Abstract

Background

Chronic migraine is a disabling condition that is currently underdiagnosed and undertreated. In this narrative review, we discuss the future of chronic migraine management in relation to recent progress in evidence-based pharmacological treatment.

Findings

Patients with chronic migraine require prophylactic therapy to reduce the frequency of migraine attacks, but the only currently available evidence-based prophylactic treatment options for chronic migraine are topiramate and onabotulinumtoxinA. Improved prophylactic therapy is needed to reduce the high burden of chronic migraine in Italy. Monoclonal antibodies that target the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) pathway of migraine pathogenesis have been specifically developed for the prophylactic treatment of chronic migraine. These anti-CGRP/R monoclonal antibodies have demonstrated good efficacy and excellent tolerability in phase II and III clinical trials, and offer new hope to patients who are currently not taking any prophylactic therapy or not benefitting from their current treatment.

Conclusions

Treatment of chronic migraine is a dynamic and rapidly advancing area of research. New developments in this field have the potential to improve the diagnosis and provide more individualised treatments for this condition. Establishing a culture of prevention is essential for reducing the personal, social and economic burden of chronic migraine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chronic migraine (CM), defined by the current International Headache Society classification of headache disorders (ICHD-3) as headache occurring on ≥15 days/month for > 3 months with features of migraine on ≥8 days/month [1], is a disabling condition that affects 0.5% to 5% of the general population [2, 3]. However, the true prevalence of CM is difficult to estimate because of heterogeneous data collection instruments, differences in diagnostic strategies between headache centres, patient recall bias, and the potential for patients to overestimate headache frequency, especially if they have psychiatric comorbidities. Compared with episodic migraine (EM), CM is less common but is associated with greater headache-related disability, higher impact on physical, social and occupational functioning, and worse health-related quality of life [2, 4, 5]. Patients with CM also have an increased incidence of co-morbid psychiatric and medical conditions [6, 7], resulting in complex cases of chronic multidimensional migraine. Despite the considerable individual and societal consequences of CM, it remains an underdiagnosed and undertreated condition worldwide [2, 8], and Italy is no exception [9, 10].

Migraine has been conceptualised as a continuum that ranges from EM to CM, with variations in headache days per month and symptoms [11]. About 3% of patients with EM progress to CM each year [11,12,13], but there is a natural within-patient variation in headache-day frequency, meaning that patients can fluctuate between EM and CM [14]. This natural fluctuation needs to be considered when clinicians diagnose and treat CM [14]. Accompanying symptoms of CM can include nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia and osmophobia, but nausea, vomiting, photophobia and phonophobia are often less pronounced with CM than with EM [15].

The mechanisms underlying the progression of EM to CM are complex and not fully understood; however, modifiable risk factors for progression include the frequency of headache attacks, overuse of acute migraine medication, ineffective acute treatment, stressful life events and obesity [8, 12, 16, 17]. Medication-overuse headache (MOH) is now considered a sequela rather than a cause of migraine and can co-exist with CM [1, 18, 19]. In addition to risk factor modification, and the appropriate and effective acute treatment of migraine, all patients with CM need prophylactic treatment to reduce the headache frequency, severity and associated disability [8, 20]. However, low proportions of patients who are candidates for prophylactic treatment actually receive it [8]. Within Europe, prophylactic treatment appears to be particularly underused in Italy [10].

This review summarises strategies for the prophylactic treatment of CM, and highlights the importance of creating a culture for the timely prevention of CM.

Search methods

As this is a narrative review, we did not conduct a systematic literature search. However, a search of the PubMed database was conducted in May 2018, with no date limits, using the search terms “chronic migraine” and “treatment”, and the results were screened for relevance to the review topic. Articles were also added based on the authors’ knowledge of the area.

Understanding the pathophysiology of chronic migraine

The pathophysiology of CM is not fully understood, but there is evidence to indicate that functional changes occur in the brains of patients with CM, including increased cortical hyperexcitability, central trigemino-thalamic sensitisation and defective descending pain modulatory activity [21,22,23]. It is postulated that recurring migraine episodes and comorbid conditions, such as medication overuse or anxiety/depression, may lead to dysfunction of pain modulation pathways, with reduced nociceptive thresholds and atypical release of nociceptive molecules [11, 22]. This may cause increasing central sensitisation of the trigeminal and thalamic neurons, with little recovery between attacks, leading to progression from EM to CM [22, 24]. Cutaneous allodynia and increased activation of the trigeminovascular pathway, both of which occur in migraine [25, 26], implicate hyperexcitability of certain central nervous system structures and increased release of nociceptive neuropeptides, such as calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), which is highly expressed in trigeminal neurons in the central and peripheral nervous system [11, 21, 24, 27]. The crucial role of CGRP in headache pain notwithstanding, the first step of the migraine attack is likely to involve central mechanisms, as suggested by functional neuroimaging findings of a hypothalamic involvement during the early attack stages [28], as well as the concept that migraine may occur without pain in the paediatric population (migraine-associated periodic syndromes) and in patients who experience migraine with aura.

CGRP, which is involved in pain modulation, perception and sensitisation, seems to have a major role in the pathogenesis of migraine {Goldberg, 2015 #47;Ho, 2010 #21;Edvinsson, 2019 #139}. Activation of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, which coexist with CGRP in the same nociceptive neurons, promotes excitation of the trigeminovascular pathway, release of CGRP and pain [29,30,31]. At the central neuronal level, release of CGRP is thought to contribute to cortical spreading depression, which is a key pathophysiological component of migraine with aura [32, 33]. Release of CGRP from peripheral trigeminal fibres is also believed to cause vasodilation and mast cell degranulation, resulting in a persistent pro-inflammatory sensitisation inducing trigeminal nociceptors sensitisation [27]. Interictal levels of CGRP in peripheral blood are higher in patients with CM than EM [34], suggesting altered interictal activity of the trigeminal nervous system in CM [35].

Treatment of chronic migraine

Some patients with low frequency EM can be managed with effective acute therapy (i.e. drugs taken during the prodrome or the migraine attack to abort it) without prophylactic treatment, but patients with CM invariably require prophylactic treatment [8, 36]. Whereas the goal of acute therapy is to abort a migraine attack once it has started, the goals of prophylactic treatment are to prevent attacks, thereby reducing headache frequency, severity and associated disability and decreasing reliance on acute treatment, which may be contributing to concurrent MOH [8, 20]. An additional goal may be to prevent progression of EM to CM in patients with high frequency EM [8]. Patients with EM can be treated with recommended prophylactic therapy based on the number of attacks > 4 and the degree of disability.

In patients with CM, acute treatment options, such as analgesics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and triptans, should be reserved for clearly defined exacerbations of headache [8, 20, 36]. Opioid- and barbiturate-containing medication should also be avoided because of their strong association with MOH [12, 20]. Triptans are migraine-specific medications that inhibit the release of CGRP by activation of presynaptic 5HT1 receptors (Fig. 1) [29, 31, 37]. However, triptans are inappropriate for the treatment of CM because patients should not take them more often than 2 to 3 days per week to avoid developing MOH [8, 20, 31]. Effective acute treatment of migraine attacks with triptans may help to prevent progression from EM to CM, but rather than relying on taking drugs to stop migraine attacks after they have started, the aim of treatment for CM should be the prevention of migraine attacks [35].

Mechanisms of action of antimigraine treatments used in chronic migraine and emerging treatments in relation to calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP). Modified with permission from Benemei, et al. J Headache Pain 2013;14:71 [29]

Current prophylactic treatment options

The first-line treatment of CM is pharmacological [35]. Although there is evidence in support of the use of non-invasive peripheral neurostimulation methods for the prevention of CM [38, 39], most neurostimulation-based and neuromodulatory treatment techniques need further investigation and should be reserved for the most challenging and intractable cases of CM [8, 35, 36]. Behavioural management techniques (e.g. cognitive therapy, exercise, stress management), alternative physical therapies (e.g. acupuncture) and nutraceutical therapies (e.g. supplementary magnesium, riboflavin and Coenzyme Q10) can all be used to complement pharmacological therapy [35, 40].

Numerous orally administered drugs are used for the prophylaxis of CM, including beta-blockers (propranolol, metoprolol), anticonvulsants (valproate, topiramate), calcium-channel blockers (flunarizine), tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline, nortriptyline), serotonin antagonists (pizotifen, methysergide), antihypertensives (lisinopril, candesartan), and antidepressants that act as serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (venlafaxine), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (paroxetine, fluvoxamine) or noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (mirtazapine) [41]. Treatments that are effective for EM are not necessarily effective for CM [11], but evidence for the efficacy of oral agents in CM is generally extrapolated from studies in patients with high-frequency EM [20, 36, 42]. Insufficient efficacy and/or adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation often occur with these drugs in patients with CM [43,44,45]. OnabotulinumtoxinA (OBT-A), which is a formulation of botulinum toxin A administered by intramuscular injection, and topiramate are the only currently available therapies with high-quality evidence for the preventive therapy of CM from more than one randomised controlled trial [20, 36, 42].

OnabotulinumtoxinA

To date, OBT-A is the only treatment specifically approved for the prevention of CM in the EU [46]. OBT-A has been available in Italy since 2013, where it has the highest level of recommendation for the prophylactic treatment of CM [41, 46, 47]. OBT-A has been shown to be an effective and generally well tolerated treatment for the prevention CM in the Phase III Research Evaluating Migraine Prophylaxis Therapy (PREEMPT) trials [48, 49], and tends to be better tolerated than various oral prophylactic treatments, including topiramate [50,51,52,53]. Based on the PREEMPT clinical trial paradigm, OBT-A is administered to at least 31 injection sites across 7 head and neck muscles, and is currently recommended as a second-line option for patients who have not responded adequately or are intolerant of commonly prescribed oral migraine treatments [47]. Treatment should be repeated every 3 months. It is thought that injection of OBT-A in the trigeminally-innervated cranio-facial-cervical region inhibits release of CGRP from peripheral nociceptive neurons and interferes with TRP channels (Fig. 1), thereby reducing neuronal hyperexcitability and peripheral and central sensitisation [11, 46]. It is hypothesised that trigeminal-targeted preventative treatments counteract the impingement of nociceptive input from highly sensitised trigeminal neurons on brain stem second order neurons, thus preventing central sensitisation, a key pathophysiological mechanisms of CM.

Topiramate

Like OBT-A, topiramate has the highest level of recommendation for the prophylactic treatment of CM in Italian treatment guidelines [41]. Although topiramate reduced headache days versus placebo and was relatively well tolerated in patients with CM in two large randomised controlled trials [54, 55], adverse events commonly associated with topiramate include paresthesia, memory and concentration disturbances, fatigue and nausea [41]. It is believed that topiramate is able to prevent the development of cortical spreading depression associated with migraine by modulating ion channels (e.g. blockade of voltage-gated sodium channels) and neurotransmitter release (e.g. inhibition of glutamate), resulting in inhibition of neuronal hyperexcitability [11, 32].

Emerging prophylactic treatments targeting CGRP

There is still an unmet need for more effective, better tolerated prophylactic therapies aimed specifically at patients with CM or high-frequency EM [20]. CGRP and its receptor are well-validated targets for CM, and monoclonal antibodies against CGRP or its receptor are proving very promising for CM prophylaxis in clinical trials [56,57,58].

CGRP receptor antagonists

Small molecule CGRP receptor antagonists are thought to act by blocking the CGRP receptors in the central nervous system and peripheral tissues (Fig. 1), thereby inhibiting the physiological and cellular effects of CGRP [59]. Initially formulated for the acute management of migraine, CGRP receptor antagonists provided the proof of principle that targeting the CGRP pathway may effectively prevent migraine [27, 60]. Telcagepant has been investigated for the prevention of EM, and although CNS penetration is modest, randomised controlled trial data showed a reduction in headache days with telcagepant versus placebo [61]. However, the clinical development of telcagepant was discontinued because of hepatotoxicity concerns, and the development of several other CGRP receptor antagonists has also been discontinued because of safety concerns, formulation issues or unknown reasons [56]. Three CGRP receptor antagonists are currently in phase III development for migraine (atogepant, rimegepant, and ubrogepant), with atogepant and rimegepant being investigated as prophylactic treatment in EM [56, 62]; no studies of CGRP receptor antagonists have been conducted in patients with CM [56, 60].

Anti-CGRP/R monoclonal antibodies

Anti-CGRP antibodies are macromolecules that bind to the CGRP ligand or its receptor neutralising the effects of excessive CGRP released in the trigeminal sensory nerve fibres during migraine attacks (Fig. 1) [27, 60, 63]. Three anti-CGRP/R antibodies are approved in the US and Europe for the prophylactic treatment of CM: fremanezumab [64, 65] and galcanezumab [66, 67], which target the CGRP ligand; and erenumab [68, 69], which targets the CGRP receptor. A fourth anti-CGRP/R antibody against the CGRP ligand, eptinezumab, is currently under review by the US Food and Drug Administration [70]. These macromolecule anti-CGRP/R antibodies have been specifically designed for prophylactic use in CM and frequent EM, and to overcome safety issues associated with CGRP receptor antagonists [27, 57]. They are highly specific for their CGRP/R target, have no ability to cross the blood brain barrier, and bypass liver metabolism so CNS-related effects and hepatotoxicity are unlikely [71]. Erenumab, fremanezumab and galcanezumab are administered subcutaneously, and eptinezumab is administered intravenously [58]. Their long half-lives allow for dosing once a month, all four actives, or once every 3 months, for fremanezumab only [58, 60].

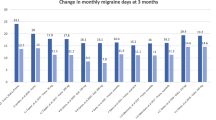

The results of two phase II trials and one phase III trial demonstrating the efficacy and safety of anti-CGRP/R monoclonal antibodies as prophylactic therapy in patients with CM have been published thus far [72,73,74]. In phase II trials, monthly injections of erenumab or fremanezumab for 3 months resulted in significant reductions in the primary endpoints of monthly migraine days and headache hours, respectively, versus placebo [63, 74]. In a randomised, double-blind phase III trial, monthly (675 mg dose at baseline and 225 mg at weeks 4 and 8) or quarterly (single 675 mg dose followed by placebo at weeks 4 and 8) injections of fremanezumab were similarly effective in significantly reducing both the average number of headache days/month and migraine days/month compared with placebo in the 12-week period after the first dose [73]. In relation to the number of headache days/month, a treatment effect was observed within 4 weeks after the initial dose. Anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies were well tolerated in these trials. Mild to moderate injection site reactions were the most common treatment-related adverse events. Long-term safety data are not yet available. Fremanezumab is currently under review by the European Medicines Agency for the prophylactic treatment of chronic and episodic migraine [75, 76] . This review will be based on data from the pivotal phase III studies in these indications [73, 77].

Chronic migraine management in Italy

On the basis of the results of a worldwide web-based survey, the mean total direct annual cost per CM patient (considering healthcare provider visits, hospitalisations, procedures and medications) in Italy was estimated to be €2648 versus €828 for EM [78]. Similarly, a study conducted in an Italian tertiary headache center reported that the total annual cost per CM patient was €2250 versus €523 for EM [79]. Most of the cost of CM is carried by the National Health Service (NHS) [79].

Current problems

CM management in Italy is largely inadequate and expensive because of clinical and operational issues. Currently, patients with CM in Italy are managed at tertiary referral headache centres, but long waiting lists and the paucity of specialists at each center can hinder timely access to high-quality multidisciplinary care [80].

Given the heterogeneity of CM and debated ICHD clinical diagnostic criteria, patients with CM tend to be misdiagnosed [9, 81]. Patients with CM frequently undergo unnecessary procedures, such as electroencephalography and cervical spine imaging [81]. Furthermore, these expensive procedures are often repeated for no apparent reason other than inadequate traceability of their clinical history [81]. Problems diagnosing CM and different data collection instruments and strategies among headache centers mean that the true prevalence and cost of CM in Italy is not known.

It is also apparent that a high proportion of patients with CM do not receive prophylactic therapy in Italy [9, 10, 79]. In Italy, physicians may prescribe off-label treatment at their discretion after receiving informed consent from the patient, and many patients who are prescribed prophylactic medications are using drugs that are not evidence-based [9]. In its current definition, CM includes subgroups of patients with very different levels of severity and outcome [81, 82]. These subgroups are currently not recognised, and there is no strategy to tailor and optimise prophylactic therapy according to individual patient needs. As well as considering the frequency of migraine, effective individualisation of therapy would require careful assessment of clinical characteristics of migraine in each CM patient, as well as their overall medical history [82, 83]. In general, it seems likely that suboptimal use of potentially beneficial evidence-based prophylactic treatment is contributing to the high economic burden of CM in Italy.

Moving towards a more rationalised and personalised treatment approach

The recent approval of OBT-A and promising phase II and III clinical trial results with anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies for the prophylactic treatment of CM opens encouraging new therapeutic scenarios for CM management [81]. It prompts us to rethink our approach to CM in terms of customised healthcare, and to better define different CM phenotypes, endophenotypes and biological markers of response so as to facilitate best use of evidence-based prophylactic treatment options [81, 82]. There is an urgent need for a shared clinical and scientific management strategy that will shed light on neglected areas of clinical governance in relation to CM, minimise the risk of misdiagnosis, rationalise healthcare resource allocation and ensure that patients receive the treatment that best suits their clinical and personal needs. For example, establishing diagnostic and care plans, similar to the one implemented in Palermo for the management of pediatric headache [84], would provide a clear pathway through the diagnostic process, and would help to eliminate redundancy and unnecessary diagnostic procedures or treatments and channel appropriate patients to specialised care in multidisciplinary headache centers. These centers are best placed to identify patients with CM or EM that is trending towards chronicity, and particularly to make a differential diagnosis in patients with other conditions that can mimic CM. Ultimately, such a strategy would reduce the burden of CM on patients and the NHS.

The availability of a national CM register of CM will facilitate a move away from clinical empiricism towards precision medicine [85]. The Italian CM register now includes patient data from 28 headache centers and is soon to involve all Italian headache centers. The results of an exploratory pilot study of the Italian CM register have been published [81]. This study involved 63 consecutive patients with CM seen at four tertiary referral headache centers, where they were screened by specifically trained neurologists using a dedicated semi-structured questionnaire to gather information on variables such as lifestyle, behavioral and socio-demographic factors, comorbidities, migraine features before and after chronification (e.g. disease duration; location, quality and intensity of pain; attack duration and frequency; allodynia; unilateral cranial autonomic symptoms; previous acute and prophylactic treatments); and healthcare resource utilisation. The collected data revealed that most patients had symptoms linked to peripheral trigeminal activation (e.g. unilateral pain, pulsating quality, severe intensity). It was suggested that this simple clinical tool, using easily obtainable clinical details, could help to define different CM endophenotypes and predict responsiveness to topimarate, to OBT-A and anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies [81]. In support of this, there is some evidence to suggest that OBT-A may be most effective in patients with higher interictal blood levels of CGRP and intense peripheral trigeminal activation [83, 86]. The database pilot study also uncovered neglected areas of clinical governance, such as inappropriate hospitalisations, procedures and medications, confirming the view that much work is needed to rationalise and optimise the management of CM in Italy.

Creating a culture of prevention

An improvement in the use of appropriate prophylactic medication is clearly needed to reduce the burden of CM in Italy. The availability of effective and well tolerated new treatment strategies that are specifically indicated for the prophylaxis of CM may help to focus attention on preventive rather than acute treatment of migraine attacks in patients with CM. To this end, neurologists, general practitioners, pharmacists and patients all need to be well informed about CM and the new treatment options.

As observed with OBT-A in the PREEMPT clinical trial program [48], introduction of effective prophylactic therapy early after the onset of chronicity may result in greater benefits [47]. To make best use of prophylactic therapies such as OBT-A and anti-CGRP antibodies, it is therefore important to identify patients with CM and offer them prophylactic treatment as early as possible [47]. In order to identify patients with CM early in the course of the chronicity, patients with high-frequency EM should be monitored closely for headache frequency and new onset CM.

In addition to ensuring that patients with CM receive the best available prophylactic medication early after the onset of chronicity, prevention of chronification in patients with high-frequency EM would also help to limit the burden of CM and should be prioritised [87]. Modification of risk factors or the use of effective therapy has not been prospectively shown to prevent chronification, but it has been suggested that the risk of progression may potentially be reduced by a combined treatment approach of acute treatment to reduce migraine severity and prophylactic treatments to reduce migraine frequency [11]. A pooled analysis of clinical trial results suggests that prophylactic treatment with topiramate in patients with EM may help to prevent migraine chronification [88]. Anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies may also prove to be useful in this regard, as suggested by the results of a phase II clinical trial in which fremanezumab significantly reduced migraine days versus placebo in patients with high-frequency migraine [72].

Although in this review we focus on the pharmacological prevention of CM, patient education, lifestyle factors, overuse of acute medication, and comorbidities all need to addressed in a multidisciplinary treatment plan to ensure optimal management of CM [20]. Patients should be well informed about CM and the treatment they are prescribed, and encouraged to take an active role in managing their condition by adopting positive lifestyle behaviors (e.g. regular sleep, meals and exercise routines), avoiding triggering and aggravating factors, and collaborating with their physician on a long-term treatment strategy [47].

Final considerations

The recent introduction of OBT-A and positive phase II and III clinical trial results with anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies for the prophylactic treatment of CM offers new hope for the many patients with CM who are currently not taking any prophylactic therapy or benefitting from their current treatment. In particular, monoclonal antibodies specifically targeting the CGRP pathway promise a major step forward for the prophylactic treatment of CM. However, to realise the full therapeutic potential of these drugs and effectively reduce the burden of CM in Italy, there is a need for increased disease awareness among both patients and physicians, more accurate diagnosis of CM and individualised evidence-based prophylactic treatment strategies.

However, we need to learn lessons from the past. The availability of triptans in 1990s created awareness about headaches and CM, but appropriate prescription of triptans by both general practitioners and specialists took a long time. Lessons from this time should inform our implementation of novel prophylactic agents for CM to ensure cost-effective use of these agents. The mechanism of action of these treatments is so specific to migraine that inappropriate use will almost invariably result in treatment failure, which in turn may make prescribers wary about the efficacy of these agents for patients who could actually benefit.

To reduce the risk of diagnostic error and avoid incorrect treatment practices with topiramate, OBT-A and anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies, patients with CM should be managed at specialist headache centers, where they will receive a high level of multidisciplinary care. Going forward, patient profiles in Italy will be recorded on a national CM register, which will facilitate easy identification of patient subgroups who may respond to specific CM therapies. The national register will also support a shared patient management strategy among headache specialists.

Ideally, biochemical and clinical markers of therapeutic efficacy will be identified so that potential good responders to topiramate, OBT-A or anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies can be targeted for treatment, thereby maximising the cost-effective use of these treatments. High interictal levels of CGRP and symptoms linked to peripheral trigeminal activation are possible candidates, but much research will be required before possible markers of therapeutic efficacy are used in routine clinical practice. The next phase of research should also aim to assess whether OBT-A and anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies may also be used to prevent or delay transition of high-frequency EM to explicit CM.

Conclusions

Significant advances are currently being made in the prophylactic treatment of CM, which open new and promising scenarios in CM management. These advances should prompt us to rethink the approach to this devastating disease and empower us to be vigilant and continue scientific clinical research, bearing in mind that only a common, shared clinical and scientific management strategy will improve CM ascertainment, distinguish phenotypes and biological markers, shed light on neglected clinical governance areas, provide customised healthcare and tailored therapy, optimise economic resources allocation and reduce the personal, social and economic burden of CM. It is up to us to ensure that newly established and emerging treatment options, such as OBT-A and the new anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies, are used to their best effect within a wider culture of prevention so as to significantly reduce the personal, social and economic impact of this devastating disease.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- CGRP:

-

Calcitonin gene-related peptide

- CM:

-

Chronic migraine

- EM:

-

Episodic migraine

- ICHD-3:

-

International Headache Society classification of Headache Disorders

- MOH:

-

Medication-overuse headache

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

- OBT-A:

-

OnabotulinumtoxinA

- PREEMPT:

-

Phase III Research Evaluating Migraine Prophylaxis Therapy

- TRP:

-

Transient receptor potential

References

International Headache Society. International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) -3. (2018). http://www.ichd-3.org/1-migraine/1-3-chronic-migraine/. Accessed 23 Apr 2018

Bigal ME, Serrano D, Reed M, Lipton RB (2008) Chronic migraine in the population burden, diagnosis, and satisfaction with treatment. Neurology. 71(8):559–566

Natoli J, Manack A, Dean B, Butler Q, Turkel C, Stovner L et al (2010) Global prevalence of chronic migraine: a systematic review. Cephalalgia. 30(5):599–609

Buse D, Manack A, Serrano D, Reed M, Varon S, Turkel C et al (2012) Headache impact of chronic and episodic migraine: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention study. Headache. 52(1):3–17

Bigal ME, Rapoport AM, Lipton RB, Tepper SJ, Sheftell FD (2003) Assessment of migraine disability using the migraine disability assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire: a comparison of chronic migraine with episodic migraine. Headache. 43(4):336–342

Buse D, Manack A, Serrano D, Turkel C, Lipton R (2010) Sociodemographic and comorbidity profiles of chronic migraine and episodic migraine sufferers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 81(4):428–432

Meletiche DM, Lofland JH, Young WB (2001) Quality-of-life differences between patients with episodic and transformed migraine. Headache. 41(6):573–578

Lipton RB, Silberstein SD (2015) Episodic and chronic migraine headache: breaking down barriers to optimal treatment and prevention. Headache. 55(Suppl 2):103–122

Cevoli S, D'Amico D, Martelletti P, Valguarnera F, Del Bene E, De Simone R et al (2009) Underdiagnosis and undertreatment of migraine in Italy: a survey of patients attending for the first time 10 headache centres. Cephalalgia. 29(12):1285–1293

Katsarava Z, Mania M, Lampl C, Herberhold J, Steiner TJ (2018) Poor medical care for people with migraine in Europe - evidence from the Eurolight study. J Headache Pain. 19(1):10

Aurora SK, Brin MF (2017) Chronic migraine: an update on physiology, imaging, and the mechanism of action of two available pharmacologic therapies. Headache. 57(1):109–125

Bigal ME, Serrano D, Buse D, Scher A, Stewart WF, Lipton RB (2008) Acute migraine medications and evolution from episodic to chronic migraine: a longitudinal population-based study. Headache. 48(8):1157–1168

Scher AI, Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Lipton RB (2003) Factors associated with the onset and remission of chronic daily headache in a population-based study. Pain. 106(1–2):81–89

Serrano D, Lipton RB, Scher AI, Reed ML, Stewart WBF, Adams AM et al (2017) Fluctuations in episodic and chronic migraine status over the course of 1 year: implications for diagnosis, treatment and clinical trial design. J Headache Pain. 18(1):101

Yalin OO, Uluduz D, Ozge A, Sungur MA, Selekler M, Siva A (2016) Phenotypic features of chronic migraine. J Headache Pain. 17:26

Bigal ME, Lipton RB (2006) Modifiable risk factors for migraine progression. Headache. 46(9):1334–1343

Katsarava Z, Buse DC, Manack AN, Lipton RB (2012) Defining the differences between episodic migraine and chronic migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep 16(1):86–92

GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1211–59.

Ferrari A, Baraldi C, Sternieri E (2015) Medication overuse and chronic migraine: a critical review according to clinical pharmacology. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 11(7):1127–1144

Sun-Edelstein C, Rapoport AM (2016) Update on the pharmacological treatment of chronic migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep 20(1):6

Mathew NT (2011) Pathophysiology of chronic migraine and mode of action of preventive medications. Headache. 51(s2):84–92

Su M, Yu S (2018) Chronic migraine: A process of dysmodulation and sensitization. Mol Pain. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744806918767697

Diener HC, Dodick DW, Goadsby PJ, Lipton RB, Olesen J, Silberstein SD (2012) Chronic migraine—classification, characteristics and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol 8(3):162–171

Goadsby PJ, Holland PR, Martins-Oliveira M, Hoffmann J, Schankin C, Akerman S (2017) Pathophysiology of migraine: a disorder of sensory processing. Physiol Rev 97(2):553–622

Burstein R, Yarnitsky D, Goor-Aryeh I, Ransil BJ, Bajwa ZH (2000) An association between migraine and cutaneous allodynia. Ann Neurol 47(5):614–624

Noseda R, Burstein R (2013) Migraine pathophysiology: anatomy of the trigeminovascular pathway and associated neurological symptoms, cortical spreading depression, sensitization, and modulation of pain. Pain. 154(Suppl 1):S44–S53

Goldberg SW, Silberstein SD (2015) Targeting CGRP: a new era for migraine treatment. CNS Drugs 29(6):443–452

Schulte LH, May A (2016) The migraine generator revisited: continuous scanning of the migraine cycle over 30 days and three spontaneous attacks. Brain 139(Pt 7):1987–1993

Benemei S, De Cesaris F, Fusi C, Rossi E, Lupi C, Geppetti P (2013) TRPA1 and other TRP channels in migraine. J Headache Pain. 14(1):71

Benemei S, Fusi C, Trevisan G, Geppetti P (2014) The TRPA1 channel in migraine mechanism and treatment. Br J Pharmacol 171(10):2552–2567

Dussor G, Yan J, Xie JY, Ossipov MH, Dodick DW, Porreca F (2014) Targeting TRP channels for novel migraine therapeutics. ACS Chem Neurosci 5(11):1085–1096

Costa C, Tozzi A, Rainero I, Cupini LM, Calabresi P, Ayata C et al (2013) Cortical spreading depression as a target for anti-migraine agents. J Headache Pain. 14:62

Tozzi A, de Iure A, Di Filippo M, Costa C, Caproni S, Pisani A et al (2012) Critical role of calcitonin gene-related peptide receptors in cortical spreading depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109(46):18985–18990

Cernuda-Morollon E, Larrosa D, Ramon C, Vega J, Martinez-Camblor P, Pascual J (2013) Interictal increase of CGRP levels in peripheral blood as a biomarker for chronic migraine. Neurology. 81(14):1191–1196

May A, Schulte LH (2016) Chronic migraine: risk factors, mechanisms and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol 12(8):455–464

Weatherall MW (2015) The diagnosis and treatment of chronic migraine. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 6(3):115–123

Ho TW, Edvinsson L, Goadsby PJ (2010) CGRP and its receptors provide new insights into migraine pathophysiology. Nat Rev Neurol 6(10):573–582

Kinfe TM, Pintea B, Muhammad S, Zaremba S, Roeske S, Simon BJ et al (2015) Cervical non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) for preventive and acute treatment of episodic and chronic migraine and migraine-associated sleep disturbance: a prospective observational cohort study. J Headache Pain 16:101

Straube A, Ellrich J, Eren O, Blum B, Ruscheweyh R (2015) Treatment of chronic migraine with transcutaneous stimulation of the auricular branch of the vagal nerve (auricular t-VNS): a randomized, monocentric clinical trial. J Headache Pain. 16:543

Tepper SJ (2015) Nutraceutical and other modalities for the treatment of headache. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 21(4 Headache):1018–1031

Sarchielli P, Granella F, Prudenzano MP, Pini LA, Guidetti V, Bono G et al (2012) Italian guidelines for primary headaches: 2012 revised version. J Headache Pain. 13(Suppl 2):S31–S70

Cho SJ, Song TJ, Chu MK (2017) Treatment update of chronic migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep 21(6):26

Ford JH, Jackson J, Milligan G, Cotton S, Ahl J, Aurora SK (2017) A real-world analysis of migraine: a cross-sectional study of disease burden and treatment patterns. Headache. 57(10):1532–1544

Hepp Z, Bloudek LM, Varon SF (2014) Systematic review of migraine prophylaxis adherence and persistence. J Manag Care Pharm 20(1):22–33

Hepp Z, Dodick DW, Varon SF, Gillard P, Hansen RN, Devine EB (2015) Adherence to oral migraine-preventive medications among patients with chronic migraine. Cephalalgia. 35(6):478–488

Frampton JE, Silberstein S (2018) OnabotulinumtoxinA: a review in the prevention of chronic migraine. Drugs. 78(5):589–600

Tassorelli C, Tedeschi G, Sarchielli P, Pini LA, Grazzi L, Geppetti P et al (2018) Optimizing the long-term management of chronic migraine with onabotulinumtoxinA in real life. Expert Rev Neurother 18(2):167–176

Aurora SK, Dodick DW, Turkel CC, DeGryse RE, Silberstein SD, Lipton RB et al (2010) OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 1 trial. Cephalalgia. 30(7):793–803

Diener HC, Dodick DW, Aurora SK, Turkel CC, DeGryse RE, Lipton RB et al (2010) OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 2 trial. Cephalalgia. 30(7):804–814

Blumenfeld AM, Schim JD, Chippendale TJ (2008) Botulinum toxin type a and divalproex sodium for prophylactic treatment of episodic or chronic migraine. Headache. 48(2):210–220

Magalhaes E, Menezes C, Cardeal M, Melo A (2010) Botulinum toxin type a versus amitriptyline for the treatment of chronic daily migraine. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 112(6):463–466

Mathew NT, Jaffri SF (2009) A double-blind comparison of onabotulinumtoxina (BOTOX) and topiramate (TOPAMAX) for the prophylactic treatment of chronic migraine: a pilot study. Headache. 49(10):1466–1478

Tassorelli C, Aguggia M, De Tommaso M, Geppetti P, Grazzi L, Pini LA et al (2017) Onabotulinumtoxin a for the management of chronic migraine in current clinical practice: results of a survey of sixty-three Italian headache centers. J Headache Pain. 18(1):66

Diener HC, Bussone G, Van Oene JC, Lahaye M, Schwalen S, Goadsby PJ (2007) Topiramate reduces headache days in chronic migraine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Cephalalgia. 27(7):814–823

Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Dodick DW, Freitag FG, Ramadan N, Mathew N et al (2007) Efficacy and safety of topiramate for the treatment of chronic migraine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Headache. 47(2):170–180

Barbanti P, Aurilia C, Fofi L, Egeo G, Ferroni P (2017) The role of anti-CGRP antibodies in the pathophysiology of primary headaches. Neurol Sci 38(Suppl 1):31–35

Deen M, Correnti E, Kamm K, Kelderman T, Papetti L, Rubio-Beltran E et al (2017) Blocking CGRP in migraine patients - a review of pros and cons. J Headache Pain. 18(1):96

Israel H, Neeb L, Reuter U (2018) CGRP monoclonal antibodies for the preventative treatment of migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep 22(5):38

Salvatore CA, Kane SA (2011) CGRP receptor antagonists: toward a novel migraine therapy. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 12(10):1671–1680

Tso AR, Goadsby PJ (2017) Anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies: the next era of migraine prevention? Curr Treat Options Neurol 19(8):27

Ho TW, Connor KM, Zhang Y, Pearlman E, Koppenhaver J, Fan X et al (2014) Randomized controlled trial of the CGRP receptor antagonist telcagepant for migraine prevention. Neurology. 83(11):958–966

Lipton RB, Croop R, Stock EG, Stock DA, Morris BA, Frost M et al (2019) Rimegepant, an oral calcitonin gene–related peptide receptor antagonist, for migraine. N Engl J Med 381:142–149

Bigal ME, Walter S, Rapoport AM (2015) Therapeutic antibodies against CGRP or its receptor. Br J Clin Pharmacol 79(6):886–895

Teva GmbH. Ajovy (fremanezumab) for injection: summary of product characteristics. (2018). https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/product-information/ajovy-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 11 July 2019

Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. Ajovy™ (fremanezumab-vfrm) injection, for subcutaneous use. (2018). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/761089s000lbl.pdf. Accessed 11 July 2019

Eli Lilly and Company. Emgality (galcanezumab-glnm) injection, for subcutaneous use: US prescribing information. (2018). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/761063s000lbl.pdf. Accessed 11 July 2019

Eli Lilly Nederland BV. Emgality (galcanezumab) for injection: summary of product characteristics. (2018). https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/emgality-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 11 July 2019

Novartis Europharm Limited. Aimovig (erenumab) for injection: summary of product characteristics. (2018). https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/product-information/aimovig-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 11 July 2019

Amgen Inc. Aimovig™ (erenumab-aooe) injection, for subcutaneous use: US prescribing information. (2018). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/761077s000lbl.pdf. Accessed 11 July 2019

Alder Biopharmaceuticals. Pipeline: eptinezumab. (2019). https://www.alderbio.com/pipeline/eptinezumab/. Accessed 11 July 2019

Edvinsson L (2015) CGRP receptor antagonists and antibodies against CGRP and its receptor in migraine treatment. Br J Clin Pharmacol 80(2):193–199

Bigal ME, Dodick DW, Rapoport AM, Silberstein SD, Ma Y, Yang R et al (2015) Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of TEV-48125 for preventive treatment of high-frequency episodic migraine: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b study. Lancet Neurol 14(11):1081–1090

Silberstein SD, Dodick DW, Bigal ME, Yeung PP, Goadsby PJ, Blankenbiller T et al (2017) Fremanezumab for the preventive treatment of chronic migraine. N Engl J Med 377(22):2113–2122

Tepper S, Ashina M, Reuter U, Brandes JL, Dolezil D, Silberstein S et al (2017) Safety and efficacy of erenumab for preventive treatment of chronic migraine: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol 16(6):425–434

Teva Pharmaceuticals Ltd. European Medicines Agency (EMA) accepts fremanezumab marketing authorization application. (2018). http://www.tevapharm.com/news/european_medicines_agency_ema_accepts_fremanezumab_marketing_authorization_application_02_18.aspx. Accessed 1 May 2018

Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. FDA accepts biologics license application for fremanezumab with priority review for prevention of migraine and grants fast track designation for cluster headache development program. (2017). http://www.drugs.com/nda/fremanezumab_171218.html. Accessed 1 May 2018

Dodick DW, Silberstein SD, Bigal ME, Yeung PP, Goadsby PJ, Blankenbiller T et al (2018) Effect of fremanezumab compared with placebo for prevention of episodic migraine: a randomized clinical trial. Jama. 319(19):1999–2008

Bloudek LM, Stokes M, Buse DC, Wilcox TK, Lipton RB, Goadsby PJ et al (2012) Cost of healthcare for patients with migraine in five European countries: results from the international burden of migraine study (IBMS). J Headache Pain. 13(5):361–378

Berra E, Sances G, De Icco R, Avenali M, Berlangieri M, De Paoli I et al (2015) Cost of chronic and episodic migraine. A pilot study from a tertiary headache centre in Northern Italy. J Headache Pain 16:532

Pellesi L, Benemei S, Favoni V, Lupi C, Mampreso E, Negro A et al (2017) Quality indicators in headache care: an implementation study in six Italian specialist-care centres. J Headache Pain. 18(1):55

Barbanti P, Fofi L, Cevoli S, Torelli P, Aurilia C, Egeo G et al (2018) Establishment of an Italian chronic migraine database: a multicenter pilot study. Neurol Sci 39(5):933–937

Barbanti P, Ferroni P (2017) Onabotulinum toxin a in the treatment of chronic migraine: patient selection and special considerations. J Pain Res 10:2319–2329

Barbanti P, Egeo G (2015) Pharmacological trials in migraine: it's time to reappraise where the headache is and what the pain is like. Headache. 55(3):439–441

Raieli V, Vecchio A, Consolo F, Santangelo G, Pitino R, Porrello G et al (2014) Path diagnostic therapeutic care (PDTA) in children and adolescents with headache. Ital J Pediatr 40(Suppl 1):A85

Pomes LM, Gentile G, Simmaco M, Borro M, Martelletti P (2018) Tailoring treatment in polymorbid migraine patients through personalized medicine. CNS Drugs. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-018-0532-6

Cernuda-Morollon E, Martinez-Camblor P, Ramon C, Larrosa D, Serrano-Pertierra E, Pascual J (2014) CGRP and VIP levels as predictors of efficacy of onabotulinumtoxin type a in chronic migraine. Headache. 54(6):987–995

Martelletti P (2017) The application of CGRP(r) monoclonal antibodies in migraine spectrum: needs and priorities. BioDrugs. 31(6):483–485

Limmroth V, Biondi D, Pfeil J, Schwalen S (2007) Topiramate in patients with episodic migraine: reducing the risk for chronic forms of headache. Headache. 47(1):13–21

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nishad Parkar, PhD, of Springer Healthcare Communications for writing the outline of this manuscript, and Joanne Dalton for writing the first draft of this manuscript, on behalf of Springer Healthcare Communications. This medical writing assistance was funded by Teva Pharmaceuticals.

Funding

Medical writing assistance for the development of this manuscript was funded by Teva Pharmaceuticals.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

The Authors were the members of The Italian chronic migraine group. They contributed equally to this work drafting the manuscript and critically revised the various drafts of the manuscript and approved the final version before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

E. C. Agostoni has no conflict of interest.

P. Barbanti has received fees for participation on advisory boards, as well as research grants and travel grants from Allergan, Allmirall, Electrocore, Eli Lilly, Lusofarmaco, Merck & Co, New Penta, Novartis, Teva and Visufarma.

P. Calabresi received/receives research support, speaker honoraria, and support to attend national and international conferences from: Abbvie, Bayer Schering, Biogen-Dompè, Biogen-Idec, Eisai, Genzyme, Lundbeck, Lusofarmaco, Merck-Serono, Novartis, Prexton, Teva, UCB Pharma, Zambon.

B. Colombo has received congress fee reimbursements from Teva and Novartis.

P. Cortelli, has received honoraria for speaking engagements or consulting activities with Allergan Italia, AbbVie srl, Chiesi Farmaceutici, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Teva, UCB Pharma S.p.A,, Zambon.

F. Frediani has received fees for participation on advisory boards, speaker honoraria or consulting activities from Allergan, Cristalfarma, Ecupharma, Novartis, Teva.

P. Geppetti received/receives research support, speaker honoraria, and support to attend national and international conferences from Novartis, TEVA, Chiesi Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, Allergan, Eli Lilly, Electrocore, IBSA.

L. Grazzi has received consultancy and advisory fees from Allergan SpA, Electrocore LLC, Novartis, TEVA, ElyLilly.

M. Leone has received fees for participation on advisory boards from Eli Lilly and Teva.

P. Martelletti has received fees for participation on advisory boards, as well as research grants and travel grants from Allergan, Electrocore, Elythrapharma, Eli Lilly, Novartis and Teva.

L. A. Pini has received fees for participation on advisory boards, as well as research grants and travel grants from Allergan, Novartis and TEVA.

M. P. Prudenzano has received fees for participation on advisory boards, speaker and editorial honoraria, as well as congress fee reimbursements from Allergan, Almirall, Novartis and Teva.

P. Sarchielli has received fees for participation on advisory boards, as well as research grants.

from Allergan, Novartis, Teva.

G. Tedeschi, has received fees for participation on advisory boards, as well as research grants and travel grants from Allergan, Novartis, Teva, Sanofy, Biogen.

A. Russo, has received congress fee reimbursements from Novartis, Teva and Allergan.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Agostoni, E.C., Barbanti, P., Calabresi, P. et al. Current and emerging evidence-based treatment options in chronic migraine: a narrative review. J Headache Pain 20, 92 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-019-1038-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-019-1038-4