Abstract

Background

Given evidence shows physical activity, a healthful diet and weight management can improve cancer outcomes and reduce chronic disease risk, the major cancer organisations and health authorities have endorsed related guidelines for cancer survivors. Despite these, and a growing evidence base on effective lifestyle interventions, there is limited uptake into survivorship care.

Methods/Design

Healthy Living after Cancer (HLaC) is a national dissemination and implementation study that will evaluate the integration of an evidence-based lifestyle intervention for cancer survivors into an existing telephone cancer information and support service delivered by Australian state-based Cancer Councils. Eligible participants (adults having completed cancer treatment with curative intent) will receive 12 health coaching calls over 6 months from Cancer Council nurses/allied health professionals targeting national guidelines for physical activity, healthy eating and weight control. Using the RE-AIM evaluation framework, primary outcomes are service-level indicators of program reach, adoption, implementation/costs and maintenance, with secondary (effectiveness) outcomes of patient-reported anthropometric, behavioural and psychosocial variables collected at pre- and post-program completion. The total participant accrual target across four participating Cancer Councils is 900 over 3 years.

Discussion

The national scope of the project and broad inclusion of cancer survivors, alongside evaluation of service-level indicators, associated costs and patient-reported outcomes, will provide the necessary practice-based evidence needed to inform future allocation of resources to support healthy living among cancer survivors.

Trial registration

Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTR) - ACTRN12615000882527 (registered on 24/08/2015)

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cancer survivorship in Australia

Five-year survival rates for the majority of cancers have steadily improved in Australia over the past decades, from 47 % to 66 % between the periods 1982–1987 and 2006–2010, with rates for the most prevalent cancers - prostate, breast and colorectal cancers - now being 92 %, 89 % and 66 %, respectively [1, 2]. These improvements in survival are also mirrored across other developed countries [3]. However, cancer survivorship brings with it increased risk of cancer recurrence, second primaries, persistent side-effects of treatment, functional decline and co-morbid chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes [4–7]. To mitigate these risks and improve the longer-term well-being of cancer survivors, national cancer organisations recommend that cancer survivors engage in regular physical activity, eat a healthy diet and keep their weight within a healthy range [8–10]. Yet, the majority of cancer survivors do not meet these lifestyle recommendations; over 50 % are overweight or obese, over 50 % do not meet physical activity recommendations, and 90 % do not meet dietary guidelines [11–13]. Further, declines in activity and weight gain are common post-cancer treatment [14–16]. Despite a strong desire on the part of most cancer survivors for advice and support regarding healthy lifestyles [17], such assistance is not routinely offered as part of survivorship care [17–19].

Lifestyle interventions for cancer survivors

Initial research in lifestyle interventions in cancer survivors emphasised efficacy trials of highly selected participants (primarily women with early stage breast cancer), with strictly controlled intervention protocols delivered in supervised, clinic settings [20–25]. Over the past decade, the number of trials of lifestyle interventions in cancer survivor groups other than breast has expanded, demonstrating their safety, feasibility and efficacy in gynaecological cancers, prostate, colorectal, and lung cancers [26–42]. With the efficacy of such interventions, particularly for physical activity, firmly established [43–45], the emphasis has shifted to effectiveness or pragmatic trials designed to answer questions important to informing translation into routine practice (How do we reach the growing number of cancer survivors, many of whom live outside of metropolitan areas? Which health care providers are best suited to deliver lifestyle interventions, and what are the resources required for intervention delivery? Are post-intervention improvements in patient-reported outcomes maintained or are booster sessions needed?) [46–49].

A particular area of interest has been the evaluation of broad-reach or distance intervention modalities, particularly the telephone, as this mode of delivery has the potential for far greater reach compared to face-to-face delivered interventions [32, 34, 35]. A recent systematic review of 27 trials of broad-reach lifestyle interventions among cancer survivors (22 of them telephone-delivered) found evidence for improvements in lifestyle behaviours and weight loss across cancer survivor groups [50]. In a comparative-effectiveness trial of an exercise intervention for women during and after treatment for breast cancer, a telephone-delivered intervention was as effective as a face-to-face-delivered intervention for achieving improvements in fitness and quality of life [51, 52] and suitable for reaching women living in regional and rural Australia [53]. This now large body of evidence on the efficacy and effectiveness of lifestyle interventions among diverse cancer survivors, including evidence for the effectiveness of telephone delivery, sets the stage for the present study and a future mechanism of routine support for cancer survivors.

The Healthy Living after Cancer partnership

Healthy Living after Cancer (HLaC) is a dissemination and implementation study that will evaluate the integration of an evidence-based lifestyle intervention for cancer survivors into an existing telephone cancer information and support service delivered by the Australian state-based Cancer Councils. Outcomes, as described in detail below, are service-level and consumer/patient-reported.

In Australia, the Cancer Councils are non-governmental, not-for-profit, cancer control organisations located in each state and territory that deliver programs and provide information and support across the cancer continuum from cancer prevention through to cancer survivorship. They also fund as well as conduct research. The Cancer Councils offer a telephone “13 11 20 Cancer Information and Support Service” (previously known as the Helpline) with coverage across Australia. This existing service delivery infrastructure, combined with the priority placed on survivorship support, and their position stand on nutrition and physical activity for cancer survivors [9], provide an optimal framework on which to scale-up, implement nationally and evaluate an evidence-based lifestyle intervention for cancer survivors.

The five largest Cancer Councils were approached for collaboration, with four agreeing to take part (Cancer Councils New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia). The Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Partnership Projects scheme, which is designed to support academic-industry research partnerships leading to translation of results into health policy and practice [54], was targeted for funding. A concept development workshop was organised to engage cancer policy and practice stakeholders, including the Cancer Councils, along with national and international lifestyle and cancer survivorship experts and clinicians (co-authors on this paper). The workshop was sponsored by two Australian Cancer Trials Groups, which led to the development of a funding proposal, and the subsequent collaboration that now governs the Healthy Living after Cancer Partnership Project.

The five-year study will be conducted in three phases: Phase 1 involves knowledge transfer and capacity building (Year 1). In this phase, the research team will work closely with Cancer Council partners to facilitate their ability to implement and evaluate HLaC, including database adaptations, staff training and input from Cancer Council staff on program materials. Phase 2 involves HLaC implementation and evaluation (Years 2–5), with intervention procedures and the evaluation plan described below. Phase 3 involves advocacy within the Cancer Councils, alongside communication of HLaC outcomes to the broader cancer control community and health care sector, in an effort to obtain sustained funding for the program (Years 4–5).

Methods/Design

Study design

The HLaC dissemination and implementation study uses a single-group, pre-post-test study design. The research questions to be answered are those important to informing translation into practice, particularly the feasibility and costs associated with wide-scale program implementation [46, 55] and the cancer survivor outcomes that can be achieved in the health services delivery context. Accordingly, the RE-AIM Framework (reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, maintenance) [56] is used to guide systematic evaluation, with assessment of: the reach of the intervention (i.e., the number and representativeness of service referrers and participants/consumers); program implementation (i.e., number of referrals, consent rates, fidelity of delivery, program completion rates and costs to deliver); effectiveness (i.e., cancer survivor outcomes including behavioural, anthropometric and psychosocial variables); and maintenance (i.e., the capacity of the Cancer Councils to continue to deliver the service following the end of this study). Ethical approval was granted from the human research ethics committees of the following institutions: Cancer Council Victoria (on behalf of Cancer Councils Victoria and South Australia), Cancer Council New South Wales, the University of Queensland and the University of Western Australia (on behalf of Cancer Council Western Australia). Ethical approval is also sought as required for referring clinical sites in these states.

Participants and referral pathways

The HLaC program is targeted to any adult cancer survivor who has been treated with curative intent and who has completed treatment. Referral pathways for potentially eligible participants fall under three broad headings: Cancer Council services and programs (e.g., the 13 11 20 information and support service; survivorship support and education programs); Cancer Council networks and partners (e.g., Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia; Breast Cancer Network Australia); and cancer treatment sites (e.g., metropolitan and regional hospitals). Within these categories, each Cancer Council will develop, in conjunction with the research team, its own HLaC referral pathways based on local knowledge and with a study-wide agreed emphasis on outreach to non-urban areas in which 30 % of Australian cancer survivors reside [57].

Cancer Council staff will provide representatives at each referring organisation or site with information about the HLaC program (a referrer information sheet), along with promotional material (posters and brochures), and will be encouraged to recommend the program to any potentially interested and eligible patients and cancer survivors. Based on varying ethics requirements across sites, at some, interested patients will give verbal consent for their name and contact details to be forwarded to their local Cancer Council so that HLaC project staff may telephone them to discuss the program in more depth (including screening for eligibility). At other sites, interested patients will be given a referral form to return to their Cancer Council. Interested cancer survivors may also self-refer by telephoning 13 11 20 and enquiring directly about the program at any time, as advertised on the promotional posters and brochures.

Accrual targets

The overarching aim is for each Cancer Council to deliver the program over a three-year period. This should afford adequate experience with program implementation and familiarity with outcomes to inform decisions on program sustainability. Accrual targets for each Cancer Council are based on available resources to implement the program. There is capacity for each participating Cancer Council to achieve approximately 50–60 program completions/year implementing the HLaC program 6-month/12 call protocol (refer to the program delivery section). With an estimated 30 % attrition, each Cancer Council would therefore need to enrol approximately 75–80 participants per year. The attrition estimate is based on the high (nearly 50 %) attrition observed in other disseminated lifestyle intervention programs in the general adult population [58, 59], but tempered by the fact that cancer survivors tend to be highly motivated such that cancer-specific trials generally achieve 90 % 12-month retention [32, 35, 52, 53, 60]. Across the three years of HLaC implementation, it is anticipated that each Cancer Council will achieve completion rates of approximately 150–180 participants, for a total of approximately 600–680 HLaC completing (from 900 enrolled) during the proposed study (refer to the sample size section).

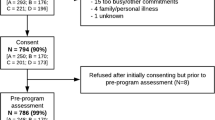

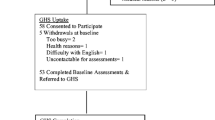

Screening and consent

The eligibility criteria for the HLaC program are designed to be as broad as possible, thereby maximising the diversity of survivors who are able to take part and ensuring participants are able to do so safely. The eligibility criteria are: adults (18+ years); diagnosed with localised (i.e., non-metastatic) cancer of any type treated with curative intent; completed primary treatment (i.e., surgery, chemotherapy, radiation; patients currently receiving hormonal treatment or Herceptin are still eligible); no contraindications to engaging in unsupervised physical activity (i.e., active heart disease, breathing problems requiring hospitalisation in the past 6 months, undergoing dialysis, diabetic complications such as severe neuropathy or retinopathy, planning a knee or hip replacement in the next six months, pregnant); no cognitive or mental health impairments that would hinder program participation; able to speak and read English sufficiently to allow for program participation; wanting support for healthy living via physical activity and healthy eating and willing to make a six-month commitment to HLaC program participation. Screening will occur over the telephone by Cancer Council staff utilising a recruitment and screening script, with eligibility based on patient self-report (Table 1). In cases where eligibility is uncertain, the patient will be asked to seek permission to take part from their treating clinician and report back to Cancer Council staff, with the outcome recorded in the database. Those eligible will be posted an information sheet and a follow-up telephone call will be completed a week later to obtain informed consent (verbal and audiotaped or paper-based, depending upon the recruitment protocol used at the referring site).

Healthy Living after Cancer program

The six-month HLaC program is aimed at increasing physical activity, promoting healthy eating, and assisting with moderate weight loss (if indicated), consistent with current evidence and guidelines for nutrition and physical activity in cancer survivors (Table 2) [8–10]. Delivered by study-trained, Cancer Council nurses/allied health professionals with expertise in cancer care, it will provide the necessary support and advice to meet these guidelines while dealing with common cancer survivorship issues including lymphoedema, pain, fatigue and fear of recurrence. Participants will receive up to 12 telephone calls over the 6-month program along with a HLaC Participant Workbook (Table 3) used to support intervention delivery.

Cancer Council nurses/allied health professionals will be trained in the HLaC protocol by study investigators. A Training Manual detailing the intervention protocol, including example call scripts, will be made available to all trainees prior to a two-day, group-based training workshop, which makes extensive use of role-playing. Using a train-the-trainer approach, the training is video-taped and a lead nurse from each Cancer Council will take responsibility for the initial training of any new staff requiring training during the study period. Within each Cancer Council, those delivering the program will debrief weekly on participant progress with the lead HLaC nurse, alongside email access to the research team for support as needed and monthly case management teleconferences organised with the lead investigator.

Intervention delivery is grounded in Social Cognitive Theory constructs of self-efficacy, social support and outcome expectancies [61] and is guided by techniques of motivational interviewing [62] and health behaviour coaching [63]. The emphasis is on developing participant skills in evidence-based behaviour change strategies – goal setting, self-monitoring, problem solving, identifying social support, stimulus control, positive self-talk and self-reward [64]. The structured protocol for each call includes: assessment of progress; problem-solving; advice/education; and collaborative (“SMART”) goal-setting/goal progression (detailing a behaviourally-specific plan for goal achievement).

Intervention procedures

A semi-structured approach to the order in which intervention targets are addressed is used to guide delivery and works in accordance with the Participant Workbook (see Table 3). Participants are encouraged to begin with a focus on increasing physical activity, as it is often more challenging to achieve than making small changes to dietary intake. However, consistent with the motivational interviewing approach, the intervention is tailored to each participant, with an initial focus on targets in areas that the participant is most motivated and confident to change. The intervention is delivered in three phases, with weekly, fortnightly and then monthly calls, as depicted in Table 4.

Physical activity

The physical activity component of the intervention focuses on identifying enjoyable activities that can be easily incorporated into a participant’s lifestyle (e.g., walking), with gradual increases in physical activity aimed at meeting or exceeding the target of 30 minutes per day of moderate-to-vigorous intensity activity daily. Resistance exercise (2–3 sessions/week) is also encouraged, with detailed photographs and instructions, guidelines on the number of sets and repetitions of each exercise, and options for progression, outlined in the Participant Workbook. In addition to daily planned physical activity, participants are encouraged to capitalise on opportunities to be active in and around their homes and workplaces (e.g., gardening, housework, taking the stairs) [65–67] and to reduce sitting time (i.e., to get up and move every 30 minutes and to aim for no more than 2 hours/day of screen time outside of work) [68–70].

Diet and weight loss

All participants are encouraged to achieve three overarching dietary aims: 1) increasing intake of vegetables, fruit and whole grains; 2) reducing intake of foods high in added sugars and fat (especially saturated fats) and 3) limiting portion size and improving dietary quality. In addition, those who are overweight and want to work towards modest weight loss (i.e., 5–10 % of initial body weight) focus on reducing energy intake by 2,000 kJ per day. Strategies to reduce energy intake include: improving portion control (by reducing portion size or number of serves) and lowering energy density (by increasing intake of low energy dense foods such as fruits and vegetables and reducing intake of foods with high energy density such as high fat/sugar foods).

Data collection

All study data are collected by study-trained Cancer Council staff as this enables capacity building for ongoing program evaluation. Study funding is used to ensure that each Cancer Council has a dedicated research assistant to support evaluation. Study protocol implementation and data quality control are monitored via weekly database reports submitted by Cancer Council staff to the research team.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Outcomes are shown in Table 5, along with the relevant RE-AIM indicators and measurement tools. Primary (service-level) outcomes include referrals, call delivery, completion rates, participant and staff satisfaction and program delivery costs, and will be systematically collected in each of the Cancer Council databases. Secondary (anthropometric, behavioural and psychosocial) outcomes are patient-reported during pre- and post-program assessments conducted by Cancer Council staff via telephone and using validated protocols and questionnaires.

Statistical analyses

Primary outcomes for HLaC implementation will be reported descriptively. Analyses of secondary (effectiveness) outcomes will be by mixed models, which allow for repeated measures (baseline and follow-up) and will include all participants with baseline data (including those with missing data at follow-up) with adjustment for predictors of dropouts to minimise non-response bias. Data will be analysed collectively (pooled) across Cancer Councils as well as reported individually for each. To minimise type I errors because of testing multiple outcomes, significance will be set at p < 0.001 (two-tailed). Sensitivity of conclusions to missing data assumptions will be evaluated.

Sample size related to secondary (effectiveness) outcomes

Given the resources available in each Cancer Council to support HLaC implementation, the service delivery is expected to provide a sample size of approximately 900 participants across the four participating Cancer Councils over the three year recruitment period. This sample provides >90 % power with two-tailed significance of p < 0.001 to detect pre-post changes of 60 minutes of physical activity per week, 0.5 serves of fruit or vegetables, 2 kg weight and clinically relevant changes in physical and mental components of quality of life (3 units each) [71], based on assumed standard deviations of change of 300 min/week, 1.5 fruit and 2 vegetable serves, 8 kg weight, and 8 units on the mental and physical component scores. These calculations allow for 30 % participant attrition and adjustment for up to 10 covariates (10 observations per covariate).

Economic appraisal

The economic questions associated with this research relate to the costs of implementing HLaC and the relationship between costs, program completion and outcomes. Specifically:

-

Costs of implementing HLaC: The fixed costs (i.e., expenditure required to deliver the HLaC program, including resources associated with modifying Cancer Council databases, refining referral pathways, adapting the intervention and evaluation protocols and recruiting and training nurses) will be documented. Dollar values will be attached to these resources using publicly available information such as appropriate salary rates for the time of personnel involved in the above activities and commercial prices for the production of any training materials, etc. Fixed costs will be allocated equally over all participants who consent to participate in HLaC. Variable costs (i.e., those that are proportional to the volume of service provided) will be allocated in proportion to the stage of HLaC reached by individuals [72].

-

Relationship between costs, completion and outcomes: Stage of completion will be defined as follows: Stage 1 = completion of ≥3 x weekly phone calls; Stage 2 = completion of Stage 1 + ≥3 x fortnightly phone calls; Stage 3 = completion of stages 1 + 2 + ≥3 monthly calls. For the purposes of the economic appraisal, outcomes will be defined using a series of pre-defined benchmarks based on pre-post program changes in the behavioural and anthropometric variables. For total physical activity, participants who reported achieving 150 minutes/week are considered as having made improvements in their physical activity level. For vegetables and fruit, participants who reported achieving the target of 5 and 2 serves/day, respectively, are classified as having made positive changes in their dietary behaviour. For weight (among participants where weight loss is indicated), those who recorded a body weight reduction at follow-up ≥3 % of their baseline weight will be classified as having successfully achieved a health enhancing benefit [73]. Regression analysis will be used to assess the relationship between completion of stages and outcomes achieved. It is hypothesised that those who complete Stage 3 will have better outcomes than Stage 2 completers who in turn will have better outcomes than those who do not proceed beyond Stage 1. Pre- and post-test differences will be calculated as changes in Quality of Life (SF-12) and Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) SF6D [74] (calculated from SF-12). Data will be analysed with and without imputed outcomes. Sensitivity analysis will be used to explore the impact of varying assumptions about the cut-offs used to define improvements in the secondary outcomes noted above.

Discussion

This study represents the first scaled-up and national-level implementation and evaluation of an evidence-based lifestyle intervention for cancer survivors in collaboration with a peak cancer control and community facing partner. As such, it is consistent with calls for the conduct of practice-based and dissemination research that accelerates the transfer of cancer survivorship research into evidence-based cancer care [47–49]. A participatory and collaborative approach has been used to build both capacity amongst Cancer Councils for program delivery and evaluation and to ensure the collection of outcomes data necessary to inform decisions about sustained funding. Accordingly, from the outset, the study has engaged a group of cancer policy, practice and service delivery stakeholders, along with lifestyle and cancer survivorship experts and cancer clinicians. This transdisciplinary collaboration provided guidance on study design, evaluation and intervention protocol adaptation and will oversee study implementation, culminating in consideration of and advocacy around study findings in relation to sustained funding for HLaC program delivery.

As a dissemination and implementation study there are some inherent limitations. The use of a single group, pre-post study design is primary among these. However, the primary questions to be answered are about the feasibility and costs of wide-scale implementation, and the survivor outcomes that can be achieved in this context. Numerous previous efficacy trials have answered the question as to whether lifestyle intervention is superior to usual care or no intervention [43–45, 75–77]. The use of self-report measures of health behaviour changes is a limitation [78, 79], however, all self-reported tools have been validated, including against objective measurement where feasible [80–82], and have been used in cancer samples, with the national scale of implementation and resource limitations precluding collection of clinically-assessed outcomes. The collection of data by Cancer Council staff, some of whom will have a role in program delivery, may be a source of bias. However, in this context, it was felt that (i) the emphasis on building evaluation capacity among the Cancer Council partners outweighed any inherent bias and (ii) this protocol is more closely representative of the real-world process of program delivery and evaluation, with both important for supporting the final phase of the project, specifically, advocating for sustained HLaC delivery beyond the funding period.

It is important to note that the healthy living targets being promoted in this study, and ratified by Cancer Council Australia and the World Cancer Research Fund, are based on general population recommendations for cancer prevention [8–10]. And further, that the vast majority of lifestyle intervention evidence among cancer survivors has been conducted in healthier samples with early (not advanced) cancers. Accordingly, the HLaC study targets survivors treated with curative intent. There is still more research needed to inform the safety, feasibility and efficacy of lifestyle interventions for those with advanced cancers, as well as understanding the upper and lower thresholds for physical activity, dietary change, and weight loss, and the optimal sequencing of these multiple lifestyle intervention targets.

The HLaC study is national in scope, involving the relevant cancer control stakeholders and multidisciplinary expertise; is based on broad inclusion of cancer survivors; and includes an evaluation of both service-level indicators and associated costs and cancer survivor outcomes. The evidence to be generated from this collaborative study is what is directly required to influence health policy and practice related to cancer survivorship care around provision of support for healthy living after cancer.

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer survival and prevalence in Australia: Period estimates from 1982 to 2010. Cancer Series no. 69. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2012.

Youlden DR, Cramb SM, Dunn NAM, Muller JM, Pyke CM, Baade PD. The descriptive epidemiology of female breast cancer: An international comparison of screening, incidence, survival and mortality. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;36(3):237–48.

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [database on the Internet]. International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2013. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr. Accessed 26 Aug 2015.

Baade PD, Fritschi L, Eakin EG. Non-cancer mortality among people diagnosed with cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17(3):287–97.

Carver JR, Shapiro CL, Ng A, Jacobs L, Schwartz C, Virgo KS, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical evidence review on the ongoing care of adult cancer survivors: Cardiac and pulmonary late effects. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(25):3991–4008.

Eakin EG, Youlden DR, Baade PD, Lawler SP, Reeves MM, Heyworth JS, et al. Health status of long-term cancer survivors: Results from an Australian population-based sample. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(10):1969–76.

Travis LB, Demark-Wahnefried W, Allan JM, Wood ME, Ng AK. Aetiology, genetics and prevention of secondary neoplasms in adult cancer survivors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10(5):289–301.

Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Meyerhardt J, Courneya KS, Schwartz AL, et al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(4):243–74.

Cancer Council Australia. Position statement on nutrition and physical activity. Cancer Council Australia, 2013. http://www.cancer.org.au/policy-and-advocacy/position-statements/nutrition-and-physical-activity/. Accessed 26 Aug 2015.

World Cancer Research Fund, American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer: A global perspective. Washington DC: AICR2007. http://www.aicr.org/assets/docs/pdf/reports/Second_Expert_Report.pdf. Accessed 26 Aug 2015.

Blanchard CM, Courneya KS, Stein K, American Cancer Society’s SCS-II. Cancer survivors’ adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: Results from the American Cancer Society’s SCS-II. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(13):2198–204.

Eakin E, Youlden DR, Baade PD, Lawler SP, Reeves MM, Heyworth JS, et al. Health behaviors of cancer survivors: data from an Australian population-based survey. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18:881–94.

Berry N, Miller M, Woodman R, Coveney J, Booth S, Dollman J, et al. Differences in chronic conditions and lifestyle behaviour between people with a history of cancer and matched controls. Med J Aust. 2014;201:96–100.

Courneya KS, Katzmarzyk PT, Bacon E. Physical activity and obesity in Canadian cancer survivors: population-based estimates from the 2005 Canadian Community Health Survey. Cancer. 2008;112(11):2475–82.

Irwin ML, Crumley D, McTiernan A, Bernstein L, Baumgartner R, Gilliland FD, et al. Physical activity levels before and after a diagnosis of breast cancer: The Health, Eating, Activity, and Lifestyle (HEAL) study. Cancer. 2003;97(7):1746–57.

Vagenas D, DiSipio T, Battistutta D, Demark-Wahnefried W, Rye S, Bashford J, et al. Weight and weight change following breast cancer: Evidence from a prospective, population-based, breast cancer cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2015;15(28). doi:10.1186/s12885-015-1026-2.

Demark-Wahnefried W, Peterson B, McBride C, Lipkus I, Clipp E. Current health behaviors and readiness to pursue life-style changes among men and women diagnosed with early stage prostate and breast carcinomas. Cancer. 2000;88(3):674–84.

James EL, Eakin E, Girgis A, Reeves M, Paras L, Boyes A, et al. What are cancer survivors’ priorities and preferences for lifestyle programs? Paper presented at the Clinical Oncological Society of Australia and the International Association of Cancer Registries Joint Scientific Meeting, held in conjunction with the Australian and New Zealand Gastro-Oesophageal Surgery Association; 18-20 November 2008; Sydney, Australia. Asia-Pac J Clin Oncol. 2008;4(S2):A76.

Christian A, Hudson SV, Miller SM, Bator A, Ohman-Strickland PA, Somer RA, et al. Perceptions of primary care among breast cancer survivors: The effects of weight status. Health Serv Res Manag Epidemiol. 2015;2:1–8.

Courneya KS, Segal RJ, Mackey JR, Gelmon K, Reid RD, Friedenreich CM, et al. Effects of aerobic and resistance exercise in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(28):4396–404.

Courneya KS, Sellar CM, Stevinson C, McNeely ML, Peddle CJ, Friedenreich CM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of aerobic exercise on physical functioning and quality of life in lymphoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(27):4605–12.

Demark-Wahnefried W, Kenyon AJ, Eberle P, Skye A, Kraus WE. Preventing sarcopenic obesity among breast cancer patients who receive adjuvant chemotherapy: Results of a feasibility study. Clin Exerc Physiol. 2002;4(1):44–9.

Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Hannan PJ, Yee D. Safety and efficacy of weight training in recent breast cancer survivors to alter body composition, insulin, and insulin-like growth factor axis proteins. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(7):1672–80.

Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Troxel A, Cheville A, Smith R, Lewis-Grant L, et al. Weight lifting in women with breast-cancer-related lymphedema. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(7):664–73.

Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Troxel AB, Cheville A, Lewis-Grant L, Smith R, et al. Weight lifting for women at risk for breast cancer-related lymphedema: A randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304(24):2699–705.

Vardy JL, Bell M, van der Ploeg H, Turner J, Kabourakis M, Spencer L, et al. The impact of physical activity on fatigue and quality of life in lung cancer patients: A randomised controlled trial (RCT). J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(15 Suppl):9507.

Lynch BM, Courneya KS, Sethi P, Patrao TA, Hawkes AL. A randomized controlled trial of a multiple health behavior change intervention delivered to colorectal cancer survivors: Effects on sedentary behavior. Cancer. 2014;120(17):2665–72.

Courneya KS, Vardy J, Gill S, Jonker D, O’Brien P, Vardy J, et al. Update on the Colon Health and Life-Long Exercise Change Trial: A phase III study of the impact of an exercise program on disease-free survival in colon cancer survivors. Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep. 2014;10:321–8.

Hawkes AL, Chambers SK, Pakenham KI, Patrao TA, Baade PD, Lynch BM, et al. Effects of a telephone-delivered multiple health behavior change intervention (CanChange) on health and behavioral outcomes in survivors of colorectal cancer: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(18):2313–21.

von Gruenigen V, Frasure H, Kavanagh MB, Janata J, Waggoner S, Rose P, et al. Survivors of uterine cancer empowered by exercise and healthy diet (SUCCEED): a randomized controlled trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125(3):699–704.

Dhillon HM, van der Ploeg HP, Bell ML, Boyer M, Clarke S, Vardy J. The impact of physical activity on fatigue and quality of life in lung cancer patients: A randomised controlled trial protocol. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:572.

Demark-Wahnefried W, Morey MC, Sloane R, Snyder DC, Miller PE, Hartman TJ, et al. Reach out to enhance wellness home-based diet-exercise intervention promotes reproducible and sustainable long-term improvements in health behaviors, body weight, and physical functioning in older, overweight/obese cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(19):2354–61.

Ottenbacher AJ, Day RS, Taylor WC, Sharma SV, Sloane R, Snyder DC, et al. Long-term physical activity outcomes of home-based lifestyle interventions among breast and prostate cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(10):2483–9.

Morey MC, Snyder DC, Sloane R, Cohen HJ, Peterson B, Hartman TJ, et al. Effects of home-based diet and exercise on functional outcomes among older, overweight long-term cancer survivors: RENEW: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(18):1883–91.

Demark-Wahnefried W, Clipp EC, Lipkus IM, Lobach D, Clutter Snyder D, Sloane R, et al. Main outcomes of the FRESH START trial: A sequentially tailored, diet and exercise mailed print intervention among breast and prostate cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(19):2709–18.

McCarroll ML, Armbruster S, Pohle-Krauza RJ, Lyzen AM, Min S, Nash DW, et al. Feasibility of a lifestyle intervention for overweight/obese endometrial and breast cancer survivors using an interactive mobile application. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(3):508–15.

Grimmett C, Simon A, Lawson V, Wardle J. Diet and physical activity intervention in colorectal cancer survivors: A feasibility study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19(1):1–6.

O’Neill RF, Haseen F, Murray LJ, O’Sullivan JM, Cantwell MM. A randomised controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of a 6-month dietary and physical activity intervention for patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(3):4321–40.

McCarroll ML, Armbruster S, Frasure HE, Gothard MD, Gil KM, Kavanagh MB, et al. Self-efficacy, quality of life, and weight loss in overweight/obese endometrial cancer survivors (SUCCEED): a randomized controlled trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132(2):397–402.

Bantum EO, Albright CL, White KK, Berenberg JL, Lavi G, Ritter PL, et al. Surviving and thriving with cancer using a web-based health behavior change intervention: Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(2):e54.

Ligibel JA, Meyerhardt J, Pierce JP, Najita J, Shockro L, Campbell N, et al. Impact of a telephone-based physical activity intervention upon exercise behaviors and fitness in cancer survivors enrolled in a cooperative group setting. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132(1):205–13.

James EL, Stacey F, Chapman K, Lubans DR, Asprey G, Sundquist K, et al. Exercise and nutrition routine improving cancer health (ENRICH): The protocol for a randomized efficacy trial of a nutrition and physical activity program for adult cancer survivors and carers. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:236.

Fong DY, Ho JW, Hui BP, Lee AM, Macfarlane DJ, Leung SS, et al. Physical activity for cancer survivors: Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br Med J. 2012;344:e70.

Schmitz KH, Holtzman J, Courneya KS, Masse LC, Duval S, Kane R. Controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(7):1588–95.

Speck RM, Courneya KS, Mâsse LC, Duval S, Schmitz KH. An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4(2):87–100.

Milat AJ, Bauman AE, Redman S, Curac N. Public health research outputs from efficacy to dissemination: a bibliometric analysis. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:934.

Phillips SM, Alfano CM, Perna FM, Glasgow RE. Accelerating translation of physical activity and cancer survivorship research into practice: Recommendations for a more integrated and collaborative approach. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(5):687–99.

Alfano CM, Smith T, de Moor JS, Glasgow RE, Khoury MJ, Hawkins NA, et al. An action plan for translating cancer survivorship research into care. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(11): doi:10.1093/jnci/dju287.

Ligibel JA, Alfano CM, Courneya KS, Demark-Wahnefried W, Burger RA, Chlebowski RT, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology position statement on obesity and cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(31):3568–74.

Goode AD, Lawler SP, Brakenridge CL, Reeves MM, Eakin EG. Telephone, print, and Web-based interventions for physical activity, diet, and weight control among cancer survivors: A systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2015; [Epub ahead of print].

Hayes S, Rye S, Battistutta D, Yates P, Pyke C, Bashford J, et al. Design and implementation of the Exercise for Health trial - A pragmatic exercise intervention for women with breast cancer. Contemp Clin Trials. 2011;32(4):577–85.

Hayes SC, Rye S, Disipio T, Yates P, Bashford J, Pyke C, et al. Exercise for health: a randomized, controlled trial evaluating the impact of a pragmatic, translational exercise intervention on the quality of life, function and treatment-related side effects following breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137(1):175–86.

Eakin EG, Lawler SP, Winkler EA, Hayes SC. A randomized trial of a telephone-delivered exercise intervention for non-urban dwelling women newly diagnosed with breast cancer: Exercise for Health. Ann Behav Med. 2012;43(2):229–38.

National Health and Medical Research Council. NHMRC Partnerships for Better Health. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/grants-funding/apply-funding/partnerships-better-health. Accessed 26 Aug 2015.

Glasgow RE, Emmons KM. How can we increase translation of research into practice? Types of evidence needed. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:413–33.

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM Framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1322–7.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Rural, regional and remote health: A guide to remoteness classifications. Catalogue Number PHE 532004. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2004.

Goode AD, Reeves M, Owen N, Eakin E. Results from the dissemination of an evidence-based telephone-delivered intervention for healthy lifestyle and weight loss: The Optimal Health Program. Transl Behav Med. 2013;3(4):340–50.

O’Hara BJ, Phongsavan P, Venugopal K, Eakin EG, Eggins D, Caterson H, et al. Effectiveness of Australia’s Get Healthy Information and Coaching Service®: Translational research with population wide impact. Prev Med. 2012;55(4):292–8.

Demark-Wahnefried W, Clipp EC, Morey MC, Pieper CF, Sloane R, Snyder DC, et al. Lifestyle intervention development study to improve physical function in older adults with cancer: outcomes from Project LEAD. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(21):3465–73.

Emmons KM, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing in health care settings. Opportunities and limitations. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(1):68–74.

Eakin EG, Reeves MM, Marshall AL, Dunstan DW, Graves N, Healy GN, et al. Living Well with Diabetes: a randomized controlled trial of a telephone-delivered intervention for maintenance of weight loss, physical activity and glycaemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:452.

Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143–64.

Michie S, Abraham C, Whittington C, McAteer J, Gupta S. Effective techniques in healthy eating and physical activity interventions: a meta-regression. Health Psychol. 2009;28(6):690–701.

Healy GN, Dunstan DW, Salmon J, Cerin E, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ, et al. Objectively measured light-intensity physical activity is independently associated with 2-h plasma glucose. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1384–9.

Hu FB, Li TY, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Manson JE. Television watching and other sedentary behaviors in relation to risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. JAMA. 2003;289(14):1785–91.

Lahmann PH, Friedenreich C, Schuit AJ, Salvini S, Allen NE, Key TJ, et al. Physical activity and breast cancer risk: the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(1):36–42.

Dunstan DW, Barr EL, Healy GN, Salmon J, Shaw JE, Balkau B, et al. Television viewing time and mortality: the Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab). Circulation. 2010;121(3):384–91.

Thorp AA, Healy GN, Owen N, Salmon J, Ball K, Shaw JE, et al. Deleterious associations of sitting time and television viewing time with cardiometabolic risk biomarkers: Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle (AusDiab) study 2004-2005. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(2):327–34.

Australian Government Department of Health. Australia’s physical activity and sedentary behaviour guidelines for adults (18-64 years). Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health; 2014.

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Bjorner JB, Turner-Bowker DM, Gandek B, Maruish ME. User’s manual for the SF-36v2 Health Survey. 2nd ed. Lincoln: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2007.

Drummond MF, McGuire A. Economic evaluation in health care: Merging theory with practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001.

National Health and Medical Research Council. Overweight and obesity in adults: A guide for general practitioners. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council; 2003.

Brazier J, Deverill M, Green C, Harper R, Booth A. A review of the use of health status measures in economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 1999;3(9):i–v. 1-164.

Pekmezi DW, Demark-Wahnefried W. Updated evidence in support of diet and exercise interventions in cancer survivors. Acta Oncol. 2011;50(2):167–78.

Reeves MM, Terranova CO, Eakin EG, Demark-Wahnefried W. Weight loss intervention trials in women with breast cancer: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2014;15(9):749–68.

Spark LC, Reeves MM, Fjeldsoe BS, Eakin EG. Physical activity and/or dietary interventions in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review of the maintenance of outcomes. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(1):74–82.

Macdiarmid J, Blundell J. Assessing dietary intake: Who, what and why of under-reporting. Nutr Res Rev. 1998;11:231–53.

Prince SM, Adamo KB, Hamel ME, Hardt J, Connor Gorber S, Tremblay M. A comparison of direct versus self-report measures for assessing physical activity in adults: A systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5:56.

Lassale C, Peneau S, Touvier M, Julia C, Galan P, Hercberg S, et al. Validity of web-based self-reported weight and height: Results of the Nutrinet-Sante Study. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(8):e152.

Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Chute CG, Litin LB, Willett WC. Validity of self-reported waist and hip circumferences in men and women. Epidemiology. 1990;1(6):466–73.

Brown WJ, Burton NW, Marshall AL, Miller YD. Reliability and validity of a modified self-administered version of the Active Australia physical activity survey in a sample of mid-age women. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2008;32(6):535–41.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The Active Australia Survey: A guide and manual for implementation, analysis and reporting. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2003.

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381–95.

Reeves MM, Winkler EAH, Eakin EG. Fat and Fibre Behaviour Questionnaire: Reliability, relative validity and responsiveness to change in Australian adults with type 2 diabetes and/or hypertension. Nutr Diet. 2014. doi:10.1111/1747-0080.12160.

Rutishauser IHE, Webb K, Abraham B, Allsopp R. Evaluation of short dietary questions from the 1995 National Nutrition Survey. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2001.

Sanderson K, Andrews G. The SF-12 in the Australian population: Cross-validation of item selection. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2002;26(4):343–5.

Cleeland CS. The M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory, User Guide, Version 1.0, 2009. http://www.mdanderson.org/education-and-research/departments-programs-and-labs/departments-and-divisions/symptom-research/symptom-assessment-tools/MDASI_userguide.pdf. Accessed 26 Aug 2015

Thewes B, Zachariae R, Christensen S, Nielsen T, Butow P. The Concerns about Recurrence Questionnaire: Validation of a brief measure of fear of cancer recurrence amongst Danish and Australian breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2014. doi:10.1007/s11764-014-0383-1.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Distress Thermometer for Patients. http://www.nccn.org/patients/resources/life_with_cancer/pdf/nccn_distress_thermometer.pdf. Accessed 26 Aug 2015.

Akizuki N, Yamawaki S, Akechi T, Nakano T, Uchitomi Y. Development of an impact thermometer for use in combination with the distress thermometer as a brief screening tool for adjustment disorders and/or major depression in cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29(1):91–9.

Acknowledgements

Healthy Living after Cancer is a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Partnership Project (APP10743456) and is supported by funding from the NHMRC and from Cancer Councils New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia. EGE is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Senior Research Fellowship in Population Health (APP1041789). SCH is supported by a Cancer Council Queensland Fellowship. MMR is supported by a National Breast Cancer Foundation Early Career Fellowship (ECR-13-09). JLV is supported by a National Breast Cancer Foundation Practitioner Fellowship. FB is supported by The Friends of the Mater Foundation. GDM is supported by an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT120100812). KSC is supported by the Canada Research Chairs Program. AG is supported by a Cancer Institute NSW grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

EGE, SCH, MRH, MMR, JLV, FB, JEH, GDM, ADG, MJ, BK, CMS, WD-W, KSC, KHS, AG, KW, KC, AGB, SM and GS are the principal and associate investigators of the project. They were extensively involved in the development of the HLaC concept and design and also provide project governance. KL, LM, LO’B, PB and ELR assist with supervision of the project and provide administrative and technical support. All authors were involved in drafting and critically revising the manuscript and also read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Eakin, E.G., Hayes, S.C., Haas, M.R. et al. Healthy Living after Cancer: a dissemination and implementation study evaluating a telephone-delivered healthy lifestyle program for cancer survivors. BMC Cancer 15, 992 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-2003-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-2003-5