Abstract

Background

Research and practice partnerships have the potential to enhance the translation of research findings into practice.

Purpose

This paper describes such a partnership in the development of Walk Kansas (WK) and highlights individual and organizational level outcomes.

Method

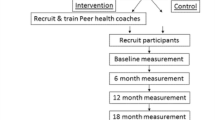

Phase 1 examined: (a) the reach of WK, (b) physical activity changes, and (c) maintenance of physical activity changes 6 months after the program was completed. Phase 2 explored WK adoption and sustainability over 5 years.

Results

WK attracted a large number of participants who were more likely to be female, more active, and older than the adult population within the counties where they resided. Inactive or insufficiently active participants at baseline experienced significant increases in both moderate (p < 0.001) and vigorous (p < 0.001) physical activity. A random selection of participants who were assessed 6 months post-program did not demonstrate a significant decrease in moderate or vigorous activity between program completion and 6-month follow-up. The number of counties adopting the program increased across years, peaking at 97 in 2006 and demonstrated the sustainability of the WK over 5 years.

Conclusions

WK is effective, has a broad reach, and enables participants to maintain increased activity. It also shows promise for broad adoption and sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Fundamental to Preventing Disease. Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; 2002.

US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Pittsburgh, PA: Superintendent of Documents; 1996.

US Department of Health and Human Services. Promoting better health for young people through physical activity and sports: A report to the President from the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Education. 2000.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity and Older Americans: Benefits and Strategies. CDC 2002.

Mokdad AH, Marks JF, Stroup DF, Gerdes DA. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. J Am Med Assoc. 2004; 291: 1238–1245.

McGinnis JM, Foege WH. The immediate versus the important. J Am Med Assoc. 2004; 291: 1263–1264.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Early release of selected estimates based on data from the 2003 National Health Interview Survey. National Health Interview Survey 2004; pp. 34–36. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis.

Kahn EB, Ramsey LT, Brownson RC, Heath GW, Howze EH, Powell KE, Stone EJ, Rajab MW, Corso P. The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity: A systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2002; 224s: 73–107.

Estabrooks PA, Gyurcsik NC. Evaluating the public health impact of physical activity interventions. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2003; 4: 41–55.

Flay BR. Efficacy and effectiveness trials (and other phases of research) in the development of health promotion programs. Prev Med. 1986; 15: 451–474.

Estabrooks P, Dzewaltowski DA, Glasgow RE, Klesges LM. School-based health promotion: Issues related to translating research into practice. J Sch Health. 2003; 7321: 28.

Bull SS, Gillette C, Glasgow RE, Estabrooks P. Worksite health promotion research: To what extent can we generalize the results and what is needed to translate research to practice? Health Educ Behav. 2003; 30: 537–549.

Dzewaltowski DA, Estabrooks PA, Klesges LM, Bull SS, Glasgow RE. Behavior change research in community settings: How generalizable are the results? Health Promot Int. 2004; 192: 235–245.

Glasgow RE, Bull SS, Gillette C, Klesges LM, Dzewaltowski DA. Behavior change intervention research in health care settings: A review of recent reports, with emphasis on external validity. Am J Prev Med. 2002; 231: 62–69.

Glasgow RE, Klesges LM, Dzewaltowski DA, Bull SS, Estabrooks PA. The future of health behavior change research: What is needed to improve translation of research into health promotion practice? Annals Behav Med. 2004; 27: 3–12.

O’Toole TP, Aaron KF, Chin MH, Horowitz C, Tyson F. Community-based participatory research. J Gen Intern Med. 2003; 18: 592–594.

Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, Gartlehner G, Lohr KN, Griffith D, Rhodes S, Samuel-Hodge C, Maty S, Lux L, Webb LA, Sutton SF, Swinson T, Jackman A, Whitener L. Community-Based Participatory Research: A Summary of the Evidence. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality; 2004.

Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998; 19: 173–202.

Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th ed. New York, NY: Free Press; 2003.

United States Congress. Smith-Lever Act of May 8, 1914. Smith-Lever Act 1914; Chapter 78.

Kansas State University Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension Service. Handbook for County Extension Councils and District Governing Bodies. 1998.

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999; 89: 1322–1327.

Wilcox S, Castro C, King AC, Housemann RA, Brownson RC. Determinants of leisure time physical activity in rural compared with urban older and ethnically diverse women in the United States. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000; 549: 667–672.

McMurray RG, Harrell JS, Bangdiwala SI, Deng S. Cardiovascular disease risk factors and obesity of rural and urban elementary school children. J Rural Health. 1999; 154: 365–374.

Patterson PD, Moore CG, Probst JC, Shinogle JA. Obesity and physical activity in rural America. J Rural Health. 2004; 202: 151–159.

Green LW. Participatory Research in Health Promotion. British Columbia: Royal Society of Canada; 1995.

Carron AV, Spink KS. Team building in an exercise setting. Sport Psychol. 1993; 7: 8–18.

Rejeski WJ, Brawley LR, Brubaker PH, Ambrosius WT, Fox LD, Focht BP, Foy CG. Older adults with chronic disease: Benefits of group-mediated counseling in the promotion of physically active lifestyles. Health Psychol. 2003; 224: 414–423.

Brawley LR, Rejeski WJ, Lutes L. A group-mediated cognitive-behavioral intervention for increasing adherence to physical activity in older adults. J Appl Biobehav Res. 2000; 51: 47–65.

Estabrooks PA, Carron AV. Group cohesion in older adult exercisers: Prediction and intervention effects. J Behav Med. 1999; 226: 575–588.

Spink KS, Carron AV. The effects of team building on the adherence patterns of female exercise participants. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1993; 15: 39–49.

Estabrooks PA, Fox EH, Doerksen SE, Bradshaw MH, King AC. Participatory research to promote physical activity at congregate meal sites. J Aging Phys Act. 2004; 132: 121–144.

Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, O’Brien WA, Bassett DR, Schmitz KH, Emplaincourt PO, Jacobs DR, Leon AS. Compendium of physical activities: An update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000; 329: S498–S516.

King AC, Rejeski WJ, Buchner DM. Physical activity interventions targeting older adults: A critical review and recommendations. Am J Prev Med. 1998; 154: 316–333.

Hillsdon M, Thorogood M, Anstiss T, Morris J. Randomised controlled trials of physical activity promotion in free living populations: A review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995; 49: 448–4453.

Abrams D, Orleans CT, Niaura RS, Goldstein MG, Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. Integrating individual and public health perspectives for treatment of tobacco dependence under managed health care: A combined stepped-care and matching model. Annals Behav Med. 1996; 184: 290–304.

King AC. The coming of age of behavioral research in physical activity. Annals Behav Med. 2001; 234: 227–228.

Macera CA, Pratt C. Public health surveillance of physical activity. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2000; 712: 97–103.

Macera CA, Ham SA, Jones DA, Kimsey CD, Ainsworth BE, Neff LJ. Limitations on the use of a single screening question to measure sedentary behavior. Am J Public Health. 2001; 91: 2012–2021.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2001 State Summary Data Kansas: Physical Activity. United States Department of Health and Human Services 2004; Available from: URL: http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/PASurveillance/StateSumResultV.asp?Year=2001&State = 19

Carron AV, Hausenblas HA, Eys MA. Group Dynamics in Sport. 3rd ed. Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology, Inc; 2005.

Acknowledgment

We express our thanks and acknowledge the work of the participatory group of agents, community members, and other staff members who participated in the design, implementation, and continued delivery of Walk Kansas. In particular, we thank Sharolyn Flaming-Jackson for her excellent insight, generosity, leadership, and dedication to promote physical activity across Kansas. Also, we thank Elizabeth Wyrill for her enthusiasm and dedication. We also acknowledge research support from Kansas Department of Social and Rehabilitative Services.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Estabrooks, P.A., Bradshaw, M., Dzewaltowski, D.A. et al. Determining the Impact of Walk Kansas: Applying a Team-Building Approach to Community Physical Activity Promotion. ann. behav. med. 36, 1–12 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-008-9040-0

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-008-9040-0