Abstract

Introduction

Fluid responsiveness prediction is of utmost interest during acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), but the performance of respiratory pulse pressure variation (ΔRESPPP) has scarcely been reported. In patients with ARDS, the pathophysiology of ΔRESPPP may differ from that of healthy lungs because of low tidal volume (Vt), high respiratory rate, decreased lung and sometimes chest wall compliance, which increase alveolar and/or pleural pressure. We aimed to assess ΔRESPPP in a large ARDS population.

Methods

Our study population of nonarrhythmic ARDS patients without inspiratory effort were considered responders if their cardiac output increased by >10% after 500-ml volume expansion.

Results

Among the 65 included patients (26 responders), the area under the receiver-operating curve (AUC) for ΔRESPPP was 0.75 (95% confidence interval (CI95): 0.62 to 0.85), and a best cutoff of 5% yielded positive and negative likelihood ratios of 4.8 (CI95: 3.6 to 6.2) and 0.32 (CI95: 0.1 to 0.8), respectively. Adjusting ΔRESPPP for Vt, airway driving pressure or respiratory variations in pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (ΔPAOP), a surrogate for pleural pressure variations, in 33 Swan-Ganz catheter carriers did not markedly improve its predictive performance. In patients with ΔPAOP above its median value (4 mmHg), AUC for ΔRESPPP was 1 (CI95: 0.73 to 1) as compared with 0.79 (CI95: 0.52 to 0.94) otherwise (P = 0.07). A 300-ml volume expansion induced a ≥2 mmHg increase of central venous pressure, suggesting a change in cardiac preload, in 40 patients, but none of the 28 of 40 nonresponders responded to an additional 200-ml volume expansion.

Conclusions

During protective mechanical ventilation for early ARDS, partly because of insufficient changes in pleural pressure, ΔRESPPP performance was poor. Careful fluid challenges may be a safe alternative.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many appealing indices have been proposed to predict fluid responsiveness, using heart-lung interactions (for example, respiratory variations of pulse pressure (ΔRESPPP)) [1, 2] or passive leg raising [3]. ΔRESPPP requires controlled mechanical ventilation in nonarrhythmic patients sufficiently sedated for not triggering the ventilator [4]. As the use of sedation in the intensive care unit (ICU) has decreased over the past few years, this situation is rarely encountered, except in cases such as severe respiratory failure (such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)) requiring perfect patient-ventilator interactions. Of note, fluid responsiveness prediction is crucial in patients with ARDS because of increased alveolar-capillary membrane permeability [5], and avoiding unnecessary fluid loading has been shown to have a positive effect on patient outcome [6].

Nevertheless, cardiopulmonary interactions are complex in case of ARDS, particularly when lung-protective mechanical ventilation (low tidal volume) is performed as recommended nowadays [5], and several limitations may downplay the usefulness of ΔRESPPP. First, the magnitude of the insufflated tidal volume (Vt) affects the magnitude of ΔRESPPP (or other indices derived from respiratory changes in stroke volume) in non-ARDS or mixed ARDS and non-ARDS patients [7–9]. Thus, the performance of ΔRESPPP becomes poor when the Vt is settled below 8 ml/kg [10, 11]. Second, ARDS patients exhibit a marked decrease in lung and sometimes chest wall compliance [5]. Consequently, airway driving pressure (plateau pressure (Pplat) minus total positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEPt)) for a given Vt is greater in ARDS than in healthy lungs [12]. Therefore, it has been hypothesized that, despite a reduced Vt, cyclic swings in airway pressure are still high enough to maintain ΔRESPPP predictive ability in ARDS patients [13]. However, one may question this assumption. Indeed, ΔRESPPP results of swings in right atrial pressure which are close to pericardial and pleural pressure swings. Rather than airway driving pressure, the main determinants of respiratory changes in pleural, pericardial and atrial pressure are Vt magnitude and chest wall compliance (both of which determine the compression of the anatomic structures in the cardiac fossa) [14, 15]. Decreased lung compliance during ARDS may therefore have little effect on ΔRESPPP [12]. Last, to avoid respiratory acidosis, reduced Vt is frequently combined with an increased respiratory rate (RR), which may also downplay the performance of ΔRESPPP [16].

Thus, ΔRESPPP may be of interest to guide fluid therapy during ARDS, but several physiological mechanisms may limit its validity. The current literature about its performance in ARDS is scarce, and opposite conclusions have been drawn [10, 17]. We aimed to assess the performance of ΔRESPPP to predict fluid responsiveness in a large population of patients with ARDS.

Materials and methods

ARDS patients from another study were studied [3] and are being partly shared with another study [18]. In the three participating centers (Hôpital Bichat-Claude Bernard, Paris, France; Centre Hospitalier Régional Universitaire of Tours, Tours, France; and Centre Hospitalier Régional of Orléans, Orléans, France), patients were included over the same 18-month period, either after written informed consent was obtained from a relative or after emergency enrollment followed by delayed consent as approved by our regional ethics board.

Patients

Adults with acute circulatory failure (systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg, mean blood pressure <65 mmHg, skin mottling, urine output <0.5 ml/kg/hour, arterial lactate >2.5 mM/l or vasopressor infusion) and ARDS [19] exhibiting a Ramsay sedation scale score >4 and no arrhythmia were included if they were receiving mechanical ventilation in volume-controlled mode without triggering the ventilator.

Patients were not included if they were receiving diuretic treatment, had uncontrolled hemorrhage, were in a state of brain death, were receiving intraaortic balloon pump support, had a risk of fluid loading-induced, life-threatening, hypoxemia (partial pressure of O2 to fraction of inspired O2 ratio (PaO2/FiO2 ratio) <70 mmHg, body weight indexed extravascular lung water (EVLWi) >22 ml-1 kg-1 (PiCCO™ system: Pulsion Medical Systems AG, Munich, Germany), transmural pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (PAOPtm) >22 mmHg (pulmonary artery catheter; Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA)). PAOPtm equals PAOP minus an estimation of the extramural pressure that acts on pulmonary vessels and was calculated as follows: PAOPtm = end expiratory PAOP - [PEEPt × (end inspiratory PAOP - end expiratory PAOP)/(Pplat - PEEPt)]) [20].

The study procedure was stopped in case of changes in respirator settings or vasoactive therapy, occurrence of arrhythmia or respiratory intolerance to volume expansion (EVLWi >22 ml-1 kg-1 or PAOPtm >22 mmHg or 5% decrease in pulse oxymetry (SpO2)). Mechanical ventilation, vasoactive therapy, sedation and paralysis were set by the attending physician and not modified.

Measurements

Hemodynamic (heart rate (HR), blood pressure and cardiac output (CO)) and respiratory parameters (PEEPt, Pplat, RR and Vt) were measured at baseline, immediately after infusion of 300 ml of modified fluid gelatin over 18 minutes (to assess the respiratory tolerance) and an additional 200 ml over 12 minutes.

CO was measured through end-expiratory injection of 10 ml or 15 ml (transcardiac or transpulmonary thermodilution, respectively) of an iced dextrose solution (using a closed injection system with in-line temperature measurement: CO-set+™ system (Edwards Lifesciences) or that which is included in the PiCCO™ system). Three consecutive measurements within 10% (if not, seven measurements) were averaged.

The correct placement of the pulmonary artery catheter was ascertained by visualization of concordant waveforms and calculation of the respiratory changes in PAOP (ΔPAOP)-to-respiratory changes in pulmonary artery pressure (ΔPAP) ratio [21].

Central venous pressure (CVP) (direct reading of the displayed value), PAOP (end-expiratory value measured on frozen waveform) and blood pressure were measured with a disposable transducer (TruWave™; Baxter Division Edwards, Maurepas, France), zeroed at the level of the midaxillary line. Offline, on high-resolution paper tracings, including airway and blood pressure waveforms and after their numerical enlargement, ΔRESPPP was calculated by an observer blinded to other hemodynamic data as follows and averaged over three consecutive respiratory cycles:

within one respiratory cycle [1]. Other indices derived from respiratory changes in arterial pressure were calculated over three consecutive respiratory cycles: the expiratory decrease in systolic pressure (dDown) and the respiratory changes in systolic pressure (SPV) [15].

Echocardiography was performed within 6 hours of measurements to quantify valvular regurgitations and to detect intracardiac shunts or acute cor pulmonale (right-to-left ventricular end-diastolic area ratio above 0.6 with paradoxical septal wall motion).

Statistical analysis

Patients were classified as responders if volume expansion induced an increase in CO ≥10% and as nonresponders otherwise. Indeed, a measured increase of CO above 9% (which we rounded to 10%) reliably reflects that a real change has taken place [22]. To validate this choice of cutoff in our patients (assessment of intermeasurement variability within each set of measurements), we calculated the least significant change (LSC) for each set of CO measurements in each patient at each phase ((1.96√2)CV/√number of measurements within one set) with CV being the coefficient of variation (SD/mean). Thus, we ascertained that each individual patient classified as a responder had a CO increase above LSC [23]. Calculations were also performed using a 15% relative [1, 4] or an absolute 300 ml/min/m2[24] cutoff to define fluid responsiveness.

Variables (expressed as means ± SD or n (%)) were compared using Student's t-test and Fisher's exact test (between responders and nonresponders), paired Student's t-test (for each patient), analysis of variance and the χ2 test (between centers). For each index (ΔRESPPP, SPV and dDown), we calculated the area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUC), determined positive and negative likelihood ratios (LR+ and LR-) for the best cutoff (Youden method) and for the widely used cutoff of 12% for ΔRESPPP [2]. The values of 5 and 10 for LR+ (or 0.2 and 0.1 for LR-) helped to divide the continuous scale of likelihood ratios into three categories: weak, good and strong evidence of discriminative power [25]. AUC values in subgroups of patients were compared [26]. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical tests were two-tailed and performed using MedCalc software (Mariakerke, Belgium) and Statview software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

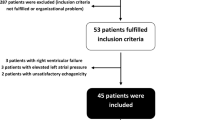

Sixty-five patients were included (Table 1). The mean LSCs of CO measurements were 6.7% and 6.5% at baseline and after volume expansion, respectively, and all responders exhibited individual CO changes from baseline to after volume expansion greater than their individual LSCs. Administration of catecholamine was the sole criterion triggering inclusion in 14 patients (22%): norepinephrine (n = 13, 0.40 ± 0.46 μg/kg/min) or epinephrine (n = 1, 0.26 μg/kg/min). Volume expansion was interrupted in two patients after 300-ml intolerance (one because of a 6% drop in SpO2 and one because of an increased EVLWi >22 ml/kg). Data after 300-ml volume expansion were used for analysis of these two patients. Hemodynamic parameters at baseline and their evolution after volume expansion are detailed in Table 2. The proportion of responders, the Simplified Acute Physiology Score II, baseline mean arterial pressure, HR, CO, and ΔRESPPP were similar between centers (all P > 0.05).

Predictive performance

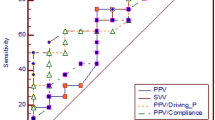

ΔRESPPP was associated with an AUC of 0.75 (95% confidence interval (CI95): 0.62 to 0.85) and a best cutoff value of 5% (LR+ and LR- of 4.8 (CI95: 3.6 to 6.2) and 0.32 (CI95: 0.1 to 0.8), respectively) (Table 3 and Figures 1 and 2). The common 12% cutoff [2, 17] was associated with LR+ and LR- values of 2 (CI95: 0.8 to 4.9) and 0.92 (CI95: 0.3 to 2.8), respectively.

Performance of respiratory changes in pulse pressure (Δ RESP PP) in the whole shocked acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) population ( n = 65). Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve obtained for ΔRESPPP to predict a 10% increase in cardiac output after 500 ml volume expansion. AUC, area under the ROC curve. LR+, positive likelihood ratio. LR-, negative likelihood ratio.

Individual values of baseline static and breath-derived indices in responders and nonresponders. CVP, central venous pressure; PAOP; pulmonary artery occlusion pressure; PAOPtm, transmural pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (see Materials and methods section for details) [20]; ΔRESPPP, respiratory changes in arterial pulse pressure; dDown, expiratory decrease in systolic arterial pressure; SPV, respiratory changes in systolic arterial pressure; AUC, area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve. Responders are defined as patients increasing their cardiac output by at least 10% after a 500-ml volume expansion. The arrows show patients with acute cor pulmonale (see Materials and methods section for definition).

Adjusting ΔRESPPP for various estimates of extramural vascular pressure variations (ΔRESPPP/Pplat, ΔRESPPP/driving pressure, and ΔRESPPP/Vt ratios) did not lead to major improvement in predictive performance (Figure 3). In the 33 carriers of a pulmonary artery catheter, ΔRESPPP/ΔPAP and ΔRESPPP/ΔPAOP were associated with AUCs of 0.79 (CI95: 0.61 to 0.92) and 0.81 (CI95: 0.64 to 0.93), respectively. Figures 2 and 3 show the important overlap of baseline values of each index between responders and nonresponders.

Individual values of baseline respiratory changes in arterial pulse pressure (Δ RESP PP) corrected for surrogates of respiratory variations in pleural pressure. Vt, tidal volume; driving pressure, airway plateau pressure minus total end-expiratory pressure; ΔPAOP: respiratory changes in pulmonary artery occlusion pressure; ΔPAP, respiratory changes in pulmonary artery pressure; AUC, area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve. Responders are defined as patients increasing their cardiac output of at least 10% after 500-ml volume expansion.

With the purpose of identifying a subpopulation in which ΔRESPPP might achieve better results, we performed a subgroup analysis. In case of respiratory variation in PAOP above its median value (>4 mmHg), ΔRESPPP was associated with an AUC of 1 (CI95: 0.73 to 1) as compared with 0.79 (CI95: 0.52 to 0.94) otherwise (P = 0.07), with a marked decrease of the visual overlap of baseline values of ΔRESPPP between responders and nonresponders (Figure 4A). Dividing our whole population according to the median value of airway driving pressure (10 cmH2O) did not lead to marked difference in AUC and/or in the visual overlap (Figure 4B).

Individual values of baseline Δ RESP PP according to volume responsiveness status and to either respiratory change in PAOP (ΔPAOP) or airway driving pressure. For the purpose of this physiological analysis, patients with ultrasonographic signs of acute cor pulmonale were excluded. The central boxes represent the values from the lower to the upper quartile (25th to 75th percentile). The middle line represents the median. ΔRESPPP, respiratory changes in pulse pressure to predict a 10% increase in cardiac output after 500-ml volume expansion; AUC, area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve. (A) Analysis of the 33 patients with a pulmonary artery catheter. Median for respiratory changes in pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (PAOP) was 4 mmHg. Respiratory change in PAOP equals tidal volume (Vt) divided by chest wall compliance (see Additional file 1 for detailed calculations). Therefore, patients represented in the right part of the figure are those combining a higher Vt and lower chest wall compliance. (B) The median airway driving pressure was 10 cmH2O (n = 59).

Overall, ΔRESPPP performed similarly in the subgroups of patients according to respiratory system compliance, norepinephrine dosage, administration of neuromuscular blocking agents (n = 26), site of the arterial catheter (radial (n = 14) or femoral (n = 51)) (Additional file 1). SPV (n = 65), dDown (n = 45), CVP (n = 65), PAOP (n = 33) and PAOPtm (n = 33) were associated with an AUC below 0.78 (Figure 2). All the results were similar when using a 15% relative or a 300 ml/min/m2 absolute cutoff for volume expansion-induced increase in CO to define fluid responsiveness (Table 3 and Additional file 1, Figures S1 and S2). Among the 40 patients whose CVP increased by ≥2 mmHg after 300-ml fluid loading, none of the 28 nonresponders after 300 ml responded to the additional 200-ml fluid loading.

Discussion

The main finding of this large multicenter study of 65 shocked ARDS patients with neither arrhythmia nor spontaneous respiratory activity is that the performance of ΔRESPPP is poor in this clinical situation. Because fluid responsiveness prediction is of utmost importance in ARDS, we attempted unsuccessfully to improve ΔRESPPP performance by (1) its indexation, (2) analyzing different cutoffs for ΔRESPPP or fluid responsiveness definition or (3) identifying subgroups where ΔRESPPP may perform better.

Huang et al.'s study [17], including 22 patients, specifically addressed the issue of ΔRESPPP performance in ARDS and reported a similar AUC (0.77) for ΔRESPPP as in our population (0.75 (CI95: 0.62 to 0.085)). In our study, the AUC was not good, as the lower bound of the 95% confidence interval was below 0.75 [27]. Partly because confidence intervals for AUCs were not reported in Huang et al.'s study [17], it was considered that these authors' conclusion (that ΔRESPPP remains a reliable predictor of fluid responsiveness for ARDS patients ventilated with low Vt and high PEEP) was a misinterpretation [28, 29]. In a large, multicenter population of ARDS patients, our results are similar to those of De Backer et al.[10], who found, in 33 patients (97% ARDS patients) receiving Vt <8 ml/kg, that ΔRESPPP did not perform better than PAOP. Other authors also observed this low performance of ΔRESPPP in case of low Vt. One can reasonably assume that many patients in those studies had ARDS, despite the lack of specific subgroup analysis [11, 30]. Again, the complex pathophysiology of transmission of airway pressure changes to intrathoracic vascular structures [12, 14, 15] justified analyzing specifically the performance of ΔRESPPP in ARDS patients.

Interestingly, our mean ΔRESPPP was low at baseline (5.2%) compared with most studies exhibiting values close to 12% [2] (6% to 10% in ARDS patients [10, 17]). Many causes can be identified to explain this low baseline ΔRESPPP value. First, it may be a consequence of including patients already resuscitated. Indeed, large volume expansion before inclusion (not recorded) may explain the low variations in blood pressure waveform we observed. However, despite this initial resuscitation, 40% of our patients were still fluid responders. Second, as previously shown [7, 8, 10, 11], the low ΔRESPPP may also be related to the low Vt used in our population (6.9 ± 0.95 ml-1 kg-1) compared with other studies reporting values of at least 8 ml-1 kg-1[1, 4, 31–36]. Third, beyond their Vt dependency, breath-related indices also depend on the RR, and more specifically on the HR:RR ratio [16]. Again, our respiratory settings (RR, 24 ± 6/minute; HR:RR ratio, 4.5 ± 1.6) differed from those previously reported, with values ranging from 8 to 17/minute for mean RR and from 5 to 8 for mean HR:RR ratio [8, 31–33, 36]. It is noteworthy that these two limitations of ΔRESPPP (low Vt and high RR) often come together in particular in case of ARDS. Figure 5 illustrates the impact of Vt and HR:RR ratio on ΔRESPPP in our population.

Baseline Δ RESP PP according to Vt and HR:RR ratio. Beyond chest wall compliance, ΔRESPPP is influenced by Vt [10], HR:RR ratio [16] and fluid responsiveness status. This is confirmed in our study population by using a composite index including these respiratory settings: Vt × HR:RR ratio. Two-way analysis of variance disclosed that the product of Vt × HR:RR ratio and the responder versus nonresponder status independently influenced the value of ΔRESPPP (P = 0.0013 and P = 0.0014, respectively). The results of post hoc tests (Fisher's procedure of least significant difference) between quartiles of (Vt × HR:RR ratio) are shown. With regard to the need for this physiological analysis, patients with ultrasonographic evidence of acute cor pulmonale (n = 4) were excluded. Vt, tidal volume; HR, heart rate. RR, respiratory rate; ΔRESPPP, respiratory changes in pulse pressure. Responders are defined as those patients with a 10% increase in cardiac output after 500-ml volume expansion. The central boxes represent the values from the lower to the upper quartile (25th to 75th percentile). The middle line represents the median value.

Beyond these limitations (low Vt and high RR) causing false-negative cases of ΔRESPPP, false-positive cases may also arise because of a common phenomenon during ARDS: pulmonary artery hypertension [37, 38] and/or right ventricular dysfunction [39]. We only searched for marked ultrasonographic signs of acute cor pulmonale (arrows in Figure 1). Performing more sophisticated measurements of right ventricular function (for example, peak systolic velocity of tricuspid annular motion) would have sensitized the detection of this restriction for ΔRESPPP usefulness [39]. It is noteworthy that pulmonary artery hypertension and/or right ventricular failure may be an even more frequent limitation of ΔRESPPP in case of later or more severe ARDS (PaO2/FiO2 <70) than patients whom we included.

Moreover, changes in chest wall compliance may also affect ΔRESPPP, positively or negatively. Decreased chest wall compliance, observed in cases of intraabdominal hypertension (extrapulmonary ARDS) [40] increases respiratory pleural pressure variations for a given Vt [14, 15]. Thus, ΔRESPPP may be higher and present false-positive results in this situation. At the opposite, chest wall compliance may be increased through the use of muscle relaxants, which was the case in 40% of our patients, and then induce reduced intrathoracic pressure swings and therefore potential false-negative ΔRESPPP results. The lack of measurement of chest wall compliance in our patients (that is, no esophageal pressure measurement) precluded precise analysis of this factor. Nevertheless, using PAOP as a surrogate for esophageal pressure measurements, we performed some physiological analysis which allowed us to gain some insight into this issue.

Our findings do not confirm the hypothesis according to which, owing to ARDS-induced decrease in lung compliance, a small Vt (<8 ml/kg) may cause sufficient changes in intrathoracic pressure, allowing ΔRESPPP to perform well in this population [13]. Actually, ARDS-induced increase in lung stiffness is indeed associated with an increased airway driving pressure (by increased Pplat) for a given Vt [14], but the primary determinants of pleural pressure variations (and then of ΔRESPPP) have been shown to be the magnitude of Vt and chest wall compliance (both of them ruling the compression of the cardiovascular structures), regardless of lung compliance [14]. Indeed, using changes in PAOP as a surrogate for pleural pressure variations [41], we found that ΔRESPPP tended to perform markedly better in patients with high ΔPAOP (Figure 4A), illustrating the importance of high Vt and low chest wall compliance for ΔRESPPP to be useful. Indeed, in our analysis (with the limits of using ΔPAOP as a surrogate), respiratory changes in PAOP represent the ratio of Vt/chest wall compliance (detailed calculation in Additional file 1).

The rather good AUC (0.81 (CI95: 0.64 to 0.93)) that we found for ΔRESPPP/ΔPAOP (in the subset of Swan-Ganz catheter carriers) suggests that a more precise approach of pleural pressure swings may be a more interesting way to correct the crude ΔRESPPP and to improve its predictive ability. Not surprisingly, and as previously reported in case of low Vt [11], no improvement was observed in ΔRESPPP performance when it was corrected for airway driving pressure. Moreover, there was no marked evidence of better performance of ΔRESPPP in cases of high airway driving pressure (Figure 4B), reminding us that this parameter is not a major determinant of ΔRESPPP.

Our ARDS patients exhibited higher values of respiratory system static compliance (total of lung and chest wall compliance) than values usually reported in ARDS patients (40 versus 26 to 30 ml/cmH2O) [10, 17, 42]. There are three potential explanations for this difference: (1) because the PEEP level was not fixed by protocol, some patients may have had PEEP levels high enough to optimize recruitment and respiratory compliance [42]; (2) patients were studied at the early phase of ARDS (Table 1), and lung compliance is classically lower in late ARDS; and 3) we did not include the patients with the most severe cases of ARDS (PaO2:FiO2 ratio <70) for safety reasons. Of note, ΔRESPPP showed similar performance in patients with respiratory system static compliance below or above its median value (Additional file 1), preventing the use of this parameter to identify patients in whom ΔRESPPP might perform better. Because of higher respiratory system compliance, our airway driving pressure was in the lower reported range (13.7 versus 14 to 17 cmH2O) [10, 17, 42]. However, our mean Vt value was slightly higher (6.9 versus 6.3 to 6.4 ml/kg) [10, 17, 42]. Again, as ΔRESPPP is mostly influenced by the Vt rather than the airway driving pressure [7, 10, 14], one would have expected even better performance of ΔRESPPP than that reported in similar previous works.

In our population, the best cutoff value for ΔRESPPP was 5%, that is, close to that previously reported in ARDS patients with low Vt [10]. Another explanation for the poor ability of ΔRESPPP to predict fluid responsiveness may be that this low cutoff exposes it to errors in measurements because of low signal-to-noise ratio [12]. Of note, numerical recordings of ΔRESPPP in ARDS patients [10, 17] did not lead to better performance than using high-resolution paper tracings, as we did.

For the same reasons developed for ΔRESPPP, we found that the other breath-related, blood pressure-derived indices, dDown and SPV, were of similar poor performance in predicting fluid responsiveness in our ARDS population. Before using fluid responsiveness prediction tools, one has to identify patients who may actually benefit from having their CO increased by fluids. In an overall population, many fluid responders actually do not need any fluids (that is, no need for an increase in CO). All of our patients were in acute circulatory failure and most presented signs of tissular hypoperfusion (oliguria in 34%, mottled skin in 34% and hyperlactatemia in 38%), suggesting that they may benefit from volume expansion, but baseline CVP (11 ± 4 mmHg) and PAOP (12 ± 4 mmHg) were unhelpful (Figure 2) [43]. It is precisely in these patients, that is, those with persistent circulatory failure despite initial resuscitation, that other indices are required; but ΔRESPPP is disappointing in patients with ARDS. In this situation, a fluid challenge may be performed [44]. Thus, during volume expansion, an increase in CVP ≥2 mmHg is considered to reflect that the Frank-Starling mechanism of the heart has been tested [43]. Interestingly, among the 40 patients who fulfilled this CVP change criterion after 300-ml volume expansion, none of the 28 nonresponder patients responded after 300 ml to the additional 200-ml volume expansion. Therefore, performing careful fluid challenges while monitoring both CVP and CO may be a safe way to limit undue fluid loading during ARDS.

Conclusions

In our population of patients with early ARDS who were receiving protective mechanical ventilation, partly because of insufficient changes in pleural pressure, ΔRESPPP performed poorly in predicting fluid responsiveness. Fluid management in patients with ARDS may rely on fluid challenges.

Key messages

-

Respiratory variations of pulse pressure (ΔRESPPP) perform poorly in predicting fluid responsiveness in patients with ARDS.

-

Both low tidal volume (by decreasing respiratory pleural pressure changes) and low HR:RR ratio downplay the performance of ΔRESPPP.

-

Respiratory changes in pleural pressure, but not airway driving pressure, are the main determinant of ΔRESPPP.

-

No simple means of improving ΔRESPPP performance was found.

-

Because optimal fluid management is of utmost importance in ARDS patients, clinicians have to rely on other means, such as fluid challenges, for this purpose.

Abbreviations

- ΔRESPPP:

-

respiratory variations in pulse pressure

- ΔPAP:

-

respiratory changes in pulmonary artery pressure

- ΔPAOP:

-

respiratory changes in pulmonary artery occlusion pressure

- ARDS:

-

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- AUC:

-

area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve

- CO:

-

cardiac output

- CVP:

-

central venous pressure

- dDown:

-

difference between the average, over three consecutive respiratory cycles, of the minimal value of systolic blood pressure during a respiratory cycle and the value of systolic blood pressure during apnea

- HR:

-

heart rate

- LR+:

-

positive likelihood ratio

- LR:

-

negative likelihood ratio

- LSC:

-

least significant change

- PAOP:

-

pulmonary artery occlusion pressure

- PAOPtm:

-

transmural pulmonary artery occlusion pressure

- PEEP:

-

positive end-expiratory pressure

- Pplat:

-

plateau pressure

- RR:

-

respiratory rate

- SPV:

-

respiratory changes in systolic arterial pressure over three consecutive respiratory cycles

- Vt:

-

tidal volume.

References

Michard F, Boussat S, Chemla D, Anguel N, Mercat A, Lecarpentier Y, Richard C, Pinsky MR, Teboul JL: Relation between respiratory changes in arterial pulse pressure and fluid responsiveness in septic patients with acute circulatory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000, 162: 134-138.

Marik PE, Cavallazzi R, Vasu T, Hirani A: Dynamic changes in arterial waveform derived variables and fluid responsiveness in mechanically ventilated patients: a systematic review of the literature. Crit Care Med 2009, 37: 2642-2647. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a590da

Lakhal K, Ehrmann S, Runge I, Benzekri-Lefèvre D, Legras A, Dequin PF, Mercier E, Wolff M, Régnier B, Boulain T: Central venous pressure measurements improve the accuracy of leg raising-induced change in pulse pressure to predict fluid responsiveness. Intensive Care Med 2010, 36: 940-948. 10.1007/s00134-010-1755-2

Monnet X, Rienzo M, Osman D, Anguel N, Richard C, Pinsky MR, Teboul JL: Passive leg raising predicts fluid responsiveness in the critically ill. Crit Care Med 2006, 34: 1402-1407. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000215453.11735.06

Malhotra A: Low-tidal-volume ventilation in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2007, 357: 1113-1120. 10.1056/NEJMct074213

Heart National, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network, Wiedemann HP, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, Thompson BT, Hayden D, deBoisblanc B, Connors AF Jr, Hite RD, Harabin AL: Comparison of two fluid-management strategies in acute lung injury. N Engl J Med 2006, 354: 2564-2575. 10.1056/NEJMoa062200

Reuter DA, Bayerlein J, Goepfert MS, Weis FC, Kilger E, Lamm P, Goetz AE: Influence of tidal volume on left ventricular stroke volume variation measured by pulse contour analysis in mechanically ventilated patients. Intensive Care Med 2003, 29: 476-480.

Charron C, Fessenmeyer C, Cosson C, Mazoit JX, Hebert JL, Benhamou D, Edouard AR: The influence of tidal volume on the dynamic variables of fluid responsiveness in critically ill patients. Anesth Analg 2006, 102: 1511-1517. 10.1213/01.ane.0000209015.21418.f4

Renner J, Cavus E, Meybohm P, Tonner P, Steinfath M, Scholz J, Lutter G, Bein B: Stroke volume variation during hemorrhage and after fluid loading: impact of different tidal volumes. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2007, 51: 538-544. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2007.01282.x

De Backer D, Heenen S, Piagnerelli M, Koch M, Vincent JL: Pulse pressure variations to predict fluid responsiveness: influence of tidal volume. Intensive Care Med 2005, 31: 517-523. 10.1007/s00134-005-2586-4

Vallée F, Richard JC, Mari A, Gallas T, Arsac E, Verlaan PS, Chousterman B, Samii K, Genestal M, Fourcade O: Pulse pressure variations adjusted by alveolar driving pressure to assess fluid responsiveness. Intensive Care Med 2009, 35: 1004-1010. 10.1007/s00134-009-1478-4

Lefrant JY, De Backer D: Can we use pulse pressure variations to predict fluid responsiveness in patients with ARDS? Intensive Care Med 2009, 35: 966-968. 10.1007/s00134-009-1479-3

Teboul JL, Vieillard-Baron A: Clinical value of pulse pressure variations in ARDS: still an unresolved issue? Intensive Care Med 2005, 31: 499-500. 10.1007/s00134-005-2587-3

Romand JA, Shi W, Pinsky MR: Cardiopulmonary effects of positive pressure ventilation during acute lung injury. Chest 1995, 108: 1041-1048. 10.1378/chest.108.4.1041

Perel A, Pizov R, Cotev S: Systolic blood pressure variation is a sensitive indicator of hypovolemia in ventilated dogs subjected to graded hemorrhage. Anesthesiology 1987, 67: 498-502. 10.1097/00000542-198710000-00009

De Backer D, Taccone FS, Holsten R, Ibrahimi F, Vincent JL: Influence of respiratory rate on stroke volume variation in mechanically ventilated patients. Anesthesiology 2009, 110: 1092-1097. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819db2a1

Huang CC, Fu JY, Hu HC, Kao KC, Chen NH, Hsieh MJ, Tsai YH: Prediction of fluid responsiveness in acute respiratory distress syndrome patients ventilated with low tidal volume and high positive end-expiratory pressure. Crit Care Med 2008, 36: 2810-2816. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318186b74e

Lakhal K, Ehrmann S, Runge I, Legras A, Dequin PF, Mercier E, Wolff M, Régnier B, Boulain T: Tracking hypotension and dynamic changes in arterial blood pressure with brachial cuff measurements. Anesth Analg 2009, 109: 494-501. 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181a8d83a

Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, Carlet J, Falke K, Hudson L, Lamy M, Legall JR, Morris A, Spragg R: The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS: definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994, 149: 818-824.

Teboul JL, Pinsky MR, Mercat A, Anguel N, Bernardin G, Achard JM, Boulain T, Richard C: Estimating cardiac filling pressure in mechanically ventilated patients with hyperinflation. Crit Care Med 2000, 28: 3631-3636. 10.1097/00003246-200011000-00014

Teboul JL, Besbes M, Andrivet P, Axler O, Douguet D, Zelter M, Lemaire F, Brun-Buisson C: A bedside index assessing the reliability of pulmonary occlusion pressure measurements during mechanical ventilation with positive end-expiratory pressure. J Crit Care 1992, 7: 22-29. 10.1016/0883-9441(92)90005-R

Ostergaard M, Nilsson LB, Nilsson JC, Rasmussen JP, Berthelsen PG: Precision of bolus thermodilution cardiac output measurements in patients with atrial fibrillation. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2005, 49: 366-372. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2005.00613.x

Lodder MC, Lems WF, Ader HJ, Marthinsen AE, van Coeverden SC, Lips P, Netelenbos JC, Dijkmans BA, Roos JC: Reproducibility of bone mineral density measurement in daily practice. Ann Rheum Dis 2004, 63: 285-289. 10.1136/ard.2002.005678

Magder S, Bafaqeeh F: The clinical role of central venous pressure measurements. J Intensive Care Med 2007, 22: 44-51. 10.1177/0885066606295303

Grimes DA, Schulz KF: Refining clinical diagnosis with likelihood ratios. Lancet 2005, 365: 1500-1505. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66422-7

Hanley JA, McNeil BJ: The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 1982, 143: 29-36.

Ray P, Le Manach Y, Riou B, Houle TT: Statistical evaluation of a biomarker. Anesthesiology 2010, 112: 1023-1040. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181d47604

Journois D, Squara P: Back to "belief-based medicine" because of receiver operating characteristic curves? Crit Care Med 2009, 37: 1532-1533. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819d2f26

Payen D, Vallée F, Mari A, Richard JC, De Backer D: Can pulse pressure variations really better predict fluid responsiveness than static indices of preload in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome? Crit Care Med 2009, 37: 1178. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181986f85

Muller L, Louart G, Bousquet PJ, Candela D, Zoric L, de La Coussaye JE, Jaber S, Lefrant JY: The influence of the airway driving pressure on pulsed pressure variation as a predictor of fluid responsiveness. Intensive Care Med 2010, 36: 496-503. 10.1007/s00134-009-1686-y

Vieillard-Baron A, Chergui K, Rabiller A, Peyrouset O, Page B, Beauchet A, Jardin F: Superior vena caval collapsibility as a gauge of volume status in ventilated septic patients. Intensive Care Med 2004, 30: 1734-1739.

Cannesson M, Attof Y, Rosamel P, Desebbe O, Joseph P, Metton O, Bastien O, Lehot JJ: Respiratory variations in pulse oximetry plethysmographic waveform amplitude to predict fluid responsiveness in the operating room. Anesthesiology 2007, 106: 1105-1111. 10.1097/01.anes.0000267593.72744.20

Cannesson M, Slieker J, Desebbe O, Farhat F, Bastien O, Lehot JJ: Prediction of fluid responsiveness using respiratory variations in left ventricular stroke area by transoesophageal echocardiographic automated border detection in mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care 2006, 10: R171. 10.1186/cc5123

Hofer CK, Müller SM, Furrer L, Klaghofer R, Genoni M, Zollinger A: Stroke volume and pulse pressure variation for prediction of fluid responsiveness in patients undergoing off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. Chest 2005, 128: 848-854. 10.1378/chest.128.2.848

Kramer A, Zygun D, Hawes H, Easton P, Ferland A: Pulse pressure variation predicts fluid responsiveness following coronary artery bypass surgery. Chest 2004, 126: 1563-1568. 10.1378/chest.126.5.1563

Preisman S, Kogan S, Berkenstadt H, Perel A: Predicting fluid responsiveness in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: functional haemodynamic parameters including the Respiratory Systolic Variation Test and static preload indicators. Br J Anaesth 2005, 95: 746-755. 10.1093/bja/aei262

Daudel F, Tüller D, Krähenbühl S, Jakob SM, Takala J: Pulse pressure variation and volume responsiveness during acutely increased pulmonary artery pressure: an experimental study. Crit Care 2010, 14: R122. 10.1186/cc9080

Wyler von Ballmoos M, Takala J, Roeck M, Porta F, Tueller D, Ganter CC, Schröder R, Bracht H, Baenziger B, Jakob SM: Pulse-pressure variation and hemodynamic response in patients with elevated pulmonary artery pressure: a clinical study. Crit Care 2010, 14: R111. 10.1186/cc9060

Mahjoub Y, Pila C, Friggeri A, Zogheib E, Lobjoie E, Tinturier F, Galy C, Slama M, Dupont H: Assessing fluid responsiveness in critically ill patients: false-positive pulse pressure variation is detected by Doppler echocardiographic evaluation of the right ventricle. Crit Care Med 2009, 37: 2570-2575. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a380a3

Ranieri VM, Brienza N, Santostasi S, Puntillo F, Mascia L, Vitale N, Giuliani R, Memeo V, Bruno F, Fiore T, Brienza A, Slutsky AS: Impairment of lung and chest wall mechanics in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: role of abdominal distension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997, 156: 1082-1091.

Bellemare P, Goldberg P, Magder SA: Variations in pulmonary artery occlusion pressure to estimate changes in pleural pressure. Intensive Care Med 2007, 33: 2004-2008. 10.1007/s00134-007-0842-5

Briel M, Meade M, Mercat A, Brower RG, Talmor D, Walter SD, Slutsky AS, Pullenayegum E, Zhou Q, Cook D, Brochard L, Richard JC, Lamontagne F, Bhatnagar N, Stewart TE, Guyatt G: Higher vs lower positive end-expiratory pressure in patients with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2010, 303: 865-873. 10.1001/jama.2010.218

Antonelli M, Levy M, Andrews PJ, Chastre J, Hudson LD, Manthous C, Meduri GU, Moreno RP, Putensen C, Stewart T, Torres A: Hemodynamic monitoring in shock and implications for management. International Consensus Conference, Paris, France, 27-28 April 2006. Intensive Care Med 2007, 33: 575-590. 10.1007/s00134-007-0531-4

Vincent JL, Weil MH: Fluid challenge revisited. Crit Care Med 2006, 34: 1333-1337. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000214677.76535.A5

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Projet Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique grant PHRC R10-5, centre hospitalier d'Orléans, France, September 2004.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

KL, SE and TB contributed to the conception and design of the study. KL, SE, DBL, IR, EM, PFD, AL and TB contributed to the acquisition of data. KL, SE, MW, BR and TB contributed to the drafting and revision of the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

13054_2011_9354_MOESM1_ESM.DOC

Additional file 1: Additional data and figures. Impact of several clinical factors on the performance of ΔRESPPP: subgroup comparisons according to respiratory system compliance, norepinephrine dosage, neuromuscular blocking agent use and site of the artery catheter. Impact of the definition of fluid responsiveness on the performance of ΔRESPPP, individual values of baseline static and breath-derived indices in responders and nonresponders using the 15% cutoff for cardiac output to define fluid responsiveness, performance of ΔRESPPP using the 15% cutoff for cardiac output to define fluid responsiveness. Impact of chest wall compliance on ΔRESPPP provides additional comments to Figure 4. AUC, area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve; ΔRESPPP, respiratory changes in pulse pressure. (DOC 122 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Lakhal, K., Ehrmann, S., Benzekri-Lefèvre, D. et al. Respiratory pulse pressure variation fails to predict fluid responsiveness in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care 15, R85 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc10083

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc10083