Abstract

Background

Modern high-throughput genomic technologies represent a comprehensive hallmark of molecular changes in pan-cancer studies. Although different cancer gene signatures have been revealed, the mechanism of tumourigenesis has yet to be completely understood. Pathways and networks are important tools to explain the role of genes in functional genomic studies. However, few methods consider the functional non-equal roles of genes in pathways and the complex gene-gene interactions in a network.

Results

We present a novel method in pan-cancer analysis that identifies de-regulated genes with a functional role by integrating pathway and network data.

A pan-cancer analysis of 7158 tumour/normal samples from 16 cancer types identified 895 genes with a central role in pathways and de-regulated in cancer.

Comparing our approach with 15 current tools that identify cancer driver genes, we found that 35.6% of the 895 genes identified by our method have been found as cancer driver genes with at least 2/15 tools.

Finally, we applied a machine learning algorithm on 16 independent GEO cancer datasets to validate the diagnostic role of cancer driver genes for each cancer. We obtained a list of the top-ten cancer driver genes for each cancer considered in this study.

Conclusions

Our analysis 1) confirmed that there are several known cancer driver genes in common among different types of cancer, 2) highlighted that cancer driver genes are able to regulate crucial pathways.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Although an increasing number of disease biomarkers have been identified through high-throughput data, their reproducibility and overlap are poor. This poor reproducibility is possibly due to the fact that individual biomarkers are often selected without considering their metabolic role in terms of their cellular function.

Many studies have thus hypothesized that a more reproducible method may be to analyze gene expression profiles over functional pathways that express different cellular functions (e.g. i.e. cell cycle, apoptosis, proliferation) [1, 2]. Databases such as Gene Ontology [3], Reactome [4], the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) [5], and Biocarta [6] describe the different cellular functions (pathways) as exploited by a list of genes. However, this functional pathway representation attributes the same functional significance to each gene in the list without considering the impact of gene interactions in performing this function.

What kinds of connections are there among genes in functional pathways? Some tools, such as GeneMania [7], describe the biological relationships among the cellular components, i.e. physical interactions, genetic interactions, shared-protein functional domains, or the co-localization of molecules. These connections identify those gene regulatory networks that play crucial roles in many key biological processes, such as cell differentiation, metabolism, cell cycles, and signal transduction.

Establishing the role of a gene within pathways and networks facilitates a multi-layered description of its functional role in both physiological and pathological conditions, and enables the network drivers to be identified [8]. When a pathological process is ongoing, the dynamics of pathways and networks are altered. Thus, the integration of networks with pathways can help to describe these dynamics and to identify the key network drivers with a functional role in the onset and progression of a disease. A perturbation of the expression level of a key network driver should have a larger impact on a pathway function compared to a non-key network driver, and on the network itself because of the connections between this gene and its downstream effectors.

Only a few methods have defined indexes that measure how central the role of a gene is in a functional pathway in terms of biological networks [9, 10]. These indexes could help to identify genes with key biological relationships within a functional pathway [9, 10], and to identify key network drivers. For example, in a graph analysis of a biological network, the degree centrality [9, 10] quantifies the number of interactions (edges) connected to a gene (node).

Several studies have shown that the absence of mutations in genes with a high degree centrality is vital for organism survival [11]. Indeed, the degree centrality can identify genes with a key role in the functional pathway [7, 8]. Degree centrality has been used by Fang [9] in an approach called “Gene Association Network-based Pathway Analysis” (GANPA) in order to assign a weight for each gene within pathways. The assignment of weights for each gene in a pathway is based on to its relative association with genes inside and outside the pathway in a functional association network, based on protein-protein interactions, co-annotations, and co-expression. GANPA has also been proposed as a tool for the Functional Category Score (FCS), where a weighted gene is integrated with an expression change value to detect pathways with significant expression changes.

Dong et al. [10] adopted a similar approach to GANPA and developed a new tool for Over-Representation Analysis (ORA) called "functional Link Enrichment of Gene Ontology or gene sets" (LEGO). The main differences between ORA and FCS are: 1) FCS uses profiles of gene expression values, whereas ORA only considers the genes of interest, 2) the statistical test for FCS is based on the gene set, whereas ORA uses the interesting genes [10]. The aim of both GANPA and LEGO is to identify the relevant pathways of a particular condition.

The cancer research community refers to ‘cancer driver’ genes as genes whose perturbation (in the expression levels or in the sequence) confers a selective advantage to tumour growth [12]. Cancer driver genes need to be distinguished from ‘passenger’ genes, i.e. those genes whose mutation does not give any fitness advantage to the tumour [13]. In cancer, driver genes are those that accumulate mutations, or those that are differentially expressed in tumours vs normal samples (differentially expressed genes) [14, 15]. Both cases could lead to cancer initiation and development. Several studies have demonstrated that driver genes and driver mutations tend to accumulate in a limited number of cellular pathways, in which these driver genes have a central role [16,17,18].

Here, we propose an application of the GANPA/LEGO approach for the integrative analysis of multi-networks with multi-pathways with a novel purpose with respect to previous studies [9, 10]. Our aim was to reveal those network drivers that control key biological processes in a pan-cancer study.

In our approach, the GANPA/LEGO method was also extended by integrating biological multiplex networks. We thus defined key cancer network drivers as those cancer drivers that are simultaneously highly connected in at least two interaction types.

From an analysis of 7158 tumour/normal samples of 16 cancer types, we identified 895 differentially expressed genes with a central role in pathways and networks. These genes are deregulated in cancer with a reduced False Discovery Rate (FDR) compared to that obtained by commonly used differential expression analyses. For each cancer type, we also obtained a list of the top 10 cancer drivers able to classify normal versus tumour samples, with a high performance in independent datasets.

Methods

The computational approach

We used a modified version of the GANPA/LEGO algorithm [9, 10] to compute: 1) the degree centrality of genes inside networks (d N ), and 2) the degree centrality of genes inside pathways (d P ), as follows.

In the first step, given the gene i within the network N with m genes, we calculated degree centrality di N as the number of neighbor genes belonging to N to which the gene i is directly linked.

In the second step, given gene i within pathway P with k genes, we then calculated degree centrality di P considering only network interactions among gene i and the other genes in the networks belonging to pathway P. In this step by integrating the information of the network N within pathway P, we obtained a selection of interacting genes according to the network N.

Then, we computed degree centrality expected di E by assuming equal probability for the existence of edges between nodes (di N /m = di E /k, [9, 10]). Thus,

We defined a gene as a ‘network driver’ in the pathway P, when, in at least two networks involving gene i, its di P , normalized to the size of the pathway (k), is higher than di E , according to eq. 1:

The hypothesis is that if one gene is functionally linked (according to the functional networks) with more genes in the pathway than expected, its role is functionally central in that pathway.

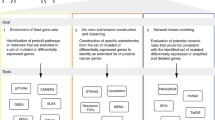

Figure 1 shows the proposed procedure. The code is made available in the StarBioTrek package (http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/StarBioTrek.html).

The computational approach. The first step involves a network N (e.g. physical interaction) of size m and for each gene, i in N the algorithm calculates its degree centrality, DC (di N ). The second step involves a list of functional pathways (e.g. pathway P) and for each gene i, the DC (di p ) is calculated using the information on interacting genes from N. For the assumption of equal probability for existing edges between nodes, the algorithm calculates the expected DC of gene i in the pathway P. If the DC observed for the gene i (di p ) is higher than expected (di p_expected ), i could be a potential driver in the pathway P

Pathways and networks

Using the KEGGREST [19] and StarBioTrek [20] packages, we downloaded 307 pathways from the KEGG database [5], which includes lists of genes grouped by functional role (e.g. cell cycle, apoptosis, proliferation). Different types of validated gene-gene or protein-protein networks, which include physical interaction, genetic interaction, shared protein domains, co-localization, and functional reaction interactions, were downloaded using SpidermiR [21].

Differentially expressed genes

We applied our approach to cancer datasets obtained from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [22]. We used the Illumina HiSeq RNAseqv2 of 7158 tumour/normal samples from 16 cancer types (see Table 1). We used the TCGAbiolinks package [23] and the TCGA Workflow [24] to download and process Level 3 TCGA gene expression data with platform RNAseqv2. The processing steps that were applied involve within-lane normalization procedures to adjust for GC-content effects on read counts and between-lane normalization procedures to adjust for distributional differences between lanes using the EDASeq package [25] as reported in [23, 24].

For each cancer type, we performed a differential expression analysis (DEA) between two classes, normal vs tumoural, using TCGAbiolinks [23, 24], identifying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (logFC > 1, logFC < −1, FDR < 0.01) [23, 24].

Application of our computational approach to the identification of cancer-specific drivers

We applied the computational approach described above to the study of key network drivers in cancer. For each cancer type, we computed d N , d P , and di E of DEGs and selected cancer-specific network drivers accordance with (Eq. 1), which are DEGs with high degree centrality in networks with a functional role in the onset and progression of cancer.

In order to visualize the results obtained for each network and all possible combinations between different networks, we constructed a Venn diagram [26].

For each cancer type, we computed the number of cancer driver DEGs shared with all network drivers. We compared FDR, which measures the probability that a gene is a false positive DEG, between DEGs obtained by DEA and our cancer-specific network driver DEGs obtained in accordance with (Eq. 1) for each cancer type.

Benchmarking validation

To verify our method, we compared our results and those obtained by other well-validated computational methods used to identify cancer driver genes, such as ActiveDriver [27], Dendrix [28], MDPFinder [29], Simon [30], NetBox [31], OncodriveFM [32], MutsigCV [33], MeMo [34], CoMDP [35], DawnRank [36], DriverNet [37], e-Driver [38], iPAC [39], MSEA [40], and OncodriveCLUST [41].

We applied DriverDB [42] to obtain results from all these algorithms and the cancer datasets considered by our computation approach.

In silico validation

In silico validation analysis using our cancer drivers was performed using independent datasets. For each cancer, gene expression data were obtained from the GEO database (see Table 2). GEO datasets were analyzed using MoonlightR [43]. The processing steps included a normalization procedure (quantile analysis) and a log transformation using GEO2R as performed in [44].

We developed a Random Forest (RF) classification model using R-package [45]. The model was used to classify the considered tumour versus normal samples using the gene expression levels of our cancer driver genes.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves and Area Under Curve (AUC) were estimated for each gene belonging to the cancer-specific driver DEGs by a cross-validation method (k-fold cross-validation, k = 10). We adopted the following parameters: mtry (number of variables randomly sampled as candidates at each split) = sqrt(p), p being the number of variables in the matrix of data; ntree (number of trees grown) = 500. We then created a list of the top ten cancer drivers with the best AUC performance for each cancer type.

Results

Network driver genes

We applied our method for each functional network considered for 307 KEGG functional pathways (Fig. 2). The network that includes genes with genetic interaction found the lowest number of potential gene drivers, (50 genes). On the other hand, the network that includes proteins with shared protein domains found the highest number of potential driver genes, (1922 genes). Furthermore, our algorithm found 468 potential genes drivers for co-localization, 1402 for physical interaction, and 974 for functional reaction interactions.

For each pathway (x axis), the following results are shown: the number of genes (y axis) in the original KEGG data (blue line), genes with a direct interaction (red line, a co-localization, CO; b shared protein domain, SHP; c genetic interaction, GI; d physical interaction, PI; and e functional reaction interactions, FRI) and the results of our computational method (green line, potential driver genes)

Additional file 1 shows the potential driver genes for each pathway and network.

To focus on the network driver genes, we constructed a Venn diagram in which we plotted the list of potential gene drivers (y axis) and selected networks/intersecting networks (x axis) (Fig. 3). The results obtained by our method applied to the different networks highlighted 1322 common genes in at least two networks (Additional file 2).

As shown in Fig. 3 we obtained 102 network driver genes that were present in at least four networks, and there were no genes in any of the five networks considered.

Cancer-specific driver DEGs

For each cancer type, with our approach we found the number of DEGs obtained by DEA from TCGA data (Table 3). For each cancer type we identified from all the DEGs the number of cancer-specific driver genes (cancer drivers with high degree centrality) (Table 3). We found 895 cancer-specific driver DEGs, in common among network drivers (1322) and DEGs (Table 3), i.e. 67% of all network driver genes. Additional file 3 shows the list of 895 genes.

It should be noted that our computational approach found cancer driver DEGs with lower FDRs than that obtained by only DEA (Fig. 4).

In order to highlight the number of cancer driver DEGs with high degree centrality in common between two different cancer types, we generated the heat map shown in Fig. 5.

Bladder urothelial carcinoma has 134 key cancer driver DEGs in common with lung squamous cell carcinoma, 196, 151 and 140 in common between lung squamous cell carcinoma and uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma, lung adenocarcinoma and uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma, and breast invasive carcinoma cancer and uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma, respectively.

The heat map in Fig. 5 shows that lung squamous cell carcinoma had the highest number of cancer-specific driver DEGs with high-degree centrality (399), while prostate adenocarcinoma had the lowest number (113).

Benchmarking validation

A good overlap (319 genes out of 895, 35.6%) was found between our computational approach and the other well-validated computational methods considered in this study (Additional file 4). 10%, 6.8%, 3.2%, 1.9% and 1.1% was the percentage of overlap with three, four, five, six and seven methods, respectively (Table 4).

Other tools provided a better overlap with two of the other well-validated computational methods. The percentage of overlapping ranged from about 20% (iPAC), 50% (CoMDP and MSEA), to 90% (MDPFinder and MeMo) with a mean of 76%. CoMDP, MSEA, MDPFinder and MeMo found in total 264 genes of the 319 obtained by our method. Thus, our method was able to find 55 genes out of 319 (17.2%), which had not been found using these four tools, and 32 genes out of 895 (3.6%) which had not been found using the other 15 tools (ALDH3B1, BIRC5, CFB, CLPS, COX7A2, COX7B, DNA2, GABARAPL1, GADD45B, GAS1,GNG2, GNG7, GNRH1, GSTT1, IDO1, LSM7, LTC4S, NAIP, PAFAH1B3, PIP5KL1, PNP, POLD4, PPP1R1B, PPP1R3E,PRIM2, PSME2, RFXANK, RPA3, RPP25, TUBA1A, VAMP2 and VAMP8). Although some of the other tools were able to find new cancer driver genes (MSEA found 83, CoMDP 6), the two tools that obtained the best overlap (MDPFinder and MeMo) were not able to discover new cancer driver genes.

In silico validation

Using independent GEO datasets, we calculated the performance of our method in the classification of cancer versus normal samples, for each cancer type (Fig. 6). ROC curves and AUC values are shown for the top ten cancer-specific driver DEGs (with high-degree centrality) with the highest AUC performance. The genes TAP1 and FEN1 achieved the best AUC performance in bladder urothelial carcinoma (AUC = 0.928 and AUC = 0.903), CA4 and RRM2 were the best predictors in breast invasive carcinoma cancer (AUC = 0.89 and AUC = 0.88), ACADM and CD22 in colon adenocarcinoma (AUC = 1), ALDH6A1, GLA and MCM3 in esophageal carcinoma (AUC = 1), GAD1 and PLIN1 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (AUC = 0.83, and AUC = 0.83).

The best performances were obtained in kidney chromophobe, kidney renal clear cell carcinoma and kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma datasets. Top ten genes for these cancers almost always obtained AUC = 1 (Fig. 6). In kidney chromophobe, the mean AUC for the genes, ranked between 11 and 50, was 0.96 and for those genes, ranked between 51 and 100, the AUC was 0.83. In kidney renal clear cell carcinoma mean AUC for the genes with a rank between 11 and 50 was 0.97, and for those ranked between 51 and 100, the AUC was 0.91. In kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma, the mean AUC for the genes ranked between the 11th and the 50th position was 0.96, and for those ranked between the fifty-one and the cent position was 0.87 (Table 5).

CA4 and HMOX1 achieved the best AUC performance (AUC = 0.9 and AUC = 0.89) in liver hepatocellular carcinoma, LTC4S and NEUROD1 in lung adenocarcinoma (AUC = 0.998 and AUC = 0.994), FANCA and ARG2 in lung squamous cell carcinoma (AUC = 0.992 and AUC = 0.956).

The lowest AUC performance was achieved in prostate adenocarcinoma with AKR1B1 and CA12 (AUC = 0.659 and AUC = 0.651). The low performance in this dataset may be due to the low number of DEGs (1860,Table 3) obtained in DEA. Furthermore, the major issue in investigating this cancer was the low number of normal tissues for a comparison with tumour tissues in TCGA data (52 normal tissues).

PAFAH1B3 and AHCYL2 achieved the best AUC performance in rectum adenocarcinoma (AUC = 0.992), AKR1C4 and DNA2 in stomach adenocarcinoma (AUC = 0.983 and AUC = 0.98), GALE and SLC4A4 in thyroid carcinoma (AUC = 0.956 and AUC = 0.935); BRIP1 and GLI2 in uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (AUC = 0.949).

PAFAH1B3 has been proposed as a driver cancer gene [46], while AHCYL2, which is highly expressed in the gastrointestinal tract [47], has been found to be highly downregulated in the gene expression profiling of colorectal tumour [48]. Despite being expressed specifically in the liver and stomach [47], AKR1C4 has been proposed as a possible target for cancer therapy in these tumours [49]. DNA2 nuclease has a role in the mechanism of double strand break repair and its mutation has been reported in gastric and colorectal carcinomas [50]. In malignant thyroid nodules, a different expression of GALE has been reported [51], while SLC4A4 has been included in a 15-gene profile proposed as diagnostic biomarkers of thyroid tumour [52].

Discussion

The main limitation of current tools that analyze pathways, such as KEGG or Biocarta, is that they attribute the same role to each gene within a pathway in accomplishing the cellular function, without taking into account the effect of multiple gene interactions in performing that function.

Our approach considers, for what we believe is the first time, the integration of biological multiplex networks (such as physical interaction, genetic interaction, shared protein domains, co-localization, and functional reaction interactions) in pathways. Our method is based on a well-validated approach (the GANPA/LEGO method), based on the hypothesis that if one gene is functionally connected in the pathway with more genes than those expected (according to the functional networks), its role is functionally central in that pathway. Our approach is therefore an extension of the GANPA/LEGO method that defines key driver genes if they are highly connected in at least two interaction types simultaneously. We used this concept to reveal the gene drivers for multi pathways and networks, and developed a novel method for pan-cancer analysis. On the other hand, GANPA/LEGO [9, 10] was applied for expression-based gene set enrichment analysis. GANPA/LEGO attributes a weight for each gene in a pathway, based on the degree centrality index and its association with other genes inside and outside the pathway, according to the functional network. Weighted genes in pathways are then used to detect pathways with a significant expression change. To sum up, the aim of the two approaches is different, however the greatest difference of our approach is the multilayer analysis.

Since previous studies have shown that the absence of mutations in genes with a high degree centrality is vital for the organism survival [18], we found a list of 1322 network genes highly connected in at least two networks for each pathway, and we studied their behavior in 16 different types of cancer.

Biological role of the key cancer driver DEGs

Our method was effective. Indeed, 67% (895/1322 genes) of the driver genes that we obtained were deregulated in at least one cancer type in TCGA data (Table 3). Our analysis identified several known cancer driver genes (Additional file 3), such as KRAS, PIK3CA, BRCA, BCL2, which regulate crucial pathways involved in apoptosis (i.e., BCL2, BAX, BCL2L1/11), hypoxia and energy metabolism (i.e., GNG4/7, ADCY5/7/8/9), angiogenesis (i.e., HLA-G/F, FGF5) and proliferation (i.e., BRIP1, BRCA1, TOPBP1, BLM) [13, 15]. Our method also revealed a lower probability of finding false positive DEGs than the DEG-based method alone, as demonstrated by the results shown in Fig. 4.

Of the 102 driver genes present in at least four networks (Fig. 3), we found that PSMA, PSMB, and PSMD were the cancer driver genes with a crucial role in the proteasome pathway (with also RPN1/2, PSMA3/5/6/7, PSMB2/3/4/8/9, PSMD2/3/4/7/11/12/14). Proteasome degradation is a crucial mechanism controlling abundance, protein aging and the activity of important protein regulators of cellular signal transduction including a variety of cellular proto-oncogenes [53]. Many preclinical studies have shown that proteasome inhibitors can induce apoptosis in cancer cell lines and murine models of cancer [54]. Unfortunately, however, chemoresistance to proteasome inhibitors can occur thus blocking its pharmacological activity [54]. Our approach could be useful to study driver genes of this pathway and to show how their deregulation in cancer can influence the entire pathway, thus suggesting a potential target of intervention to prevent and overcome chemoresistance.

In addition, among 102 genes, we found some genes belonging to POL and Period families (i.e. POLM, POLR3K, POLR2K) [55, 56], confirming the central role of DNA replication and the circadian rhythm in tumourigenesis [57], respectively.

Of the 895 genes, we found some genes of the mitochondrial respiration process (i.e., COX6A1, COX7A2). Mitochondrial energy metabolism is a well-known process that is altered in tumors [58] and among our 102 genes we have found several genes belonging to this pathway (i.e., GNGT1/2/11, GNG2). Energy metabolism has a high impact on other processes [59], such as apoptosis (BCL2, BCL2L1, BCL2L11), ROS production (i.e., COX5A) and cell cycle control (i.e., MCM protein family, RFC2/4/5).

Signal transduction genes (i.e., ADCY4/7/8/9,) are also in the list of our 102 genes, which also includes cancer stem cell signaling genes (i.e., WNT7A, GLI1/2/3, NOTCH2/3/4, ALDH1A3). Genome instability and DNA damage repair genes (i.e., XRCC protein family, PARP family member, FANC protein members), included in the list of our 102 genes, are among the genes that are altered in several cancers [60, 61].

Looking for those genes with a role in the hallmarks of cancer [62], we generated Fig. 7, in which each circle represents one of the hallmark functions altered in cancer. The roles of genes in the hallmarks of cancer were obtained from KEGG and Reactome databases [5, 62, 63].

The list of cancer driver DEGs for each cancer also enabled us to highlight a series of pathways with a known cancer-specific role. Fig. 8 shows the cancer-specific pathways enriched by cancer driver DEGs for each cancer type considered in this study.

Our method identified 32 cancer driver DEGs which were found by none of the other 15 tools. These genes have important potential roles in metabolism (ALDH3B1, COX7A2, COX7B, GSTT1, IDO1, LSM7, LTC4S, PAFAH1B3, PNP, RPP25, TUBA1A), apoptosis (BIRC5, GADD45B), immune response (CFB, IDO1), DNA repair (DNA2), signal transduction (GAS1,GNG2, GNRH1, PPP1R1B) and proliferation (POLD4, PRIM2, PSME2, RPA3).

ALDH3B1 is an enzyme involved in the metabolism of endogenous and exogenous aldehydes and plays a critical role in maintaining cellular homeostasis [64]. ALDH proteins seem to have different, but not completely understood, roles in cancer. ALDH3B1 also acts against cellular oxidative stress by detoxifying aldehydes derived from ethanol metabolism and lipid peroxidation [64]. COX7A2 and COX7B, involved in energy metabolism, are components of the mitochondrial respiratory chain [65]. A correlation has been hypothesized between alterations in mitochondrial morphology and the reduced expression of COX7A2 in esophageal adenocarcinoma patients [65]. GSTT1 is involved in the metabolism of glutathione by catalyzing the detoxification of potential carcinogens [66]. Polymorphisms in this gene are associated with different types of cancer (e.g. oral, breast) [67, 68]. IDO1 is a catabolic enzyme involved in the pathways of tryptophan metabolism and plays a role in immune suppression [69] The increased expression of IDO1 in ovarian, endometrial and colorectal cancers has been associated with poor survival outcomes [69]. In addition, based on their immunosuppressive functions, IDO1 is becoming a potential target for drug discovery in cancer immunotherapy [70]. BIRC5 and GADD45B are involved in apoptosis, one of the most important hallmarks of cancer. They are known diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic biomarkers in many tumours, such as gynecological, squamous cell carcinoma, and renal cell carcinoma [71,72,73,74,75,76]. POLD4, PRIM2, PSME2, and RPA3 are involved in cellular proliferation and genomic stability. Altered expression in these genes is associated with several tumours [77,78,79,80,81].

Overall, our approach detects both well-known cancer genes, as well as potential novel candidates.

Comparison with other tools

Several approaches have been described to reveal cancer driver genes, but few methods have considered how the functional networks are affected by gene deregulation in cancer and have demonstrated how the integrative analysis of pathways and networks can be used effectively to identify key pathway patterns in cancer.

We compared our results with those obtained, in at least two methods, by 15 current different approaches and we found that almost 36.5% of our genes have been obtained by other methods. This thus suggests the reliability of our approach.

What makes our approach unique is its ability to identify the common/distinct biological processes involved in different cancer types. The above 15 algorithms mainly deal with the design of a static pathway by integrating genomic data, while our method enabled us to combine functional networks, based on multiple sources, with pathways and gene expression information.

We grouped 15 current tools into three groups, based on: 1) mutation profiles, 2) mutation profiles in functional pathways, and 3) integration of multi-omics data (Fig. 9).

The first group includes ActiveDriver [27], OncodriveCLUST [41], e-Driver [38], OncodriveFM [32] and Simon [30]. With these tools cancer drivers were defined as 1) genes with unexpected mutation rates in phosphorylation-specific regions (ActiveDriver), 2) proteins with higher-than-expected mutation rates regardless of the protein regions (OncodriveCLUST), 3) proteins with somatic missense mutations in different protein functional regions, such as domains and intrinsically disordered regions (e-Driver), 4) genes analyzing the impact of mutations on the protein function (OncodriveFM and Simon). With respect to the above mentioned tools, our algorithm creates functional interactions between gene drivers and pathways. The integration of this information enables the genes to be selected that have a central role in biological processes and the generation of relationship among them.

The second group includes Dendrix [28] and CoMDP [35], two software tools that use an alternative approach to identify cancer driver genes: they examine mutations in the context of functional pathways. Compared to the tools in this group, our algorithm creates more functional interactions within pathways in order to obtain only a limited number of genes in the pathways that are highly connected.

The third group combines multi-omics data to overcome the mutational heterogeneity of cancer. This group includes MutsigCV [33], MDPFinder [29], DriverNet [37], DawnRank [36], iPAC [39], MSEA [40], NetBox [31] and MeMo [34]. MutsigCV was applied to exome sequences and gene expression levels, while MDPFinder is an integrative model of mutation and expression data used to identify biologically relevant gene sets. DriverNet associates the presence of a mutated gene with its influence on the gene expression levels of its known interacting genes. DawnRank detects personalized molecular drivers ranking potential driver genes on the basis of their impact on the overall differential expression of their downstream genes in the molecular interaction network. iPAC identifies driver genes with frequent copy-number alterations and corresponding changes in expression that are collectively enriched with respect to biological processes. MSEA integrates summary-level disease association data, functional genomics (such as expression quantitative trait loci, eQTLs, and ENCODE annotations), pathways, and gene networks to obtain disease-associated gene subnetworks and key regulatory genes. NetBox integrates the information of networks with sequence mutations and DNA copy number alterations. The underlying hypothesis of the NetBox tool is that gene networks are constituted by functional modules (sets of connected genes) critical for cancer hallmarks. The alterations of different combinations of genes can influence each module. NetBox identifies candidate driver mutations from perturbed modules. Similarly to NetBox, MeMo identifies candidate driver networks in cancers by focusing on modules that are recurrently altered and that exhibit patterns of mutually exclusive genetic alterations across multiple patients. Unlike Netbox, MeMo uses gene expression in addition to somatic mutations and copy numbers.

Compared to our approach, in the definition of cancer drivers, none of the existing methods are able to integrate different networks, pathways and gene expression in order to create a relationship among them. Our multi-layer profiles are able to extract for each driver, the information on the involved multi-pathways and multi-networks on regulatory pattern. To date the integration of multi-layer profiles has never been used to identify cancer driver genes.

Furthermore, the majority of the available methods use mutation data to detect cancer drivers, however this feature does not clarify the related molecular mechanisms. For example, mutations can exert very diverse effects, such as inducing a premature stop codon, reducing the dosage of mRNA transcripts or affecting the coding region of a gene, thus impacting on the protein function. However this does not necessarily mean that all abnormal genes are involved in the development of cancer. In fact, many aberrations have only mild or neutral effects, and the real drivers, i.e. those that promote the cancer phenotype, are only a minority.

Conclusions

Gene signatures are often not reproducible in the sense that the inclusion or exclusion of a few patients can lead to different sets of selected genes which are difficult to interpret in a biological context. It is thus crucial to identify a limited number of genes that are central to the correct biological processes and which, if altered, can lead to pathological conditions.

To identify these genes, we have proposed an approach that integrates knowledge on the functional pathways and multiple gene-gene (protein-protein) interactions into gene selection algorithms. The challenge is to obtain more stable biomarker signatures, which are also more easily interpretable from a biological perspective.

The study of networks and pathways can also provide further hypotheses of the mechanisms of driver genes.

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

Area Under Curve

- DEA:

-

differential expression analysis

- FDR:

-

False Discovery Rate

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

References

Cava C, Colaprico A, Bertoli G, Bontempi G, Mauri G, Castiglioni I. How interacting pathways are regulated by miRNAs in breast cancer subtypes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2016 Nov 8;17(Suppl 12):348. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-016-1196-1.

Colaprico A, Cava C, Bertoli G, Bontempi G, Castiglioni I. Integrative analysis with Monte Carlo cross-validation reveals miRNAs regulating pathways cross-talk in aggressive breast cancer. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:831314. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/831314.

Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, Harris MA, Hill DP, Issel-Tarver L, Kasarskis A, Lewis S, Matese JC, Richardson JE, Ringwald M, Rubin GM, Sherlock G. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The gene ontology consortium. Nat Genet. 2000 May;25(1):25–9.

Milacic M, Haw R, Rothfels K, Wu G, Croft D, Hermjakob H, D'Eustachio P, Stein L. Annotating cancer variants and anti-cancer therapeutics in reactome. Cancers (Basel). 2012 Nov 8;4(4):1180–211. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers4041180.

Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Sato Y, Morishima K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017 Jan 4;45(D1):D353–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw1092.

Nishimura D. BioCarta. Biotech Software & Internet Report. 2001;2(3):117–20.

Warde-Farley D, Donaldson SL, Comes O, Zuberi K, Badrawi R, Chao P, Franz M, Grouios C, Kazi F, Lopes CT, Maitland A, Mostafavi S, Montojo J, Shao Q, Wright G, Bader GD, Morris Q. The GeneMANIA prediction server: biological network integration for gene prioritization and predicting gene function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010 Jul;38(Web Server issue):W214–20 doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkq537.

Cantini L, Medico E, Fortunato S, Caselle M. Detection of gene communities in multi-networks reveals cancer drivers. Sci Rep. 2015 Dec 7;5:17386. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep17386.

Fang Z, Tian W, Ji H. A network-based gene-weighting approach for pathway analysis. Cell Res. 2012 Mar;22(3):565–80. https://doi.org/10.1038/cr.2011.149.

Dong X, Hao Y, Wang X, Tian W. LEGO: a novel method for gene set over-representation analysis by incorporating network-based gene weights. Sci Rep. 2016 Jan 11;6:18871. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18871.

He X, Zhang J. Why do hubs tend to be essential in protein networks? PLoS Genet. 2006 Jun 2;2(6):e88.

Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA Jr, Kinzler KW. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013 Mar 29;339(6127):1546–58. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1235122.

Zhang T, Zhang D. Integrating omics data and protein interaction networks to prioritize driver genes in cancer. Oncotarget. 2017 Jul 22;8(35):58050–60. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.19481.

Stratton MR, Campbell PJ, Futreal PA. The cancer genome. Nature. 2009 Apr 9;458(7239):719–24. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07943.

Beroukhim R, Getz G, Nghiemphu L, Barretina J, Hsueh T, Linhart D, Vivanco I, Lee JC, Huang JH, Alexander S, Du J, Kau T, Thomas RK, Shah K, Soto H, Perner S, Prensner J, Debiasi RM, Demichelis F, Hatton C, Rubin MA, Garraway LA, Nelson SF, Liau L, Mischel PS, Cloughesy TF, Meyerson M, Golub TA, Lander ES, Mellinghoff IK, Sellers WR. Assessing the significance of chromosomal aberrations in cancer: methodology and application to glioma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Dec 11;104(50):20007–12.

Network CGAR. Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008 Oct 23;455(7216):1061–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07385.

Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Cancer genes and the pathways they control. Nat Med. 2004 Aug;10(8):789–99.

Ding L, Getz G, Wheeler DA, Mardis ER, McLellan MD, Cibulskis K, Sougnez C, Greulich H, Muzny DM, Morgan MB, Fulton L, Fulton RS, Zhang Q, Wendl MC, Lawrence MS, Larson DE, Chen K, Dooling DJ, Sabo A, Hawes AC, Shen H, Jhangiani SN, Lewis LR, Hall O, Zhu Y, Mathew T, Ren Y, Yao J, Scherer SE, Clerc K, Metcalf GA, Ng B, Milosavljevic A, Gonzalez-Garay ML, Osborne JR, Meyer R, Shi X, Tang Y, Koboldt DC, Lin L, Abbott R, Miner TL, Pohl C, Fewell G, Haipek C, Schmidt H, Dunford-Shore BH, Kraja A, Crosby SD, Sawyer CS, Vickery T, Sander S, Robinson J, Winckler W, Baldwin J, Chirieac LR, Dutt A, Fennell T, Hanna M, Johnson BE, Onofrio RC, Thomas RK, Tonon G, Weir BA, Zhao X, Ziaugra L, Zody MC, Giordano T, Orringer MB, Roth JA, Spitz MR, Wistuba II, Ozenberger B, Good PJ, Chang AC, Beer DG, Watson MA, Ladanyi M, Broderick S, Yoshizawa A, Travis WD, Pao W, Province MA, Weinstock GM, Varmus HE, Gabriel SB, Lander ES, Gibbs RA, Meyerson M, Wilson RK. Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2008 Oct 23;455(7216):1069–75. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07423.

Tenenbaum D (2016). KEGGREST: client-side REST access to KEGG. R package version 1.14.0.

Cava C, Bertoli G, Castiglioni I. Integrating genetics and epigenetics in breast cancer: biological insights, experimental, computational methods and therapeutic potential. BMC Syst Biol. 2015 Sep 21;9:62. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12918-015-0211-x.

Cava C, Colaprico A, Bertoli G, Graudenzi A, Silva TC, Olsen C, Noushmehr H, Bontempi G, Mauri G, Castiglioni I. SpidermiR: An R/Bioconductor Package for Integrative Analysis with miRNA Data. Int J Mol Sci. 2017 Jan 27;18(2). pii: E274. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18020274

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, Weinstein JN, Collisson EA, Mills GB, Shaw KR, Ozenberger BA, Ellrott K, Shmulevich I, Sander C, Stuart JM. The cancer genome atlas pan-cancer analysis project. Nat Genet. 2013 Oct;45(10):1113–20. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2764.

Colaprico A, Silva TC, Olsen C, Garofano L, Cava C, Garolini D, Sabedot TS, Malta TM, Pagnotta SM, Castiglioni I, Ceccarelli M, Bontempi G, Noushmehr H. TCGAbiolinks: an R/Bioconductor package for integrative analysis of TCGA data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016 May 5;44(8):e71. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv1507.

Silva TC, Colaprico A, Olsen C, D'Angelo F, Bontempi G, Ceccarelli M, Noushmehr H. TCGA Workflow: Analyze cancer genomics and epigenomics data using Bioconductor packages. Version 2. F1000Res. 2016 Jun 29 [revised 2016 Jan1];5:1542.

Risso D, Schwartz K, Sherlock G, Dudoit S. GC-content normalization for RNA-Seq data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011 Dec 17;12:480. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-480.

Lex A, Gehlenborg N, Strobelt H, Vuillemot R, Pfister H. UpSet: visualization of intersecting sets. IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph. 2014 Dec;20(12):1983–92. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVCG.2014.2346248.

Reimand J, Wagih O, Bader GD. The mutational landscape of phosphorylation signaling in cancer. Sci Rep. 2013 Oct 2;3:2651. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02651.

Vandin F, Upfal E, Raphael BJ. De novo discovery of mutated driver pathways in cancer. Genome Res. 2012 Feb;22(2):375–85. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.120477.111.

Zhao J, Zhang S, LY W, Zhang XS. Efficient methods for identifying mutated driver pathways in cancer. Bioinformatics. 2012 Nov 15;28(22):2940–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts564.

Youn A, Simon R. Identifying cancer driver genes in tumor genome sequencing studies. Bioinformatics. 2011 Jan 15;27(2):175–81.

Cerami E, Demir E, Schultz N, Taylor BS, Sander C. Automated network analysis identifies core pathways in glioblastoma. PLoS One. 2010 Feb 12;5(2):e8918. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0008918.

Gonzalez-Perez A, Lopez-Bigas N. Functional impact bias reveals cancer drivers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012 Nov;40(21):e169. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks743.

Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Polak P, Kryukov GV, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko A, Carter SL, Stewart C, Mermel CH, Roberts SA, Kiezun A, Hammerman PS, McKenna A, Drier Y, Zou L, Ramos AH, Pugh TJ, Stransky N, Helman E, Kim J, Sougnez C, Ambrogio L, Nickerson E, Shefler E, Cortés ML, Auclair D, Saksena G, Voet D, Noble M, DiCara D, Lin P, Lichtenstein L, Heiman DI, Fennell T, Imielinski M, Hernandez B, Hodis E, Baca S, Dulak AM, Lohr J, Landau DA, CJ W, Melendez-Zajgla J, Hidalgo-Miranda A, Koren A, McCarroll SA, Mora J, Lee RS, Crompton B, Onofrio R, Parkin M, Winckler W, Ardlie K, Gabriel SB, Roberts CW, Biegel JA, Stegmaier K, Bass AJ, Garraway LA, Meyerson M, Golub TR, Gordenin DA, Sunyaev S, Lander ES, Getz G. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature. 2013 Jul 11;499(7457):214–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12213.

Ciriello G, Cerami E, Sander C, Schultz N. Mutual exclusivity analysis identifies oncogenic network modules. Genome Res. 2012 Feb;22(2):398–406. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.125567.111.

Zhang J, LY W, Zhang XS, Zhang S. Discovery of co-occurring driver pathways in cancer. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014 Aug 9;15:271. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-15-271.

Hou JP, Ma J. DawnRank: discovering personalized driver genes in cancer. Genome Med. 2014 Jul 31;6(7):56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-014-0056-8.

Bashashati A, Haffari G, Ding J, Ha G, Lui K, Rosner J, Huntsman DG, Caldas C, Aparicio SA, Shah SP. DriverNet: uncovering the impact of somatic driver mutations on transcriptional networks in cancer. Genome Biol. 2012 Dec 22;13(12):R124. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2012-13-12-r124.

Porta-Pardo E, Godzik A. E-driver: a novel method to identify protein regions driving cancer. Bioinformatics. 2014 Nov 1;30(21):3109–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu499.

Aure MR, Steinfeld I, Baumbusch LO, Liestøl K, Lipson D, Nyberg S, Naume B, Sahlberg KK, Kristensen VN, Børresen-Dale AL, Lingjærde OC, Yakhini Z. Identifying in-trans process associated genes in breast cancer by integrated analysis of copy number and expression data. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53014. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0053014.

Arneson D, Bhattacharya A, Shu L, Mäkinen VP, Yang X. Mergeomics: a web server for identifying pathological pathways, networks, and key regulators via multidimensional data integration. BMC Genomics. 2016 Sep 9;17(1):722. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-016-3057-8.

Tamborero D, Gonzalez-Perez A, Lopez-Bigas N. OncodriveCLUST: exploiting the positional clustering of somatic mutations to identify cancer genes. Bioinformatics. 2013 Sep 15;29(18):2238–44.

Cheng WC, Chung IF, Chen CY, Sun HJ, Fen JJ, Tang WC, Chang TY, Wong TT, Wang HW. DriverDB: an exome sequencing database for cancer driver gene identification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014 Jan;42(Database issue):D1048–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkt1025.

Colaprico A, Olsen C, Cava C, Terkelsen T, Cantini L, Olsen A, Bertoli G, Zinovyev A, Barillot E, Castiglioni I, Papaleo E, Bontempi G MoonlightR: Identify oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes from omics data. R Release 3.4 https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/MoonlightR.html

Davis S, Meltzer PS. GEOquery: a bridge between the gene expression omnibus (GEO) and BioConductor. Bioinformatics. 2007 Jul 15;23(14):1846–7.

Liaw A, Wiener M. Classification and regression by randomforest. R News. 2002;2(3):18–22.

Kohnz RA, Mulvihill MM, Chang JW, Hsu KL, Sorrentino A, Cravatt BF, Bandyopadhyay S, Goga A, Nomura DK. Activity-based protein profiling of oncogene-driven changes in metabolism reveals broad dysregulation of PAFAH1B2 and 1B3 in cancer. ACS Chem Biol. 2015 Jul 17;10(7):1624–30. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschembio.5b00053.

Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson Å, Kampf C, Sjöstedt E, Asplund A, Olsson I, Edlund K, Lundberg E, Navani S, Szigyarto CA, Odeberg J, Djureinovic D, Takanen JO, Hober S, Alm T, Edqvist PH, Berling H, Tegel H, Mulder J, Rockberg J, Nilsson P, Schwenk JM, Hamsten M, von Feilitzen K, Forsberg M, Persson L, Johansson F, Zwahlen M, von Heijne G, Nielsen J, Pontén F. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015 Jan 23;347(6220):1260419.

Chu CM, Yao CT, Chang YT, Chou HL, Chou YC, Chen KH, Terng HJ, Huang CS, Lee CC, SL S, Liu YC, Lin FG, Wetter T, Chang CW. Gene expression profiling of colorectal tumors and normal mucosa by microarrays meta-analysis using prediction analysis of microarray, artificial neural network, classification, and regression trees. Dis Markers. 2014;2014:634123. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/634123.

Zeng CM, Chang LL, Ying MD, Cao J, He QJ, Zhu H, Yang B. Aldo-Keto Reductase AKR1C1-AKR1C4: Functions, Regulation, and Intervention for Anti-cancer Therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2017 Mar 14;8:119. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2017.00119.

Lee SH, Kim YR, Yoo NJ, Lee SH. Mutation and expression of DNA2 gene in gastric and colorectal carcinomas. The Korean Journal of Pathology. 2010;44(4):354–9.

da Silveira Mitteldorf CA, de Sousa-Canavez JM, Leite KR, Massumoto C, Camara-Lopes LH. FN1, GALE, MET, and QPCT overexpression in papillary thyroid carcinoma: molecular analysis using frozen tissue and routine fine-needle aspiration biopsy samples. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011 Aug;39(8):556–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/dc.21423.

Gomez-Rueda H, Palacios-Corona R, Gutiérrez-Hermosillo H, Trevino V. A robust biomarker of differential correlations improves the diagnosis of cytologically indeterminate thyroid cancers. Int J Mol Med. 2016 May;37(5):1355–62. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijmm.2016.2534.

Fuchs SY. The role of ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in oncogenic signaling. Cancer Biol Ther. 2002 Jul-Aug;1(4):337–41.

Manasanch EE, Orlowski RZ. Proteasome inhibitors in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017 Jan 24; https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.206. [Epub ahead of print]

Bournique E, Dall'Osto M, Hoffmann JS, Bergoglio V. Role of specialized DNA polymerases in the limitation of replicative stress and DNA damage transmission. Mutat Res. 2017 Aug 14. pii: S0027–5107(17)30098–2. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2017.08.002

Nebot-Bral L, Brandao D, Verlingue L, Rouleau E, Caron O, Despras E, El-Dakdouki Y, Champiat S, Aoufouchi S, Leary A, Marabelle A, Malka D, Chaput N, Kannouche PL. Hypermutated tumours in the era of immunotherapy: the paradigm of personalised medicine. Eur J Cancer. 2017 Oct;84:290–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2017.07.026.

Maiese K. Moving to the rhythm with clock (circadian) genes, autophagy, mTOR, and SIRT1 in degenerative disease and cancer. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2017;14(3):299–304. https://doi.org/10.2174/1567202614666170718092010.

Kalyanaraman B, Cheng G, Hardy M, Ouari O, Lopez M, Joseph J, Zielonka J, Dwinell MB. A review of the basics of mitochondrial bioenergetics, metabolism, and related signaling pathways in cancer cells: therapeutic targeting of tumor mitochondria with lipophilic cationic compounds. Redox Biol. 2018 Apr;14:316–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2017.09.020.

Zhao Y, Hu X, Liu Y, Dong S, Wen Z, He W, Zhang S, Huang Q, Shi MROS. Signaling under metabolic stress: cross-talk between AMPK and AKT pathway. Mol Cancer. 2017 Apr 13;16(1):79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-017-0648-1.

Wilkes DC, Sailer V, Xue H, Cheng H, Collins CC, Gleave M, Wang Y, Demichelis F, Beltran H, Rubin MA, Rickman DS. A germline FANCA alteration that is associated with increased sensitivity to DNA damaging agents. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2017 Sep;3(5). pii: a001487. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/mcs.a001487

Negrini S, Gorgoulis VG, Halazonetis TD. Genomic instability--an evolving hallmark of cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010 Mar;11(3):220–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm2858.

Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000 Jan 7;100(1):57–70.

Fabregat A, Jupe S, Matthews L, Sidiropoulos K, Gillespie M, Garapati P, Haw R, Jassal B, Korninger F, May B, Milacic M, Roca CD, Rothfels K, Sevilla C, Shamovsky V, Shorser S, Varusai T, Viteri G, Weiser J, Wu G, Stein L, Hermjakob H, D'Eustachio P. The Reactome Pathway Knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx1132.

Marchitti SA, Orlicky DJ, Brocker C, Vasiliou V. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 3B1 (ALDH3B1): immunohistochemical tissue distribution and cellular-specific localization in normal and cancerous human tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 2010 Sep;58(9):765–83. https://doi.org/10.1369/jhc.2009.955773.

Aichler M, Elsner M, Ludyga N, Feuchtinger A, Zangen V, Maier SK, Balluff B, Schöne C, Hierber L, Braselmann H, Meding S, Rauser S, Zischka H, Aubele M, Schmitt M, Feith M, Hauck SM, Ueffing M, Langer R, Kuster B, Zitzelsberger H, Höfler H, Walch AK. Clinical response to chemotherapy in oesophageal adenocarcinoma patients is linked to defects in mitochondria. J Pathol. 2013 Aug;230(4):410–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.4199.

Hayes JD, Pulford DJ. The glutathione S-transferase supergene family: regulation of GST and the contribution of the isoenzymes to cancer chemoprotection and drug resistance. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;30(6):445–600.

Minina VI, Soboleva OA, Glushkov AN, Voronina EN, Sokolova EA, Bakanova ML, Savchenko YA, Ryzhkova AV, Titov RA, Druzhinin VG, Sinitsky MY, Asanov MA. Polymorphisms of GSTM1, GSTT1, GSTP1 genes and chromosomal aberrations in lung cancer patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017 Nov;143(11):2235–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-017-2486-3.

Ludovini V, Antognelli C, Rulli A, Foglietta J, Pistola L, Eliana R, Floriani I, Nocentini G, Tofanetti FR, Piattoni S, Minenza E, Talesa VN, Sidoni A, Tonato M, Crinò L, Gori S. Influence of chemotherapeutic drug-related gene polymorphisms on toxicity and survival of early breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. BMC Cancer. 2017 Jul 26;17(1):502. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-017-3483-2.

Mbongue JC, Nicholas DA, Torrez TW, Kim NS, Firek AF, Langridge WH. The role of Indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase in immune suppression and autoimmunity. Vaccines (Basel). 2015 Sep 10;3(3):703–29. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines3030703.

Thaker AI, Rao MS, Bishnupuri KS, Kerr TA, Foster L, Marinshaw JM, Newberry RD, Stenson WF, Ciorba MA. IDO1 metabolites activate β-catenin signaling to promote cancer cell proliferation and colon tumorigenesis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2013 Aug;145(2):416–425.e1–4. doi: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2013.05.002

Ino K, Yamamoto E, Shibata K, Kajiyama H, Yoshida N, Terauchi M, Nawa A, Nagasaka T, Takikawa O, Kikkawa F. Inverse correlation between tumoral indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in endometrial cancer: its association with disease progression and survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2008 Apr 15;14(8):2310–7. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4144.

Braný D, Dvorská D, Slávik P, Školka R, Adamkov M. Survivin and gynaecological tumours. Pathol Res Pract. 2017 Apr;213(4):295–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prp.2017.02.009.

Khan Z, Khan AA, Yadav H, Prasad GBKS, Bisen PS. Survivin, a molecular target for therapeutic interventions in squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2017 Apr 5;22:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11658-017-0038-0.

Xiong C, Liu H, Chen Z, Yu Y, Liang C. Prognostic role of survivin in renal cell carcinoma: a system review and meta-analysis. Eur J Intern Med. 2016 Sep;33:102–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2016.06.009.

Cheng YM, Tsai CC, Hsu YC. Sulforaphane, a Dietary Isothiocyanate, Induces G2/M Arrest in Cervical Cancer Cells through CyclinB1 Downregulation and GADD45β/CDC2 Association. Int J Mol Sci. 2016 Sep 12;17(9). pii: E1530. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17091530

Guo W, Zhu T, Dong Z, Cui L, Zhang M, Kuang G. Decreased expression and aberrant methylation of Gadd45G is associated with tumor progression and poor prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2013 Dec;30(8):977–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10585-013-9597-2.

Hwang IH, SY O, Jang HJ, Jo E, Joo JC, Lee KB, Yoo HS, Lee MY, Park SJ, Jang IS. Cordycepin promotes apoptosis in renal carcinoma cells by activating the MKK7-JNK signaling pathway through inhibition of c-FLIPL expression. PLoS One. 2017 Oct 18;12(10):e0186489. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186489.

Huang QM, Tomida S, Masuda Y, Arima C, Cao K, Kasahara TA, Osada H, Yatabe Y, Akashi T, Kamiya K, Takahashi T, Suzuki M. Regulation of DNA polymerase POLD4 influences genomic instability in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2010 Nov 1;70(21):8407–16. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.

Liu D, Zhang XX, Xi BX, Wan DY, Li L, Zhou J, Wang W, Ma D, Wang H, Gao QL. Sine oculis homeobox homolog 1 promotes DNA replication and cell proliferation in cervical cancer. Int J Oncol. 2014 Sep;45(3):1232–40. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2014.2510.

Milioli HH, Santos Sousa K, Kaviski R, Dos Santos Oliveira NC, de Andrade Urban C, de Lima RS, Cavalli IJ, de Souza Fonseca Ribeiro EM. Comparative proteomics of primary breast carcinomas and lymph node metastases outlining markers of tumor invasion. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2015 Mar-Apr;12(2):89–101.

Dai Z, Wang S, Zhang W, Yang Y. Elevated expression of RPA3 is involved in gastric cancer tumorigenesis and associated with poor patient survival. Dig Dis Sci. 2017 Aug 1; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-017-4696-6.

Acknowledgements

Not Applicable

Funding

The authors would like to thank for the financial support: INTEROMICS flagship project (http://www.interomics.eu/home), National Research Council CUP Grant B91J12000190001, and the project grant SysBioNet, Italian Roadmap Research Infrastructures 2012.

Availability of data and materials

Not Applicable

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CC made substantial contributions to conception and design of the work, in data analysis and drafting the manuscript. GBE made substantial contributions to the interpretation of data. CC, AC, CO, and GBO conducted machine learning analysis. IC made substantial contributions guiding and revising the work critically for important intellectual content and has been involved in drafting the manuscript, answering the referees’ comments and given final approval of the version to be published. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not Applicable

Consent for publication

Not Applicable

Competing interests

None of the authors have any competing interests.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Shows potential driver genes for each pathway and network. (XLSX 415 kb)

Additional file 2:

Shows the results obtained by our method applied to the different networks identifying 1322 genes that are common in at least two networks. (XLSX 23 kb)

Additional file 3:

Shows 895 cancer driver genes. (XLSX 18 kb)

Additional file 4:

Shows cancer driver genes identified by our method (319/895) that were found in at least two of the different methods considered. (XLSX 10 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Cava, C., Bertoli, G., Colaprico, A. et al. Integration of multiple networks and pathways identifies cancer driver genes in pan-cancer analysis. BMC Genomics 19, 25 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-017-4423-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-017-4423-x