Abstract

Background

Over the recent decades, container-breeding mosquito species belonging to the genus Aedes have frequently been recorded far from their place of origin. Aedes koreicus was first reported in north-eastern Italy in 2011, in a region endemic for Dirofilaria immitis, the agent of canine heartworm disease. The vector competence of Ae. koreicus for D. immitis was here tested under laboratory conditions, by infecting mosquitoes with a local strain of D. immitis.

Methods

Blood containing 3000 microfilariae/ml was offered to 54 mosquitoes (T group) while 29 were left as a control (C group). Mosquitoes killed at scheduled days post infection (dpi) and naturally dead were divided in head, thorax and abdomen and examined for D. immitis larval stages by dissection under a microscope and molecularly.

Results

Of the 45 engorged mosquitoes in T, 32 (71.1%) scored positive for D. immitis larval stages. L3 were found as early as 8 dpi in the Malpighian tubules and then in the thorax, salivary glands, palp and proboscis. At the end of the study a total of 18 mosquitoes developed L3 giving an estimated infection rate at 12 dpi of 68.2% and a vector efficiency index of 25.2%. The rate of mortality in T group within the first 9 days post infection was significantly higher in T group (47.6%) than in C group (8.3%) (p < 0.01). The concordance between microscopy and PCR was high (0.8-0.9), however, a positivity for D. immitis in the head was found molecularly at 13 dpi, three days before microscopy.

Conclusions

Aedes koreicus, a new invasive species for Europe, is most likely a competent vector of D. immitis being of potential relevance in the natural cycle of the parasite. This poses a new threat for animal and human health in endemic areas for dirofilariosis and enhances the risk of spreading the infection in previously non-endemic areas. These results stress the importance of active surveillance and control strategies to minimize the risk of introduction of invasive alien species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Over the recent decades, container-breeding mosquito species belonging to the genus Aedes (Meigen) have frequently been recorded far from their place of origin [1]. Some invasive species of Aedes are capable of transmitting viral, bacterial or parasite pathogens of public health concern when they establish in previously non- endemic geographic areas [2,3]. A key example is the tiger mosquito Aedes albopictus (Skuse) (syn. Stegomyia albopicta) that was first imported to Italy in the early 1990s [4], being later responsible for an outbreak of chikungunya virus in 2007 [5].

The latest invasive container-breeding mosquito introduced in Europe was Aedes (Finlaya) koreicus (Edwards), a species native of Korea, China, Japan [6,7] and of the Asian part of Russia [8]. Since its first report in Belgium in 2008 [9], this mosquito has been identified in north-eastern Italy in 2011 [10] and in the south of European Russia in 2013 [11]. While in Belgium the mosquito is localized in a very restricted area of about 6 km2 [12], in Italy it has colonized more than 3000 km2 with an expanding trend [13].

Scientific information on the biology, ecology and vector competence of Ae. koreicus is lacking, and compounded by the fact that this mosquito species has long been misidentified as Aedes japonicus japonicus (Theobald), a species morphologically similar which lives in sympatry with the former [14].

The dog heartworm Dirofilaria immitis (Filarioidea, Onchocercidae), a filarial nematode primarily affecting dogs and less frequently cats and humans, is endemic in northern Italy, particularly along the Po River valley and the surrounding flat areas [15,16]. The prevalence of D. immitis in stray dogs living in the same geographical area where Ae. koreicus most likely established for the first time, has been reported as high as 67% [17]. Accordingly, recent surveys on mosquito species potential vectors of this filarioid (i.e., Culex pipiens L., Aedes (syn. Ochlerotatus) caspius (Pallas), Aedes vexans (Meigen)) demonstrated that infected mosquitoes are widespread all over the region [18] and that dogs and humans are most likely exposed to infected mosquitoes as often as every four nights and 14 nights, respectively [19]. Additionally, Ae. albopictus has been confirmed as a natural vector of dirofilariosis in Italy [20], whereas Ae. koreicus was found as a vector of D. immitis in a single laboratory trial carried out in Korea [21]. Nonetheless, in the latter study, a clear discrimination between Ae. koreicus and Ae. japonicus japonicus was not possible, since the two species were only clearly described in the 1950s [14].

Therefore, the vector competence of Ae. koreicus for D. immitis was here assessed under laboratory conditions, by infecting a mosquito colony derived from specimens collected from new geographic foci in north-eastern Italy, with a local strain of D. immitis from an autochthonously infected dog.

Methods

Aedes koreicus colony

The colony of Ae. koreicus originated from larvae collected from a field site (Province of Belluno, north-eastern Italy) where the presence of Ae. albopictus was not previously reported [13]. Larvae were kept in the same water as they were collected from until adult emergence. A subset (about 10% of the larvae and adults) were confirmed as Ae. koreicus by morphology and PCR as described elsewhere [10,22]. No other species were present. The colony was maintained in an insectarium under laboratory standard condition: temperature 25 ± 1°C; relative humidity 65 ± 5% and light–dark cycle of 16–8 hours. Mosquitoes were nourished with a 10% sucrose solution and fresh apple slices and, for reproduction, they were supplied with blood from cattle and poultry as described below for mosquito infection.

Dirofilaria immitis microfilariae

The positive and negative canine blood samples for microfilariae (mf) were selected by one of the authors (AFR) during routine diagnostic duties at the Laboratory of Parasitology, Padua University. The infected dog was a 14 year old mixed breed, living outdoors in a village in north-eastern Italy, with no history of travel outside its native village. The presence of D. immitis in blood samples was confirmed by filtration test [23], serology test (SNAP Heartworm RT Test©, IDEXX, Laboratories, Inc., USA) and a duplex real-time PCR, as described elsewhere [18]. Sequencing of the positive blood sample confirmed the presence of D. immitis but not of D. repens, also reported in the area [17,18]. The blood was also screened by PCRs for other pathogens transmitted by arthropods known to be endemic in north-eastern Italy [24], i.e. Leishmania infantum [25], Rickettsia spp. [26], Anaplasma phagocytophilum [27], candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis [28], Borrelia burgdorferi sl [29] and Babesia/Theileria species [30].

Microfilariae were counted by examining thick blood smears by microscopy: ten drops of 20 μl were placed onto glass slides with a cover glass and examined under a light microscope (40×). The average number of mf was estimated by assessing the mean values observed in the ten counts [31]. Approximately 3000 mf per ml of blood were estimated.

Aedes koreicus infection

Two experimental groups of mosquitoes were fed using blood with mf (n = 54; test group, T) or without mf (n = 29; control group, C), according to their availability. The mosquitoes were maintained in two cages measuring 50 cm per side for (T) and 30 cm per side for (C). The Density-Resting Surface (DRS) was calculated by dividing the vertical resting surface area of the cages (cm2) by the number of mosquitoes inside [32], being the final DRS values 185.2 in (T) and 124.1 in (C), corresponding to a low density. The mosquito population density into the cages was kept low to avoid mortality caused by crowding.

All mosquitoes were fed using an artificial feeding system (Hemotek® feeding system; Discovery Workshops, Lancashire, United Kingdom) [33] loaded with 5 ml of infected or negative blood with Na Citrate 9NC 3.8% anticoagulant solution in (T) and (C) group, respectively. The blood was provided for half an hour after which time unfed mosquitoes were removed from the cages. All bloodfed mosquitoes were provided with a 10% sucrose solution and fresh apple slices ad libitum.

Within 24 hours post- infection, three mosquito specimens were killed and dissected from (T) group to score the number of mf ingested. Mosquitoes were killed and examined at scheduled days (see Table 1). The mosquitoes were killed by putting them in dry ice and dissected in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) solution for the detection of D. immitis larvae under the stereomicroscope. All the mosquitoes naturally dead during the study were also examined. The head, the thorax and the abdomen of mosquitoes were examined on separate slides.

The larval developmental stages retrieved were identified, counted and, when possible, measured [34]. In addition five specimens, three from T group (two dead and one killed) and two from C group (one dead and one killed) were used for histological observations as described elsewhere [35,36].

After the microscopic observations, the head, thorax, and abdomen of each sample was recovered in PBS and a molecular analysis was performed to screen for the presence of D. immitis using a duplex real-time PCR [18].

Statistical analysis

The rate of mortality was calculated each day, within 9 dpi and at the end of the study (28 dpi) as the percentage of dead mosquitoes over the total engorged in each cage (n = 42, excluded the three mosquitoes sacrificed for the mf intake calculation). The significance of the difference in mortality rates in the two cages was tested using the Fischer’s Exact test.

The Infection Rate (IR) and the Vector Efficiency Index (VEI) were calculated for (T) group [37]. The IR is defined as the number of blood fed mosquitoes showing infective third stage larvae (L3) in their body multiplied by 100 and divided by the number of surviving mosquitoes at the end of the incubation period. The period of extrinsic incubation is the number of days required for the development of the first L3 and was set arbitrarily at 12 dpi to be comparable with other studies [37]. The VEI is defined as the average number of L3 developed in the mosquitoes from the dpi of the first recovered L3 to the end of the study, multiplied by 100 and divided by the average number of ingested mf. The VEI was here determined in the period 8–28 dpi. The concordance between the finding of mf and larval stages by microscopy and PCR was calculated using the k coefficient (Win Epi 2.0 software, available online at: http://www.winepi.net/uk/index.htm).

Results

After the blood meal, a similar percentage of mosquitoes were engorged in the two groups (i.e. 83.3% and 82.7% in T and C, respectively). The mean number of mf ingested per female in group T was 14.3 (range from 1 to 36).

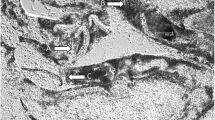

The number of mf and larvae found during the study in killed and naturally dead mosquitoes is reported in Table 1. The larvae were identified as first stage larvae (L1), typically sausage-like in shape, second (L2) and third (L3) stage larvae (Figure 1), being their morphological features consistent with those reported in the literature [34] (Table 2). Movies of the living larval stages are accessible in Additional files 1, 2 and 3.

Microfilariae were found in all the naturally dead mosquitoes until 6 dpi (Figure 2). L1, L2 and L3 were found in abdomen, whereas in the thorax and head only L3 were observed (Table 2). L1 were generally observed from 3 to 9 dpi with the exception of two L1 in a single mosquito at 24 dpi (Table 1). The number and the proportion of L1 were particularly high at 6 dpi (mean = 22.3; 97.1%), then rapidly declined due to development and mortality. Indeed L1 were found melanized and dead at 6 dpi (Figure 3). L2 (n = 8) were found only once in the Malpighian tubules of a mosquito at 13 dpi (Table 2, Figure 4). The first L3 were observed in the Malpighian tubules at 8 dpi (n = 15 in one mosquito) (Additional file 4) and, later on, from 16 through 28 dpi, they were also found in the thorax, salivary glands, palp and proboscis (Figure 5). In particular, L3 were observed emerging from the proboscis of three mosquitoes (Additional file 5). At the end of the study, 18 mosquitoes developed L3, giving an estimated IR of 68.2% and a VEI of 25.2%. The overall rate of mortality in mosquitoes was 78.6% (n = 33) and 25% (n = 6) in group T and C, respectively (p < 0.01), being higher during the first 9 dpi (i.e., 47.6% in group T vs 8.3% in group C; p < 0.01) (Figure 6).

Detection of D. immitis by molecular analysis showed a high but not complete agreement (k = 0.8-0.9) with microscopic identification, with PCR being slightly more sensitive than microscopy (Table 3). D. immitis was found in the head at 13 dpi by PCR, three days before it was observed by microscopy.

All the mosquitoes tested by histology showed no larvae or evidence of alterations in their body.

Discussion

Despite the fact that the experiment was not repeated due to the limited availability of mosquitoes, the finding of L3 emerging from the proboscis clearly indicated that D. immitis infective larvae developed in this mosquito species. Further experimental evidence of L3 transmission to a host is necessary for a final confirmation of the role Ae. koreicus plays as intermediate host for D. immitis.

The larval development to the infective third stage in other vectors of D. immitis (e.g. Culex, Aedes, Ochlerotatus and Anopheles) depends on several factors [34,38]. The ability of an invertebrate host to survive mf invasion and consequent development is pivotal for assessing its vector competence. Indeed, soon after ingestion, mf pass through the mosquito pharynx reaching the midgut. In about 24 hours they migrate to the Malpighian tubules where they develop into L1, L2 and finally L3 stages, eventually emerging from the tubules and migrating through the thorax to the salivary glands and the proboscis [38-41]. Accordingly, the critical period for the survival of Ae. koreicus (i.e. the higher rate of mortality) was during the first 4 dpi and around 8–9 dpi, corresponding to the invasion of the Malpighian cells by mf and to the emergence of L3 from the tubules, respectively.

Furthermore, the rate of survival of mosquitoes infected with D. immitis may be affected by the number of mf ingested, with high microfilaraemia causing fatal injuries leading to mortality [39,42,43]. The high overall rate of mortality of Ae. koreicus herein recorded (78.6%) is likely affected by the length of the study. Indeed, the rate of mortality within the first 9 dpi (47.6%) was similar to that of other studies carried out for Ae. aegypti (48.1%; 9 dpi) and for different strains of Ae. albopictus (32.9-54%; 15 dpi), where mosquitoes were experimentally administered with a comparable number of mf (i.e., 3000–3300 mf/ml) [43,44]. Accordingly, if Ae. koreicus is able to support the development of infective L3 at higher levels of microfilaraemia remains to be demonstrated, since dogs harboring high (35,000 mf/ml) to very high (>70,000 mf/ml) numbers of mf may be a frequent occurrence in geographical areas endemic for canine heartworm disease [17,19,45].

In our study the observation of melanized L1 only once within 6 dpi suggests that the majority of them were not destroyed. Previous studies on Ae. albopictus infected with D. immitis reported the arrest of the development of L1 and L2 stages, i.e. melanization and degeneration of larvae in the Malpighian tubules [44,46,47], or the arrest of the development at the mf stage in Ae. aegypti, [38,48,49]. In Ae. koreicus Feng [21] observed degenerated larvae at different stages but especially as mf.

Importantly, artificial blood-feeding, incorporating anticoagulants, might increase the rate of mf migration, because blood clotting in the midgut has been found to reduce mf migration to the Malpighian tubules [38,48,50].

The minimum extrinsic incubation period herein observed (8 dpi) is consistent with the previous finding in Ae. koreicus [21]. The timing of L3 recovery from the head of Ae. koreicus by Feng [21] (i.e. between 10 and 15 dpi) nicely overlaps with our molecular identification, as well as the time of our first observations of L3 by microscopy (i.e., 16 dpi) is similar to that of D. immitis in Ae. albopictus [46,47].

The likely role of Ae. koreicus as a vector of D. immitis is also corroborated by our IR and VEI values (68.2% and 25.2%, respectively). Indeed, a mosquito species is suggested to be “susceptible” to infection when IR and VEI values are above 10% and 8-9%, respectively [38]. By those criteria Ae. aegypti fed with blood containing 3,000 mf/ml and showing IR = 55.3% and VEI = 6.3% was considered as “refractory” [43] whereas Ae. albopictus fed with blood containing 3,490 mf/ml and showing IR = 28% and VEI = 45.8% was considered susceptible [31].

The risk of canine and human infection by D. immitis in a given area is primarily dependent on the presence of competent mosquito vectors and microfilaremic dogs, although other factors are involved, such as the density of vectors, their host-seeking activity and feeding preference [19,51]. Early studies carried out in north-eastern Italy [13] have shown that Ae. koreicus is well- adapted to urban settlements. The species is found in sympatry with Ae. albopictus, but also in other empty niches. Indeed, the highest density of Ae. koreicus is found in hilly and mountainous habitats, poorly or not yet colonized by Ae. albopictus [13]. Laboratory and field studies suggest a preference of Ae. koreicus for humans, however, the species was able to complete its life cycle when fed with canine blood. Dog blood has also been found in a specimen captured from the field [52]. All these factors, coupled with the likely vector competence of Ae. koreicus for D. immitis, may increase the risk of exposure to D. immitis for dogs and humans in areas where dirofilariosis is present by extending it to areas previously considered at negligible risk in Italy and Europe [19,53].

Further studies on the vector competence of Ae. koreicus for pathogens such as dengue and chikungunya viruses, D. repens and other filarioids are warranted in order to better understand the role played by this recently imported mosquito species in the epidemiology of the diseases they may transmit to animals and humans.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Aedes koreicus, a new invasive species for Europe, is most likely a competent vector of D. immitis, being of potential relevance in the natural cycle of the parasite. This poses a new threat for animal and human health in endemic areas for dirofilariosis and enhances the risk of spreading the infection in previously non-endemic areas. It is important that veterinarians and physicians are aware of the presence of a new competent vector of D. immitis in areas where the risk of dirofilariosis for pets and humans was previously considered negligible. These results stress the importance of active surveillance and control strategies to minimize the risk of introduction of invasive alien species.

References

Medlock JM, Hansford KM, Schaffner F, Versteirt V, Hendrickx G, Zeller H, et al. A review of the invasive mosquitoes in Europe: ecology, public health risks, and control options. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012;12(6):435–47.

Lundstrom JO. Mosquito-borne viruses in Western Europe: a review. J Vector Ecol. 1999;24:1–39.

Schaffner F, Medlock JM, Van Bortel W. Public health significance of invasive mosquitoes in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19(8):685–92.

Sabatini A, Raineri V, Trovato G, Coluzzi M. Aedes albopictus in Italy and possible diffusion of the species into the Mediterranean area. Parassitologia. 1990;32(3):301–4.

Angelini R, Finarelli AC, Angelini P, Po C, Petropulacos K, Macini P, et al. An outbreak of chikungunya fever in the province of Ravenna, Italy. Euro Surveill. 2007;12(9):E070906.1.

Hsiao T, Bohart RM. The mosquitoes of Japan and their medical importance: U.S. NAVMED 1095. Washington DC: Bureau of Medicine and Surgery Navy Department; 1946.

La Casse WJ, Yamaguti S. Mosquito fauna of Japan and Korea. Part I and II. Edited by Corps of Engineers, U. S. ARMY; 1950.

Gornostayeva RM. Checklist of mosquitoes (Culicidae) from the Asian part of Russia. Parazitologiia. 2000;34(5):477–85.

Versteirt V, Pecor JE, Fonseca DM, Coosemans M, Van Bortel W. Confirmation of Aedes koreicus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Belgium and description of morphological differences between Korean and Belgian specimens validated by molecular identification. Zootaxa. 2012;3191:21–32.

Capelli G, Drago A, Martini S, Montarsi F, Soppelsa M, Delai N, et al. First report in Italy of the exotic mosquito species Aedes (Finlaya) koreicus, a potential vector of arboviruses and filariae. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:188.

Bezzhonova OV, Patraman IV, Ganushkina LA, Vyshemirskiĭ OI, Sergiev VP. The first finding of invasive species Aedes (Finlaya) koreicus (Edwards, 1917) in European Russia. Med Parazitol (Mosk). 2014;1:16–9.

Versteirt V, De Clercq EM, Fonseca DM, Pecor JE, Schaffner F, Coosemans M, et al. Bionomics of the established exotic mosquito species Aedes koreicus in Belgium, Europe. J Med Entomol. 2012;49(6):1226–32.

Montarsi F, Martini S, Dal Pont M, Delai N, Ferro Milone N, Mazzucato M, et al. Distribution and habitat characterization of the recently introduced invasive mosquito Aedes koreicus [Hulecoeteomyia koreica], a new potential vector and pest in north-eastern Italy. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:292.

Miyagi I. Notes on the Aedes (Finlaya) chrysolineatus subgroup in Japan and Korea (Diptera: Culicidae). Tropical Med. 1971;13(3):141–51.

Genchi C, Rinaldi L, Cascone C, Mortarino M, Cringoli G. Is heartworm disease really spreading in Europe? Vet Parasitol. 2005;133:137–48.

Otranto D, Capelli G, Genchi C. Changing distribution patterns of canine vector borne diseases in Italy: leishmaniosis vs. dirofilariosis. Parasit Vectors. 2009;2 Suppl 1:S2.

Capelli G, Poglayen G, Bertotti F, Giupponi S, Martini M. The host-parasite relationship in canine heartworm infection in a hyperendemic area of Italy. Vet Res Commun. 1996;20(4):320–30.

Latrofa MS, Montarsi F, Ciocchetta S, Annoscia G, Dantas-Torres F, Ravagnan S, et al. Molecular xenomonitoring of Dirofilaria immitis and Dirofilaria repens in mosquitoes from north-eastern Italy by real-time PCR coupled with melting curve analysis. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:76.

Capelli G, Frangipane di Regalbono A, Simonato G, Cassini R, Cazzin S, Cancrini G, et al. Risk of canine and human exposure to Dirofilaria immitis infected mosquitoes in endemic areas of Italy. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:60.

Cancrini G, Frangipane di Regalbono A, Ricci I, Tessarin C, Gabrielli S, Pietrobelli M. Aedes albopictus is a natural vector of Dirofilaria immitis in Italy. Vet Parasitol. 2003;118(3–4):195–202.

Feng LC. Experiments with Dirofilaria immitis and local species of mosquitoes in Peiping, North China. Ann Trop Med Parasit. 1930;24:347–66.

Cameron EC, Wilkerson RC, Mogi M, Miyagi I, Toma T, Kim HC, et al. Molecular phylogenetics of Aedes japonicus, a disease vector that recently invaded Western Europe, North America, and the Hawaiian islands. J Med Entomol. 2010;47(4):527–35.

Atkins CE. Comparison of results of three commercial heartworm antigen test kits in dogs with low heartworm burdens. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2003;222(9):1221–3.

Capelli G, Ravagnan S, Montarsi F, Ciocchetta S, Cazzin S, Porcellato E, et al. Occurrence and identification of risk areas of Ixodes ricinus-borne pathogens: a cost-effectiveness analysis in north-eastern Italy. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:61.

Sharief AH, Gasim Khalil EA, Barker DC, Omer SA, Abdalla HS, Ibrahim ME. Simple and direct characterization of Leishmania donovani isolates based on cytochrome oxidase II gene sequences. Open Trop Med J. 2011;4:1–5.

Marquez FJ, Muniain MA, Soriguer RC, Izquierdo G, Rodriguez-Bano J, Borobio MV. Genotypic identification of an undescribed spotted fever group Rickettsia in Ixodes ricinus from southwestern Spain. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58(5):570–7.

Massung RF, Slater KG. Comparison of PCR assays for detection of the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis, Anaplasma phagocytophilum. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(2):717–22.

Diniz PP, Schulz BS, Hartmann K, Breitschwerdt EB. “Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis” infection in a Dog from Germany. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(5):2059.

Skotarczak B, Wodecka B, Cichocka A. Coexistence DNA of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato and Babesia microti in Ixodes ricinus ticks from north-western Poland. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2002;9(1):25–8.

Centeno-Lima S, do Rosário V, Parreira R, Maia AJ, Freudenthal AM, Nijhof AM, et al. A fatal case of human babesiosis in Portugal: molecular and phylogenetic analysis. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8(8):760–4.

Tiawsirisup S, Kaewthamasorn M. The potential for Aedes albopictus (Skuse) (Diptera: Culicidae) to be a competent vector for canine heartworm, Dirofilaria immitis (Leidy). Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2007;38 Suppl 1:208–14.

Gerberg EJ, Ward RA, Barnard DR. Manual for Mosquito Rearing and Experimental Techniques. Bulletin No. 5 (revised). Lake Charles, Louisiana: American Mosquito Control Association (AMCA), Inc; 1994. p. 1–98.

Cosgrove JB, Wood RJ, Petric D, Evans DT, Abbot RHR. A convenient mosquito membrane feeding system. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1994;10:434–6.

Taylor AER. The development of Dirofilaria immitis in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. J Helminthol. 1960;34:27–39.

Gander E. ZurHistochemie und Histologie des Mitteldarnies von Aedes aegypti und Anopheles stephensi in Znsammenhang mit der Bintverdannng. Acta Trop. 1968;25(2):131–75.

Santos JN, Lanfredi RM, Pimenta PF. The invasion of the midgut of the mosquito Culex (Culex) quinquefasciatus Say, 1823 by the helminth Litomosoides chagasfilhoi Moraes Neto, Lanfredi and De Souza, 1997. J Invertebr Pathol. 2006;93(1):1–10.

Kartman L. Suggestions concerning an index of experimental filaria infection in mosquitoes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1954;3:329–37.

Kartman L. Factors influencing infection of the mosquito with Dirofilaria immitis (Leidy, 1856). Exp Parasitol. 1953;2:27–78.

Russell RC, Geary MJ. The influence of microfilarial density of dog heartworm Dirofilaria immitis on infection rate and survival of Aedes notoscriptus and Culex annulirostris from Australia. Med Vet Entomol. 1996;10:29–34.

Nayar J, Knight J, Bradley T. Further characterization of refractoriness in Aedes aegypti (L.) to infection by Dirofilaria immitis (Leidy). Exp Parasitol. 1988;66:124–31.

Beerntsen BT, James AA, Christensen BM. Genetics of mosquito vector competence. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:115–37.

Christensen BM. Dirofilaria immitis: effect on the longevity of Aedes trivittatus. Exp Parasitol. 1978;44:116–23.

Serrão ML, Labarthe N, Lourenço-de-Oliveira R. Vectorial competence of Aedes aegypti (Linnaeus 1762) Rio de Janeiro strain, to Dirofilaria immitis (Leidy 1856). Memórias Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2001;96:593–8.

Apperson CS, Engber B, Levine JF. Relative suitability of Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti in North Carolina to support development of Dirofilaria immitis. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1989;5:377–82.

Rossi L, Pollono F, Meneguz PG, Cancrini G. Four species of mosquito as possible vectors for Dirofilaria immitis piedmont rice-fields. Parassitologia. 1999;41:537–42.

Nayar J, Knight J. Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae): an experimental and natural host of Dirofilaria immitis (Filarioidea: Onchocercidae) in Florida, USA. J Med Entomol. 1999;36:441–8.

Konishi E. Susceptibility of Aedes albopictus and Culex tritaeniorhynchus (Diptera: Culicidae) collected in Miki City, Japan, to Dirofilaria immitis (Spirurida: Filariidae). J Med Entomol. 1989;26:420–4.

Buxton BA, Mullen GR. Comparative susceptibility of four strains of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) to infection with Dirofilaria immitis. J Med Entomol. 1981;18:434–40.

Nayar JK, Sauerman DM. Physiological basis of host susceptibility of Florida mosquitoes to Dirofilaria immitis. J Insect Physiol. 1975;21:1965–75.

Sauerman DM, Nayar JK. Characterization of refractoriness in Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) to infection by Dirofilaria immitis. J Med Entomol. 1985;22:94–101.

Ledesma N, Harrington L. Mosquito vectors of dog heartworm in the United States: vector status and factors influencing transmission efficiency. Top Companion Anim Med. 2011;26(4):178–85.

Cazzin S, Ciocchetta S, Ravagnan S, Drago A, Carlin S, Capelli G, Montarsi F. Host preference of the invasive mosquito Aedes koreicus [Hulecoeteomyia koreica]. In Proceedings of XXVIII National Congress SOIPA, 2014: 156, available online at: http://www.soipa.it/images/documenti/attisoipa2014.pdf

Genchi C, Kramer LH, Rivasi F. Dirofilarial infections in Europe. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11:1307–17.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Italian Ministry of Health (project code IZSVE 03/10 RC) and by the Veneto region (project approved by DGRV 1519, 31/07/2012, BUR n.71 28/08/2010). The Authors would like to thank Fabiano D’Este for the adaptation of the movies. Publication of the CVBD10 thematic series has been sponsored by Bayer HealthCare - Animal Health division.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

FM and GC conceived the study and wrote the paper; AFR provided the samples of canine blood and with DO contributed with comments and suggestions to the experimental study; FM and SC performed the study; SC took the pictures and the movies; SR performed the molecular analysis; FMu performed histology; GC performed the Statistical analysis; DO and GD deeply revised the paper. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Dirofilaria immitis larvae L1 in the Aedes koreicus abdomen.

Additional file 2:

Dirofilaria immitis larvae L2 in the Aedes koreicus abdomen.

Additional file 3:

Dirofilaria immitis larvae L3 in the Aedes koreicus abdomen.

Additional file 4:

Dirofilaria immitis larvae L3 in the Aedes koreicus Malpighian tubules.

Additional file 5:

Dirofilaria immitis larvae L3 emerging from the Aedes koreicus proboscis.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Montarsi, F., Ciocchetta, S., Devine, G. et al. Development of Dirofilaria immitis within the mosquito Aedes (Finlaya) koreicus, a new invasive species for Europe. Parasites Vectors 8, 177 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-015-0800-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-015-0800-y