Abstract

Social security contributions in most countries are split between employers and employees. According to standard incidence analysis, social security contributions affect employment negatively, but it is irrelevant how they are divided between employers and employees. This paper considers the possibility that (i) workers perceive a linkage between current contributions and future benefits, and (ii) they value employer’s contributions less than own contributions, as the former are less “salient.” Under these assumptions, I find that employers’ contributions have a stronger (negative) effect on employment than employees’ contributions. Furthermore, a change in how contributions are divided, which reduces the share of employers, is beneficial for employment. Finally, making employers’ contributions more visible to workers also has a positive effect on employment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Fullerton and Metcalf (2002).

Statutory incidence matters for real incidence when there is a (binding) minimum price.

In another survey conducted by the same authors in Germany and Italy, only 20 % of respondents know the overall (employer plus employee) contribution rate approximately. See Tabellini et al. (2002).

See (Domínguez et al. 2011).

There are countries in which workers also receive information on contributions paid by their employers. In the USA, workers get this information in their Social Security Statements. Unfortunately, the Social Security Administration has recently decided to stop mailing the statements due to budgetary restrictions.

See also Mulligan and Sala-i-Martin (1999).

This model can be seen as a reduced-form of a standard intertemporal labor decision model.

This is similar to Saez et al. (2012).

Using my notation, (Gruber 1997) defines labor supply as:

$$\begin{aligned} S=S((1-a\tau _{W})w+q\tau _{F}w), \end{aligned}$$where \(a\) and \(q\) reflect how workers discount their contributions relative to cash income and how they value employer’s contributions relative to cash income, respectively. I get my formulation by setting \(a=1-\delta ,\) and \( q=\delta \varphi .\)

To check this, note that we need \(1\ge \tau _{W}(1-\delta )+\delta \varphi .\) The term on the right reaches a global maximum when \(\delta =\varphi =1,\) in which case its value is 1. In all other cases, its value is below 1.

Note that Condition (7) is both necessary and sufficient. That is, if \(\varphi >\widehat{\varphi },\) we have that \(\left| \frac{d\ln L}{ d\tau _{F}}\right| <\left| \frac{d\ln L}{d\tau _{W}}\right| .\) However, in this case the difference between both terms is approximately zero as long as both \(\tau _{W}\) and \(\tau _{F}\) are small. In fact, the difference at the minimum (\(\delta =0)\) is:

$$\begin{aligned} \left| \frac{d\ln L}{d\tau _{F}}\right| -\left| \frac{d\ln L}{ d\tau _{W}}\right| =\frac{-\tau \varepsilon _{D}\varepsilon _{S}}{ (1-\tau _{W})\varepsilon _{S}+(1+\tau _{F})\varepsilon _{D}}, \end{aligned}$$which is close to zero when \(\tau \) is small. This is the standard result saying that the effect of an increase in \(\tau _{F}\) is equal to the effect of an increase in \(\tau _{W}\), since economic incidence is determined only by the elasticities of supply and demand.

If \(\delta <\frac{\tau }{1+\tau },\) then \(\widehat{\varphi }<0.\)

We can compute easily:

$$\begin{aligned} \left. \frac{d(w_{F}L)}{d\tau _{F}}\right| _{\overline{T}}=w_{F}L\left( \frac{\varepsilon _{S}\delta (1-\varphi )}{\alpha \varepsilon _{S}+(1+\tau _{F})\varepsilon _{D}}\frac{1}{1+\tau _{F}}\right) (1-\varepsilon _{D}). \end{aligned}$$If \(\delta =0,\) the term \(\left. \frac{d\ln w}{d\tau _{F}}\right| _{ \overline{\tau }}\) is approximately -1, as long as \(\tau _{W}\) and \(\tau _{F} \) are not very large. This is the classical result of full shifting where the equilibrium wage depends only on the value of \(\tau ,\) and not on how this tax is split between employers and employees. Additionally, when \( \delta =0\) both \(\left. \frac{d\ln w_{F}}{d\tau _{F}}\right| _{\overline{ \tau }}\) and \(\left. \frac{d\ln L}{d\tau _{F}}\right| _{\overline{\tau } } \) are approximately zero as long as \(\tau \) is small. As long as total tax \(\tau \) does not change, labor costs \(w_{F}\) and employment \(L\) are not affected by how contributions are split between worker and firm. It does not matter who bears the statutory burden of the tax.

See Mastrobuoni (2011).

In the context of the MP model of Sect. 3, this policy change has always the effect of reducing the equilibrium level of unemployment. The reason is that it only affects the wage curve, shifting it to the right, while it does not affect the job creation curve.

References

Boeri, T., Börsch-Supan, A., & Tabellini, G. (2001). Would you like to shrink the welfare state? A survey of European citizens. Economic Policy, 16(32), 7–50.

Buchanan, J., & Wagner, R. (1977). Democracy in deficit. New York: Academic Press.

Cabral, M. & Hoxby C. (2012). The hated property tax: salience, tax rates, and tax revolts, NBER Working Paper 18514.

Chetty, R. (2009). The simple economics of salience and taxation, NBER Working Papers No. 15246.

Chetty, R., Looney, A., & Kroft, K. (2009). Salience and taxation: Theory and evidence. American Economic Review, 99(4), 1145–1177.

Domínguez, I., Devesa, E., Devesa, M., Encinas, B., Meneu, R., & Nagore, A. (2011). Encuesta para determinar el impacto de las reformas necesarias del sistema de pensiones español. In Necesitan los futuros jubilados españoles complementar su pensión? Análisis de las reformas necesarias y sus efectos sobre la decisión de los ciudadanos (Part III). Fundación Edad y Vida. http://www.edad-vida.org/fitxers/publicacions/Necesitan%20Jubilados.pdf

Dušek, L. (2002). Visibility of Taxes and the Size of Government, Working Paper.

Feldstein, M., & Liebman, J. B. (2002). Social security. In A. J. Auerbach & M. Feldstein (Eds.), Handbook of public economics (Vol. IV, pp. 2245–2324). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Finkelstein, A. (2009). E-Z tax: Tax salience and tax rates. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(3), 969–1010.

Fullerton, D., & Metcalf, G. (2002). Tax incidence. In A. J. Auerbach & M. Feldstein (Eds.), Handbook of public economics (Vol. IV, pp. 1787–1872). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Goldin, J., & Homonoff, T. (2013). Smoke gets in your eyes: Cigarette tax salience and regressivity. American Economic Journal, 5(1), 302–306.

Goldin, J. (2013). Optimal tax salience. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Gruber, J. (1997). The incidence of payroll taxation: Evidence from Chile. Journal of Labor Economics, 15(3), s72–s101.

Hamermesh, D. S. (1993). Labour demand elasticity. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Koskela, E., & Schöb, R. (1999). Does the composition of wage and payroll taxes matter under nash bargaining? Economics Letters, 64, 343–349.

Lindbeck, A., Molander, P., Persson, T., Petersson, O., Sandmo, A., Swedenborg, B., et al. (1994). Turning Sweden around. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Mastrobuoni, G. (2011). The role of information for retirement behavior: Evidence based on the stepwise introduction of the social security statement. Journal of Public Economics, 95, 913–925.

Mortensen, D. T., & Pissarides, C. A. (1994). Job creation and job destruction in the theory of unemployment. Review of Economic Studies, 61, 397–415.

Mulligan, C., & Sala-i-Martin, X. (1999). Gerontocracy, Retirement, and Social Security, NBER Working Papers No. 7117.

Mulligan, C., Gil, R., & Sala-i-Martin, X. (2010). Social security and democracy. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy, 10(1), 1–44.

Pissarides, C. (1998). The impact of employment tax cuts on unemployment and wages: The role of unemployment benefits and tax structure. European Economic Review, 42(1), 155–183.

Pissarides, C. (2000). Equilibrium unemployment theory. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Saez, E., Matsaganis, M., & Tsakloglou, P. (2012). Earnings determination and taxes: Evidence from a cohort based payroll tax reform in Greece. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(1), 493–533.

Salanié, B. (2003). The economics of taxation. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Summers, L. (1989). Some simple economics of mandated benefits. American Economic Review, 79(2), 177–183.

Tabellini, G., Boeri, T., & Börsch-Supan, A. (2002). Pension reforms and the opinions of European citizens. American Economic Review, 92(2), 396–401.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Juan José Dolado, Miguel-Angel López García, Adam Sanjurjo, the editor Eckhard Janeba and two anonymous referees for their helpful comments and suggestions. Financial support from Instituto Valenciano de Investigaciones Económicas, Generalitat Valenciana (Prometeo/2013/037) and Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (ECO2012-34928) are gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

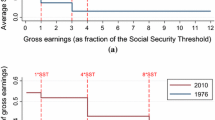

See Fig. 3.

Average rate of social security contributions, in %, OECD countries 2013. Data retrieved from the OECD database, December 2013 (http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx). Data correspond to the average contributions for a two-earner couple, one at 100 % of average earnings and the other at 67 %, with two children

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Iturbe-Ormaetxe, I. Salience of social security contributions and employment. Int Tax Public Finance 22, 741–759 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-014-9322-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-014-9322-3