Abstract

Treat-to-target (T2T) and dose tapering after obtaining the therapeutic objective (called “treat-to-budget”-T2B-in this Commentary) are the two most commonly used therapeutic strategies in rheumatoid arthritis. In theory, both strategies could add value to the healthcare system, although they are focused on different objectives: T2T strategy improves outcomes but increases short-term costs, while the cost savings obtained through T2B are associated with higher relapse rates. The systematic implementation of both strategies must be founded on solid evidence of their effectiveness and efficiency. However, the level of evidence between guidelines and individual studies is inconsistent for both strategies and the number and the quality of cost-effectiveness analyses is scarce. Raising the level of evidence requires a move from generalization to individualization by conducting randomized clinical trials that assess each of the many strategies that fall under the umbrella of the overall T2T and T2B concepts. In addition, such studies should consider the therapeutic goals and impact of the disease from the perspective of individual patients, which is only possible by promoting shared decision-making.

Funding

Lilly Spain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Treat-to-target (T2T) and dose tapering after obtaining the therapeutic objective (“treat-to-budget”-T2B-) are the two most commonly used therapeutic strategies in rheumatoid arthritis. |

The systematic implementation of both strategies must be founded on solid evidence of their effectiveness and efficiency. |

However, the level of evidence between guidelines and individual studies is inconsistent for both strategies and the number and the quality of cost-effectiveness analyses is scarce. |

Raising the level of evidence requires a move from generalization to individualization by conducting randomized clinical trials that assess each of the many strategies that fall under the umbrella of the overall T2T and T2B concepts. |

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory joint disease characterized by its high prevalence and substantial impact on society and health services. Over the last decade, the systematic use of reliable tools for clinical evaluation, the development of targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (tsDMARDs), and the implementation of new therapeutic strategies have all contributed to a significant improvement in the prognosis of RA [1]. At present, the two most commonly used treatment strategies are treat-to-target (T2T) and dose tapering after obtaining the therapeutic objective.

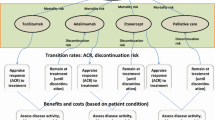

The aim of T2T is to achieve clinical remission or at least a low level of disease activity. The implementation of T2T requires an early diagnosis and must be based on a joint decision made by the doctor and the patient. Disease activity must also be tightly controlled through regular treatment adjustments to reach the therapeutic target. Tapering involves reducing the dose, or increasing the interval between doses, in patients who have achieved remission or a low disease activity. Tapering aims to maintaining the therapeutic goal but at the same time decreasing the risk of adverse effects and the cost of treatment, thereby contributing to the sustainability of healthcare systems, so this strategy could also be dubbed as “treat-to-budget” (T2B). The literature contains excellent reviews of both strategies [2,3,4].

In theory, the combined use of T2T and T2B could add value to the healthcare system. According to Porter’s well-known definition of value, healthcare systems should seek the best health outcomes achieved per dollar spent [5]. Each of the strategies helps improve one of the two components in Porter’s equation, but they can also have a negative impact on the other component. There is evidence suggesting that the T2T strategy improves outcomes, but increases short-term costs; [6] while on the other hand, the cost savings obtained through T2B are associated with a higher relapse rate [7] (Table 1). Given this, the clinical and economic impact of using both strategies, either separately or in combination, cannot be analyzed independently. The total cost (not just the drug-related cost) and clinical outcomes of each strategy must be compared before drawing conclusions about their value. In other words, the cost-effectiveness of T2T and T2B must be analyzed to determine their value.

Most publications into RA management support the use of T2T over that of the usual treatment [2]. The T2T approach has been adopted by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and the Asia Pacific League of Associations for Rheumatology (APLAR) [4], although the level of evidence (LoE) between the guidelines is inconsistent. For instance, the LoE in the EULAR guidelines lies between 1a and 2b, depending on the type of recommendation [8], while it is low or moderate in the ACR guidelines, depending on the type of patient [9]. An exhaustive review by the National Institute for Health Research UK concluded that there was mixed evidence for T2T and only observed clinical benefits in specific patient groups (early RA) for some outcomes [10]. The discrepancy between the guidelines and various individual studies that compare T2T against routine treatment should not come as a surprise. These differences can be explained by the high heterogeneity of the studies, which assessed different types of patients and included distinct study designs, treatment regimens, response criteria, and variables.

T2T increases short-term healthcare costs, however very few researchers have assessed the strategy’s efficiency [11] and even those were low-quality studies [10]. A robust evaluation of efficiency would need to analyze the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio [expressed as additional cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained] for each of the many treatment regimens that fall under the T2T concept in order to check if the cost per QALY gained lies below commonly accepted cost-effectiveness thresholds.

With respect to tapering, the relapse rate depends on the dose reduction regimen, but it is often above 30%, one year after treatment [7]. Different studies show that better outcomes are obtained in patients in sustained remission for at least 6 months and dose reduction or an increase in dosing interval are preferable to treatment discontinuation [12]. It is also known that when relapse occurs, patients respond well to reintroduction of the same drug [12]. It should be noted that most of the evidence on tapering comes from observational studies with a small sample size and only a third are based on randomized clinical trials [7]. A recent single-blind, randomized clinical trial found relapse rates of 33% and 43% (p = 0.17) in the first year after reducing the dose of TNF inhibitors and conventional synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs), respectively [13]. While it is widely accepted that higher doses of biological agents are associated with a greater risk of infection, it is remarkable that tapering studies do not evaluate the decrease in adverse effects before and after applying the strategy, which proves very revealing about the main aim of dose reduction, which seems to focus mostly on impact on efficacy.

The level of evidence and strength of recommendation for the T2B approach in the main guidelines (ACR, EULAR) is at best moderate (2b) and there are no indications as to which is the most appropriate tapering strategy [3, 8, 9]. In contrast to the T2T strategy, which is less widely implemented [14] despite support from a greater LoE, the degree of T2B implementation is relatively high (Table 1) [15, 16], probably because it is easier to put into practice and requires less resources than T2T.

Tapering studies feature a broad heterogeneity in dose reduction regimes, follow-up time, and patient type [7]. There is therefore a need to assess the effectiveness of each dose reduction schedule for each specific drug, while continuing to make progress in the study of predictors of low disease activity and remission to identify which patients might benefit the most from tapering. To date, very few antirheumatic drugs include information on dose reduction results in their summary of product characteristics [17].

Several studies have estimated the direct savings in drug costs derived from tapering, but practically none of them have evaluated its cost-effectiveness [18]. Given that dose reduction tends to increase the rate of relapses, future studies should contemplate a decremental cost-effectiveness analysis, whose results are expressed as cost saved per quality-adjusted life year lost. These results should help decide whether the savings associated with the strategy offset the potential for clinical deterioration [19]. One study used this approach and reported a savings of €390,493 per QALY lost and therefore concluded the strategy was highly effective [20]. However, we cannot assume this finding is true for all tapering regimes because in the given study the dose reduction was not accompanied by a significant increase in relapses, which is unusual compared to most other tapering studies [7].

We are currently experiencing a trend for a convergence between evidence-based and patient-centered medicine [21]. The adoption of strategies such as T2T and T2B should fulfill both objectives, adding value to individual patients and healthcare systems. However, the systematic implementation of these strategies must be founded on solid evidence of their effectiveness and efficiency. Raising the level of evidence requires a move from generalization to individualization by conducting randomized clinical trials that assess each of the many strategies that fall under the umbrella of the overall T2T and T2B concepts. In addition, such studies should take into account the therapeutic goals and impact of the disease from the perspective of individual patients, which is only possible by considering their perspective and promoting shared decision-making.

References

Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Barton A, Burmester GR, Emery P, Firestein GS, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:1. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2018.1.

Stoffer MA, Schoels MM, Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Breedveld FC, Burmester G, et al. Evidence for treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: results of a systematic literature search update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:16–22.

Lau CS, Gibofsky A, Damjanov, Lula S, Marshall L, Jones H, et al. Down-titration of biologics for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review. Rheumatol Int. 2017;37:1789–98.

Smolen JS, Aletaha D. Rheumatoid arthritis therapy reappraisal: strategies, opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11:276–89.

Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2477–81.

Grigor C, Capell H, Stirling A, McMahon AD, Lock P, Vallance R, et al. Effect of a treatment strategy of tight control for rheumatoid arthritis (the TICORA study): a single-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:263–9.

Schett G, Emery P, Tanaka Y, Burmester G, Pisetsky DS, Naredo E, et al. Tapering biologic and conventional DMARD therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: current evidence and future directions. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1428–37.

Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J, Burmester G, Chatzidionysiou K, Dougados M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:960–77.

Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr, Akl EA, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. 2015 American college of rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68:1–25.

Wailoo A, Hock ES, Stevenson M, Martyn-St James M, Rawdin A, Simpson E, et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of treat-to-target strategies in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2017;21:1–258. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta21710.

Vermeer M, Kievit W, Kuper HH, Braakman-Jansen LMA, Bernelot Moens HJ, Zijlstra TR, et al. Treating to the target of remission in early rheumatoid arthritis is cost-effective: results of the DREAM registry. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:350.

Aletaha D, Smolen JS. Diagnosis and management of rheumatoid arthritis: a review. JAMA. 2018;320:1360–72.

van Mulligen E, de Jong PHP, Kuijper TM, van der Ven M, Appels C, Bijkerk C, et al. Gradual tapering TNF inhibitors versus conventional synthetic DMARDs after achieving controlled disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: first-year results of the randomised controlled TARA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:746–53.

Yu Z, Lu B, Agosti J, Bitton A, Corrigan C, Fraenkel L, et al. Implementation of treat-to-target for rheumatoid arthritis in the US: analysis of baseline data from a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res. 2018;70:801–6.

Alperi-López M, Alonso-Castro S, Morante-Bolado I, Queiro-Silva R, Riestra-Noriega JL, Arboleya L, et al. Biological dose tapering in daily clinical practice: a 10-year follow-up study. Reumatol Clin. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reuma.2018.08.002(Epub ahead of print).

Brahe CH, Krabbe S, Østergaard M, Ørnbjerg L, Glinatsi D, Røgind H, et al. Dose tapering and discontinuation of biological therapy in rheumatoid arthritis patients in routine care—2-year outcomes and predictors. Rheumatology. 2019;58:110–9.

Takeuchi T, Genovese MC, Haraoui B, Li Z, Xie L, Klar R, et al. Dose reduction of baricitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis achieving sustained disease control: results of a prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:171–8.

Verhoef LM, Tweehuysen L, Hulscher ME. bDMARD dose reduction in rheumatoid arthritis: a narrative review with systematic literature search. Rheum Ther. 2017;4:1–24.

Nelson AL, Cohen JT, Greenberg D, Kent DM. Much cheaper, almost as good: decrementally cost-effective medical innovation. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:662–7.

Kievit W, van Herwaarden N, van den Hoogen FH, van Vollenhoven RF, Bijlsma JW, van den Bemt BJ, et al. Disease activity-guided dose optimisation of adalimumab and etanercept is a cost-effective strategy compared with non-tapering tight control rheumatoid arthritis care: analyses of the DRESS study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1939–44.

Sacristán JA. Patient-centered medicine and patient-oriented research: improving health outcomes for individual patients. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13:6.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This commentary and the Rapid Service Fee were funded by Lilly Spain.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

José A. Sacristán is an employee of Eli Lilly. Silvia Díaz is an employee of Eli Lilly. Inmaculada de la Torre is an employee of Eli Lilly. José Inciarte is an employee of Eli Lilly. Alejandro Balsa has received grants/research support, fees for consultancies or as a speaker from AbbVie, Pfizer, Novartis, BMS, Nordic, Sanofi, Sandoz, Lilly, UCB and Roche.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9970457.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Sacristán, J.A., Díaz, S., de la Torre, I. et al. Treat-To-Target and Treat-To-Budget in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Measuring the Value of Individual Therapeutic Interventions. Rheumatol Ther 6, 473–477 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-019-00178-3

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-019-00178-3