Abstract

The use of biologic grafts in the surgical treatment of pelvic prolapse repair has been an intriguing prospect for several years. These tissues have been thought to potentially combine favorable attributes of both autologous and synthetic tissues. These tissues are harvested and undergo complex decellularization, dehydration, terminal sterilization, and possibly cross-linking. It is these steps that determine the graft’s eventual biocompatibility and potential for remodeling. A PubMed literature search has revealed a number of studies evaluating cadaveric allografts and bovine and porcine xenografts in repairs of the anterior, posterior, and apical compartments. While the study quality varies significantly, overall, there is little compelling evidence to unequivocally support the use of a biologic tissue in any compartment. Furthermore, an analysis of postoperative complications reveals a similarity in graft-related complication profiles between some biologic grafts and synthetic meshes.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: •Of importance ••Of major importance

Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, et al. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501–6.

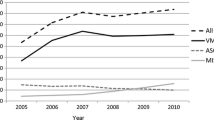

Wu JM, Hundley AF, Fulton RG, Myers ER. Forecasting the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in U.S. women: 2010 to 2050. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1278–83.

Luber KM, Boero S, Choe JY. The demographics of pelvic floor disorders: current observations and future projections. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1496–501.

Subak LL, Waetjen LE, van den Eeden S, et al. Cost of pelvic organ prolapse surgery in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:646–51.

Jelovsek JE, Barber MD. Women seeking treatment for advanced pelvic organ prolapse have decreased body image and quality of life. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1455–61.

Wein AJ. Voiding function and dysfunction, bladder physiology and pharmacology, and female urology. J Urol. 2011;186:2328–30.

Davila GW, Drutz H, Deprest J. Clinical implications of the biology of grafts: conclusions of the 2005 IUGA Grafts Roundtable. Int Urogynecol J. 2006;17:S51–5.

Jia X, Glazener C, Mowatt G, et al. Efficacy and safety of using mesh or grafts in surgery for anterior and/or posterior vaginal wall prolapse: systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2008;115:1350–61.

Sung VW, Rogers RG, Schaffer JI, et al. Graft use in transvaginal pelvic organ prolapse repair: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:1131–42.

• Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Glazener C: Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010, 4: CD004014. This is a recent Cochrane review regarding POP repair.

Cumberland VH. A preliminary report on the use of prefabricated nylon weave in the repair of ventral hernia. Med J Aust. 1952;1:143–4.

Scales JT. Tissue reactions to synthetic materials. Proc R Soc Med. 1953;46:647–52.

Cosson M, Debodinance P, Boukerrou M, et al. Mechanical properties of synthetic implants used in the repair of prolapse and urinary incontinence in women: which is the ideal material? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2003;14:169–78.

Kushner L, Mathrubutham M, Burney T, et al. Excretion of collagen-derived peptides is increased in women with stress urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodynam. 2004;23:198–203.

Mangera A, Bullock AJ, Chapple CR, MacNeil S. Are biomechanical properties predictive of the success of prostheses used in stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse? A systematic review. Neurourol Urodynam. 2012;31:13–21.

Gilbert TW, Freund JM, Badylak SF. Quantification of DNA in biologic scaffold materials. J Surg Res. 2009;152:135–9.

Trabuco EC, Klingele CJ, Gebhart JB. Xenograft use in reconstructive pelvic surgery: a review of the literature. Int Urogynecol J. 2007;18:555–63.

Deprest J, Zheng F, Konstantinovic M, et al. The biology behind fascial defects and the use of implants in pelvic organ prolapse repair. Int Urogynecol J. 2005;17:S16–25.

Liles W, Van Voorhis WC. Nomenclature and biological significance of cytokines involved in inflammation and host immune response. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1573–82.

Tang L, Eaton JW. Fibrinogen mediates acute inflammatory responses to biomaterials. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2147–56.

Tang L, Eaton JW. Inflammatory responses to biomaterials. Am J Clin Pathol. 1995;103:466–71.

Horowitz SM, Gonzales JB. Effects of polyethylene on macrophages. J Orthop Res. 1997;15:50–6.

Hodde J, Badylak S, Brightman A, Voytik-Harbin S. Glycosaminoglycan content of small intestinal submucosa: a bioscaffold for tissue replacement. Tissue Engineering. 1996;2:209–17.

McPherson JM, Sawamura SJ, Condell RA, et al. The effects of heparin on the physicochemical properties of reconstituted collagen. Coll Relat Res. 1988;8:65–82.

Murphy GF, Orgill DP, Yannas IV. Partial dermal regeneration is induced by biodegradable collagen-glycosaminoglycan grafts. Lab Invest. 1990;62:305–13.

Amundsen CL, Visco AG, Ruiz H, et al. Outcome in 104 pubovaginal slings using freeze-dried allograft fascia lata from a single tissue bank. Urology. 2000;56(Suppl 6A):2–8.

Amrute KV, Badlani GH. The science behind biomaterials in female stress urinary incontinence surgery. ScientificWorldJournal. 2009;9:23–31.

•• Crapo PM, Gilbert TW, Badylak SF: An overview of tissue and whole organ decellularization processes. Biomaterials 2011, 32: 3233-3243. This is a state-of-the-art review of details regarding processing and treatment of biologic tissue during decellularization.

Moalli PA. Cadaveric fascia lata. Int Urogyn J. 2006;17:S48–50.

Lemer ML, Chaikin DC, Blaivas JG. Tissue strength analysis of autologous and cadaveric allografts for the pubovaginal sling. Neurourol Urodynam. 1999;18:497–503.

Fitzgerald MP, Mollenhauer J, Bitterman P, et al. Functional failure of fascia lata allografts. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:1339–46.

Badylak S, Liang A, Record R, et al. Endothelial cell adherence to small intestinal submucosa: an acellular bioscaffold. Biomaterials. 1999;20:2257–63.

Santucci RA, Barber TD. Resorbable extracellular matrix grafts in urologic reconstruction. Int Braz J Urol. 2005;31:192–203.

Connolly RJ. Evaluation of a unique bovine collagen matrix for soft tissue repair and reinforcement. Int Urogynecol J. 2006;17:S44–7.

Sackett DL, Strauss SE, Richardson WS, et al. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. Philadelphia: Churchill-Livingstone; 2000.

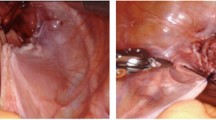

Gomelsky A, Haverkorn RM, Simoneaux WJ, et al. Incidence and management of vaginal extrusion of acellular porcine dermis after incontinence and prolapse surgery. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:1337–41.

Allman AJ, McPherson TB, Badylak SF, et al. Xenogeneic extracellular matrix grafts elicit a TH2-restricted immune response. Transplantation. 2001;71:1631–40.

Ho KL, Witte MN, Bird ET. 8-ply small intestinal submucosa tension-free sling: spectrum of postoperative inflammation. J Urol. 2004;171:268–71.

Kalota SJ. Small intestinal submucosa tension-free sling: postoperative inflammatory reactions and additional data. J Urol. 2004;172:1349–50.

• http://www.cookmedical.com/content/mmedia/COOK_Comments_for%20FDAOb-GynPanel_re_Pelvic%20OrganProlapse.pdf (accessed March 30, 2012). This is a succinct and updated review of graft-related complications and postoperative sequelae such as pain and dyspareunia after biologic, synthetic, and standard anterior compartment repairs.

Groutz A, Chaikin DC, Theusen E, Blaivas JG. Use of cadaveric solvent-dehydrated fascia lata for cystocele repair – preliminary results. Urology. 2001;58:179–83.

Powell CR, Simsiman AJ, Menefee SA. Anterior vaginal wall hammock with fascia lata for the correction of stage 2 or greater anterior vaginal compartment relaxation. J Urol. 2004;171:264–7.

Frederick RW, Leach GE. Cadaveric prolapse repair with sling: intermediate outcomes with 6 months to 5 years of followup. J Urol. 2005;173:1229–33.

Gandhi S, Goldberg RP, Kwon C, et al. A prospective randomized trial using solvent dehydrated fascia lata prevention of recurrent anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1649–54.

Chung SY, Franks M, Smith CP, et al. Technique of combined pubovaginal sling and cystocele repair using a single piece of cadaveric dermal graft. Urology. 2002;59:538–41.

Ward RM, Sung VW, Clemons JL, Myers DL. Vaginal paravaginal repair with AlloDerm graft: long-term outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:670.e1–5.

Botros SM, Sand PK, Beaumont JL, et al. Arcus-anchored acellular dermal graft compared to anterior colporrhaphy for stage II cystoceles and beyond. Int Urogynecol J. 2009;20:1265–71.

Gomelsky A, Rudy DC, Dmochowski RR. Porcine dermis interposition graft for repair of high grade anterior compartment defects with or without concomitant pelvic organ prolapse procedures. J Urol. 2004;171:1581–4.

Mahdy A, Elmissiry M, Ghoniem G. The outcome of transobturator cystocele repair using biocompatible porcine dermis graft: our experience with 32 cases. Int Urogynecol J. 2008;19:1647–52.

Ramanah R, Mairot J, Clement MC, et al. Evaluating the porcine dermis graft Intexen® in three compartment transvaginal pelvic prolapse repair. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21:1151–6.

Salomon LJ, Detchev R, Barranger E, et al. Treatment of anterior vaginal wall prolapse with porcine skin collagen implant by the transobturator route: preliminary results. Eur Urol. 2004;45:219–25.

David-Montefiore E, Barranger E, Dubernard G, et al. Treatment of genital prolapse by hammock using porcine skin collagen implant (Pelvicol). Urology. 2005;66:1314–8.

Simsiman AJ, Luber KM, Menefee SA. Vaginal paravaginal repair with porcine dermal reinforcement: correction of advanced anterior vaginal prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1832–6.

Wheeler II TL, Richter HE, Duke AG, et al. Outcomes with porcine graft placement in the anterior vaginal compartments in patients who undergo high vaginal uterosacral suspension and cystocele repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1486–91.

Ross J. Porcine dermal hammock for repair of anterior and posterior vaginal wall prolapse: 5-year outcome. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:459–65.

Darai E, Coutant C, Rouzier R, et al. Genital prolapse repair using porcine skin implant and bilateral sacrospinous fixation: midterm functional outcome and quality-of-life assessment. Urology. 2009;73:245–50.

Koutsougeras G, Nicolaou P, Karamanidis D, et al. Effectiveness of transvaginal colporrhaphy with porcine acellular collagen matrix in the treatment of moderate to severe cystoceles. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2009;36:179–81.

de Boer TA, Gietelink DA, Hendriks JC, Vierhout ME. Factors influencing success of pelvic organ prolapse repair using porcine dermal implant Pelvicol®. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;149:112–6.

Meschia M, Pifarotti P, Bernasconi F, et al. Porcine skin collagen implants to prevent anterior vaginal wall prolapse recurrence: a multicenter, randomized study. J Urol. 2007;177:192–5.

Hviid U, Hviid TV, Rudnicki M. Porcine skin collagen implants for anterior vaginal wall prolapse: a randomised prospective controlled study. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21:529–34.

Dahlgren E, Kjolhede P. Long-term outcome of porcine skin graft in surgical treatment of recurrent pelvic organ prolapse. An open randomized controlled multicenter study Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90:1393–401.

Leboeuf L, Miles RA, Kim SS, Gousse AE. Grade 4 cystocele repair using four-defect repair and porcine xenograft acellular matrix (Pelvicol): outcome measures using SEAPI. Urology. 2004;64:282–6.

Natale F, La Penna C, Padoa A, et al. A prospective, randomized, controlled study comparing Gynemesh®, a synthetic mesh, and Pelvicol®, a biologic graft, in the surgical treatment of recurrent cystocele. Int Urogynecol J. 2009;20:75–81.

•• Menefee SA, Duer KY, Lukacz ES, et al.: Colporrhaphy compared with mesh or graft-reinforced vaginal paravaginal repair for anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Obstet Gynecol 2011, 118: 1337-1344. This was an RCT reporting 24-month follow-up in women undergoing cross-linked PD, polypropylene graft, or standard anterior colporrhaphy. Significant subjective and objective improvement was seen for polypropylene versus PD and standard repair.

Handel LN, Frenkl TL, Kim YH. Results of cystocele repair: a comparison of traditional anterior colporrhaphy, polypropylene mesh and porcine dermis. J Urol. 2007;178:153–6.

Armitage S, Seman EI, Keirse MJ: Use of Surgisys for treatment of anterior and posterior vaginal wall prolapse. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012;2012:376251. Epub 2012 Jan 15.

Jeffery ST, Doumouchtsis SK, Parappallil S, et al. Outcomes, recurrence rates, and postoperative sexual function after secondary vaginal prolapse surgery using the small intestinal submucosa graft. J Pelvic Med Surg. 2009;15:151–6.

Chaliha C, Khalid U, Campagna L, et al. SIS graft for anterior vaginal wall prolapse repair—a case-controlled study. Int Urogynecol J. 2006;17:492–7.

Feldner Jr PC, Castro RA, Cipolotti LA, et al. Anterior vaginal wall prolapse: a randomized controlled trial of SIS graft versus traditional colporrhaphy. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21:1057–63.

Mouritsen L, Kronschnabl M, Lose G. Long-term results of vaginal repairs with and without xenograft reinforcement. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21:467–73.

Reid RI, You H, Luo K. Site-specific prolapse surgery. I. Reliability and durability of native tissue paravaginal repair. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:591–9.

Goldstein HB, Maccarone J, Naughton MJ, et al. A multicenter prospective trial evaluating fetal bovine dermal graft (Xenform® Matrix) for pelvic reconstructive surgery. BMC Urology. 2010;10:21.

Guerette NL, Peterson TV, Aguirre OA, et al. Anterior repair with or without collagen matrix reinforcement. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:56–65.

Dell JR, O’Kelley KR. PelviSoft BioMesh augmentation of rectocele repair: the initial clinical experience in 35 patients. Int Urogynecol J. 2005;16:44–7.

Taylor GB, Moore RD, Miklos JR, Mattox TF. Posterior repair with perforated porcine dermal graft. Int Braz J Urol. 2008;34:84–90.

Novi JM, Bradley CS, Mahmoud NN, et al. Sexual function in women after rectocele repair with acellular porcine dermis graft vs site-specific rectovaginal fascia repair. Int Urogynecol J. 2007;18:1163–9.

Drake NL, Weidner AC, Webster GD, Amundsen CL. Patient characteristics and management of dermal allograft extrusions. Int Urogynecol J. 2005;16:375–7.

Kobashi KC, Leach GE, Frederick R, et al. Initial experience with rectocele repair using nonfrozen cadaveric fascia lata interposition. Urology. 2005;66:1203–7.

Kohli N, Miklos JR. Dermal graft-augmented rectocele repair. Int Urogynecol J. 2003;14:146–9.

Altman D, Zetterstrom J, Lopez A, et al. Functional and anatomic outcome after transvaginal rectocele repair using collagen mesh: a prospective study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1233–42.

Smart NJ, Mercer-Jones MA. Functional outcome after transperineal rectocele repair with porcine dermal collagen implant. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1–6.

Biehl RC, Moore RD, Miklos JR, et al. Site-specific rectocele repair with dermal graft augmentation: comparison of porcine dermal xenograft (Pelvicol®) and human dermal allograft. Surg Tech Int. 2008;17:174–80.

Paraiso MF, Barber MD, Muir TW, Walters MD. Rectocele repair: a randomized trial of three surgical techniques including graft augmentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1762–71.

Flynn MK, Webster GD, Amundsen CL. Abdominal sacral colpopexy with allograft fascia lata: one-year outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1496–500.

FitzGerald MP, Edwards SR, Fenner D. Medium-term follow-up on use of freeze-dried, irradiated donor fascia for sacrocolpopexy and sling procedures. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2004;15:238–42.

Gregory WT, Otto LN, Bergstrom JO, Clark AL. Surgical outcome of abdominal sacrocolpopexy with synthetic mesh versus abdominal sacrocolpopexy with cadaveric fascia lata. Int Urogynecol J. 2005;16:369–74.

Loffeld C, Thijs S, Mol BW, et al. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy: a comparison of Prolene® and Tutoplast® mesh. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88:826–30.

Culligan PJ, Blackwell L, Goldsmith LJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing fascia lata and synthetic mesh for sacral colpopexy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:29–37.

Claerhout F, De Ridder D, Van Beckevoort D, et al. Sacrocolopexy using xenogenic acellular collagen in patients at increased risk for graft-related complications. Neurourol Urodynam. 2010;29:563–7.

Deprest J, De Ridder D, Roovers J-P, et al. Medium term outcome of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy with xenografts compared to synthetic grafts. J Urol. 2009;182:2362–8.

Altman D, Anzen B, Brismar S, et al. Long-term outcome of abdominal sacrocolpopexy using xenograft compared with synthetic mesh. Urology. 2006;67:719–24.

Ross JW. The use of a xenogenic barrier to prevent mesh erosion with laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:470–4.

Quiroz LH, Gutman RE, Shippey S, et al.: Abdominal sacrocolpopexy: anatomic outcomes and complications with Pelvicol, autologous and synthetic graft materials. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008, 198: 557.e1-557.e5.

• Deffieux X, Savary D, Letouzey V, et al.: [Prevention of the complications related to the use of prosthetic meshes in prolapse surgery: guidelines for clinical practice - literature review]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 2011, 40: 827-850. This is an updated systematic review of abdominal sacrocolpopexy.

Disclosure

Dr. Gomelsky has served as a consultant for the Coloplast Group.

Dr. Dmochowski has served as a consultant for Allergan, Merck & Co., and Johnson & Johnson.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gomelsky, A., Dmochowski, R.R. Biologic Materials for Pelvic Floor Reconstruction. Curr Bladder Dysfunct Rep 7, 201–209 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11884-012-0139-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11884-012-0139-6