Abstract

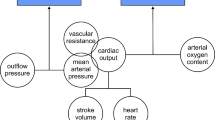

Assessment of the hemodynamics and volume status is an important daily task for physicians caring for critically ill patients. There is growing consensus in the critical care community that the “traditional” methods—e.g., central venous pressure or pulmonary artery occlusion pressure—used to assess volume status and fluid responsiveness are not well supported by evidence and can be misleading. Our purpose is to provide here an overview of the knowledge needed by ICU physicians to take advantage of mechanical cardiopulmonary interactions to assess volume responsiveness. Although not perfect, such dynamic assessment of fluid responsiveness can be helpful particularly in the passively ventilated patients. We discuss the impact of phasic changes in lung volume and intrathoracic pressure on the pulmonary and systemic circulation and on the heart function. We review how respirophasic changes on the venous side (great veins geometry) and arterial side (e.g., stroke volume/systolic blood pressure and surrogate signals) can be used to detect fluid responsiveness or hemodynamic alterations commonly encountered in the ICU. We review the physiological limitations of this approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Feihl F, Broccard AF. Interactions between respiration and systemic hemodynamics. Part II: practical implications in critical care. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(2):198–205. doi:10.1007/s00134-008-1298-y.

Feihl F, Broccard AF. Interactions between respiration and systemic hemodynamics Part I: basic concepts. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(1):45–54. doi:10.1007/s00134-008-1297-z.

Guyton AC, Jones CE, Coleman TG. Circulatory physiology: cardiac output and its regulation. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1973.

Magder S. Venous return and cardiac output. In: Perret C, Feihl F, editors. Les interactions cardio-pulmonaires. Paris: Arnette; 1994. p. 29–36.

Magder S. The classical Guyton view that mean systemic pressure, right atrial pressure, and venous resistance govern venous return is/is not correct. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101(5):1533. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00903.2006.

Marik PE, Baram M, Vahid B. Does central venous pressure predict fluid responsiveness? A systematic review of the literature and the tale of seven mares. Chest. 2008;134(1):172–8. doi:10.1378/chest.07-2331.

Kumar A, Anel R, Bunnell E, Habet K, Zanotti S, Marshall S, et al. Pulmonary artery occlusion pressure and central venous pressure fail to predict ventricular filling volume, cardiac performance, or the response to volume infusion in normal subjects. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(3):691–9.

Marini JJ, Culver BH, Butler J. Effect of positive end-expiratory pressure on canine ventricular function curves. J Appl Physiol. 1981;51(6):1367–74.

Wise RA, Robotham JL, Bromberger-Barnea B, Permutt S. Effect of PEEP on left ventricular function in right-heart-bypassed dogs. J Appl Physiol. 1981;51(3):541–6.

Marini JJ, Culver BH, Butler J. Mechanical effect of lung distention with positive pressure on cardiac function. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1981;124(4):382–6.

Butler J, Schrijen F, Henriquez A, Polu JM, Albert RK. Cause of the raised wedge pressure on exercise in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;138(2):350–4.

Jardin F, Farcot JC, Boisante L, Prost JF, Gueret P, Bourdarias JP. Mechanism of paradoxic pulse in bronchial asthma. Circulation. 1982;66:887–94.

Blaustein AS, Risser TA, Weiss JW, Parker JA, Holman BL, McFadden ER. Mechanisms of pulsus paradoxus during resistive respiratory loading and asthma. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8(3):529–36.

Howell J, Permutt D, Proctor Riley R. Effect of inflation of the lung on different parts of the pulmonary vascular bed. J Appl Physiol. 1961;16:71–6.

van den Berg PC, Jansen JR, Pinsky MR. Effect of positive pressure on venous return in volume-loaded cardiac surgical patients. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92(3):1223–31. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00487.2001.

Nanas S, Magder S. Adaptations of the peripheral circulation to PEEP. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146(3):688–93.

Jellinek H, Krenn H, Oczenski W, Veit F, Schwarz S, Fitzgerald RD. Influence of positive airway pressure on the pressure gradient for venous return in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2000;926–32.

Fessler HE, Brower RG, Wise RA, Permutt S. Effects of positive end-expiratory pressure on the canine venous return curve. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146(1):4–10.

Fessler HE, Brower RG, Shapiro EP, Permutt S. Effects of positive end-expiratory pressure and body position on pressure in the thoracic great veins. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148(6 Pt 1):1657–64.

Brienza N, Revelly JP, Ayuse T, Robotham JL. Effects of PEEP on liver arterial and venous blood flows. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(2):504–10.

Kimura BJ, Dalugdugan R, Gilcrease GWr, Phan JN, Showalter BK, Wolfson T. The effect of breathing manner on inferior vena caval diameter. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2011;12(2):120–3. doi:10.1093/ejechocard/jeq157.

Willeput R, Rondeux C, De Troyer A. Breathing affects venous return from legs in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1984;57(4):971–6.

Permutt S, Howell J, Proctor Riley R. Effect of lung inflation on on static pressure-volume characteristics of pulmonary vessels. J Appl Physiol. 1961;16:64–70.

Brower R, Wise RA, Hassapoyannes C, Bromberger-Barnea B, Permutt S. Effect of lung inflation on lung blood volume and pulmonary venous flow. J Appl Physiol. 1985;58(8750–7587):954–63.

Scharf SM. Cardiopulmonary interactions. In: Scharf SM, editor. Cardiopulmonary physiology in critical care. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1992. p. 333–55.

Santamore WP, Heckman JL, Bove AA. Cardiovascular changes from expiration to inspiration during IPPV. Am J Physiol. 1983;245(2):H307–12.

Mitchell JR, Whitelaw WA, Sas R, Smith ER, Tyberg JV, Belenkie I. RV filling modulates LV function by direct ventricular interaction during mechanical ventilation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289(2):H549–57. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.01180.2004.

Buda AJ, Pinsky MR, Ingels NB Jr, Daughters GT, Stinson EB, Alderman EL. Effect of intrathoracic pressure on left ventricular performance. N Engl J Med. 1979;301(9):453–9.

Pinsky MR, Summer WR, Wise RA, Permutt S, Bromberger-Barnea B. Augmentation of cardiac function by elevation of intrathoracic pressure. J Appl Physiol. 1983;54(4):950–5.

Peters J, Kindred MK, Robotham JL. Transient analysis of cardiopulmonary interactions II. Systolic events. J Appl Physiol. 1988;64(4):1518–26.

Hakim TS, Michel RP, Chang HK. Effect of lung inflation on pulmonary vascular resistance by arterial and venous occlusion. J Appl Physiol. 1982;53(5):1110–5.

Olsen CO, Tyson GS, Maier GW, Spratt JA, Davis JW, Rankin JS. Dynamic ventricular interaction in the conscious dog. Circ Res. 1983;52(1):85–104.

Magder S, Georgiadis G, Cheong T. Respiratory variations in right atrial pressure predic the response to fluid challenge. J Crit Care. 1992;7:76–85.

Diebel L, Wilson RF, Heins J, Larky H, Warsow K, Wilson S. End-diastolic volume versus pulmonary artery wedge pressure in evaluating cardiac preload in trauma patients. J Trauma. 1994;37(6):950–5.

Tavernier B, Makhotine O, Lebuffe G, Dupont J, Scherpereel P. Systolic pressure variation as a guide to fluid therapy in patients with sepsis-induced hypotension. Anesthesiology. 1998;89(6):1313–21.

Michard F, Boussat S, Chemla D, Anguel N, Mercat A, Lecarpentier Y, et al. Relation between respiratory changes in arterial pulse pressure and fluid responsiveness in septic patients with acute circulatory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(1):134–8.

Preau S, Dewavrin F, Soland V, Bortolotti P, Colling D, Chagnon JL, et al. Hemodynamic changes during a deep inspiration maneuver predict fluid responsiveness in spontaneously breathing patients. Cardiol Res Pract. 2012;38(3):825–8.

Monge Garcia MI, Gil Cano A, Diaz Monrove JC. Arterial pressure changes during the valsalva maneuver to predict fluid responsiveness in spontaneously breathing patients. Intensive Care Med 2009;35(1):77–84. doi:10.1007/s00134-008-1295-1.

Cavallaro F, Sandroni C, Marano C, La Torre G, Mannocci A, De Waure C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of passive leg raising for prediction of fluid responsiveness in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(9):1475–83. doi:10.1007/s00134-010-1929-y.

Coriat P, Vrillon M, Perel A, Baron JF, Le Bret F, Saada M, et al. A comparison of systolic blood pressure variations and echocardiographic estimates of end-diastolic left ventricular size in patients after aortic surgery. Anesth Analg. 1994;78(1):46–53.

Zhang Z, Lu B, Sheng X, Jin N. Accuracy of stroke volume variation in predicting fluid responsiveness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Anesth. 2011;25(6):904–16. doi:10.1007/s00540-011-1217-1.

Cannesson M, Le Manach Y, Hofer CK, Goarin JP, Lehot JJ, Vallet B, et al. Assessing the diagnostic accuracy of pulse pressure variations for the prediction of fluid responsiveness: a “gray zone” approach. Anesthesiology. 2011;115(2):231–41. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e318225b80a.

Lakhal K, Ehrmann S, Benzekri-Lefevre D, Runge I, Legras A, Dequin PF, et al. Respiratory pulse pressure variation fails to predict fluid responsiveness in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care. 2011;15(2):R85. doi:10.1186/cc10083.

Monnet X, Bleibtreu A, Ferre A, Dres M, Gharbi R, Richard C, et al. Passive leg-raising and end-expiratory occlusion tests perform better than pulse pressure variation in patients with low respiratory system compliance. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(1):152–7. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31822f08d7.

De Backer D, Pinsky MR. Can one predict fluid responsiveness in spontaneously breathing patients? Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(7):1111–3. doi:10.1007/s00134-007-0645-8.

Soubrier S, Saulnier F, Hubert H, Delour P, Lenci H, Onimus T, et al. Can dynamic indicators help the prediction of fluid responsiveness in spontaneously breathing critically ill patients? Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(7):1117–24. doi:10.1007/s00134-007-0644-9.

Szold A, Pizov R, Segal E, Perel A. The effect of tidal volume and intravascular volume state on systolic pressure variation in ventilated dogs. Intensive Care Med. 1989;15(6):368–71.

Reuter DA, Bayerlein J, Goepfert MS, Weis FC, Kilger E, Lamm P, et al. Influence of tidal volume on left ventricular stroke volume variation measured by pulse contour analysis in mechanically ventilated patients. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(3):476–80. doi:10.1007/s00134-003-1649-7.

Renner J, Cavus E, Meybohm P, Tonner P, Steinfath M, Scholz J, et al. Stroke volume variation during hemorrhage and after fluid loading: impact of different tidal volumes. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2007;51(5):538–44. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.2007.01282.x.

Duperret S, Lhuillier F, Piriou V, Vivier E, Metton O, Branche P, et al. Increased intra-abdominal pressure affects respiratory variations in arterial pressure in normovolaemic and hypovolaemic mechanically ventilated healthy pigs. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(1):163–71. doi:10.1007/s00134-006-0412-2.

Preisman S, Kogan S, Berkenstadt H, Perel A. Predicting fluid responsiveness in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: functional haemodynamic parameters including the respiratory systolic variation test and static preload indicators. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95(6):746–55. doi:10.1093/bja/aei262.

Cannesson M, Tran NP, Cho M, Hatib F, Michard F. Predicting fluid responsiveness with stroke volume variation despite multiple extrasystoles. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(1):193–8. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31822ea119.

Willars C, Dada A, Hughes T, Green D. Functional haemodynamic monitoring: the value of SVV as measured by the LiDCORapid in predicting fluid responsiveness in high risk vascular surgical patients. Int J Surg. 2012. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2012.02.003.

Charron C, Caille V, Jardin F, Vieillard-Baron A. Echocardiographic measurement of fluid responsiveness. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2006;12(3):249–54. doi:10.1097/01.ccx.0000224870.24324.cc.

Mandelbaum A, Ritz E. Vena cava diameter measurement for estimation of dry weight in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11(Suppl 2):24–7.

Vieillard-Baron A, Augarde R, Prin S, Page B, Beauchet A, Jardin F. Influence of superior vena caval zone condition on cyclic changes in right ventricular outflow during respiratory support. Anesthesiology. 2001;95(5):1083–8.

Feissel M, Michard F, Faller JP, Teboul JL. The respiratory variation in inferior vena cava diameter as a guide to fluid therapy. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(9):1834–7. doi:10.1007/s00134-004-2233-5.

Barbier C, Loubieres Y, Schmit C, Hayon J, Ricome JL, Jardin F, et al. Respiratory changes in inferior vena cava diameter are helpful in predicting fluid responsiveness in ventilated septic patients. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(9):1740–6. doi:10.1007/s00134-004-2259-8.

Vieillard-Baron A, Chergui K, Rabiller A, Peyrouset O, Page B, Beauchet A, et al. Superior vena caval collapsibility as a gauge of volume status in ventilated septic patients. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(9):1734–9. doi:10.1007/s00134-004-2361-y.

Haciomeroglu P, Ozkaya O, Gunal N, Baysal K. Venous collapsibility index changes in children on dialysis. Nephrology (Carlton). 2007;12(2):135–9. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1797.2006.00700.x.

Juhl-Olsen P, Frederiksen CA, Sloth E. Ultrasound assessment of inferior vena cava collapsibility is not a valid measure of preload changes during triggered positive pressure ventilation: a controlled cross-over study. Ultraschall Med. 2012;33(2):152–9. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1281832.

Lichtenstein D, Karakitsos D. Integrating lung ultrasound in the hemodynamic evaluation of acute circulatory failure (the fluid administration limited by lung sonography protocol). J Crit Care. 2012. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.03.004.

Acknowledgments

The author has no financial relationship to disclose related to the topic of this review.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Broccard, A.F. Cardiopulmonary interactions and volume status assessment. J Clin Monit Comput 26, 383–391 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-012-9387-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-012-9387-4