Abstract

Background

Few efficacious physical activity interventions are successfully translated and sustained in practice. We propose a practical guide for researchers to increase the likelihood of successful implementation and scale up of physical activity interventions in practice contexts. The guide is based on two principles: (i) differences between the research and practice context can be addressed during intervention development and implementation planning by focusing on system, delivery personnel, and intervention characteristics; and (ii) early planning for implementation barriers and facilitators can improve subsequent translation into practice.

Methods

From the published literature, we identified evidence of strategies to improve research-practice translation, along with narrative descriptions of different approaches to addressing translational challenges. These, along with constructs taken from widely cited implementation outcome, process, and mechanistic models were collated and inform the guide.

Results

The resultant PRACTIS guide (PRACTical planning for Implementation and Scale-up) comprised the following four iterative steps: Step 1) Characterize the parameters of the implementation setting; Step 2) Identify and engage key stakeholders across multiple levels within the delivery system(s); Step 3) Identify contextual barriers and facilitators to implementation, and; Step 4) Address potential barriers to effective implementation.

Conclusions

A lack of practical guidance for researchers on how to effectively plan implementation and scale up of physical activity interventions prevents us moving quickly from evidence to action. We recommend that intervention development and adaptation for broad and sustained implementation be prioritized early in intervention planning and include active engagement from delivery organizations and stakeholders. The PRACTIS guide is also relevant for clinical and public health researchers in other areas of prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The past decade has seen a significant rise in the number of efficacious interventions to promote physical activity [1]. Although promising, only a minority of these interventions move from research into practice, and those that do provide limited information on sustainability or institutionalization within routine practice [2]. The movement of research to practice settings is a dynamic process that includes dissemination, implementation, and scale-up. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) define dissemination as the targeted distribution of information and intervention materials to a specific public health or clinical practice audience, with the intent to spread knowledge and the associated evidence-based interventions [3]. Implementation is the use of strategies to adopt and integrate evidence-based health interventions and change practice patterns within specific settings [3]. Scale-up is described as replicating and extending the reach of an intervention into other localities, cities, or regions [2]. Scalability describes an intervention’s potential to be delivered to an increasing number of participants or through an increasing number of settings, while retaining effectiveness [4].

There are some clear examples of dissemination [5], implementation [6], and scale-up of physical activity interventions [7, 8]. However, across three decades of physical activity intervention research, the majority of publications have been efficacy/effectiveness trials and only 3% comprised dissemination studies [4]. This continued lack of evidence for the successful institutionalisation of physical activity interventions in real-world settings, combined with unacceptably high levels of physical inactivity worldwide [9, 10], makes addressing the research-to-practice gap a significant public health priority.

Implementing and sustaining physical activity interventions in practice contexts is challenging [11, 12]. These challenges are grounded in the social-ecological differences between testing a physical activity intervention within an efficacy trial under optimal conditions to dissemination, implementation, and scale-up trials where multilevel infrastructure, resources, values, and characteristics of participants are much more variable [13,14,15]. In public health and health promotion research, dissemination is often an afterthought in the program life cycle, or conceptualized as a separate process that occurs at some nonspecific time after efficacy trials are completed [16]. Features of the implementation context which can influence the impact of an intervention (i.e. delivery capacity of implementers and organizations [17]), may also only be addressed when an intervention is considered ready for dissemination. As a result, when efficacious interventions are implemented in real-world settings, they can either fail to be adopted or report lower effect sizes, and are less likely to be sustained over time [5, 18].

There have been calls for the research community to shift the focus from small scale tightly controlled interventions to evaluating those capable of dissemination and translation [2]. Pragmatic trials [19], hybrid effectiveness-implementation trials [20] and participatory research approaches [21,22,23] are examples of study designs more suited to community and clinical-relevant research. These approaches engage key stakeholders, prioritize implementation outcomes and assess the generalizability of intervention effects. In addition, there have been calls to improve the translation of research into practice by considering a broader set of metrics, such as generalisability and sustainability, and to increase the adoption of theory-driven implementation research. For example, systems science methods (e.g. social network analysis, agent-based modelling and system dynamics) can elucidate the effects of dissemination and implementation barriers and facilitators on intervention outcomes [24]. Measurement of implementation outcomes, such as intervention feasibility and implementation cost, can be used as a proximal indicator of implementation processes, success, and sustainability [25].

There has been an increased recognition of the importance of theory-driven approaches to enhance dissemination and implementation research [26]. Extending beyond Roger’s Diffusion of Innovations Theory [27], which underpins a large body of dissemination research, there are currently over 60 published theories, models and frameworks [28]. Although methodological advances to support dissemination, implementation and scale-up trials are promising, theories, models and frameworks do not provide guidance on how best to initiate contextually-relevant processes to engage and work with typical community or clinical organizations. There is a gap in the current literature which explicitly describes ‘how to’ enact strategies to successfully translate research into practice.

The ‘how to’ guide proposed here does not purport to be a new framework or model. Rather, it draws on existing models and frameworks to address how to plan for implementation and scale-up during intervention development, testing and ongoing adaptation. We propose that prioritising factors relevant to dissemination, implementation, and scale-up early within the research process, will enable potential barriers to be addressed and their impact measured; although this remains to be tested and is beyond the scope of this paper. The PRACTIS (PRACTical planning for Implementation and Scale-up) guide outlines a structure for researchers and stakeholders, with varying levels of implementation experience and expertise, to navigate the complex considerations and decision-making processes involved in translating evidence-based interventions into practice. The purpose is to increase the likelihood that physical activity interventions can be implemented at scale and sustained in practice contexts. The challenges associated with intervention implementation and scale-up are relevant across all areas of public health prevention. For the purposes of this paper, therefore, we refer to physical activity intervention research to discuss these issues and illustrate operationalization of the PRACTIS guide.

Methods

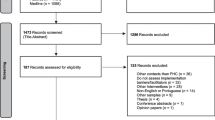

The guide was developed based on two bodies of relevant literature addressing strategies to improve research-practice translation, and constructs associated with effective implementation from widely cited implementation outcome, process, and mechanistic models.

To identify processes to improve research-practice translation, we refer to literature outlining strategies used to enhance implementation of evidence-based practices [29, 30], and the challenges of making research findings relevant to community and clinical systems [12, 31,32,33]. Common critiques include lack of representativeness of participants and intervention implementation staff, and a focus on achieving the largest effect possible, without a focus on the financial, resource, and human capital costs or even a consideration of the most likely system that would ultimately implement a physical activity intervention. Specifically, when planning an intervention, it is recommended to consider strategies to address participant reach and representativeness, organizational staff and system adoption, delivery ease and quality of implementation, and intervention sustainability [34]. Our summary of this literature encouraging an expansion of outcome assessment within dissemination, implementation, and scale-up research is included in the guide. It informed the development of a comprehensive checklist to support researcher and stakeholder planning that addresses strategies to improve implementation, dissemination and scale-up, and tools to aid the decision making processes used to develop partnerships with systems that will ultimately apply research findings within practice.

To identify constructs associated with effective implementation, we referred to a second body of literature summarizing implementation theories, models and frameworks [26, 28]. Frameworks were chosen for inclusion in the PRACTIS guide based on the following criteria: (i) a typology of constructs associated with effective dissemination, implementation, and/or scale-up; (ii) specifying causal multi-level associations with implementation effectiveness; (iii) developed based on either empirical results or unifying constructs from existing conceptual frameworks/theories; (iv) previous application in physical activity and preventive health research and; (v) applicability to a variety of implementation settings. Three widely cited explanatory frameworks were identified: the Interactive Systems Framework (ISF) [17], the ecological framework for effective implementation [14], and the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [35].

Constructs within each framework were individually tabulated and grouped based on five higher order domains described within the frameworks (implementer characteristics; organizational characteristics; intervention characteristics; community characteristics and; process of implementation). We compared and contrasted the constructs and propositions from each of these frameworks, and identified overlapping constructs based on a shared definition or meaning (i.e. ‘skills’ in the ISF and ‘skill proficiency’ in Durlak and Dupre’s ecological framework), and a comparable level of impact (i.e. organizational or community level). A total of 85 individual constructs existed across the three frameworks, which resulted in 72 overlapping ‘common’ constructs, to produce a compilation of multi-level barriers to implementation (see Additional file 1 which presents the framework constructs). As the five higher order domains from these frameworks span all levels of the social-ecological model, they were used as areas of emphasis throughout our proposed guide.

A draft of the guide was piloted among physical activity and nutrition experts (n = 9) during an Implementation Science workshop held at an Australian University in October 2017. Registration was voluntarily and there were no costs to participate. Feedback during this workshop led to revisions to the explanatory text within the guide, to improve use ability and application of the guide in practice.

The proposed PRACTIS guide

The guide is based on the following underlying principles. First, multi-level differences that exist between the research (intervention testing) and practice (intervention implementation) context can be best addressed during early intervention planning that engages stakeholders. Second, early anticipation and planning for barriers to intervention implementation, typical in community or clinical settings, can improve the translation of evidence to practice.

The guide describes a series of steps outlining how best to plan the dissemination, implementation, and scale-up of physical activity interventions for clinical and public health settings: Step 1) Characterize the parameters of the implementation setting; Step 2) Identify and engage key stakeholders across multiple levels within the delivery system(s); Step 3) Identify contextual barriers and facilitators to implementation, and; Step 4) Address potential barriers to effective implementation. Characteristics of the potential implementation context feature as the foremost component of the guide. The ‘implementation context’ refers to the physical, social and cultural environment where the physical activity intervention would be integrated. The implementation context also includes who, what and how the intervention would be delivered if research funding has ceased. Characteristics of the implementation context (Step 1) underpin all decisions and strategies to improve implementation planning and intervention testing (Steps 2-4). Figure 1 presents an overarching process flowchart of the steps required.

The process begins by engaging key stakeholders to consider: the population who will receive or deliver the intervention; the place where the intervention will be implemented; the intervention and implementation process; the provisions needed for implementation; and the principles underpinning scale up. Optimally, iterative evaluation is used to refine implementation strategies for dissemination, for sustained implementation, and to assess outcomes when scale-up is complete.

Outcomes from Steps 1- 4 are likely to contribute to more effective strategies for intervention implementation, and also to assessments of implementation-related outcomes (e.g. reach, delivery quality, acceptability, compatibility, costs). Each Step considers multi-level influences on implementation of physical activity interventions in practice settings. Common constructs identified from within key implementation frameworks inform potential barriers in Step 3. Formative and process evaluation approaches [36, 37], including intervention testing methodologies [12, 31, 34], inform strategies to address potential barriers to effective implementation in Step 4.

We present these steps as a linear process of repeated cycles, but acknowledge that steps are not mutually exclusive and the process is iterative, thus will reflect learnings from systematic implementation efforts. For example, identifying barriers in Step 3 may lead to revisiting how the parameters of the implementation setting are characterized. The Steps may occur sequentially, include overlapping activities, and/or in a different order depending on the complexity of the intervention and setting. The Steps should be followed as contextually appropriate.

Step 1: Characterize parameters of the implementation setting

Step 1 describes features of the proposed implementation setting, pinpointing gaps in the planning process. Early familiarization with characteristics of the real-world implementation context promotes planning and accountability for future implementation, and may enhance implementation efforts. Table 1 presents a 15-item checklist containing 38 questions to guide researcher and stakeholder familiarisation with the potential implementation setting. Researchers and stakeholders can complete the checklist independently, to enable differences in perspectives and expectations regarding implementation to be highlighted and addressed. Questions within this checklist can also be used to guide researcher-stakeholder discussions on target areas of importance (Step 2). As disparities exist in physical activity participation [38], special consideration is given across the checklist to reflect on high need populations that may be more at risk of physical inactivity due to particular disparities. The process within this guide is iterative and therefore some checklist items may only be answerable after stakeholder consultation or intervention piloting, for example. The checklist should be used to identify gaps or areas for further exploration throughout the implementation and scale up process as new information emerges.

Checklist items correspond to key issues relating to intervention adoption, delivery and sustainability in practice, potential scalability of the intervention and implementation process, and important multi-level contextual characteristics. Checklist responses contribute to describing: who/how many people the intervention will reach and which individuals will be involved/required for effective implementation (i.e. People); what settings/organizations will be involved/required (i.e. Place); how the intervention or implementation process will occur (i.e. Process); what resources may be necessary to achieve this (i.e. Provisions); and the underlying principles of the intervention (e.g. individual behavior change) and implementation process (e.g. building capacity for implementation) that will be scaled-up (i.e. Principles). Table 2 presents the descriptive criteria for the ‘five P’s’.

Outcomes from the five P’s inform: (i) actions required to make the intervention implementable and/or scalable; (ii) potential barriers to effective implementation and scale-up; and (iii) formative evaluation strategies and/or process measures that may improve implementation and scale-up. Researchers may complete the checklist independently or in collaboration with stakeholders identified in Step 2, however responses should be presented to stakeholders for validation or refinement.

Step 2: Identify and engage key stakeholders across multiple levels within the delivery system(s)

The aim of Step 2 is to identify and engage with key stakeholders (individuals or organizations) in interventions. Irrespective of the target setting, participatory research with stakeholders can facilitate implementation and sustainability of physical activity interventions, for example in community [39] and school settings [40], and scale up of physical activity interventions requires partnerships beyond the health sector [2]. An intervention that considers stakeholder priorities may lead to improved engagement and involvement [41], as implementation will be optimized through an understanding of an intervention’s likely or potential ‘fit’. Figure 2 presents a decision tree to facilitate stakeholder identification.

To operationalize the decision tree (Fig. 2), firstly identify stakeholders (individuals or organizations) that will: (i) fund and/or have overarching responsibility or ‘ownership’ for the intervention; (ii) disseminate (distribute) the intervention to the target setting and population; (iii) host and/or deliver the intervention either in the target setting or to the target population; and (iv) receive the intervention (target user). Stakeholder discussions should aim to increase awareness of the research, practice and policy activities involved in implementation and scale up, and facilitate effective information exchange, collaboration and use of existing knowledge [42]. Strategies for effective stakeholder engagement and communication should feature throughout implementation, to ensure transparency in roles and responsibilities, and agreement on outcome expectations. Depending on the context and scale of implementation (i.e. targeting 100 or 10,000 people), stakeholders may represent multiple distinct organizations or multiple distinct roles within any one organization. Depending on the type of intervention, stakeholders may also represent single or multiple ‘systems’ (i.e. health, education, transport systems).

Strategies and resources required to engage these stakeholders will therefore differ based on the type of intervention, scale of implementation and number of systems that will be involved in delivery. Outcomes from the decision tree will highlight opportunities to strengthen or seek new stakeholder relationships, and possible limitations if engagement and/or participation is suboptimal.

Step 3: Identify contextual barriers and facilitators to implementation

The purpose of Step 3 is to identify potential contextual barriers and facilitators to implementation and scale-up, to enhance integration of research findings into practice [32]. Figure 3 presents an ecological model depicting 45 of the 72 overlapping ‘common’ constructs, identified from the three frameworks. The remaining 27 ‘common’ constructs are not depicted in Fig. 3 for pragmatic reasons, as they either underpin another CFIR construct presented in Fig. 3 (see italicized constructs in Additional file 1) or are constructs that influence all levels of the ecological model. Constructs influencing all ecological levels include intervention characteristics (i.e. intervention’s legitimacy, quality/validity of evidence, adaptability, trialability, complexity, compatibility, relative advantage, design quality and cost) [14, 35], and the process of implementation (i.e. intervention specific and general capacity building [14, 17], and planning, engaging, executing, reflecting and evaluating the implementation process [35]).

The purpose of Fig. 3 (and Additional file 1) is to illustrate the breadth of commonly occurring factors that may require exploration with stakeholders during implementation planning and intervention testing. This compilation could be useful in pinpointing aspects of the intervention design and implementation/scale-up plan that may warrant refinement or further testing. The compilation can also be used as a reference tool when completing the 15-item checklist in Step 1, and provide a pictorial representation of potential challenges to implementation when engaging with stakeholders in Step 2.

Step 4: Address potential barriers to effective implementation

The purpose of Step 4 is to address potential barriers to effective implementation identified in Step 3, through refinements to the intervention and implementation process with stakeholders, and/or formal assessment of their impact on implementation and intervention outcomes through research testing. Table 3 presents example strategies to be incorporated during intervention and implementation planning (formative evaluation) and/or during intervention testing (process and outcome evaluation), which may improve research-practice translation.

Translational formative evaluation [43] can include practice-based activities (i.e. strategic partnering with stakeholders, community members, decision-makers and opinion leaders associated with future implementation and scale-up), and research-based activities (i.e. needs assessments, feasibility and pilot trials) to assess local needs, values and intervention compatibility with the local context. Process measures are assessed in parallel to intervention testing, and can elucidate underlying mechanisms in the intervention context that may explain outcomes or how to move from research to practice [44]. Example ways of using formative and process evaluation to inform implementation and scale-up of physical activity interventions are described in the following section.

Operationalizing the PRACTIS guide

To exemplify operationalization of the PRACTIS guide, we retrospectively applied the guide to four evidence-based physical activity interventions previously translated into clinical and community settings (see Additional file 2 for a summary of these case studies). To illustrate how outcomes from Step 1 correspond to implementation planning, we present information from these example interventions against the criteria of the five P’s (Table 2). The example interventions have all been adopted and implemented at a state or national level in the United States or Australia and were designed with implementation in mind. These interventions were chosen as they adopted a range of intervention strategies and targeted varying populations and settings, for example: early childcare centers (Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care [NAP SACC] [45]), the school setting (the Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health [CATCH] [46, 47]), and community-based/clinical healthcare contexts (Healthy Living after Cancer [HLaC] [48] and Move More [49]). Findings from earlier trials of NAP SACC have led to the development of an online delivery version to extend the program’s reach (‘Go NAP SACC’ [50]). For the purpose of this paper, we only draw on early publications detailing original study/intervention design and implementation planning processes.

The use of case studies to illustrate application of the guide highlights the variation in coverage of the four Steps. Consistent across all intervention examples, was that information gathered on the ‘five P’s’ to determine the parameters of the implementation context was used in each of the subsequent Steps. Each intervention adopted a participatory and collaborative approach to the co-production of evidence, drawing on stakeholders to guide the research design and implementation planning process, in addition to having input into intervention materials and resources. While these case studies are only briefly presented here and based on the available published descriptions of implementation planning, they highlight the strengths of a comprehensive, multilevel exploration of barriers and resolutions, and inclusion of formative and process evaluation to plan for implementation and scale-up.

Discussion

Challenges and recommendations to improve intervention dissemination and implementation are well documented [31, 34, 51]. What is less well established is how researchers should apply this knowledge pragmatically to improve the implementation of physical activity interventions in real-world settings. The PRACTIS guide addresses this gap and demonstrates how to map features of the implementation setting, identify and engage important stakeholders, and anticipate and address potential barriers and facilitators to effective implementation and scale up.

It is assumed that interventions must first demonstrate efficacy under controlled conditions in a randomised trial, then effectiveness under real-world conditions, and finally evidence for potential scale up and subsequent dissemination [52]. In the context of behavioral interventions in particular, this sequential progression from efficacy to dissemination has been criticised on the basis that efficacy trials tell us little about the generalizability of interventions [53,54,55]. There is also the implicit assumption that dissemination and implementation may only be considered later in the research process. Contrary to Flay et al. (2005), we propose that conceptual and methodological issues in translation, constructs identified in implementation frameworks, and strategies to improve the translation of physical activity interventions, can and should be considered from the beginning of intervention development. Starting with the end application in mind can strengthen translation efforts [34], address challenges of dissemination [16], and may be linked to more successful scale-up efforts [56]. Engaging practice professionals and other stakeholders early in intervention planning may also strengthen research translation efforts and enhance application of the proposed steps [15].

The guide is also applicable when planning scaled-up interventions in other areas of public health prevention. Unlike discrete intervention trials targeting small populations, at scale the impact of system-level factors such as bureaucratic cultures, political environments and global trends may be amplified [57]. Funding and resources are also more likely to be sourced from within user organizations or the broader delivery systems (i.e. health, education, political), until intervention costs become integrated into national and local budgets [58]. Intervention flexibility and contextual adaptation are critical credentials for the widespread adoption of interventions across diverse sociocultural settings [56]. Irrespective of the scale of implementation, adaptation can be both desirable (such as adapted intervention modality to increase reach) and undesirable (such as a lower dose of delivery due to conflicting demands) [59]. Ascertaining intervention flexibility and associated effectiveness following contextual adaptation, should feature within all public health intervention planning. Successful scale up may depend on the interaction between an intervention’s intensity and the resources available within the delivery setting [5, 60]. The PRACTIS guide is hypothesized to result in intervention and implementation adaptations that align more closely to resources available within the delivery context.

Real-world implementation is an evolving process that mirrors constant changes in the physical and social environment. As the intervention and research progresses, and new information emerges, this guide may need to be revisited. Addressing all potential barriers to implementation (Step 3) may neither be feasible nor necessary, and decisions in Step 4 are likely to be informed by barrier implications, researcher capacity and pragmatism. For example, system-level barriers such as existing policies which conflict with intervention objectives or a political system that does not prioritize preventive health, will require complex resolutions that are not immediately ‘solvable’. Researcher capability to respond to a barrier may therefore be limited, irrespective of well-meaning intentions or strong supportive evidence.

Abandonment (or de-implementation) of health interventions should occur, for example, when evidence contradicts existing practices [61]. However, de-implementation can depend on multiple factors, beyond scientific evidence, such as cultural, societal values and inertia [61]. For example, interventions that are ‘designed for scalability’ at an individual level (e.g. using an online modality to facilitate broad reach among target users) or have demonstrated evidence for effectiveness, may still fail to achieve sustained stakeholder support for implementation, due to entrenched organizational or system level factors. We hypothesize that de-implementation is best achieved when alternative options are available and a participatory approach is used to match intervention strategies to organizational resources as described in the PRACTIS guide. Following the guide may also help identify circumstances when further testing and/or adaptation of interventions should cease, or when abandon of implementation is more viable.

This guide is not without limitations and the complexities and costs of implementation within single and multiple systems should not be understated. To date, the majority of implementation research has emanated from clinical and health service contexts and it is unclear if such evidence is transferable to physical activity intervention research where the ‘place’ of delivery extends to a wide variety of community settings. Solutions to implementation barriers are also likely to differ by settings, multicomponent implementation strategies may be suited to different stages of implementation [30], and the appropriateness and effectiveness of strategies may vary by translation phase [62]. It is also less clear whether implementation variables should be prioritized in specific contexts, and which implementation strategy is best under which circumstance. Future research which investigates these core issues is needed. We encourage researchers to apply this population-focused guide and critically evaluate the proposed process.

Conclusions

Complex characteristics of real-world implementation settings and the multilevel barriers to effective implementation are two of the many challenges faced when translating evidence-based interventions into practice. Those who are interested in translating physical activity promotion research into sustained practice are encouraged to use, and may benefit from, the PRACTIS guide to inform and operationalize their work. This guide is also relevant for clinical and public health researchers in other areas of prevention, to translate evidence-based interventions into real-world settings.

Abbreviations

- CFIR:

-

Consolidated framework for implementation research

- ISF:

-

Interactive systems framework

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- PE:

-

Physical education

- PRACTIS:

-

PRACTical planning for Implementation and scale-up

References

Heath GW, Parra DC, Sarmiento OL, Andersen LB, Owen N, Goenka S, Montes F, Brownson RC. Evidence-based intervention in physical activity: lessons from around the world. Lancet. 2012;380:272–81.

Reis RS, Salvo D, Ogilvie D, Lambert EV, Goenka S, Brownson RC. Scaling up physical activity interventions worldwide: stepping up to larger and smarter approaches to get people moving. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1337–48.

Research Dissemination and Implementation (R18) Grants [https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/grants-and-training/policies-and-guidelines/research-dissemination-and-implementation-r18-grants].

Milat AJ, Bauman AE, Redman S, Curac N. Public health research outputs from efficacy to dissemination: a bibliometric analysis. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:1–9.

Harden SM, Johnson SB, Almeida FA, Estabrooks PA. Improving physical activity program adoption using integrated research-practice partnerships: an effectiveness-implementation trial. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7:28–38.

Waqa G, Moodie M, Schultz J, Swinburn B. Process evaluation of a community-based intervention program: healthy youth healthy communities, an adolescent obesity prevention project in Fiji. Glob Health Promot. 2013;20:23–34.

de Silva-Sanigorski AM, Bolton K, Haby M, Kremer P, Gibbs L, Waters E, Swinburn B. Scaling up community-based obesity prevention in Australia: background and evaluation design of the health promoting communities: being active eating well initiative. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:65.

Naylor P, Macdonald H, Reed K, McKay H. Action schools! BC: a socioecological approach to modifying chronic disease risk factors in elementary school children. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3:A60.

Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, Guthold R, Haskell W, Ekelund U. Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet. 2012;380:247–57.

Kohl HW, Craig CL, Lambert EV, Inoue S, Alkandari JR, Leetongin G, Kahlmeier S. The pandemic of physical inactivity: global action for public health. Lancet. 2012;380:294–305.

Estabrooks PA, Smith-Ray RL, Dzewaltowski DA, Dowdy D, Lattimore D, Rheaume C, Ory MG, Bazzarre T, Griffin SF, Wilcox S. Sustainability of evidence-based community-based physical activity programs for older adults: lessons from active for life. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2011;1:208–15.

Rabin BA, Brownson RC, Kerner JF, Glasgow RE. Methodologic challenges in disseminating evidence-based interventions to promote physical activity. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31:S24–34.

Chaudoir SR, Dugan AG, Barr CH. Measuring factors affecting implementation of health innovations: a systematic review of structural, organizational, provider, patient, and innovation level measures. Implement Sci. 2013;8:22.

Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41:327–50.

Estabrooks PA, Glasgow RE. Translating effective clinic-based physical activity interventions into practice. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31:S45–56.

Bopp M, Saunders RP, Lattimore D. The tug-of-war: Fidelity versus adaptation throughout the health promotion program life cycle. J Prim Prev. 2013;34:193–207.

Wandersman A, Duffy J, Flaspohler P, Noonan R, Lubell K, Stillman L, Blachman M, Dunville R, Saul J. Bridging the gap between prevention research and practice: the interactive systems framework for dissemination and implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41:171–81.

Scheirer MA, Dearing JW. An agenda for research on the sustainability of public health programs. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:2059–67.

Peters DH, Tran NT, Adam T: Implementation research in health: a practical guide.; 2013.

Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. 2012;50:217–26.

Jull J, Giles A, Graham ID. Community-based participatory research and integrated knowledge translation: advancing the co-creation of knowledge. Implement Sci. 2017;12:150.

Mercer S, DeVinney B, Fine L, Green L, Dougherty D. Study designs for effectiveness and translation research :identifying trade-offs. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:139–54.

Estabrooks PA, Bradshaw M, Dzewaltowski DA, Smith-Ray RL. Determining the impact of walk Kansas: applying a team-building approach to community physical activity promotion. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36:1–12.

Burke JG, Lich Hassmiller K, Neal Watling J, Meissner HI, Yonas M, Mabry PL. Enhancing dissemination and implementation research using systems science methods. Int J Behav Med. 2014:1–9.

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, Griffey R, Hensley M. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2011;38

Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Science: IS. 2015;10:53.

Rogers E. Diffusion of innovations. 5th ed. New York: Free Press; 2003.

Tabak RG, Khoong EC, Chambers DA, Brownson RC. Bridging research and practice: models for dissemination and implementation research. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:337–50.

Leeman J, Birken SA, Powell BJ, Rohweder C, Shea CM. Beyond “implementation strategies”: classifying the full range of strategies used in implementation science and practice. Implement Sci. 2017;12:125.

Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. 2013;8:139.

Marchand E, Stice E, Rohde P, Becker CB. Moving from efficacy to effectiveness trials in prevention research. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49:32–41.

Glasgow R, Emmons KM. How can we increase translation of research into practice? Types of evidence needed. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:413–33.

Green L, Glasgow R. Evaluating the relevance, generalization, and applicability of research: issues in external validation and translation methodology. Eval Health Prof. 2006;29:126–53.

Klesges LM, Estabrooks PA, Dzewaltowski DA, Bull SS, Glasgow RE: Beginning with the application in mind: designing and planning health behavior change interventions to enhance dissemination. Ann Behav Med 2005, 29 Suppl:66-75.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:1–15.

Bauman A, Nutbeam D. Evaluation in a Nutshell. A practical guide to the evaluation of health promotion programs. 2 edn. North Ryde: McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd; 2013.

Stetler CB, Legro MW, Wallace CM, Bowman C, Guihan M, Hagedorn H, Kimmel B, Sharp ND, Smith JL. The role of formative evaluation in implementation research and the QUERI experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:S1–8.

Gordon-Larsen P, Nelson M, Page P, Popkin B. Inequality in the built environment underlies key health disparities in physical activity and obesity. Pediatrics. 2006;117:417–24.

Derose K, Marsh T, Mariscal M, Pina-Cortez S, Cohen DA. Involving community stakeholders to increase park use and physical activity. Prev Med. 2014;64:14–9.

Haggis C, Sims-Gould J, Winters M, Gutteridge K, McKay HA. Sustained impact of community-based physical activity interventions: key elements for success. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:892.

Trompette J, Kivits J, Minary L, Cambon L, Alla F. Stakeholders' perceptions of transferability criteria for health promotion interventions: a case study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1134.

Norton WE, McCannon CJ, Schall MW, Mittman BS. A stakeholder-driven agenda for advancing the science and practice of scale-up and spread in health. Implement Sci. 2012;7:118.

O'Hara BJ, Phongsavan P, King L, Develin E, Milat AJ, Eggins D, King E, Smith J, Bauman AE. 'Translational formative evaluation': critical in up-scaling public health programmes. Health Promot Int. 2013;29:38–46.

Grant A, Treweek S, Dreischulte T, Foy R, Guthrie B. Process evaluations for cluster-randomised trials of complex interventions: a proposed framework for design and reporting. Trials. 2013;14:15.

Ammerman AS, Ward DS, Benjamin SE, Ball SC, Sommers JK, Molloy M, Dodds JM. An intervention to promote healthy weight: nutrition and physical activity self-assessment for child care (NAP SACC) theory and design. Prev Chronic Dis. 2007;4:A67.

Perry C, Stone E, Parcel G, Ellison R, Nader P, Webber L, Luepker R. School-based cardiovascular health promotion: the child and adolescent trial for cardiovascular health (CATCH). J Sch Health. 1990;60:406–13.

McGraw SA, Stone EJ, Osganian SK, Elder JP, Perry CL, Johnson CC, Parcel GS, Webber LS, Luepker RV: Design of process evaluation within the child and adolescent trial for cardiovascular health (CATCH). Health Educ Q 1994, Suppl 2:S5-26.

Eakin EG, Hayes SC, Haas MR, Reeves MM, Vardy JL, Boyle F, Hiller JE, Mishra GD, Goode AD, Jefford M, et al. Healthy living after Cancer: a dissemination and implementation study evaluating a telephone-delivered healthy lifestyle program for cancer survivors. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:992.

Estabrooks PA, Smith-Ray RL, Almeida FA, Hill J, Gonzales M, Schreiner P, Van Den Berg R. Move more: translating an efficacious group dynamics physical activity intervention into effective clinical practice. Int J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2011;9:4–18.

Ward DS, Vaughn AE, Mazzucca S, Burney R. Translating a child care based intervention for online delivery: development and randomized pilot study of go NAPSACC. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:891.

Kessler R, Glasgow RE. A proposal to speed translation of healthcare research into practice: dramatic change is needed. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:637–44.

Flay BR, Biglan A, Boruch RF, Castro FG, Gottfredson D, Kellam S, Mościcki EK, Schinke S, Valentine JC, Ji P. Standards of evidence: criteria for efficacy, effectiveness and dissemination. Prev Sci. 2005;6:151–75.

Glasgow R, Lichtenstein E, Marcus A. Why Don't we see more translation of health promotion research to practice? Rethinking the efficacy-to-effectiveness transition. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1261–7.

Estabrooks PA, Gyurcsik NC. Evaluating the impact of behavioral interventions that target physical activity: issues of generalizability and public health. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2003;4:41–55.

Dzewaltowski DA, Estabrooks PA, Glasgow RE. The future of physical activity behavior change research: what is needed to improve translation of research into health promotion practice? Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2004;32:57–63.

World Health Organization: Beginning with the end in mind: planning pilot projects and other programmatic research for successful scaling up. Geneva: Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2011.

Milat AJ, Bauman A, Redman S. Narrative review of models and success factors for scaling up public health interventions. Implement Sci. 2015;10:113.

Simmons R, Shiffman J. Scaling up health service innovations: a framework for action. In: Simmons RFP, Ghiron L, editors. Scaling up health service delivery. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. p. 1–30.

Rogers EM. Diffusion of preventive innovations. Addict Behav. 2002;27:989–93.

Johnson SB, Harden SM, Estabrooks PA. Uptake of evidence-based physical activity programs: comparing perceptions of adopters and nonadopters. Transl Behav Med. 2016;6:629–37.

Prasad V, Ioannidis JPA. Evidence-based de-implementation for contradicted, unproven, and aspiring healthcare practices. Implementation Science : IS. 2014;9:1–1.

Aarons GA, Green AE, Palinkas LA, Self-Brown S, Whitaker DJ, Lutzker JR, Silovsky JF, Hecht DB, Chaffin MJ. Dynamic adaptation process to implement an evidence-based child maltreatment intervention. Implement Sci. 2012;7:32.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Implementation Science workshop participants who provided feedback on a draft of the PRACTIS guide, and the anonymous reviewers whose comments helped refine the manuscript.

Funding

EE is supported by an NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship. PE received funding from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences – Great Plains IDeA Clinical and Translational Research Network (U54 GM115458-01). AT is supported by a Future Leader Fellowship from the National Heart Foundation of Australia (100046). EE, AT and JS received funding from the NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence (APP ID: 1057608), which was used to support HK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HK conceptualised and developed the guide, leading writing of the manuscript. EE, PE and AB critically revised the concepts, content and structure of the guide. AT & JS contributed to initial conceptualisation and development of the guide structure. All authors critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content, and read and approved the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Overlapping framework constructs. Table presenting constructs from the three implementation frameworks and corresponding overlap in constructs between frameworks. (DOCX 21 kb)

Additional file 2:

Example operationalization. Table summary of four physical activity intervention illustrating operationalization of the PRACTIS guide (DOCX 25 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Koorts, H., Eakin, E., Estabrooks, P. et al. Implementation and scale up of population physical activity interventions for clinical and community settings: the PRACTIS guide. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 15, 51 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0678-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0678-0