Abstract

In this paper, stability results for the linear degenerate fractional differential system with constant coefficients are presented. First of all, the explicit representation of solution of the system is established based on the algebraic approach. Then stability criteria for the system are given, which are straightforward and suitable for application. Finally, some examples are provided to illustrate the application of the results.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Recently, fractional differential equations have become more and more important due to their varying applications in various fields of applied sciences and engineering, such as the charge transport in amorphous semiconductors, the spread of contaminants in underground water, the diffusion of pollution in the atmosphere, network traffic, etc. For details, see [1–9] and references therein.

As in classical calculus, stability analysis plays a key role in control theory. Stability analysis of linear fractional differential equations has been carried out by various researchers [10–20]. In [10], Matignon provided famous stability results for finite-dimensional linear fractional differential systems with constant coefficient matrix A. The main qualitative result is that the stability results are guaranteed iff the roots of the eigenfunction of the system lie outside the closed angular sector \(|\operatorname{arg}(\lambda(A))| \leq\frac{\pi \alpha}{2}\), which generalized the results for the integer case \(\alpha = 1\). Chen [11] studied the stability of one-dimensional fractional systems with retarded time by using Lambert function.

Many years later, Matignon’s stability results were promoted by many scholars such as Deng, etc. In [12], by using the Laplace transform, Deng generalized the system to a linear fractional differential system with multi-orders and multiple delays and discovered that the linear system is Lyapunov globally asymptotical stable if all roots of the characteristic equation have negative parts. In 2010, Odibat [13] described the issues of existence, uniqueness, and stability of the solutions for two classes of linear fractional differential systems with Caputo derivative. In [14], Qian established stability theorems for fractional differential systems with Riemann-Liouville derivative. In [15], one studied basic stability properties of linear fractional differential systems with Riemann-Liouville derivative and one derived stability regions for special discretizations of the studied fractional differential systems including a precise description of their asymptotics.

Meanwhile, Li [21, 22] was first to study the stability of fractional order nonlinear systems by applying the Lyapunov direct method with the introductions of Mittag-Leffler stability. Some valuable results have been derived on the stability of nonlinear fractional differential systems; see [23–28] and references therein. The stability of fractional differential systems has been fully studied. There is no doubt that the Lyapunov direct method provides a very effective approach to analyzing the stability of nonlinear systems. However, it is not easy to find such a suitable Lyapunov function. There are still many works that need to be improved.

As is well known, many systems are most naturally modeled by degenerate differential equations such as multibody mechanics, electrical circuits, prescribed path control, chemical engineering, etc.; see [29–33] and the references therein. Degenerate differential equations can describe more complex dynamical models than state-space systems, due to the fact that a degenerate differential system model includes not only dynamic equations but also static equations. Recently, more and more research has been devoted to the study of degenerate fractional systems. For example, in [34], the constant variation formulas for degenerate fractional differential systems with delay were presented. In [35], the exponential estimation of the degenerate fractional differential system with delay and sufficient conditions for the finite time stability of the system are obtained. In 2010, by using linear matrix inequalities, N’Doye [36] derived sufficient conditions for the robust asymptotical stabilization of uncertain degenerate fractional systems with the fractional order α, satisfying \(0 < \alpha< 2\).

However, there are very limited works that focus on the stability of degenerate fractional linear differential systems with Riemann-Liouville derivative. Motivated by [34–37], in this paper, we present the explicit representation of a solution for the degenerate fractional linear system with Riemann-Liouville derivative and derive the stability criteria for the system. The results show that the stability criterion is easy to verify.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we review basic notions and results from the theory of fractional calculus and degenerate differential system. In Section 3, we discuss the existence and uniqueness of solution for the linear degenerate fractional differential system and give the explicit representation of solutions for the system. In addition, we analyze the stability of the linear degenerate fractional differential system and achieve sufficient conditions to provide the asymptotically stability of the system. In Section 4, some examples are presented to illustrate the main results. Finally, concluding remarks are given.

2 Preliminaries

In this section, we present some related definitions and some fundamental theories as follows.

Definition 2.1

The Riemann-Liouville fractional integral operator of order \(\alpha>0\) of \(f(t)\) is defined as

and the Riemann-Liouville fractional derivative is defined as

where \(\Gamma(\cdot)\) is the gamma function. The initial time a is often set to be 0.

The Laplace transform of the Riemann-Liouville fractional derivative \(D_{0, t}^{\alpha}x(t)\) is

Definition 2.2

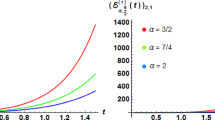

The one parameter Mittag-Leffler function \(E_{\alpha}(z)\) and the two parameter Mittag-Leffler function \(E_{\alpha,\beta}(z)\) are defined as

Their kth derivatives, for \(k=0, 1, 2, 3, \ldots \) , are given by

It can be noted that \(E_{\alpha, 1}(z)=E_{\alpha}(z)\) and \(E_{1, 1}(z)=e^{z}\). The Mittag-Leffler functions \(E_{\alpha}(z)\) and \(E_{\alpha, \beta}(z)\) are entire functions for \(\alpha, \beta>0\). According to \(E_{1, 1}(z)=e^{z}\), the Mittag-Leffler function \(E_{\alpha,\beta}(z)\) is a generalization of the exponential function \(e^{z}\) and the exponential function is a particular case of the Mittag-Leffler function. The Mittag-Leffler function plays a very important role in the theory of fractional differential equations, which is similar to the exponential function frequently used in the solutions of integer-order systems. The properties of the Mittag-Leffler functions can be found in [4, 13] and the references therein. Moreover, the Laplace transforms of the Mittag-Leffler functions are given by

where \(\lambda\in C\), \(E_{\alpha,\beta}^{k}(z)=\frac {d^{k}}{dz^{k}}E_{\alpha,\beta}(z)\), \(Res(s)\) denotes the real part of s. t and s are the variables in the time domain and Laplace domain, respectively.

Lemma 2.1

([3])

If \(0<\alpha<2\), β is an arbitrary complex number and μ is an arbitrary real number, satisfying

then, for an arbitrary integer \(N\geq1\), the following expansion holds:

-

(1)

$$E_{\alpha,\beta}(z)=\frac{1}{\alpha}z^{\frac{1-\beta}{\alpha}}\exp \bigl(z^{\frac{1}{\alpha}} \bigr)-\sum_{k=1}^{N}\frac{1}{\Gamma(\beta-\alpha k)} \frac{1}{z^{k}}+O\biggl(\frac{1}{|z|^{N+1}}\biggr), $$

with \(|z|\rightarrow\infty, |\operatorname{arg}(z)|\leq\mu\), and

-

(2)

$$E_{\alpha,\beta}(z)=-\sum_{k=1}^{N} \frac{1}{\Gamma(\beta-\alpha k)}\frac {1}{z^{k}}+O\biggl(\frac{1}{|z|^{N+1}}\biggr), $$

with \(|z|\rightarrow\infty, \mu\leq|\operatorname{arg}(z)|\leq\pi\).

Remark 2.1

In Lemma 2.1, if \(\alpha=\beta\) and \(N\geq2\), then the following expansion holds:

with \(|z|\rightarrow\infty, |\operatorname{arg}(z)|\leq\mu\);

with \(|z|\rightarrow\infty,\mu\leq|\operatorname{arg}(z)|\leq\pi\).

Consider the following linear fractional differential system:

where \(x(t)\in R^{n}\) is the state vector, \(E, A\in R^{n\times n}, \operatorname{rank}E< n, x_{0}\in R^{n}, D_{0,t}^{\alpha}\) denotes an αth order Riemann-Liouville derivative of \(x(t)\), and \(0<\alpha<1\).

Definition 2.3

The system (7) is said to be:

-

(a)

stable iff for any \(x_{0}\), there exists an \(\varepsilon>0\) such that \(\|x(t)\|\leq\varepsilon\) for \(t\geq0\);

-

(b)

asymptotically stable iff \(\lim _{t\rightarrow+\infty}\| x(t)\|=0\).

Definition 2.4

For any given two matrices \(E, A \in R^{n\times n}\), the matrix pair \((E, A)\) is called regular if \(\operatorname{det}(\lambda E-A)\not \equiv0\), where \(\lambda\in\mathcal{C}\). If \((E, A)\) is regular, we call system (7) is regular.

Definition 2.5

Let Q be a square matrix. The index of Q is the least nonnegative integer k such that \(\operatorname{rank}(Q^{k+1})=\operatorname{rank}(Q^{k})\). The Drazin inverse of Q is the unique matrix \(Q^{d}\) which satisfies

Lemma 2.2

[31]

Suppose that \(E, A\in R^{n\times n}\) are such that there exists a λ so that \((\lambda E-A)^{-1}\) exists. Let \(\hat{E}_{\lambda}=(\lambda E-A)^{-1}E, \hat{A}_{\lambda}=(\lambda E-A)^{-1}A\). For all \(\lambda_{1}\neq\lambda_{2}\) for which \((\lambda_{i}E-A)^{-1}, i=1, 2\), exist, the following statements are true:

where \(\hat{E}_{\lambda}^{d}\) is the Drazin inverse of \(\hat{E}_{\lambda }\) and I is the \(n\times n\) identity matrix.

3 Main results

3.1 The existence and uniqueness of the solution for linear degenerate fractional differential system

In this section, we consider the solvability of the following system:

where \(x(t)\in R^{n}\) is the state vector, \(A, E\in R^{n\times n}, \operatorname{rank}E< n,x_{0}\in R^{n}, D_{0,t}^{\alpha}\) denotes an αth order Riemann-Liouville derivative, and \(0<\alpha<1\).

Theorem 3.1

If the system (8) is regular, then the system (8) has a unique solution on \([0, +\infty)\) and the solution is given by

where \(e_{\alpha}^{\hat{E}_{\lambda}^{d}\hat{A}_{\lambda}t}\)= \(t^{\alpha -1}\sum _{k=0}^{\infty} (\hat{E}_{\lambda}^{d}\hat{A}_{\lambda })^{k}\frac{t^{k\alpha}}{\Gamma[(k+1)\alpha]},\hat{E}_{\lambda}=(\lambda E-A)^{-1}E, \hat{A}_{\lambda}=(\lambda E-A)^{-1}A\), \(x(0)\) satisfies \(x(0)=\hat{E}_{\lambda}\hat{E}_{\lambda}^{d}x(0)\). E and A are the coefficient matrices of the system (8), and λ is constant.

Proof

Since the system is regular, there exists a λ so that \((\lambda E-A)^{-1}\) exists. Let \(\hat{E}_{\lambda}=(\lambda E-A)^{-1}E,\hat{A}_{\lambda}=(\lambda E-A)^{-1}A\). From Lemma 2.2 and [31], there exists an invertible matrix T such that

where \(C\in R^{p\times p}\) is invertible matrix, \(N\in R^{q\times q}\) is nilpotent, and \(q+p=n\).

Then

Premultiplying \((\lambda E-A)^{-1}\) on both sides of the formula \(ED^{\alpha}x(t)=Ax(t)\), then

Taking the transform as \(\xi(t) =\bigl ( {\scriptsize\begin{matrix}{} \xi_{1}(t)\cr \xi_{2}(t) \end{matrix}} \bigr )=Tx(t) , \xi_{1}(t)\in R^{p},\xi_{2}(t)\in R^{q}\), and \(\xi(0) =\bigl ( {\scriptsize\begin{matrix}{} \xi_{1}(0)\cr \xi_{2}(0) \end{matrix}} \bigr )=Tx(0)\) such that (12) is r.s.e. to

First we discuss the first subsystem (13). Since C is an invertible matrix, (13) can be rewritten as

From the theory of fractional calculus [37], a unique solution for subsystem (13) exists, which may be expressed by

Next, we study the second subsystem (14) as follows.

Let \(\operatorname{ind}(N)=k\), that is, \(N^{k-1}\neq0, N^{k}=0\), k is the index of the matrix pair \((E, A)\). Premultiplying \(N^{k-1}\) on both sides of equation (14), then

Since \(N^{k}=0\), we get \(N^{k-1}\xi_{2}(t)=0\).

Premultiplying \(N^{k-2}\) on both sides of equation (14), then \(N^{k-2}\xi_{2}(t)=0\). In the same way, we can get

Then we can get \(\xi_{2}(t)\equiv0\).

From the above discussion, the unique solution of the system (13) and (14) is given by

Applying \(x(t)=T^{-1}\xi(t)\), the solution of (8) is given by

From [34], Lemma 2.1, one can get

Then

Then

where \(x(0)\) satisfies \(x(0)=\hat{E}_{\lambda}\hat{E}^{d}_{\lambda}x(0)\). According to Lemma 2.2, we know that \(\hat{E}^{d}_{\lambda}\hat{A}_{\lambda},\hat{E}_{\lambda}\hat{E}^{d}_{\lambda}\) are independent from λ. Hence, the system (8) has a unique solution \(x(t)=e_{\alpha }^{\hat{E}^{d}_{\lambda}\hat{A}_{\lambda}t}\hat{E}_{\lambda}\hat{E}^{d}_{\lambda}x(0)\). The proof is completed. □

Remark 3.1

From Lemma 2.2, one shows that \(\hat{E}^{d}_{\lambda}\hat{A}_{\lambda},\hat{E}_{\lambda}\hat{E}^{d}_{\lambda}\) are independent from λ. Therefore, we can drop the subscript λ whenever the terms \(\hat{E}^{d}_{\lambda}\hat{A}_{\lambda}\) and \(\hat{E}_{\lambda}\hat{E}^{d}_{\lambda}\) appear. Hence, the solution of the system (8) can be given by

where \(e_{\alpha}^{\hat{E}^{d}\hat{A}t}\)= \(t^{\alpha-1}\sum _{k=0}^{\infty} (\hat{E}^{d}\hat{A})^{k}\frac{t^{k\alpha}}{\Gamma [(k+1)\alpha]},\hat{E}=\hat{E}_{\lambda}=(\lambda E-A)^{-1}E, \hat{A}=\hat{A}_{\lambda}=(\lambda E-A)^{-1}A\), and \(x(0)\) satisfies \(x(0)=\hat{E}\hat{E}^{d}x(0)\). E and A are the coefficient matrices of the system (8), and λ is constant.

3.2 Stability results for linear degenerate fractional differential system

In this section, we derive the conditions for the asymptotically stable of the system (8).

Theorem 3.2

If the system (8) is regular, the algebraic and geometric multiplicities are the same for the zero eigenvalues of \(\hat{E}^{d}\hat{A}\) and all the non-zero eigenvalues satisfy

then the system (8) is asymptotically stable.

Proof

From Theorem 3.1 and Remark 3.1, we know that the solution of the system (8) is given by

Applying (10) and (19), one gets

where λ is constant, \((\lambda E-A)\) is invertible and \(C^{-1}(\lambda C-I)\in R^{p\times p}\).

Then there exists an invertible matrix H such that

where \(J_{i}, 1\leq i \leq r\), are Jordan canonical forms and 0 is a zero matrix with corresponding dimension.

Without loss of generality, assume that the numbers of non-zero eigenvalues and zero eigenvalues are p and q for \(\hat{E}^{d}\hat{A}\), separately. For the situation of non-zero eigenvalues, we discuss the problem in two cases.

Case (i): Assuming the matrix \(\hat{E}^{d}\hat{A}\) is diagonalizable, and \(\lambda_{1},\lambda_{2}, \ldots,\lambda_{p}\), are its non-zero eigenvalues, then (21) can be shown to obey

Hence,

From Lemma 2.1 and the conditions of Theorem 3.2, we get

where \(1\leq i \leq p\).

Hence,

Thus, the conclusion proved.

Case (ii): Assume \(E^{d}\hat{A}\) is similar to a Jordan canonical form as (21).

Let \(J_{i}, 1\leq i \leq r\), have the form

then

We can get the following results by calculation:

Under the conditions of Theorem 3.2, we can get

also, under the condition of \(|\operatorname{arg}(\lambda_{i})|>\frac {\alpha\pi}{2}\) and from Theorem 4 in [10], we have \(\frac {1}{(l-1)!}(\frac{\partial}{\partial\lambda_{i}})^{l-1}E_{\alpha,\alpha }(\lambda_{i}t^{\alpha})\rightarrow0 \) as \(t\rightarrow+\infty\), which is derived from

where \(1\leq l\leq n_{i}\) and \(1\leq i \leq r \).

Hence,

From the discussion of the above two cases, we get

The proof is completed. □

Theorem 3.3

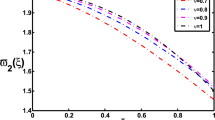

If the system (8) is regular, the zero eigenvalues of \(\hat{E}^{d}\hat{A}\) are such that their algebraic multiplicities are larger than their geometric multiplicities, \(\breve{n}\alpha<1\), in which, n̆ is the max dimension value for the Jordan canonical blocks of zero eigenvalues, and all the non-zero eigenvalues satisfy

then the system (8) is asymptotically stable.

Proof

According to Theorem 3.2, there exists an invertible matrix H, such that

where \(J_{i}\), is a Jordan canonical form, \(1\leq i \leq r\), and 0 is a zero matrix with corresponding dimension.

Let \(J_{\breve{n}}\) be the zero eigenvalues of \(\hat{E}^{d}\hat{A}\) corresponding to the following Jordan canonical form with order n̆:

Applying (22), we get

from (26) and the condition \(\breve{n}\alpha<1\), we get

The result is also satisfied for Jordan canonical blocks of zero eigenvalues, with lower dimension than \(J_{\breve{n}}\). Other Jordan canonical forms in (24), corresponding to all the non-zero eigenvalues of \(\hat{E}^{d}\hat{A}\), can be treated as the same method conducted in Theorem 3.2. The proof is completed. □

Theorem 3.4

If the system (8) is regular, the algebraic and geometric multiplicities are the same for the zero eigenvalues of \(\hat{E}^{d}\hat{A}\) and all the non-zero eigenvalues satisfy

moreover, the algebraic and geometric multiplicities are the same for the critical eigenvalues, satisfying \(|\operatorname{arg}(\lambda(\hat{E}^{d}\hat{A}))|=\frac{\alpha\pi}{2}\), then the system (8) is stable.

Proof

According to Theorem 3.2, there exists an invertible matrix H, such that

where \(J_{i}\), is a Jordan canonical form, \(1\leq i \leq r\), and 0 is a zero matrix with corresponding dimension.

From the conditions of Theorem 3.4, without loss of generality, we suppose that the eigenvalue \(\lambda_{s}\) satisfies \(|\operatorname{arg}(\lambda(\hat{E}^{d}\hat{A}))|=\frac{\alpha\pi}{2}\) with algebraic and geometric multiplicity both equal to 1, as well as \(\lambda_{s}=J_{s},1\leq s\leq r\), \(\lambda_{s}=r_{0}(\cos(\frac{\alpha\pi}{2})+i_{0}\sin(\frac{\alpha \pi}{2}))=r_{0}e^{\frac{\alpha\pi}{2}i_{0}}, (i_{0})^{2}=-1\).

Then

Applying Lemma 2.1, we get

Then

when \(t\rightarrow+\infty\), we get

From the above discussion, we can see that \(t^{\alpha-1}E_{\alpha,\alpha }(\lambda_{s}t^{\alpha}) \) is stable as \(t\rightarrow+\infty\). Other Jordan canonical forms in (28) can be treated by the same method as used in Theorem 3.2. Hence, the system (8) is stable. The proof is completed. □

Theorem 3.5

If the system (8) is regular, the zero eigenvalues of \(\hat{E}^{d}\hat{A}\) are such that their algebraic multiplicities are larger than their geometric multiplicities, \(\breve{n}\alpha<1\), in which n̆ is the max dimension value for the Jordan canonical blocks of zero eigenvalues, and all the non-zero eigenvalues satisfy

moreover, the algebraic and geometric multiplicities are the same for the critical eigenvalues, satisfying \(|\operatorname{arg}(\lambda(\hat{E}^{d}\hat{A}))|=\frac{\alpha\pi}{2}\), then the system (8) is stable.

Proof

According to Lemma 2.1 and the conditions of Theorem 3.5, the following proof is similar to Theorems 3.3, 3.4 and will be omitted. □

Theorem 3.6

For the system (8), if all the roots of the characteristic equation \(|s^{\alpha}E-A|=0\) have negative real parts, then the system is asymptotically stable.

Proof

Taking the Laplace transform on both sides of system (8), we get the characteristic equation of system (8) as follows:

Let \(\lambda=s^{\alpha}\), then

Next, we prove that the characteristic equations, \(|\lambda E-A|=0\) and \(|\lambda I-\hat{E}^{d}\hat{A}|=0\), have the same non-zero eigenvalues.

In fact, from (20) in Theorem 3.2, there exist a ρ and an invertible matrix T such that

where ρ is constant, \((\rho E-A)\) is invertible, and \(C^{-1}(\rho C-I)\in R^{p\times p}\).

Then

Premultiplying \(|(\rho E-A)^{-1}|\) on both sides of \(|\lambda E-A|=0\) and applying (9), (10), we have

Since N is nilpotent, we get

Hence,

From (32) and (34), we can see that the characteristic equations, \(|\lambda E-A|=0\) and \(|\lambda I-\hat{E}^{d}\hat{A}|=0\), have the same non-zero eigenvalues.

According to the conditions of Theorem 3.6, assume \(\lambda_{1}, \lambda _{2}, \ldots, \lambda_{m}\) are all non-zero roots of \(|\lambda E-A|=0\). \(n_{i}\) is the multiplicity of \(\lambda_{i}, 1\leq i\leq m\), and \(n_{1}+n_{2}+\cdots+n_{m}< n\). From the above discussion, we know that \(\lambda_{1}, \lambda_{2}, \ldots, \lambda_{m}\) are all non-zero roots of \(|\lambda I-\hat{E}^{d}\hat{A}|=0\) and they are also all non-zero roots of \(|\lambda I-C^{-1}(\rho C-I)|=0\).

Two cases, whether there are multiple roots among \(\lambda_{1},\lambda _{2},\ldots,\lambda_{m}\) or not, will be discussed.

First, suppose that the matrix \(C^{-1}(\rho C-I)\) is diagonalizable, i.e., there exists an invertible matrix P such that

From (31), let \(H=T\bigl ( {\scriptsize\begin{matrix}{} P&0\cr 0&I \end{matrix}} \bigr )\), then

Hence,

Due to \(\lambda=s^{\alpha}\), \(|\operatorname{arg}(\lambda)|=|\operatorname{arg}(s^{\alpha})|>\frac{\pi \alpha}{2}\) when \(|\operatorname{arg}(s)|>\frac{\pi}{2}\). From the proof of Theorem 3.2, we see that system (8) is asymptotically stable.

Second, suppose that the matrix \(C^{-1}(\rho C-I)\) is similar to a Jordan canonical form, i.e., there exists an invertible matrix P such that

Let \(J_{i},1\leq i \leq m\), have the form

The following proof is similar to case (ii) in Theorem 3.2 and will be omitted. The proof is completed. □

4 Illustrative examples

In this section, we present some examples to illustrate the application of our results.

Example 1

Consider the following system:

where \(E=\Bigl( {\scriptsize\begin{matrix}{} 1& 0 & -2\cr -1&0 &2 \cr 2&3&2 \end{matrix}} \Bigr), A=\Bigl( {\scriptsize\begin{matrix}{} 0& -1 & -2\cr 27&22 &17 \cr -18&-14&-10 \end{matrix}} \Bigr), x(t)=\Bigl( {\scriptsize\begin{matrix}{} x_{1}(t) \cr x_{2}(t) \cr x_{3}(t) \end{matrix}} \Bigr)\).

Since \(E-A\) is invertible, we have

\(\hat{E}^{d}=\Bigl( {\scriptsize\begin{matrix}{} -1& -\frac{41}{27} & -\frac{28}{27}\cr 2&\frac{77}{27}&\frac{46}{27} \cr -1&-\frac{34}{27}&-\frac{14}{27} \end{matrix}} \Bigr)\), and the initial condition \(x(0)\) satisfies

Hence, we get the explicit representation of the solution for the example:

Example 2

Consider the following system:

where \(E=\bigl ( {\scriptsize\begin{matrix}{} 1&0 \cr 0&0 \end{matrix}} \bigr ), A=\bigl ( {\scriptsize\begin{matrix}{} -1&0 \cr \frac{1}{3}&-1 \end{matrix}} \bigr ), x(t)=\bigl ( {\scriptsize\begin{matrix}{} x_{1}(t) \cr x_{2}(t) \end{matrix}} \bigr )\).

Since \(E-A\) is invertible, we have

and the initial condition \(x(0)\) satisfies

The eigenvalues of the matrix \(\hat{E}^{d}\hat{A}\) are \(\lambda _{1}=-1,\lambda_{2}=0\), therefore the system is asymptotically stable.

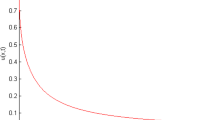

Verifying it in another way, the solution of the system is

From [16], when \(t\rightarrow+\infty\), there exists a constant \(M>1\), such that

When \(t\rightarrow+\infty\), we can get \(x_{1}(t)\rightarrow0\) and \(x_{2}(t)\rightarrow0\). Thus, the system (37) is asymptotically stable.

5 Conclusions

In this paper, we obtain the existence and uniqueness theorem for the initial value problem of the linear degenerate fractional differential system and derive an explicit representation of the solution for the system. The stability of linear degenerate fractional differential systems under the Riemann-Liouville derivative is investigated and some stability criteria for the system are given, which can be verified easily. We derive the relationship between the stability and the distribution of the zero eigenvalues of system as well as the distribution of the eigenvalues \(\lambda(E^{d}\hat{A})\) satisfying \(|\operatorname{arg}(\lambda(\hat{E}^{d}\hat{A}))|=\frac{\alpha\pi}{2}\). Since the considered systems are degenerate fractional systems, the theorems obtained in this paper can also be widely applied to many practical systems and generalize the results which are derived in [13, 37].

References

Miller, KS, Boss, B: An Introduction to the Fractional Calculus and Fractional Differential Equations. Wiley, New York (1993)

Samko, SG, Kilbas, AA, Marichev, OI: Fractional Integrals and Derivatives, Theory and Applications. Gordon & Breach, Yverdon (1993)

Podlubny, I: Fractional Differential Equations, vol. 198, pp. 30-34. Academic Press, San Diego (1999)

Kilbas, AA, Srivastava, HM, Trujillo, JJ: Theory and Applications of Fractional Differential Equations. Elsevier, Amsterdam (2006)

Shantanu, D: Functional Fractional Calculus for System Identification and Controls. Springer, Berlin (2008)

Lakshmikantham, V, Leela, S, Vasundhara Devi, J: Theory of Fractional Dynamic Systems. Cambridge Academic Publishers, Cambridge (2009)

Diethelm, K: The Analysis of Fractional Differential Equations. Springer, Heidelberg (2010)

Lakshmikantham, V, Vatsala, AS: Basic theory of fractional differential equations. Nonlinear Anal. 69, 2677-2682 (2008)

Lakshmikantham, V: Theory of fractional functional differential equations. Nonlinear Anal. 69, 3337-3343 (2008)

Matignon, D: Stability results for fractional differential equations with applications to control processing. In: Computational Engineering in Systems Applications. Multiconference, IMACS, IEEE-SMC, Lille, France, vol. 2, pp. 963-968 (1996)

Chen, YQ, Moore, KL: Analytical stability bound for a class of delayed fractional-order dynamic systems. Nonlinear Dyn. 29, 191-200 (2002)

Deng, WH, Li, C, Lu, J: Stability analysis of linear fractional differential system with multiple time delays. Nonlinear Dyn. 48, 409-416 (2007)

Odibat, ZM: Analytic study on linear systems of fractional differential equations. Comput. Math. Appl. 59, 1171-1183 (2010)

Qian, D, Li, C, Agarwal, RP, Wong, PJY: Stability analysis of fractional differential systems with Riemann-Liouville derivative. Math. Comput. Model. 52, 862-872 (2010)

Cermak, J, Kisela, T, Nechvatal, L: Stability regions for linear fractional differential systems and their discretizations. Appl. Math. Comput. 219, 7012-7022 (2013)

Sen, MD: About robust stability of Caputo linear fractional dynamic system with time delays through fixed point theory. Fixed Point Theory Appl. 2011, Article ID 867932 (2011)

Liu, KW, Jiang, W: Stability of fractional neutral systems. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2014, Article ID 78 (2014). doi:10.1186/1687-1847-2014-78

Zhang, FR, Li, CP: Stability analysis of fractional differential systems with order lying in \((1, 2)\). Adv. Differ. Equ. 2011, Article ID 213485 (2011). doi:10.1155/2011/213485

Chen, FL: A review of existence and stability results for discrete fractional equations. J. Comput. Complex. Appl. 1(1), 22-53 (2015)

Hu, JB, Zhao, LD: Stabilization and synchronization of fractional chaotic systems with delay via impulsive control. J. Comput. Complex. Appl. 2(3), 103-111 (2016)

Li, Y, Chen, Y, Podlubny, I: Mittag-Leffler stability of fractional order nonlinear dynamic systems. Automatica 45, 1965-1969 (2009)

Li, Y, Chen, Y, Pudlubny, I: Stability of fractional-order nonlinear dynamic systems: Lyapunov direct method and generalized Mittag-Leffler stability. Comput. Math. Appl. 59, 1810-1821 (2010)

Chen, F, Nieto, JJ, Zhou, Y: Global attractivity for nonlinear fractional differential equations. Nonlinear Anal., Real World Appl. 13, 287-298 (2012)

Zhou, XF, Hu, LG, Liu, S, Jiang, W: Stability criterion for a class of nonlinear fractional differential systems. Appl. Math. Lett. 28, 25-29 (2014)

Delavari, H, Baleanu, D, Sadati, J: Stability analysis of Caputo fractional-order nonlinear systems revisited. Nonlinear Dyn. 67, 2433-2439 (2012)

Wang, JR, Lv, LL, Zhou, Y: New concepts and results in stability of fractional differential equations. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 17, 2530-2538 (2012)

Chen, LP, He, YG, Chai, Y, Wu, RC: New results on stability and stabilization of a class of nonlinear fractional-order systems. Nonlinear Dyn. 75, 633-641 (2014)

Wen, YH, Zhou, XF, Zhang, ZX, Liu, S: Lyapunov method for nonlinear fractional differential systems with delay. Nonlinear Dyn. 82, 1015-1025 (2015)

Kunkel, P, Mehrmann, V: Differential Algebraic Equations. European Mathematical Society, Zürich (2006)

Dai, L: Singular Control Systems. Springer, Berlin (1989)

Campbell, SL: Singular Systems of Differential Equations, pp. 32-36. Pitman, London (1980)

Campbell, SL, Linh, VH: Stability criteria for differential-algebraic equations with multiple delays and their numerical solutions. Appl. Math. Comput. 208, 397-415 (2009)

Chyan, CJ, Du, NH, Linh, VH: On data-dependence of exponential stability and stability radii for linear time-varying differential-algebraic systems. J. Differ. Equ. 245, 2078-2102 (2008)

Jiang, W: The constant variation formulae for singular fractional differential systems with delay. Comput. Math. Appl. 59(3), 1184-1190 (2010)

Zhang, ZX, Jiang, W: Some results of the degenerate fractional differential system with delay. Comput. Math. Appl. 62(3), 1284-1291 (2011)

N’Doye, I, Darouach, M, Zasadzinski, M, Radhy, NE: Robust stabilization of uncertain descriptor fractional-order systems. Automatica 49, 1907-1913 (2013)

Bonilla, B, Rivero, M, Trujillo, JJ: On systems of linear fractional differential equations with constant coefficients. Appl. Math. Comput. 187, 68-78 (2007)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the anonymous referees and the editor for many friendly and helpful suggestions, which led to great deal of improvement of the original manuscript. The work of Z Zhang was partly supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China under Grants 11371027, 11071001 and 11201248, the program of Natural Science Research in Anhui Universities under Grants KJ2011A020 and KJ2013A032, the Foundation for Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China under Grant 20123401120001, the Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation under Grant 1608085MA12, 1208085MA13, the Scientific Research Starting Fund for Dr. of Anhui University under Grant 023033190142 and the Young Outstanding Teacher Overseas Training Program of Anhui University. The work of J Liu was partly supported by the Natural Science Foundation for the Higher Education Institutions of Anhui Province of China under Grant KJ2015A331 and the National Science Foundation of China under Grants 11601006, 11471016 and 11401004. The work of J Cao was partly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 61272530, the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province of China under Grant BK2012741, the Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education under Grants 20110092110017 and 20130092110017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

The authors have made equal contributions to each part of this paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z., Liu, JB., Cao, J. et al. Stability results for the linear degenerate fractional differential system. Adv Differ Equ 2016, 216 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-016-0941-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-016-0941-0