Abstract

Background

The debilitating nature of migraine and challenges associated with treatment-refractory migraine have a profound impact on patients. With the need for alternatives to pharmacologic agents, vagus nerve stimulation has demonstrated efficacy in treatment-refractory primary headache disorders. We investigated the use of cervical non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) for the acute treatment and prevention of migraine attacks in treatment-refractory episodic and chronic migraine (EM and CM) and evaluated the impact of nVNS on migraine-associated sleep disturbance, disability, and depressive symptoms.

Methods

Twenty patients with treatment-refractory migraine were enrolled in this 3-month, open-label, prospective observational study. Patients administered nVNS prophylactically twice daily at prespecified times and acutely as adjunctive therapy for migraine attacks. The following parameters were evaluated: pain intensity (visual analogue scale [VAS]); number of headache days per month and number of migraine attacks per month; number of acutely treated attacks; sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [PSQI]); migraine disability assessment (MIDAS); depressive symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory® [BDI]); and adverse events (AEs).

Results

Of the 20 enrolled patients, 10 patients each had been diagnosed with EM and CM. Prophylaxis with nVNS was associated with significant overall reductions in patient-perceived pain intensity; median (interquartile range) VAS scores at baseline versus 3 months were 8.0 (7.5, 8.0) versus 4.0 (3.5, 5.0) points (p < 0.001). Baseline versus 3-month values (mean ± standard error of the mean) were 14.7 ± 0.9 versus 8.9 ± 0.8 (p < 0.001) for the number of headache days per month and 7.3 ± 0.9 versus 4.5 ± 0.6 (p < 0.001) for the number of attacks per month. Significant improvements were also noted in MIDAS (p < 0.001), BDI (p < 0.001), and PSQI global (p < 0.001) scores. No severe or serious AEs occurred.

Conclusion

In this study, treatment with nVNS was safe and provided clinically meaningful decreases in the frequency and intensity of migraine attacks in patients with treatment-refractory migraine. Improvements in migraine-associated disability, depression, and sleep quality were also noted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

As a highly prevalent neurologic disorder, migraine headache exerts a considerable burden on individuals and society [1, 2], including substantial economic costs [3]. Recent findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 suggest that migraine ranks sixth among the top worldwide causes of disability [4, 5]. Along with premonitory (i.e. aura) and attack-associated symptoms (i.e. phonophobia, photophobia, nausea, and vomiting) [2], patients with migraine are likely to experience sleep disturbances [6, 7] and other comorbidities such as depression and anxiety [8, 9]. Sleep disturbances may trigger a migraine attack in the preictal state [6]. Patients with non-sleep migraine (NSM) demonstrate low thermal pain thresholds, whereas insufficient rest may evoke migraine attacks in patients with sleep migraine (SM) [6, 10].

Although there is no clear consensus on precisely how to define refractory migraine, a key parameter among commonly used clinical definitions is unresponsiveness to medications from multiple pharmacologic classes [11]. Thus, individuals with treatment-refractory migraine require alternatives to standard pharmacologic therapies. Neuromodulation therapy using implanted vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) devices has been successfully used to treat drug-resistant epilepsy [12] and depression [13], and numerous other methods of neuromodulation (e.g. occipital nerve stimulation, non-invasive VNS, transcranial direct current stimulation, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, transcutaneous supraorbital nerve stimulation, spinal cord stimulation) have been investigated for treating patients with migraine, with varying degrees of success [14]. Small studies and case reports have shown that implanted VNS may also alleviate migraine and cluster headache [15–18]. Data suggest that attenuation of pain by VNS occurs via inhibition of signalling through afferent vagus nerve fibres to the trigeminal nucleus caudalis (TNC) [19] and via modulation of inhibitory neurotransmitter release, resulting in decreased glutamate levels in the TNC [20, 21].

The use of implanted VNS devices for the treatment of headache disorders is hampered by inherent procedural risks (i.e. infection, lead migration, lead fracture, and battery replacement), health complications (i.e. voice disturbance, cough, headache, and paraesthesia), surgery cost, and the need for postoperative monitoring [22, 23]. Thus, a non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) device (gammaCore®; electroCore, LLC) has been developed and is CE-marked for the treatment of primary headache disorders [24]. Recent evidence suggests that nVNS is effective in the acute treatment of migraine [25, 26] and in the acute or prophylactic treatment of cluster headache [27–29]. An open-label pilot study that evaluated nVNS for the acute treatment of episodic migraine (EM) attacks reported that the efficacy of nVNS at 2 h after initiation of therapy was comparable to that of first-line pharmacologic interventions [25]. Barbanti and colleagues evaluated the use of nVNS for the acute treatment of migraine attacks in patients with chronic migraine (CM) and high-frequency EM [26]. The majority of patients with mild or moderate migraine attacks achieved pain relief or pain-free status at both 1 and 2 h after nVNS treatment [26].

No published studies to date have examined the effect of nVNS on sleep quality and depression in patients with migraine. We therefore conducted a 3-month, open-label, prospective, observational cohort study to investigate the safety and efficacy of acute and prophylactic nVNS treatment in patients with EM and CM and assess the effects of nVNS on sleep quality in these patients.

Methods

Study design

This was a 3-month, single-centre, open-label, prospective, observational cohort study to evaluate the impact of preventive and acute treatment with nVNS in patients with treatment-refractory EM and CM and migraine-associated sleep disturbances, disability, and depressive symptoms. Patients were referred to our department by a headache specialist (neurologist), and their diagnoses were confirmed by a multidisciplinary pain board consisting of neurologists, anaesthesiologists, neurosurgeons, psychiatrists, and pain nurses.

Ethics, consent, and permissions

Approval for this study was obtained from the institutional ethics committee. All patients provided written informed consent.

Study population

Patients who were diagnosed with EM (headaches occurring <15 days per month) or CM (headaches occurring ≥15 days per month) according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders criteria (3rd edition; beta version) [2] and who fulfilled all of the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria (Table 1) were enrolled. All patients enrolled in the study were considered refractory to prophylactic treatment having previously failed 4 or more classes of medications (i.e. beta [β]-blocker, anticonvulsant, tricyclic antidepressant, and calcium channel blocker) and behavioural therapy.

Stimulation paradigm

The nVNS device (provided by electroCore, LLC, Basking Ridge, NJ, USA) is a handheld, portable appliance that employs a constant voltage-driven signal consisting of a 1-millisecond burst of 5-kHz sine waves repeated at a frequency of 25 Hz, with stimulation intensity ranging from 0 to 24 V. The device is positioned against the side of the neck below the mandibular angle, medial to the sternocleidomastoid muscle and lateral to the larynx. Stimulations are delivered transcutaneously in the region of the cervical branch of the vagus nerve through 2 stainless steel disc electrodes that are manually coated with a conductive gel.

For prophylactic therapy, patients were instructed to administer two 2-min stimulations of nVNS (1 stimulation on each side of the neck in the regions of the right and left cervical vagus nerves) twice daily (morning and late afternoon; total of 4 doses per day) (Fig. 1). For acute therapy, patients were advised to administer two 2-min stimulations (1 stimulation on each side of the neck) at the time of acute medication intake. Before study commencement, all patients received training from the same instructor regarding how to use the device.

Assessments and end points

Data for all efficacy and safety outcomes were obtained from patient-completed headache diaries and by physician questioning during outpatient visits. Efficacy related to prophylactic therapy was assessed by evaluating the change from baseline in patient-reported pain intensity, number of headache days per month, and number of migraine attacks per month. Baseline values for the number of headache days per month and number of migraine attacks per month were determined on the basis of patient reporting and medical history. The efficacy of acute nVNS treatment on individual attacks was assessed using subjective patient reports of overall pain relief or pain freedom as self-reported at baseline and after 3 months of therapy. Data for all reported and treated attacks were pooled and analysed. The onset, severity, and frequency of treatment-related adverse events (AEs) were evaluated. Furthermore, impaired sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [PSQI] score) [30], depressive symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory® [BDI; Psychological Corporation of San Antonio, San Antonio, TX, USA] score) [31], and migraine disability (Migraine Disability Assessment [MIDAS]) scores and grades [32] were evaluated at baseline and after 3 months of nVNS treatment. Sleep disturbances were classified according to the onset of the migraine attack (SM vs NSM) and in relation to the time of sleep evaluation (interictal: 48 h from last attack; or preictal or postictal: <48 h from last attack) (Table 3).

Statistical analysis

Univariate analyses of data obtained at baseline and after 3 months of nVNS treatment were performed to determine changes in pain intensity (visual analogue scale [VAS] score), headache days/month, MIDAS score/grade, number of migraine attacks per month, and depressive (BDI) and sleep (PSQI) comorbidities. Comparisons of the outcomes at baseline and 3 months’ follow-up were performed using the McNemar test for binominal variables and the Student t test or the Wilcoxon signed rank test, as appropriate, for continuous data. P-values <0.05 were considered significant. All patients were included in the analyses; subgroup analyses were performed for patients with EM and CM. Statistical analyses were performed independently by North American Science Associates Inc. (Minneapolis, MN, USA) using SAS® 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Demographic and baseline characteristics

Of the 20 participants, 16 were female and 4 were male, with an average age of 53.1 years (range, 35–72 years). Ten patients each had been diagnosed with EM (9 without aura/1 with aura) and CM (8 without aura/2 with aura). All patients were classified as MIDAS grade III/IV, with most having clinical signs of sleep disturbance (average PSQI score, 8.3 points; range, 2–17 points) and depressive symptoms (average BDI score, 17.3 points; range, 5–34 points) (Table 2). Evaluation of sleep patterns at baseline revealed that of 20 patients, 15 (6 EM/9 CM) had a disturbed sleep architecture (i.e. global PSQI score of >5 points), and most patients (18/20) had NSM (Table 3). The majority of patients (18/20) had body mass index (BMI) values ≤30 kg/m2; 2 patients (1 EM/1 CM) had BMI values >30 kg/m2.

Preventive use of nVNS

Median (interquartile range [IQR]) pain intensity (VAS score) in the total study population was 8 (7.5, 8.0) points at baseline and significantly declined to 4 (3.5, 5) points after 3 months of nVNS use (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). Reductions in pain intensity were observed in both EM (baseline vs 3 months of nVNS treatment: 8 [7, 8] vs 3.5 [3, 4] points; p = 0.002) and CM (8 [8, 8] vs 5 [4, 5] points; p = 0.002) subgroups (Fig. 2). The overall mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) number of headache days per month declined from 14.7 ± 0.9 to 8.9 ± 0.8 days (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3). Similarly, the number of headache days declined in both the EM (11.3 ± 0.6 vs 5.7 ± 0.5 days; p < 0.001) and CM (18.1 ± 0.8 vs 12.1 ± 0.6 days; p < 0.001) subgroups (Fig. 3). The number of migraine attacks per month declined significantly in the total population (7.3 ± 0.9 vs 4.5 ± 0.6 attacks; p < 0.001), the EM subgroup (4.9 ± 0.6 vs 3.0 ± 0.4 attacks; p = 0.02), and the CM subgroup (9.7 ± 1.2 vs 5.9 ± 0.8 attacks; p < 0.001) (Fig. 4).

Pain intensity (median [IQR]). Abbreviations: CM chronic migraine, EM episodic migraine, IQR interquartile range, nVNS non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation, VAS visual analogue scale. Pain intensity (VAS) scores at baseline (blue bars) and after 3 months of treatment with nVNS (orange bars) in all patients, patients with EM, and patients with CM. Data are shown as median (IQR); whiskers indicate the minimum and maximum values

Number of headache days per month (mean ± SEM). Abbreviations: CM chronic migraine, EM episodic migraine, nVNS non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation, SEM standard error of the mean. Number of headache days per month at baseline (blue bars) and after 3 months of treatment with nVNS (orange bars) in all patients, patients with EM, and patients with CM. Baseline measures were determined on the basis of patient reporting and medical history. Data are shown as mean ± SEM

Number of migraine attacks per month (mean ± SEM). Abbreviations: CM chronic migraine, EM episodic migraine, nVNS non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation, SEM standard error of the mean. The number of migraine attacks per month at baseline (blue bars) and after 3 months of treatment with nVNS (orange bars) in all patients, patients with EM, and patients with CM. Baseline measures were determined on the basis of patient reporting and medical history. Data are shown as mean ± SEM

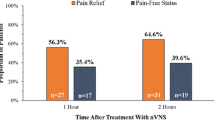

Acute treatment with nVNS

All patients reported that they had treated each of their migraine attacks with adjunctive nVNS during the 3-month treatment phase. Overall, patients with EM treated 90 migraine attacks with nVNS, and patients with CM treated 177 migraine attacks with the device. All patients self-reported at least some overall pain relief with their pre-existing acute treatment at baseline and with adjunctive acute nVNS use at follow-up. Of the 9 patients who reported a maximum benefit of pain relief at baseline, 5 (2 EM/3 CM) were able to achieve pain freedom within 2 h after initiating adjunctive nVNS treatment as reported at 3 months (p = 0.03).

Migraine-associated comorbidities

In the total population, significant reductions were observed in the median (IQR) MIDAS score (baseline vs 3 months of nVNS treatment: 26 [18, 41.5] vs 15 [9, 34.5] points; p < 0.001) and MIDAS grade (3.5 [3, 4] vs 3 [2, 4]; p = 0.008) (Fig. 5a). A significant decrease in the MIDAS score was also observed in the CM subgroup (39 [33, 44] vs 16 [9, 36] points; p = 0.002) but not in the EM subgroup (Fig. 5a).

Migraine disability and migraine-associated comorbidities. Abbreviations: BDI Beck Depression Inventory, CM chronic migraine, EM episodic migraine, IQR interquartile range, MIDAS Migraine Disability Assessment, nVNS non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation, PSQI Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, SEM standard error of the mean. MIDAS (a), BDI (b), and PSQI (c) scores at baseline (blue bars) and after 3 months of nVNS treatment (orange bars) in all patients, patients with EM, and patients with CM. Data are shown as median (IQR) for MIDAS and PSQI (whiskers indicate the minimum and maximum values) and as mean ± SEM for BDI

A significant reduction from baseline to 3 months in the mean ± SEM BDI score was noted in the total population (17.3 ± 1.4 vs 10.8 ± 1.1 points; p < 0.001), the EM subgroup (16.2 ± 1.8 vs 8.4 ± 0.9 points; p < 0.001), and the CM subgroup (18.4 ± 2.1 vs 13.2 ± 1.6 points; p < 0.001) (Fig. 5b).

Similarly, significant reductions in the global PSQI score were observed in the total population (7 [5.5, 11.5] vs 5 [5, 8.5] points; p < 0.001), the EM subgroup (6.5 [5, 8] vs 5 [5, 5] points; p = 0.03), and the CM subgroup (10 [6, 12] vs 8.5 [6, 10] points; p = 0.02) (Fig. 5c and Table 4). Reductions in PSQI subscores were significant in the total population for latency (1 [0.5, 3.5] vs 1 [0.5, 2] point; p = 0.03) and daytime dysfunction (2.5 [2, 4] vs 2 [1, 2] points; p = 0.004) (Table 4). Trends toward lower PSQI subscores after treatment were observed for daytime dysfunction in the EM subgroup (2.5 [2, 4] vs 2 [1, 2] points; p = 0.06) and for latency in the CM subgroup (2.5 [1, 5] vs 2 [1, 3] points; p = 0.06).

Incidence of AEs

Four patients reported mild treatment-related AEs, most commonly neck twitching and skin irritation. These AEs were transient, coincided with the period of stimulation, and resolved during the course of treatment. No severe or serious AEs occurred.

Discussion

In this study, a clinically meaningful response to 3 months of prophylactic nVNS therapy was observed in the overall population as well as in the migraine subgroups (EM and CM), and nVNS was associated with significant reductions in pain intensity and number of headache days per month. A significant decrease in the number of migraine attacks per month was noted in the total population and in both subgroups. After 3 months, MIDAS scores and MIDAS grades significantly decreased in the total population. Significant improvements in BDI and PSQI scores were observed for the total population and for both subgroups. Treatment with nVNS was well tolerated with no serious or severe treatment-related AEs.

Migraine is associated with a considerable economic burden [3], and findings from the International Burden of Migraine Study [33] suggest that therapies aimed at decreasing headache frequency and/or headache-related disability are important in containing costs and reducing the clinical and economic strain of migraine. The significant decreases in the number of headache attacks per month and MIDAS scores that were noted in the current study suggest that nVNS may have substantial utility in this regard.

The limitations of the current study include its open-label design, lack of control arm and prospective run-in period, self-recollected reporting of acute pain relief and pain freedom findings, and its small patient population. The lack of a control arm did not allow for examination of the placebo effect, which has been noted consistently in studies of migraine interventions [25, 34]. The method used for reporting acute pain relief and pain freedom was based on patients’ general impressions and did not involve the use of a validated pain scale.

To date, 2 studies have investigated prophylactic therapy for migraine using non-invasive neuromodulation devices [35, 36]. Findings from the current study are consistent with those reported in a study of prophylactic therapy for CM using non-invasive transcutaneous auricular VNS [35] and those reported in a study of prophylactic therapy for migraine using non-invasive transcutaneous supraorbital stimulation [36]. However, unlike the current study, the aforementioned studies did not evaluate the effect of prophylactic nVNS therapy in both EM and CM subgroups.

This study was the first to examine the effect of nVNS on sleep quality in patients with migraine. Significant improvements in sleep quality after 3 months of treatment with nVNS were observed; however, further studies are required to validate these findings. Results from the current study also confirmed the favourable safety profile of nVNS that was reported in previous studies of nVNS in the treatment of migraine [25, 26]. As first-line pharmacologic therapy for the acute treatment of migraine, triptans (i.e. serotonin 5-HT1B/1D agonists) are associated with a risk for cardiovascular/cerebrovascular side effects [37–39]. Thus, nVNS may serve as a safe alternative to triptans, which may potentially lower the risk for medication-overuse headache [40].

The therapeutic effects of nVNS reported in the current study are supported by findings from human neuroimaging studies and from animal studies of migraine pain and cortical spreading depression (CSD) [21, 41–43]. Functional magnetic resonance imaging studies in patients with migraine reflect heightened sensory facilitation, decreased inhibition in response to sensory stimuli, and lack of or decreased adaptation to interictal stimuli [44]. Neuroimaging studies of VNS demonstrate thalamic involvement, which is responsible for processing somatosensory information and regulating cortical activity [41]. Thus, in patients with migraine, nVNS therapy may help to counteract the decline in thalamocortical activity that is responsible for the decreased habituation to interictal stimuli [45]. The potential role of nVNS in migraine-associated pain and CSD has been investigated in animal studies [21, 42, 43]. In a rat model of trigeminal allodynia, Oshinsky and colleagues demonstrated that nVNS decreased trigeminal nociceptive stimulation by inhibiting nitric oxide–induced increases in glutamate levels in the TNC [21]. Further evaluation of the analgesic effect of VNS suggests that VNS inhibits the increase in c-fos expression in the TNC that occurs in response to painful stimuli [43]. With regard to migraine aura, which is believed to result from CSD [46], Chen and colleagues compared the effect of direct VNS using implanted VNS with the effect of nVNS in a rat model of CSD [42]. Compared with control treatment, both modes of VNS suppressed CSD susceptibility, with nVNS being more effective than direct VNS [42].

Evidence suggests that the degree of response to nVNS may vary depending on the side of stimulation [47]. Examination of cervical vagus nerve morphology at the site of electrode implantation shows that the right vagus nerve has a considerably larger surface area and more tyrosine hydroxylase–positive nerve fibres than the left vagus nerve, which may be relevant with respect to the side of stimulation [47]. Stimulation-mediated sympathetic- and catecholamine-driven effects and variations in the amount of epineurial connective tissue may modulate treatment response [47]. In the current study, patients administered treatment to both the right and left vagus nerves. However, in 3 recently published studies of nVNS for migraine and cluster headache, stimulation in the region of the right vagus nerve was implemented [25, 26, 29].

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that administration of nVNS therapy in patients with treatment-refractory migraine was associated with significant reductions in the monthly number of headache days, a preferred outcome measure in migraine studies, and pain intensity. In addition, there were clinically meaningful improvements in migraine-associated disability, depression, and sleep quality. The role of nVNS in migraine therapy is being further explored in ongoing large-scale, randomised, sham-controlled trials with long-term follow-up.

Abbreviations

- AE:

-

Adverse event

- BDI:

-

Beck Depression Inventory

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CM:

-

Chronic migraine

- CSD:

-

Cortical spreading depression

- EM:

-

Episodic migraine

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- MIDAS:

-

Migraine Disability Assessment

- NSM:

-

Non-sleep migraine

- nVNS:

-

Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation

- PSQI:

-

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

- SEM:

-

Standard error of the mean

- SM:

-

Sleep migraine

- TNC:

-

Trigeminal nucleus caudalis

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

- VNS:

-

Vagus nerve stimulation

References

Hamelsky SW, Stewart WF, Lipton RB (2001) Epidemiology of migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep 5(2):189–194

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (2013) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 33(9):629–808. doi:10.1177/0333102413485658

Lanteri-Minet M (2014) Economic burden and costs of chronic migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep 18(1):385. doi:10.1007/s11916-013-0385-0

Global Burden of Disease Study Collaborators (2015) Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 386(9995):743–800. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4

Steiner TJ, Birbeck GL, Jensen RH, Katsarava Z, Stovner LJ, Martelletti P (2015) Headache disorders are third cause of disability worldwide. J Headache Pain 16:58. doi:10.1186/s10194-015-0544-2

Engstrøm M, Hagen K, Bjørk MH, Stovner LJ, Gravdahl GB, Stjern M, Sand T (2013) Sleep quality, arousal and pain thresholds in migraineurs: a blinded controlled polysomnographic study. J Headache Pain 14:12. doi:10.1186/1129-2377-14-12

de Tommaso M, Delussi M, Vecchio E, Sciruicchio V, Invitto S, Livrea P (2014) Sleep features and central sensitization symptoms in primary headache patients. J Headache Pain 15:64. doi:10.1186/1129-2377-15-64

Malone CD, Bhowmick A, Wachholtz AB (2015) Migraine: treatments, comorbidities, and quality of life, in the USA. J Pain Res 8:537–547. doi:10.2147/JPR.S88207

Pompili M, Serafini G, Di Cosimo D, Dominici G, Innamorati M, Lester D, Forte A, Girardi N, De Filippis S, Tatarelli R, Martelletti P (2010) Psychiatric comorbidity and suicide risk in patients with chronic migraine. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 6:81–91

Engstrøm M, Hagen K, Bjørk MH, Stovner LJ, Sand T (2014) Sleep quality and arousal in migraine and tension-type headache: the headache-sleep study. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl 198:47–54. doi:10.1111/ane.12237

Martelletti P, Katsarava Z, Lampl C, Magis D, Bendtsen L, Negro A, Russell MB, Mitsikostas DD, Jensen RH (2014) Refractory chronic migraine: a consensus statement on clinical definition from the European Headache Federation. J Headache Pain 15:47. doi:10.1186/1129-2377-15-47

Ryvlin P, Gilliam FG, Nguyen DK, Colicchio G, Iudice A, Tinuper P, Zamponi N, Aguglia U, Wagner L, Minotti L, Stefan H, Boon P, Sadler M, Benna P, Raman P, Perucca E (2014) The long-term effect of vagus nerve stimulation on quality of life in patients with pharmacoresistant focal epilepsy: the PuLsE (Open Prospective Randomized Long-term Effectiveness) trial. Epilepsia 55(6):893–900. doi:10.1111/epi.12611

Aaronson ST, Carpenter LL, Conway CR, Reimherr FW, Lisanby SH, Schwartz TL, Moreno FA, Dunner DL, Lesem MD, Thompson PM, Husain M, Vine CJ, Banov MD, Bernstein LP, Lehman RB, Brannon GE, Keepers GA, O'Reardon JP, Rudolph RL, Bunker M (2013) Vagus nerve stimulation therapy randomized to different amounts of electrical charge for treatment-resistant depression: acute and chronic effects. Brain Stimul 6(4):631–640. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2012.09.013

Martelletti P, Jensen RH, Antal A, Arcioni R, Brighina F, de Tommaso M, Franzini A, Fontaine D, Heiland M, Jurgens TP, Leone M, Magis D, Paemeleire K, Palmisani S, Paulus W, May A, European Headache Foundation (2013) Neuromodulation of chronic headaches: position statement from the European Headache Federation. J Headache Pain 14:86. doi:10.1186/1129-2377-14-86

Sadler RM, Purdy RA, Rahey S (2002) Vagal nerve stimulation aborts migraine in patient with intractable epilepsy. Cephalalgia 22(6):482–484

Hord ED, Evans MS, Mueed S, Adamolekun B, Naritoku DK (2003) The effect of vagus nerve stimulation on migraines. J Pain 4(9):530–534

Lenaerts ME, Oommen KJ, Couch JR, Skaggs V (2008) Can vagus nerve stimulation help migraine? Cephalalgia 28(4):392–395. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01538.x

Mauskop A (2005) Vagus nerve stimulation relieves chronic refractory migraine and cluster headaches. Cephalalgia 25(2):82–86. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.00611.x

Bossut DF, Maixner W (1996) Effects of cardiac vagal afferent electrostimulation on the responses of trigeminal and trigeminothalamic neurons to noxious orofacial stimulation. Pain 65(1):101–109

Beekwilder JP, Beems T (2010) Overview of the clinical applications of vagus nerve stimulation. J Clin Neurophysiol 27(2):130–138. doi:10.1097/WNP.0b013e3181d64d8a

Oshinsky ML, Murphy AL, Hekierski H Jr, Cooper M, Simon BJ (2014) Noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation as treatment for trigeminal allodynia. Pain 155(5):1037–1042. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2014.02.009

Ben-Menachem E, Revesz D, Simon BJ, Silberstein S (2015) Surgically implanted and non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation: a review of efficacy, safety and tolerability. Eur J Neurol 22(9):1260–1268. doi:10.1111/ene.12629

Kotagal P (2011) Neurostimulation: vagus nerve stimulation and beyond. Semin Pediatr Neurol 18(3):186–194. doi:10.1016/j.spen.2011.06.005

electroCore. News. Electrocore receives FDA approval for chronic migraine study. http://www.electrocore.com/electrocore-receives-fda-approval-for-chronic-migraine-study. Accessed September 14, 2014.

Goadsby PJ, Grosberg BM, Mauskop A, Cady R, Simmons KA (2014) Effect of noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation on acute migraine: an open-label pilot study. Cephalalgia 34(12):986–993. doi:10.1177/0333102414524494

Barbanti P, Grazzi L, Egeo G, Padovan AM, Liebler E, Bussone G (2015) Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation for acute treatment of high-frequency and chronic migraine: an open-label study. J Headache Pain 16:61. doi:10.1186/s10194-015-0542-4

Kinfe TM, Pintea B, Guresir E, Vatter H (2015) Partial response of intractable cluster-tic syndrome treated by cervical non-invasive vagal nerve stimulation (nVNS). Brain Stimul 8(3):669–671. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2015.01.002

Nesbitt AD, Marin JC, Tompkins E, Ruttledge MH, Goadsby PJ (2015) Initial use of a novel noninvasive vagus nerve stimulator for cluster headache treatment. Neurology 84(12):1249–1253. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000001394

Gaul C, Diener HC, Silver N, Magis D, Reuter U, Andersson A, Liebler E, Straube A (2015) Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation for PREVention and Acute treatment of chronic cluster headache (PREVA): a randomised controlled study. Published online September 21, 2015. http://cep.sagepub.com/content/early/2015/09/21/0333102415607070.full.pdf+html. Cephalalgia. doi:10.1177/0333102415607070

Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ (1989) The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 28(2):193–213

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J (1961) An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 4:561–571

Midas Questionnaire. http://www.migraines.org/disability/pdfs/midas.pdf. Accessed October 2, 2015.

Bloudek LM, Stokes M, Buse DC, Wilcox TK, Lipton RB, Goadsby PJ, Varon SF, Blumenfeld AM, Katsarava Z, Pascual J, Lanteri-Minet M, Cortelli P, Martelletti P (2012) Cost of healthcare for patients with migraine in five European countries: results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). J Headache Pain 13(5):361–378. doi:10.1007/s10194-012-0460-7

Meissner K, Fassler M, Rucker G, Kleijnen J, Hrobjartsson A, Schneider A, Antes G, Linde K (2013) Differential effectiveness of placebo treatments: a systematic review of migraine prophylaxis. JAMA Intern Med 173(21):1941–1951. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.10391

Straube A, Ellrich J, Eren O, Blum B, Ruscheweyh R (2015) Treatment of chronic migraine with transcutaneous stimulation of the auricular branch of the vagal nerve (auricular t-VNS): a randomized, monocentric clinical trial. J Headache Pain 16(1):543. doi:10.1186/s10194-015-0543-3

Schoenen J, Vandersmissen B, Jeangette S, Herroelen L, Vandenheede M, Gerard P, Magis D (2013) Migraine prevention with a supraorbital transcutaneous stimulator: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology 80(8):697–704. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182825055

Goadsby PJ (2000) The pharmacology of headache. Prog Neurobiol 62(5):509–525

Ferrari MD, Roon KI, Lipton RB, Goadsby PJ (2001) Oral triptans (serotonin 5-HT(1B/1D) agonists) in acute migraine treatment: a meta-analysis of 53 trials. Lancet 358(9294):1668–1675. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06711-3

Dodick D, Lipton RB, Martin V, Papademetriou V, Rosamond W, MaassenVanDenBrink A, Loutfi H, Welch KM, Goadsby PJ, Hahn S, Hutchinson S, Matchar D, Silberstein S, Smith TR, Purdy RA, Saiers J, Triptan Cardiovascular Safety Expert Panel (2004) Consensus statement: cardiovascular safety profile of triptans (5-HT agonists) in the acute treatment of migraine. Headache 44(5):414–425. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04078.x

Saper JR, Da Silva AN (2013) Medication overuse headache: history, features, prevention and management strategies. CNS Drugs 27(11):867–877. doi:10.1007/s40263-013-0081-y

Chae JH, Nahas Z, Lomarev M, Denslow S, Lorberbaum JP, Bohning DE, George MS (2003) A review of functional neuroimaging studies of vagus nerve stimulation (VNS). J Psychiatr Res 37(6):443–455

Chen SP, Ay I, Lopes de Morais A, Qin T, Zheng Y, Sadhegian H, Oka F, Simon B, Elkermann-Haerter K, Ayata C (2015) Vagus nerve stimulation inhibits cortical spreading depression. Pain. [published online November 25, 2015].

Multon S, Schoenen J (2005) Pain control by vagus nerve stimulation: from animal to man…and back. Acta Neurol Belg 105(2):62–67

Schwedt TJ, Chiang CC, Chong CD, Dodick DW (2015) Functional MRI of migraine. Lancet Neurol 14(1):81–91. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70193-0

Coppola G, Vandenheede M, Di Clemente L, Ambrosini A, Fumal A, De Pasqua V, Schoenen J (2005) Somatosensory evoked high-frequency oscillations reflecting thalamo-cortical activity are decreased in migraine patients between attacks. Brain 128(Pt 1):98–103. doi:10.1093/brain/awh334

Cui Y, Kataoka Y, Watanabe Y (2014) Role of cortical spreading depression in the pathophysiology of migraine. Neurosci Bull 30(5):812–822. doi:10.1007/s12264-014-1471-y

Verlinden TJ, Rijkers K, Hoogland G, Herrler A (2015) Morphology of the human cervical vagus nerve: implications for vagus nerve stimulation treatment. Acta Neurol Scand. doi:10.1111/ane.12462

Acknowledgements

The authors express their appreciation for the efforts and contributions of all investigators involved in this study. We acknowledge Günther Halfar (employee of electroCore, LLC, Basking Ridge, NJ, USA) for patient training and instruction and the contributions of Carolina Link, MD, Katharina Fassbender (study nurse), and Ute Wegener-Höpfner, MD. Gratitude is expressed to all patients who participated in the study.

Funding

This study was performed without any external funding. The nVNS devices were provided by electroCore, LLC (Basking Ridge, NJ, USA). Statistical analyses for the study were conducted by Candace McClure, PhD, of North American Science Associates Inc. (Minneapolis, MN, USA) and were supported by electroCore, LLC. Editorial support for this manuscript was provided by MedLogix Communications, LLC (Schaumburg, IL, USA) and was paid for by electroCore, LLC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Thomas M. Kinfe, MD, has received training support from St. Jude Medical, Inc. He also serves as a consultant for St. Jude Medical, Inc., and Medtronic Inc. Bogdan Pintea, MD, has received training support from St. Jude Medical, Inc. Bruce J. Simon, PhD, is an employee of electroCore, LLC.

Authors’ contributions

All authors were involved in the development of the study design and participated in data collection and data analyses. All authors contributed to the development of this manuscript and provided their critique and their approval of the final draft for submission to The Journal of Headache and Pain.

Updates

This article was updated on December 22, 2015. A global calculation error has been corrected that affected a significant amount of data reported in the paper, resulting in a substantial change to the text, tables and figures.

This article was updated on December 22, 2015.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kinfe, T.M., Pintea, B., Muhammad, S. et al. Cervical non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) for preventive and acute treatment of episodic and chronic migraine and migraine-associated sleep disturbance: preliminary findings from a prospective observational cohort study. J Headache Pain 16, 101 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-015-0582-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-015-0582-9