, et al. Hearing loss in older persons: Does the rate of decline affect psychosocial health? J Aging Health. 2014;26(5):703–23.

Gopinath B, Schneider J, McMahon CM, et al. Severity of age-related hearing loss is associated with impaired activities of daily living. Age Ageing. 2012;41(2):195–200.

He P, Luo Y, Hu X, et al. Association of socioeconomic status with hearing loss in Chinese working-aged adults: a population-based study. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0195227.

Helvik AS, Krokstad S, Tambs K. Socioeconomic inequalities in hearing loss in a healthy population sample: The HUNT Study. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(8):1376–8.

Adler NE, Boyce T, Chesney MA, et al. Socioeconomic status and health: the challenge of the gradient. Am Psychol. 1994;49(1):15–24.

Santiago CD, Wadsworth ME, Stump J. Socioeconomic status, neighborhood disadvantage, and poverty-related stress: prospective effects on psychological syndromes among diverse low-income families. J Econ Psychol. 2011;32(2):218–30.

Cohen S, Doyle WJ, Baum A. Socioeconomic status is associated with stress hormones. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(3):414–20.

Aneshensel CS. Social stress: Theory and research. Ann Rev Soc. 1992;18(1):15–38.

Barlow DH. Principles and practice of stress management. New York: Academic; 2007.

Canlon B, Theorell T, Hasson D. Associations between stress and hearing problems in humans. Hear Res. 2013;295:9–15.

West JS. Hearing impairment, social support, and depressive symptoms among US adults: a test of the stress process paradigm. Soc Sci Med. 2017;192:94–101.

Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, et al. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium ☆. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(6):843–57.

Pillemer SC, Holtzer R. The differential relationships of dimensions of perceived social support with cognitive function among older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2015;20(7):1–9.

Gopinath B, Hickson L, Schneider J, et al. Hearing-impaired adults are at increased risk of experiencing emotional distress and social engagement restrictions five years later. Age Ageing. 2012;41(5):618–23.

Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC. Social isolation and health, with an emphasis on underlying mechanisms. Perspect Biol Med. 2003;46(3x):S39–52.

Wong LL, Cheng LK. Quality of life in older Chinese-speaking adults with hearing impairment. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(8):655–64.

安奇志,马婧,姜鸿, et al. 老年性听力障碍病人的生活质量调查. 护理研究. 2016; 30(14):1749–1751.

Liu H, Zhang H, Liu S, et al. International outcome inventory for hearing aids (IOI-HA): Results from the Chinese version. Int J Audiol. 2011;50(10):673–8.

Wang JX, Tang J. Studies on policy of social support system of low-income families in urban/rural China. Beijing: China Society Press; 2017.

Shou J, Ren L, Wang H, et al. Reliability and validity of 12-item short-form health survey (SF-12) for the health status of Chinese community elderly population in Xujiahui district of Shanghai. Aging Clin Experiment Res. 2016;28(2):339–46.

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33.

Jenkinson C, Layte R, Jenkinson D, et al. A shorter form health survey: can the SF-12 replicate results from the SF-36 in longitudinal studies? J Public Health Med. 1997;19(2):179–86.

Kiely KM, Gopinath B, Mitchell P, et al. Evaluating a dichotomized measure of self-reported hearing loss against gold standard audiometry: prevalence estimates and age bias in a pooled national data set. J Aging Health. 2012;24(3):439–58.

Sindhusake D, Mitchell P, Smith W, et al. Validation of self-reported hearing loss. The Blue Mountains hearing study. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30(6):1371–8.

Sgadari A, Morris JN, Fries BE, et al. Efforts to establish the reliability of the Resident Assessment Instrument. Age Ageing. 1997;26(suppl_2):27–30.

Resnick HE, Fries BE, Verbrugge LM. Windows to their world: the effect of sensory impairments on social engagement and activity time in nursing home residents. J Gerontol. 1997;52(3):S135–44.

Taylor AB, Mackinnon DP. Four applications of permutation methods to testing a single-mediator model. Behav Res Methods. 2012;44(3):806–44.

Lopez D, McCaul KA, Hankey GJ, et al. Falls, injuries from falls, health related quality of life and mortality in older adults with vision and hearing impairment—is there a gender difference? Maturitas. 2011;69(4):359–64.

Gates GA, Mills JH. Presbycusis. Lancet. 2005;366(9491):1111–20.

Lin FR, Yaffe K, Xia J, et al. Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(4):293–9.

Carlsson PI, Hall M, Lind KJ, et al. Quality of life, psychosocial consequences, and audiological rehabilitation after sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Int J Audiol. 2011;50(2):139–44.

Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98(2):310–57. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310.

Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer publishing company; 1984.

Sánchez J, Muller V, Chan F, et al. Personal and environmental contextual factors as mediators between functional disability and quality of life in adults with serious mental illness: a cross-sectional analysis. Qual Life Res. 2006;28(2):441–50.

Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health. 2001;78(3):458–67.

Newsom JT, Rook KS, Nishishiba M, et al. Understanding the relative importance of positive and negative social exchanges: examining specific domains and appraisals. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60(6):P304–12.

Glass TA, De Leon CFM, Bassuk SS, et al. Social engagement and depressive symptoms in late life: longitudinal findings. J Aging Health. 2006;18(4):604–28.

Jang Y, Mortimer JA, Haley WE, et al. The role of social engagement in life satisfaction: its significance among older individuals with disease and disability. J Appl Gerontol. 2004;23(3):266–78.

Horowitz BP, Vanner E. Relationships among active engagement in life activities and quality of life for assisted-living residents. J Hous Elder. 2010;24(2):130–50.

Thomas PA. Trajectories of social engagement and mortality in late life. J Aging Health. 2011;52(4):430–43.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to all participants of the Survey on the Aged Population of Low-income Families in China.

Author details

1 Guanghua School of Management, Peking University, No.5, Yiheyuan Road, Haidian District, Beijing, P.R. China, 100,871; 2 Institute of Strategy Research, Peking University, No.5, Yiheyuan Road, Haidian District, Beijing, P.R. China, 100,871;3 School of Public Administration and Policy, Renmin University of China, No. 59, Zhongguancun Street, Haidian District, Beijing 100,872, P.R. China;

Funding

China National Social Science Youth Grant (No.19CRK009) support the design of the study, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship. Authors JG, HH contributed to conceptualization and design of the study, analysis, and the interpretation of data. JG drafted the manuscript. HH supervised and collected the data. LY contributed for manuscript editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

A written informed consent to participate the interview was presented by investigators at the beginning of face-to-face interviews. Eligible participants received written information mail detailing the survey on the aged population prior to a home visit. The interview would be continued if the participants agreed with the written informed consent mail. The survey was approved by the Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People’s Republic of China and carried out by the Institute of Social Science Survey, Peking University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, J., Hu, H. & Yao, L. The role of social engagement in the association of self-reported hearing loss and health-related quality of life. BMC Geriatr 20, 182 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01581-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01581-0