Abstract

Electrodeposition can be used in order to prepare nanocomposite coatings made of nanoparticles dispersed into a metallic matrix, onto a metallic substrate. These kinds of coatings can combine the properties of the matrix and of the dispersed nanoparticles, which can lead to some interesting properties of the mixture. Including diamond nanoparticles into a metallic matrix can take advantage of the diamond properties, especially of its hardness and inertness in many chemical media. Still, the proper control of the electrodeposition parameters is a must in order to obtain the best microhardness and corrosion behavior of such nanocomposite coating. This paper proposes the comparative analysis between Ni/diamond nanocomposite coatings, prepared by electrodeposition, by varying several deposition parameters and the corresponding pure nickel coatings onto the same type of substrate, namely copper. Microstructural and morphological analysis of the two kinds of coatings are also performed and studied, along with microhardness measurements and corrosion resistance tests. It is concluded that specific electrodeposition technique and corresponding parameters must be used in order to prepare those Ni/diamond nanocomposite coatings with the best microhardness and best corrosion resistance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The co-deposition of particles from an electrolytic bath can be used in order to obtain nanocomposite layers within a metallic matrix, which contains inert particles spread as disperse phases (Watson 1993; Suzuki and Asai 1987). Recently, this technique has captured the attention of scientists, considering its interesting possibilities, especially from the point of view of the size of the inert particles, such as: ceramics, polymers and metallic powders, which can reach sizes as small as micro- and even nanometers. The electrodeposition of inert powders implies the initial dipping of the electrode into the plating solution and then, the nanocomposite layers are obtained by applying an electrical current. The dispersed phases incorporated into the nanocomposite layers also include carbide powders, nitrites, boron compounds and ceramic oxides. The crystals sizes, the surface morphology, the preferential orientation and the thickness of the nickel electrodepositions depend both on the electrolysis conditions and on the composition of the electrolyte (Feldstein 1981; Kollia and Spyrellis 1993; Pushpavanam et al. 2007; Chandrasekar and Pushpavanam 2008).

Studies were reported concerning the preparation of diamond nanocomposites, which are already produced at industrial scale by means of controlled detonation, through the plasma jet process and/or by electro-explosive wires. These coatings can be used for various industrial purposes (Shen et al. 2009; Li et al. 2002, 2007). Moreover, the diamond nanoparticles included into the nickel matrix lead to fine polishing surfaces that can be used in dentistry (Sato et al. 1997). The various applications of such coatings are given by the unique properties of diamond, namely the high hardness, the low friction coefficient, the inertness to some acids and to the attack by other chemical substances (Feldstein and Lancsek 1984; Ranjan et al. 2010).

Experimental details

Pure Ni and Ni/diamond nanocomposite coatings were electrodeposited, according to the conditions given in Table 1. The electrodeposition of the nanocomposites was performed by using a Watts electrolyte, which is largely used in nickel electrodeposition solution (Subhash and Jitendra 2008).

The electrodeposition was done by means of an EG&G 263 A potentiostat/galvanostat, made in USA. Comparative experiments were performed between pure nickel electrodepositions and Ni/diamond nanocomposites in a Watts electrolyte, by employing either the direct current method or the pulse method.

The deposition conditions were chosen by carefully studying the similar works found in the scientific literature and by successive experimental trials, which allowed us to select such a combination of deposition parameters that would be expected to lead to diamond nanocomposite coatings with improved properties. Thus, the concentration of the diamond nanoparticles into the electrolyte was chosen as 5 g/l, as obtained by weighting. This value was also chosen according to Pushpavanam et al. (2007), is being lower than one used by Lee et al. (Ranjan et al. 2010). The diamond nanoparticles had sizes ranging from 70 nm till 80 nm and it were ultrasonically dispersed into the electrolyte for 10 min prior to the electrodeposition. The pH of the electrolyte was kept at 4.0 ± 0.5 [similarly to (Pushpavanam et al. 2007)], being adjusted with 98 % H2SO4 and 99.5 % NaHCO3. The electrolyte solution was mechanically stirred, with 250-300 rpm.

The working temperature was 50 ± 1 °C, being controlled by means of a GD1-type of Haake thermostat, with ±1 °C precision. As far as studied in the literature, lower working temperatures were used by other scientists in similar type of experiments [30 °C in (Pushpavanam et al. 2007) and 40 °C in (Ranjan et al. 2010)]. We used such a higher working temperature since at higher temperatures one would expect a more efficient crystal growth and lower stress of the crystalline grains.

Small copper plates embedded into a rigid holder, with 2.26 cm2 active surface were used as working electrode. The copper plates were vertically centered and they were surrounded by a cylinder-shape electrode, with opposite polarity, made of high-purity (99.99 %) nickel. The saturated calomel electrode (SCE) was used as reference. Prior to the experimental measurements, the copper substrate was mechanically polished with silicon carbide (SiC) abrasive paper, with several granulations (800, 1,200, 2,400 and 4,000 μm, respectively). Then, the polished copper substrate was electrochemically degreased at 3 V and 0.2 A/dm2, for 20–30 s, into an alkaline solution made of UNAR EL 63 (Schering, Germany). After this, the substrates were activated at room temperature into 1 N hydrochloric acid solution, followed by washing with bidistilled water and drying with air under pressure.

The diamond nanoparticles within the nanocomposite coatings obtained in nickel matrix were studied for their particular properties. Thus, the morphology, the hardness and the corrosion behavior of the nanocomposite coatings were studied. An X-ray diffractometer type DRON-3, with copper target, operating at the Kα line (λ = 1.5416 Å) was used for structural analysis, while the morphology was studied by means of a Quanta 200 scanning electron microscope (SEM). The EIS measurements were performed by using a VoltaLab 10 device, comprising a PGZ100 Potentiostat and a VoltaMaster 4 Electrochemical Software.

The influence of the particles

The diamond nanoparticles incorporated into nickel matrix used by electrodeposition had high purity (>96 %) and their distribution within the metallic matrix had a good uniformity.

Figure 1 presents the correlation between the incorporation percentage of the diamond nanoparticles into the Ni matrix obtained by direct current (D.C.) and by pulsed current as a function of the duty rates, θ. The selected frequencies, υ of the pulsed current (P.C.) are written in the inset of Fig. 1. From this figure, it can be concluded that the nanocomposite electrodepositions done by P.C. present a higher incorporation percentage into the Ni matrix as compared to the ones obtained by D.C. The highest incorporation percentage was obtained at θ = 10 % and at υ = 10 Hz. The data for the incorporation percentage of the nanoparticles into the Ni matrix through D.C. are presented in Fig. 1 at θ = 100 %.

Microstructural characteristics of the Ni/diamond nanocomposite coatings

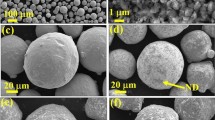

The investigation of the surface of the nanocomposite coatings, having a thickness up to 5 μm, represents the most important aspect when studying the metallic morphology. The morphology and structure of the Ni/diamond nanocomposite coatings were examined by means of scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and by X-ray diffraction (XRD), respectively. The SEM micrographs of the Ni/diamond nanocomposite coatings as compared to pure Ni coatings, with similar electrodeposition conditions, obtained for several current frequencies, υ and different duty cycles, θ are presented in Fig. 2. These images reveal important structural changes within the nanocomposite coatings as compared to the pure nickel coatings.

Both the structural analysis and the morphology investigation are useful both for showing the aspect of the surfaces of the nickel coatings as compared to the Ni/diamond nanocomposite coatings and also for checking the growing pattern of the electrodeposited crystals. Thus, the uniformity of the nanoparticles included into the nickel matrix is revealed.

The sizes of the grains vary with the deposition conditions. Thus, for P. C. depositions at θ = 20 % and υ = 0.01 Hz (see Fig. 2a), the grains range between 0.1 and 3 μm for pure Ni coatings, while they decrease to 0.1–1 μm for Ni/diamond nanocomposites. At θ = 50 % and υ = 0.1 Hz (see Fig. 2b), the biggest grains of pure Ni do not exceed 2 μm, while the Ni/diamond nanocomposite deposited in similar conditions present smaller grains, not surpassing 0.5 μm.

One can notice form the SEM images that the dispersion of the diamond nanoparticles was uniform, especially at those surfaces obtained at high frequency of the applied pulses of current: υ = 1 Hz (see Fig. 2c). This time, for pure Ni coatings, one can notice a predominance of big grains and fewer small grains, while the Ni/diamond nanocomposite deposited also at θ = 90 % and υ = 1 Hz have fragmented grains, reaching not more than 2 μm.

The coatings deposited by direct current present smaller grains (see Fig. 2d), in average than the coatings deposited by pulsed current. The pure Ni coating deposited by D. C. has a more uniform grain size distribution, while the Ni/diamond nanocomposite deposited by D. C. is similar to the one in Fig. 2a. Thus, as expected, after adding diamond to Ni, no more high grains are forming within the nanocomposites.

Most of the Ni/diamond nanocomposite electrodepositions, obtained in Watts electrolyte have a shining aspect. The morphology of the coatings obtained at lower current frequencies (0.01 and 0.1 Hz, respectively) exhibit differences as compared to the ones prepared at higher frequencies (1 and 10 Hz, respectively). Thus, the coatings with bigger crystals have a higher microhardness. At υ = 10 Hz, the lowest microhardness for θ = 90 % reaches 262 HV, while the highest microhardness for θ = 10 % is 459 HV. This aspect proves the expected correlation between microhardness and granulation. Figure 3 reveals the difference between the morphologies of each of the Ni/diamond discussed coatings, having extreme values of the microhardness, at υ = 10 Hz.

Figure 4 presents the XRD profiles for the P.C.-electrodeposited Ni/diamond coatings, at υ = 10 Hz and at constant current density of 5 A/dm2, for different duty cycles, θ. The relative intensities of the XRD peaks are those who are plotted, but they are now showed because of the waterfall-type of overlapped representation of multiple XRD patterns. Table 2 resumes the precise values of the relative intensities of the XRD peaks from all the graphs in Fig. 3. The crystalline planes are presented only for Nickel, the other peaks being merely assigned to the other chemical elements displaying XRD peaks (diamond—C and Copper—Cu).

From the XRD analysis, it can be inferred that the studied nanocomposite coatings have a face-centered cubic structure, with different orientations, which where influenced by the values of the P. C. duty cycles. Thus, if for θ = 10 and 20 %, respectively, the highest peaks is asserted to the (200) planes, instead, for higher θ, namely for 50 and 90 %, respectively, the highest peak is associated to the (111) planes. The other XRD peaks are also changing from one set of deposition conditions to another. Thus, the (220) peak varies from 4.76 for θ = 10 to 16.67 % for θ = 50 %. Instead, the peak asserted to the (311) plane stays almost the same for θ = 10, 20 and 50 %, respectively, but for 90 % jumps at a very high value, of 76.47 arb. units. The (222) peak does really change with changing deposition conditions.

Thus, a change of the intensity of the XRD peaks corresponding to nickel can be noticed when the duty cycle increases. When the duty cycle deposition parameter is changed to higher values (10 Hz), this gives rise to a decrease of the peak (200) in favor to the (111) peak and to an increase of (311) to (111) surface orientations ratio. This aspect is an indication of the grain refinement with increasing duty cycle.

Still, it remains to be established how the deposition frequencies of 0.01 and 10 Hz, respectively, for different duty cycles, influence the uniform particle distribution or if nucleation and subsequent aggregation of incorporated diamond particles alter the pure Ni matrix grain size and preferred surface orientations during its growth as a function of P.C. parameters and kinetics of each process (diamond adsorption and Ni plating).

Figure 5 reveals the influence of some deposition parameters, such as: current frequency and duty cycle on the microhardness of the Ni/diamond nanocomposites as compared to pure Ni coatings, prepared at constant current density of 5 A/dm2.

The microhardness measurements revealed values between 210 and 334 HV for the pure nickel electrodeposited coatings, while for the Ni/diamond nanocomposites values between 262.61 and 459.21 HV were obtained. Increases and decreases of the microhardness were noticed for the studied coatings with changing pulse frequency. The standard deviation of the measurements were ±10–38 HV for the pure Ni coatings and ±21–47 HV for the Ni/diamond nanocomposite coatings.

As noticed from the SEM images, the pure Ni coatings present larger grains than the Ni/diamond nanocomposites. The decrease of Ni grains surfaces due to diamond addition leads to an increase of the microhardness of the Ni/diamond nanocomposites as compared to the pure Ni ones. Also, the presence of the diamond powder itself is a cause of microhardness increase.

The crystallites growth is influenced by the frequency of the electrodes polarity changes during the depositions, such that the microstructure changes with frequency and, thus, the microhardness also changes.

Corrosion behavior

Potentiodynamic polarization tests

Corrosion studies were performed on the Ni/diamond nanocomposite coatings as compared to the pure Ni coatings, electrodeposited from Watts electrolyte. Two methods were employed: (1). the potentiodynamic polarization curves (LP); (2). The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), by using 0.5 M Na2SO4 testing solution, with pH 2. Monitoring the corrosion potential of each sample was performed first. For the potentiodynamic polarization measurements, the initial potential were −0.5 V (SCE), while the final potential was 0.1 V, with 10 mV/s scanning speed. The values of the polarization resistance were obtained from the impedance diagrams performed at the corrosion potential for each sample. The diagrams of the potentiodynamic polarization curves of the studied coatings, obtained for 30 min and for 60 min immersion times, respectively are presented in Figs. 6, 7, 8 and the corresponding corrosion current, icor, polarization resistance, Rp and the Tafel constants, βa and βc are given in Tables 3 and 4. The corrosion diagrams are not represented with the same potential intervals on the horizontal axis, because of the differences between the potential where each analyzed coatings presents points of extreme for these kinds of dependences (log I versus E).

The potential of the current varies with increasing current frequency and duty cycle into the active area. The curves reveal a passive behavior between approximately −0.3 and 0.0 V for the depositions performed at different duty cycles, but with the same value for the current density, of 5 A/dm2. The best corrosion resistance, of 20.3 \(k\varOmega \,cm^{2}\) was obtained for υ = 10 Hz, θ = 20 %, for 1 h immersion time into the testing solution. Thus, independently of the changes in the corrosion potential with pulse frequency and duty cycle, the experimental results are ascribed to the potential range from −0.3 to 0.0 V.

The corrosion resistance of the nanocomposite coatings is influenced both by the preparation of the electrodeposited Ni matrices and also by the incorporation of the diamond nanoparticles. It was reported that while the reverse ratio and the pulse frequency increased, more crystal nuclei were formed into the electrodeposited Ni coatings and that their granulation became smaller Lee et al. 1999. Wang et al., established that the corrosion resistance was improved by a decrease of the grain size onto the coating, since into finer grain coating the passivation was better (Lee et al. 1999).

For the Ni/diamond nanocomposite electrodepositions, the Ecor potential is displaced to more negative values than for pure nickel, which indicates an activation of those coatings in strong acid environment (see Fig. 8).

Analysis by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS)

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy was also used for the analysis of the electrodeposited coatings, in order to have another representation of the corrosion behavior.

Differences between the polarization curves were noticed with increasing deposition duration. Almost each of the polarization curves presented a minimum, indicating the value of the polarization resistance. The Nyquist diagrams of the EIS spectra are presented in Fig. 9, for pulse current Ni/diamond nanocomposite coatings, electrodeposited for 1 h into the Watts nickel electrolyte, corresponding to 10 min, 1, 2, 4, 6, 24 and 30 h immersion time into 0.5 M Na2SO4 solution with pH 2.

By analyzing Fig. 9 one can notice that a 10 times increase in the frequency of the deposition leads to a drastic decrease, by four times, of the imaginary value Z″ of the impedance and to a more than 2 times decrease of the real values Z′ of the impedance. Also, the immersion time strongly influences the aspect of the Nyquist diagrams. Thus, for υ = 0.01 Hz, the graphs for 4 and for 6 h of immersion into the Na2SO4 solution do not close to the horizontal axis, while the one reaching the fastest this axis corresponds to 30 h immersion time. Instead, for υ = 0.1 Hz, all the curves reach the horizontal axis, finally, the quickest corresponding to 2 h immersion time and the longest appearing for the coating which was immersed for 6 h.

Figure 10 presents the Nyquist diagrams for the pure nickel coatings (Fig. 10a) and for Ni/diamond nanocomposite coatings (Fig. 10b), prepared by direct current electrodeposition, corresponding to 10 min, 1, 2, 4, 6, 24 and 30 h immersion time into 0.5 M Na2SO4 solution with pH 2.

While the aspect of the Nyquist diagrams is irregular for pure Ni coatings, this is not the case for Ni/diamond nanocomposite coatings. Still, shorter the immersion time, higher the maximum reached values of Z′ for the Ni/diamond nanocomposites.

It was noticed that both the Ni/diamond nanocomposite coatings and the pure nickel coatings presented a polarization resistance which decreased after 30 h of investigation. The corrosion potential was Ecor = −0.21 V and changed in time to more positive values. This behavior indicates an active dissolving with reduction of the oxidant (H+).

As a reminder, the polarization resistance technique (sometimes referred to as linear polarization) is an experimental electrochemical technique that enables the estimation of the polarization resistance and from that the corrosion rate. The experiment requires polarizing an electrode between about −20 mV and +20 mV relative to the steady state corrosion potential. Some authors refer to the polarization resistance and to the capacitance terms as charge transfer resistance (RCT) and pseudo-capacitance.

Figure 11 presents the equivalent circuit for the Ni/diamond nanocomposite coatings, where the notations correspond to: Re = the resistance of the electrolyte, measured between the working electrode and the reference electrode; Rp is the polarization resistance or the resistance transfer at the Ni/Na2SO4 interface; CPE is a constant phase element.

The charge transfer resistance determined by using the equivalent circuit model given in Fig. 11 should be taken as an overall or effective polarization resistance of the electrode. Effect of the electrode resistivity on the performance of the porous CEs is a subject of ongoing research (Haseko et al. 2006).

Figures 12 and 13 present the values of the polarization resistance, Rp and those of the capacitance computed with the equivalent circuit from Fig. 11, for the Ni/diamond nanocomposite coatings, P.C. and D.C. electrodeposited, respectively, for 3,600 s in Watts electrolyte, after different immersion duration into 0.5 M Na2SO4 solution, for all the tested electrodeposition conditions (υ = 0.01, 0.1, 1 and 10 Hz, respectively).

The variation of the polarization resistance, Rp for the Ni/diamond nanocomposite coatings, P.C. and D.C. electrodeposited, respectively, for 3,600 s in Watts electrolyte, after different immersion duration into 0.5 M Na2SO4 solution, for all the tested electrodeposition conditions (υ = 0.01, 0.1, 1 and 10 Hz, respectively)

The variation of the capacitance (constant phase element), CPE for the Ni/diamond nanocomposite coatings, P.C. and D.C. electrodeposited, respectively, for 3,600 s in Watts electrolyte, after different immersion duration into 0.5 M Na2SO4 solution, for all the tested electrodeposition conditions (υ = 0.01, 0.1, 1 and 10 Hz, respectively)

The CPE parameter can be used to infer the surface roughness (Halme et al. 2006), but the present study didn’t propose for roughness estimations in this phase of the analysis. Still, there are some other factors influencing the CPR: surface reactivity, surface inhomogeneity, electrode porosity, etc. (Jorcin et al. 2006).

It can be noticed that the polarization resistance of the Ni/diamond nanocomposites had a smaller value than that of the pure nickel coating. The capacity of the double electric layer was around 19.40 μF/cm2, which is somewhat smaller than that of pure nickel coating. The corrosion potential was driven to more negative values than pure electrodeposited nickel, having an average polarization resistance of 6.3 kΩ cm2, but with a better stability as compared to the nanocomposite coatings. The values of the polarization resistance computed from the potentiodynamic diagrams, by using Stern-Geary formula are closer to the ones obtained from the electrochemical impedance Spectroscopy measurements.

The polarization resistance of the Ni/diamond nanocomposite coatings presents the highest value of 60.00 kΩ cm2, after 30 h of immersion into the Na2SO4 solution, for the samples electrodeposited at υ = 0.01 Hz and θ = 20 %. The smallest value for the polarization resistance, namely 2.79 kΩ cm2 was measured for the Ni/diamond nanocomposite coating electrodeposited at υ = 1 Hz and θ = 90 %, also after 30 h of immersion into the Na2SO4 solution.

The D.C. electrodeposition of/diamond nanocomposite led to somewhat smaller values for Rp, not exceeding 30 kΩ cm2, values which are smaller than for pure Ni coatings.

As about the CPE, Fig. 13 reveals that it surpasses 300 μF/cm2 for the nanocomposite coating P.C. deposited at the highest frequency, υ = 10 Hz and for 20 % duty cycle. As for the D.C. electrodepositions, the pure Ni coatings present somewhat smaller values for CPE than the corresponding Ni/diamond nanocomposites.

From the obtained results one cannot make a complex evaluation of the kinetic reactions that take place and no unitary mechanism can be considered for the composite system. Vaster studies are needed. The nanocomposite system differentiates both by its forming mechanism and by its corrosion behavior in the studied electrolyte. The electrodeposition of the diamond nanoparticles into nickel matrix improves the corrosion behavior of the coatings. The obtained results are encouraging and suggest that the diamond nanoparticles coating can represent an attractive alternative for the protection of surfaces by introducing a barrier between the aggressive medium and the metallic substrate.

Conclusions

Ni/diamond nanocomposite coatings and pure Ni coatings were prepared by P.C. and D.C. electrodeposition onto copper substrates, with several values for the pulses frequencies and for different necessary durations. It was found out that the diamond nanoparticles content increases with increasing pulse frequency and decreasing duty cycle. The experimental results proved that the microhardness and the roughness of the Ni/diamond nanocomposite coatings were strongly influenced by the presence of the nanoparticles as compared to pure nickel coatings. By using the pulse current electrodeposition instead of direct current electrodeposition, the microhardness of the nanocomposite coatings increased, especially for low duty cycles and low current frequency. The corrosion behavior of the studied coatings represents a priority for the properties of new materials. Modern methods were employed for the study of the corrosion behavior, namely the potentiodynamic polarization curves and the electrochemical impedance spectra. These methods offer very useful information about the kinetics of the chemical reactions at the electrode. The corrosion studies in strongly corrosive electrolyte (0.5 M Na2SO4 solution, with pH 2) have revealed a better behavior of the Ni/diamond nanocomposite coatings as compared to the pure nickel coatings. Also, it was concluded that the corrosion resistance of the nanocomposite coatings increased with decreasing pulse frequency and reverse ratio. The best corrosion resistance \(R_{p} = \, 20.3\,k\varOmega \,cm^{2}\), was obtained for the nanocomposite coatings prepared in the following conditions: υ = 10 Hz, θ = 20 %, for 1 h of immersion into the testing solution. More complex studies are necessary in order to elucidate the phenomena and the kinetic reactions, such that the anticorrosive protection mechanism would be better understood and also its influence factors would be inferred for the Ni/diamond nanocomposite coatings.

References

Chandrasekar MS, Pushpavanam M (2008) Electrochim Acta 53:3313–3322

Feldstein N (1981) Composite coatings. Materials Engineering, Cleveland

Feldstein N, Lancsek T (1984) J Electrochem Soc 131(12):3026–3027

Halme J, Toivola M, Tolvanen A, Lund P (2006) Sol Energ Mat Sol C 90(78):872886

Haseko Y, Shrestha NK, Teruyama S, Saji T (2006) Electrochim Acta 51(18):3652–3657

Jorcin JB, Orazem ME, Pebere N, Tribollet B (2006) Electrochim Acta 51:1473–1479

Kollia C, Spyrellis N (1993) Surf Coat Tech 57:101–105

Lee WH, Tang SC, Chung KC (1999) Surf Coat Tech 120–121:607–611

Li YD, Li GS, Jiang H, He YP (2002) Ind Diam Rev 62:259–262

Li YD, Jiang H, Pang L, Wang B (2007) Surf Coat Tech 201(12):5925–5930

Pushpavanam M, Manikandan H, Ramanathan K (2007) Surf Coat Tech 201(14):6372–6379

Ranjan S, Ashutosh S, Sumit B, Siddhartha D, Karabi D (2010) J Nanosci Nanotechnol 10:4998–5003

Sato K, Suzuki K, Yokoyama T, Kagawa H (1997) Mater J Proc Tech 63:829–832

Shen B, Sun FH, Zhang ZM (2009) J Nanosci Nanotechnol 9:788–792

Subhash T, Jitendra K (2008) J Nanosci Nanotechnol 8:4073–4080

Suzuki Y, Asai O (1987) J Electrochem Soc 134:1905–1910

Watson SW (1993) J Electrochem Soc 140(8):2235–2238

Acknowledgments

The research of this paper has been supported by POSDRU/88/1.5/S/61445 Project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Gheorghies, C., Rusu, D.E., Bund, A. et al. Synthesis and characterization of nickel–diamond nanocomposite layers. Appl Nanosci 4, 1021–1033 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13204-013-0285-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13204-013-0285-y