Abstract

Background

Recent advances in nanotechnology have offered new hope for cancer detection, prevention, and treatment. Nanomedicine, a term for the application of nanotechnology in medical and health fields, uses nanoparticles for several applications such as imaging, diagnostic, targeted cancer therapy, drug and gene delivery, tissue engineering, and theranostics.

Results

Here, we overview the current state-of-the-art of radiolabeled nanoparticles for molecular imaging and radionuclide therapy. Nanostructured radiopharmaceuticals of technetium-99m, copper-64, lutetium-177, and radium-223 are discussed within the scope of this review article.

Conclusion

Nanoradiopharmaceuticals may lead to better development of theranostics inspired by ingenious delivery and imaging systems. Cancer nano-theranostics have the potential to lead the way to more specific and individualized cancer treatment.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, there has been a significant and growing interest in the fields of nanoscience and nanotechnology (Hulla et al. 2015). Nanotechnology can be defined as the science and engineering concerned with the design, synthesis, characterization, and application of materials and devices at the nanometer scale (Saini et al. 2010). Also, nanotechnology is used in many technology and industry fields such as information technology (Chong 2004), homeland security (Reynolds and Hart 2004), transportation (Mathew et al. 2019), environmental science (Taran et al. 2021), energy (Abdin et al. 2013; Ahmadi et al. 2019), food science (Singh et al. 2017), and medicine (Mehta et al. 2008).

On the other hand, nanomedicine is defined as the application of nanotechnology to health according to the European Technology Platform on Nanomedicine. Here, nanomedicine exploits the improved and often novel physical, chemical, and biological properties of materials at the nanometric scale (Boisseau and Loubaton 2011). Thus, nanomedicine products are nanoparticles (NPs) that can be used for imaging (Padmanabhan et al. 2016), targeted cancer therapy (Xu et al. 2019), drug and gene delivery (Zhou et al. 2018), tissue engineering (Fathi-Achachelouei et al. 2019), and theranostics (Kucharczyk et al. 2019). NPs are particles with at least one dimension smaller than one micron (Buzea et al. 2007). Nanoparticular systems, ranging in size from a few nanometers such as micelles to several hundred nanometers, such as liposomes, can easily interact with biomolecules located on both the cell surface and inside (Boisseau and Loubaton 2011).

The nanometer-scale favors the drug delivery application since nanosized formulations have a larger surface to volume ratio than microsized formulations. For instance, less than 0.01% of the injected dose of drugs in the angstrom size typically accumulates in the target region, while the same value is approximately 1–5% for nanoparticles (Wolfram et al. 2015). Hence, the larger surface area of NPs may improve the efficacy of the therapies. Moreover, the distribution, targeting ability, and toxicity of NPs in the body are mediated by their shape and size. According to the literature, approximately 100 nm is the optimum size for NPs to avoid immediate clearance by the lymphatic system (Rizvi and Saleh 2018). However, NPs with a size of 100 nm result in restricted NP accumulation around tumor blood vessels and poor penetration into the tumor parenchyma (Zein et al. 2020; Moghimi et al. 2001). In contrast, NPs smaller than 10 nm are cleared by renal excretion and phagocytosis (Barua and Mitragotri 2014). Nanometer size is also important for passive targeting in cancer because of the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect due to the leaky vasculature of solid tumors and absence of lymphatic drainage (Bertrand et al. 2014; Farjadian et al. 2019).

Furthermore, the surface of NPs can be functionalized with small and larger molecules like biomolecules (e.g. peptides, aptamers, antibodies) via covalent bonds for specific and active targeting. In addition, the surface of NPs can be made more hydrophilic by coating with polymers such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) to reduce the opsonization (Rizvi and Saleh 2018). After intravenous (i.v.) administration, NPs are quickly opsonized and cleared by the macrophages (Yoo et al. 2010). Opsonization is the binding of the opsonins (serum proteins) to the surface of the NPs, which are recognized by the macrophage scavenger receptor and internalized (Li and Huang 2008). These macrophages are known as the reticuloendothelial system (RES), which consists of the liver and spleen, and is the first barrier that removes many NPs from circulation (Zein et al. 2020). Thereby, PEGylation is a strategy often used to increase the circulation times of NPs in the body while diminishing the RES uptake and favoring the target uptake.

The increasing number of publications per year index related to radiolabeled nanomaterials for biomedical applications corroborate the growing interest in the field (Fig. 1a). Tthe radiolabeling of nanomaterials has been performed using different radionuclides, with technetium-99m (99mTc), copper-64 (64Cu), lutetium-177 (177Lu) being the most popular for this application. However, other radionuclides like radium-223 (223Ra) and carbon-14 (14C) (Nallathamby et al. 2015; Soubaneh et al. 2020), gallium-68 (68Ga) (Biagiotti et al. 2019; Marenco et al. 2021), zirconium-89 (89Zr) (Chen et al. 2017, 2018), iodine-125 (125I) (Jeon et al. 2016; Tao et al. 2021), yttrium-90 (90Y) (Paik et al. 2015), gold-199 (199Au) (Zhao et al. 2016a), barium-131 (131Ba) (Falco Reissig et al. 2020) etc., have also been used for radioactive-labeling nanomaterials in radiopharmacy (Fig. 1b).

The design of functionalized radiolabeled nanomaterials with specific-target and imaging moieties, showing safety and high circulation times without metabolic degradation, is attractive for Nuclear Medicine, especially for theranostic applications. Theranostics combine diagnostic and therapeutic applications, which contribute to implementing individualized dosimetry-based treatment (Hosono 2010). In fact, the use of radiolabeled NPs has mainly been evaluated in cancer for molecular imaging (Bluemel et al. 2015; Surasi et al. 2015; Jin et al. 2017; Thakare et al. 2019; Du et al. 2017), radionuclide therapy alone (Cai et al. 2017; Cvjetinović et al. 2021), or combined with other therapies such as plasmonic photothermal (González-Ruíz et al. 2018; Mendoza-Nava et al. 2017), chemotherapy (Gibbens-Bandala et al. 2019), and immunotherapy (Pei et al. 2021a), as well as theranostics (Imlimthan et al. 2021). Most of these works use preclinical cancer models.

Molecular imaging combines in vivo imaging and molecular biology in order to identify or describe living biological processes at a cellular and molecular level using noninvasive procedures (Wu and Shu 2018). Positron- and gamma-emitting radiolabeled NPs are used for molecular imaging using positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), respectively. These nuclear imaging modalities (PET and SPECT) provide functional information. In addition, imaging studies with radiolabeled NPs usually combine PET and SPECT imaging with computed tomography (CT) to add anatomical information (Wong et al. 2017; Lee et al. 2017). In case the radiolabeled NP is a material with magnetic properties useful for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), then it can be used as a dual-modal (PET/MRI and SPECT/MRI) molecular imaging probe (Shi and Shen 2018; Gao et al. 2016). Also, MRI provides morphological and anatomical information. Some radiolabeled NPs can be used as three-modal imaging probes. For instance, they combine PET/MRI/fluorescence optical imaging (Thakare et al. 2019; Kim et al. 2018), and PET/MRI/photoacoustic tomography (Jin et al. 2017), adding valuable information. These imaging techniques are based on different basic physical principles. These techniqueshave certain advantages and disadvantages in terms of sensitivity and specificity to contrast agents, tissue contrast, spatial resolution, quantitation, and tissue penetration (Baetke et al. 2015).

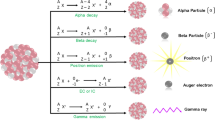

Nevertheless, to date, only a few NPs are clinically approved and used to detect sentinel lymph nodes by SPECT imaging after radiolabeling with 99mTc (Thakor et al. 2016). This review paper presents the state-of-the-art NPs labeled with 64Cu and 99mTc for PET and SPECT imaging, respectively, combined with CT, MRI, fluorescence optical imaging or photoacoustic tomography. Radionuclide therapy is a safe and effective approach to treat cancer by delivering ionizing radiation using radiopharmaceuticals that either bind preferentially to cancer cells or accumulate by physiological mechanisms (Sgouros et al. 2020). For therapeutic aims, the radiopharmaceuticals are formulated with radionuclides that emit Auger electrons, beta or alpha particles, releasing the ionizing radiation in the proximity of the target. Auger electrons have high linear energy transfer (LET) (4–26 keV/µm) and the shortest range (2–500 nm), limiting their application to treat single cancer cells once the radionuclide had crossed the cell membrane and reached the nucleus (Poty et al. 2018). In contrast, alpha particles are more effective for small neoplasms or micrometastases because of their highest LET (80 keV/µm) and short-range (50–100 µm) (Poty et al. 2018). Conversely, the beta particles are more effective in treating medium to large tumors owing to their longest particle range (0.5–12 mm) and LET (0.2 keV/µm) (Poty et al. 2018). We also present the state-of-the-art of NPs labeled with the beta emitter 177Lu and the alpha emitter 223Ra for radionuclide therapy (177Lu, 223Ra) and theranostics (177Lu). In addition, the chemical and nuclear properties of the selected radionuclides, radiolabeling of NPs, the EPR effect, and other strategies to improve the efficacy of NPs and their toxicity are overviewed in this review paper. Liver radioembolization using microspheres labeled with the beta emitters 90Y or holmium-166 (166Ho) is one of the most successful clinical applications using radiolabeled microparticles (D’Abadie et al. 2021). This application is also described in the context of the present review.

Nanomaterials

Nanomaterials are materials with structural components smaller than one micrometer in at least one dimension (Buzea et al. 2007), which represent a vast class of compounds (Fig. 2). They can be classified into three major categories: (1) inorganic nanomaterials, which comprise noble metals, magnetic metals, quantum dots, and non-metals, (2) organic nanomaterials, which consist of polymers and lipids; and (3) carbon nanomaterials. Inorganic nanomaterials are a multifaceted class that comprises two groups (1) metallic and (2) non-metallic. The development of metallic NPs is of significant interest due to their unique and relevant characteristics, including their optical activity, electrical and magnetic properties, mechanical stability, and large surface area (Khan et al. 2019).

Examples of nanomaterials available or under research worldwide, representing the main forms/structures, including polymeric nanoparticles, metal nanoparticles (gold and silver mainly), liposomes, mesoporous silica, and graphene (and graphene derivatives, like graphene quantum dots and graphene oxide)

The non-metallic nanomaterials group consists mainly of mesoporous silica, formed by groups of silicon oxide organized in hexagonal, cubic, or lamellar structures (Cong et al. 2018). According to IUPAC (International Union of Pure and-Applied Chemistry), its pores should have a diameter of 2–50 nm (Costa and Paranhos 2020). The interest for this material is related to its distinct characteristics, such as porous structures with adjustable volume and diameter, large surface area, and high density of silanol on the surface, which allows the nanomaterial to function (Vallet-Regí et al. 2007; Gisbert-Garzarán et al. 2020). This nanomaterial has several applications, such as targeting drugs and genes (Aquib et al. 2019; Kesse et al. 2019), antibacterial treatment (Bernardos et al. 2019), and bone tissue regeneration (Kanniyappan et al. 2021).

Mesoporous magnetic silica has a magnetic core comprising iron oxide bound to silica (Fe3O4–SiO2) or hollow mesoporous silica NPs (MSNs) (Wu et al. 2020a). However, the use of hollow MSNs, with a large central hole combined with an external mesoporous silica shell, offers an additional advantage due to the higher loading capacity. They have greater storage capacity and can remain in the tissues for a limited period without causing damage. At the same time, magnetic MSNs allow the targeting of drugs, genes, and imaging agents through an external magnetic field (Kesse et al. 2019). Superparamagnetic materials, having a single-domain character, which causes a phenomenon called superparamagnetism. These kinds of materials do not retain any residual magnetization after removing the external magnetic field, thus preventing possible agglomeration of nanoparticles in the bloodstream and the formation of possible embolism (Lu et al. 2007).

Organic nanomaterials are divided into two major categories (1) organic lipid nanomaterials and (2) organic polymeric nanomaterials. These nanomaterials are mainly used to develop nanoplatforms for targeting drugs, genes, and imaging agents. The structures of liposomes can be obtained from lipid compounds, both of which have the advantage of biocompatibility and easy encapsulation of substances. Liposomes consist of a bilayer of amphiphilic lipids, which have proven to be efficient carriers for targeting various substances since they possess amphipathic domains around an aqueous nucleus and enable the rapid integration of molecules with different physicochemical properties (Penoy et al. 2020). Therefore, hydrophilic substances are encapsulated in the core of the nanostructure, and lipophilic substances are intercalated in the lipid bilayer (Romero-Arrieta et al. 2020). Highly toxic or low bioavailability drugs benefit from the stabilizing nature and improved biodistribution of liposomes and micelles in circulation. Organic lipid nanomaterials and organic polymeric nanomaterials are often synthesized using polymers or coated to avoid recognition by cells and components in the reticuloendothelial system (Moghimi and Reviews 1998; Bobo et al. 2016; Maiolo et al. 2015).

The group of polymeric organic nanomaterials can be divided into two categories: (1) biodegradable polymers and (2) non-biodegradable polymers. They can be obtained in different morphologies of nanosystems, such as nanospheres (it has a polymeric matrix nucleus), nanocapsules (composed of a polymeric shell containing an oily or aqueous nucleus), and dendrimers (formed by a branching nucleus). Additionally, polymeric nanosystems are capable of releasing drugs in a controlled, and sustained manner in the body through three mechanisms: (1) the active molecules cross the polymer barrier by diffusion; (2) erosion of the polymeric material, and (3) penetration of solvent/swelling of the system (Martins et al. 2018). Among the polymers, biodegradable polymers are the most interesting and used because of their intrinsic properties, such as biodegradability (Jana et al. 2020), biocompatibility (Biswas et al. 2020), colloidal stability (García et al. 2020), non-inflammatory (García-Valdivia et al. 2020), and non-immunogenic nature (Andorko et al. 2016), including their small size, functionalizable surface, and good solubility (Carvalho and Conte Junior 2020). Biodegradable polymers are degraded in vivo, preferably by hydrolysis or enzymatic breakdown, producing biocompatible and non-toxic by-products eliminated by normal metabolic pathways (Mir et al. 2017).

Composite nanomaterials combine a number of properties of all the previously listed groups. These are often systems composed of metallic or metallic-oxide materials coated with a silica or polymer corona which can be further chemically modified (Novy et al. 2020). The motivation for preparing such a composite nano-construction is the combination of the most favorable properties of the types mentioned above of nanomaterials to be used as multimodal theranostic nanoprobes. By combining it with various novel nanoparticle-based activatable probes, molecular imaging technologies can provide a feasible approach to visualize tumor-associated microenvironment parameters noninvasively and realize the accurate treatment of tumors.

Furthermore, graphene and its derivatives like graphene quantum dots and graphene oxide are carbon-based nanomaterials. Graphene is a crystalline material and a two-dimensional nanostructure with sp2 hybridized carbon atoms that form a hexagonal honeycomb structure (Magne et al. 2021a). The graphene surface can interact with other molecules through physical adsorption mechanisms (π-π interactions), or chemical interaction (covalent bonding). For this, the structure of graphene is previously modified through the introduction of defects or functional groups such as carboxyl, carbonyl and amino (Felix et al. 2021). Several biomedical applications of graphene and its derivatives have been reported so far, which were recently reviewed by our group (Magne et al. 2021a).

Nanoparticles can achieve a diagnostic and, at the same time, therapeutic effect depending on the type of radionuclide and/or chemical modification enabling controlled drug release. The chemical behavior of nanoparticles labeling depends on the category mentioned above (i–iiii). In general, labeling of the prepared nanoparticles might be performed (a) by surface sorption of the radionuclide to the surface of the nanoparticle directly, (b) intrinsic encapsulation of the radionuclide into the core of the nanoparticle during the synthesis, (c) chelation of radionuclide by ligands (mostly polydentate, e.g., DTPA (Diethylenetriamine pentaacetate), DOTA (1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid), and NOTA (1,4,7-triazacyclononane-N,N′,N″-trisacetic acid) derived analogs) directly attached or linker spaced on the surface of the nanoparticle.

Parameters like particle size, specific surface area, contact time, and temperature play an important role. Moreover, the liquid phase composition, such as pH, the concentration of radionuclide ions, ionic strength, the presence of complexation ligands, etc., should be considered (Suchánková et al. 2020a). Same conditions should be followed during intrinsic labeling, and also reaction conditions of nanoparticles preparation must be considered.

The EPR effect and other strategies to improve the efficacy of nanoparticles

The natural accumulation of NPs after i.v. administration is in the liver, which can negatively affect their targeting. Suppression of this effect leads to a better uptake in targeted tissues as well as a decrease of radiation burden to surrounding tissues. Proper targeting of NPs can generally be achieved either by binding system stabilizers/targeting vectors to the surface of the NPs (antibodies, polymers, peptides, etc.) or by using the EPR effect (Ballinger 2018; Pratt et al. 2016; Sharma et al. 2021).

The EPR effect is a phenomenon (Fig. 3), which occurs in solid tumors sites due to their anatomical and pathophysiological differences from normal tissues. The exacerbated angiogenesis promoted by the uncontrolled cell proliferation during cancer leads to high vascular density in solid tumors. The new vasculature produced during this angiogenesis process has large gaps between endothelial cells, which cause the extravasation of nanoparticles into the lumen of the tumor (permeation effect). Also, the new vasculature grows in a distorted form, causing a deficiency in the lymphatic drainage, leading to permanent retention of the nanoparticle in the tumor (retention effect). Although the EPR effect is the most well-known effect related to nanoparticle efficacy, it is not the only process involved in the mechanism (Shi et al. 2020; Yhee et al. 2013). Recently, it was detected that immune cells in the tumor microenvironment play important roles in accumulation, retention, and intratumoral distribution. For instance, Korangath et al. (Korangath et al. 2020) showed that NPs were retained in the tumor by association with dendritic cells, neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages and not just by the EPR effect.

Also, the use of active targeting is a good strategy to improve tumor accumulation, preventing nanoparticle dispersion on non-primary targets. In this direction, the use of ligands like fragments of antibodies, monoclonal antibodies, aptamers, and peptides represent an interesting approach.

Radiolabeled nanomaterials for molecular imaging

99m Tc-based radiolabeled nanomaterials

99mTc has a half-life of 6 h and emits gamma rays of 140.5 keV. 99mTc is available worldwide due to its cheap production using the 99Mo/99mTc radionuclide generator. In the generator system, 99Mo transforms to 99mTc at a rate of 87% and to 99Tc at a rate of 13% by beta decay with 740–780 keV energy. Tc has eight oxidation states from − 1 to + 7, being + 7 and + 4 the most stable valency. Its + 7 valence state (99mTcO4−) does not combine directly with other compounds. Since 99mTcO4− is chemically nonreactive and cannot label any compound by direct addition, radionuclide reduction to lower oxidation states is required. The reduction is obtained by various reducing agents include stannous chloride, stannous citrate, stannous tartrate, sodium borohydride, ferrous sulfate, etc. (Saptiama et al. 2016; Hou et al. 2007; Hasan and Prelas 2020).

The use of 99mTc has continued to evolve, especially with modern gamma cameras with advanced electronics and computing systems, revolutionizing nuclear medicine procedures. This development process continued until the first ready-to-use lyophilized kit for radiolabeling with 99mTc in the 1970s. Many new radiopharmaceuticals have been prepared with the discovery of very easy-to-use defined as shake and bake kits (Saleh 2011).

The kits are optimized to ensure that the desired complex has a high labeling yield. Several factors have influenced the labeling yield and the stability of the complex, such as the amount of reducing agent and ligand, pH, and temperature. The chemical groups suitable for direct radiolabeling by chelating technetium radionuclide are –OH, –COOH, –C=O, –PO4, –P2O7-, –NH2, –SOOH, –SOONH, –SOONH2, –OCH3. By using these chemical groups, radiolabeling can be done directly with 99mTc and through different chelate groups. In this context, the chelators frequently used with 99mTc are DOTA and DTPA of small molecules, colloids, and polymeric NPs. At the same time, the chelators that are frequently used with 99mTc labeled lipid-based NPs (such as; micelles, liposomes, solid LNPs) are HMPAO (D,L-hexamethylene-propyleneamine oxime).

To date, a few 99mTc-labeled NPs, mainly colloids, are clinically approved (Table 1). On the other hand, iron oxide NPs, oligomeric NPs, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), micelles, liposomes, solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs), MSNs have been 99mTc-labeled with/without chelate agents and evaluated in different preclinical cancer models as shown in Table 2.

64 Cu-based radiolabeled nanomaterials

Among the Cu radioisotopes, 64Cu is the most studied for biomedical applications using PET due to its attractive nuclear qualities. It decays by electron capture (41%, 1346 keV), positron (19%; 657 keV) and beta (40%; 578.7 keV) emissions, with an average tissue penetration of 0.7 and 0.95 mm for positron and beta particles, respectively (Ahmedova et al. 2018). Its relatively long half-life of 12.7 h allows for shipping to distant centers and for longer in vivo imaging studies compared to the well-established PET radionuclides: fluor-18 (109.7 min), gallium-68 (67.7 min), and carbon-11 (20.4 min). The low positron energy of 64Cu is closer to the positron energy of fluor-18 (634 keV), which favors image resolution (Conti and Eriksson 2016). Besides, the beta particles and Auger electrons emitted from the electron capture decay are useful for radionuclide therapy. In particular, the Auger electrons have a very low average energy (2 keV) and average tissue penetration (∼126 nm), resulting in high LET radiation that is potentially killing cancer cells (McMillan et al. 2015). Additionally, 64Cu can be produced in reactors and cyclotrons. The most common method is currently through proton irradiation of enriched nickel-64 solid target [64Ni(p,n)64Cu] in small medical cyclotrons, achieving the highest yields in the proton energy range of 10–15 MeV and enough high purity product (Synowiecki et al. 2018). In nuclear reactors, 64Cu can be produced by 63Cu(n,γ)64Cu and 64Zn(n,p)64Cu reactions using thermal and fast neutrons, respectively, with correspondingly low and high specific activities (Niccoli Asabella et al. 2014). However, the use of the high-specific activity 64Zn(n,p)64Cu reaction is limited because of the co-production of the zinc-65 radioisotope with a half-life of 245 days (Shokeen and Anderson 2009).

Cu’s most common oxidation states are 1+ and 2+, where ionic radius are 77 and 73 pm, respectively. Cu+ forms complexes without any crystal-field stabilization energy are not recommended for incorporation into radiopharmaceuticals due to insufficient kinetic stability. At the same time, Cu2+ is the best option for radiopharmaceutical applications owing to less labile toward ligand exchange by the presence of some crystal-field stabilization energy (Wadas et al. 2007). Moreover, Cu+ coordination compounds have been reported by complexation with N/N-, and phosphine-donor ligands, whereas Cu2+ coordination compounds are formed by complexation with N–, O– and S–, N– and O–, N– and S–, N/N–, and S/S– donor ligands (Krasnovskaya et al. 2020).

64Cu-labeled NPs are promising for cancer imaging by PET in combination or not with MRI or optical imaging. 64Cu-chelate complexation, chelate-free conjugation, and neutron activation are the main approaches used for 64Cu radiolabeling of NPs so far. DOTA, NOTA, NODAGA (1,4,7-triazacyclononane, 1-glutaric acid-4,7-diacetic acid) and 4-DEAP-ATSC (diacetyl 4,4′-bis(3-(N,N-diethylamino)propyl)thiosemicarbazone) have been the most used chelates for radiolabeling NPs. The best yields (> 95%) were obtained using NOTA/NODAGA chelates, performing the 64Cu-chelate complexation at the last step of the radiopharmaceutical preparation, except for ultra-pH sensitive (UPS) polymer (Huang et al. 2020) and micelles (Paiva et al. 2020) NPs. Conversely, several NPs have been 64Cu-labeled by chelate-free conjugation method with yields between 75 and 97% after reacting at 25–37 °C for 10–60 min and pH 5.5–7 (Jin et al. 2017; Madru et al. 2018; Xu et al. 2018; He et al. 2021). In particular, the copper sulfide ([64Cu]CuS) NPs were prepared with > 98% yield by doping CuS at pH 9 and heating at 65–90 °C for 15 min before functionalization for specific tumor targeting (Cui et al. 2018; Cai et al. 2018). Additionally, neutron activation is another method used for 64Cu radiolabeling NPs, delivering a radio-nanoprobe with good stability for cancer-targeted, controlled drug delivery and PET imaging (Oliveira Freitas et al. 2017).

Liposomes, lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), lipid nanodiscs (LND), micelles, UPS polymers, carbon quantum dots (CQDs), polyglucose nanoparticles (Macrin), melanin, gadolinium nanoparticles (AGuIX), silicon, silica gadolinium nanoparticles (SiGdNPs), iron-gallic acid coordination nanoparticles (Fe-GA-CPNs), superparamagnetic manganese ferrite (MnFe2O4), and CuS nanoparticles have been 64Cu-labeled and evaluated as PET tracers in different preclinical cancer models as shown by Table 3. Also, it has been shown that functionalization of these 64Cu-labeled NPs with peptides, programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) antibody, or anti-PSMA site-specific cysteine-diabody (cys-DB) enhanced tumor uptake. In particular, the radiolabeled Fe-GA-CPNs (Jin et al. 2017), MnFe2O4 (Shi and Shen 2018), SiGdNP (Tran et al. 2018), and AGuIX (Thakare et al. 2019) exhibited favorable outcomes for PET/MRI dual imaging of tumors. Among them, the 64Cu-labeled Fe-GA CPNs after surface modification with the hydrophilic polymer PEG exhibited much more efficient passive tumor accumulation (EPR effect) upon intravenous administration into tumor-bearing mice (Jin et al. 2017). Moreover, the introduction of the near-infrared heptamethine cyanine dye IR783 allowed obtaining nanorradiopharmaceuticals for PET/MRI/optical imaging (Thakare et al. 2019). Furthermore, doxorubicin (DOX)-loaded 64Cu-labeled NPs showed favorable results for chemotherapy and PET imaging (Du et al. 2017; Wong et al. 2017). Thereby, the preclinical reports of 64Cu-labeled NPs are mainly focused on their use for treatment planning and monitoring the therapeutic responses by PET imaging.

Additionally, clinical PET images with 64Cu-labeled NPs were also reported, for instance, to quantify the variability of the EPR effect of NPs in relation to treatment response in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. The authors used the [64Cu]Cu-MM-302 nanoprobe prepared by 64Cu-chelate (4-DEAP-ATSC) complexation before reaction with MM-302 (HER2-targeted PEGylated liposomal DOX) NPs. [64Cu]Cu-MM-302 was safe and stable in patients within the image acquisition time frame. PET/CT imaging showed significant tumor accumulation in bone and brain lesions with high [64Cu]Cu-MM-302 deposition at 24–48 h and significant background uptake in the liver and spleen as well (Lee et al. 2017).

Beyond PET imaging, however, there is a lack of reports evaluating the potential of 64Cu-labeled NPs for radionuclide therapy, taking into account the beta particles and Auger electrons emitted by 64Cu. We only found [64Cu]Cu-PEG-melanin NPs evaluated for PET imaging and radionuclide therapy in the reviewed period with promissory results. The authors reached radiolabeled melanin with good stability using the chelate-free conjugation method due to the inherent chelating ability of melanin to [64Cu]Cu2+ ion. PET images with [64Cu]Cu-PEG-melanin exhibited the highest tumor uptake at 4 and 8 h after tail vein injection in epidermoid carcinoma tumor-bearing mice. Tumor growth was significantly decreased compared to control groups at one week after a single intravenous injection of [64Cu]Cu-PEG-melanin (~ 55.5 MBq) when tumors reached diameters of 5–8 mm, without radioactive cytotoxicity to normal tissues (Zhou et al. 2020). Therefore, we encourage to continue assessing the efficiency of 64Cu-labeled NPs for radionuclide therapy as theranostic agents, also considering nanomaterials’ favorable properties for enhancing targeted radionuclide delivery and retention into tumors.

Radiolabeled nanomaterials for radionuclide therapy

177 Lu-based radiolabeled nanomaterials

Among the artificial radioisotopes, 177Lu is the most known and routinely used in nuclear medicine. 177Lu is a theranostic radioisotope because of its beta and gamma decay. Its low-energy beta particles (mean energy of 134 keV; maximum energy of 498 keV (79%)) have a mean range of 0.7 mm and a maximum of 2.1 mm in soft tissue (Ahmadzadehfar et al. 2020). Furthermore, its emitted photons of 113 keV (6.2%) and 208 keV (10.4%) are useful for 177Lu SPECT dosimetry (Müller et al. 2017; Alnaaimi et al. 2021). Moreover, 177Lu has a half-life of 6.65 days, which is suitable for radionuclide therapy. On the other hand, 177Lu is mainly produced in nuclear reactors with high specific activity through neutron irradiation of either enriched 176Lu or 176Yb nuclides using lutetium oxide (Lu2O3) or ytterbium oxide (Yb2O3) as target material (Talip et al. 2020).

Lu forms complexes with organic ligands of high coordination numbers (6, 7, 8, and 9). DOTA is the macrocyclic ligand most used for [177Lu]Lu3+ complexation because of its high stability constant (Banerjee et al. 2015). [177Lu]Lu3+ complexes formation with macrocyclic ligands is very slow when low ligand concentrations are employed. However, at high pH (> 6), insoluble lanthanide hydroxides are formed (Banerjee et al. 2015). Therefore, heating (95–100 °C for 30–40 min) and pH (4.5–6) are critical variables to achieve near quantitative labeling yields of 177Lu-labeled peptides (Sharifi et al. 2018; Jowanaridhi and Sriwiang 2019).

177Lu-labeled NPs have improved cancer treatment outcomes in preclinical settings by enhancing the radionuclide delivery in tumors. Besides, the use of these labeled NPs in combination or not with other therapies such as chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or plasmonic–photothermal therapy is a unique nanoprobe assessed in preclinical cancer models (González-Ruíz et al. 2018; Gibbens-Bandala et al. 2019; Imlimthan et al. 2021; Pei et al. 2021b). Most of these NPs were radiolabeled by chelate complexation in the last step of the pharmaceutical preparation. Also, the principal conditions for this final step are a narrow range of temperatures (37–95 °C), labeling times (20–60 min), and pH values between 4 and 5 (Tao et al. 2021; Mendoza-Nava et al. 2017; Gibbens-Bandala et al. 2019; Pei et al. 2021b; Vats et al. 2018; Cytryniak et al. 2020). The best radiochemical yields (> 95%) were obtained by 177Lu-DOTA complexation at the conditions: pH 5 and 30 min @ 90–95 °C (Mendoza-Nava et al. 2017; Cytryniak et al. 2020).

Some studies reported the 177Lu-DOTA complexation previous to NPs functionalization (Cai et al. 2017; Imlimthan et al. 2021; González-Ruíz et al. 2017). In other cases, radiolabeling by neutron activation of NPs before functionalization (Ancira-Cortez et al. 2020, 2021) and radiolabeling without chelate complexation have been used (Cvjetinović et al. 2021; Ognjanović et al. 2019; Gaikwad et al. 2021). In addition, it was demonstrated that the radiolabeling without chelate complexation approach delivered the 177Lu-labeled NPs in high yields (> 98%) after the incubation of these NPs at room temperature for 30 min at pH 5–6. Also, the possible formation of a complex between [177Lu]Lu3+ and negatively charged carboxylate, hydroxyl and phosphate groups available on coated nanoparticles was proposed as a potential interaction mechanism (Cvjetinović et al. 2021; Ognjanović et al. 2019). In addition, both 177Lu radiolabeling via a chelator and direct labeling provided 177Lu-labeled NPs with good stability (> 95%) after 24 h (González-Ruíz et al. 2017), 72 h (Cvjetinović et al. 2021), and 96 h (Imlimthan et al. 2021; Ognjanović et al. 2019) of incubation in human serum at 37 °C. 177Lu incorporation by replacing a tracer quantity of Eu3+ in the EuDPA complex was another radiolabeling method reported (Viana et al. 2020). However, with this approach long reaction times (5 h) and several purification steps are necessary.

Dendrimers (DN), lipidic cubic-phase nanoparticles (cubosomes), chitosan (CH), liposomes, carbon nanospheres (CNS), nanoscale metal–organic frameworks (nMOFs), cellulose nanocrystals (CNC), gold nanoclusters (AuNCs), rare sesquioxides (Lu2O3), and AuNPs have been 177Lu-labeled and evaluated for cancer therapy in different preclinical cancer models as shown by Table 4. Most of them were functionalized with peptides, aptamers, antibodies, glucose, or human serum albumin (HSA) protein for targeted radionuclide therapy. Also, some NPs have been used for the encapsulating of paclitaxel (PTX), doxorubicin (DOX), and vemurafenib (V) to combine chemotherapy and radionuclide therapy in the same nanoprobe. Unfortunately, reports about their clinical application in patients have not been found yet, to the best of our knowledge.

Most of the 177Lu-labeled NPs have been prepared using gold nanoparticles. Z. Cai et al. (2017) prepared [177Lu]Lu-AuNPs-PEG-Trastuzumab nanoconjugate for studying its therapeutic effects in breast cancer by inhibiting the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) (Du et al. 2017). In this study, modified AuNPs with PEG linked to DOTA chelate (for radiolabeling) or to trastuzumab (an antibody that inhibits HER2 signaling pathways) were prepared. [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-PEG3k-OPSS was first prepared and then incubated with trastuzumab-PEG5k-OPSS and AuNPs to get the final nanoconjugate. [177Lu]Lu-AuNPs-PEG-Trastuzumab was more effective than [177Lu]Lu-AuNPs (without target functionalization), provoking a decrease in the clonogenic cell survival. As well as an inhibition of the tumor growth was observed after intratumoral injection (3 MBq) in mice bearing HER2-positive tumor xenograft when tumors reached 5–8 mm in diameter (Cai et al. 2017). Moreover, González-Ruíz et al. (2017, 2018) developed the 177Lu-labeled nanosystem by conjugating AuNPs with the NLS (nuclear localization sequence)—RGD (Arg-Gly-Asp) peptide and an aptamer. The final nanomaterial was prepared to target both α(v)β(3) integrin, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) overexpressed in the tumor neovasculature. First, the radiolabeled DOTA-GGC peptide is carried out, and then the coupling to AuNPs-NLS-RGD-Aptamer, obtaining the [177Lu]Lu-AuNPs-NLS-RGD-Aptamer NPs (29.99 ± 1.90 nm) (González-Ruíz et al. 2017). [177Lu]Lu-AuNPs-NLS-RGD-Aptamer decreased cell viability and completely inhibited angiogenesis. Besides, [177Lu]Lu-AuNPs-NLS-RGD-Aptamer inhibited tumor progression in mice with glioma tumors (size 0.05 ± 0.01 g) after intratumoral injection (2 MBq) and combined with laser irradiation (Fig. 4) (González-Ruíz et al. 2018). Despite those favorable therapeutic results reported for [177Lu]Lu-AuNPs-PEG-Trastuzumab and [177Lu]Lu-AuNPs-NLS-RGD-Aptamer, it could be interesting if the authors reproduce the in vivo studies using intravenous injection of the nano-radiopharmaceuticals to be closer to a possible clinical application.

Schematic representation of [177Lu]Lu-AuNPs-NLS-RGD-Aptamer nano-radiopharmaceutical. X-ray images (X-Treme/preclinical equipment) of mice with U87MG tumors under thermotherapy (AuNPs-NLS-RGD-Aptamer under laser irradiation), targeted radiotherapy ([177Lu]Lu-AuNPs-NLS-RGD-Aptamer), and thermotherapy plus radiotherapy ([177Lu]Lu-AuNPs-NLS-RGD-Aptamer under laser irradiation) treatments at 96 h after the last injection (at 25 days of treatment) (González-Ruíz et al. 2018, 2017)

Additionally, Mendoza-Nava et al. (2017) reported a hybrid nanosystem combining AuNPs and DN that also exhibited properties suitable for radionuclide therapy, optical imaging, and plasmonic–photothermal therapy under laser irradiation when the nanosystem is internalized in breast cancer cells. This nanoprobe ([177Lu]Lu-DNAuNPs-folate-bombesin) was prepared by conjugating [177Lu]Lu-DN to folate and bombesin peptides with AuNPs in the dendritic cavity to target both gastrin-releasing peptide receptors (GRPr) and folate receptors (FR), respectively. Cell viability assays showed that [177Lu]Lu-DNAuNPs-folate-bombesin is about four times more lethal than [177Lu]Lu-DNAuNPs, without bombesin (targets GRPr) and folate (targets FR) functionalization (Mendoza-Nava et al. 2017). This result evidences the potential effect of targeted radionuclide therapy.

Different types of NPs (AuNCs, and nMOFs) have been radiolabeled using chelates other than DOTA for 177Lu complexation with high radiolabeling stability. Pei et al. (2021a; b) studied the efficiency of radiolabeled glutathione (GSH) modified AuNCs (~ 2.5 nm) by chelation between 177Lu and GSH in the last step of the radiopharmaceutical preparation. To evaluate the therapeutic effect, [177Lu]Lu@AuNCs was intratumoral injected (2.8 MBq) when the volume of tumors reached ~ 75mm3. It effectively eliminated primary tumors and suppressed distant tumors’ growth when combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors, using the anti-programmed death-ligand 1 (αPD-L1), in mice bearing with breast or colon tumors. The radiolabeled AuNCs showed low physiological toxicity, distributing only in tumors and bladder after intratumoral injection. It was also demonstrated that the combination of radionuclide therapy ([177Lu]Lu@AUNCs) and immunotherapy (αPD-L1) significantly suppress the growth of spontaneously metastatic tumors and lengthen the survival time of the transgenic mice (Pei et al. 2021b). On the other hand, Tao et al. (2021) studied the radiolabeled PEG modified zirconium-based nMOFs (PCN-224) (~ 140 nm) by chelation between 177Lu and porphyrin structure, also in the last step of the radiopharmaceutical preparation. [177Lu]Lu-PCN-PEG exhibited high uptake in liver, spleen, kidneys, and tumor at 24 h after intravenous administration in breast tumor-bearing mice. Moreover, [177Lu]Lu-PCN-PEG reached high tumor accumulation after intravenous injection (5.55 MBq), resulting in significant inhibition of tumor growth and prolonged survival time without inducing any perceptible toxicity to the treated mice (Tao et al. 2021). Thus, neither [177Lu]Lu@AuNCs nor [177Lu]Lu-PCN-PEG were functionalized for binding to a specific target in tumors. However, they enhanced radionuclide therapy outcomes highlighting the favorable properties of NPs due to the EPR effect.

Conversely, Cvjetinović et al. (2021) demonstrated that 177Lu-labeled glucose-modified liposomes (97.3 ± 4.1 nm) exhibited significantly better tumor uptake and prolonged retention than 177Lu-labeled non-glucose liposomes (84.9 ± 3.6 nm) after intravenous injection into colon tumor-bearing mice. Hence, the authors concluded that the effect of solely passive EPR on the liposomal accumulation in tumor tissue is relatively low, while the functionalization with glucose enhanced the accumulation by glucose transporters and subsequent endocytosis (Cvjetinović et al. 2021). Therefore, the passive targeting of NPs in cancer by the EPR effect may not be enough in some cases for an efficient tumor accumulation. Thereby, the surface functionalization of NPs with specif-target moieties may overcome the previous limitation.

On the other hand, Chakravarty et al. (2020) reported the synthesis and evaluation of intrinsically radiolabeled [177Lu]Lu2O3 NPs entrapped in a protein scaffold ([177Lu]Lu2O3-HSA) through an HSA-mediated biomineralization process. [177Lu]Lu2O3-HSA nanocomposite (4.1 ± 1.2 nm) was rapidly and highly accumulated in melanoma tumors after intravenous injection with significant retention up to 7 days. Also, [177Lu]Lu2O3-HSA nanocomposite greatly retarded tumor growth on a one-time intravenous administration dose (37 MBq) without degenerating liver and kidney. Besides, biochemical and hematological parameters were unaffected, and no behavioral or phenotype changes were observed (Chakravarty et al. 2020).

Finally, Imlimthan et al. (2021) recently described a complete study about the theranostic potential of 177Lu-labeled CNC loaded with vemurafenib, a clinically approved tyrosine kinase inhibitor, using a murine model of metastatic lung melanoma. For preparing the [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V nanoparticles, CNC was radiolabeled by 177Lu-DOTA complexation, followed by drug loading in a one-pot reaction. [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V (9–14 nm width; 136–158 nm length) showed high retention in the metastatic lung up to 72 h post intravenous injection as well as high uptake in spleen and liver. The survival studies demonstrated its therapeutic potential for treating pulmonary metastatic melanoma through the synergist result of V chemotherapy and 177Lu radiotherapy. The therapeutic effects of [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V (2 MBq of 177Lu and 3.5 mg.kg−1 of V) were evaluated after the intravenous administration of the nanosystem, after 14 days of tumor inoculation, followed by a second round of treatment ten days later. Mice treated with [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs displayed the longest median survival time of 27 days after treatment, followed by cohorts treated with the [177Lu]Lu-CNC (17 days), free V (13 days), and vehicle (12 days) without observing acute toxicity (Imlimthan et al. 2021). Studies like this are fundamental before a clinical translation.

223 Ra-based radiolabeled nanomaterials/micromaterials

223Ra (11.4 d) is a member of the natural Uranium-235 (235U) decay chain and was discovered by T. Godlewski as a successive product of Actinium (Ac) decay and identified it as AcX analogically to the previously reported ThX (224Ra) (Godlewski 1839, 1905). Artificial preparation of 223Ra was performed by neutron irradiation of 226Ra (1600 y), leading to 227Ra (42 min) that decays to 227Ac (21.7 y) a mother nuclide of 227Th (18.7 d) and finally the 223Ra (Peterson et al. 1949). Thus the 223Ra generator based on 227Ac can be constructed (Guseva et al. 2004).

The EMA and FDA approved the first new-era clinical use of 223Ra for the therapy of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (MCRPC). This was the first approved pharmaceutical based on an alpha emitter on the market. However, its use is quite limited due to its self-targeting, mainly to bone tissues mimicking the calcium metabolism (Pharmacopoeia 2014). Attempts to prepare a chelator or other binding moiety for Ra and to label advanced targeting molecules like peptides or antibodies are still challenging the scientific community since the coordination chemistry of radium was not the subject of investigation for decades. Relevant studies appeared just recently employing EDTA (2,2′,2″,2‴-(Ethane-1,2-diyldinitrilo)tetraacetic acid or ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid), macrocyclic ligands, or polyanionic molecules like polyoxopalladates or even liposomes (Henriksen et al. 2002, 2004; Matyskin et al. 2017; Gott et al. 2019; Abou et al. 2021). Completely different approach in targeted alpha therapy that employs preferentially inorganic nanomaterials was proposed to overcome the lack of suitable and stable Ra ligands. A significant step forward was the binding of radium by its encapsulation or surface sorption in the NPs of suitable composition or by the sorption of Ra on the surface of various nanomaterials. An overview of selected 223Ra chelator-free labeled nanomaterials is given in Table 5. The inspiration from the naturally occurring alkali-earth element minerals with low solubilities like gypsum (CaSO4), celestine (SrSO4), or barite (BaSO4) (Rosenberg et al. 2018) could be expected. Ionic size and chemistry of Ra allow various methods for its incorporation like isostructural incorporation, pores intrusion, ion exchange, etc.

It is important to mention that the intended use of nanomaterials also had second motivation. That was to solve the problem of the daughter radioactive nuclei release from the targeting molecules due to the nuclear recoil effect since their spread over the body causes unwanted irradiation of healthy tissues. In this way, at least partial retention of radioactive progeny should improve the overall therapeutic outcome (Kozempel et al. 2018). On the other hand, controlled release of daughter progeny from a point source in close vicinity of tumors was reported to improve the treatment outcome in so-called DART (diffusing alpha-emitters radiation therapy) localized tumor therapy (Popovtzer et al. 2020; Keisari and Kelson 2021) and could be possibly transferred to other alpha particle therapy modalities (Perrin et al. 2022).

In addition to the properties of the neat nanomaterials used for successful Ra binding, the surface of the nanomaterials offers a possibility of additional modification such as protective coating, binding of active targeting moieties, attaching chelators, etc. (Trujillo-Nolasco et al. 2021). Even though the results of in vitro tests of labeled nanomaterials may indicate very promising findings, their translation into advanced in vivo preclinical and clinical stages of research is not straightforward. It would definitely bring novel obstacles and challenges for their systemic application, e.g., an unspecific uptake in RES, problematic active targeting, barriers crossing, toxicity, etc. (Lankoff et al. 2021; Kleynhans et al. 2021). However, further research is needed to elucidate the overall fate of the radiolabeled nanomaterials in vivo, such as active or passive transport to the tumor, the tumor microenvironment modification, immunogenic tumor-cell death, etc.

Unfortunately, there are still only very few in vivo studies available on the Ra-labeled nanomaterials intended for use in nuclear medicine. This may relate to the previous, relatively low availability of Ra for research purposes. Translation of nanomaterials to clinical trials/practice is thus the next important step in future research. This research could be promoted by the Good Manufacturing Practices grade 223Ra readily available on the market. It could be expected that due to future implementation of other MCRPC treatment protocols employing 177Lu, 225Ac and 227Th labeled PSMA derivatives or antibodies (Kratochwil et al. 2016; Rosar et al. 2021; Hagemann et al. 2020; Juzeniene et al. 2021) together with restricted Ra chloride palliation, therapy (EMA/500948/2018 2018), its availability may further increase for advanced therapies research based on Ra. Promising results in the study of malignant ovarian epithelial tumors have been reported by using another alpha-emitting radium isotope—224Ra (3.66 d). For this purpose, 224Ra-labeled calcium carbonate microparticles were prepared (Westrøm et al. 2018). Studies on ES-2 and SKOV3-luc models were performed, and intraperitoneal treatment with 224Ra-microparticles gave a significant antitumor effect with either considerably reduced tumor volume or a survival benefit. The combination of 223Ra (or 224Ra) and nanomaterials or micromaterials yields multimodality, which may bring an interesting therapeutical effect with a safety profile at an effective dose. This alpha radiation tool seems to be still promising for loco-regional treatment.

Liver radioembolization as a successful experience using radiolabeled microspheres

Radioembolization with radiolabeled microspheres is a radiation-based therapy modality used to treat primary liver tumors and metastases, which are untreatable by surgery or chemotherapy. The treatment consists in the employment of microspheres that contain therapeutic radioisotopes (β-emitters such as yttrium-90 or holmium-166) (Spa et al. 2018). Although several clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of radioembolization (Hilgard et al. 2010; Kennedy et al. 2012; Rosenbaum et al. 2013), the displacement of a fraction of the administered particles towards the microvasculature of the lung instead of the liver remains a challenge. In order to overcome this issue, several approaches and new nanosystems have been proposed. For instance, Zhao et al. (2016b) have proposed the use of chelate-free radioactive nanoparticles taking advantage of radioisotopes and their non-radioactive isotopes of the same element as integral components of nanoparticles. In this direction, they synthesized chelate-free 64Cu-doped copper sulfide nanoparticles with a mean size of 11.7 nm and with high radiochemical yield. Also, Jamre et al. (2018) have prepared carrier-free 188Re loaded poly (L-lactic acid) (PLLA) microspheres through 188Re sulfide colloidal nanoparticles (188Re -SCNPs). The microspheres presented a modal size of 29 μm and radiolabeling efficiency > 99%. The biodistribution after intravenous injection in healthy BALB/c mice showed high accumulation in lung as a first capture pathway organ for microsphere.

Toxicity of nanoparticles

The toxicity of nanoparticles is a concern and may limit its use. Several factors have an influence on the toxicity of nanoparticles, like size, shape, surface, charge composition, solubility, and aggregation. Due to their high surface area, nanoparticles can easily interact with cellular components such as nucleic acids, proteins, fatty acids, and carbohydrates. Also, the small size facilitates cell entrance, which may result in nucleus interaction as the influence in several inner mechanisms/organelles of the cell, for instance, the mitochondria. Also, the surface charge of nanoparticles has a pronounced effect. The higher the nanoparticle’s positive charge, the greater electrostatic interactions it has with the cell and, thus, greater endocytic uptake (Sengul and Asmatulu 2020; Niazi et al. 2009; Huang et al. 2017).

Many in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that exposure to nanoparticles could induce the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS generation is directly related to alteration in mitochondrial metabolism, which represents one of the main markers confirming apoptosis induction since ROS causes oxidative stress, inflammation, and subsequent damage to proteins, cell membranes, and DNA (Huang et al. 2017; Freire et al. 2021; Wigner et al. 2021).

Helal-Neto et al. (2020) evaluated the toxicity effect of polylactic acid (PLA) nanoparticles and magnetic core mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MMSN) of 1000 nm and 50 nm, respectively. The nanoparticles were analyzed in the following cell lines: melanoma (MV3), breast cancer (MCF-7, MDA-MB-213), glioma (U373MG), prostate (PC3), gastric (AGS) and colon adenocarcinoma (HT-29), melanocyte (NGM), fibroblast (FGH) and endothelial (HUVEC), evaluating cell migration, tubulogenesis, tubulin, AKT, GADPH, ERK, actin skeleton, and several other parameters. The results demonstrated that neither PLA nor MMSM nanoparticles could produce a toxic effect. Controversially, Wigner et al. (2021) evaluating the influence of polymeric nanoparticles (PLA/MMT/TRA, PLA/EDTMP, PLGA/MDP, and Pluronic F127 Ms) on the cell, homeostasis demonstrated that all nanosystems were able to produce a toxic effect, which included: genotoxicity effect by internucleosomal DNA fragmentation and formation of ROS. In the same way, Freire et al. (2021), studying the biomedical application of graphitic carbon nitrides nanoparticles, found that although graphitic carbon nitrides may induce cell apoptosis, the mechanism was not by the formation of ROS formation.

Regarding the toxicity of metallic nanomaterial, it depends on the oxidation state, ligands, solubility, and morphology as the health conditions of the subject. Although the complete mechanism where metallic nanoparticles produce toxic events is unknown, researchers believe that metallic nanoparticles can be toxic due to the release of ions and disbursing throughout the body (Długosz et al. 2020). The number of ions released generates a cascade of events, culminating with a high amount of ROS, leading to increased inflammation, mitochondrial perturbation secretion of lactate dehydrogenase, damage to DNA, proteins, and lipids ended in death by apoptosis or necrosis (Rasmussen et al. 2010). A study by Yao et al. (2019) has shown that metal nanoparticles and metal oxides nanoparticles (nano-Cu, nano-Ag, nano-Ni, nano-TiO2, nano- ZnO, and nano-Au) have a high accumulation in the liver and the mononuclear phagocytic system after reaching the systemic circulation, which resulted in the interaction of these nanoparticles with hepatic cells, with the possibility of changing the structure and function of hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, liver sinusoidal endothelial cells, hepatic stellate cells, and others. This is corroborated by Attarilar et al. (2020) that have discussed in a review study that the main mechanism involved in toxicity of metallic nanoparticles are: i) ROS formation, ii) cell damage by membrane perforation, iii) cytoskeleton damage, iv) mutagenesis, v) mitochondrial damage and vi) lysosome damage. It is important to notice that there is no information regarding specific toxicity of radioactive metallic nanoparticles, and it could be an important field of study.

The functionalized metal NPs can be either actively or passively delivered to the target site for specific therapy. Thus, the fabrication and functionalization of nanomaterials can be effectively carried out for attaining antimicrobial and anticancer properties. Functionalization modifies the physicochemical properties of nanomaterials thereby altering toxicity to a minimal level, enhancing protein adsorption, and affecting cellular activity. Also, functionalization increases the solubility of nanomaterials and their escape from primary immune reactions that results in strengthening the possibility of using nanomaterials as carriers of biological and therapeutic molecules without affecting the immune system (Veerapandian et al. 2014).

Discussion

Nanoparticles used for biomedical applications have several advantages compared to conventional drugs. It is worth highlighting the improvement of bioavailability, the increased biological half-life, increased targeting, and higher bioaccumulation. Nanoparticles show a surface-to-volume ratio, which allows the encapsulation of diverse therapeutics molecules: radionuclides, contrast agents, aptamers, peptides, and many other compounds (Corrêa et al. 2022; Magne et al. 2021b; Jeong et al. 2018; Kim et al. 2017). Due to the high surface area, physical adsorption or electrostatic interactions insert some active ingredients, like radionuclides. Besides that, the high surface allows immobilization of therapeutics by chemistry functionalization, changing the in vivo behavior of this nanoparticle as well as increasing the target (Liu et al. 2020; Yetisgin et al. 2020; Castillo et al. 2018; Welch et al. 2009; Wu et al. 2020b).

A disadvantage of nanoparticles is thatafter reaching the bloodstream, they are prone to aggregation and protein opsonization. Both processes alert the immune systems, leading to a massive clearing of the nanoparticles from the bloodstream with high uptake by the liver, spleen, and kidney. This rapid and non-specific clearance by the immune system results in decreased retention time and thus limits bioavailability (Santos et al. 2017).

There are several advantages and many limitations on the use of nanoparticles. For instance, variations on the surface charge (zeta potetntial), morphology and size may change drastically the behavior of the nanosystems in the cellular and molecular level. Most nanoparticles enter the cells by endocytosis through clathrin- or caveolae-dependent mechanisms (Behzadi et al. 2017). In both cases, the shape of nanoparticles plays an important role in biodistribution and, subsequentially, the internalization by cells. For instance, rod-shaped cationic nanoparticles are easier targets for endosomal uptake than cationic nanoparticles of other shapes, suggesting that these nanoparticles may be comprehended by immune system cells as rod-shaped bacteria (Gratton et al. 2008). Finally, surface charge also plays an essential whole in the biodistribution and targeting of nanoparticles. Positively charged nanoparticles are taken up to more extent by liver hepatocytes when compared to uncharged. Meanwhile, negatively charged nanoparticles show a broader liver distribution (Elci et al. 2016). According to He et al. (He et al. 2010), negative charged NPs tended to accumulate in tumors more efficiently, and Frolich (Fröhlich 2012) stated that positively charged nanoparticles are more cytotoxic than negative variants of similar size.

Therefore, the design of the nanoparticles depends on further application. This review paper revisited the current status of the radiolabeled nanoparticles for molecular imaging and radionuclide therapy. We overview the nanoparticles labeled with imaging (99mTc and 64Cu) and therapeutic (177Lu and 223Ra) radiometals. Unfortunately, most of these radiolabeled NPs have only been assessed at preclinical settings, while just a few are clinically approved. The 99mTc-labeled NPs for sentinel lymph node, the 99mTc-labeled microparticles for lung perfusion imaging as well as the 90Y/166Ho-labeled microspheres for liver radioembolization were the first clinically approved a few years ago, and the unique that is in the clinic to date, to the best of our knowledge.

64Cu-NPs have some challenges: they must have superior kinetic inertness to Cu(II) decomplexation (proton-assisted as well as transchelation or transmetallation) to avoid undesirable uptake in healthy tissues (e.g., liver) when is injected into a living organism (Wadas et al. 2007). Hence, the stable Cu complexation is sometimes a crucial challenge in the 64Cu radiopharmaceuticals. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, we did not find any findings regarding this in the case of the 64Cu-labeled NPs. Perhaps because many NPs can be eliminated with the physiological uptake in healthy tissue (liver, spleen) due to the opsonization, or maybe because of the high in vivo stability of 64Cu-labeled NPs. Still, 64Cu-labeled NPs displayed promising outcomes at preclinical settings for monitoring the efficacy of therapies, like chemotherapy, and for new treatment planning using molecular imaging. Currently, there is a clinical trial phase 1 under recruiting (NCT04167969) to evaluate 64Cu-labeled NPs to guide the surgical treatment of prostate cancer (NCT04167969).

Unlike 99mTc, 64Cu, and 177Lu, the stable chelation of the alkaline earth metal 223Ra is a challenge (Abou et al. 2021; Lankoff et al. 2021) because of its complete electronic configuration ([Rn]7s2) and the recoil energy effect. Hence, properly designed encapsulating of 223Ra in nanomaterials such as micelles (Hilgard et al. 2010) or surface sorption onto NPs might be the solution to get new 223Ra radiopharmaceuticals for alpha-targeted therapy. Also, these strategies might solve the problem of the daughter radioactive nuclei release from the 223Ra-labeled molecules. Although a few findings with 223Ra-labeled NPs (very little) have been reported, still in vivo evidence that validates the previous hypotheses is a lack. Figure 5 shows the main approaches used for radiolabeling the overviewed NPs using or not chelate-complexation, both with high radiochemical stability (reported in most studies).

Radiolabeling of nanoparticles using chelate or chelate-free approaches. NP, nanoparticle; SF, surface functionalization; RN, radionuclide (99mTc, 64Cu, 177Lu, 223Ra); AuNPs, gold nanoparticles; AGuIX, gadolinium nanoparticles; SiGdNP, silica gadolinium nanoparticles; MnFe2O4, superparamagnetic manganese ferrite; CQDs, carbon quantum dots; nMOFs, nanoscale metal–organic frameworks; Fe-Ga-CPNs, iron-gallic acid coordination nanoparticles

As previously mentioned, nanoparticles have excellent properties for designing therapeutic radiopharmaceuticals: high surface-to-volume ratio, easy surface modification, EPR effect, improved bioavailability, and increased biological half-life. For in vivo applications, toxicity might be the most increased limitation of NPs. However, PEGylation might overcome that limitation. Among the reviewed works, 177Lu-labeled NPs are the most preclinically evaluated for radionuclide therapy and theranostics with positive therapeutic effects and low perceptible physiological toxicity. Target-specific functionalization enhanced tumor accumulation and retention as well as the therapeutic effect. Moreover, some 177Lu-labeled NPs combined radionuclide therapy with other therapies such as chemotherapy and immunotherapy in one-pot delivery. Still, some preclinical studies used intratumoral injection instead of intravenous to evaluate the therapeutic effect of the 177Lu-labeled NPs. As a proof-a-concept, the intratumoral injection may be accepted. However, in vivo studies using intravenous injection are needed to evaluate the biodistribution and pharmacokinetics as well as to demonstrate better the safe and effective use of the radiolabeled NPs for cancer therapy. In addition, we suggest the use of metastatic preclinical models to evaluate their therapeutic effect and safety in a closer approximation to the clinical settings before clinical translation. To the best of our knowledge, we did not find ongoing clinical trials with 177Lu-labeled NPs yet.

Therefore, the lack of clinical outcomes, mainly in the last five years, limits us to conclude that the radiolabeled nanomaterials for biomedical applications are the future of radiopharmacy. Despite the advantages of the nanoparticles over macromolecules, there is a long way to go and much more work to do for demonstrating the future use of the radiolabeled nanoparticles in radiopharmacy.

Conclusions and outlook

In this review, the data demonstrated that in some cases, the use of radiolabeled nanoparticles might increase the quality of the therapy as well as the imaging. The development of theranostic nanoparticles may represent an important advance in the radiopharmacy field and may represent the last frontier. Although several benefits have been described in the use of radioactive nanoparticles, there are also several limitations. One of the most prominent limitation is the rapid recognition of nanoparticles (radioactive or not) by the mononuclear phagocyte system, leading to the rapid elimination of nanoparticles from the bloodstream. Another issue is the corona protein formation, which also leads to accelerated elimination and inactivation of the nanoparticles. Finally, the toxicity of metals and radioactive metals must be underlined since several particularities must be better understood.

In this direction, some outlooks are proposed:

Understand the stability of organic and inorganic nanoparticles, especially with beta and alpha emitters radionuclides;

Understand the differential toxicity of metals and radioactive metals;

Think in new forms to avoid the mononuclear phagocyte system. Promising results were recently reported with NPs using the differential esterase activity in organs (Lee et al. 2021) or enzyme-powered nanomotors (Hortelao et al. 2021).

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- 125I:

-

Iodine-125

- 131Ba:

-

Barium-131

- 14C:

-

Carbon-14

- 177Lu:

-

Lutetium-177

- 199Au:

-

Gold-199

- 223Ra:

-

Radium-223

- 4-DEAP-ATSC:

-

Diacetyl 4,4′-bis(3-(N,N-diethylamino)propyl)thiosemicarbazone

- 64Cu:

-

Copper-64

- 68 Ga:

-

Gallium-68

- 89Zr:

-

Zirconium-89

- 90Y:

-

Yttrium-90

- 98Mo:

-

Molybdenum-98

- 99mTc:

-

Technetium-99m

- AGuIX:

-

Gadolinium nanoparticles

- ATSM:

-

Diacetyl bis(N 4-methylthiosemicarbazone)

- AuNCs:

-

Gold nanoclusters

- AuNPs:

-

Gold nanoparticles

- Barite:

-

BaSO4

- CB-TE2A:

-

4,11-Bis(carboxymethyl)-1,4,8,11-tetraazabicyclo[6.6.2]hexadecane

- Celestine:

-

SrSO4

- CH:

-

Chitosan

- CNC:

-

Cellulose nanocrystals

- CNS:

-

Carbon nanospheres

- CQDs:

-

Carbon quantum dots

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- Cubosomes:

-

Lipidic cubic-phase nanoparticles

- CuS:

-

Copper sulfide

- cys-DB:

-

Cysteine-diabody

- DART:

-

Diffusing alpha-emitters radiation therapy

- DN:

-

Dendrimers

- DOTA:

-

1,4,7,10-Tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid

- DOX:

-

Doxorubicin

- DTPA:

-

Diethylenetriamine pentaacetate

- EDTA:

-

2,2′,2″,2‴-(Ethane-1,2-diyldinitrilo)tetraacetic acid or ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid

- EMA:

-

European Medicines Agency

- EPR:

-

Enhanced permeability and retention

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- Fe3O4–SiO2 :

-

Iron oxide bound to silica

- Fe-GA-CPNs:

-

Iron-gallic acid coordination nanoparticles

- FR:

-

Folate receptors

- GRPr:

-

Gastrin-releasing peptide receptors

- GSH:

-

Glutathione

- Gypsum:

-

CaSO4

- HER2:

-

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- HMPAO:

-

D,l-Hexamethylene-propyleneamine oxime

- HSA:

-

Human serum albumin

- i.v.:

-

İNtravenous

- IUPAC:

-

International Union of Pure and-Applied Chemistry

- LET:

-

Linear energy transfer

- LND:

-

Lipid nanodiscs

- LNPs:

-

Lipid nanoparticles

- Lu2O3 :

-

Rare sesquioxides

- MAA:

-

Macroaggregated albumin

- Macrin:

-

Polyglucose nanoparticles

- MCRPC:

-

Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer

- MMSN:

-

Magnetic core mesoporous silica nanoparticles

- MnFe2O4 :

-

Superparamagnetic manganese ferrite

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MSNPs:

-

Mesoporous silica nanoparticles

- NLS:

-

Nuclear localization sequence

- nMOFs:

-

Nanoscale metal–organic frameworks

- NODAGA:

-

1,4,7-Triazacyclononane, 1-glutaric acid-4,7-diacetic acid

- NOTA:

-

1,4,7-Triazacyclononane-N,N′,N″-trisacetic acid

- NPs:

-

Nanoparticles

- PCN-224:

-

Zirconium-based nMOFs

- PD-1:

-

Programmed cell death-1

- PEG:

-

Polyethylene glycol

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- PLA:

-

Polylactic acid

- PLLA:

-

Poly(l-lactic acid)

- PTX:

-

Paclitaxel

- RES:

-

Reticuloendothelial system

- RGD:

-

Arg-Gly-Asp

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- SCNPs:

-

Sulfide colloidal nanoparticles

- SiGdNPs:

-

Silica gadolinium nanoparticles

- SLNs:

-

Solid lipid nanoparticles

- SPECT:

-

Single-photon emission computed tomography

- SPION:

-

Superparamagnetic iron oxide

- TETA:

-

1,4,8,11-Tetraazacyclotetradecane-1,8-diacetic acid

- UPS:

-

Ultra-pH sensitive

- V:

-

Vemurafenib

- VEGF:

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor

References

Abdin Z, Alim MA, Saidur R, Islam MR, Rashmi W, Mekhilef S, et al. Solar energy harvesting with the application of nanotechnology. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2013;26:837–52.

Abou DS, Thiele NA, Gutsche NT, Villmer A, Zhang H, Woods JJ, et al. Towards the stable chelation of radium for biomedical applications with an 18-membered macrocyclic ligand. Chem Sci. 2021;12(10):3733–42.

Ahmadi MH, Ghazvini M, Alhuyi Nazari M, Ahmadi MA, Pourfayaz F, Lorenzini G, et al. Renewable energy harvesting with the application of nanotechnology: a review. Int J Energy Res. 2019;43(4):1387–410.

Ahmadzadehfar H, Rahbar K, Essler M, Biersack HJ. PSMA-based theranostics: a step-by-step practical approach to diagnosis and therapy for mCRPC patients. Semin Nucl Med. 2020;50(1):98–109.

Ahmedova A, Todorov B, Burdzhiev N, Goze C. Copper radiopharmaceuticals for theranostic applications. Eur J Med Chem. 2018;157:1406–25.

Alnaaimi M, Sulieman A, Alkhorayef M, Salah H, Alduaij M, Algaily M, et al. Organs dosimetry in targeted radionuclide therapy. Radiat Phys Chem. 2021;188:109668.

Ancira-Cortez A, Ferro-Flores G, Jiménez-Mancilla N, Morales-Avila E, Trujillo-Benítez D, Ocampo-García B, et al. Synthesis, chemical and biochemical characterization of Lu2O3-iPSMA nanoparticles activated by neutron irradiation. Mater Sci Eng C. 2020;117:111335.

Ancira-Cortez A, Trujillo-Benítez D, Jiménez-Mancilla N, Santos-Cuevas C, Morales-Avila E, Ferro-Flores G. Synthesis and physicochemical characterization of Lu and Sm sesquioxide nanoparticles by precipitation-calcination and pulsed laser ablation in liquids. Mater Chem Phys. 2021;275:125229.

Andorko JI, Hess KL, Pineault KG, Jewell CM. Intrinsic immunogenicity of rapidly-degradable polymers evolves during degradation. Acta Biomater. 2016;32:24–34.

Aquib M, Farooq MA, Banerjee P, Akhtar F, Filli MS, Boakye-Yiadom KO, et al. Targeted and stimuli–responsive mesoporous silica nanoparticles for drug delivery and theranostic use. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2019;107(12):2643–66.

Attarilar S, Yang J, Ebrahimi M, Wang Q, Liu J, Tang Y, et al. The toxicity phenomenon and the related occurrence in metal and metal oxide nanoparticles: a brief review from the biomedical perspective. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:822.

Baetke SC, Lammers T, Kiessling F. Applications of nanoparticles for diagnosis and therapy of cancer. Br J Radiol. 2015;88:1–12.

Ballinger JR. Theranostic radiopharmaceuticals: established agents in current use. Br J Radiol. 2018;91(1091):20170969.

Banerjee S, Pillai MRA, Knapp FF. Lutetium-177 therapeutic radiopharmaceuticals: linking chemistry, radiochemistry, and practical applications. Chem Rev. 2015;115(8):2934–74.

Barua S, Mitragotri S. Challenges associated with penetration of nanoparticles across cell and tissue barriers: a review of current status and future prospects. Nano Today. 2014;9(2):223–43.

Behzadi S, Serpooshan V, Tao W, Hamaly MA, Alkawareek MY, Dreaden EC, et al. Cellular uptake of nanoparticles: journey inside the cell. Chem Soc Rev. 2017;46(14):4218–44.

Bernardos A, Piacenza E, Sancenón F, Hamidi M, Maleki A, Turner RJ, et al. Mesoporous silica-based materials with bactericidal properties. Small. 2019;15(24):1900669.

Bertrand N, Wu J, Xu X, Kamaly N, Farokhzad OC. Cancer nanotechnology: the impact of passive and active targeting in the era of modern cancer biology. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014;66:2–25.

Biagiotti G, Pisaneschi F, Gammon ST, Machetti F, Ligi MC, Giambastiani G, et al. Multiwalled carbon nanotubes for combination therapy: a biodistribution and efficacy pilot study. J Mater Chem B. 2019;7(16):2678–87.

Biswas CS, Biswas A, Galluzzi M, Shekh MI, Wang Q, Ray B, et al. Synthesis and characterization of novel amphiphilic biocompatible block-copolymers of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)-b-poly(L-phenylalanine methyl ester) by RAFT polymerization. Polymer (Guildf). 2020;203:122760.

Bluemel C, Herrmann K, Giammarile F, Nieweg OE, Dubreuil J, Testori A, et al. EANM practice guidelines for lymphoscintigraphy and sentinel lymph node biopsy in melanoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42(11):1750–66.

Bobo D, Robinson KJ, Islam J, Thurecht KJ, Corrie SR. Nanoparticle-based medicines: a review of FDA-approved materials and clinical trials to date. Pharm Res. 2016;33(10):2373–87.

Boisseau P, Loubaton B. Nanomedicine, nanotechnology in medicine. C R Phys. 2011;12(7):620–36.

Buzea C, Pacheco II, Robbie K. Nanomaterials and nanoparticles: sources and toxicity. Biointerphases. 2007;2(4):M17–71.

Cai Z, Yook S, Lu Y, Bergstrom D, Winnik MA, Pignol JP, et al. Local radiation treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer using trastuzumab-modified gold nanoparticles labeled with 177Lu. Pharm Res. 2017;34(3):579–90.

Cai H, Xie F, Mulgaonkar A, Chen L, Sun X, Hsieh JT, et al. Bombesin functionalized 64Cu-copper sulfide nanoparticles for targeted imaging of orthotopic prostate cancer. Nanomedicine. 2018;13(14):1695–705.

Cao Q, Wang W, Zhou M, Huang Q, Wen X, Zhao J, et al. Induction of antitumor immunity in mice by the combination of nanoparticle-based photothermolysis and anti-PD-1 checkpoint inhibition. Nanomed Nanotechnol Biol Med. 2020;25:102169.

Castillo PM, Jimenez-Ruiz A, Carnerero JM, Prado-Gotor R. Exploring factors for the design of nanoparticles as drug delivery vectors. ChemPhysChem. 2018;19(21):2810–28.

Chakravarty R, Guleria A, Jadhav S, Kumar C, Debnath AK, Sarma HD, et al. Bioinspired synthesis of intrinsically 177Lu-labeled hybrid nanoparticles for potential cancer therapy. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2020;59(52):22492–500.

Chen D, Yang D, Dougherty CA, Lu W, Wu H, He X, et al. In vivo targeting and positron emission tomography imaging of tumor with intrinsically radioactive metal–organic frameworks nanomaterials. ACS Nano. 2017;11(4):4315–27.

Chen F, Goel S, Shi S, Barnhart TE, Lan X, Cai W. General synthesis of silica-based yolk/shell hybrid nanomaterials and in vivo tumor vasculature targeting. Nano Res. 2018;11(9):4890.

Chong KP. Nanotechnology in civil engineering—research and challenge. In: Bartoset PJM al., editors. Nanotechnology in construction (Royal Society of Chemistry, 2004—ISBN 0-85404-632-2) p. 13–22.

Cong VT, Gaus K, Tilley RD, Gooding JJ. Rod-shaped mesoporous silica nanoparticles for nanomedicine: recent progress and perspectives. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2018;15(9):881–92.

Conti M, Eriksson L. Physics of pure and non-pure positron emitters for PET: a review and a discussion. EJNMMI Phys. 2016;3(1):1–17.

Corrêa LB, Pinto SR, Alencar LMR, Missailidis S, Rosas EC, de Oliveira MDGM, et al. Nanoparticle conjugated with aptamer anti-MUC1/Y for inflammatory arthritis. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2022;211:112280.

Costa JAS, Paranhos CM. Mitigation of silica-rich wastes: an alternative to the synthesis eco-friendly silica-based mesoporous materials. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2020;309:110570.

Cui L, Xiong C, Zhou M, Shi S, Chow DSL, Li C. Integrin αvβ3-targeted [64 Cu]CuS nanoparticles for PET/CT imaging and photothermal ablation therapy. Bioconjug Chem. 2018;29(12):4062–71.

Cvjetinović Đ, Prijović Ž, Janković D, Radović M, Mirković M, Milanović Z, et al. Bioevaluation of glucose-modified liposomes as a potential drug delivery system for cancer treatment using 177-Lu radiotracking. J Control Release. 2021;332:301–11.

Cytryniak A, Nazaruk E, Bilewicz R, Górzyńska E, Żelechowska-Matysiak K, Walczak R, et al. Lipidic cubic-phase nanoparticles (cubosomes) loaded with doxorubicin and labeled with 177Lu as a potential tool for combined chemo and internal radiotherapy for cancers. Nanomaterials. 2020;10(11):2272.

Czerwińska M, Fracasso G, Pruszyński M, Bilewicz A, Kruszewski M, Majkowska-Pilip A, et al. Design and evaluation of 223Ra-labeled and anti-PSMA targeted NaA nanozeolites for prostate cancer therapy–part I. Materials (Basel). 2020;13(17):3875.

D’Abadie P, Hesse M, Louppe A, Lhommel R, Walrand S, Jamar F. Microspheres used in liver radioembolization: from conception to clinical effects. Molecules. 2021;26(13):3966.

De Barros ALB, De Oliveira Ferraz KS, Dantas TCS, Andrade GF, Cardoso VN, De SEMB. Synthesis, characterization, and biodistribution studies of 99mTc-labeled SBA-16 mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Mater Sci Eng C. 2015;56:181–8.

de Carvalho APA, Conte Junior CA. Green strategies for active food packagings: a systematic review on active properties of graphene-based nanomaterials and biodegradable polymers. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2020;103:130–43.

de Oliveira Freitas LB, de Melo CL, Faria JAQA, dos Santos VM, Resende JM, Leal AS, et al. Multifunctional mesoporous silica nanoparticles for cancer-targeted, controlled drug delivery and imaging. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2017;242:271–83.