Abstract

We introduce anisotropy continuation as a process which relates changes in seismic images to perturbations in the anisotropic medium parameters. This process is constrained by two kinematic equations, one for perturbations in the normal-moveout (NMO) velocity and the other for perturbations in the dimensionless anisotropy parameter η. We consider separately the case of post-stack migration and show that the kinematic equations in this case can be solved explicitly by converting them to ordinary differential equations using the method of characteristics. When comparing the results of kinematic analytical computations with synthetic numerical experiments confirms the theoretical accuracy of the method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A well-known paradox in seismic imaging is that the detailed information about the subsurface velocity is required before a reliable image can be obtained. In practice, this paradox leads to an iterative approach to building the image. It looks attractive to relate small changes in velocity parameters to inexpensive operators perturbing the image. This approach has been long known as residual migration. A classic result is the theory of residual post-stack migration (Rothman et. al. 1985), extended to the prestack case by Etgen (1990). In a relatively recent paper, Fomel (1996) introduced the concept of velocity continuation as the continuous model of the residual migration process. All these results were based on the assumption of the isotropic velocity model.

Recently, emphasis has been put on the importance of considering anisotropy and its influence on data. Alkhalifah and Tsvankin (1995) demonstrated that, for TI media with vertical symmetry axis (VTI media) and mild lateral inhomogeneity, just two parameters are sufficient for performing all time-related processing, such as normal moveout (NMO) correction (including non-hyperbolic moveout correction, if necessary), dip-moveout (DMO) correction, and prestack and poststack time migration in a homogeneous medium. One of these two parameters, the short-spread NMO velocity for a horizontal reflector, is given by

where vv is the vertical P-wave velocity, and δ is one of Thomsen’s anisotropy parameters (Thomsen 1986). Taking vh to be the P-wave velocity in the horizontal direction, the other anisotropy parameter, η, is given by

where \(\epsilon\) is another of Thomsen’s parameters. In addition, Alkhalifah (1998) has showed that the dependency on just two parameters becomes exact when the vertical shear wave velocity (VS0) is set to zero. Setting VS0 = 0 leads to remarkably accurate kinematic representations. It also results in much simpler equations that describe P-wave propagation in VTI media. Throughout this paper, we use these simplified, yet accurate with respect to conventional data processing objectives, equations, based on setting VS0 = 0, to derive the continuation equations. Because we are only considering time sections, and for the sake of simplicity, we denote vnmo by v. Thus, time processing in VTI media, depends on two parameters (v and η), whereas in isotropic media only v counts. To emphasize the importance of anisotropy to the dip moveout process, Alkhalifah (2005) introduced residual dip moveout for VTI media.

In this paper, we generalize the velocity continuation concept to handle VTI media. We define anisotropy continuation as the process of seismic image perturbation when either v or η change as migration parameters. This approach is especially attractive, when the initial image is obtained with isotropic migration (that is with η = 0). In this case, anisotropy continuation is equivalent to introducing anisotropy in the model without the need for repeating the migration step.

For the sake of simplicity, we start from the post-stack case and purely kinematic description. We define, however, the guidelines for moving to the more complicated and interesting cases of prestack migration and dynamic equations. The results open promising opportunities for seismic data processing in the presence of anisotropy.

The general theory

In the case of zero-offset reflection in homogeneous media, the ray travel distance, l, from the source to the reflection point is related to the two-way zero-offset time, t, by the simple equation

where vg is the group velocity, best expressed in terms of its components, as follows:

Here v gx denotes the horizontal component of group velocity, vv is the vertical P-wave velocity, and v gτ is the vv-normalized vertical component of the group velocity. Under the assumption of zero shear-wave velocity in VTI media, these components have the following analytic expressions:

and

where p x is the horizontal component of slowness, and p τ is the normalized (again by the vertical P-wave velocity v v ) vertical component of slowness. The two components of the slowness vector are related by the following eikonal-type equation (Alkhalifah 1998):

Equation (6) corresponds to a normalized version of the dispersion relation in VTI media.

If we consider v and η as imaging parameters (migration velocity and migration anisotropy coefficient), the ray lengthl can be fixed through the imaging process. This implies that the partial derivatives of with respect to the imaging parameters are zero. Therefore,

and

Applying the simple chain rule to Eqs. (7) and (8), we obtain

where \(\frac{\partial t}{\partial \tau} = - p_{\tau}\), and the two-way vertical travel time is given by

Combining Eqs. (7–9) eliminates the two-way zero-offset time t, which leads to the equations

and

After some tedious algebraic manipulation, we can transform Eqs. (10) and (11) to the general form

and

Since the residual migration is applied to migrated data, with the time axis given by τ and the reflection slope given by \(\frac{\partial \tau}{\partial x},\) instead of t and p x , respectively, we need to eliminate p x from Eqs. (12) and (13). This task can be achieved with the help of the following explicit relation, derived in Appendix 1,

where τ x = \(\frac{\partial \tau}{\partial x}\), and

Inserting Eq. (14) into Eqs. (12) and (13) yields exact, yet complicated equations, describing the continuation process for v and η. In summary, these equations have the form

and

Equations of the form (15) and (16) contain all the necessary information about the kinematic laws of anisotropy continuation in the domain of zero-offset migration.

Linearization

A useful approximation of Eqs. (15) and (16) can be obtained by simply setting η equal to zero in the right hand side of the equations. Under this approximation, Eq. (15) leads to the kinematic velocity-continuation equation for elliptically anisotropic media, which has the following relatively simple form:

It is interesting to note that setting v = v v , yields Fomel’s expression for isotropic media (Fomel 1996) given by

Alkhalifah (1998) have shown that time–domain processing algorithms for elliptically anisotropic media should be the same as those for isotropic media. However, in anisotropic continuation, elliptical anisotropy and isotropy differ by a vertical scaling factor that is related to the difference between the vertical and NMO velocities. In isotropic media, when velocity is continued, both the vertical and NMO velocities (which are the same) are continued together, whereas in anisotropic media (including elliptically anisotropic) the NMO-velocity continuation is separated from the vertical velocity one, and Eq. (17) corresponds to continuation only in the NMO velocity. This also implies that Eq. (17) is more flexible than Eq. (18), in that we can isolate the vertical velocity continuation (a parameter that is usually ambiguous in surface processing) from the rest of the continuation process. Using \(\tau=\frac{z}{v_v},\) where z is depth, we immediately obtain the equation

which represents the vertical velocity continuation.

Setting η = 0 and v = v v in Eq. (16) leads to the following kinematic equation for η-continuation:

We include more discussion about different aspects of linearization in Appendix 2. The next section presents the analytic solution of Eq. (17). Later in this paper, we compare the analytic solution with a numerical synthetic example.

Ordinary differential equation representation: anisotropic rays

According to the classic rules of mathematical physics, the solution of the kinematic equations (15) and (16) can be obtained by solving the following system of ordinary differential equations:

Here m stands for either v or η, τ x = \(\frac{\partial\tau}{\partial x}\), \(f_m =\frac{\partial \tau}{\partial m}\). To trace the v and η rays, we must first identify the initial values x0,τ0,τx0, and τm0 from the boundary conditions. The variables x0 andτ0 describe the initial position of a reflector in a time-migrated section, τx0 describes its migrated slope, andτm0 is simply obtained from Eqs. (15) or (16).

Using the exact kinematic expressions for f, the results in rather complicated representations of the ordinary differential equations. The linearized expressions, on the other hand, are simple and allow for a straightforward analytical formulation of the ray tracing system.

From kinematics to dynamics

The kinematic η-continuation equation (17) corresponds to the following linear fourth-order dynamic equation

where the t coordinate refers to the vertical traveltime τ, and P (t, x, η) is the migrated image, parameterized in the anisotropy parameter η. To find the correspondence between Eqs. (17) and (21), it is sufficient to apply a ray-theoretical model of the image

as a trial solution to (21). Here the surface t = τ (x, η) is the anisotropy continuation “wavefront”—the image of a reflector for the corresponding value of η, and the function A is the amplitude. Substituting the trial solution into the partial differential equation (21) and considering only the terms with the highest asymptotic order (those containing the fourth-order derivative of the wavelet f), we arrive at the kinematic equation (17). The next asymptotic order (the third-order derivatives of f) gives us the linear partial differential equation of the amplitude transport, as follows:

We can see that when the reflector is flat (τ x = 0 and τ xx = 0), equation (23) reduces to the equality

and the amplitude remains unchanged for different η. This is of course a reasonable behavior in the case of a flat reflector. It does not guarantee although that the amplitudes, defined by Eq. (23), behave equally well for dipping and curved reflectors. The amplitude behavior may be altered by adding low order terms to Eq. (21). According to the ray theory, such terms can influence the amplitude behavior, but do not change the kinematics of the wave propagation.

An appropriate initial value condition for Eq. (21) is the result of isotropic migration that corresponds to the η = 0 section in the (t, x, η) domain. In practice, the initial value problem can be solved by a finite-difference technique.

Synthetic test

Residual post-stack migration operators can be obtained by generating synthetic data for a model consisting of diffractors for given medium parameters and then migrating the same data with different medium parameters. For example, we can generate diffractions for isotropic media and migrate those diffractions using an anisotropic migration. The resultant operator describes the correction needed to transform an isotropically migrated section to an anisotropic one, that is the anisotropic residual migration operator.

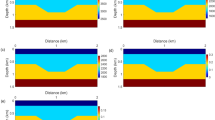

Figure 1 shows such synthetic operators overlaid by kinematically calculated operators that were computed with the help of Eq. (17) (the continuation equations for the case of smallη). Despite the inherent accuracy of the synthetic operators, they suffer from the lack of aperture in modeling the diffractions, and therefore, beyond a certain angle the operators vanish and start to deviate. The agreement between the synthetic and calculated operators for small angles, especially for the η = 0.1 case, promises reasonable results in future dynamic implementations.

Residual post-stack migration operators calculated by solving Eq. (17), overlaid above synthetic operators. The synthetic operators are obtained by applying TI post-stack migration with η = 0.1 (left) and η = 0.2 (right) to three diffractions generated considering isotropic media. The NMO velocity for the modeling and migration is 2.0 km/s

Conclusions

We have extended the concept of velocity continuation in isotropic media to continuations in both the NMO velocity and the anisotropy parameter η for VTI media. Despite the fact that we have considered the simple case of post-stack migration separately, the exact kinematic equations describing the continuation process are anything, but simple. However, useful insights into this problem are deduced from linearized approximations of the continuation equations. These insights include the following observations:

-

The leading order behavior of the velocity continuation is proportional to τ 2 x , which corresponds to small or moderate dips.

-

The leading order behavior of the η continuation is proportional to τ 4 x , which corresponds to moderate or steep dips.

-

Both leading terms are independent of the strength of anisotropy (η).

In practical applications, the initial migrated section is obtained by isotropic migration, and, therefore, the residual process is used to correct for anisotropy. Setting η = 0 in the continuation equations for this type of an application is a reasonable approximation, given that η = 0 is the starting point and we consider only weak to moderate degrees of anisotropy (η ≈ 0.1). Numerical experiments with synthetically generated operators confirm this conclusion.

References

Alkhalifah T (1998) Acoustic approximations for processing in transversely isotropic media. Geophysics 63:623–631

Alkhalifah T (2005) Residual dip moveout in VTI media. Geophys Prosp 53:1–12

Alkhalifah T, Tsvankin I (1995) Velocity analysis for transversely isotropic media. Geophysics 60:1550–1566

Etgen J (1990) Residual prestack migration and interval velocity estimation. PhD thesis, Stanford University

Fomel S (1996) Migration and velocity analysis by velocity continuation

Press WH, Teukolsky SA, Vetterling WT, Flannery BP (1992) Numerical recipes, the art of scientific computing. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Rothman DH, Levin SA, Rocca F (1985) Residual migration—applications and limitations. Geophysics 50:110–126

Thomsen L (1986) Weak elastic anisotropy. Geophysics 51:1954–1966 (discussion in GEO-53-04-0558-0560 with reply by author)

Acknowledgments

Tariq Alkhalifah would like to thank KAUST and KACST for their financial support, and Sergey Fomel likes to thank the University of Texas, Austin for its support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Relating the zero-offset and migration slopes

The chain rule of differentiation leads to the equality

where \(p_{\tau}= -\frac{\partial t}{\partial \tau}.\) It is convenient to transform equality (24) to the form

Using the expression for p τ from the main text, we can write Eq. (25) as a quadratic polynomial in p 2 x as follows

where

and

Because η can be small (as small as zero for isotropic media), we use the following form of solution to the quadratic equation

(Press et al. 1992). This form does not go to infinity asη approaches 0. We choose the solution with the negative sign in front of the square root, because this solution complies with the isotropic result whenη is equal to zero.

Appendix 2

Linearized approximations

Although the exact expressions might be sufficiently constructive for actual residual migration applications, linearized forms are still useful, because they give us valuable insights into the problem. The degree of parameter dependency for different reflector dips is one of the most obvious insights in the anisotropy continuation problem. Perturbation of a small parameter provides a general mechanism to simplify functions by recasting them into power series expansion over a parameter that has small values. Two variables can satisfy the small perturbation criterion in this problem: The anisotropy parameterη (η ≪ 1) and the reflection dip τ x (τ x v≪ 1 or p x v ≪ 1).

Setting η = 0 yields Eq. (17) for the velocity continuation in elliptical anisotropic media and

which represents the case when we initially introduce anisotropy into our model.

Because p x (the zero-offset slope) is typically lower than τ x (the migrated slope), we perform initial expansions in terms of y = p x v. Applying the Taylor series expansion of Eqs. (12) and (13) in terms of y and dropping all terms beyond the fourth power in y, we obtain

and

Although both equations are equal to zero for p x =0, the leading term in the velocity continuation is proportional to p 2 x , whereas the the leading term in the η continuation is proportional to p 4 x . As a result the velocity continuation has greater influence at lower angles than the η continuation. It is also interesting to note that both leading terms are independent of the size of anisotropy (η).

Despite the typically lower values of p x , expansions in terms of τ x are more important, but less accurate. For small τ x , p x ≈ τ x , and, therefore, the leading-term behavior of τ x expansions is the same as that of p x . As a result, we arrive at the equation

and

Most of the terms in Eqs. (30) and (31) are functions of the difference between the vertical and NMO velocities. Therefore, for simplicity and without a loss of generality, we set v v = v and keep only the terms up to the eighth power in τ x . The resultant expressions take the form

and

Curiously enough, the second term of the η continuation heavily depends on the size of anisotropy (∼20η). The first term of Eq. (32) (∼ τ 2 x ) is the isotropic term; all other terms in Eqs. (32) and (33) are induced by the anisotropy.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Alkhalifah, T., Fomel, S. The basic components of residual migration in VTI media using anisotropy continuation. J Petrol Explor Prod Technol 1, 17–22 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-011-0006-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-011-0006-6