Abstract

Background

Dirofilariosis is an emerging vector-borne parasitic disease in Europe. Monitoring of wild and domestic carnivores demonstrated circulation of Dirofilaria spp. in Romania in the past. For the implementation of control measures, knowledge on the native mosquito community responsible for Dirofilaria spp. transmission is required.

Methods

Mosquito samples originated from a longitudinal study previously performed in the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve. Mosquito pools were screened for Dirofilaria immitis and Dirofilaria repens. The samples comprised 240,572 female mosquito specimens collected every ten days between April and September in 2014 at four different trapping sites. In addition, blood samples of 36 randomly selected dogs were collected in 2016 in each of the four mosquito sampling sites. A duplex real-time assay was used to detect the presence of one or both Dirofilaria species for each sample. This assay targets the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 and the 16S rRNA gene fragments to differentiate both parasites.

Results

Dirofilaria immitis and D. repens were detected in mosquito pools at all four trapping sites. In the 2118 mosquito pools tested, D. immitis was identified for eight and D. repens for six of the 14 screened mosquito taxa, with a higher prevalence of D. immitis (4.53% of analysed pools) compared to D. repens (1.09%). Dirofilaria spp. were also identified in dogs from the same sampling sites with a prevalence of 30.56%. For both Dirofilaria species, the highest estimated infection rates (EIRs) were found in Anopheles maculipennis (s.l.) (D. immitis: EIR = 0.206 per 100 specimens, D. repens: EIR = 0.066 per 100 specimens). In contrast, Coquillettidia richiardii and Anopheles hyrcanus as the most frequent taxa had infection rates which were significantly lower: Cq. richiardii (D. immitis: EIR = 0.021; D. repens: EIR = 0.004); An. hyrcanus (D. immitis: EIR = 0.028; D. repens: EIR = 0.006). The number of positive pools per calendar week was positively correlated with the number of screened pools per calendar week, suggesting constant Dirofilaria spp. transmission during the observation period.

Conclusions

This study further confirms significant circulation of Dirofilaria spp. in eastern Europe, with high parasite prevalence in domestic canids and mosquitoes. Therefore, systematic monitoring studies are required to better understand the environmental risk factors for Dirofilaria transmission, allowing the implementation of effective surveillance and control measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Dirofilaria repens and Dirofilaria immitis are the causal agents of dirofilariosis in Europe [1]. Both vector-borne filarioid species (Nematoda: Onchocercidae) share the same transmission cycle, consisting of different mosquito species as intermediate hosts and canids as the predominant definitive hosts. The infection of pulmonary arteries and right heart chambers by D. immitis can cause severe conditions in dogs (heartworm disease) [2]. In contrast, D. repens in dogs are mainly detected in subcutaneous tissues with considerably milder symptoms (subcutaneous dirofilariosis). Other mammalian species, including humans, are aberrant hosts, in which the parasites’ fitness is reduced, resulting in the production of no or significantly fewer microfilariae [3]. Nevertheless, Dirofilaria spp. infections in humans can result in different symptoms. This predominantly includes local swelling caused by migration of the worm in the subcutaneous skin. However, in rare cases, there have been even reports of severe clinical manifestations including meningoencephalitis [4].

Human and canine dirofilariosis are considered emerging vector-borne parasitic diseases in Europe [2]. For decades, infections were predominantly restricted to Mediterranean regions and the eastern bounds of the continent. However, recent reports indicated a noticeable spread of the disease towards Central Europe. At the same time, an increasing numbers of human cases were reported for countries previously known for Dirofilaria spp. circulation (e.g. Ukraine [5], Bulgaria [6] and Belarus [7]).

Dirofilaria spp. were recognized in Romania at least a decade ago [8]. Different studies on the parasites’ prevalence in dogs detected local infection rates between 3% and even more than 60% [8,9,10,11,12,13]. In addition to domestic animals, recent studies also identified D. immitis or D. repens in different wild carnivore species (golden jackals, red fox, wildcat, grey wolf, least weasel), which probably have critical roles as reservoirs maintaining the helminths in natural disease foci [14, 15]. Nevertheless, only a few human cases have been identified in the country so far [16, 17]. A similar observation, i.e. high frequency of Dirofilaria spp. infections in carnivores in combination with low prevalence in humans, was also observed for other countries in eastern Europe (e.g. Belarus), which might be explained by a relative low awareness of physicians [7].

Nevertheless, although studies on vertebrate hosts have given clear indications for the autochthonous transmission of Dirofilaria spp. in Romania, there is a lack of knowledge regarding the native mosquito vectors. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, only one xenomonitoring study has been conducted so far. Ionică et al. [18] collected a relative small number of mosquitoes (~6000 specimens) in the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve (DDBR). All samples of randomly collected mosquitoes were negative for filarioid DNA. Only a single Aedes vexans specimen was positive for D. repens trapped near a microfilaremic dog. The animal was co-infected with D. immitis and D. repens. However, as mentioned by the authors, the study results are not representative, as only a small number of specimens were collected on four days in July 2015.

Therefore, in order to get a comprehensive overview on the potential vectors of Dirofilaria spp., mosquito samples from a previous published longitudinal study in the DDBR [19] were screened for D. immitis and D. repens DNA. Lakes and channels in the area form a diverse mosaic of natural marshes. These provide highly diverse and productive breeding sites for mosquitoes. The samples from four trapping sites collected every ten days between April and September in the year 2014 comprise 240,572 female mosquito specimens (14 taxa in 8 genera), representing 24.14% of the 58 currently known mosquito species of Romania [19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. The screening results were used to identify potential mosquito vectors of Dirofilaria spp. in Romania and to better understand the temporal risk of transmission. Furthermore, after the detection of positive mosquito pools for 2014, blood samples of randomly selected dogs collected in each of the four mosquito sampling sites in 2016 were screened for Dirofilaria spp. DNA to evaluate the local prevalence of both filarioids in the definitive host.

Methods

Details regarding the sampling methods, sampling sites and morphological mosquito identification were previously described [19]. The Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve Authority issued the research permits and corresponding approvals (9/25.04.2014, 10692/ARBDD/25.04.2014; 7717/ARBDD/28.04.2016, 11/28.04.2016). Mosquitoes were pooled per mosquito taxon, date and sampling site. This resulted in pools between 1 and 250 specimens at the maximum (mean = 113.58).

In addition, at the end of September/beginning of October in 2016, 36 dogs were sampled at the 4 mosquito sampling sites (2–15 dogs per site). These were very isolated and characterized by a few people with a small number of owned dogs. All locally available dogs allowing blood sampling with the assistance of the owner were sampled. The animals did not show any clinical symptoms. Blood samples from the cephalic vein of domestic dogs were collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid at each of the four mosquito sampling sites and transported to the laboratory on dry ice. DNA of mosquito pools and single dog samples were extracted with a KingFisher™ Flex Magnetic Particle Processor using MagMAX™ Pathogen ribonucleic acid/DNA Kit (both Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The samples were screened with the previously described duplex real-time PCR assay to detect D. repens and D. immitis [7, 26]. This assay targets the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 and the nuclear 16S rRNA gene fragment to differentiate both parasites. It is important to note that the number of sampled mosquitoes was very high, resulting in relatively huge pool sizes. This might result in reduced sensitivity of the real-time PCR, i.e. false negative results.

The program R [27] with four different packages was used for all analyses. ggplot2 [28], tidyr [29] and plyr [30] were used to analyse and visualize the results. The functions of the package binGroup [31] were applied to calculate estimated infection rates (EIRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) per vector species and Dirofilaria species. Biased-corrected maximum likelihood estimation was used for point estimates and skewness-correction for 95% CIs. Significant differences were apparent from non-overlapping 95% CIs.

Results

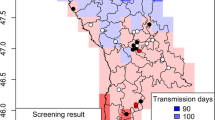

Mosquito pools from 14 mosquito taxa in six different genera (Uranotaenia, Culiseta, Culex, Coquillettidia, Anopheles and Aedes) were screened for Dirofilaria spp. using a real-time duplex PCR (Table 1). From the 240,572 specimens, Coquillettidia richiardii (40.85%) and Anopheles hyrcanus (34.12%) were most frequent, followed by five species each between 3 and 8% of all mosquito specimens: Culex pipiens (s.l.)/Culex torrentium, Aedes caspius, Culex modestus, Anopheles maculipennis (s.l.) and Ae. vexans. Out of 2118 mosquito pools screened, 96 pools (4.53%) tested positive for Dirofilaria spp. DNA (EIR per 100 specimens = 0.041, 95% CI: 0.034–0.050), which further divided into 83 pools (3.92%) positive for D. immitis (EIR = 0.036, 95% CI: 0.029–0.044) and 23 pools (1.09%) positive for D. repens (EIR = 0.010, 95% CI: 0.006–0.014). In total, 10 pools (0.47%) were tested positive for both Dirofilaria species representing 10.42% of all pools tested positive for Dirofilaria spp. DNA. Thereby, the number of positive pools per calendar week was statistically significantly positively correlated with the number of screened pools per calendar week (rS = 0.74, P < 0.001; Fig. 1).

Dirofilaria immitis was detected for eight and D. repens for six of the 14 screened mosquito taxa (Table 1). From all mosquito species collected with more than 50 specimens, only Cx. modestus, represented by more than 9000 specimens, was negative for Dirofilaria spp. DNA. The number of screened specimens per taxon was positively correlated with the number of analyzed specimens per taxon (rS = 0.85, P < 0.001).

For the mosquito species with larger sample sizes (> 5000 specimens), allowing the calculation of reliable infection rates [32], An. maculipennis (s.l.) had highest rates of infection for both Dirofilaria species (D. immitis: EIR = 0.206, 95% CI: 0.125–0.325; D. repens: EIR = 0.066, 95% CI: 0.027–0.137). Non-overlapping confidence intervals indicate statistically significantly lower EIRs for the two most frequent mosquito taxa Cq. richiardii (D. immitis: EIR = 0.021, 95% CI: 0.013–0.032; D. repens: EIR = 0.004, 95% CI: 0.001–0.010) and An. hyrcanus (D. immitis: EIR = 0.028, 95% CI: 0.018–0.041; D. repens: EIR = 0.006, 95% CI: 0.002–0.014).

Between 2.85 and 5.49% of the tested mosquito pools per trapping site were positive for Dirofilaria spp. DNA (Table 2). Dirofilaria immitis was more prevalent than D. repens for all four sites. These mosquito screening results are also reflected in the analysis of domestic canids. At each of the four sites, dogs were tested positive for Dirofilaria spp. DNA (30.56% of all 36 screened specimens). Thereby, the proportion of positive dogs per site ranged from 20.00 to 50.00%. Both filarioid species had similar prevalence (D. immitis: 7 dogs, 19.44%, D. repens: 8 dogs, 22.22%), with a high proportion of co-infections (4 dogs, 36.66% of Dirofilaria spp. positive specimens).

Discussion

The circulation of Dirofilaria spp. in Romania has been known for several years, but was primarily demonstrated through monitoring of domestic and wild carnivores [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. In contrast, information regarding the potential mosquito vectors was scarce [18]. Due to transportation problems, the lack of knowledge in particular applies to the DDBR [19]. Huge areas of the biosphere reserve are only reachable by boat. Results of the presented study confirm the local circulation of D. immitis and D. repens for all four sampling sites. Dirofilaria spp. DNA was detected in eight of the 14 analyzed mosquito species, indicating that 13.79% of the 58 currently known mosquito species of the country [19,20,21,22,23,24,25] have to be considered as potential vectors. This observation supports the assumption that a broad spectrum of mosquito taxa is potentially involved in the transmission cycles of Dirofilaria spp. in Europe with more than 20 species found infected so far [7, 18, 26, 33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48].

All mosquito species positive for Dirofilaria spp. DNA in the DDBR were classified as suspected vectors in at least one European xenomonitoring study [7, 26, 33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48], including Ae. vexans determined as potential vector in Romania before [18]. The number of positive pools per mosquito taxon was statistically positively correlated with the number of screened pools. Except for Cx. modestus, at least one pool of all mosquito species collected with more than 50 specimens was detected positive for one or both Dirofilaria species. More than 9000 Cx. modestus specimens were tested, but none of the pools were positive. However, the species was only identified as a potential vector in two European countries, Hungary [33, 38] and Moldova [26], which might allow the conclusion that the species is not the most important vector for Dirofilaria spp. in Europe.

In contrast, the analysis of a wide range of mosquito species again underlines the relevance of An. maculipennis (s.l.) in the local transmission cycles of dirofilariosis. Although trapped ten times less compared to the two most abundant species (Cq. richiardii, An. hyrcanus), this species had statistically significant higher infection rates. A similar observation was reported for Moldova [26]. In addition, positive pools of An. maculipennis (s.l.) were detected in Hungary [33], Italy [37], Austria [44], Germany [42, 46], Portugal [34] and Moldova [26], further underlying the relevance of An. maculipennis (s.l.) as vector of Dirofilaria species in Europe. This can partly be explained by the host-feeding patterns of the species, considered as a predominantly mammalophilic behavior [49, 50]. However, this also applies to other screened mosquito taxa (e.g. Cq. richiardii). Nevertheless, vector competence for Dirofilaria spp. is species-specific and can be affected by different factors. This includes the encapsulation/melanization of the parasite [51] or the increase of mosquito mortality linked to invasion of cells belonging to the Malphigian tubule [47, 52, 53]. Therefore, further vector competence studies are required to experimentally evaluate, which mosquito species are susceptible for Dirofilaia spp. infections [52, 54, 55].

The prevalence of Dirofilaria spp. in mosquitoes was positively correlated with the phenology of mosquitoes. A similar pattern was observed in Italy [47, 56] and Moldova [26], while no variation in the Dirofilaria spp. infection throughout the year in Portugal [34] and another study in Italy [35] has been observed. As previously discussed [26, 47, 57], the local risk for the transmission of Dirofilaria spp. is probably primarily driven by the abundance of the vector species and the presence of infected dogs.

Although the overall number of analyzed dog specimens was relative low (n = 36), infection rates between 20–50% indicate a high prevalence of Dirofilaria spp. in the four studied sites in the DDBR. Similar high values were found in several other studies in Romania [8,9,10,11,12,13]. Furthermore, there was a remarkably high proportion of co-infected dogs with more than 30% of all Dirofilaria spp. positive dogs infected with both helminths, D. immitis and D. repens. The finding is in agreement with a previous study from Romania, in which one quarter of all tested dogs were found to be infected with both Dirofilaria species [12]. This was also reflected in the screening results of mosquitoes from the same sampling sites. Although it cannot be ruled out that some of the detected co-infections in the mosquito pools are the result of different mosquito specimens infected with one or the other Dirofilaria species, the simultaneous detection of both parasite species in a high proportion of Dirofilaria spp. positive pools (10.42%) indicate a high probability of co-infected specimens. However, further studies are required to understand the risk of microfilaria transmission through these mosquitoes. The differences in the ecology of both Dirofilaria species within the mosquitoes as intermediate hosts are quite unknown. This includes potential competition, host specificity or general requirements for successful development [26].

Conclusions

Recent studies on the circulation of Dirofilaria spp. in different eastern European countries highlight significant local circulation with a wide range of mosquito species involved as vectors (e.g. Belarus [7] and Moldova [26]). These findings are confirmed in the here presented results for the DDBR (Romania), identifying a high prevalence of Dirofilaria spp. in domestic dogs and several potential mosquito vector species. Further systematic monitoring studies including different components of the Dirofilaria spp. transmission cycle (mosquito vectors, dogs as definitive and humans as secondary hosts) should be implemented in eastern European countries to evaluate the local risk of human and canine dirofilariosis, allowing the implementation of effective surveillance and control measures.

Abbreviations

- DDBR:

-

Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve

- DNA:

-

deoxyribonucleic acid

- EIR:

-

estimated infection rates

- PCR:

-

polymerase chain reaction

- RNA:

-

ribonucleic acid

References

Simon F, Siles-Lucas M, Morchon R, Gonzalez-Miguel J, Mellado I, Carreton E, et al. Human and animal dirofilariasis: the emergence of a zoonotic mosaic. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:507–44.

Otranto D, Dantas-Torres F, Brianti E, Traversa D, Petrić D, Genchi C, et al. Vector-borne helminths of dogs and humans in Europe. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:16.

Pampiglione S, Rivasi F. Human dirofilariasis due to Dirofilaria (Nochtiella) repens: an update of world literature from 1995 to 2000. Parassitologia. 2000;42:231–54.

Poppert S, Hodapp M, Krueger A, Hegasy G, Niesen WD, Kern WV, et al. Dirofilaria repens infection and concomitant meningoencephalitis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1844–6.

Salamatin RV, Pavlikovska TM, Sagach OS, Nikolayenko SM, Kornyushin VV, Kharchenko VO, et al. Human dirofilariasis due to Dirofilaria repens in Ukraine, an emergent zoonosis: epidemiological report of 1465 cases. Acta Parasitol. 2013;58:592–8.

Harizanov RN, Jordanova DP, Bikov IS. Some aspects of the epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of human dirofilariasis caused by Dirofilaria repens. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:1571–9.

Șuleșco T, Volkova T, Yashkova S, Tomazatos A, von Thien H, Lühken R, et al. Detection of Dirofilaria repens and Dirofilaria immitis DNA in mosquitoes from Belarus. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:3535–41.

Coman S, Bacescu B, Coman T, Parvu G, Dinu C, Petrut T, et al. Epidemiological and paraclinical aspects of canine dirofiloariosis. Lucr Stiinłifice Med Vet. 2007;40:333–9.

Ciocan R, Dărăbuş G, Igna V. Morphometric study of microfilariae of Dirofilaria spp. on dogs. Bull UASVM Vet Med. 2010;67:45–9.

Ciocan R, Mederle N, Jacsó O, Tánczos B, Fok É. Autochthonous cases of Dirofilaria in dogs from Timiș county (western part) Romania. Glob J Med Res. 2013;13:29–34.

Mircean V, Dumitrache MO, Gyorke A, Pantchev N, Jodies R, Mihalca AD, et al. Seroprevalence and geographic distribution of Dirofilaria immitis and tick-borne infections (Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, and Ehrlichia canis) in dogs from Romania. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012;12:595–604.

Ionica AM, Matei IA, Mircean V, Dumitrache MO, D’Amico G, Gyorke A, et al. Current surveys on the prevalence and distribution of Dirofilaria spp. and Acanthocheilonema reconditum infections in dogs in Romania. Parasitol Res. 2015;114:975–82.

Ciucă L, Musella V, Miron LD, Maurelli MP, Cringoli G, Bosco A, et al. Geographic distribution of canine heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis) infection in stray dogs of eastern Romania. Geospatial Health. 2016;11:499.

Ionica AM, Matei IA, D’Amico G, Daskalaki AA, Jurankova J, Ionescu DT, et al. Role of golden jackals (Canis aureus) as natural reservoirs of Dirofilaria spp. in Romania. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:240.

Ionică AM, Matei IA, D’Amico G, Ababii J, Daskalaki AA, Sándor AD, et al. Filarioid infections in wild carnivores: a multispecies survey in Romania. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:332.

Manescu R, Barascu D, Mocanu C, Pirvanescu H, Mindria I, Balasoiu M, et al. Subconjunctival nodule with Dirofilaria repens. Chir Buchar Rom 1990. 2009;104:95–7. (In Romanian)

Popescu I, Tudose I, Racz P, Muntau B, Giurcaneanu C, Poppert S. Human Dirofilaria repens infection in Romania: a case report. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2012;2012:472976.

Ionică AM, Zittra C, Wimmer V, Leitner N, Votýpka J, Modrý D, et al. Mosquitoes in the Danube Delta: searching for vectors of filarioid helminths and avian malaria. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:324.

Török E, Tomazatos A, Cadar D, Horváth C, Keresztes L, Jansen S, et al. Pilot longitudinal mosquito surveillance study in the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve and the first reports of Anopheles algeriensis Theobald, 1903 and Aedes hungaricus Mihályi, 1955 for Romania. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:196.

Prioteasa F-L, Falcuta E. An annotated checklist of the mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) of the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve. Eur Mosq Bull. 2010;28:240–5.

Prioteasa LF, Dinu S, Falcuta E, Ceianu CS. Established population of the invasive mosquito species Aedes albopictus in Romania, 2012–14. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2015;31:177–81.

Nicolescu G, Vladimirescu A, Ciolpan O. The distribution of mosquitoes in Romania (Diptera: Culicidae). Part I: Anopheles, Aedes and Culex. Eur Mosq Bull. 2002;13:17–26.

Nicolescu G, Vladimirescu A, Ciolpan O. The distribution of mosquitoes in Romania (Diptera: Culicidae). Part II: Culiseta, Coquillettidia, Ochlerotatus, Orthopodomyia and Uranotaenia. Eur Mosq Bull. 2003;14:1–15.

Nicolescu G, Vladimirescu A, Ciolpan O. The distribution of mosquitoes in Romania (Diptera: Culicidae). Part III: Detailed maps for Anopheles, Aedes and Culex. Eur Mosq Bull. 2003;14:25–31.

Nicolescu G, Vladimirescu A, Ciolpan O. The distribution of mosquitoes in Romania (Dipera: Culicidae). Part IV: Detailed maps for Coquillettidia, Culiseta, Ochlerotatus, Orthopodomyia and Uranotaenia. Eur Mosq Bull. 2003;15:16–27.

Șuleșco T, von Thien H, Toderaș L, Toderaș I, Lühken R, Tannich E. Circulation of Dirofilaria repens and Dirofilaria immitis in Moldova. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:627.

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2016.

Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. New York: Springer; 2009.

Wickham H, Henry L. tidyr: easily tidy data with “spread()” and “gather()” functions. 2017. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tidyr.

Wickham H. The split-apply-combine strategy for data analysis. J Stat Softw. 2011;40:1–29.

Zhang B, Bilder C, Biggerstaff B, Schaarschmidt F. binGroup: Evaluation and experimental design for binomial group testing. 2012. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=binGroup.

Walter SD, Hildreth SW, Beaty BJ. Estimation of infection rates in populations of organisms using pools of variable size. Am J Epidemiol. 1980;112:124–8.

Kemenesi G, Kurucz K, Kepner A, Dallos B, Oldal M, Herczeg R, et al. Circulation of Dirofilaria repens, Setaria tundra, and Onchocercidae species in Hungary during the period 2011–2013. Vet Parasitol. 2015;214:108–13.

Ferreira CAC, de Pinho Mixao V, Novo MTLM, Calado MMP, Goncalves LAP, Belo SMD, et al. First molecular identification of mosquito vectors of Dirofilaria immitis in continental Portugal. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:139.

Latrofa MS, Montarsi F, Ciocchetta S, Annoscia G, Dantas-Torres F, Ravagnan S, et al. Molecular xenomonitoring of Dirofilaria immitis and Dirofilaria repens in mosquitoes from north-eastern Italy by real-time PCR coupled with melting curve analysis. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:76.

Bocková E, Iglódyová A, Kočišová A. Potential mosquito (Diptera:Culicidae) vector of Dirofilaria repens and Dirofilaria immitis in urban areas of eastern Slovakia. Parasitol Res. 2015;114:4487–92.

Cancrini G, Magi M, Gabrielli S, Arispici M, Tolari F, Dell’Omodarme M, et al. Natural vectors of dirofilariasis in rural and urban areas of the Tuscan region, central Italy. J Med Entomol. 2006;43:574–9.

Zittra C, Kocziha Z, Pinnyei S, Harl J, Kieser K, Laciny A, et al. Screening blood-fed mosquitoes for the diagnosis of filarioid helminths and avian malaria. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:16.

Bocková E, Rudolf I, Kočišová A, Betášová L, Venclíková K, Mendel J, et al. Dirofilaria repens microfilariae in Aedes vexans mosquitoes in Slovakia. Parasitol Res. 2013;112:3465–70.

Bravo-Barriga D, Parreira R, Almeida APG, Calado M, Blanco-Ciudad J, Serrano-Aguilera FJ, et al. Culex pipiens as a potential vector for transmission of Dirofilaria immitis and other unclassified Filarioidea in Southwest Spain. Vet Parasitol. 2016;223:173–80.

Kurucz K, Kepner A, Krtinic B, Zana B, Földes F, Bányai K, et al. First molecular identification of Dirofilaria spp. (Onchocercidae) in mosquitoes from Serbia. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:3257–60.

Kronefeld M, Kampen H, Sassnau R, Werner D. Molecular detection of Dirofilaria immitis, Dirofilaria repens and Setaria tundra in mosquitoes from Germany. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:30.

Rudolf I, Šebesta O, Mendel J, Betášová L, Bocková E, Jedličková P, et al. Zoonotic Dirofilaria repens (Nematoda: Filarioidea) in Aedes vexans mosquitoes, Czech Republic. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:4663–7.

Silbermayr K, Eigner B, Joachim A, Duscher GG, Seidel B, Allerberger F, et al. Autochthonous Dirofilaria repens in Austria. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:226.

Yildirim A, Inci A, Duzlu O, Biskin Z, Ica A, Sahin I. Aedes vexans and Culex pipiens as the potential vectors of Dirofilaria immitis in central Turkey. Vet Parasitol. 2011;178:143–7.

Czajka C, Becker N, Jöst H, Poppert S, Schmidt-Chanasit J, Krüger A, et al. Stable transmission of Dirofilaria repens nematodes, northern Germany. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:328–30.

Capelli G, Frangipane di Regalbono A, Simonato G, Cassini R, Cazzin S, Cancrini G, et al. Risk of canine and human exposure to Dirofilaria immitis infected mosquitoes in endemic areas of Italy. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:60.

Cancrini G, Scaramozzino P, Gabrielli S, Di Paolo M, Toma L, Romi R. Aedes albopictus and Culex pipiens implicated as natural vectors of Dirofilaria repens in central Italy. J Med Entomol. 2007;44:1064–6.

Börstler J, Jöst H, Garms R, Krüger A, Tannich E, Becker N, et al. Host-feeding patterns of mosquito species in Germany. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:318.

Schönenberger AC, Wagner S, Tuten HC, Schaffner F, Torgerson P, Furrer S, et al. Host preferences in host-seeking and blood-fed mosquitoes in Switzerland. Med Vet Entomol. 2015;30:39–52.

Zielke E. Schutzmechanismen von Culiciden gegenüber Infestationen mit Filarien. Mitt Österr Ges Tropenmed Parasitol. 1993;15:149–56.

Lai CH, Tung KC, Ooi HK, Wang JS. Competence of Aedes albopictus and Culex quinquefasciatus as vector of Dirofilaria immitis after blood meal with different microfilarial density. Vet Parasitol. 2000;90:231–7.

Serrao ML, Labarthe N, Lourenco-de-Oliveira R. Vectorial competence of Aedes aegypti (Linnaeus 1762) Rio de Janeiro strain to Dirofilaria immitis (Leidy 1856). Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2001;96:593–8.

Montarsi F, Ciocchetta S, Devine G, Ravagnan S, Mutinelli F, Frangipane di Regalbono A, et al. Development of Dirofilaria immitis within the mosquito Aedes (Finlaya) koreicus, a new invasive species for Europe. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:177.

Silaghi C, Beck R, Capelli G, Montarsi F, Mathis A. Development of Dirofilaria immitis and Dirofilaria repens in Aedes japonicus and Aedes geniculatus. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:94.

Capelli G, Poglayen G, Bertotti F, Giupponi S, Martini M. The host-parasite relationship in canine heartworm infection in a hyperendemic area of Italy. Vet Res Commun. 1996;20:320–30.

Montoya-Alonso JA, Mellado I, Carreton E, Cabrera-Pedrero ED, Morchon R, Simon F. Canine dirofilariosis caused by Dirofilaria immitis is a risk factor for the human population on the island of Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, Spain. Parasitol Res. 2010;107:1265–9.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant of the Romanian Ministry of National Education, CNCS-UEFISCDI, PN-II-ID-2012-4-0595 and the Sectoral Operational Programme Human Resources Development, financed from the European Social Fund and by the Romanian Government under POSDRU/187/1.5/S/156069/.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the study: DC, LK, MS, SJ, HJ, JSC, Eta and RL. Collected the data: AT, ETö, IM, CH, SJ and HJ. Analysed the data: RL. Drafted the manuscript: RL and ETa. Critically revised the manuscript: DC. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tomazatos, A., Cadar, D., Török, E. et al. Circulation of Dirofilaria immitis and Dirofilaria repens in the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve, Romania. Parasites Vectors 11, 392 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-018-2980-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-018-2980-8