Abstract

The D1 protein of Photosystem II (PSII), encoded by the psbA genes, is an indispensable component of oxygenic photosynthesis. Due to strongly oxidative chemistry of PSII water splitting, the D1 protein is prone to constant photodamage requiring its replacement, whereas most of the other PSII subunits remain ordinarily undamaged. In cyanobacteria, the D1 protein is encoded by a psbA gene family, whose members are differentially expressed according to environmental cues. Here, the regulation of the psbA gene expression is first discussed with emphasis on the model organisms Synechococcus sp. and Synechocystis sp. Then, a general classification of cyanobacterial D1 isoforms in various cyanobacterial species into D1m, D1:1, D1:2, and D1′ forms depending on their expression pattern under acclimated growth conditions and upon stress is discussed, taking into consideration the phototolerance of different D1 forms and the expression conditions of respective members of the psbA gene family.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cyanobacteria, algae, and higher plants have a unique capacity to use water as a source of electrons in reducing CO2 to various organic compounds. In organisms performing oxygenic photosynthesis, the linear electron transfer (light reactions) takes place in the thylakoid membrane-embedded protein complexes Photosystem II (PSII), Cytochrome b6f (Cytb6f), and Photosystem I (PSI). These multiprotein complexes harness solar energy and, together with ATP synthase, produce reducing power (NADPH) and chemical energy (ATP) for production of carbohydrates. These carbohydrates together with oxygen, the side product of photosynthetic electron transfer, enable all heterotrophic life on Earth.

The core of PSII multisubunit pigment protein complex is composed of the D1 and D2 proteins, which are involved in ligating most of the redox active components of PSII including the Mn4Ca cluster, the site of water oxidation. The primary charge separation in PSII results in highly oxidating chlorophyll (Chl) cation P680+, which is the only biological compound strong enough to drive water oxidation. The recombination of Chl cation P680+ with downstream electron transport cofactors pheophytin (Phe)− or the primary stable electron acceptor plastoquinone Q −A can lead to the formation of triplet Chl states and ultimately to the formation of singlet oxygen, which in turn may damage the photosynthetic machinery. In addition to various protective mechanisms [1, 2], the PSII repair cycle functions to replace the damaged reaction centre protein D1 with a de novo synthesized copy [3, 4] (Fig. 1). The D1 protein is degraded and replaced by a new copy every 5 h under low light growth conditions, and every 20 min under intense illumination [5], to guarantee the maintenance of a steady-state level of the D1 protein in PSII complexes. Due to the capacity of photosynthetic organisms to increase the turn-over rate of the D1 protein upon increasing light intensity, a decrease in the total amount of D1 protein occurs only upon prolonged and severe light stress, which results in impairment of the photosynthetic capacity, i.e., photoinhibition [3, 4]. Hence, the expression of the psbA gene(s) encoding the D1 protein must be under strict control to guarantee the function of the photosynthetic machinery under ever-changing environmental conditions.

Simplified scheme of the PSII repair cycle. Functional PSII dimers are inactivated by light, and the D1 protein is damaged. After partial disassembly of PSII, the damaged D1 protein is accessed by the FtsH protease, and degraded. Subsequently, the ribosome-nascent D1 chain complex is targeted to the thylakoid membrane, and the D1 protein is co-translationally inserted into the membrane and the PSII complex. The C-terminus of the D1 protein is post-translationally processed, PSII is re-assembled, activated, and the PSII dimers are formed

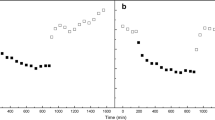

In higher plants, the psbA gene encoding the PSII reaction centre protein D1 is present only in one copy, while all cyanobacteria have a small psbA gene family ranging from one to six members (Table 1; http://www.kazusa.or.jp/cyano/, http://genome.jgi-psf.org/). In the chloroplast genome of some conifers, however, the psbA gene has been duplicated [6]. Despite the difference in gene number, the similarity of the plant and cyanobacterial strategies in psbA gene expression is amazing, and is exemplified by the studies showing the suitability of higher plant psbA gene promoter to control the expression of the psbA gene in cyanobacteria [7, 8]. Still, the presence of multiple psbA genes encoding different D1 isoforms in cyanobacteria is an indication of their importance in regulatory mechanisms responsible for maintaining a functional PSII upon changing environmental conditions in natural habitats of cyanobacteria. Regulation of the psbA gene family members in cyanobacteria follows at least two distinct mechanistic principles. One strategy is to replace the D1 protein present in PSII centres under unstressed conditions with a different form when the stress is detected (Fig. 2a). The other strategy is, upon stress conditions, to increase the turn-over of the same D1 protein produced under basic growth conditions (Fig. 2b). Both of these strategies have been demonstrated in more than one cyanobacterial species. Yet a new regulation mechanism was recently documented in several cyanobacterial species concerning the divergent and “silent” psbA genes, which were proven to be induced by microaerobic/low oxygen conditions [9, 10].

Mode of expression of the psbA genes. a Regulation of the psbA genes in Synechococcus 7942, which contains the D1:1 and D1:2 forms. Upon standard conditions, the psbAI gene is actively transcribed while the psbAII and psbAIII genes are repressed, and accordingly the D1:1 isoform is synthesized and accumulates in PSII complexes. High light (or other stresses resulting in thiol-reducing conditions) activates the transcription of the psbAII and psbAIII genes with concomitant inactivation of psbAI. Consequently, the D1:2 isoform accumulates in PSII complexes. Adaptation to the new ambient conditions reverses the situation. b Regulation of the psbA2 and psbA3 genes in Synechocystis 6803, which contains the D1m and D1′ forms. Under standard conditions, the psbA1 gene is silent and most of the psbA transcripts and the D1m protein are produced by the psbA2 gene. Intense illumination results in enhanced transcription rate of the psbA2 and especially that of psbA3, providing transcripts for rapid D1 turnover. Transcription of trace amounts of psbA1 gene also occurs at high light intensity, but no D1′ protein has been found to accumulate in PSII complexes. c Regulation of the “silent” psbA1 gene, which is induced under low O2 pressure and encodes the D1′ form. Transcript or protein products of the psbA1 gene in Synechocystis 6803, previously thought to be a silent gene, cannot be detected under standard growth conditions. Microaerobic or anaerobic conditions result in activation of transcription

A vast number of studies focusing on regulation of cyanobacterial psbA gene expression have been published during the past two decades. Although more and more details are currently being disclosed, the ultimate mechanisms concerning especially the trans-acting factors regulating the psbA gene expression still remain to be revealed. It has also become clear that, although the increase in psbA transcripts is a general response of cyanobacteria upon shift of the cells to high light intensity, each strain seems to have its own characteristic regulation mechanisms which cannot be directly generalized to other strains. Here, we have summarized the current knowledge about regulation of psbA gene expression with major focus on studies performed with model organisms Synechococcus elongatus sp. PCC 7942 (hereafter, Synechococcus 7942) and Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 and 6714 (hereafter, Synechocystis 6803 and 6714, respectively). Although at least in some species also valid to the psbA genes, we have here excluded the circadian regulation of gene expression, which was recently reviewed in [11]. We apologize for not being able to present results from all published experimental systems due to space limitation and for the sake of clarity.

Regulation of psbA gene expression in cyanobacteria

As typical to eubacteria, the psbA gene expression can be expected to be regulated at the levels of transcription initiation, elongation, and termination, mRNA stability as well as translation. In cyanobacteria, the initiation of transcription is considered to be the most crucial determinant of gene expression. RNA polymerase holoenzyme, composed of the catalytically active core and one of the several sigma factors, initiates transcription. The sigma factors are responsible for promoter recognition, and the chromatine structure along with various cis-acting elements up- and downstream from the transcription start site regulates the level of gene expression. It has been shown that the principal sigma factor (Group 1) specifically recognizes the hexameric −35 and −10 regions located in the promoter region of many cyanobacterial psbA genes [12–14]. The light-responsive expression of the psbA gene, however, seems to require the function of SigB, SigD, and SigE [15–18].

The tertiary structure of DNA is known to have a marked effect on gene expression [19]. AT repeats on one face of the DNA, often found in the region −240 to −40 from the transcriptional start, influence the formation of DNA double helix, and these bends may modulate transcriptional activity. An intrinsic curvature composed of several AT tracts has been found in the upstream region of psbA genes in many organisms including Synechocystis 6803 and Microcystis aeruginosa K-81 [20, 21]. Modification of these tracts was observed to severely downregulate the transcription of the psbA gene, which, however, still remained light-responsive in nature.

Specific features of psbA gene regulation have mainly been addressed in studies with Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 and Synechocystis 6803 and 6714. Below, we focus on regulation of psbA gene expression in these species.

psbA gene expression in Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942

In Synechococcus 7942, the three psbA genes encode two distinct D1 protein isoforms, D1:1 being encoded by psbAI and D1:2 by psbAII and psbAIII [22–27]. Under low light conditions (125 μmol photons m−2 s−1), more than 80% of total psbA transcripts originate from psbAI, but a shift of Synechococcus 7942 cells to high light (750 μmol photons m−2 s−1) decreases the transcription of psbAI while the transcription of psbAII and psbAIII increases [28–31]. Due to enhanced turnover and differences in transcription activity between the psbAI and the psbAII and psbAIII genes, a rapid interchange of the D1:1 form by D1:2 occurs upon shift of cells to high light, which in turn is important for adaptation of cells to changing environmental cues [23, 24, 27, 32–34]. Moreover, mutant strains of Synechococcus 7942 [22] in which the exchange of D1:1 to D1:2 is blocked suffer enhanced inhibition of PSII under UVB and high light illumination [35], showing that the two isoforms are functionally distinct.

All three psbA genes in Synechococcus 7942 give rise to transcripts of 1.2 kb with 5′ ends comprising 49–52 bases upstream from the coding region (Fig. 3a; [22]). The constitutive expression of the psbAII and psbAIII genes is driven by basal σ70 type promoter elements residing between −39 and +12 for psbAII and positions −38 and −1 for psbAIII [30], whereas in psbAI the σ70 promoter TATAAT is replaced by an atypical −10 element, TCTCCT [22]. In addition to the promoter of the psbA gene, there are regulatory elements within the transcribed region, which enhance gene expression and confer light-responsiveness.

Regulatory elements of the psbA genes. a Regulatory elements of the psbAI, psbAII and psbAIII genes in Synechococcus 7942 (not in scale). The region composing the 1.2 kb transcript of each psbA gene is shown as a thick line. The coding region (starting with ATG) is marked as a solid black line and the 5′UTR as a striped line with a number below indicating the length in base pairs (bp). For each gene, the −10 and −30 regulatory elements (atypical TCTCCT in psbAI) are shown. The black triangles show the approximate binding sites for various (putative) trans-acting regulatory factors. (1) One psbAI-specific and at least one regulatory factor shared with psbAI and psbAII bind to the 5′ end of the psbAI coding region. (2) The degradation products of the D1:1 protein bind to the upstream region of the psbAI gene. (3–4) CmpR increases the expression of psbAII and psbAIII by interacting with the TTA-N7/8-TAA sequence. Other uncharacterized regulatory proteins may be involved as well, and the AT-rich region downstream from the basal elements of the psbAII gene may additionally affect the gene expression. Additional negative and positive elements upstream of the basal promoter have been identified (not shown), but the interacting trans-factors remain to be elucidated. b Regulatory elements of the psbA1, psbA2 and psbA3 genes in Synechocystis 6803 (not in scale). The region composing the 1.2 kb transcript of each psbA gene is shown as a thick line. The coding region (starting with ATG) is marked as a solid black line, and the 5′UTR as a striped line with a number below indicating the length in base pairs (bp). The transcription start site of the psbA1 gene is not known. For each gene, the −10 and −30 regulatory elements are shown. The −30 site in psbA1 differs significantly from those of psbA2 and psbA3. The black triangles show the binding sites (TTCAA-N4-TTACAA) of at least one putative transcriptional repressor, which stalls transcription of the psbA2 and psbA3 genes in the dark

psbAI promoter region encompasses nucleotides −54 to +1, and one or more proteins bind specifically to the psbAI upstream region (+1 to +43; [36, 37]). At least one of the regulatory factors is shared with psbAI and psbAII [37], whereas the gel mobility shift experiments have shown binding of a de novo synthesized protein factor specifically to the 5′ end (66 bp) of the psbAI coding region [38]. This so far uncharacterized protein factor is essential for transcriptional activation of the psbAI gene [38]. Moreover, PsfR protein has been identified as a regulator of psbAI gene expression [39]. Overexpression of psfR results in enhanced expression of psbAI without an effect on psbAII and III. However, knock-out of psfR did not prevent psbAI expression. Thomas and coauthors [39] have suggested that PsfR may rather regulate gene expression via protein–protein interactions than via direct binding to the psbAI promoter. Moreover, a recent study suggested that the D1 protein might regulate its own synthesis: gel mobility shift experiments provided evidence that the degradation products of the D1:1 protein bind to the upstream region (−106 to −10) of the psbAI gene, thereby possibly regulating the efficiency of transcription [40]. Additional upstream sequences enhance expression but are not needed for light-responsive regulation.

Both psbAII and psbAIII also bind regulatory proteins in the regions +1 to +41 in psbAII and −2 to +38 in psbAIII. One such protein is CmpR, which is required for expression of the best-characterized low-CO2 inducible operon cmpABCD [41]. The exact binding site of the CmpR protein has been shown to be the palindromic TTA-N7-TAA and TTA-N8-TAA sequences in the enhancer elements of psbAII and psbAIII, respectively [41]. Knock-out of CmpR, however, did not completely stall the expression of the psbA genes. Moreover, the region between the −10 basal promoter and the Shine–Dalgarno sequence of the psbAII gene in Synechococcus 7942 shares similarity with that in Microcystis aeruginosa K-81 [42]. This AT-rich region upstream from the Shine–Dalgarno sequence seems to function as a negative cis-element, which might bind regulatory factors and/or ribosomes affecting accumulation of the psbAII transcripts [42]. Additionally, upstream of the basal promoters are negative elements that depress the expression [30].

Besides the 1.2-kb psbAII transcripts, the psbAII gene also produces 1.6-kb transcripts which originate 419 bp upstream from the start site for the 1.2-kb psbAII mRNA. This dicistronic message contains a 342-bp ORF immediately upstream of the psbAII coding region [28]. Expression of the 1.6-kb transcript, however, is not light dependent [43]. Whether the gene product of this ORF is somehow involved in the regulation of psbA gene expression, for example as a regulatory factor, remains to be elucidated.

Induction of psbAII/III messages occurs not only at high light intensity, but also upon a shift of the cells to low temperature under constant low light intensity, to UVB irradiation as well as to anoxia and to light favoring excitation of PSI [35, 38, 44–46]. However, neither heat shock nor oxidative stress produced similar responses as generated by an increase in light intensity [32]. It is conceivable that the reducing power, produced by the two photosystems, cannot be used efficiently in carbon assimilation under stress conditions, thus leading to elevated levels of thiol reductants. Reducing conditions, in turn, are likely to be sensed as a signal to induce the expression of psbAII/III. Indeed, addition of reduced DTT to the cell suspension was shown to induce the psbAII/III gene expression and down-regulation of the psbAI gene expression. Inhibitors of photosynthetic electron transfer chain (DCMU and DBMIB) did not cause any changes in psbA gene expression when added under low light conditions, but both chemicals dramatically reduced the induction of psbAII/III when added upon a high light shift. These results indicate that the thiol redox state rather than the redox state of the plastoquinone pool regulates psbA gene expression in Synechococcus 7942 [46].

Besides redox regulation, the expression of the psbA genes has been suggested to be controlled via a blue light photoreceptor. Shift of cells to low-fluence blue light was shown to induce transcription of the psbAII/III genes, and this induction could be reversed by a subsequent pulse of red light [47]. Since blue light has been shown to regulate chloroplast gene expression in higher plants, it is possible that components of an ancient blue light photosensory pathway are evolutionarily conserved during the divergence of plant chloroplasts from cyanobacteria [48, 49]. One possible candidate for a blue light receptor is NblS, a putative histidine kinase, which is involved—among other things—in controlling psbA gene expression [50].

Concomitantly with upregulation of psbAII and psbAIII the amount of psbAI transcripts decreases as an immediate reaction when Synechococcus cells are shifted to bright light [29, 51]. This is mostly due to destabilization of the psbAI transcript (T1/2 = 10–12 min), which is dependent on the 52-nt untranslated leader sequence [29, 51]. Destabilization of the psbAI transcript is accompanied by a decrease in transcription activity of the psbAI gene [37]. Similarly, the degradation of the psbAIII mRNA has been shown to be accelerated at high light intensity, but the psbAII transcripts are long-lived and apparently not subject to post-transcriptional regulation [29]. Determinants of psbA mRNA turnover have been shown to reside within the untranslated leader regions of the psbA genes as well as within the coding region [51]. The region encoding the first membrane span of the D1 protein is essential for the stability of both the psbAI and psbAII transcripts, probably via pausing of ribosomes, which protects the mRNAs [51].

In contrast to an immediate response of cells to high light, prolonged exposure of Synechococcus 7942 cells to high light leads to an increased accumulation of all psbA transcripts, including psbAI. This was shown to result from restabilization of the psbAI transcript after several hours at high light intensity [32]. Nevertheless, despite vigorous reaccumulation of psbAI, no corresponding increase in the amount of D1:1 could be detected in the thylakoid membrane of high light-adapted Synechococcus 7942 cells [32] probably due to a high sensitivity of D1:1-containing PSII centres to photoinhibition.

psbA gene expression in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 and 6714

In Synechocystis sp., only one type of D1 (D1m, see below) protein, encoded by both the psbA2 and psbA3 genes, has been detected under normal growth conditions as well as under most stress conditions [52]. However, recent studies have revealed anaerobiosis-induced expression of the psbA1 gene [9, 10], which was previously thought to be a silent pseudogene. The transcript from psbA2 accounts for 90% and from psbA3 for 3–10% of the total psbA transcript pool under normal growth conditions (ca. 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1), whereas under these conditions the psbA1 gene remains silent [52–55]. Intense illumination increases the transcription of the psbA2 and psbA3 genes, and this induction is not affected by addition of electron transfer inhibitors [56–61]. Studies using S1 nuclease protection assay, micro-arrays [62] and northern blotting [63] have shown that UVB exposure of the cells also induces an increase in the total psbA transcript pool primarily through increased accumulation of psbA3 transcripts [57, 64]. However, inactivation of either psbA2 or psbA3 up-regulates the expression of the intact gene to the normal wild type level without marked effects on cell metabolism, indicating that either gene alone is sufficient to support autotrophic growth of the cells [54, 63]. Thus, Synechocystis pattern of supplemental expression of an identical protein isoform under excitation stress is distinct from the D1 isoform exchange found in Synechococcus 7942.

In Synechocystis 6803, both the −35 and −10 elements are present in the upstream regions of the psbA2 and psbA3 genes (Fig. 3b). The transcription start points for psbA2 and psbA3 have been mapped to positions −49 and −88, respectively, relative to the ATG site [52]. The promoter region of psbA1 differs significantly from those of psbA2 and psbA3, especially in the −35 element, which is identical in psbA2 and psbA3. psbA1 also lacks a Shine–Dalgarno sequence, which, however, is not absolutely required for successful translation [65]. The transcription start site of psbA1 has not yet been defined and hence the location of promoter is uncertain. In addition to the possible promoter next to the coding region of the psbA1 gene, there is a distal promoter-like region.

Synechocystis 6803 mutants with modified degradation rates of the D1 protein have provided evidence that not only light intensity but also the rate of D1 synthesis regulates transcription of the psbA2 and psbA3 genes [5, 66–69], which additionally seems to require de novo synthesized protein factors [70, 71]. Transcription of the psbA genes during the recovery process after photoinhibitory treatment of Synechocystis 6714, however, was not prevented by inhibition of translation, and the photoinhibitory treatment longer than 40 min finally resulted in increased stability of the psbA messages [58]. Transcription of the psbA genes ceases rapidly upon shift of the cells to darkness, even in the presence of an external energy source, indicating that the energy status of the cells does not directly affect the transcription activity of the psbA genes in Synechocystis [60].

Numerous studies during the past 10 years have suggested an involvement of the intersystem redox status in the regulation of psbA gene expression in Synechocystis 6803. These experiments mainly followed the accumulation of psbA transcripts in cells exposed to different nutrient regimes, light quantities and qualities as well as to electron transfer inhibitors, DCMU and DBMIB. The presence of DCMU or DBMIB upon illumination of cells results in accumulation of PSII reaction centres with a reduced quinone at a QA site, which was suggested to act as a signal to transiently increase the amount of psbA transcripts in Synechocystis 6803 and 6714 [59]. A more recent study by the same authors suggested that the occupancy of the plastoquinone binding QO site in the Cyt b6f complex might be involved in regulation of the psbA gene expression. This conclusion was deduced from the fact that the reduction of the intersystem carriers activated the transcription of the psbA gene and destabilized the message, whereas oxidation of the electron transfer chain decreased transcription and stabilized the psbA message [72]. Li and Sherman have shown that long-term (6 h) treatment of Synechocystis 6803 cells with either DCMU or DBMIB has strong effects on accumulation of psbA transcripts and indicated that reduction of the plastoquinone pool (presence of DBMIB) decreases, and oxidation (presence of DCMU) increases the expression of the psbA genes [69]. RppA, a response regulator of a two-component system, was suggested to sense the changes in the redox poise and accordingly to adjust the stoichiometry between PSII and PSI via regulating the expression of photosynthetic genes, e.g., psbA [69]. The effects of blue, orange, and far-red light on the expression of psbA gene in Synechocystis 6803 made El Bissati and coworkers conclude that light quality regulates the expression of photosynthetic genes via a redox control occurring in the Cyt b6f complex [73]. However, data not supporting this interpretation also exist. Comparison of the action spectra of psbA transcription to that of PSII activity, photosynthesis and photoinhibition [63], as well as subjecting Synechocystis 6803 cells to over-saturating single turn-over flashes inducing photoinhibition but without affecting the oxidation state of the intersystem redox carriers [61], made the authors conclude that the redox state of the electron transfer chain is an unlikely candidate to carry information for regulation of psbA expression.

The half-life of psbA2 and psbA3 transcripts in Synechocystis 6803 under illumination is around 10–20 min, and independent of light intensity or the rate of PSII electron transfer [56, 58, 59, 66, 72, 74], whereas the stability of psbA transcripts increases remarkably in darkness [56, 60, 71, 75]. Stabilization of transcripts is dependent on cessation of photosynthetic electron transfer rather than on light per se [56, 60, 61, 72]. Other factors, such as polyamines, have also been suggested to affect the stability of psbA transcripts [71]. Transfer of dark-treated cells back to light induces rapid protein-synthesis-independent accumulation of psbA transcripts [60]. Indeed, the 170-bp upstream region of the psbA2 gene was shown to bind protein factors in the dark, suggesting that the transcription of the psbA2 gene is down-regulated in darkness via transcriptional repressor proteins [60]. Specifically, a hexanucleotide direct repeat, TTACAA-N4-TTACAA, found in the promoter region of Synechocystis 6803 psbA2 and psbA3 genes as well as in Anabaena 7120, has been shown to act as a binding site for a putative repressor in the dark (Fig. 3b; [76]).

Translational regulation of D1 synthesis in cyanobacteria

It is well known that translation is a key regulatory step in the chloroplasts of higher plants, and many trans-acting factors involved in translation of the D1 protein in chloroplasts have been characterized since the 1980s [77]. Evidence is accumulating indicating that the D1 protein synthesis in cyanobacteria is also not solely controlled at the transcriptional level, e.g., in Synechococcus 7942, practically no D1:1 protein accumulated upon stress in the thylakoid membrane, even though high amounts of psbAI transcripts were present [32, 35, 46, 78]. Moreover, upon anoxia and under thiol-reducing conditions in the presence of electron transfer inhibitors, a substantial amount of psbAII/III messages accumulates without synthesis of the D1:2 protein [45, 79]. It has been shown that, if there are psbA transcripts present in Synechococcus 7942, the messages are always efficiently associated with ribosomes, suggesting that initiation of translation does not play a significant role in regulation of psbA gene expression, whereas membrane targeting of nascent D1 protein ribosome complex might, at least under some conditions, be a rate-limiting step for D1 protein synthesis [5]. Elongation of translation is also under strict regulation in Synechocystis 6803: upon shift of the cells from light to darkness, the abundant psbA transcripts keep attached to ribosomes and D1 translation continues up to a distinct pausing site. However, the newly formed ribosome-nascent D1 chain complexes are not targeted to the thylakoid membrane, and therefore no complete D1 synthesis takes place in the dark [80]. Indeed, the ribosome complexes are targeted to the thylakoid membranes and D1 synthesis can be completed only in light to replace the damaged D1 protein, indicating that it is not the initiation of translation but rather the translational elongation that is an important regulatory step in expression of the psbA genes [80]. Translational elongation of proteins in general and in particular that of the D1 protein is also sensitive to singlet oxygen, which is generated especially during photosynthesis [81, 82]. An additional regulatory factor is the availability of chlorophyll: although the accumulation of psbA transcripts is independent of chlorophyll availability, the lack of chlorophyll seems to affect the initiation of psbA translation [83]. Further complexity to the regulation of psbA gene expression is provided by the membrane insertion and C-terminal processing of the D1 protein as well as the assembly of PSII (see [84] and references therein). The different steps of PSII assembly and function are assisted by a number of auxiliary proteins, including factors involved in degradation of the damaged D1 protein, in translation and membrane insertion of the new D1 copy, and in PSII (super) complex formation and activation [85, 86]. Putative antisense mRNAs against various psbA genes in Synechocystis 6803 might represent a novel regulatory network in psbA gene expression and are presently under intense research (Wolfgang Hess, unpublished results).

Functional classification of cyanobacterial D1 proteins

Nearly 40 fully sequenced cyanobacterial genomes together with functional characterization of several psbA gene families make it now possible to attempt to classify this important gene family and its product, the D1 protein. This, however, faces a serious difficulty since the psbA genes within a species tend to be more closely related to their family relatives than to functionally similar members of other species. Therefore, the classification of D1 isoforms based solely on the genomic data is unavoidably prone to errors. In order to be accurate, one has to take into consideration the specific response and behavior of the individual members of the gene family as a response to a variety of factors. From evidence accumulated so far, we attempt here a classification of the D1 isoforms based on the manner that their expression is regulated under typical growth conditions as well as under various environmental stresses (Fig. 2; Table 1).

From a functional point of view cyanobacterial D1 proteins can be divided into the following four categories:

-

i)

D1m is a D1 form expressed and present in the PSII centres under normal growth conditions. D1m is also induced under most stress conditions (m denotes for “major”);

-

ii)

D1:1 is a D1 form expressed and assembled into PSII under normal growth conditions, but repressed under stress;

-

iii)

D1:2 is a D1 form repressed under normal growth conditions, but induced and accumulated into PSII by stress;

-

iv)

D1′ is a D1 form virtually silent under standard growth conditions, but induced under microaerobic/low oxygen conditions

In the following section, we will characterize the above-mentioned D1 isoforms one by one. The individual functional distinctiveness of each D1 form, and the justification of placing them in these distinct categories, is also discussed.

The D1m isoform

Charasteristic to the D1m isoform is its presence in PSII centres both under normal growth conditions and when the cells are exposed to stress. This isoform thus contributes to the maintenance of functional PSII, but the defining trait is its increased expression under environmental stress conditions that speed up D1 degradation. A typical example of D1m is the D1 isoform encoded by the psbA2 and psbA3 genes in Synechocystis 6803 (see “ psbA gene expression in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 and 6714”). In this cyanobacterium, the psbA2 transcript is responsible for almost all the D1 protein produced under regular growth. When the rate of D1 degradation increases, e.g., upon exposure of the cells to high light or UVB stress, the transcription of the psbA3 gene is considerably enhanced thereby enabling an increased turnover rate of the D1 protein (Fig. 2b). When the stress condition is removed, the pattern of the psbA2 and psbA3 gene expression reverses. Both genes are alone sufficient to support normal autotrophic growth mode of the cells [54, 87].

Interestingly, Gloeobaacter violaceus PCC 7421, a cyanobacterium that shows deep molecular and ultrastructural divergence from other cyanobacteria and is considered very primitive, regulates its five psbA genes in a similar manner as Synechocystis 6803 [88]. Under standard growth conditions (10 μmol photons m−2 s−1, 25°C), the D1 protein is produced by psbAI (glr2322) and psbAII (glr0779) both showing considerably high levels of expression, whereas under stress, psbAIII (gll3144) is induced supplementing the available transcripts. All three genes are encoding the same D1 isoform. The other two psbA genes in Gloeobacter encode distinctly different D1 proteins of unclear function. One of them, psbAV (glr2656), encodes the most divergent psbA sequence known to date [88].

The D1:1 isoform

D1:1, also known as D1 form 1, is best described in Synechococcus 7942 and is, together with D1:2, part of a specific regulation mechanism in response to stress conditions. Recently, a similar stress-response mechanism was revealed in Anabaena PCC 7120, Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP-1, and the marine Synechococcus WH 7803 [89]. These are diverse cyanobacterial species with no easily traceable phylogenetic relationship. The defining characteristic of D1:1 is its high level of expression in well-acclimated cells, and a distinct down-regulation upon abrupt changes in the standard growth conditions (Fig. 2a). Once the cell acclimates to the new status quo or the stress is removed the expression of the genes encoding D1:1 increases and it becomes once again the dominant D1 form in PSII centres. For some time, D1:1 was also associated with the presence of a specific amino acid at position 130 proven to influence the potential of the redox active D1-Phe residue (see discussion in the next section). This is situated in a conserved portion of the D1 protein and it has been proven true, so far, that the D1:1 protein always contains a glutamine residue at this position. While this is true, the reverse is not: not every D1 with a glutamine at 130 is a D1:1. A clear example is the low-expressed, divergent D1′ encoding psbA genes from Anabaena 7120 (psbA0) and Synechocystis 6803 (psbA1) that have a glutamine at position 130 but functionally are clearly not D1:1 forms (see the following section on D1′).

The D1:2 isoform

The D1:2 isoform reflects the mirror image of its “sister” form D1:1 in its expression. D1:2 is expressed at low level in well-acclimated cells, but upon stress conditions the expression is markedly induced and D1:2 replaces D1:1 in PSII centres (Fig. 2a). Upon acclimation or removal of stress, the D1:2 will be repressed and replaced by D1:1. This D1 form exchange is one of the clearest mechanisms documented so far on gene regulation as adaptation to changing environmental conditions, and it was well documented in Synechococcus 7942 by numerous studies (see “ psbA gene expression in Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942”). The exchange is facilitated by the fast turnover rate of the D1 protein, establishing a correlation between the expression levels of distinct psbA genes, the form of D1 protein present in PSII centres, and the functional characteristics of PSII. The evolutionary development and maintenance of this regulation mechanism speaks for a direct requirement of the functional characteristics of both D1 forms, thus offering unique advantages under their specific expression conditions. A good question raised by the presence of D1:2 under stress conditions is why the cells do not always possess D1:2 in the PSII centres? The answer, while not clear yet, has to do with a discreet advantage of D1:1 over D1:2 under standard growth conditions. Maintenance of D1:1 in the PSII centres seems to give an evolutionary advantage over mutants containing only the D1:2 form, generated by random mutagenesis.

D1:2 is a functionally well-defined form and different from its counterpart D1:1, as shown by artificially made mutant strains of Synechococcus 7942 [22]. In these strains, the exchange of D1:1 to D1:2 is blocked, which results in enhanced PSII photoinhibition under UVB and high light illumination [35]. Furthermore, it has been shown that a transgenic Synechocystis 6803 strain expressing the Synechococcus 7942 D1:2 isoform possesses a faster decay of variable fluorescence in the presence of DCMU, reflecting faster recombination of reduced QA with positive charges on the donor side of PSII, compared to a Synechocystis 6803 mutant expressing only the D1:1 isoform from Synechococcus 7942 [25]. Thermoluminescence [27] and fluorescence life time data [26] from Synechococcus 7942 cells containing only the D1:1 or the D1:2 isoform also support enhanced charge recombination in PSII centers containing D1:2. It is important to note that this functional difference between the D1:1 and D1:2 isoforms is correlated with the presence of a glutamate residue in D1:2 instead of a glutamine residue at position 130 in the D1 protein sequence, which interacts with a key Phe co-factor [7, 90]. It was recently shown that Glu occupies D1-130 position in all high-light D1 isoforms identified so far, whereas Gln is found in the low light D1 isoforms, like D1:1 [91]. The correlation of the D1 Gln130Glu amino acid replacement with phototolerance is apparently related to accelerated charge recombination, i.e., to the existence of an Em (Phe/Phe−)-dependent photoprotection [92]. It is worth noting here that the single D1 protein in higher plants has strictly conserved Glu130 residue.

The D1′ isoform

The term D1′ was for a long time used only for the product of psbA1 gene in Synechocystis 6803. This gene was considered enigmatic as its open reading frame was intact but its transcript could not be detected by classic hybridization methods [54, 56, 75]. However, artificial activation of psbA1 in Synechocystis 6803 [53], via replacement of the 320-bp upstream fragment of the psbA1 gene with a 160-bp upstream fragment of psbA2, leads to production of a functional and light-responsive, albeit aberrant, D1 protein [93, 94]. Whole genome sequences and functional studies recently published from several cyanobacterial species (http://www.kazusa.or.jp/cyano/, http://genome.jgi-psf.org/) have revealed that, apart from Synechocystis 6803, a psbA1-type divergent, low-expressed and non-responsive psbA gene also exist in Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 (psbA0-alr3742) [95], Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP-1 (psbA2-tlr1844) [91, 96], Cyanothece sp. ATCC 51142 (psbA2) [10], and possibly Gloeobacter violaceus PCC 7421 [88]. So far, in cyanobacterial species where the expression of the psbA gene family has been characterized, Synechococcus 7942 is the only species that does not contain such a gene [32].

During the past year, two independent studies demonstrated induction of the psbA gene encoding the D1′ isoform under microaerobic [9] or low oxygen [10] conditions in Synechocystis 6803, Anabaena 7120, Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP-1, and Cyanothece sp. ATCC 51142 (Fig. 2c). Already earlier, the Anabaena psbA0 (alr3742) gene was found to be expressed at a very low constitutive level and was not responsive to photo-oxidative UVB stress, light stress, or nitrogen stress [95]. This behavior of psbA0 of Anabaena 7120 is very similar to that of psbA1 of Synechocystis 6803. Indeed, both these genes are in fact not silent even under normal growth conditions, but transcribed to a very low level insufficient to play a significant role as part of the cellular psbA transcript pool [95].

While still we do not have an answer regarding the direct functional role of the D1′ isoform, we can now with a high degree of confidence establish D1′ as a widely distributed D1 isoform important for adaptation of cyanobacterial cells to specific environmental conditions, particularly to a microaerobic pressure. The conditions requiring the presence of D1′ thus have a sufficient evolutionary importance to ensure that the gene has been selectively maintained in the genome. There are no major sequence characteristics that would individualize the D1′ from the other D1 forms. In the D1 forms functionally characterized [9], there are only three amino acid residues that are both conserved in all traditional D1 forms and mutated but conserved across all the D1′ proteins. These modifications are Gly80Ala, Phe158Leu, and Thr286Ala [9]. The low-oxygen-pressure-induced D1′ form encoded by psbA2 in Cyanothece [10] also has the same consistent modifications. Some initial molecular modelling studies did not show any major D1 conformational changes [9], and it is not yet clear what, if any, are the implications of these modifications on the general PSII function. It is worth mentioning, however, that at least two of the conserved modifications in D1′ (Phe158Leu and Thr286Ala) are located in the binding pockets of important Chl residues: ChlD1, the place of initial charge separation, and Chl PD1, the most probable location of the stable cation P680+. The fact that the genes encoding D1′ are present in such a diverse array of cyanobacterial species and that all these genes apparently respond to the same environmental cue makes it very likely that the encoded D1 protein belongs to a distinct category: D1′. The clear selective advantage of D1′ over the regular D1 is not obvious and remains to be identified. Also, while under standard laboratory growth conditions the cells do not usually experience periods of microaerobic growth, in the natural environment they do occur as a result from imbalanced cellular metabolism, specific environmental conditions or due to niche a given cyanobacteria inhabits, e.g., in microbial mats [97].

psbA genes in cyanophages

Cyanobacteria are responsible for a majority of primary production in oligotrophic regions of oceans. Cyanophages, viruses that infect cyanobacteria, are equally abundant in marine ecosystems, and probably exert major ecological effects on the marine environment [98, 99]. The first cyanophages were isolated in 1963 [100], but only recently it has been found that many of the cyanophages infecting Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus hosts possess psbA and psbD genes encoding the D1 and D2 proteins, respectively [101–107]. The photosynthesis genes in cyanophages originate from their host cyanobacteria, and thus show marked (up to 95%) identity to their host homologs at amino acid level [103, 105, 108, 109]. Accordingly, Prochlorococcus myoviruses and podoviruses encode the only D1 form found in Prochlorococcus, whereas in Synechococcus myoviruses, the stress-responsive D1:2 form of Synechococcus D1 protein has been selected over D1:1 [107].

It has been shown that the cyanophage psbA gene is indeed both transcribed and translated in cyanobacteria during infection [104, 110], and at the same time the expression of the host photosynthesis genes declines [104]. Since all bacteriophages rely on their hosts to provide energy and carbon sources for replication and assembly, it is conceivable that the expression of the cyanophage psbA gene allows continuous operation of the PSII repair cycle (Fig. 1), even if infection down-regulates the expression of the host psbA gene. Thus, the D1 protein encoded by the cyanophage is likely to replace the light-sensitive D1 protein of the host (despite possessing some unique features in structure [111]), thus allowing photosynthesis to continue efficiently even under bright light [104, 110, 112, 113], and thereby provide the energy needed by the virus for its replication. Obviously, the prevalence of photosynthesis genes in cyanophages serves as a valuable genetic reservoir for the host, and has probably played a role in driving host niche differentiation [105].

Summary

The D1 protein of PSII is a specialized protein component targeted to photodamage and rapid turnover in all organisms performing oxygenic photosynthesis. In cyanobacteria, which can inhabit various extreme habitats, the D1 protein is encoded by a small gene family. Obviously, the range of environmental factors cyanobacteria may face during their life cycle requires the possibility to modify the expression of the psbA genes, and more importantly the presence of a proper D1 isoform in PSII centres, in order to guarantee the best adaptation and fitness under given conditions. Optimal adaptation to varying environmental conditions seems to be obtained via complex regulation of not only one, but several, psbA genes. During the past two decades, it has become clear that there is not a single, universal pattern of regulation of psbA gene expression in cyanobacteria, but rather the ecological niche occupied by the individual strain has guided the evolution towards proper adaptation and satisfactory fitness. Ongoing release of genomic data from a vast number of cyanobacterial species will certainly provide additional tools to further study the regulatory factors of psbA gene expression in different cyanobacterial species. Understanding the adaptation processes of the photosynthetic machinery to changing environmental cues will be of utmost importance when biotechnological applications, for example the production of biofuels and improvement of crop yields, are to be developed.

References

Niyogi KK (1999) Photoprotection revisited: genetic and molecular approaches. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 50:333–359

Munekage Y, Hojo M, Meurer J, Endo T, Tasaka M, Shikanai T (2002) PGR5 is involved in cyclic electron flow around photosystem I and is essential for photoprotection in Arabidopsis. Cell 110:361–371

Aro EM, Virgin I, Andersson B (1993) Photoinhibition of Photosystem II. Inactivation, protein damage and turnover. Biochim Biophys Acta 1143:113–134

Takahashi S, Murata N (2008) How do environmental stresses accelerate photoinhibition? Trends Plant Sci 13:178–182

Tyystjärvi T, Aro EM, Jansson C, Mäenpää P (1994) Changes of amino acid sequence in PEST-like area and QEEET motif affect degradation rate of D1 polypeptide in photosystem II. Plant Mol Biol 25:517–526

Lidholm J, Gustafsson P (1991) The chloroplast genome of the gymnosperm Pinus contorta: a physical map and a complete collection of overlapping clones. Curr Genet 20:161–166

Nixon PJ, Rogner M, Diner BA (1991) Expression of a higher plant psbA gene in Synechocystis 6803 yields a functional hybrid photosystem II reaction center complex. Plant Cell 3:383–395

Dzelzkalns VA, Owens GC, Bogorad L (1984) Chloroplast promoter driven expression of the chloramphenicol acetyl transferase gene in a cyanobacterium. Nucleic Acids Res 12:8917–8925

Sicora CI, Ho FM, Salminen T, Styring S, Aro EM (2009) Transcription of a “silent” cyanobacterial psbA gene is induced by microaerobic conditions. Biochim Biophys Acta 1787:105–112

Summerfield TC, Toepel J, Sherman LA (2008) Low-oxygen induction of normally cryptic psbA genes in cyanobacteria. Biochemistry 47:12939–12941

Williams SB (2007) A circadian timing mechanism in the cyanobacteria. Adv Microb Physiol 52:229–296

Shibato J, Asayama M, Shirai M (1998) Specific recognition of the cyanobacterial psbA promoter by RNA polymerases containing principal sigma factors. Biochim Biophys Acta 1442:296–303

Schneider GJ, Tumer NE, Richaud C, Borbely G, Haselkorn R (1987) Purification and characterization of RNA polymerase from the cyanobacterium Anabaena 7120. J Biol Chem 262:14633–14639

Schneider GJ, Lang JD, Haselkorn R (1991) Promoter recognition by the RNA polymerase from vegetative cells of the cyanobacterium Anabaena 7120. Gene 105:51–60

Yoshimura T, Imamura S, Tanaka K, Shirai M, Asayama M (2007) Cooperation of group 2 sigma factors, SigD and SigE for light-induced transcription in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. FEBS Lett 581:1495–1500

Imamura S, Asayama M, Shirai M (2004) In vitro transcription analysis by reconstituted cyanobacterial RNA polymerase: roles of group 1 and 2 sigma factors and a core subunit, RpoC2. Genes Cells 9:1175–1187

Imamura S, Yoshihara S, Nakano S, Shiozaki N, Yamada A, Tanaka K, Takahashi H, Asayama M, Shirai M (2003) Purification, characterization, and gene expression of all sigma factors of RNA polymerase in a cyanobacterium. J Mol Biol 325:857–872

Pollari M, Ruotsalainen V, Rantamäki S, Tyystjärvi E, Tyystjärvi T (2009) Simultaneous inactivation of sigma factors B, D interferes with light acclimation of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J Bacteriol 191:3992–4001

Willenbrock H, Ussery DW (2004) Chromatin architecture and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Genome Biol 5:252

Agrawal GK, Asayama M, Shirai M (1997) A novel bend of DNA CIT: changeable bending-center sites of an intrinsic curvature under temperature conditions. FEMS Microbiol Lett 147:139–145

Asayama M, Kato H, Shibato J, Shirai M, Ohyama T (2002) The curved DNA structure in the 5’-upstream region of the light-responsive genes: its universality, binding factor and function for cyanobacterial psbA transcription. Nucleic Acids Res 30:4658–4666

Golden SS, Brusslan J, Haselkorn R (1986) Expression of a family of psbA genes encoding a photosystem II polypeptide in the cyanobacterium Anacystis nidulans R2. EMBO J 5:2789–2798

Clarke AK, Hurry VM, Gustafsson P, Öquist G (1993) Two functionally distinct forms of the photosystem II reaction-center protein D1 in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:11985–11989

Clarke AK, Soitamo A, Gustafsson P, Öquist G (1993) Rapid interchange between two distinct forms of cyanobacterial photosystem II reaction-center protein D1 in response to photoinhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:9973–9977

Tichy M, Lupinkova L, Sicora C, Vass I, Kuvikova S, Prasil O, Komenda J (2003) Synechocystis 6803 mutants expressing distinct forms of the Photosystem II D1 protein from Synechococcus 7942: relationship between the psbA coding region and sensitivity to visible and UV-B radiation. Biochim Biophys Acta 1605:55–66

Campbell D, Bruce D, Carpenter C, Gustafsson P, Öquist G (1996) Two forms of the photosystem II D1 protein alter energy dissipation and state transitions in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942. Photosynth Res 47:131–144

Sane PV, Ivanov AG, Sveshnikov D, Huner NP, Öquist G (2002) A transient exchange of the photosystem II reaction center protein D1:1 with D1:2 during low temperature stress of Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942 in the light lowers the redox potential of QB. J Biol Chem 277:32739–32745

Schaefer MR, Golden SS (1989) Differential expression of members of a cyanobacterial psbA gene family in response to light. J Bacteriol 171:3973–3981

Kulkarni RD, Schaefer MR, Golden SS (1992) Transcriptional and posttranscriptional components of psbA response to high light intensity in Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942. J Bacteriol 174:3775–3781

Li R, Golden SS (1993) Enhancer activity of light-responsive regulatory elements in the untranslated leader regions of cyanobacterial psbA genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:11678–11682

Bustos SA, Golden SS (1991) Expression of the psbDII gene in Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942 requires sequences downstream of the transcription start site. J Bacteriol 173:7525–7533

Kulkarni RD, Golden SS (1994) Adaptation to high light intensity in Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942: regulation of three psbA genes and two forms of the D1 protein. J Bacteriol 176:959–965

Krupa Z, Öquist G, Gustafsson P (1990) Photoinhibition and recovery of photosynthesis in psbA gene-inactivated strains of cyanobacterium Anacystis nidulans. Plant Physiol 93:1–6

Soitamo AJ, Zhou G, Clarke AK, Öquist G, Gustafsson P, Aro EM (1996) Over-production of the D1:2 protein makes Synechococcus cells more tolerant to photoinhibition of photosystem II. Plant Mol Biol 30:467–478

Campbell D, Eriksson MJ, Öquist G, Gustafsson P, Clarke AK (1998) The cyanobacterium Synechococcus resists UV-B by exchanging photosystem II reaction-center D1 proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:364–369

Li R, Dickerson NS, Mueller UW, Golden SS (1995) Specific binding of Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942 proteins to the enhancer element of psbAII required for high-light-induced expression. J Bacteriol 177:508–516

Nair U, Thomas C, Golden SS (2001) Functional elements of the strong psbAI promoter of Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. J Bacteriol 183:1740–1747

Soitamo AJ, Sippola K, Aro EM (1998) Expression of psbA genes produces prominent 5’ psbA mRNA fragments in Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942. Plant Mol Biol 37:1023–1033

Thomas C, Andersson CR, Canales SR, Golden SS (2004) PsfR, a factor that stimulates psbAI expression in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. Microbiology 150:1031–1040

Stelljes C, Koenig F (2007) Specific binding of D1 protein degradation products to the psbAI promoter in Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942. J Bacteriol 189:1722–1726

Takahashi Y, Yamaguchi O, Omata T (2004) Roles of CmpR, a LysR family transcriptional regulator, in acclimation of the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942 to low-CO(2) and high-light conditions. Mol Microbiol 52:837–845

Agrawal GK, Kato H, Asayama M, Shirai M (2001) An AU-box motif upstream of the SD sequence of light-dependent psbA transcripts confers mRNA instability in darkness in cyanobacteria. Nucleic Acids Res 29:1835–1843

Bustos SA, Schaefer MR, Golden SS (1990) Different and rapid responses of four cyanobacterial psbA transcripts to changes in light intensity. J Bacteriol 172:1998–2004

Campbell D, Zhou G, Gustafsson P, Öquist G, Clarke AK (1995) Electron transport regulates exchange of two forms of photosystem II D1 protein in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus. EMBO J 14:5457–5466

Campbell T, Clarke AK, Gustafsson P, Öquist G (1999) Oxygen-dependent electron flow influences photosystem II function and psbA gene expression in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942. Physiol Plant 105:746–755

Sippola K, Aro EM (1999) Thiol redox state regulates expression of psbA genes in Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942. Plant Mol Biol 41:425–433

Tsinoremas NF, Schaefer MR, Golden SS (1994) Blue and red light reversibly control psbA expression in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942. J Biol Chem 269:16143–16147

Tsinoremas NF, Kawakami A, Christopher DA (1999) High-fluence blue light stimulates transcription from a higher plant chloroplast psbA promoter expressed in a cyanobacterium, Synechococcus (sp. strain PCC7942). Plant Cell Physiol 40:448–452

Hoffer PH, Christopher DA (1997) Structure and blue-light-responsive transcription of a chloroplast psbD promoter from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol 115:213–222

van Waasbergen LG, Dolganov N, Grossman AR (2002) nblS, a gene involved in controlling photosynthesis-related gene expression during high light and nutrient stress in Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. J Bacteriol 184:2481–2490

Kulkarni RD, Golden SS (1997) mRNA stability is regulated by a coding-region element and the unique 5’ untranslated leader sequences of the three Synechococcus psbA transcripts. Mol Microbiol 24:1131–1142

Mohamed A, Eriksson J, Osievacz HD, Jansson C (1993) Differential expression of the psbA genes in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis-6803. Mol Gen Genet 238:161–168

Salih GF, Jansson C (1997) Activation of the silent psbA1 gene in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp strain 6803 produces a novel and functional D1 protein. Plant Cell 9:869–878

Mohamed A, Jansson C (1989) Influence of light on accumulation of photosynthesis-specific transcripts in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis 6803. Plant Mol Biol 13:693–700

Bouyoub A, Vernotte C, Astier C (1993) Functional analysis of the two homologous psbA gene copies in Synechocystis PCC 6714 and PCC 6803. Plant Mol Biol 21:249–258

Mohamed A, Jansson C (1991) Photosynthetic electron transport controls degradation but not production of psbA transcripts in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis 6803. Plant Mol Biol 16:891–897

Mate Z, Sass L, Szekeres M, Vass I, Nagy F (1998) UV-B-induced differential transcription of psbA genes encoding the D1 protein of photosystem II in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis 6803. J Biol Chem 273:17439–17444

Constant S, Perewoska I, Alfonso M, Kirilovsky D (1997) Expression of the psbA gene during photoinhibition and recovery in Synechocystis PCC 6714: inhibition and damage of transcriptional and translational machinery prevent the restoration of photosystem II activity. Plant Mol Biol 34:1–13

Alfonso M, Perewoska I, Constant S, Kirilowsky D (1999) Redox control of psbA expression in Synechocystis strains. J Photochem Photobiol 48:104–113

Herranen M, Aro EM, Tyystjärvi T (2001) Two distinct mechanisms regulate the transcription of photosystem II genes in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Physiol Plant 112:531–539

Tyystjärvi T, Tyystjärvi E, Ohad I, Aro EM (1998) Exposure of Synechocystis 6803 cells to series of single turnover flashes increases the psbA transcript level by activating transcription and down-regulating psbA mRNA degradation. FEBS Lett 436:483–487

Huang L, McCluskey MP, Ni H, LaRossa RA (2002) Global gene expression profiles of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 in response to irradiation with UV-B and white light. J Bacteriol 184:6845–6858

Tyystjärvi T, Tuominen I, Herranen M, Aro EM, Tyystjärvi E (2002) Action spectrum of psbA gene transcription is similar to that of photoinhibition in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. FEBS Lett 516:167–171

Vass I, Kirilovsky D, Perewoska I, Mate Z, Nagy F, Etienne AL (2000) UV-B radiation induced exchange of the D1 reaction centre subunits produced from the psbA2 and psbA3 genes in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Eur J Biochem 267:2640–2648

Schmetterer GR (1990) Sequence conservation among the glucose transporter from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 and mammalian glucose transporters. Plant Mol Biol 14:697–706

Mulo P, Tyystjärvi T, Tyystjärvi E, Govindjee Mäenpää P, Aro EM (1997) Mutagenesis of the D-E loop of photosystem II reaction centre protein D1. Function and assembly of photosystem II. Plant Mol Biol 33:1059–1071

Mulo P, Laakso S, Mäenpää P, Aro EM (1998) Stepwise photoinhibition of photosystem II. Studies with Synechocystis species PCC 6803 mutants with a modified D-E loop of the reaction center polypeptide D1. Plant Physiol 117:483–490

Komenda J, Hassan HA, Diner BA, Debus RJ, Barber J, Nixon PJ (2000) Degradation of the Photosystem II D1 and D2 proteins in different strains of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803 varying with respect to the type and level of psbA transcript. Plant Mol Biol 42:635–645

Li H, Sherman LA (2000) A redox-responsive regulator of photosynthesis gene expression in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J Bacteriol 182:4268–4277

Kanervo E, Mäenpää P, Aro E (1993) D1 protein degradation and psbA transcript levels in Synechocystis PCC 6803 during photoinhibition in vivo. J Plant Physiol 142:669–675

Mulo P, Eloranta T, Aro E-M, Mäenpää P (1998) Disruption of a spe-like open reading frame alters polyamine content and psbA-2 mRNA stability in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Bot Acta 111:71–76

Alfonso M, Perewoska I, Kirilovsky D (2000) Redox control of psbA gene expression in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803. Involvement of the cytochrome b(6)/f complex. Plant Physiol 122:505–516

El Bissati K, Kirilovsky D (2001) Regulation of psbA and psaE expression by light quality in Synechocystis species PCC 6803. A redox control mechanism. Plant Physiol 125:1988–2000

Tyystjärvi T, Mulo P, Mäenpää P, Aro E-M (1996) D1 polypeptide degradation may regulate psbA gene expression at transcriptional and translational levels in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Photosynth Res 47:111–120

Mohamed A, Eriksson J, Osiewacz HD, Jansson C (1993) Differential expression of the psbA genes in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis 6803. Mol Gen Genet 238:161–168

Eriksson J, Salih GF, Ghebramedhin H, Jansson C (2000) Deletion mutagenesis of the 5’ psbA2 region in Synechocystis 6803: identification of a putative cis element involved in photoregulation. Mol Cell Biol Res Commun 3:292–298

Barnes D, Mayfield SP (2003) Redox control of posttranscriptional processes in the chloroplast. Antioxid Redox Signal 5:89–94

Kulkarni RD, Golden SS (1995) Form II of D1 is important during transition from standard to high light intensity in Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942. Photosynth Res 46:435–443

Sippola K, Aro EM (2000) Expression of psbA genes is regulated at multiple levels in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942. Photochem Photobiol 71:706–714

Tyystjärvi T, Herranen M, Aro EM (2001) Regulation of translation elongation in cyanobacteria: membrane targeting of the ribosome nascent-chain complexes controls the synthesis of D1 protein. Mol Microbiol 40:476–484

Nishiyama Y, Allakhverdiev SI, Yamamoto H, Hayashi H, Murata N (2004) Singlet oxygen inhibits the repair of photosystem II by suppressing the translation elongation of the D1 protein in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Biochemistry 43:11321–11330

Kojima K, Oshita M, Nanjo Y, Kasai K, Tozawa Y, Hayashi H, Nishiyama Y (2007) Oxidation of elongation factor G inhibits the synthesis of the D1 protein of photosystem II. Mol Microbiol 65:936–947

He Q, Vermaas W (1998) Chlorophyll a availability affects psbA translation and D1 precursor processing in vivo in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:5830–5835

Komenda J, Reisinger V, Muller BC, Dobakova M, Granvogl B, Eichacker LA (2004) Accumulation of the D2 protein is a key regulatory step for assembly of the photosystem II reaction center complex in Synechocystis PCC 6803. J Biol Chem 279:48620–48629

Mulo P, Sirpiö S, Suorsa M, Aro EM (2008) Auxiliary proteins involved in the assembly and sustenance of photosystem II. Photosynth Res 98:489–501

Ossenbuhl F, Inaba-Sulpice M, Meurer J, Soll J, Eichacker LA (2006) The Synechocystis sp PCC 6803 oxa1 homolog is essential for membrane integration of reaction center precursor protein pD1. Plant Cell 18:2236–2246

Jansson C, Debus RJ, Osiewacz HD, Gurevitz M, McIntosh L (1987) Construction of an obligate photoheterotrophic mutant of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis 6803: inactivation of the psbA gene family. Plant Physiol 85:1021–1025

Sicora CI, Brown CM, Cheregi O, Vass I, Campbell DA (2008) The psbA gene family responds differentially to light and UVB stress in Gloeobacter violaceus PCC 7421, a deeply divergent cyanobacterium. Biochim Biophys Acta 1777:130–139

Garczarek L, Dufresne A, Blot N, Cockshutt AM, Peyrat A, Campbell DA, Joubin L, Six C (2008) Function and evolution of the psbA gene family in marine Synechococcus: Synechococcus sp. WH7803 as a case study. ISME J 2:937–953

Rappaport F, Guergova-Kuras M, Nixon PJ, Diner BA, Lavergne J (2002) Kinetics and pathways of charge recombination in photosystem II. Biochemistry 41:8518–8527

Kos PB, Deak Z, Cheregi O, Vass I (2008) Differential regulation of psbA and psbD gene expression, and the role of the different D1 protein copies in the cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP-1. Biochim Biophys Acta 1777:74–83

Vass I, Cser K (2009) Janus-faced charge recombinations in photosystem II photoinhibition. Trends Plant Sci 14:200–205

Sicora C, Wiklund R, Jansson C, Vass I (2004) Charge stabilization and recombination in photosystem II containing the D1′ protein product of the psbA1 gene in Synechocystis 6803. Phys Chem Chem Phys 6:4832–4837

Funk C, Wiklund R, Schroder WP, Jansson C (2001) D1’ centers are less efficient than normal photosystem II centers. FEBS Lett 505:113–117

Sicora CI, Appleton SE, Brown CM, Chung J, Chandler J, Cockshutt AM, Vass I, Campbell DA (2006) Cyanobacterial psbA families in Anabaena and Synechocystis encode trace, constitutive and UVB-induced D1 isoforms. Biochim Biophys Acta 1757:47–56

Sander J, Nowaczyk M, Rögner M (2007) Role of the psbA gene family of PSII from the thermophilic cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus elongatus. Photosynth Res 91:176

Paerl HW, Pinckney JL, Steppe TF (2000) Cyanobacterial-bacterial mat consortia: examining the functional unit of microbial survival and growth in extreme environments. Environ Microbiol 2:11–26

Fuhrman JA (1999) Marine viruses and their biogeochemical and ecological effects. Nature 399:541–548

Clokie MR, Mann NH (2006) Marine cyanophages and light. Environ Microbiol 8:2074–2082

Safferman RS, Morris ME (1963) Algal virus: isolation. Science 140:679–680

Mann NH, Cook A, Millard A, Bailey S, Clokie M (2003) Marine ecosystems: bacterial photosynthesis genes in a virus. Nature 424:741

Mann NH, Clokie MR, Millard A, Cook A, Wilson WH, Wheatley PJ, Letarov A, Krisch HM (2005) The genome of S-PM2, a “photosynthetic” T4-type bacteriophage that infects marine Synechococcus strains. J Bacteriol 187:3188–3200

Millard A, Clokie MR, Shub DA, Mann NH (2004) Genetic organization of the psbAD region in phages infecting marine Synechococcus strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:11007–11012

Lindell D, Jaffe JD, Johnson ZI, Church GM, Chisholm SW (2005) Photosynthesis genes in marine viruses yield proteins during host infection. Nature 438:86–89

Lindell D, Sullivan MB, Johnson ZI, Tolonen AC, Rohwer F, Chisholm SW (2004) Transfer of photosynthesis genes to and from Prochlorococcus viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:11013–11018

Sullivan MB, Coleman ML, Weigele P, Rohwer F, Chisholm SW (2005) Three Prochlorococcus cyanophage genomes: signature features and ecological interpretations. PLoS Biol 3:e144

Sullivan MB, Lindell D, Lee JA, Thompson LR, Bielawski JP, Chisholm SW (2006) Prevalence and evolution of core photosystem II genes in marine cyanobacterial viruses and their hosts. PLoS Biol 4:e234

Zeidner G, Bielawski JP, Shmoish M, Scanlan DJ, Sabehi G, Beja O (2005) Potential photosynthesis gene recombination between Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus via viral intermediates. Environ Microbiol 7:1505–1513

Lindell D, Jaffe JD, Coleman ML, Futschik ME, Axmann IM, Rector T, Kettler G, Sullivan MB, Steen R, Hess WR, Church GM, Chisholm SW (2007) Genome-wide expression dynamics of a marine virus and host reveal features of co-evolution. Nature 449:83–86

Clokie MR, Shan J, Bailey S, Jia Y, Krisch HM, West S, Mann NH (2006) Transcription of a ‘photosynthetic’ T4-type phage during infection of a marine cyanobacterium. Environ Microbiol 8:827–835

Sharon I, Tzahor S, Williamson S, Shmoish M, Man-Aharonovich D, Rusch DB, Yooseph S, Zeidner G, Golden SS, Mackey SR, Adir N, Weingart U, Horn D, Venter JC, Mandel-Gutfreund Y, Beja O (2007) Viral photosynthetic reaction center genes and transcripts in the marine environment. ISME J 1:492–501

Bragg JG, Chisholm SW (2008) Modeling the fitness consequences of a cyanophage-encoded photosynthesis gene. PLoS ONE 3:e3550

Hellweger FL (2009) Carrying photosynthesis genes increases ecological fitness of cyanophage in silico. Environ Microbiol (in press)

Acknowledgments

Dr. Taina Tyystjärvi is thanked for critical reading of the manuscript. Research in the authors′ laboratory is financially supported by the Academy of Finland (110099, 118637), Nordic Energy Research Program (BioH2), European FP7 SOLAR-H2 Program (contract 212508), and Maj and Tor Nessling Foundation.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Mulo, P., Sicora, C. & Aro, EM. Cyanobacterial psbA gene family: optimization of oxygenic photosynthesis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 66, 3697–3710 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-009-0103-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-009-0103-6