Abstract

The Persian Gulf, a semi-enclosed sea in the subtropical northwest of the Indian Ocean, is noted for its unique biodiversity under its extreme ecological conditions. Despite high biodiversity levels, many groups of marine invertebrates in this area have remained uninvestigated. The order Zoantharia (zoanthids) is one of these taxonomically neglected groups. In this study, diversity of shallow water zoanthids off the Qeshm Island, the largest island in the Persian Gulf, was investigated for the first time. Using in situ field examination integrated with 16S rDNA sequencing and phylogenetic analysis, the presence of three zoanthid species in the inter-tidal and shallow water zone of Qeshm Island were demonstrated: Zoanthus sansibaricus (n = 12) with five morphotypes, Palythoa cf. mutuki (n = 10) with two morphotypes and Palythoa tuberculosa (n = 4) with just one morphotype. In addition to species identification, molecular examination determined phylogenetic relationships of specimens with other previously reported zoanthid species. While Zoanthus sansibaricus and Palythoa tuberculosa are two known zoanthid species, based on molecular data, Palythoa cf. mutuki is potentially a novel undescribed species. However, due to lack of data on zoanthid research and distribution for the entire Persian Gulf, further investigation is needed to clearly ascertain this matter.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The order Zoantharia (zoanthid) is a group of benthic colonial anthozoans which belongs to the subclass Hexacorallia. They are characterized by having two rows of tentacles and one ventral siphonoglyph (Haddon and Shackleton 1891). These cnidarians are found in many marine ecosystems and are particularly common in coral reef ecosystems worldwide (Burnett et al. 1994, 1995; Reimer et al. 2011). Although zoanthid genera, Zoanthus and Palythoa are common in shallow subtropical and tropical waters, their taxonomy and identification to species level was historically confusing due to the intraspecific variation in polyp shape, size, color, oral disk color (Burnett et al. 1997; Reimer et al. 2004) and the absence of exact morphological description of species in the past literature. In addition, most zoanthids are known for being encrusted by sand and other detritus to enhance their structure, which make their histological sectioning very difficult (Reimer et al. 2010).

Recently, taking advantage of molecular phylogenetic methods, the reorganization process of the classification of this taxonomically neglected group has begun (Reimer and Fujii 2010; Sinniger et al. 2010). The mitochondrial markers have been successfully utilized in examining zoanthid taxa (Sinniger et al. 2010). Applying mt16S rDNA as a DNA marker has aided in identification and reorganization of zoanthids species, genera and families (Reimer et al. 2006a, 2006b, 2006c, 2007; Reimer and Todd 2009; Sinniger and Haussermann 2009; Sinniger et al. 2010; Swain 2009).

Coral reefs in the Persian Gulf are part of the complex and unique inter-tidal and sub-tidal habitats. Due to isolation from the open ocean, the Persian Gulf experiences extreme environmental conditions. It is one of the warmest and the most saline waters on earth and this has imposed a harsh condition on the marine organisms (Coles and Fadlallah 1991; Reynolds 1993) and as a result, a particular and unique marine fauna has evolved in this environment. In the northern Persian Gulf, there are 17 islands off the Iranian coastline with fringing coral reefs (Sheppard and Sheppard 1991). Although coral reef communities have been described at most of the Persian Gulf Islands (Fatemi and Shokri 2001; Namin and Van Ofwegen 2009; Rezai et al. 2010; Kavousi et al. 2011; Mostafavi et al. 2007; 2013; Samiei et al. 2013), there are no data on zoanthids in this area.

The purpose of this study was morphological observation and molecular identification of shallow water zoanthids off Qeshm Island. Upon collection, zoanthid specimens were grouped based on their external appearance. Then all the grouped species were molecularly identified. In this paper chromatic variability of all the collected specimens were provided and the accuracy of initial morphological identification was discussed.

Methods

Sample collection and preliminary identification

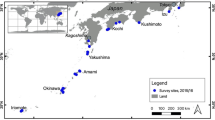

Twenty-six colonies of zoanthids were photographed and collected between December 2011 and March 2013 by wading or SCUBA diving in the inter-tidal zones of seven locations off Qeshm Island (Fig. 1).

Depth of sampling is shown in Table 1. Specimens were stored in 100 % ethanol at −20 °C. Initial identification was carried out based on in situ photographs (Fig. 2) with the support of published literature (Burnett et al. 1997; Ryland and Lancaster 2003; Reimer 2007; Reimer et al. 2006a).

In situ images of zoanthid specimens collected in this study. Each image is representative of one morphological group listed in Table 2

DNA extraction, PCR amplification and sequencing

Zoanthid fragments were crushed in DNAB (0.4 M NaCl, 50 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) buffer and then DNA was extracted using the CTAB-chloroform method (Baker 1999). Mitochondrial 16S rDNA was PCR amplified using zoanthid-specific primers 16Sant1a and 16SbmoH (Sinniger et al. 2005) with the following thermal cycle conditions: 2 min at 94 °C then 35 cycles: 30 s at 94 °C, 1 min at 52 °C, 90 s at 72 °C, followed by 7 min final extension at 72 °C. The amplified products were analyzed by 1.5 % agarose gel electrophoresis. Original PCR products from zoanthids specimens were sent to the Macrogen Company in South Korea and directly sequenced with ABI-3730XL analyzer by the capillary system method.

Phylogenetic analysis

Sequences obtained from this study were deposited in GenBank and their accession numbers are shown in Table 1. The nucleotide sequences obtained in this study were aligned with 16S rDNA sequences available from Genbank (accession numbers are shown in Fig. 3) using the software CLUSTALW (Thompson et al. 1994). The outgroup sequence for 16S rDNA tree was Parazoanthus gracilis.

The alignment dataset was analyzed using maximum likelihood (ML), maximum parsimony (MP) and Bayesian methods. The most appropriate model selection for ML and Bayesian analyses was performed using Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) in MODELTEST 2.3 (Nylander 2004). The general time-reversible model (Rodrigues et al. 1990) with invariable sites (GTR + I) gave the best fit to the 16S rDNA data. ML and MP analyses were conducted using the PAUP beta version 4.0b10 (Swofford 2003). For ML, a heuristic search was carried out with 100 random additions of taxa, followed by tree-bisection-reconnection (TBR) branch-swapping rearrangements with a maximum of 100 optimal trees kept in each replicate. Maximum likelihood clade support was assessed by nonparametric bootstrapping with 1,000 replicates and the same heuristic-search parameters. The MP analysis, also carried out by the heuristic-search method, consisted of 100 runs of stepwise random taxon additions. MP clades were assessed with 1,000 bootstrap replicates (excluding uninformative characters), with 100 random additions of taxa for each replicate.

The Bayesian analysis was implemented in MrBayes 2.3 (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck 2003) and was based on the model selected by MODELTEST above. Starting from random trees, four Markov chains (with one cold and three heated chains) were run simultaneously to sample trees using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) principle which approximates the posterior probability (PP) of trees. After the burn-in phase (the first 5 million generations was discarded), every 100th tree out of 206 was considered. The phylogenetic trees generated in all analyses were visualized using TREEVIEW (Page 1996).

Results

Morphological preliminary observation

The 26 collected zoanthid specimens were first divided into three morphological groups. Fourteen specimens were identified as belonging to the genus Palythoa due to their heavy sand encrustation, external brown or cream coloration (Table 2; Fig. 2) and the tentacle numbers which were almost fit with the numbers reported from Palythoa species of Indian and Pacific Ocean (Herberts 1972; Ryland and Lancaster 2003). Of these, four specimens (QeSu2, QeSu6, QeAu3 and QeAu6) were distinguished as Palythoa tuberculosa by their densely packed immersae polyps, ranging from almost light to dark brown. The other ten specimens were identified as Palythoa mutuki based on their elongated, cylindrical polyps with underdeveloped coenchyme (liberae polyps) and green or brown oral disk coloration. These polyps were joined basally, but their closeness and flaring columns obscured the bases (Fig. 2). The remaining morphological group (Table 2) contained 12 specimens which were clearly from the genus Zoanthus, as they had smooth, non-encrusted, liberae polyps. Since during the present study only chromatic variability of each specimen was monitored, species-level assignment was mostly impossible and they were just identifiable at the genus level. All morphological characters of each specimen (sand encrustation, polyp shape and color, oral groove, oral zone and oral disk colors, tentacle number and color) are summarized in Table 2.

Molecular-based Identification

Based on mitochondrial 16S ribosomal DNA, the zoanthids in this study were divided into two genus-level clades: Zoanthus and Palythoa. As shown in Fig. 3, all Zoanthus specimens belonged to the Zoanthus sansibaricus clade with a very well supported bootstrap (ML = 92 %, MP = 94 %, PP = 98 %).

The genus Palythoa was moderately supported (ML = 87 %, MP = 86 %, PP = 56 %). The sequences from specimens QeAu3, QeAu6, QeSu2 and QeSu6 were identical to AB219218 and DQ997860 from Palythoa tuberculosa and were within a moderately supported subclade (ML = 67 %, MP = 61 %, PP = 98 %). The ten sequences from specimens in the Palythoa mutuki morphological group differ from Palythoa mutuki 1 (DQ997860) and Palythoa mutuki 2 (DQ997841) in two and three base pairs, respectively. These sequences formed a moderately supported subclade (ML = 84 %, MP = 88 %, PP = 56 %) which was basal to Palythoa mutuki and Palythoa tuberculosa sequences.

Discussion

Utility of external morphological characteristics and molecular identification of zoanthids

In comparing morphological versus molecular identification results, we demonstrated that zoanthid identification based on the 16S ribosomal mitochondrial DNA marker is more accurate than using morphological characteristics. This is especially so when species with polymorphic characteristics are dealt with that is not consistently reliable.

During the preliminary identification process, all specimens were identified to the generic level using only external morphological criteria, but their species-level assignment were not possible or correct in most cases. The identification of Palythoa mutuki specimens remained somewhat ambiguous. Although morphologically, these specimens perfectly agreed with Palythoa mutuki, the mt 16S rDNA data presented unexpected two or three base pair of differences with Palythoa mutuki. While the mitochondrial markers are very conservative in anthozoans (Shearer et al. 2002), this low level of variation has previously indicated species-level differences in Palythoa species. For example, Palythoa mutuki and Palythoa tuberculosa can be distinguished by one base pair of difference over mt 16S rDNA data set. Therefore, with examination of only one marker, for now we designated these specimens as Palythoa cf. mutuki.

As mt 16S rDNA are considered to be one of the mitochondrial markers which are able to correctly place zoanthid specimens, especially for Zoanthidae and Spheopidae families, within a species group (Sinniger et al. 2008; Reimer and Todd 2009; Swain 2009), applying this marker in the present study categorized these specimens into three species-level groups with a high level of confidence.

Zoanthid diversity in the Persian Gulf

All specimens during the present study have been categorized into three different species groups: Zoanthus sansibaricus from Zoanthidae family, Palythoa tuberculosa and Palythoa cf. mutuki from Sphenopidae family. Of these three species, two are identified species which have been widely distributed in the western and eastern Pacific Ocean; i.e., Great Barrier Reef (Burnett et al. 1997; Ryland and Lancaster 2003), New Caledonia (Sinniger 2006), Japan (Reimer et al. 2004, 2006a, 2011; Reimer 2007), Galapagos (Reimer et al. 2008), Singapore (Reimer and Todd 2009) and Indian Ocean (Herberts 1972), while the remaining species, Palythoa cf. mutuki did not molecularly match with any of the previously reported sequences.

As mentioned earlier in this study, there is an overall lack of data on zoanthids from the Persian Gulf. Thus, it is somewhat difficult to assess if the Palythoa cf. mutuki is an endemic species, that was previously undescribed, or range extensions of species from other regions.

The Gulf is linked to the open ocean by the narrow Strait of Hormuz which limits water exchanges (Wilson et al. 2002). The three zoanthid species, Zoanthus sansibaricus, Palythoa tuberculosa and Palythoa mutuki seem to be very widespread in the Indo-Pacific, and they have been found in isolated locations like Ogasawara (Reimer et al. 2011) and Galapagos (Reimer et al. 2008) Islands. It has been demonstrated that Palythoa tuberculosa has a larval stage of over 2 weeks (Polak et al. 2011; Hirose et al. 2011). However, there are few data on the length of time of larval stages for zoanthid species in this study aside from Palythoa tuberculosa. We hypothesized that many of the zoanthids that are found in the Persian Gulf may have extended larval stages which have been reached and colonized as the first species in the relatively isolated Persian Gulf from the wider Indian Ocean.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the presence of at least two families, two genera and three species of zoanthids in the Persian Gulf. Furthermore, based on these observations, the presence of a potential new species was demonstrated. Most importantly, the results of this study indicated a need for further sampling and investigation of zoanthid from more regions to help complete the knowledge of zoanthid diversity in this area.

References

Baker AC (1999) The symbiosis ecology of reef-building corals. PhD Thesis, University of Miami

Burnett W, Benzie J, Beardmore J, Ryland J (1994) High genetic variability and patchiness in a common great barrier reef zoanthid (Palythoa caesia). Mar Biol 121:153–160

Burnett W, Benzie J, Beardmore J, Ryland J (1995) Patterns of genetic subdivision in populations of a clonal cnidarian, Zoanthus coppingeri, from the great barrier reef. Mar Biol 122:665–673

Burnett W, Benzie J, Beardmore J, Ryland J (1997) Zoanthids (Anthozoa, Hexacorallia) from the great barrier reef and Torres Strait, Australia: systematics, evolution and a key to species. Coral Reefs 16:55–68

Coles SL, Fadlallah YH (1991) Reef coral survival and mortality at low temperatures in the Arabian Gulf: new species-specific lower temperature limits. Coral Reefs 9:231–237

Fatemi SMR, Shokri MR (2001) Iranian coral reefs status with particular reference to Kish Island, Persian Gulf. In: Proceedings of international coral reef initiative (ICRI) regional workshop for the Indian Ocean, Maputo, Mozambique

Haddon AC, Shackleton AM (1891) A revision of the British Actiniae, part 2. The Zoanthae. Sci Trans R Dublin Soc 4:609–672

Herberts C (1972) Etude syste´matique de quelques zoanthaires tempe´re´s et tropicaux. Tethys Supp 3:69–156

Hirose M, Obuchi M, Hirose E, Reimer JD (2011) Timing of spawning and early development of Palythoa tuberculosa (Anthozoa, Zoantharia, Sphenopidae) in Okinawa, Japan. Biol Bulletin 220:23–31

Kavousi J, Seyfabadi J, Rezai H, Fnnner D (2011) Coral reefs and communities of Qeshm Island, the Persian Gulf. Zool Stud 50:276–283

Mostafavi PG, Fatemi MR, Shahhoseiny MH, Hoegh-Guldberg O, Loh WKW (2007) Predominamce of clade D Symbiodinium shallow water reef- building corals off Kish and Larak Islands (Persian Gulf, Iran). Mar Biol 153:25–34

Mostafavi PG, Ghayem Ashrafi M, Dehghani H (2013) Are symbiotic algae in corals in northern parts of the Persian Gulf resistant to thermal stress? Aquat Ecosyst Health Manage 16:177–182

Namin KS, Van Ofwegen L (2009) Some shallow water octocorals (Coelenterata:Anthozoa) of the Persian Gulf. Zootaxa 2058:1–52

Nylander J (2004) MrModeltest v2. Uppsala University, Program distributed by the author. Evolutionary Biology Centre

Page RDM (1996) TREEVIEW: an application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput App Biosci 12:357–358

Polak O, Loya Y, Brickner I, Kramarski-Winter E, Benayahu Y (2011) The widely-distributed Indo-Pacific zoanthid Palythoa tuberculosa: a sexually conservative strategist. Bull Mar Sci 87:605–621

Reimer JD (2007) Preliminary survey of zooxanthellate zoanthid diversity (Hexacorallia:Zoantharia) from southern Shikoku, Japan. Kuroshio Biosphere 3:1–16

Reimer JD, Fujii T (2010) Four new species and one new genus of zoanthids (Cnidaria:Hexacorallia) from the Galapagos. ZooKeys 42:1–36

Reimer JD, Todd PA (2009) Preliminary molecular examination of zooxanthellate zoanthid (Hexacorallia, Zoantharia) and associated zooxanthellae (Symbiodinium spp.) diversity in Singapore. Raffles Bulletin Zool 22:103–120

Reimer JD, Ono S, Fujiwara Y, Takishita K, Tsukahara J (2004) Reconsidering Zoanthus spp. diversity: molecular evidence of conspecifity within four previously presumed species. Zoolog Sci 21:517–525

Reimer JD, Ono S, Iwama A, Takishita K, Tsukahara J, Maruyama T (2006a) Morphological and molecular revision of Zoanthus (Anthozoa:Hexacorallia) from southwestern Japan, with descriptions of two new species. Zoolog Sci 23:261–275

Reimer JD, Ono S, Iwama A, Tsukahara J, Maruyama T (2006b) High levels of morphological variation despite close genetic relatedness between Zoanthus aff. vietnamensis and Zoanthus kuroshio (Anthozoa:Hexacorallia). Zoolog Sci 23:755–761

Reimer JD, Ono S, Takishita K, Tsukahara J, Maruyama T (2006c) Molecular evidence suggesting species in the zoanthid genera Palythoa and Protopalythoa (Anthozoa:Hexacorallia) are congeneric. Zoolog Sci 23:87–94

Reimer JD, Sinniger F, Fujiwara Y, Hirano S, Maruyama T (2007) Morphological and molecular characterisation of Abyssoanthus nankaiensis, a new family, new genus and new species of deep-sea zoanthid (Anthozoa:Hexacorallia:Zoantharia) from a north-west Pacific methane cold seep. Invertebr Systematics 21:255–262

Reimer JD, Sinniger F, Hickman JRC (2008) Zoanthid diversity (Anthozoa:Hexacorallia) in the Galapagos Islands: a molecular examination. Coral Reefs 27:641–654

Reimer JD, Nakachi S, Hirose M, Hirose E, Hashiguchi S (2010) Using hydrofluoric acid for morphological investigations of zoanthids (Cnidaria: anthozoa): a critical assessment of methodology and necessity. Mar Biotechnol 12:605–617

Reimer JD, Hirose M, Yanagi K, Sinniger F (2011) Marine invertebrate diversity in the oceanic Ogasawara Islands: a molecular examination of zoanthids (Anthozoa:Hexacorallia) and their Symbiodinium (Dinophyceae). Syst Biodivers 9:133–143

Reynolds MR (1993) Physical oceanography of the Gulf, Strait of Hormuz, and the Gulf of Oman-results from the Mt Mitchell expedition. Mar Pollut Bull 27:35–59

Rezai H, Samimi K, Kabiri K, Kamrani E, Jalili M, Mokhtari M (2010) Distribution and abundance of the corals around Hengam and Farurgan islands, the Persian Gulf. J Persian Gulf 1:7–16

Rodrigues F, Oliver J, Marin A, Medina JR (1990) The general stochastic model of nucleotide substitution. J Theor Biol 142:485–501

Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP (2003) MrBayes 3: bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19:1572–1574

Ryland JS, Lancaster JE (2003) Revision of methods for separating species of Protopalythoa (Hexacorallia:Zoanthidea) in the tropical West Pacific. Invertebr Systematics 17:407–428

Samiei JV, Dab K, Ghezellou P, Shirvani A (2013) Some scleractinian corals (Scleractinia:Anthozoa) of Larak Island, Persian Gulf. Zootaxa 3636:101–143

Shearer T, Van oppen M, Romano S, Worheide G (2002) Slow mitochondrial DNA sequence evolution in the Anthozoa (Cnidaria). Mol Ecol 11:2475–2487

Sheppard CR, Sheppard AS (1991) Corals and coral communities of Arabia. Fauna Saudi Arab 12:3–170

Sinniger F (2006) Zoantharia of New Caledonia. In: Compendium of marine species from New Caledonia. C. Payri and B. Richer de Forges, eds. Documents scientifiques et techniques II 7:127–128

Sinniger F, Haussermann V (2009) Zoanthids (Cnidaria:Hexacorallia:Zoantharia) from shallow waters of the southern Chilean fjord region, with descriptions of a new genus and two new species. Org Divers Evol 9:23–36

Sinniger F, Montoya-Burgos J, Chevaldonne P, Pawlowski J (2005) Phylogeny of the order Zoantharia (Anthozoa, Hexacorallia) based on the mitochondrial ribosomal genes. Mar Biol 147:1121–1128

Sinniger F, Reimer JD, Pawlowski J (2008) Potential of DNA sequences to identify zoanthids (Cnidaria:Zoantharia). Zoolog Sci 25:1253–1260

Sinniger F, Reimer JD, Pawlowski J (2010) The Parazoanthidae (Hexacorallia:Zoantharia) DNA taxonomy: description of two new genera. Marine Biodivers 40:57–70

Swain TD (2009) Phylogeny-based species delimitations and the evolution of host associations in symbiotic zoanthids (Anthozoa, Zoanthidea) of the wider Caribbean region. Zool J Linnean Soc 156:223–238

Swofford D (2003) PAUP*: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony, version 4.0 b10. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland

Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ (1994) CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 22:4673–4680

Wilson S, Fatemi SMR, Shokri MR, Claereboudt M (2002) Status of coral reefs of the Persian/Arabian Gulf and Arabian Sea region. Status of coral reefs of the world: 53–62

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Hamed Dehghani for collection assistance, Dr. Fredric Sinniger, Japanese Agent for Marine Science and Technology (JAMSTEC) for his useful advice and his answers to all questions during this study and Dr. James D. Reimer, university of Ryukyus, Japan, for his useful comments.

Conflict of interest

All authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Author contribution

ANK carried out sampling, the experimental and phylogenetic analysis and wrote the article. PGM participated in the study design, revised the written article and submitted it. JFM and SMF made the comments and discussed on the results. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Koupaei, A.N., Mostafavi, P.G., Mehrabadi, J.F. et al. Molecular diversity of coral reef-associated zoanthids off Qeshm Island, northern Persian Gulf. Int Aquat Res 6, 64 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40071-014-0064-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40071-014-0064-8