Abstract

Introduction

Although the prevalence of underweight is declining among Indian women, the prevalence of overweight/obesity is increasing. This study examined the prevalence and factors associated with underweight and overweight/obesity among reproductive-aged (i.e., 15–49 years) women in India.

Methods

This cross-sectional study analyzed data from the 2015–16 National Family Health Survey. The Asian and World Health Organization (WHO) recommended cutoffs for body mass index (BMI) were used to categorize body weight. The Asian and WHO BMI cutoffs for combined overweight/obesity were ≥ 23 and ≥ 25 kg/m2, respectively. Both recommendations had the same cutoff for underweight, < 18.5 kg/m2. After prevalence estimation, logistic regression was applied to investigate associated factors.

Results

Among 647,168 women, the median age and BMI was 30 years and 21.0 kg/m2, respectively. Based on the Asian cutoffs, the overall prevalence of underweight was 22.9%, overweight was 22.6%, and obesity was 10.7%, compared to 15.5% overweight and 5.1% obesity as per WHO cutoffs. The prevalence and odds of underweight were higher among young, nulliparous, contraceptive non-user, never-married, Hindu, backward castes, less educated, less wealthy, and rural women. According to both cutoffs, women who were older, ever-pregnant, ever-married, Muslims, castes other than backwards, highly educated, wealthy, and living in urban regions had higher prevalence and odds of overweight/obesity.

Conclusion

The prevalence of both non-normal weight categories (i.e., underweight and overweight/obesity) was high. A large proportion of women are possibly at higher risks of cardiovascular and reproductive adverse events due to these double nutrition burdens. Implementing large-scale interventions based on these results is essential to address these issues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Overweight/obesity is a leading risk factor for global death and disability, and is associated with various non-communicable diseases including hypertension, diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disorders [1,2,3]. Globally, about one-third of adults are overweight/obese and about 10% of adults are underweight [4, 5]. Due to differences in biological (e.g., hormones) and behavioral characteristics (e.g., food deprivation during childhood and insufficient physical activity), females are more prone to being underweight, overweight and obese compared to their male counterparts [6,7,8,9]. Women with extreme body weight categories (i.e., underweight and overweight/obesity) suffer from infertility and adverse perinatal outcomes including abortion, preterm birth, and neonatal mortality [10,11,12,13]. Maternal obesity is associated with childhood obesity as well [14, 15]. Recent estimates suggest that the proportion of overweight/obese women is increasing alarmingly in most low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) due to current demographic transitions in these countries [5, 6]. For instance, a recent study conducted by Chowdhury et al. found that the prevalence of overweight/obesity increased from 9 to 39% in Bangladesh [16]. Another study by Vaidya et al. had similar results in Nepal [17].

With a population over 1 billion people, India is no exception to the trend of rising prevalence of overweight/obesity [18, 19]. This country is dealing with the double nutrition burden of underweight and overweight/obesity, and although among women of reproductive age, the prevalence of underweight has declined from 36% in 2005–06 to 23% in 2015–16, the prevalence of overweight/obesity has increased from 13% in 2005–06 to 21% in 2015–16 [19, 20]. In addition, more than half of the women in India are of reproductive age (i.e., 15–49 years), which represents about 250 million women [21]. To improve maternal and child health as well as the nutritional status of the overall population, it is particularly important to evaluate the nutritional status of reproductive-aged women. However, few studies have investigated prevalence and correlates of underweight and overweight/obesity among women in this age group with a nationally representative dataset in India. In this study, we address these existing gaps in the literature by investigating the prevalence and associated factors of extreme body weight categories among women of reproductive age in India.

Methods

Data source

This cross-sectional study used data from the 2015–16 National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4). The NFHS-4 was a nationally-representative survey and covered all states to obtain data on major health indicators in India, including maternal and child health indicators. The International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) implemented this survey from January 2015 to December 2016. In-person household interviews were conducted. The ethical approval for the survey was provided by Institutional Review Boards from the IIPS and ICF International. Verbal informed consent was obtained from respondents aged ≥18 years. If the respondent’s age was 15–17 years, consent was obtained from a legal guardian in addition to assent from the respondent. Details of this survey including methodologies, data collection, sample size, and findings are reported elsewhere [20]. The electronic approval to use the data was obtained from ICF International, Rockville, Maryland, USA in October 2018.

Briefly, the NFHS-4 involved two-stage sampling. The survey used the 2011 census as the sampling frame. Villages and census enumeration blocks (CEBs) served as the primary sampling units (PSUs) in rural and urban areas, respectively. With the probability proportional to size (PPS), villages were selected from the sampling frame. Based on the estimated number of households in a village, three substrata were created. Next, two more substrata were created based on the proportion of people representing scheduled castes and scheduled tribes (SCs/STs). The first three substrata were then crossed with the second two substrata to create six equal-sized strata. In urban regions, based on the proportion of SC/ST population, the CEBs were sorted. Then, the PPS sampling was used to select sample CEBs [20].

Complete mapping and listing of households were done in all PSUs. PSUs with ≥300 households were segmented into 100–150 households. Using systematic sampling with PPS segments, two segments were selected from those PSUs (i.e., PSUs with ≥300 households). Thus, either a PSU or a PSU segment made a cluster. In every selected cluster of both regions, 22 households were selected with systematic sampling. The total number of selected, occupied, and interviewed households was 628,900, 616,346, and 601,509, respectively. The overall response rate was 98% [20].

Study variables

Body weight categories are commonly reported by body mass index (BMI). This is the ratio of weight (in kilograms), and height squared (in meters), usually expressed as kg/m2. Although the BMI cutoff to classify underweight is almost universal (i.e., < 18.5 kg/m2), two cutoffs are used to classify overweight and obesity [22]. The World Health Organization (WHO) uses the BMI cutoffs of 25–29.9 and ≥ 30 kg/m2 to categorize overweight and obesity, respectively. Since Asian people have higher cardiovascular and diabetes risks with a lower BMI, the suggested cutoffs for Asian people are 23–27.4 kg/m2 for overweight and ≥ 27.5 kg/m2 for obesity [22]. Considering the importance of both cutoffs, this study reported the prevalence and associated factors based on both cutoffs.

In this survey, the Seca 874 digital scale was used to measure weight and the Seca 213 stadiometer was used to measure height [20]. Trained survey staff obtained the measurements for a single time. BMI was rounded to the nearest hundredth decimal place. All pregnant women were excluded from prevalence estimates [20]. Explanatory variables were selected based on published reports and the dataset’s structure. Participants reported their age, sex, marital status, education level (i.e., no formal education, primary, secondary, and college or above), current hormonal contraceptive use, castes (i.e., SC, ST, other backward classes or others), and religion (i.e., Hindu, Muslim or others). The wealth status was obtained by principal component analysis of basic household construction materials and households elements [20]. Regarding location, place (i.e., rural or urban) and region of residence was obtained. Additional file 1: Table S1 describes all study variables.

Data analysis

Stata 14.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas) was used to analyze data. Respondents’ background characteristics were reported by their weight classification according to both cutoffs. After assessing the normality of continuous variables, median and interquartile ranges (IQR) were used to describe them; categorical variables were reported by weighted numbers and percentages. The overall weighted prevalence (with 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) of underweight, overweight and obesity was reported based on background characteristics with both recommended cutoffs. Then, using ‘normal weight’ as the reference category of both cutoffs, simple and multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted to investigate the associated factors of ‘underweight’ and ‘combined overweight/obesity’. Variables significant in unadjusted analysis were considered for incorporation into the multivariable analysis. Crude odds ratios (CORs) and adjusted odds ratios (AORs) were reported separately for both cutoffs. Multicollinearity was assessed by variance inflation factors (VIF); explanatory variables with VIF ≥10 were considered for removal from the multivariable model. We accounted for the cluster-sampling design of the NFHS-4 to obtain all weighted prevalence and associated factors.

Results

Table 1 shows the background characteristics of the respondents. Among 647,168 women, 148,115, 215,652, and 133,748 were underweight, overweight/obese as per the Asian cutoff, and overweight/obese as per the WHO cutoff, respectively. The median age of the women was 30 years (IQR: 22–38), the underweight participants had a lower median age compared to overweight/obese women as per both cutoffs. About 70% of the women were pregnant at least once in their life. The overall proportion of contraceptive-using women was 4.5%. Overweight/obese women as per both Asian and WHO cutoffs had a higher proportion of contraceptive users compared to underweight women, 5.3, 5.1, and 3.1%, respectively. Approximately 23.8% of women were never-married; they composed a larger proportion of underweight women compared to overweight/obese women. The proportion of Hindu respondents was 80.7%; the underweight women had the highest proportion of Hindu women. Similarly, about 73.0% of respondents were from 1 of the 3 backward classes. Although the overweight/obese women as per both cutoffs had a higher proportion of women from upper wealth quintiles, the underweight women had a higher share from the lower two wealth quintiles. More than three-fourths of the underweight women were from rural areas (76.7%), while around half of the overweight/obese women were from rural areas (52.1 and 47.8% according to Asian and WHO cutoffs, respectively). About one-fourth of the women were from the Northern region (23.2%).

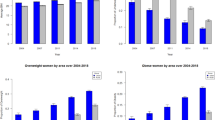

Table 2 describes the prevalence according to different cutoffs. The prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity as per the Asian cutoffs, and overweight and obesity as per the WHO cutoffs was 22.9% (95% CI: 22.7–23.1), 22.6% (95% CI: 22.5–22.8), 10.7% (95% CI: 10.5–10.8), 15.5% (95% CI: 15.4–15.7), and 5.1% (95% CI: 5.0–5.3), respectively. The prevalence of underweight declined with age while the prevalence of overweight/obesity increased with age as per both cutoffs. Ever-pregnant women had an increased prevalence of overweight/obesity compared to never-pregnant women as per both cutoffs. According to both the Asian and WHO cutoffs, women who reported that they were using a hormonal contraceptive had a higher prevalence of overweight and obesity while the prevalence of underweight was higher among women who were not using a hormonal contraceptive. The 3 backward classes (i.e., scheduled caste, scheduled tribe, and other backward classes) had increased prevalence of underweight, although classes other than these backward classes had increased prevalence of overweight/obesity as per both Asian and WHO cutoffs. As per both cutoffs, from the poorest to the richest wealth quintile, the prevalence of overweight and obesity increased; however, the prevalence of underweight was in reverse direction (i.e., decreased). Education level showed similar trends in prevalence. In urban regions, the Asian cutoffs’ prevalence was 28.6% (95% CI: 28.2–29.1) for overweight and 17.7% (95% CI: 17.3–18.1) for obesity, while the WHO cutoffs’ prevalence was 22.2% (95% CI: 21.8–22.6) for overweight and 9.1% (95% CI: 8.8–9.4) for obesity; the proportion of people with overweight/obesity was higher in urban regions compared to rural regions as per both cutoffs. The prevalence of underweight was higher in rural regions compared to urban regions (26.8% vs 15.5%). The highest prevalence of underweight was observed in Central region, 27.9% (95% CI: 27.5–28.4). Figure 1 and Additional file 1: Fig. S1 summarized the overall prevalence.

Table 3 presents the CORs and AORs of the factors associated with underweight as per both cutoffs. With decreasing age, the odds of underweight increased, with the highest odds of underweight among the women of 15–19 years according to both Asian (AOR: 2.07, 95% CI: 2.00–2.13) and WHO (AOR: 2.58, 95% CI: 2.51–2.66) cutoffs. The number of pregnancies also had a significant association with underweight. Women who were not using hormonal contraceptives had greater odds of underweight according to both Asian (AOR: 1.17, 95% CI: 1.13–1.21) and WHO (AOR: 1.20, 95% CI: 1.16–1.24) cutoffs. Although being a married woman was protective against underweight as per the Asian cutoff, being a never-married woman was a factor associated with increased underweight per both cutoffs. Both Muslim and Hindu women were more likely to be underweight compared to women belonging to other religions. Based on both cutoffs, all socioeconomic variables were significantly associated with underweight; women with lower household wealth quintiles, education level, and backward classes had positive association with underweight compared to women with the richest wealth quintile, higher education level and other classes, respectively. Rural women had increased odds of underweight as per both Asian (AOR: 1.06, 95% CI: 1.04–1.08) and WHO (AOR: 1.09, 95% CI: 1.07–1.11) cutoffs compared to urban women. Region of residence was also a significant variable.

In Table 4, the results of logistic regression analyses to investigate potential correlates of overweight/obesity are presented. All variables that were associated with underweight were also associated with overweight/obesity as per both cutoffs. Women with the highest age (i.e., 40–49 years) had the highest odds of overweight/obesity as per both Asian (AOR: 5.00, 95% CI: 4.84–5.17) and WHO (AOR: 5.38, 95% CI: 5.15–5.61) cutoffs. Women with 1–4 parity had increased odds of overweight/obesity based on the Asian cutoff (AOR 1.11, 95% CI: 1.08–1.14), and both the 1–4 (AOR 1.13, 95% CI: 1.09–1.16) and ≥ 5 parity (AOR: 1.11, 95% CI: 1.07–1.16) had positive association with this outcome based on the WHO cutoff. Although women who were using hormonal contraceptives during the survey period had positive association with overweight/obesity as per the Asian cutoff (AOR: 1.05, 95% CI: 1.02–1.08), it had insignificant association as per the WHO cutoff (AOR: 0.99, 95% CI: 0.96–1.02). Marital status, religion, castes, education level, wealth status, place and region of residence also had significant relationships with overweight/obesity.

Discussion

Using a large nationally representative sample, this study shows that although underweight remains a significant public health issue (affecting roughly 1 in 5 women), overweight/obesity now affects a similar or greater proportion of women depending on which cutoffs are used (1 in 5 women according to WHO cutoffs vs 1 in 3 women according to Asian cutoffs). Although the Asian cutoffs identified a greater proportion of women as overweight/obese, the associated factors were similar. We observed increased prevalence and odds of underweight among younger, never-pregnant, non-users of hormonal contraceptive, unmarried, backward classes, less educated, and less wealthy women. Most factors that had positive association with the prevalence and odds of underweight, had inverse (i.e., negative, protective against, or were in opposite direction) association with overweight/obesity.

The positive association between age and body weight could be due to the fact that increasing age is a known associated factor of overweight as well as for other non-communicable diseases [23]. Furthermore, advancing age is correlated with number of parity, another associated factor for overweight/obesity [24]. Women usually gain weight during pregnancy, which could be sustained for a lifetime if weight loss does not occur in the post-partum period [13, 25]. Additionally, never-married women had higher odds of underweight, and ever-married women had higher odds of overweight/obesity as per both cutoffs. The greater odds among ever-married women might be due to gestational weight gain but could also be influenced by increasing socioeconomic status and related factors. Similar to earlier studies, women who reported that they were using hormonal contraceptives during the survey period had increased prevalence of overweight/obesity compared to women who were not using hormonal contraceptives [26, 27]. In addition to the weight gain associated with hormonal contraceptive use, women who use hormonal contraceptives are more likely to be older, have children, or be married [28, 29]. These factors might have synergistic effects on the body weights of hormonal contraceptive-using women.

Socioeconomic variables such as urban residence, higher education level, and wealth status had positive association with overweight/obesity per both cutoffs. In contrast, rural women were more likely to be underweight. Women with higher education level are more likely to have higher wealth status than less-educated women [30]. Previous research from India and other South Asian countries have observed similar relationships [16, 31, 32]. People with a higher SES in developing countries usually follow more sedentary lifestyles or less labor-intensive occupations, and consume more energy due to their greater purchasing ability [33, 34]. These characteristics could result in increased body weight among these individuals. The increased prevalence of underweight among women with lower SES could result from consuming fewer calories and less nutritious foods. People with a lower SES might not be able to afford adequate food for themselves and their families and may lack knowledge regarding nutritious foods [34]. Differences in socioeconomic, dietary, and lifestyle factors could contribute to the differences in weight categories between castes and religions. For instance, a large proportion of Hindu people in India are vegetarians, and they consume less calorigenic foods compared to non-vegetarians [35, 36].

Our findings have considerable public health implications for a populated country like India, where more than one-sixth of the total world population lives and about half of the women are within their reproductive age [21]. Furthermore, considering the population size, this sample represents more than one-twelfth of the total women in the world. The combined prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity was 56.2% as per the Asian cutoffs; in contrast, the WHO cutoffs found the combined prevalence as 43.5%. Lowering the cutoff reclassified a significant proportion of women as overweight/obese. However, due to higher health risks for Asian people at a lower BMI cutoff, these findings indicate that more than half of these women could be at an elevated risk of cardiovascular and reproductive health-related adverse consequences [22]. Moreover, programs targeting reduction of neonatal or childhood mortality may not be successful without addressing maternal nutrition issues, as maternal health is closely related to child health [10,11,12,13]. Although the prevalence of overweight/obesity categorized by the WHO-recommended cutoffs was lower than in high income countries, the prevalence of underweight was substantially higher than in wealthier countries [5, 6]. Among women who are at a greater risk of complications resulting from extreme BMIs, it is important to increase awareness to maintain a healthy weight; understanding the factors that are associated with higher prevalence or likelihood of both conditions are important in this context. All of these identified factors are also known correlates of body weights that have been established by a large number of earlier studies conducted in many LMICs including India [16, 18, 19, 31,32,33]. Our study reconfirmed the significance of these factors.

This study has several limitations. Since this dataset was cross-sectional, some observed factors might not be causally associated due to lack of evidence about temporal relationship. Some known associated factors including physical activity levels, dietary habits, nutritional factors, or other comorbid conditions were not adjusted due to limitations of the dataset. However, this study has several notable strengths. First, highly trained teams used standardized and validated instruments to obtain all measurements in NFHS-4. The survey had a large sample size and a high response rate. It covered rural and urban regions of all states. These findings may be generalizable to all women of reproductive age in India. To our knowledge, this is the first population-based study that reported prevalence and correlates of underweight and overweight/obesity among women of reproductive age in India as per two recommended cutoffs.

Conclusion

Our results show that a large proportion of reproductive-aged women belong to non-normal BMI categories in India, placing them at increased risks of complications resulting from underweight or overweight/obesity. As the associated factors are similar regardless of cutoffs, addressing factors associated with a higher prevalence of these ‘non-normal’ BMI categories is crucial not only to combating the overall noncommunicable disease burden, but also for improving maternal and child health conditions.

Availability of data and materials

Data is available upon request from the ICF International website (https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm). Dr. Kibria has full access to the data and takes responsibility for the accuracy of the data analysis.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CEBs:

-

Census enumeration blocks

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COR:

-

Crude odds ratio

- EA:

-

Enumeration area

- NFHS:

-

National Family and Health Survey

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PSU:

-

Primary sampling unit

- SC:

-

Scheduled castes

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status

- ST:

-

Scheduled tribes

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Zheng W, McLerran DF, Rolland B, Zhang X, Inoue M, Matsuo K, et al. Association between body-mass index and risk of death in more than 1 million Asians. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:719–29.

Berrington de Gonzalez A, Hartge P, Cerhan JR, Flint AJ, Hannan L, RJ MI, et al. Body-Mass Index and Mortality among 1.46 Million White Adults. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2211–9.

Ni Mhurchu C, Rodgers A, Pan WH, Gu DF, Woodward M. Asia Pacific cohort studies collaboration. Body mass index and cardiovascular disease in the Asia-Pacific region: an overview of 33 cohorts involving 310 000 participants. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33:751–8.

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19·2 million participants. Lancet. 2016;387:1377–96.

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;390:2627–42.

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766–81.

Lovejoy JC. The influence of sex hormones on obesity across the female life span. J Women's Health. 1998;7:1247–56.

Kanter R, Caballero B. Global gender disparities in obesity: a review. Adv Nutr. 2012;3:491–8.

Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1·9 million participants. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e1077–86.

Cresswell JA, Campbell OM, De Silva MJ, Filippi V. Effect of maternal obesity on neonatal death in sub-Saharan Africa: multivariable analysis of 27 national datasets. Lancet. 2012;380:1325–30.

Deshmukh VL, Jadhav M, Yelikar K. Impact of HIGH BMI on pregnancy: maternal and Foetal outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2016;66:192–7.

Patel A, Prakash AA, Das PK, Gupta S, Pusdekar YV, Hibberd PL. Maternal anemia and underweight as determinants of pregnancy outcomes: cohort study in eastern rural Maharashtra. India BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021623.

Bhavadharini B, Anjana RM, Deepa M, Jayashree G, Nrutya S, Shobana M, et al. Gestational weight gain and pregnancy outcomes in relation to body mass index in Asian Indian women. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2017;21:588–93.

Barroso CS, Roncancio A, Hinojosa MB, Reifsnider E. The association between early childhood overweight and maternal factors. Child Obes. 2012;8:449–54.

John C, Ichikawa T, Abdu H, Ocheke I, Diala U, Modise-Letsatsi V, et al. Maternal overweight/obesity characteristics and child anthropometric status in Jos. Niger Niger Med J. 2015;56:236.

Chowdhury MAB, Adnan MM, Hassan MZ. Trends, prevalence and risk factors of overweight and obesity among women of reproductive age in Bangladesh: a pooled analysis of five national cross-sectional surveys. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e018468.

Vaidya A, Pathak RP, Pandey MR. Prevalence of hypertension in Nepalese community triples in 25 years: a repeat cross-sectional study in rural Kathmandu. Indian Heart J. 2012;64:128–31.

Rai RK, Jaacks LM, Bromage S, Barik A, Fawzi WW, Chowdhury A. Prospective cohort study of overweight and obesity among rural Indian adults: sociodemographic predictors of prevalence, incidence and remission. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021363.

Kulkarni VS, Kulkarni VS, Gaiha R. “Double burden of malnutrition”: reexamining the coexistence of undernutrition and overweight among women in India. Int J Health Serv. 2017;47:108–33.

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), ICF International. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015–16: India. https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-fr339-dhs-final-reports.cfm. Accessed 12 Oct 2018.

Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos. Accessed 24 Dec 2017.

Expert WHO. Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363:157–63.

Reas DL, Nygård JF, Svensson E, Sørensen T, Sandanger I. Changes in body mass index by age, gender, and socio-economic status among a cohort of Norwegian men and women (1990–2001). BMC Public Health. 2007;7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-7-269.

Li W, Wang Y, Shen L, Song L, Li H, Liu B, et al. Association between parity and obesity patterns in a middle-aged and older Chinese population: a cross-sectional analysis in the Tongji-Dongfeng cohort study. Nutr Metab. 2016;13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-016-0133-7.

Kominiarek MA, Peaceman AM. Gestational weight gain. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:642–51.

Lopez LM, Edelman A, Chen M, Otterness C, Trussell J, Helmerhorst FM. Progestin-only contraceptives: effects on weight. In: the Cochrane collaboration, editor. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester, UK; 2013. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008815.pub3.

Pantoja M, Medeiros T, Baccarin MC, Morais SS, Bahamondes L, dos Santos Fernandes AM. Variations in body mass index of users of depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate as a contraceptive. Contraception. 2010;81:107–11.

Prusty RK. Use of contraceptives and unmet need for family planning among tribal women in India and selected hilly states. J Health Popul Nutr. 2014;32:342–55.

Haq I, Sakib S, Talukder A. Sociodemographic factors on contraceptive use among ever-married women of reproductive age: evidence from three demographic and health surveys in Bangladesh. Med Sci. 2017;5:31.

Bloomberg L, Meyers J, Braverman MT. The importance of social interaction: a new perspective on social epidemiology, social risk factors, and health. Health Educ Q. 1994;21:447–63.

Bishwajit G. Household wealth status and overweight and obesity among adult women in Bangladesh and Nepal: household wealth status and obesity among women. Obes Sci Pract. 2017;3:185–92.

Biswas T. Uddin MdJ, Mamun AA, Pervin S, P Garnett S. increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity in Bangladeshi women of reproductive age: findings from 2004 to 2014. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181080.

Bhurosy T, Jeewon R. Overweight and obesity epidemic in developing countries: a problem with diet, physical activity, or socioeconomic status? Sci World J. 2014;2014:1–7.

Lear SA, Teo K, Gasevic D, Zhang X, Poirier PP, Rangarajan S, et al. The association between ownership of common household devices and obesity and diabetes in high, middle and low income countries. CMAJ. 2014;186:258–66.

Joy EJ, Green R, Agrawal S, Aleksandrowicz L, Bowen L, Kinra S, et al. Dietary patterns and non-communicable disease risk in Indian adults: secondary analysis of Indian migration study data. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20:1963–72.

Kehoe SH, Krishnaveni GV, Veena SR, Guntupalli AM, Margetts BM, Fall CHD, et al. Diet patterns are associated with demographic factors and nutritional status in south Indian children: diet patterns of Indian children. Matern Child Nutr. 2014;10:145–58.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to ICF International, Rockville, Maryland, USA for the approval to use this dataset. The authors also acknowledge all survey staff and study participants for their valuable time and efforts. The NFHS-4 was administered under the stewardship of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), Government of India. The International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), Mumbai implemented the survey. The United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID), the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF), United Nations Populations Fund (UNFPA), the MacArthur Foundation, and the Government of India funded the survey. ICF International provided technical assistance.

Funding

Not received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept, Literature Search, and Statistical Analysis: GMAK and AS. Writing – first draft: GMAK, ZH, AS, and KS. Writing – review and editing: KS, ZH, and BD. Supervision: BD. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Boards of the International Institute for Population Science and ICF International provided the ethical approval. All respondents (if 18 years or older) or their legal guardian (if younger than 18 years) provided informed consent. We obtained electronic approval to use the data from ICF International, Rockville, Maryland, USA in October 2018.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Description of study variables. Fig. S1. Prevalence of different body mass index categories. (DOCX 171 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Al Kibria, G., Swasey, K., Hasan, M.Z. et al. Prevalence and factors associated with underweight, overweight and obesity among women of reproductive age in India. glob health res policy 4, 24 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-019-0117-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-019-0117-z