Abstract

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), one of the main types of Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), is a systemic inflammatory disease characterized by dysfunctional pancreatic β-cells and/or peripheral insulin resistance, resulting in impaired glucose and lipid metabolism. Genetic, metabolic, multiple lifestyle, and sociodemographic factors are known as related to high T2DM risk. Dietary lipids and lipid metabolism are significant metabolic modulators in T2DM and T2DM-related complications. Besides, accumulated evidence suggests that altered gut microbiota which plays an important role in the metabolic health of the host contributes significantly to T2DM involving impaired or improved glucose and lipid metabolism. At this point, dietary lipids may affect host physiology and health via interaction with the gut microbiota. Besides, increasing evidence in the literature suggests that lipidomics as novel parameters detected with holistic analytical techniques have important roles in the pathogenesis and progression of T2DM, through various mechanisms of action including gut-brain axis modulation. A better understanding of the roles of some nutrients and lipidomics in T2DM through gut microbiota interactions will help develop new strategies for the prevention and treatment of T2DM. However, this issue has not yet been entirely discussed in the literature. The present review provides up-to-date knowledge on the roles of dietary lipids and lipidomics in gut-brain axis in T2DM and some nutritional strategies in T2DM considering lipids- lipidomics and gut microbiota interactions are given.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is an endocrine metabolic disorder characterized by dysfunctional pancreatic β-cells and peripheral insulin resistance, resulting in abnormalities of glucose metabolism, dyslipidemia, and chronic inflammation [1]. T2DM is commonly associated with poor blood glucose control, dyslipidemia, and obesity, and has become a global public health concern due to the rising prevalence and implications of the disease [2, 3]. In 2021, about 537 million people will be diagnosed with diabetes (DM), and this number is estimated to increase to 643 million by 2030; 90–95 percent of DM diagnoses are T2DM [4, 5].

Genetic, metabolic, lifestyle, and dietary patterns are among the most influential determinants of T2DM [6]. Although ethnicity and family history/genetic predisposition have a substantial genetic basis for developing T2DM, epidemiological studies indicate that T2DM can be prevented by improving modifiable risk factors (obesity, low physical activity, and unhealthy diet) [7, 8]. In genome-wide association studies, the variants in zinc finger gene 1 (JAZF1), insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 2 (IGF2BP2), transcription factor 7 like 2 (TCF7L2), melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R), cell division cycle 123 (CDC123), potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily Q member 1 (KCNQ1), insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA binding protein 2 (IGF2BP2), solute carrier family 16 member 11 (SLC16A11), and PHD finger protein 2 (PHF2) have all been previously were involved in lipid metabolism and were associated with T2DM in adults [9, 10].

Dyslipidemia, caused by elevated plasma triglyceride (TG), increased low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), and reduced high dense lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), is typically observed in T2DM [11]. Mitochondrial dysfunction, ER stress, inflammation, abnormal fatty acid regulation, and β-oxidation may all be involved in dyslipidemia [12, 13]. Excessive dietary intake of free fatty acids (FFA) in patients with T2DM induces the synthesis of phospholipids, glycerolipids, and sphingolipids, hence exacerbating insulin resistance and resulting in lipotoxicity [14, 15]. Currently, lipidomics will help in the understanding of changes in lipid metabolism and elucidate the metabolic pathways underlying the relationship between diet, dyslipidemia, and T2DM.

Lipidomics is a branch of metabolomics that identifies and quantifies the lipids produced by cells in response to pathogenic stimuli [16]. The purpose of lipidomics research is to identify and quantitatively determine the spectrum of intact lipid molecules found in cells and biological fluids, as well as to relate their composition to genetics, proteomics, nutrition, and disease [16, 17]. Recently, increased lipidomic research has been conducted to identify biomarkers for and explain the cellular pathogenic processes of lipid metabolism abnormalities, which play a role in the pathogenesis of several diseases including T2DM, cancer, Alzheimer's disease, cardiovascular disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and obesity [18,19,20,21,22]. Since the 2000s, lipidomics has been used to identify potential predictive and diagnostic parameters of T2DM [23, 24].

Population-based studies have indicated that phospholipids containing glycine, lysophosphatidylcholine acyl, acetylcarnitine, α-hydroxybutyrate, and choline are precursors of glucose tolerance abnormalities. Due to the lack of information on plasma lipidome changes during the shift from prediabetes to T2DM, the plasma lipid that may be used to diagnose T2DM has not been precisely determined. These molecules can influence the interaction along the gut-brain axis, hence contributing to the pathogenesis of T2DM. Furthermore, it has been shown that some lipids such as triglycerides and sphingolipids modulate insulin resistance and T2DM. [25,26,27,28]. The current review summarizes the effect of dietary fats and lipidomics on the gut-brain axis, the role of lipidomics, and possible mechanisms of action in T2DM.

Dietary lipids

Dietary fats are divided into three subgroups: unsaturated FA, saturated fatty acids (SFA), and trans fatty acids (TFA). Unsaturated FA consists of monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) [29]. Although the fatty acid composition of the diet plays a significant role in enhancing insulin sensitivity and reducing T2DM and T2DM-related complications, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. In terms of dietary fat, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concluded in 2010 that a high dietary intake of SFA is a "possible" risk factor for T2DM, while a high intake of TFA is also a "possible" risk factor for T2DM. It has been claimed that PUFA intake was a "possible" positive effect on T2DM, whereas the available evidence for MUFA was insufficient [30]. The widespread view is that the fatty acid composition of the diet might alter cell membrane function [31]. The fatty acid content of the cell membrane regulates several physiological systems, including membrane fluidity, cellular activities, ion permeability, insulin receptor affinity, translocation of glucose transporters interacting with second messengers, and membrane fluidity. All of these alterations can alter the tissue and organ insulin sensitivity [32].

The literature has shown the processes through which FAs exert a direct regulatory influence on gene expression and enzyme function [33]. In vitro, while PUFA (arachidonic acid (AA) > eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) > docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) > linoleic acid (LA)) activates nuclear receptors, including peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR), SFA and MUFA have only a minimal influence on lipogenic gene expression [34, 35]. Furthermore, SFA alters glucose metabolism by regulating inflammatory gene expression, transcription factor activity, and enzyme activity [36]. LA prevents DM through its anti-inflammatory properties. Omega 3 and omega 6 FAs rich in diet can increase insulin sensitivity by suppressing hepatic lipogenesis and promoting FAs oxidation [37].

Many foods contain SFA, but only in low amounts; those of animal origin, including milk, butter, cheese, and meat, are the main sources of SFA in the typical diet. Exceptions include fats derived from tropical plants, which are usually low in SFA but high in the palm and coconut oil. Lauric acid (C12:0), myristic acid (C14:0), palmitic acid, and stearic acid (C18:0) are the majority of dietary SFAs [38]. Palmitic acid and foods derived from animals induce inflammation, oxidative stress, and inflict irreversible harm to cardiometabolic health by interfering with nitric oxide and insulin signaling [39, 40].

A high dietary intake of SFA adversely impacts glucose and lipid metabolism by increasing hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and insulin resistance in metabolic organs such as the liver, pancreas, adipose tissue, and kidney. A diet rich in SFAs decreases the number of large islets in the pancreas, resulting in a more intense insulin response to a glucose load. The structure and function of the islets are altered, resulting in glucose sensitivity and T2DM [41, 42]. It impacts lipid homeostasis, differentiation of adipocytes, fat cell volume and number, and promotes weight gain by increasing the white adipose tissue (WAT) in adipose tissue. All of these alterations accelerate the development of inflammation and leukocyte infiltration in adipose tissue. The accumulation of hepatic triacylglycerol, glucose intolerance, elevated blood sugar, and elevated insulin levels are all consequences of this condition. Increased blood lipid concentrations result in insulin resistance in peripheral tissues, impaired glucose absorption and usage and lipid metabolism, blood circulation and lipid aggregation in various tissues, and metabolic signaling pathways that regulate insulin secretion in pancreatic β-cells. Maintaining the homeostasis of the organism requires tight regulation of glucose and lipid catabolism [43,44,45].

Epidemiological, case–control, and prospective cohort studies have demonstrated that an increase in dietary SFA consumption is associated with the development of T2DM [46,47,48]. Short-term intervention studies indicate that a high SFA diet raises insulin, fasting blood glucose, and Hba1c levels relative to a high MUFA or PUFA diet [49, 50]. However, there are other research suggests that there is no relationship between SFA intake and the onset of T2DM [51,52,53]. It is considered that dietary SFAs influence glucose metabolism and T2DM by inducing insulin resistance.

Trans fatty acids (TFA) are found in ruminant milk and meats, as well as in partially hydrogenated vegetable oils [54]. Some of the metabolic impacts of TFA include an increase in obesity, and insulin resistance, inflammation, and a reduction in endothelial function. TG and lipoprotein (a) levels are increased, whereas total cholesterol (TC):HDL ratio, apoB: apoA ratio, and TC: HDL ratio are all decreased by TFAs [55, 56]. TFA inhibits the antilipolytic impact of insulin in adipose tissue and insulin-mediated glucose transport in animal models. Resistin reduces insulin sensitivity by increasing messenger RNA (mRNA) expression and decreasing PPAR and lipoprotein lipase expression [57, 58].

Olive oil, canola oil, and some plant oils are among the richest sources of MUFA in the diet, whereas red meat, milk, and dairy products also contain MUFA. Olive oil, which is rich in oleic acid (C18:1n-9), and erucic acid (C22:1n-9) are the two most prevalent dietary sources of MUFA in regions where rapeseed oil consumption is prominent [38]. Oleic acid enhances FA oxidation by protein kinase A (PKA)-mediated deacetylation of the Sirtuin1 (SIRT1)-peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor co-activator-1α (PGC1α) complex. Oleic acid exerts an anti-inflammatory effect by participating in several metabolic pathways. Upregulation of M2 expression, the elevation of adiponectin level, the diminution of phosphate and tensin homolog, downregulation of protein phosphatase 2A, and induction of macrophage polarization are all effects of E-selectin, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), interleukin (IL)-6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). Additionally, oleic acid regulates insulin resistance and T2DM by lowering glucolipotoxicity, oxidative stress, and enhancing β-cell function and endothelial and hypothalamus function [45, 59, 60]. A diet that is rich in MUFA increases insulin sensitivity by lowering the glycemic load and insulin requirement. Through an increase in the number of hepatic LDL receptors, it accelerates the turnover of LDL cholesterol. Many beneficial compounds, including phenolic compounds, phytochemicals, and fat-soluble vitamins, are concentrated in foods high in MUFA [61,62,63].

LA and alpha-linoleic acid (ALA) are the only types of necessary FAs that may be obtained from food due to the absence of desaturase enzymes in the human body [64]. Both LA, which is the precursor of omega 6 FAs, and ALA, which is the precursor of omega 3 FAs, are converted to other PUFAs through the addition of double bonds and acyl chains by the enzymes desaturase and elongases, respectively [65, 66]. Omega 3 and omega 6 are both types of FAs that are found in PUFA. Omega 3 FAs consist of long-chain EPA and DHA, both of which are often found in fish, and ALA, which is present in some plant oils such as flaxseed, rapeseed, and canola oil. Canola oil, soybean oil, corn oil, and sunflower oil are just a few of the various plant oils rich in omega 6, particularly LA and dihomo γ LA [67].

Gene expression, the metabolism of prostaglandin and leukotriene, and the synthesis of interleukin (IL)-1 are all significantly impacted by the ratio of omega 6 to omega 3 FAs that exist in the organism under physiological conditions. Omega 3 and omega 6 FAs are in constant competition for desaturation enzymes. In enzymatic processes, fatty acid desaturases 1 (FADS1) and 2 (FADS2) prefer ALA to LA.

A disruption in the ratio of omega 6 and omega 3 initiates a prothrombotic and proinflammatory process that favors omega 6 in the organism and leads to the development of atherosclerosis, obesity, and DM [68, 69]. Long-chain PUFAs improve adipocyte membrane fluidity, GLUT4 RNA and protein levels, hence increasing the number of insulin receptors. Insulin stimulates the activities of desaturases 5 and 6. This increases the amount of insulin receptors on the cell membrane and the affinity of insulin for its receptor, so enhancing the effects of insulin on the organism. However, in the presence of an excess of omega 6 and a deficiency of omega 3, external stimuli release AA from the cell membrane and the formation of proinflammatory mediators [70]. It has been reported that the ratio of omega 6 to omega 3 in the diet should be 1:1 or 2:1 for optimal health [71].

Omega 3 FAs improve insulin sensitivity by reducing ER stress in mitochondria and enhancing the β-oxidation of FAs, thus decreasing the accumulation of lipids and reactive oxygen species (ROS) [59]. Additionally, omega-3 FAs have a beneficial impact on mitofusin 2, a protein implicated in mitochondrial dynamics, homeostasis, and the preservation of the membrane integrity of mitochondria [72]. EPA and DHA modulate insulin sensitivity via Akt phosphorylation, AMP-activated protein kinase, and activating PPARγ [73]. Also, omega-3 FAs regulate pancreatic β-cell insulin secretion by acting on the function and structure of lipid rafts and indirectly reducing the development of proinflammatory mediators in adipose tissue and increasing adipokine synthesis. Omega 3 FAs inhibit inflammatory cytokines, induce adipose tissue to produce adipokines, and increase insulin secretion by directly influencing β-cell activity by binding to PPARs, G protein-coupled receptor 40 (GPR40), and GPR120. PUFA binds to GPR120 in adipose tissue, resulting in increased GLUT4 translocation and glucose uptake in adipose tissue [74, 75].

In randomized controlled trials examining the impact of omega 3 FAs on glycemic control [EPA (2 g/day, 95% pure EPA), fish oil per day (2 g/day EPA + DHA), omega 3 FAs (1.6 g/day EPA and 0.8 g/day DHA)], fasting plasma glucose, HbA1c, and HOMA-IR were reported to be reduced [76,77,78]. Prospective cohort studies have shown that consuming lean fish reduces the incidence of T2DM. It has been observed that consuming lean seafood and fish improves insulin sensitivity and lowers insulin resistance in individuals with insulin resistance [79,80,81,82]. Studies have revealed that EPA and DHA play a significant part in lowering the risk of lipotoxicity and preserving insulin sensitivity [83,84,85]. In several investigations, there was no significant correlation between omega 3 FAs and glycemic indicators such as fasting plasma glucose, insulin, and HbA1c [86,87,88].

There was not enough evidence on the relationship between dietary omega 6 intake, desaturase enzymes, and the incidence of T2DM [67]. In dietary intervention and prospective cohort studies using omega 6 biomarkers/food consumption frequency forms, however, an inverse association was observed between LA and T2DM prevalence [40, 89]. It has been determined that whereas high levels of γ-LA and Di-homo-γ-LA increase the risk of T2DM, high levels of LA diminish this risk. According to research findings, omega 6 may be an indicator of hyperinsulinemia rather than a risk or protective factor for T2DM [90, 91]. In intervention studies that replaced dietary SFA with MUFA, one research revealed that insulin sensitivity was enhanced [92], Other studies have shown that fasting insulin and insulin sensitivity are unchanged [93, 94]. Table 1 shows the classification and nutritional importance of dietary lipids in T2DM. To sum up, it was shown that hepatic fat deposition was reduced and insulin sensitivity increased in interventions involving the consumption of omega 6 instead of dietary SFA [95, 96].

Molecular regulations, and homeostasis of dietary lipids in T2DM

T2DM as a systemic disease as is characterized by hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance, and relative insulin deficiency [6]. The pathogenesis of diabetic complications involves genetic and epigenetic changes, dietary factors, and a sedentary lifestyle [97, 98].

The metabolism of proteins, lipids, and glucose are all significantly regulated by insulin. It participates in the regulation of glucose uptake in muscle, adipose tissue lipolysis, and muscle proteolysis, as well as the metabolism of hepatic glucose and triglycerides [99]. The regulation of lipid metabolism is impacted by increased oxidative and ER stress, hyperglycemia, lipidemia, insulin resistance, and impaired pancreatic beta-cell function in T2DM [100]. Lipid metabolism includes both the biosynthesis and breakdown of lipids like cholesterol, triglycerides, and FAs. Specialized lipoproteins carry lipids from the intestine to the liver (where most lipid conversion occurs) and from the liver to peripheral tissues [101]. Dyslipidemia, T2DM, and obesity are all linked to abnormalities in lipid metabolism, which frequently result in metabolic complications like insulin resistance, DM, ectopic lipid accumulation, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and atherosclerosis [102]. The regulation of lipid metabolism is greatly influenced by nutrients, particularly sugars and FAs [103]. Triglycerides account for 90.0% of all dietary lipids (TG). Phospholipids are also present in cholesterol and cholesterol esters in the diet, in addition to triglycerides [104]. The lingual lipase enzyme and gastric lipase enzymes in the mouth and stomach emulsify the digestion of dietary lipids in adults, but digestion hardly ever occurs. Chyme, a form of lipid, enters the small intestine [105, 106]. The mixture, known as Chyme, causes intestinal cells to secrete the hormone secretin. Secretin facilitates the breakdown of lipids by encouraging the pancreas to secrete bicarbonate, pancreatic lipase, cholesterol esterase, and phospholipase A2. Additionally, cholecystokinin increases bile secretion by promoting gallbladder contraction. Lipids are emulsified in the duodenum with bile salts released from the gallbladder, increasing the surface area of the lipid droplet and improving the efficiency of digestive enzymes [107]. Non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA), CD36, and Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 protein (NPC1L1) for cholesterol are three specific transporters that enable enterocytes to absorb dietary lipids. Triacylglycerols (triglycerides), cholesteryl esters, and other lipids (phospholipids and trace amounts of unesterified cholesterol) come together in enterocytes to form chylomicrons, which are then combined with apolipoprotein (Apo)B-48 (also ApoA-IV and ApoA-I) [108]. Liquid triglycerides make up 90% of the chylomicron mass. These chylomicrons travel from the intestinal mucosa to the lymphatic system via exocytosis, and the large chylomicrons travel from the blood to the liver and adipose tissue [109]. In particular, lipoprotein lipase (LPL) mediates intravascular lipolysis of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TGs in chylomicrons are broken down into FFA and glycerol) and forms chylomicron remnants, which are important for lipid homeostasis and chylomicron clearance [110]. Insulin increases the amount of LPL mRNA, which stimulates LPL. As a result, they control apoC-II and LPL activities in concert through both transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms [111]. The liver cells' ApoE receptors can detect chylomicron remnants. Chylomicrons are more likely to bind to heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) on hepatocyte surfaces and be taken up into the liver by LDL receptor-associated protein (LRP) or LDL-R when ApoE is present. In the process of removing lipoprotein residues, apoE is stored in heparan sulfate proteoglycans. In apoB-48, the ligand binding site is missing [112]. Insulin increases the uptake and clearance of chylomicron residues by inducing the translocation of lipoprotein receptor-related protein to the plasma membrane [113]. By increasing the expression and activity of LDL-receptors, it also encourages LDL clearance [114]. When the 125I-labeled activated α2M (α2M ∗) pathway is activated by insulin secretion increases LRP and LDL-R's function by 2–3 times. Insulin increased the liver's LRP-specific uptake of chylomicron residues, according to a rat study. Postprandial lipoprotein metabolism may suffer if insulin-mediated signaling pathways are disrupted [115]. In HepG2 cells, insulin forms heterodimers with ER small subunit protein disulfide Isomerase to catalyze the transfer of lipid to nascent apoB, a rate-limiting step in the production of hepatic very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL). Additionally, insulin controls the hepatic microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP) metabolism by separating the complex formed by the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, Foxa2, which is phosphorylated in response to insulin action, and PGC-1β [116]. In this study, it was determined that subjects who were insulin resistant had excessive VLDL production and unrestricted MTP expression [117].

The free cholesterol that HDL absorbs from tissues is esterified using lecithin cholesterol acyl transferase (LCAT). Free cholesterol is quickly esterified by LCAT after being absorbed by HDL. They serve as an Apo C and Apo E circulating store for HDL, VLDL, and chylomicrons. They use scavenger receptor B1 (SR-B1) receptors to remove and esterify free cholesterol from extra hepatic tissues and transport it to the liver [118]. Small size HDL (commonly known as HDL3) grows via ester transfer (usually called HDL2) [119]. Also, HDL demonstrates anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-thrombotic, and anti-apoptotic properties [120]. Additionally, VLDL and LDL can exchange lipids via the cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) provided by HDL. In this manner, triacylglycerols are reciprocally transferred from VLDL to HDL and cholesterol esters from HDL to VLDL [121]. The physiological control of HDL cholesterol metabolism depends on insulin. It directly affects the liver, encouraging the transition from HDL2 to HDL3 (through its action on hepatic lipase) [122].

Circulating carbohydrates are transformed into FAs through the intricate process known as de novo lipogenesis (DNL), which is then used to create triglycerides or other lipid molecules. The primary carbon source for the synthesis of FAs comes from the glucose metabolites created during glycolysis [123]. After consuming a large of carbohydrates, circulating glucose is absorbed by adipocytes via insulin-stimulated GLUT4, where it is converted to pyruvate by glycolysis in the cytosol and then transported to the mitochondria for further oxidation in the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA). In the cytosol, novo lipogenesis uses citrate, an intermediate of the TCA cycle, as a substrate. Adipocyte lipogenesis is significantly regulated at the transcriptional level by the protein carbohydrate response element-binding protein (ChREBP). In addition to activating ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY), acetyl-CoA carboxylases 1 (ACC1), fatty acid synthase (FASN), and stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 (SCD1), insulin activates Max-like protein X (MLX) and ChREBP-, which in turn promote the expression of target genes that support the synthesis of FAs [123]. Disruptions in lipid and glucose metabolism and a decline in hepatic glycogen synthesis are brought on by problems with insulin secretion and insulin resistance. Ectopic lipid-induced muscle insulin resistance comes first, followed by liver insulin resistance, which directs ingested glucose to the liver, increasing hepatic de novo lipogenesis and hyperlipidemia [124]. The active role of insulin in normoglycemia and normolpidemia is presented in Fig. 1.

The active role of insulin in normoglycemia and normolipidemia. An overview of Interaction between impared glucose and lipids metabolisim inT2DM. (1) increased chylomicron production, (2) reduced catabolism of both chylomicrons and VLDLs (diminished LPL activity), (3)increased VLDL production (mostly VLDL1), (4) reduced LDL turnover (5) increased production of large VLDL (VLDL1) preferentially taken up by macrophages; LDL (qualitative and kinetic abnormalities): (6) low plasma adiponectin favouring the increase in HDL catabolism. (7) increased number of glycated LDLs, small, dense LDLs (TAG-rich) and oxidised LDLs, which are preferentially taken up by macrophages; (8) increased CETP activity (increased transfer of triacylglycerols from TAG-rich lipoproteins to LDLs and HDLs), (9) increased TAG content of HDLs, promoting HL activity and HDL catabolism, (10) İmpaired glucose metabolisim. (11) İmpaired de novo lipid metabolisim (Acetyl CoA and NADPH inhibit pyruvate dehydrogenase as a result of B oxidation. The lactate and alalnin thus formed increase hyperglycemia because of gluconeogenesis (ketone bodies formation increases) in the liver.) CE cholesterol ester, CETP cholesteryl ester transfer protein, HDLn nascent HDL, HL hepatic lipase, HSL hormone-sensitive lipase, LPL lipoprotein lipase, SR-B1 scavenger receptor B1, TAG triacylglycerol, PP protein phosphatase, PK protein kinase, NEFA non-esterified fatty acids DNL: de novo lipogenesis, LCAT Lesitin-kolesterol acil transferaz, G3P gliserol 3-fosfat protein kinase

The metabolism of glucose and lipids are interconnected in numerous ways. Diabetic dyslipidemia, which is characterized by elevated triglycerides, low HDL-C, and a predominance of small-dense LDL particles, is the most significant clinical manifestation of this interaction [125]. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TRLs) tend to accumulate more frequently in diabetic dyslipidemia [126]. The combination of a defect, excessive production of TRL-apoB-100, also known as very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL, primarily VLDL1) from the liver, and removal of TRL-apoB-48, also known as chylomicrons, from the gut results in diabetic dyslipidemia [127]. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate (PIP2) is converted to phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3) when insulin binds to its receptor, which causes tyrosine phosphorylation, activation of PI3K, and other processes (PIP3). Serine/threonine kinase Akt is activated by PI3K activation, which also inhibits the insulin-mediated inhibition of phospholipase D1 and ARF-1, two components involved in the formation of VLDL1, and decreases the synthesis of ApoB [128]. Both TNF-receptor 1 (TNFR1) and TNF-receptor 2 (TNFR2), as well as the Src homology 2 domain containing RS-1, Akt S473, and T308, and the (Shc) adapter, are less phosphorylated and more insulin resistant because of TNFα induction [129]. Impaired insulin metabolism results in dyslipidemia, which is accompanied by increased apoB stability, MTP, and TNFα release [130]. LPL activity is increased by insulin and decreased by insulin resistance. Chylomicron levels are typically higher in T2DMs with insulin resistance because of both chylomicron overproduction and decreased catabolism. Additionally, through the activation of FOXO1, insulin resistance promotes the production of apoC3, an inhibitor of LPL. The decreased VLDL catabolism is impacted by rising apoC3 serum levels and their impact on LPL metabolism [131].

The treatment of disorders of lipid and insulin metabolism depends on maintaining the ideal dietary balance. Oleic acid consumption that is adequate and well-balanced lowers leukotriene B4 levels and boosts insulin sensitivity, improving insulin sensitivity [60]. LDL-R activity declines and LDL turnover deterioration because of disruption of insulin metabolism. A decline in LDL B/E receptors may be the cause of impaired LDL catabolism (LDL receptor capable of binding apoB and apoE) [132]. In a study, insulin plays a significant role in the expression of LDL-R in vivo and that, in patients with T2DM and poor metabolic control compared with non-diabetic patients, LDL-R expression decreases despite oral anti-diabetic therapy and returns to normal after 3 months of insulin therapy [133]. While macrophages are essential for preserving normal tissue homeostasis, they also play a significant role in the emergence of low-grade inflammation. Insulin resistance results from low-grade inflammation, and low-grade inflammation develops and progresses because of both insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia [134, 135]. The activation of macrophages with the IL-4 and interferon-γ (INFγ) signaling pathways is influenced by insulin-activated IRS-MAPK-PI3K and its modulating protein kinase B (PKB)/Akt kinase pathway [136]. IL-1, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-12, IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-10, and lipopolysaccharide are other proinflammatory cytokines that are linked to increased FoxO1 activity brought on by impaired insulin metabolism. It also influences how macrophages are stimulated [137]. There is various oxidation levels in LDL particles in people with T2DM, from minimally oxidized LDL (MM-LDL) to fully oxidized LDL (Ox-LDL). Due to its negative effects on -cells, an elevated Ox-LDL concentration is also linked, and this creates a vicious cycle, to an increased risk of DM. Initial oxidative changes in LDL lipids occur when apoB-100, also referred to as MM-LDL, is not present. LDL lipids undergo oxidation at a later stage, where they turn cytotoxic and proapoptotic [138]. Because of impaired insulin metabolism, induced regulation of glycated and oxidized LDLs (PI3K/PKB/PPARγ) results in the formation of lipid peroxidation products, cytokine release, ROS production, and inflammation [139, 140]. With their hypolipidemic effect, omega 3 FAs in the diet control how VLDLs are formed in the liver and lower lipogenesis by releasing less TAG [141]. EPA and DHA acids, two long chain omega 3 PUFA, are beneficial for controlling lipid metabolism. apo B is degraded and fatty acid β-oxidation is increased, while TRL apoB-48 secretion and diacylglycerol acyltransferase, fatty acid synthase, and de novo lipogenesis are inhibited, increased, and acetyl CoA carboxylase is carboxylated, respectively, by omega 3 PUFAs [142]. A randomized controlled study found that supplementing with -3 PUFAs (4 g/day, 46% EPA and 38% DHA) significantly decreased the release of TRL apoB-48 [143]. Another randomized controlled trial found that in people with impaired glucose regulation, omega 3 FAs or their combination (2-g fish oil (1000-mg EPA + 400 mg DHA)) significantly reduced inflammation, reduced insulin resistance, and improved glucose and lipid metabolism [144]. Through the inhibition of DNL, an increase in fatty acid oxidation, and a reduction in ApoB synthesis, dietary omega 3 PUFAs prevent the secretion of VLDL [[145]. Additionally, omega 3 PUFAs reduces the production of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α, and TNF- β in response to an inflammatory stimulus, indirectly regulating lipid metabolism [146]. Because they bind to PPARs, GPR40, and GPR120, omega 3 PUFAs have a direct impact on -cell function and increase insulin secretion by inhibiting the production of inflammatory cytokines and eicosanoids and adipokines from adipose tissue [74]. According to the study, supplementing omega 3 PUFAs improves insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis regulation, thereby reducing the risk of developing T2DM [147]. White adipose tissue (WAT) inflammation is increased by high-fat diet models, which also decreases insulin sensitivity and activates Toll-like receptor 4 signaling [148]. A systematic review of the evidence from HFD interventions found that administering HDF for 2 days to 6 weeks to both lean individuals and those with a fat intake of 45–83% as well as overweight or obese individuals increased fatty acid oxidation and maintained impaired insulin sensitivity [149]. In a rat experiment, giving non-glandular Goto-Kakizaki rats HFD increased beta cell dysfunction [150].

Adipocytokines are signaling proteins that play key roles in the regulation of lipid and glucose metabolism, the neuroendocrine system, and the immune system, as well as energy homeostasis [151]. Adiponectin is also an anti-inflammatory adipokine that regulates the synthesis of FAs, glucose uptake, and fatty acid β-oxidation [152]. The expression of adiponectin, its induction by insulin, and its modulation of β-cell function form the basis of the association between adiponectin and insulin resistance/hyperinsulinemia [153]. According to studies, high TNF-α levels and hypoadiponectinemia both contribute to insulin resistance [154]. The study found that people with T2DM have significantly lower serum adiponectin concentrations, which can be a therapeutic parameter for treating people with T2DM [155]. Serum HDL concentrations and circulating adiponectin levels exhibit a strong positive correlation [156]. The major HDL ApoA-I and the ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1), which has the nuclear receptors liver X receptor and PPARγ, are produced more often in the liver when adiponectin is present. Additionally, the formation of large HDL particles (HDL2) from small HDL particles, which is adiponectin's mechanism for reducing HL activity, increases HDL-C (HDL3). In particular, triglyceride hydrolysis in VLDL particles may be increased by adiponectin via upregulation of LPL, reducing triglyceride transfer to HDL [157]. Adiponectin release is influenced by impaired insulin metabolism, which in turn affects lipid metabolism. The development of low HDL-C concentrations is influenced by insulin resistance through many mechanisms. First off, as IR's influence on CETP, which controls insulin, declines, HDL-C levels rise, possibly because of decreased apo A-I production and secretion from the liver and intestine and increased HL. The formation of TG-rich lipoprotein-derived HDL particles is reduced, and HL formation is increased, because of decreased LPL activity. This is because less TG is hydrolyzed from chylomicrons and VLDL [158]. The pathogenesis of T2DM in relation to glucose and lidipi metabolism may also be influenced by adipokines like chemerin, leptin, fetuin-A, retinal binding protein 4, vaspin apelin, nesfatin-1, and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 [159]. Impaired insulin metabolism in T2DM increases lipogenesis, which disrupts lipid metabolism by decreasing glycogen synthesis and glucose metabolism via the TCA cycle [160]. The effect of the regulation of impaired insulin on glucose and lipid metabolism is presented in Fig. 2.

Interaction between impared glucose and lipids metabolism in T2DM. An overview of Interaction between impared glucose and lipids metabolisim inT2DM. (1) increased chylomicron production, (2) reduced catabolism of both chylomicrons and VLDLs (diminished LPL activity), (3)increased VLDL production (mostly VLDL1), (4) reduced LDL turnover (5) increased production of large VLDL (VLDL1) preferentially taken up by macrophages; LDL (qualitative and kinetic abnormalities): (6) low plasma adiponectin favouring the increase in HDL catabolism. (7) increased number of glycated LDLs, small, dense LDLs (TAG-rich) and oxidised LDLs, which are preferentially taken up by macrophages; (8) increased CETP activity (increased transfer of triacylglycerols from TAG-rich lipoproteins to LDLs and HDLs), (9) increased TAG content of HDLs, promoting HL activity and HDL catabolism, (10) İmpaired glucose metabolisim. (11) İmpaired de novo lipid metabolisim (Acetyl CoA and NADPH inhibit pyruvate dehydrogenase as a result of B oxidation. The lactate and alalnin thus formed increase hyperglycemia because of gluconeogenesis (ketone bodies formation increases) in the liver.) CE, cholesterol ester, CETP cholesteryl ester transfer protein, HDLn nascent HDL, HL hepatic lipase, HSL hormone-sensitive lipase, LPL lipoprotein lipase, SR-B1 scavenger receptor B1, TAG triacylglycerol, PP protein phosphatase, PK protein kinase, NEFA non-esterified fatty acids, DNL de novo lipogenesis, LCAT Lesitin-kolesterol açil transferaz, G3P gliserol 3-fosfat protein kinase

Lipidomics, or, more generally, metabolomics, is sensitive to various variables, including the host genotype, s gut microbiota, and diet [161]. The immune system and many other processes, including inflammation, incretin secretion, glucose homeostasis, production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), and bile acid metabolism, are regulated by the intestinal microbiota. Intestinal barrier integrity, pancreatic β-cell proliferation, and short-chain fatty acid synthesis, which supports insulin biosynthesis, can all be negatively impacted by the dysbiosis of the gut microbiota, which can disrupt glucose homeostasis and lead to the onset of T2DM [162, 163]. Different microorganisms can produce different products in metabolomics and lipidomics because each has unique properties [164]. The development of insulin resistance and T2DM may be significantly influenced by FAs. FAs' long-term impact on T2DM is not yet been fully understood, though. Although lipidomics is a relatively underutilized tool, it is used more frequently than genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics to advance our understanding of obesity and T2DM. A subfield of metabolomics called lipidomics may help us better understand how FAs and lipids, particularly insulin resistance and T2DM, contribute to the emergence of health-related complications [165]. Research on T2DM-related gut flora disorders will advance with the integration of gut metabolomics and metagenomics [166].

Dietary lipids and lipidomics in T2DM via gut-brain axis

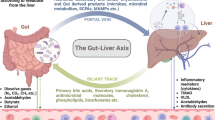

Although dietary lipids and lipidomics play an important role in the development of type T2DM, their effect mechanisms have not yet been fully elucidated. However, the gut-brain axis plays a role in glucose homeostasis [167]. The gut-brain axis is a bidirectional communication pathway. Signals from the brain communicate with the gut via the autonomic nervous system and the hypothalamic-pituitary axis to regulate many physiological processes. Signals from the gut to the brain are mediated by vagal and spinal afferent neurons [168]. The gut-brain axis contains numerous components, containing highly specialized cells responsible for transmitting the information. These are the enteroendocrine cells (EEC), central nervous system (CNS), enteric nervous system (ENS), vagus nerve, and gut microbiota. EECs are specialized trans-epithelial cells found throughout the gut [169]. The ENS, the nervous system of the gastrointestinal tract, consists of various types of neurons, including intrinsic primary afferent and motor neurons [170]. It contains 200 to 400 million neurons and enteric glial cells. It also extends throughout the gastrointestinal tract from the esophagus to the anus [169]. Glucose homeostasis is provided via the CNS and ENS in the gut-brain axis. Ghrelin and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) have emerged as the key factors that can transmit metabolic information to the brain and stimulate endogenous glucose production and usage [171]. The vagus nerve transmits information related to food intake to the brain to regulate energy and glucose homeostasis [169]. Therefore, it is thought that changes in the gut-brain axis may cause T2DM [170].

Gut microbiota is also considered an important part of the gut-brain axis, so the microbiota-gut-brain axis is emerging as a prominent factor nowadays [169]. Gut microbiota is a collection of more than 100 trillion microorganisms (bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and viruses) and their genomes found in the gastrointestinal tract [172]. Intestinal microorganisms colonize the gastrointestinal tract and contribute to homeostatic balance under healthy physiological conditions [173]. While the host provides a nutrient-rich environment for microorganisms, microorganisms also affect host physiology, immunology, and metabolism [174]. Gut microbiota is the main mediator of the gut-brain axis in the regulation of glucose homeostasis. It contributes to glucose homeostasis by regulating the immune system, inflammatory response, modulation of incretin secretion, production of SCFA, and metabolism of bile acids [171]. Gut microbiota produces several metabolites that directly and indirectly affect the gut-brain axis. GLP-1 is an endocrine factor that may be involved in the control of the gut-brain axis by the gut microbiota [170]. Cani et al. (2006) demonstrated that the modulation of gut microbiota improves glucose metabolism via a GLP-1-dependent mechanism [175]. Gut microbiota can affect serotonin (5-HT) production by EECs, altering ENS vagal afferent activation. Bile acids can also alter the expression of Takeda-G-protein-receptor-5 (TGR5) and affect intestinal peptide release from EECs. SCFAs can alter nutrient receptor expression and intestinal peptide production by EECs or can directly activate vagal afferents. Lipopolysaccharides (LPS), a products of pathogenic microorganisms, can impair gut-brain signaling by preventing the activation of vagal afferents or the ENS [168].

Microbiota dysbiosis is the disruption of intestinal homeostasis by altering the composition of the gut microbiota [172]. A direct causal relationship between gut dysbiosis and the development of has not been identified. However, immunomodulatory mechanisms mediated by microbiota-derived lipids have been discovered. The most well-known is the release of LPS and decreased SCFA production, which have pro-inflammatory effects. Other suggested mechanisms include altered bile acid metabolism, altered secretion of incretin hormones such as GLP-1, altered circulating branched-chain amino acids, and impaired adipose tissue, liver, or skeletal muscle functions [163, 176]. This results in increased colonic permeability, colon, liver, and adipose tissue inflammation, impaired insulin secretion, the occurrence of insulin resistance, impaired glucose and lipid metabolism, and the development of T2DM [163]. Microbiota dysbiosis in T2DM is characterized with decreased numbers of SCFA-producing gram-positive bacteria and increased numbers of LPS-producing gram-negative opportunistic pathogens [176]. In a recent study, T2DM patients exhibited a higher Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio than healthy individuals. Bacterial diversity in the gut microbiota was reduced in patients with prediabetes or T2DM compared with healthy individuals [163]. In another study, it was observed that T2DM patients had a decreased concentration of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. It has anti-inflammatory properties, promotes the proliferation and growth of epithelial cells and increases the synthesis of tight junction proteins. Ruminococcus bromii, which contributes to the production of SCFAs, was also reduced in T2DM patients [177]. A study showed that the colonization of germ-free (GF) mice with healthy gut microbiota caused the restoration of neuronal GLP-1 and ENS signaling pathways in the gut. However, it was indicated that this effect was eliminated by colonization with the diabetic gut microbiota [178]. Another study showed that transplantation of fecal microbiota from lean donors to individuals with metabolic syndrome caused improved insulin sensitivity in the recipients. This suggests that healthy gut microbiota can improve metabolic outcomes [179]. Furthermore, the improvement in glucose homeostasis is associated with GLP-1R signaling, indicating that prebiotic-induced changes in the microbiota restore the gut-brain axis [175]. Promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria using indigestible carbohydrates can improve glucose tolerance [180]. The gut-brain axis pathways related to T2DM was shown in Fig. 3.

Dietary lipids in T2DM via gut-brain axis

Dietary lipids affect the gut microbiota composition, metabolic-end products, other enzymatic markers, and all microbiota-related diseases [181]. However, the mechanisms of the interplay between dietary lipids and gut microbiota in glucose homeostasis have not been well defined. Many dietary FAs are absorbed in the small intestine; however, some of them directly affect the colonic microbiota composition. It has been shown that gut microbiota can affect glucose and lipid metabolism and may even cause T2DM by disrupting the balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects in the liver. A diet rich in saturated FAs can adversely affect the microbiota composition and reduce insulin sensitivity [182]. A high-fat diet increases the amount of Firmicutes and decreases the amount of Bacteroidetes, which may lead to the development of T2DM [183]. Conversely, a diet high in omega 3 FAs and MUFA may promote a favorable alteration of microbiota composition in T2DM patients [87, 184]. Table 2 summarizes the role of dietary lipids on gut microbiota and T2DM.

High fat

High-fat diets cause decreased gut microbiota diversity, increased number of gram-negative bacteria, increased LPS translocation, increased intestinal permeability, systemic inflammation, and impaired immune system [184].

High-fat diets cause the loss of beneficial microorganisms and disrupt the symbiotic relationship between the gut microbiota and the host [185]. High-fat diets are associated with lower Bifidobacterium species and higher plasma LPS concentration. Likewise, it has been observed that the growth of Desulfovibrio bacteria, which are gram-negative, opportunistic pathogens and produce LPS, during high-fat feeding in mice [148]. LPS, also known as endotoxin, is a structural compound in the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria [103]. LPS initiates low-grade inflammation by activating Toll-Like Receptor 4 (TLR-4), which is expressed in macrophages, hepatocytes, and adipocytes [172]. This mechanism includes several steps. In the first step, LPS binds to lipopolysaccharide-binding proteins (LBP) and interacts with a cluster-of-differentiation 14 (CD14), which is a glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol-anchored protein. In the second step, TLR-4 is activated, triggering a signaling cascade that ends with phosphorylation and activation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) in enterocytes. In the third step, FAK increases intestinal permeability by regulating IL-1R-associated kinase 4 (IRAK4)-related myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88) activation. In the final step, LPS translocates into the systemic circulation and causes the release of interleukins. IL-6 causes a low-grade inflammation that affects insulin signaling and triggers insulin resistance. This step constitutes the onset of pancreatic β-cell dysfunction [177]. Additionally, LPS stimulates the innate immune signaling cascade by enhancing the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), which is an effector of the innate immune system and synthesizes nitric oxide. iNOS disrupts insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) expression. Thus, this can result in hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance, and T2DM [172].

A healthy intestinal epithelium acts as a barrier to preventing the migration of bacterial-derived factors and prevents LPS from entering the systemic circulation [103]. However, high-fat diets disrupt intestinal barrier function, allowing LPS translocation. This condition, called metabolic endotoxemia, can cause decreased pancreatic β-cell function, insulin resistance, and T2DM [184].

Animal studies have revealed that long-term high-fat feeding is associated with increased circulating LPS [186, 187]. Cani et al. (2007, 2008) reported that endotoxins were approximately 1.5 times higher in lean and obese mice fed a high-fat diet (72% of total energy) than in mice fed a normal diet for four weeks [180, 188]. In previous studies, mice fed a high-fat diet developed hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance, which are associated with decreased intestinal mucus thickness and increased intestinal permeability [180, 189, 190]. In an animal study, mice were fed a low-fat (10% of total energy) or high-fat (60% of total energy) diet for eight weeks. High-fat diets increased proinflammatory cytokines, plasma endotoxin levels, and Firmicutes/Bacteriodetes ratio, resulting in intestinal dysbiosis. Additionally, fasting blood glucose and insulin concentrations were higher in high-fat-fed mice than in low-fat-fed mice [191]. Richards et al. (2016) showed that GLP-1 release was reduced in mice fed a high-fat diet (60% of total energy) for two weeks. They also found that the expression of L-cell-specific genes decreased in mice fed a high-fat diet for sixteen weeks. This suggests a disruption in enteroendocrine cell function and gut-brain axis [169].

High-fat diets have been associated with increased LPS levels in humans [192, 193]. Ghanim et al. (2009) showed that a high-fat and high-carbohydrate meal increased the LPS levels and TLR-4 expression [194]. Liang et al. (2013) reported that high LPS levels were negatively associated with skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity in obese individuals with or without T2DM [195]. A study conducted in humans found that endotoxin levels increased in individuals with glucose intolerance and T2DM (respectively, 20% and 125%) [193]. Gomes et al. (2017) reported that LPS levels in patients with diabetes were 66.4% higher than in nondiabetic patients. Additively, it was shown that TLR-4 expression was higher in patients with diabetes compared to nondiabetic patients [196]. It was evidenced that mice lacking CD14, a co-receptor of TLR-4, were more hyperinsulinemia-resistant and insulin resistance induced by a high-fat diet or LPS [188]. Therefore, deletion or mutation of the gene encoding TLR-4 may protect against fatty acid-induced insulin resistance and T2DM [197, 198]. Hulston et al. (2015) reported that a high-fat diet (65% of total energy) impaired insulin sensitivity in healthy and non-obese individuals. Besides, probiotic supplementation (Lactobacillus casei) for four weeks maintained normal insulin sensitivity [199]. Animal and human studies indicate that high-fat diets may cause the development of T2DM by affecting the gut-brain axis and gut microbiota.

Saturated fatty acids

SFAs have been associated with increased non-commensal bacteria (Firmicutes and Proteobacteria), intestinal barrier dysfunction, decreased gut microbiota diversity, thinning of the mucus layer, decreased butyrate-producing bacteria, chronic inflammation, and development of T2DM [181]. addition SFAs cause ER stress. ER stress-associated systemic inflammation also induces disruptions in insulin signaling pathways. Systemic inflammation is considered a precursor to the development and progression of insulin resistance [172].

Animal studies have found that a high-fat diet increased Firmicutes and decreases Bacteroidetes in the gut microbiota. This is associated with insulin resistance resulting from intestinal inflammation [188, 200, 201]. An animal study showed that a saturated fat diet increased insulin resistance, intestinal permeability, and mesenteric fat inflammation [202]. Caesar et al. (2015) compared rats fed a high-fat diet rich in SFAs as lard to an isocaloric high-fat diet rich in omega 3 FAs as fish oil. It was found that Akkermansia muciniphila, Lactobacillus, and Bifidobacterium, which are beneficial bacteria, were less in the microbiota of the mice fed a high-fat lard diet. Moreover, a high-fat lard diet activates TLR-4 signaling, reducing insulin sensitivity and increasing inflammation in white adipose tissue [203]. In an animal study comparing lard-based and palm oil-based diets, lard-based diets were associated with impaired glucose tolerance. Lard-based diets also alter gut microbiota composition and function, acting on lipid metabolism [204]. Although there is a limited number of human intervention studies on SFAs, data from animal studies suggest that SFAs causes intestinal dysbiosis, leading to insulin resistance and T2DM.

Omega 3 fatty acids

Omega 3 FAs can prevent insulin resistance and T2DM development by increasing the diversity of the gut microbiota, reducing LPS and proinflammatory cytokines, and increasing SCFA production. Omega 3 FAs may exert beneficial effects on the gut microbiota by reducing the proliferation of Enterobacteriaceae, increasing the proliferation of Bifidobacterium, and subsequently inhibiting the inflammatory response associated with metabolic endotoxemia [205]. Besides, it was reported that a high intake of omega 3 FAs was associated with an increased translocation of commensal bacteria (Bifidobacterium and Akkermansia) and a decreased Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio [181]. Omega 3 FAs inhibit LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine production in human blood monocytes and attenuate intestinal inflammation [206]. However, omega 3 fatty acid supplementation has not yet been demonstrated to affect insulin metabolism and gut microbiota [87].

Patterson et al. (2014) showed that a flaxseed/fish oil diet for sixteen weeks significantly increased the intestinal population of Bifidobacterium in mice [207]. Administration of omega 3 FAs to Salmonella-infected mice increased the amount of SCFAs, altered the gut microbiota, and supported host resistance to pathogens [208]. In a prospective study, thirty-five patients with T2DM were randomly assigned to a standard T2DM diet group and a standard T2DM diets enriched with 100 g of sardines group. There was no significant difference between the glycemic controls of the patients in either groups. Plasma insulin and insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) decreased from baseline in both groups. Firmicutes decreased in both groups after six months of intervention. Patients fed a standard T2DM diet enriched with sardines had a decreased Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio [87]. The dietary intake of fish oil has increased the diversity of intestinal flora more than sunflower oil [209]. A diet high in omega 3 FAs has been observed to increase the number of several SCFA-producing bacteria in the human gut microbiota, including Blautia, Bacteroides, Roseburia, and Coprococcus [210]. An animal study showed that alpha-linolenic acid-rich flaxseed oil significantly reduced fasting blood glucose, HbA1c, LPS, IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 levels. Additionally, flaxseed oil intervention increased acetate, propionate and butyrate levels. Flaxseed oil eased T2DM by suppressing inflammation and regulating the gut microbiota. Firmicutes and Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratios decreased, while Bacteroidetes increased [211]. All these studies suggest that omega 3 FAs reduces the risk of T2DM development by increasing SCFA production. However, data from both animal models and human interventions are not enough and uncertain.

Omega 6 fatty acids

Animal studies have shown that high-fat diets containing large amounts of omega 6 FAs increase Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria and decrease Bacteroidetes [201, 212]. Thus, omega 6 FAs may cause T2DM, raising intestinal dysbiosis. Miao et al. (2020) showed that both dietary omega 6 FAs and circulating omega 6 FAs (gamma-linolenic acid) could increase the risk of T2DM through a mechanism that alters the diversity and composition of the gut microbiota. Additionally, gamma-linolenic acid was inversely related to butyrate-producing bacteria in this study. Omega 6 FAs can increase the secretion of bile acid, which may act as an important signaling molecule linking omega 6 FAs and the gut microbiota. Bile acids can be metabolized in the gut to deoxycholic acid, which can disrupt hepatic ER stress. Therefore, it can disrupt glucose homeostasis and cause T2DM [213]. Although omega 6 FAs may play a role in the development of T2DM by the microbiota-gut-brain axis, more animal and human studies are needed in this field.

Lipidomics in T2DM via gut-brain axis

Lipidomics plays a major role in glucose homeostasis and the development of T2DM. It has been shown that the gut microbiota composition is altered in individuals with T2DM. However, the relationship between gut microbiota and lipidomics needs to be clarified in T2DM [214]. Animal studies suggest that the gut microbiota may modulate the lipidomics of the host. Homeostasis between lipidomics and gut microbiota is also known to affect the metabolic state of the host [204]. Furthermore, gut microbiota can synthesize lipids and their metabolites that may impact human health. Changes in gut microbiota and host lipidome appear to be associated with the development of T2DM [215]. However, there are few studies on lipidomics and its relationship to the gut-brain axis in T2DM [216].

Sphingolipids

Sphingolipids are bioactive lipids that regulate cellular processes such as cell differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, and inflammation. Sphingolipids can be obtained either by diet or de novo synthesis [215]. However, it has been reported recently that the commensal gut microbiota (Bacteroides, Prevotella, and Porphyromonas) also produces sphingolipids. Ceramide phosphoinositol and deoxy-sphingolipids are synthesized by gut microbiota. These sphingolipids can exacerbate intestinal inflammation and regulate the amount of ceramide in animals. Sphingolipids may be an early marker of impaired glucose metabolism, but there are limited human studies with conflicting results [217].

Ceramides are precursors to sphingolipids [218]. Ceramides may be associated with insulin resistance because they may interfere with insulin signaling. It has been reported that ceramide levels are increased in serum, liver, and skeletal muscle in T2DM patients. Ceramides can trigger adipose tissue inflammation and diabetic pathology, activating pro-inflammatory cytokines [219]. In another study, ceramides were found to be positively associated with HOMA-IR in patients with T2DM [220]. Holland et al. (2011) showed that ceramides mediated saturated FAs-induced insulin resistance by TLR-4 signaling in skeletal muscle [218]. In 435 American-Indian participants in the Strong Heart Family Study, higher levels of ceramides, including stearic acid, arachidic acid, and behenic acid, were associated with T2DM [221]. In another study conducted in China, ceramides (18:1/18:1, 18:1/20:0, 18:1/20:1, 18:1/22:1), saturated sphingomyelins (C34:0, C36:0, C38:0, C40:0), unsaturated sphingomyelins (C34:1, C36:1, C42:3), hydroxyl-sphingomyelins (C34:1, C38:3) and hexosylceramide (d18:1/20: 1) was associated with T2DM. This study demonstrated that high levels of ceramides and sphingomyelins accompany pancreatic β-cell dysfunction [23].

Many lipidomics other than ceramides has been defined in T2DM patients. Thirty-five newly diagnosed T2DM patients had higher levels of sphingomyelins (d18:1/18:0, d18:1/18:1), ceramides (d18:1/18:0, d18:1/16:0, d18:1/20:0, d18:1/24:1), lysophosphatidylcholines (15:0, 16:0, 17:0), phosphatidylcholines (19:0/19:0), lysophosphatidylethanolamines (18:0), and phosphatidylethanolamines (16:0/22:6, 18:0/22:6) than the control group. Conversely, phosphatidylethanolamines (17:0/17:0) and phosphatidylcholines (18:1/18:0) were lower in T2DM patients. Levels of serum sphingomyelins (d18:1/18:0, d18:1/18:1), lysophosphatidylcholine (16:0), and lysophosphatidylethanolamines (18:0) decreased after administration of GLP-1 analog [222]. Floegel et al. (2013) associated diacyl-phosphatidylcholines C32:1, C36:1, C38:3, and C40:5 levels with an increased risk of T2DM. On the contrary, sphingomyelin C16:1, acyl-alkyl-phosphatidylcholines C34:3, C40:6, C42:5, C44:4, C44:5 and lysophosphatidylcholine C18:2 were associated with a reduced risk of T2DM [223]. Lysophosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, and diacylglycerol have been associated with an increased risk of T2DM. Unlike, sphingomyelins have been related to a reduced risk of T2DM [26]. In the Metabolic Syndrome in Men (METSIM) cohort consisting of 10.197 men in total, it was found that levels of triacylglycerol and di-acyl-phospholipids were higher in T2DM patients [224]. Lysophosphatidylcholine was determined to stimulate glucose uptake in 3T3-L1 adipocytes in a dose- and time-dependent manner [225]. Prada et al. (2020) informed a negative correlation between lysophosphatidylcholine and T2DM risk in females. There was a positive correlation between lysophosphatidylcholine and T2DM risk in males. In addition, cholesteryl esters, monoacylglycerols, and diacylglycerols showed an inverse association with T2DM. A positive correlation was found between FFA and T2DM risk [226].

Although sphingolipids seem to be related to glucose metabolism, the effect of the gut-brain axis on this relationship is not yet known. Liu et al. (2019) presented that gestational diabetes was strongly associated with a specific gut microbiota composition and lipidomics. This study showed that Faecalibacterium and Prevotella species were related to lysophosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylglycerol [214]. Further and larger studies are required to investigate the effect of the gut-brain axis on lipidomics and glucose metabolism.

Bile acids and derivatives

Primary bile acids are synthesized from cholesterol in hepatocytes [168]. Primary bile acids are conjugated with glycine or taurine to form bile salts. About 95% of bile acids are reabsorbed in the ileum into the hepatic portal vein and then into the liver sinusoids. About 400–600 mg of bile salts reach the colon. They are converted to secondary bile acids such as deoxycholic acid, lithocholic acid, and ursodeoxycholic acid by the colonic microbiome [176]. However, secondary bile acids are produced or biotransformed by the gut microbiota. Conjugated primary bile acids are deconjugated by Bacteroides, Clostridium, Lactobacillus, and Bifidobacterium species. The gut microbiota plays an important role in bile acid metabolism. In addition, both primary and secondary bile acids affect host metabolism [215]. Bile acids regulate glucose homeostasis, lipid metabolism, and gut microbiota [227].

It has been suggested that secondary bile acids may cause T2DM through the gut microbiota. Taurine-conjugated bile acids have been associated with insulin resistance in nondiabetic individuals. They have been significantly higher in patients with T2DM than those without T2DM [228, 229]. In a study, insulin resistance was associated with increased levels of secondary bile acids [230]. In addition, deoxycholic acid, a secondary bile acid, was positively correlated with Firmicutes levels [231]. In particular, a high-fat diet alters the gut microbiota, increasing intestinal, brain, and blood levels of taurine-conjugated bile acids such as taurochenodeoxycholic acid, a Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) agonist. Increased taurochenodeoxycholic acid may cause insulin resistance by increasing TCDCA-FXR signaling [232]. There is evidence that microbiota dysbiosis can cause T2DM by increasing secondary bile acids; however further animal and human studies are required.

Endocannabinoids

The endocannabinoid system consists of lipid-derived endogenous ligands, enzymes involved in their synthesis and degradation, and cannabinoid receptors [215].

Gut microbiota has close linked to the endocannabinoid system. It has been suggested that the gut microbiota and endocannabinoids may communicate with signaling pathways involving the gut-brain axis for homeostasis of energy, lipid, and glucose metabolism. N-acyl phosphatidylethanolamine-specific phospholipase D regulates lipid absorption and metabolism. Its disruption causes insulin resistance, glucose tolerance, and intestinal dysbiosis [215]. Muccioli et al. (2010) demonstrated a relationship between the gut microbiota and the endocannabinoid system that modulates host adipogenesis [233]. Everard et al. (2013) showed that Akkermansia muciniphila intervention in obese mice increased intestinal levels of 2-oleoylglycerol, 2-arachidonoylglycerol, and 2-palmitoyl-glycerol [189]. More recently, it was reported that the endocannabinoid-like molecule N-acyl-3-hydroxypalmitoyl-glycine was synthesized by Bacteroides species [234]. These studies suggest that the gut microbiota generates lipidomics that influences signaling pathways of host metabolism. The mechanisms related to the gut microbiota that mediate the increase in intestinal permeability have not been fully elucidated. However, overactivation of the endocannabinoid system may play an important role in intestinal permeability [235]. In addition, endocannabinoids can affect the composition of the gut microbiota. Deletion of the endocannabinoid-synthesizing enzyme in adipose tissue may cause obesity, glucose intolerance, altered lipid metabolism, and adipose tissue inflammation [236].

Specialized pro-resolving mediators

Specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs) are synthesized from AA, eicosapentaenoic acid, docosahexaenoic acid, and docosapentaenoic acid during inflammation. These endogenous lipids promote the clearance of pathogenic bacteria and macrophages associated with microbiota dysbiosis. They also enhance tissue regeneration by increasing the secretion of anti-inflammatory mediators and inhibiting proinflammatory cytokines. These lipid mediators play a crucial role in eliminating inflammation, maintaining intestinal integrity, and preventing T2DM [181].

Short chain fatty acids

SCFA, which are organic FAs containing 2–6 carbon atoms, are synthesized in the host's colon by the microbiota following fermentation of indigestible dietary fibers, proteins, and glycoproteins. Acetate, propionate, and butyrate account for 95% of SCFAs present in the colon [170]. SCFA-producing commensal bacteria include Lachnospira, Akkermansia, Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Ruminococcus, Roseburia, Clostridium, Faecalibacterium, and Dorea. SCFAs, which are used as substrates for energy production, lipogenesis, gluconeogenesis, and cholesterol synthesis, affect host metabolism. SCFAs act as signaling molecules by stimulating G protein-coupled receptors GPR43/FFAR2 and GPR41/FFAR3. GPR43 increases GLP-1 expression by affecting L cells. Acetate regulates glucose and lipid metabolism via GPR43 [215]. Acetate and propionate exert anti-inflammatory effects by FFAR2. This receptor signaling results in the inhibition of NF-kB nuclear translocation and decreased expression of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6. Preventing inflammation can also reduce the risk of T2DM [177].

Microbiota dysbiosis can cause T2DM development by decreasing SCFA concentrations [237]. The composition of the gut microbiota and diet affect the type and amount of SCFA. High-fat diets and some FAs can result in decreased SCFA production and increased harmful secondary metabolite production. Increased intestinal permeability can cause low-grade inflammation and metabolic endotoxemia. Metabolic endotoxemia can also cause insulin resistance, β-cell dysfunction, hyperglycemia, and T2DM [238]. High-level endotoxemia has been found to increase TNF-α and IL-6 concentrations and insulin resistance [239]. Recent evidence suggests that dietary lipids and lipidomics can cause T2DM by reducing SCFA production. However, the effect of SCFAs on the pathophysiology of T2DM has generally been observed in animal studies, but these results should be confirmed in larger, long-term studies with clinical endpoints.

Nutritional strategies modulating gut microbiota through lipidomics for T2DM

To promote health, it is now essential to understand how nutrients impact metabolic control [240]. It is well known that a wide range of exogenous and intrinsic factors affect the intestinal microbiota. The human gut microbiota can be shaped and modified by a number of factors, but diet is one of the most potent [241]. Food is the primary source of energy for microorganisms in the gut, and changes in the host's diet can result in rapid changes in the microbiota's composition [241, 242]. Up to 57% of changes in the gut microbiota may be attributed to dietary factors, but host genes are only thought to be responsible for 12% or less of those changes [243]. To combat noncommunicable diseases like T2DM, including understanding how diet and dietary nutrient intake affect the gut microbiome, is crucial [244]. This makes it crucial to identify the dietary components that influence the gut microbiome, where dietary lipids play a significant role [181, 244]. Roles and mechanisms of lipidomics in T2DM were discussed in the sections before this one. It is possible that T2DM can be prevented and treated by modulating lipidomics, according to this. A key role in the modulation of lipidomics is played by nutritional status and dietary nutrients. It is stated that especially dietary lipid intake may have anti-diabetic effects with the changes it has created on the composition of the intestinal microbiota through metabolic end products [211, 245,246,247]. The possible roles that some nutritional strategies may play in T2DM through lipidomics and gut microbiota were shown in Fig. 4.

Fatty acids

Omega 3 fatty acids

High consumption of fish and seafood is associated with a significantly lower risk of T2DM [248, 249]. It is reported that high omega 3 FAs content may be effective in this situation through different mechanisms such as anti-inflammatory and antioxidant [249,250,251]. Another potential mechanism is that it lowers the risk of developing T2DM by influencing the intestinal microbiota through lipidomics, which is a substance produced in the intestine as a result of the metabolism of omega 3 FAs [248, 252].

It is known that the intestinal microbiota can be modulated through SCFAs, and in this way, the microbial diversity of the intestine can be changed [253]. SCFAs increase insulin signaling and insulin sensitivity with their curative effects on systemic inflammation and endotoxemia by decreasing intestinal permeability [248]. Additionally, SCFA enhances glucose uptake in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue by boosting GLUT4 expression via AMP Kinase (AMPK) activity [254]. Bacteria that produce butyric acid contribute significantly to maintaining health by converting unfermented dietary fibers into SCFAs such as butyrate [248]. It has been reported that supplementation of omega 3 FAs helps modulate the intestinal microbiota by increasing the level of SCFAs in the intestine [252]. In addition, a diet rich in omega 3 FAs is noted to significantly increase butyrate-producing bacteria, including Blautia, Bacteroides, Roseburia, and Coprococcus [248, 252].

Another of the main mechanisms of the protective function of omega 3 FAs is their influence on the lipidome, including eicosanoids and membrane lipids [255]. Yan et al. (2020) found that omega 3 fatty acid supplementation in healthy individuals added glycerophospholipidome levels [255]. In a study carried out with non-obese T2DM rats and Wistar rats, it was detected that dysbiosis occurred and higher glycerophospholipids were present in non-obese T2DM rats when compared with Wistar rats. Another outcome of the study was that omega 3 supplementation significantly affected plasma glycerophospholipids [256]. Considering their effects on the lipidome, these data suggest that omega 3 FAs may influence the intestinal microbiota and subsequently T2DM. In research, the effects of supplements containing varying doses of EPA + DHA and dietary sources of omega 3 such as fish and flaxseed oil on intestinal microbiota were investigated. The research outcomes are influenced by sample size, methodological variations, the study group, and the dose and amount of the supplement or nutritional source utilized.

Omega 6 fatty acids

Vegetable oils, nuts, and seeds are the main dietary sources of omega 6 PUFAs. The essential omega 6 FAs in the diet are LA and AA. LA makes up the majority (about 90%) of dietary PUFAs, while AA has a lower intake [257]. In the body, the majority of LA is transformed into AA [258]. For several enzymes, AA serves as a substrate [181]. Different biosynthetic pathways (i.e., cyclooxygenases (COX), lipoxygenases (LOX), or cytochrome P450) of these enzymes are used to produce various eicosanoids, including various prostaglandins, thromboxanes, and leukotrienes [259]. According to recent research, the majority of immune cells and intestinal epithelial cells synthesize eicosanoids [181, 260]. Additionally, it is claimed that by metabolizing AA, intestinal bacteria can produce eicosanoid metabolites [181]. Particularly, it has been reported that proteobacterial lipoxygenases can generate a variety of prostaglandins in the intestine by fermenting other bacterial byproducts, primarily SCFAs [181, 261].

Cyclooxygenase pathway metabolites of AA, especially prostaglandins, increase the risk of T2DM by causing pancreatic β-cell destruction and β-cell dysfunction [262]. In line with such data, dietary omega 6 FAs may be considered to role in the development of T2DM through enzyme systems and eicosanoid metabolites produced as a result of their metabolism by intestinal bacteria.

Dietary sterols

Sterols are lipophilic substances that can be divided into synthetic sterols, phytosterols (derived from plants), zoosterols (derived from animals), and mycosterols (derived from fungi) [263]. About 30–60% of dietary cholesterol is absorbed, while the rate of absorption for plant sterols is much lower (2–3%) [264]. This means that unabsorbed sterols can reach the colon and be further processed by the gut microbiota [181, 264]. Among the common phytosterols, β-sitosterol, stigmasterol, campesterol, and brassicasterol can be found in both plant cells and cytoplasmic membranes of many fruits, vegetables, nuts, cereals, and vegetable oils [263]. Western nations consume about 250 mg of phytosterols per day on average [265].

Metabolites produced as a result of transformation by the gut microbiota of unabsorbed sterols, including cholesterol and plant sterols, have significant effects on the host's health, including in T2DM, through modulation of the gut microbiota [264]. Coprostanol, coprostanone and cholestanol are cholesterol metabolites formed in the gut by the gut microbiota [264, 266]. Coprostanol is the most abundant animal sterol in feces, followed by coprostanone and cholesterol, which can be converted to lesser cholestanol [264].

Plant sterol supplementation was found to increase the production of SCFAs and decrease the production of coprostanol and ethylcoprostanol in a study where the researchers evaluated the effects of plant sterols on the intestinal microbiota (acetate and butyrate). Additionally, it was reported that this supplement could improve the gut microbial profile by raising the percentage of some genera from the phylum Firmicutes [267]. In another study, in which half of 40 postmenopausal women were given a 2 g/day plant sterol-enriched beverage and the remaining half a placebo for six weeks, it was found that the coprostanol levels were lower in the feces of the plant sterol group, and it was concluded that plant sterols could be used to modulate the gut microbiota [268]. In addition, Weststrate et al. discovered that plant sterol-enriched margarine (8.6 g/day) decreased the amount of cholesterol that was converted to coprostanol during metabolism [269]. In line with the data obtained from these studies, it can be concluded that while plant sterols decrease the production of some lipidomics such as coprostanol, they increase the production of SCFAs. As mentioned in earlier sections, SCFAs lower the risk of developing T2DM via a variety of mechanisms, including modulation of the gut microbiome. Furthermore, the gut microbiota and glucose homeostasis are known to be influenced by cholesterol metabolites like coprostanol [268, 270,271,272,273]. These results in the literature suggest that some sterols (especially plant sterols) may improve glucose homeostasis and reduce the risk of T2DM by the modulating gut microbiota through lipidomics.

Fat-soluble vitamins

Vitamin A

Vitamin A (retinol) and its enzymatic oxidation product, retinoic acid, play a role in gut health through interactions with the gut microbiome [181, 274, 275]. It has been reported that significant changes in the gut microbiome profile in acute vitamin A deficiency and the abundance of Bacteroides vulgatus increase rapidly [276]. Lv et al. (2016) concluded in their study that children with vitamin A deficiency have less microbial diversity in their gut microbiota and are more likely to experience resistant diarrhea. Another outcome of the study was the detection of less butyrate-producing Clostridia bacteria in the stools of children with vitamin A deficiency [277]. Moreover, it is stated that bacterial diversity may decrease with the decrease in butyrate-producing bacteria and the increase in opportunistic pathogens in case of vitamin A deficiency [277]. It may be considered due to the aforesaid roles that adequate dietary vitamin A intake may reduce the risk of T2DM by increasing butyrate production, which is attributed to lipidomic. To draw firm conclusions, however, is challenging due to the paucity of studies on this topic in the literature.

Vitamin D