Abstract

High-latitude environments are warming, leading to changes in biological diversity patterns of taxa. Oomycota are a group of fungal-like organisms that comprise a major clade of eukaryotic life and are parasites of fish, agricultural crops, and algae. The diversity, functionality, and distribution of these organisms are essentially unknown in the Arctic marine environment. Thus, it was our aim to conduct a first screening, using a functional gene assay and high-throughput sequencing of two gene regions within the 18S rRNA locus to examine the diversity, richness, and phylogeny of marine Oomycota within Arctic sediment, seawater, and sea ice. We detected Oomycota at every site sampled and identified regionally localized taxa, as well as taxa that existed in both Alaska and Svalbard. While the recently described diatom parasite Miracula helgolandica made up about 50% of the oomycete reads found, many lineages were observed that could not be assigned to known species, including several that clustered with another recently described diatom parasite, Olpidiopsis drebesii. Across the Arctic, Oomycota comprised a maximum of 6% of the entire eukaryotic microbial community in Barrow, Alaska May sediment and 10% in sea ice near the Svalbard archipelago. We found Arctic marine Oomycota encode numerous genes involved in parasitism and carbon cycling processes. Ultimately, these data suggest that Arctic marine Oomycota are a reservoir of uncharacterized biodiversity, the majority of which are probably parasites of diatoms, while others might cryptically cycle carbon or interface other unknown ecological processes. As the Arctic continues to warm, lower-latitude Oomycota might migrate into the Arctic Ocean and parasitize non-coevolved hosts, leading to incalculable shifts in the primary producer community.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The Arctic is warming at a rapid rate. Elevated atmospheric temperatures and the inflow of warmer waters from the Pacific and Atlantic oceans are reducing sea ice extent and thickness (Vihma 2014). The associated physical changes in the Arctic marine environment are altering the phenology of primary producers (Castellani et al. 2017), their associated consumers, and subsequent higher trophic levels (Feng et al. 2018). As sea surface temperatures continue to increase, southerly Atlantic and Pacific species are migrating north, ushering in novel biological interactions that have unknown consequences on existing Arctic marine food webs (Kortsch et al. 2015). The Arctic Ocean remains one of the least-studied oceanographic regions in the world, with large gaps remaining in the current biodiversity inventory, specifically for microbes. While microbes are estimated to comprise > 90% of all oceanic biomass (Suttle 2007), their activity has yet to be fully integrated into Arctic marine ecology.

Heterotrophic eukaryotic microbes (HEMs), primarily fungi and fungal-like organisms, are known saprotrophs and parasites in freshwater and marine ecosystems (Sparrow 1960; Johnson and Sparrow 1970). Convergent morphology, taxonomy in-flux, and difficulties in cultivation associated with Arctic marine HEMs hinder the identification, characterization, and subsequent integration of their activity into marine systems ecology, especially holistic modeling efforts. As a result, the diversity and distribution of select Arctic marine HEMs is uncharacterized, unreported, or knowingly excluded in published assessments of unicellular eukaryotic biodiversity (Poulin et al. 2011), resulting in a general reductionist understanding of their ecological contributions (Keeling and del Campo 2017).

Oomycota are globally distributed zoosporic heterokonts, previously considered members of the kingdom Fungi, that are now known to phylogenetically branch within the Straminipila-Alveolata-Rhizaria superkingdom (Burki and Keeling 2014). Oomycota have cell walls comprised of cellulose derivatives that serve as structural components, as opposed to chitin in true Fungi (Thines 2018). Oomycota are a genetically and morphologically diverse clade that contains at least 1500 species in 100 genera that can form hyphae or exist as simple holocarpic thalli (Beakes and Thines 2017). Members of Oomycota are known pathogens of nematodes (Phillips et al. 2008), zooplankton (Thomas et al. 2010), micro-algae (Thines et al. 2015, Buaya et al. 2017), and fish (van West 2006). Some diatom-associated Oomycotas have been reported from subarctic marine environments (Hanic et al. 2009; Scholz et al. 2014, 2016), but sparingly from the Arctic Ocean. Specifically, Oomycota have been observed as parasites on algae in the Canadian Arctic (Küpper et al. 2016) and have been reported on marine bird feathers in Svalbard (Singh et al. 2016). Establishing a current inventory of Oomycota appears important and urgent due to the lack of a current baseline and the ongoing northward movement of Atlantic and Pacific species. This migration will lead to novel encounters between parasites and non-coevolved hosts.

To establish a baseline of Oomycota diversity, abundance, and distribution across the Arctic, we conducted high-throughput sequencing of the hypervariable V3–4 and V9 regions of the 18S rRNA gene from sea ice, seawater, and sediment samples across the western Arctic. We supplemented these analyses with a functional gene survey from under-ice Alaskan sediment. We hypothesized that marine Oomycota are widely distributed across the Arctic and encode uncharacterized genetic diversity that facilitates biogeochemical cycling and the turnover of biological material.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Environmental sampling

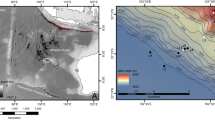

Sea ice, water column and under-ice sediment samples were collected across the Arctic and Bering Sea between 2014 and 2017 (Table 1, Fig. 1) onboard the R/V Polarstern, R/V Sikuliaq, and from snowmobile in the coastal sea ice environments in Alaska, Greenland, and Svalbard. Seawater was collected using a CTD/Rosette sampler in 10 L Niskin bottles. At least 1 liter of seawater was collected to sample the suspended community, which was subsequently vacuum-filtered onto 47 mm, 0.2 μm nuclepore filters (Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany) for high-throughput sequencing. Additional samples were screened with a light microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), and photographed using a digital camera (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Ice cores were extracted at each sea ice station using a 9 cm Kovacs ice corer. The bottom 10 cm of each core was sectioned using an ethanol-sterilized handsaw. Ice core sections were melted at room temperature with the addition of 1 L of 0.22 μm-filtered seawater. After complete melting of the ice cores, samples were vacuum-filtered onto 0.2 μm filters. After filtration, all filters were immediately stored in sterile polypropylene tubes at − 80 °C and kept frozen in the dark until analysis. Sediment traps with 72 mm diameter and 1.8 L volume (Model 28.xxx series, KC-Denmark, Silkeborg, Denmark) were deployed at 5 and 20 m for 8 h and 37 min at a single ice station (station 80). Sediment samples were collected in Barrow, Alaska in triplicate in May and June of 2014 using a ponar grab that was deployed through a hole in the ice. Sediment was stored in sterile polypropylene tubes at − 80 °C until DNA extraction.

Sampling sites of sea ice, seawater, and sediment across the Arctic, including the Bering Sea, Greenland and Svalbard. Note that Barrow, Alaska has been sampled several times (see Table 1)

DNA extraction and sequence processing

DNA was extracted and PCR-amplified, as previously described (Hassett and Gradinger 2016; Hassett et al. 2017). Briefly, we used primers that target three separate hypervariable regions of the 18S rRNA gene. We generated ~ 400 base pair sequences from the V3-V4 regions using the 18S-82F (5′-GAAACTGCGAATGGCTC-3′) and Ek-516R (5′-ACCAGACTTGCCCTCC-3′) primer pair. This primer pair was used primarily to deep-sequence (six samples per MiSeq run) samples from Barrow, Alaska, plus one sample from Svalbard and to obtain sequences informative enough for phylogenetic inference. To supplement this analysis, we generated ~ 170 base pair sequences from the V9 region using the Euk1391f: (5′- GTACACACCGCCCGTC-3′) and EukBr: (5′- TGATCCTTCTGCAGGTTCACCTAC-3′). This primer pair was used for spatial analysis. PCR products were generated using fusion primers with the Fluidigm CS1 or CS2 universal oligomers added to 5′ ends. Secondary PCR and sequencing was performed at Michigan State University’s Genomics Core Lab. Secondary PCR was conducted with dual-indexed, Illumina-compatible primers to complete library construction. Final PCR products were batch-normalized using an Invitrogen SequalPrep DNA Normalization plate and products recovered from the plate were then pooled. The pool was quantified using a combination of Qubit dsDNA HS, Agilent Bioanalyzer DNA 1000, and Kapa Illumina Library Quantification qPCR assays. The pool was loaded onto two (i.e. sequenced twice to increase sequencing depth) standard MiSeq v2 flow cells and sequencing was performed in a 2x250bp paired-end format using MiSeq v2 500 cycle reagent cartridges. CPCustom primers for sequence reads one and two, as well as index read one that was complementary to the Fluidigm CS1 and CS2 oligos, were added to appropriate wells of the reagent cartridge. Base calling was done by Illumina Real Time Analysis (RTA) v1.18.54 and the output was demultiplexed and converted to FastQ format with Bcl2fastq v2.19.1. Sequence analysis and clustering was conducted using Mothur v1.33.3 (Schloss et al. 2009; Kozich et al. 2013). Sequences with ambiguous base calls were eliminated (maxambig = 0) from all datasets. Sequences were aligned using the SILVA (Quast et al. 2013) reference database (Release 123), screened for chimeras (Edgar et al. 2011) and classified with SILVA (Release 123), using the K-nearest neighbor algorithm (bootstrap cutoff value of 75% with 1,000 iterations). Sequences classified as Bacteria, Archaea, and Metazoans were removed from datasets before analysis. The remaining sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at a 97% similarity cutoff and used for further analyses.

Functional gene survey

For functional gene analysis, DNA was extracted from triplicate under-ice sediment samples from Barrow, Alaska collected in May and June 2014. After extraction, DNA was pooled and analyzed using the GeoChip (He et al. 2007) functional gene microarray (GeoChip 5.0; Glomics Inc., Norman, OK). Amplification, labeling, hybridization, imaging, and data processing were conducted by the Institute for Environmental Genomics at the University of Oklahoma according to published protocols (Van Nostrand et al. 2016). Signal intensity was normalized to display all positive probes detected in each sample. Probe data were removed from the output if the signal to noise ratio was below 2 or if the signal was < 200 or < 1.3 times the background.

Phylogeny

After OTU clustering of our V3-V4 sequences, the top 100 most-abundant Oomycota taxa from across the Arctic were aligned using MUSCLE as implemented in MEGA7 v7.0.26 (Kumar et al. 2016). Sequences from Miracula helgolandica, Olpidiopsis drebesii, and reference sequences obtained from NCBI by manual selection for a balanced representation of the known oomycete orders, as well as using the TrEase webserver (http:// thines-lab.senckenberg.de/trease) were added to the OTU sequences. This database was then aligned with a gap opening penalty of − 400 and a gap extension penalty of − 4. Leading and trailing sequences were end-trimmed to assure that tests of molecular phylogeny analyzed overlapping regions. The Minimum Evolution algorithm was used to test phylogenetic inference with 500 bootstraps and all values set to default, except for the selection of the Tamura-Nei substitution model. The resulting alignment is supplied as Additional file 1. Trees were visualized and edited in MEGA and exported as vector graphic for further editing.

RESULTS

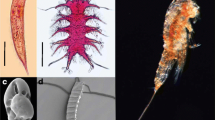

A quick screening of environmental samples revealed diatoms that were parasitized by members of Oomycota (Fig. 2). These observations are in-line with a relatively high proportion of oomycete reads found in the DNA sequencing approach. Specifically, after V3-V4 sequence processing and removal of prokaryote and metazoan sequences, 16,351,684 unique DNA sequence reads were retained for analysis. Of these, 290,077 (1.7%) were classified as Oomycota. Oomycota were detected in every sample, both sediment and sea ice communities, in coastal Alaskan marine environments. In these systems, the Oomycota generally comprised a greater proportion of total reads in sediment communities (average relative abundance (ARA) = 2.0%; standard deviation (SD) = 1.9), relative to sea ice (ARA = 0.3%; SD = 0.4). Oomycota contributed a maximum of 5.7% of the total eukaryotic microbial community in May sediment and a maximum of 0.9% of total eukaryotic microbial community in April sea ice. Nearly the entire community of Oomycota sequences (92.7%) was represented by unclassifiable sequences, while the remaining sequences were classified as Aphanomyces, Aplanopsis, Halipththoros, Halocrusticida, Halophytophthora, Lagenidium, Leptolegnia, Olpidiopsis, Pythium, and Saprolegnia. Phylogenetic inference of Oomycota-allied DNA data revealed that approximately 50% of the sequences corresponded to the recently-described diatom parasite M. helgolandica, which is not yet integrated into HTS classification databases (Fig. 3).

Seasonal relative abundance of the top 100 Oomycota V3-V4 OTUs detected in Barrow, Alaska, as well as one site in Svea, Svalbard (May of the same year). The classification scheme corresponds to phylogenetic position of 18S rRNA V3-V4 OTUs, as these sequences were unidentifiable with a Bayesian classification method

After V9 sequence processing and removal of prokaryotes and metazoan sequences, 16,456,575 sequences were retained for analysis. Of these, 130,186 (0.8%) sequences were classified as Oomycota. Oomycota were detected in all sites, except three chlorophyll maxima samples (sites 43, 80, Deep Water Basin). Oomycota had higher relative abundances in sea ice communities (ARA = 1.1%; SD = 2.5), compared to surface seawater (ARA = 0.02%; SD = 0.03), chlorophyll maxima (ARA = 0.1%; SD = 0.3), and bottom communities (ARA = 0.9%; SD = 1.9). They contributed a maximum proportion of 9.5% of the total eukaryotic microbial community from sea ice station 66. Nearly the entire community of Oomycota sequences (99%) were represented by unclassifiable sequences, while the remaining sequences were classified as Halocrusticida and Pythium. However, it needs to be noted that the short sequences are more difficult to phylogenetically assign and that there is, as yet, no reference sequence for available for the 18S rRNA V9 region of M. helgodandica. One Oomycota sequence was observed in the 20 m sediment traps and 28 sequences were obtained from the 5 m trap.

Operational taxonomic unit clustering of the V3-V4 region identified 36,691 distinct Oomycota taxa (32,294 singletons). The two most abundant V3-V4 OTUs were observed 127,754 times (42% of all Oomycota observations). The top-100 most abundant V3-V4 OTUs were phylogenetically analyzed. After end-trimming the V3-V4 alignment had 408 sites. The phylogenetic reconstruction revealed that the majority of our top-100 abundant OTUs were present in three major groups that branch basal to the crown oomycetes (Fig. 4). These clades represented a strongly supported group around M. helgolandica (a parasite of Pseudonitzschia diatoms) that contained the three most abundant OTUs, an unsupported, paraphyletic group around O. heterosiphoniae (a parasite of red algae), and a weakly supported clade around O. drebesii (a parasite of Rhizosolenia diatoms). Specifically, the top-two most abundant OTUs represent M. helgolandica, identified by manual curation. The third most-abundant V3-V4 OTU represents an unknown lineage of Miracula and was detected every month in both sea ice and under-ice sediment. Only one of the 100 most abundant OTUs clustered with the crown oomycetes and was identified as a member of the genus Atkinsiella, which contains holocarpic parasites of crustaceans.

Biogeographical assessment of our 18S sequences revealed a broad-distribution of many taxa across the Arctic Ocean. Specifically, comparative analysis of all Oomycota-classified V3-V4 OTUs from our samples revealed 52 OTUs that were found in both Svalbard and Barrow, Alaska. V9 analysis revealed that the most abundant OTU was detected in both the Gulf of Alaska, as well as Svalbard. Three V9 OTUs, comprising 17 observations, were found exclusively in the Bering Sea.

The GeoChip 5.0 contains 167,403 unique probes (many copies of the same gene derived from different species) to which environmental DNA can hybridize. Environmental DNA from Barrow, Alaska sediment hybridized to 63,403 (37%) of the available GeoChip probes. May sediment DNA hybridized to available 56,729 probes and 55,723 probes hybridized to June sediment DNA. Detected genes are characterized as being involved in biogeochemical cycling of carbon, nitrogen, sulphur, phosphorous, as well as in natural product synthesis. Genes from each taxonomic domain of Life were detected, hybridizing to: 22% of possible viral probes, 30% of eukaryotic probes, 41% of bacterial probes, and 29% of Archaea probes. Oomycota were represented by 110 probes (39% of all available Oomycota probes) that were derived from Achlya, Aphanomyces, Hyaloperonospora, Phytophthora, Pythium, and Saprolegnia. These hybridized Oomycota probes are characterized as being involved in carbon cycling, nitrate assimilation, sulphur assimilation, metal homeostasis, and virulence (Table 2). The most abundant Oomycota genes were pectate lyase and INF1 elicitin. Of all available probes, Oomycota pectate lyase was the 408th most-abundant gene detected in May sediment; and the Oomycota-derived INF1 elicitin gene was the 267th most-abundant gene detected in June sediment.

TAXONOMY

Not applicable.

DISCUSSION

The Oomycota are common members of freshwater aquatic ecosystems and terrestrial environments that interface degradation processes and establish symbiotic relationships with a variety of organisms (Thines 2014). In the marine environment, the diversity and functioning of Oomycota is poorly understood. However, many Oomycota are described as pathogens of algae (Beakes and Thines 2017, Tsirigoti et al. 2013, Li et al. 2010). In the Arctic Ocean and other high-latitude environments, reports of Oomycota are sparse and sporadic; consequently, the diversity, functioning, and general ecology of this important group of organisms is largely unknown.

OTU clustering and analysis revealed a broad distribution of several Oomycota across the Arctic Ocean, underscoring that Arctic oomycetes are both widespread and present in diverse environments. Both of our primer sets identified Oomycota taxa that were shared between sites in Alaska and those in Svalbard (> 5000 km distance). In general, our 18S rRNA sequencing data indicated a consistently low (< 1%) contribution of Oomycota-classified sequences relative to other eukaryotic microbial organisms. However, under specific environmental conditions, these proportions approached 10% of the eukaryotic microbial community. Phylogenetic analysis of the 100 most abundant V3-V4 OTUs revealed that manysequences could not be assigned to any known oomycete species. These data indicate that Arctic marine Oomycota are a reservoir of undescribed biodiversity, even though only the top-100 most abundant OTUs were analyzed in this study. Though many detected DNA sequences represent potentially novel lineages, most OTUs phylogenetically branched into three major groups, all of which contain species described as holocarpic pathogens of photosynthetic organisms. The most abundant oomycete OTUs that we found were closely related or conspecific with Miracula helgolandica, a recently-described parasitoid of Pseudonitzschia diatoms, known from temperate coastal waters of Canada (Hanic et al. 2009) and Germany (Buaya et al. 2017). Sequences allied to M. helgolandica contributed ~ 50% of all the oomycete V3-V4 dataset reads. In addition to M. helgolandica s. lat., at least two additional, still undescribed, species are present, one of which is represented by the 3rd most abundant V3-V4 OTU. Another major clade contained the recently described O. drebesii (Buaya et al. 2017), with more than a dozen independent lineages that might represent additional undescribed diatom parasitoids. The third major phylogentic group that we detected is less well-defined, but includes a parasite of red algae, rendering it tempting to speculate that the lineages found within it could also be pathogens of multicellular algae. In-line with recent studies that add evidence to the widespread presence of oomycete parasitoids in marine plankton (Hanic et al. 2009; Scholz et al. 2016; Buaya et al. 2017), our data suggest that many marine Oomycota are likely pathogenic. If true, Oomycota could play an important ecological role in marine environments by constraining primary producer biomass, while contributing to the carbon flow in marine food webs through mechanisms analagous to the mycoloop (Kagami et al. 2014). Moreover, the detection of several Oomycota OTUs in only the Bering Sea suggests that lower-latitude Oomycota could migrate into the warming Arctic Ocean, thereby interacting with non-coevolved hosts, leading to unforeseeable changes in the communities of primary producers.

The functional gene microarray from under-ice marine sediment in Barrow, Alaska identified a number of genes involved in biogeochemical cycling and parasitism. Some of these biogeochemical cyling genes are known to be involved in carbohydrate metabolism (mannase, oxylose isomerase, and pectate lyase), as well as the degradation recalcitrant materials, such as chitin (chitinase). While the presence of these genes is not surprising, their detection in sediment provides empirical evidence from the Arctic Ocean to support Oomycota-mediated carbon cycling. Substantial coupling between benthic and sea ice environments, especially in coastal environments, (Søreide et al. 2013, Gradinger et al. 2009), suggests these processes are also catalyzed in the sympagic system. In addition to common carbon cycling gene products, we detected a number of gene products associated with pathogenicity. Specifically, we detected INF1, which encodes for a secreted protein that can induce a hypersensitive response in plants, thereby causing necrosis, but also confining the pathogen. INF1 was first characterized in Phytophthora infestans, the causal agent of potato late blight Surprisingly, we detected high levels of INF1 in seafloor sediment, providing early evidence that INF1 variants are important and evolutionarily conserved proteins in oomycetes. However, the function of INF1 variants in holocarpic organisms is unknown. It is conceivable that pathogenicity of marine oomycetes is similarly complex to terrestrial oomycetes (Gachon et al. 2009). In our preliminary microscopic screening, Oomycota-parasitizing diatoms were observed in the Arctic Ocean, but these microscopic observations need to be confirmed with a dedicated systematic screening approach. Future research should focus on exploring the seasonal dynamics of host and associated oomycete parasites, the molecules that interface these biological interactions, and ultimately the proportion of resistant and susceptible variants within these species.

Collectively, the data presented in this study provides a baseline of Oomycota diversity, distribution, and putative functioning in the Arctic marine environment that opens the door for future studies to explore the disease ecology of Oomycota and to eventually place them into a larger trophic and evolutionary framework.

CONCLUSIONS

Oomycetes exist throughout the Arctic marine realm and can seasonally comprise > 5% of 18S rRNA amplicon sequence reads. Arctic marine oomycetes parasitize diatoms and encode genes responsible for interfacing virulence and biogeochemical cycling processes. As the Arctic continues to warm, lower-latitude Oomycota might migrate into the Arctic Ocean and parasitize non-coevolved hosts.

Abbreviations

- ARA:

-

Average relative abundance

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- HEM:

-

Heterotrophic eukaryotic microbes

- OTU:

-

Operational taxonomic unit

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- rRNA:

-

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- V:

-

Variable

References

Beakes GW, Thines M (2017) Hyphochytridiomycota and Oomycota. In: Archibald et al (eds) Handbook of the Protists. Springer International Publishing, New York, pp 435–505

Buaya AT, Ploch S, Hanic L, Nam B, Nisgrelli L et al (2017) Phylogeny of Miracula helgolandica gen. Et sp. nov. and Olpidiopsis drebesii sp. nov,. Two basal oomycete parasitoids of marine diatoms, with notes on the taxonomy of Ectrogella-like species. Mycological Progress 16:1041–1050

Burki F, Keeling PJ (2014) Rhizaria. Current Biology 24:pR103–pR107

Castellani G, Losch M, Lange BA, Flores H (2017) Modeling Arctic Sea-ice algae: physical drivers of spatial distribution and algae phenology. Journal of Geophysical Research Oceans 122:7466–7487

Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC et al (2011) UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27:2194–2200

Feng Z, Ji R, Ashjian C, Campbell R, Zhang J (2018) Biogeographic responses of the copepod Calanus glacialis to a changing Arctic marine environment. Global Change Biology 24:e159–e170

Gachon CMM, Strittmatter M, Muller DG et al (2009) Detection of differential host susceptibility to the marine oomycete pathogen Eurychasma dicksonii by real-time PCR: not all algae are equal. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 75:322–328

Gradinger R, Kaufman MR, Bluhm BA (2009) Pivotal role of sea ice sediments in the seasonal development of near-shore Arctic fast ice biota. Marine Ecological Progress Series 394:49–63.

Hanic LA, Sekimoto S, Bates SS (2009) Oomycete and chytrid infections of the marine diatom Pseudo-nitzschia pungens (Bacillariophyceae) from Prince Edward Island, Canada. Canadian Journal of Botany 87:1096–1105

Hassett BT, Ducluzeau AL, Collins RE, Gradinger R (2017) Spatial distribution of aquatic marine fungi across the western Arctic and sub-Arctic. Environmental Microbiology 19:475–484

Hassett BT, Gradinger R (2016) Chytrids dominate Arctic marine fungal communities. Environmental Microbiology 18:2001–2009

He Z, Gentry TJ, Schadt CW et al (2007) GeoChip: a comprehensive microarray for investigating biogeochemical, ecological and environmental processes. ISME Journal 1:67–77

Johnson TW, Sparrow FK (1970) Fungi in oceans and estuaries. J. Cramer, Weinheim

Kagami M, Miki T, Takimoto G (2014) Mycoloop: chytrids in aquatic food webs. Frontiers in Microbiology 5:155.

Keeling PJ, del Campo J (2017) Marine protists are not just big bacteria. Current Biology 27:pr541–pR549

Kortsch S, Primicerio R, Fossheim M, Dolgov AV, Aschan M (2015) Climate change alters the structure of arctic marine food webs due to poleward shifts of boreal generalists. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 282:2015146

Kozich JJ, Westcott SL, Baxter NT, Highlander SK, Schloss PD (2013) Development of a dual-index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 79:5112–5120

Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K (2016) MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Molecular Biology and Evolution 33:1870–1874

Küpper FC, Peters AF, Shewring DM, Sayer MDJ, Mystikou A et al (2016) Arctic marine phytobenthos of northern Baffin Island. Journal of Phycology 52:532–549

Li W, Zhang T, Tang X, Wang B (2010) Oomycetes and fungi: important parasites on marine algae. Acta Oceanologica Sinica 29:74–81

Phillips AJ, Anderson VL, Robertson EJ, Secombes CJ, van West P (2008) New insights into animal pathogeneic oomycetes. Trends in Microbiology 16:13–19

Poulin M, Daugbjerg N, Gradinger R, Ilyash L, Ratkova T, von Quillfeldt C (2011) The pan-arctic biodiversity of marine pelagic and sea-ice unicellular eukaryotes: a first attempt assessment. Marine Biodiversity 41:13–28

Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, Pelin Y, Gerken J et al (2013) The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Research 41:D590–D596

Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M et al (2009) Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 75:7537–7541

Scholz B, Guilou L, Marano AV, Neuhauser S, Sullivan BK et al (2016) Zoosporic parasites infecting marine diatoms - a black box that needs to be opened. Fungal Ecology 19:59–76

Scholz B, Küpper FC, Vyverman W, Karsten U (2014) Eukaryotic pathogens (Chytridiomycota and Oomycota) infecting marine microphytobenthic diatoms - a methodological comparison. Journal of Phycology 50:1009–1019

Singh SM, Tsuji M, Gawas-Sakhalker PJ, Loonen MJJE et al. (2016) Bird feather fungi from Svlabard Arctic. Polar Biology 39:523–532.

Sparrow FK (1960) Aquatic Phycomycetes. The University of Michigan press, Ann Arbor

Søreide JE, Carroll ML, Hop H, Ambrose WG, Hegseth EN, et al. (2013) Sympagic-pelagic-benthic coupling in Arctic and Atlantic waters around Svalbard revelaed by stable isotopic and fatty acid tracers. Marine Biology Research 9:831–850.

Suttle CA (2007) Marine viruses – major players in the global ecosystem. Nature Reviews Microbiology 5:801–812

Thines M (2014) Phylogeny and evolution of plant pathogenic oomycetes — a global overview. European Journal of Plant Pathology 138:431–447

Thines M (2018) Oomycetes. Current Biology 28:R812–R813

Thines M, Nam B, Nigrelli L, Beakes G, Kraberg A (2015) The diatom parasite Lagenisma coscinodisci (Lagenismatales, Oomycota) is an early diverging lineage of the Saprolegniomycetes. Mycological Progress 14:75

Thomas SH, Housley JM, Reynolds AN et al (2010) The ecology and phylogeny of oomycete infections in Asplanchna rotifers. Freshwater Biology 56:384–394

Tsirigoti A, Kuepper FC, Gachon CMM, Katsaros C (2013) Filementous brown algae infected by the marine, holocarpic oomycete Eurchasma dicksonii. Plant Signaling and Behavior 8:e26367

Van Nostrand JD, Yin H, He Z, Zhou J (2016) Hybridization of environmental microbial community nucleic acids by GeoChip. Methods in Molecular Biology 1399:183–196

van West P (2006) Saprolegnia parasitica, an oomycete pathogen with a fishy appetite: new challenges for an old problem. Mycologist 20:99–104

Vihma T (2014) Effects of Arctic Sea ice decline on weather and climate: a review. Surveys in Geophysics 35:1175–1214

Acknowledgements

We greatly acknowledge the support of the science team and the crew of R/V Polarstern and grant support from AWI_PS106_00. Many thanks to Renate Osvik for her photographic contributions of Oomycetes.

Funding

B.H. is supported by the Norwegian Arctic Seasonal Ice Zone Ecology (SIZE) group, which is jointly funded by UiT the Arctic University of Norway and the Tromsø Research Foundation (project number 01vm/h15). Grant funding from the US National Science Foundation (Award no. 1303901) supported the collection and processing of some of these data. A.B. is supported by a KAAD PhD fellowship, and this study was partially supported by the LOEWE Center for Translational Biodiversity Genomics (TBG), funded by the Government of Hessen. The funders had no role in study design, interpretation of data or the preparation of the present manuscript.

Adherence to national and international regulations

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Microarray data were deposited in NCBI Geo under accessions GSE117831, GSM3309953, and GSM3309954. Sequences were deposited in SRA (SAMN03769253-SAMN03769264 for V3-V4 sequences, SAMN04332622-SAMN04332627 and SAMN08888854- SAMN08888884 for V9 sequences).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BH conducted field sampling and bioinformatics. BH and MT conducted molecular phylogeny. All authors contributed to the interpretation of these data and the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This work conforms with all regulations pertaining to ethics approval and the consent to participate. In general, this is not applicable to our study, as there were no human subjects subject to research.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Alignment used in this study. (FAS 90 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hassett, B.T., Thines, M., Buaya, A. et al. A glimpse into the biogeography, seasonality, and ecological functions of arctic marine Oomycota. IMA Fungus 10, 6 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43008-019-0006-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43008-019-0006-6