Abstract

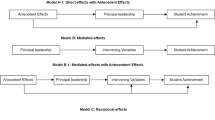

This mixed-method study examines Arizona principals’ capacity-building skills and practices in Tier III schools aimed at developing potential for sustained improvements in student outcomes. Data sources included surveys (62 individuals) and semistructured interviews (29 individuals) of principals and staff (e.g. teachers, instructional coaches, assistant principals) who participated in grant-funded leadership training over an 18-month period. The theoretical framework consisted of leadership in the sociocultural dimension (Ylimaki et al. in Leadersh Policy Sch 11(2):168–193, 2012) and capacity building for sustainable improvement in high-capacity Schools (Mitchell and Sackney in Sustainable improvement: building learning communities that endure. Sense Publishers, Rotterdam, 2009). Findings indicated that: (1) schools were not at high-levels of capacity building; (2) those schools in process of building capacity for sustainable improvement demonstrate a directive leadership approach; (3) school development towards high capacity focused on micro-level processes (e.g., professional learning communities); and (4) little attention was given to leadership in the socio-cultural dimension. Implications of the study suggest future research test a leadership development model for Tier III schools that links capacity building leadership and student achievement. The next generation of educational leaders must also have the knowledge, skills, dispositions, and analytical tools to lead schools in both the accountability culture and the macro socio-cultural dimension.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

AIMS is the Arizona state standards-based assessment that measures student proficiency of the Arizona Academic Content Standards in Writing, Reading, Mathematics, and Science and is required by state and federal law (Arizona Department of Education 2012a).

Tier III schools are distinct from Tier I or II schools. Tier I schools are among the lowest-achieving 5 % of Title I schools and had a graduation rate below 60 %. Tier 2 consists of secondary schools with graduation rates below 60 %, among the lowest achieving 5 %, and eligible for Title I funds but did not receive them (Arizona Department of Education 2012d).

According to a US Census (2009) report, the percentage of Arizona population with Hispanic or Latino origin is 30.8 %. American Indian and Alaska Native persons count 4.9 % of Arizona population, significantly more than the national parameter of 1.0 %. The percentage of White not Hispanic population in Arizona is 57.3 %, lower than that national data of 65.1 %. The percentages of other ethnicities in the Arizona population are 4.4 % Black or African American, 2.6 % Asian, .2 % Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, and 1.8 % reporting two or more races (US Census 2009).

Public schools in the US are classified by their level of academic performance as defined by the states in which they are located. For example, Arizona uses letter grades for performance labels (Arizona Department of Education 2012d).

Arizona high schools are required to comply with language requirements as part of accountability expectations (e.g. English only, 4-h English Language Development block for English Language Learners; Rios-Aguilar et al. 2010).

For more about funds of knowledge, please see Moll et al. (1992).

For more about the ethic of community, please see Furman (2004).

The other 190 schools qualified for school improvement grants, were reconstituted, or were placed in official turnaround status prior to the beginning of the study.

The location of schools within the statewide Tier III sample (N = 252) consists of 35 % rural, 24 % urban, and 41 % suburban (Arizona Department of Education 2012b).

The authors added a section on both teacher and principal surveys to query participants about their level of assessment literacy.

Assistant principals were asked to take staff surveys as respondents reflected on the principal and the contributions of her/his practice.

Both principal and staff surveys consisted of the same 137 Likert-scale items.

Additional principal survey items contained Likert-scale responses.

A Pearson’s Chi squared test is the more statistically valid test than an independent samples t test to compare means because Likert-scale items assume a discrete distribution rather than a normal distribution (Field 2009). Likert-scale response items on five categories (low to high) can only take on certain values (‘1’ through ‘5’) on a scale. Independent samples t-tests compare means that have continuous scales. The expected frequencies in all categories of Likert-scale items failed to meet minimum requirements. Expected frequencies should always be greater than 5 (Field 2009).

Low capacity is indicated by survey Likert-type items with a mean score of ‘1’ or ‘2’ on a 5-point scale. Medium capacity is indicated by a mean score of ‘3’.

High capacity is indicated by survey Likert-type items with a mean score of a ‘4’ or ‘5’ on a 5-point scale.

Since we were not able to conduct chi-squared tests due to the expected frequencies not meeting the number of minimum requirements, we determined significant meant at least a mean difference of .5 or more between principals and staff responses on Likert-scale items.

The mean and standard deviation for principals is noted by a subscript p and subscript s for staff.

We reasoned that a mean difference of .5 or more suggested considerable disagreement when participant groups (principals, teachers), on average, identified with two different categories or responses.

We considered, in some instances, a staff mean of 3.9 as ‘high capacity’ when the principal mean was at least a ‘4’ and the mean difference was less than .5.

In this case, mean scores in ‘1’ or ‘2’ categories indicate low feelings of tension about these items.

References

Apple, M. (1996). Cultural politics and education. New York, NY: TC Press.

Apple, M. (2000). Teachers and texts: A political economy of class and gender relations in education. New York, NY: Routledge.

Apple, M. (2004). Ideology and curriculum. New York, NY: Routledge.

Arizona Department of Education. (2010). Corrective action and restructuring support planning process. Retrieved from http://www.azed.gov/wp-content/uploads/PDF/CA-RPFallProcessFINAL82310.pdf.

Arizona Department of Education. (2012a). Assessment: Overview. Retrieved from http://www.azed.gov/standards-development-assessment/.

Arizona Department of Education. (2012b). Research and evaluation: October 1st enrollment figures. Retrieved from http://www.azed.gov/research-evaluation/arizona-enrollment-figures/.

Arizona Department of Education. (2012c). School improvement: Overview. Retrieved from http://www.azed.gov/improvement-intervention/.

Arizona Department of Education. (2012d). State of Arizona Department of Education 2011–2012 state report card. Retrieved from http://www.azed.gov/research-evaluation/files/2011/07/2012statereportcard.pdf.

Arizona Department of Education. (2012e). Research and evaluation: A–F accountability. Retrieved from http://www.azed.gov/research-evaluation/.

Ariz. Rev. Stat. §15-203(A) (38).

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

Day, C. (2009). Capacity-building through layered leadership: Sustaining the turnaround. In A. Harris (Ed.), Distributed leadership: Different perspectives, studies in educational leadership (Vol. 7, pp. 121–137). Dordrecht: Springer.

Field, (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Furman, G. (2004). The ethic of community. Journal of Educational Administration, 42(2), 215–235.

Jacobson, S., Johnson, L., Ylimaki, R., & Giles, C. (2005). Successful school leadership in changing times: Cross-national findings in the third year of an international research project. Journal of Educational Administration, 43(6), 607–618.

Johnson, L. (2007). Rethinking successful school leadership in challenging US schools: Culturally responsive practices in school-community relationships. International Studies in Educational Administration, 35(3), 49–57.

Johnson, L., Møller, J., Pashiardis, P., Vedøy, G., & Savvides, V. (2011). Culturally responsive practices (pp. 75-102). In R. Ylimaki & S. Jacobson (Eds.), US and cross-national policies, practices, and preparation: Implications for successful instructional leadership, organizational learning, and culturally responsive practices. Dordrecht: Springer.

Leithwood, K., & Riehl, C. (2003). What do we already know about successful school leadership? Paper prepared for the AERA Division A Task Force on Developing Research in Educational Leadership.

Leithwood, K., & Riehl, C. (2005). What we know about successful school leadership. In W. Firestone & C. Riehl (Eds.), A New Agenda: Directions for research on educational leadership (pp. 22–47). New York: Teachers College Press.

Merriam, S. B. (1988). Case study research in education: A qualitative approach. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Merriam, S. B. (2001). Case studies as qualitative research. In C. F. Conrad, J. G. Haworth, & L. R. Lattuca (Eds.), Qualitative research in higher education (pp. 191–200). Boston, MA: Pearson Custom Publishing.

Mitchell, C., & Sackney, L. (2009). Sustainable improvement: Building learning communities that endure. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Moll, L., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & Gonzalez, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory into Practice, 31(2), 132–141.

No Child Left Behind (NCLB). (2002). Act of 2001, Pub. L. No. 107–110, §115, Stat. 1425.

Rios-Aguilar, C., Gonzalez-Canche, M., & Moll, L. C. (2010). Implementing structured English immersion in Arizona: Benefits, costs, challenges, and opportunities. Retrieved from http://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/language-minority-students/implementing-structured-englishimmersion-sei-in-arizona-benefits-costs-challenges-and-opportunities.

Seashore-Louis, K., Leithwood, K., Wahlstrom, K. L., Anderson, S. E., Michlin, M., Mascall, B. et al. (2010). Investigating the links to student learning: Final report of research findings. Retrieved from http://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/school-leadership/key-research/Documents/Investigating-the-Links-to-Improved-Student-Learning.pdf.

US Census (2009). U.S. census data: Race, ethnicity, and poverty. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov.

US Department of Education. (2009). Race to the Top executive summary. Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/programs/racetothetop/executive-summary.pdf.

Ylimaki, R., & Brunner, C. C. (2011). Power and collaboration-consensus/conflict in curriculum leadership: Status-quo or change? American Educational Research Journal, 48(6), 1258–1285.

Ylimaki, R., Bennett, J., Fan, J., & Villaseñor, E. (2012). Notions of ‘success’ in Southern Arizona schools: Principal leadership in changing demographic and border contexts. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 11(2), 168–193.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bennett, J.V., Ylimaki, R.M., Dugan, T.M. et al. Developing the potential for sustainable improvement in underperforming schools: Capacity building in the socio-cultural dimension. J Educ Change 15, 377–409 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-013-9217-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-013-9217-6