Abstract

Background

Owing to the increase in energy consumption, fossil fuel resources are gradually depleting which has led to the growing environmental concerns; therefore, scientists are being urged to produce sustainable and ecofriendly fuels. Thus, there is a growing interest in the generation of biofuels from renewable energy resources using microbial fermentation.

Main text

Butanol is a promising biofuel that can substitute for gasoline; unfortunately, natural microorganisms pose challenges for the economical production of 1-butanol at an industrial scale. The availability of genetic and molecular tools to engineer existing native pathways or create synthetic pathways have made non-native hosts a good choice for the production of 1-butanol from renewable resources. Non-native hosts have several distinct advantages, including using of cost-efficient feedstock, solvent tolerant and reduction of contamination risk. Therefore, engineering non-native hosts to produce biofuels is a promising approach towards achieving sustainability. This paper reviews the currently employed strategies and synthetic biology approaches used to produce 1-butanol in non-native hosts over the past few years. In addition, current challenges faced in using non-native hosts and the possible solutions that can help improve 1-butanol production are also discussed.

Conclusion

Non-native organisms have the potential to realize commercial production of 1- butanol from renewable resources. Future research should focus on substrate utilization, cofactor imbalance, and promoter selection to boost 1-butanol production in non-native hosts. Moreover, the application of robust genetic engineering approaches is required for metabolic engineering of microorganisms to make them industrially feasible for 1-butanol production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Butanol is one of the most promising alternative biofuels because it shows better performance than ethanol [1]. Compared to ethanol, butanol has superior physical and chemical properties, such as higher energy density (27 MJ/L vs. 19.6 MJ/L), low water miscibility, low flammability, lesser corrosiveness, and closely resembles to modern-day gasoline (Table 1). Further, butanol can be blended with gasoline in any ratio and used directly in automobile engines without structural modification, besides being transported through the existing pipeline infrastructure [2, 3]. Butanol also has several applications in various chemical industries. It is used as an intermediate in the production of perfumes, paints, polymers (butyl acrylate and butyl methacrylate) and plastics [4]. In addition, the combustion of 1 kg of butanol emits less CO2 than that emitted by gasoline; to generate an equivalent amount of energy as that of butanol, a larger amount of ethanol needs to be burned, which results in a higher amount of CO2 emission (Fig. 1a) [5]. The global market for butanol was estimated to be 2.8 million tons annually, which is approximately 5 billion USD [6]. Owing to the advantages of butanol over ethanol, there is an increase in the demand for butanol (Fig. 1b). It is expected that the global demands for butanol and other biofuels will surpass 247 billion USD by 2020 [6, 7].

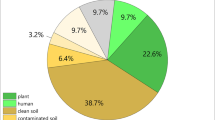

Butanol is produced mostly using petrochemicals (at cost of 7.0–8.4 billion dollars/year) because it is currently cheaper than producing it via biological synthesis [8, 9]. However, the petrochemical synthesis of butanol is very sensitive to crude oil price, which vary considerably (Fig. 1c). Therefore, the petrochemical synthesis of butanol is not a sustainable option that can be continually employed in the near future [10]. Furthermore, the biological production of butanol (biobutanol) is considered as climate neutral. This is because the CO2 released from burning biofuels is approximately equal to the carbon sequestered in biomass [11]. Nowadays, approximately 78.4% of the energy is obtained from fossil fuels (Fig. 1d) [12], and with the depletion of fossil fuel resources and its growing environmental concerns, the production of biobutanol through acetone-butanol-ethanol (ABE) fermentation has gained considerable research attention [9]. However, the production of biobutanol via ABE fermentation still faces significant hurdles, which are discussed below.

The production of 1-butanol by ABE fermentation using Clostridium spp. faces several challenges. First, this process produces other byproducts such as hydrogen, lactic acid and propionic acid, acetone, ethanol, and isopropanol, which increases the downstream processing cost of 1-butanol purification [14]. These native microorganisms also have some limitations such as slow growth, solvent toxicity, complex nutrient requirements, and complicated life cycle (i.e., spore-production in Clostridium) [15, 16]. Furthermore, the genetic manipulation of native producer strains is difficult, and therefore, it is a challenging task to further modify them using different genetic and synthetic biological methods [17]. The current commercial production of 1-butanol through ABE fermentation is based on the fermentation of molasses and starchy materials [18]; the main drawbacks of these fermentation substrates are that the molasses have certain geographical limitations and starchy materials compete with human food. Thus, these natural substrates are not available on a large scale for the production of biofuels [19, 20]. Besides, no solventogenic Clostridium spp. utilizes low-cost feedstock such as cellulose and hemicellulose and other organic wastes (e.g., glycerol) directly; however, an exception is Clostridium pasteurianum that can use glycerol as a substrate [21, 22]. Therefore, non-native hosts are receiving more attention than those native producers for the production of 1-butanol.

In general, non-native hosts have comparatively simple nutrient requirements, rapid growth rate, known genetic background, and they are easy to manipulate, although these conditions can vary on case to case basis. Further, it is economically feasible to use non-native hosts for large-scale production processes [23,24,25]. Recent developments in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering have made it possible to easily create a synthetic pathway for the production of biofuels in the non-native hosts [26]. Thus, in recent years, various non-native hosts that cannot produce 1-butanol in their native forms have been equipped with a 1-butanol production pathway. For example, the pathway has been transferred successfully to Saccharomyces cerevisiae [27] and Escherichia coli [28] owing to their high growth rates. Other microbes such as Lactobacillus brevis, Pseudomonas putida, and Bacillus subtilis were also used for their potentially higher solvent tolerance [29, 30]. Clostridium cellulovorans was engineered because of its ability to consume most effective feedstock (cellulose) as a substrate, while a cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus was used for the direct conversion of CO2 into 1-butanol [31, 32]. Thermophilic bacteria Pyrococcus furiosus and Thermoanaerobacterium saccharolyticum were used for 1-butanol production because of their several distinctive benefits over mesophilic strains. Until now, the most significant advantage of using thermophilic strains is the reduction in contamination risks. All non-native hosts used for 1-butanol production are summarized in Table 2.

The advances and challenges in the engineering of 1-butanol production strains using clostridial species, which are the native 1-butanol producers, have been extensively discussed [8, 16, 33,34,35]. However, a comprehensive review on the engineering of non-native hosts for 1-butanol production is still absent. Engineering of non-native hosts for 1-butanol production faces special challenges owing to their differences from the clostridial species in preference for carbon source, allocation of metabolic flux, generation of cofactors and other physiological features. To guide the rational design of efficient 1-butanol producers, a focused review presenting a full picture for constructing 1-butanol producers using non-clostridial species is highly desired. Here we have summarized the advantageous characteristics of non-native hosts which include, the ability to use cost-efficient feedstock, high solvent tolerance, and less contamination risk. In addition, different engineered synthetic pathways used for 1-butanol production in non-native hosts have been discussed in detail. This paper also elucidates the current challenges faced in 1-butanol production, as well as the possible solutions that can help to improve the production of 1-butanol, and specific areas that need more focus are indicated (Fig. 2). Therefore, we conclude that this study will prove helpful for researchers to overcome the difficulties in engineering non-native hosts for 1-butanol production and to develop efficient means to meet the growing energy requirements of the world.

Advantages of non-native host

Using of alternative carbon sources

Cellulose

The cost of the substrate is one of the most significant factors in ABE fermentation, which constitutes approximately 60% of the total cost of the process [73]. Production of 1-butanol through conventional ABE fermentation is based mainly on starchy materials, which are expensive for the fuel market [74]. On the other hand, cellulosic biomass is present abundantly on the biosphere, is less costly, and does not compete with human food. It is also the substrate of choice for producing bulk products by fermentation. Thus, C. acetobutylicum was engineered to produce 1-butanol using cellulose as carbon source; however, the engineered strain was unable to utilize cellulose because cellulases are complex enzymes that are difficult to be expressed heterologously [75]. Therefore, Instead of expressing cellulases in native 1-butanol producers, a 1-butanol synthetic pathway was transferred into the cellulolytic microbes, i.e. C. cellulovorans and Clostridium cellulolyticum, which efficiently converts it into cost-effective advanced biofuels such as 1-butanol [51, 52].

Glycerol

Glycerol is a by-product of the biodiesel industry, and the production of 20 kg of biodiesel yields approximately 2 kg of crude glycerol [76]. High abundance and low price make glycerol an attractive feedstock to convert it into valuable products [56]. However, the native 1-butanol producers such as C. acetobutylicum, C. beijerinckii, and C. saccharobutylicum are unable to used glycerol as a sole carbon source [77]. On the other hand, C. pasteurianum can utilize glycerol as a carbon source to produce 1-butanol, but due to its complex physiology and limited availability as well as success on the application of genetic tools on it [78], researchers have turned their attention to the non-native producers like E. coli. It grows faster than any Clostridium species and can use glycerol as a carbon source; therefore, it was engineered for 1-butanol production by transferring the CoA-dependent pathway [28]. Additionally, some other heterotrophs such as S. cerevisiae, P. putida, L. brevis, and B. subtilis were also engineered for the production of 1-butanol, using glucose and glycerol as carbon sources. Moreover, another bacterial strain K. pneumonia was engineered for the production of 1-butanol [57], which even grows faster and has a similar genetic background to E. coli and utilizes glycerol as the sole carbon source.

Syngas

Syngas is a mixture of different gases (CO2, CO, and H2). It can be obtained from different sources like coal, biomass, and natural gas, which are also found in some industrial waste gases like in steel industries [79]. From an economic point of view, the production of 1-butanol from syngas is preferred over expensive sources such as sugar-based or starchy materials, which do not compete with food crops and concomitantly help in reducing GHG emissions. Clostridium ljungdahlii and Clostridium autoethanogenum are two acetogenic bacteria that can metabolize such gases via the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway (Fig. 3) [80]. Therefore, C. ljungdahlii and C. autoethanogenum were engineered to produce cost-effective 1-butanol [53, 54]. Hence, 1-butanol production from syngas is considered to be a promising approach towards economic fuel production.

Light and CO2

Sunlight and CO2 are the most easily available and inexpensive energy and carbon sources on earth. Although the proportion of CO2 in the air is low (0 to 0.03%), but the concentration of CO2 in the industrial zone is significantly higher. Sometimes in the industrial zone, the level of CO2 reached 600 to 700 ppm. Moreover, every year, the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere increases by 2–3 ppm because of the burning of fossil fuels [81]. Cyanobacteria is an excellent microbial cell factory that can utilize solar energy and convert atmospheric CO2 to useful products. Additionally, cyanobacteria can grow rapidly, and its genetic manipulation is easy [62]. Owing to its advantages over heterotrophs, cyanobacteria were equipped with a synthetic pathway of 1-butanol, to produce sustainable and eco-friendly biofuels. Recently, a multi-level modular strategy was used to increase the production of 1-butanol in cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803; the engineered strain was able to accumulate the highest titer of 4.8 g/L for 1-butanol with a maximal rate of 302 mg/L/day. It represented the highest 1-butanol titer produced from CO2 in cyanobacteria [63]. Thus, cyanobacteria is a promising strain for the production of the cheapest fuels based on solar energy and more sustainable alternatives to the traditional biofuels.

Resistance to multiple stresses

Solvent tolerant

High-value chemicals and biofuels are toxic to native-hosts and as well as to non-native hosts. The toxicity of the solvent is a significant limiting factor that hinders the production of 1-butanol during the fermentation process. Developing a microbial strain with the ability of a solvent tolerance is a difficult task for the researchers [82]. The current metabolic engineering approaches rely mostly on the deletion or overexpression of some functional genes which are useful to some extent, but it does not necessarily achieve the desired level of tolerance. Stress tolerance is a complex mechanism governed through multilayered networks and cannot be achieved through the deletion or overexpression of a single functional gene [83]. In order to increase the 1-butanol tolerance of the native-hosts, various engineering strategies have been employed. However, native-hosts were unable to tolerate more than 2% of 1-butanol concentration [84, 85]. The researchers have taken an interest in isolating 1-butanol tolerant microbial strains that can act as potential alternative hosts for 1-butanol production. Various microbial strains have been identified, which are amendable by genetic engineering approaches and can tolerate much higher 1-butanol concentrations, including B. subtilis GRSW2-B1, L. brevis (up to 3%), S. cerevisiae YPS128 (up to 4%) and P. putida (up to 6%) [84, 86,87,88]. Therefore, considering the solvent tolerant factor, the synthetic 1-butanol pathway was transferred into L. brevis, P. putida, and B. subtilis, which can grow in the presence of a high amount of 1-butanol [29, 30].

Thermophiles

Thermophilic organisms are a fascinating and promising group of microorganisms due to their several distinct advantages over mesophilic organisms when used as a production host. For example, their ability to thrive in extreme conditions such as high temperature lowers the contamination risk and reduces the production cost due to the elimination of the need for sterilization. Additionally, thermophilic conditions provide the opportunity for continuous removal of volatile compounds [89]. Moreover, co-utilization of hexose or pentose is a highly significant trait of biofuel producing microbes. However, some of the mesophilic strains (e.g., mesophilic Clostridium sp. and Zymomonas mobilis) cannot metabolize two sugars simultaneously due to the mechanism called carbon catabolite repression (CCR) [90, 91]. Interestingly, in many thermophilic organisms, the CCR is absent. In other words, thermophilic organisms (T. saccharolyticum JW/SL-YS485, Thermoanaerobacter sp. X514) can utilize two sugars (pentose and hexose) simultaneously in an unbiased manner for the production of biofuels [92, 93]. Owing to these advantages, thermophilic and hyper-thermophilic microbes (T. saccharolyticum JW/SL-YS485 and P. furiosus) were successfully engineered with the synthetic pathway of 1-butanol [58, 59].

Engineering of non-native hosts for 1-butanol production

Engineering of CoA-dependent pathway

The clostridial CoA-dependent 1-butanol pathway has been heterologously expressed to produce 1-butanol (Fig. 3). The clostridial 1-butanol pathway begins with the condensation of two molecules of acetyl-CoA to synthesize acetoacetyl-CoA catalyzed by thiolase (thl). Acetoacetyl-CoA then undergoes a series of dehydration and reduction to form butyryl-CoA. The genes involved in these enzymatic steps are hbd, crt and bcd-etf complex. The final step of clostridial 1-butanol pathway from butyryl-CoA to 1-butanol, is catalyzed by a bifunctional aldehyde/alcohol dehydrogenase, encoded by either adhE1 or adhE2.

Several efforts have been made to develop the heterologous expression of the CoA-dependent 1-butanol pathway in different non-native hosts. However, initial efforts in heterologous expression of the CoA-dependent pathway resulted in the production of a very minute quantity of 1-butanol [28, 31, 53, 60, 64]. One major problem was the bcd-etf complex enzyme, which expressed poorly in non-native hosts, and this enzyme is also oxygen-sensitive. Second, the initial step of acetyl-CoA condensation is thermodynamically unfavorable. To avoid these problems, alternative enzymes were employed [37, 60, 94]. Solvent tolerant microorganisms, L. brevis, P. putida, and B. subtilis were also engineered for 1-butanol production; however, the engineered strains accumulated lower titers of 1-butanol [29, 30]. A butyric acid producing bacterium, C. tyrobutyricum was engineered to produce 1.1 g/L of 1-butanol by the overexpression of adhE2 gene (Fig. 3), the titers were 3.6-folds, 9-folds and 45-folds higher than the engineered strains of L. brevis, P. putida, and B. subtilis, respectively [44].

Moreover, in order to produce economical 1-butanol, cellulolytic bacteria C. cellulovorans and C. cellulolyticum were engineered for 1-butanol production. Overexpression of adhE2 in C. cellulovorans resulted in the production of 1-butanol at titers up to 1.42 g/L from cellulose, and 3.37 g/L from pretreated corncob, respectively [32, 50]. Expression of the CoA-dependent pathway led to 1-butanol titers up to 0.12 g/L in C. cellulolyticum [52]. To reduce the risk of contamination, the clostridial CoA-dependent pathway was expressed in thermophilic bacteria P. furiosus and T. saccharolyticum JW/SL-YS485, these engineered strains accumulated 70 mg/L and 1.05 g/L of 1-butanol, respectively [58, 59]. Non-pathogenic and non-conventional Blastobotrys adeninivorans haploid yeast was engineered recently, the engineered strain achieved a 1-butanol titer of 20 g/L [72].

The clostridial CoA-dependent pathway was successfully expressed in non-native hosts. However, owing to some limitations of clostridial CoA-dependent pathway such as oxygen-sensitive enzymes, thermodynamically unfavorable steps, and high requirement of reducing power, researchers have explored some alternative 1-butanol synthetic pathways such as Ehrlich pathway, 2-oxoglutarate pathway, and ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway.

Expression of the Ehrlich pathway for 1-butanol production

1-butanol can also be synthesized via the Ehrlich pathway from 2-ketovalerate (ketoacid) using two reaction steps, by the successive action of a 2-ketoacid decarboxylase (kivd) and an alcohol dehydrogenase (adh). 2-ketovalerate can be produced from 2-ketobuturate by ketoacid chain elongation process catalyzed by the endogenous enzymes (LeuABCD), overexpression of the endogenous enzymes can enhance 1-butanol production. 2-ketobutyrate is an intermediate of amino acid biosynthesis pathway that can be produced via native threonine biosynthetic pathway or the heterologous citramalate pathway (Fig. 4).

Taking advantage of utilizing the amino acid biosynthesis pathway intermediates, the Ehrlich pathway was introduced into E. coli for the production of 1-butanol by the expression of heterologous decarboxylase and dehydrogenase [95]. In another study, the citramalate pathway was coupled with the Ehrlich pathway for the production of 1-butanol; the engineered strain produced 0.524 g/L of 1-butanol from glucose [96].

In another study, a novel pathway was created in S. cerevisiae by expressing the glycine oxidase (goxB) gene from B. subtilis, to produce 1-butanol (92 mg/L) using glycine as the substrate via Ehrlich pathway (Fig. 4) [68]. In another approach, an endogenous threonine metabolic pathway was engineered to produce 1-butanol. The overexpression of the endogenous gene related to threonine catabolism and the elimination of other genes affecting the 1-butanol pathway flux generated an engineered strain that produced the highest 1-butanol titer of 242.8 mg/L [69]. Furthermore, to improve the yield of 1-butanol in S. cerevisiae, a synergistic approach was applied using the optimization of the endogenous threonine pathway and the expression of the citramalate synthase (CimA) mediated pathway (Fig. 4). The combination of these metabolic engineering pathways with the co-expression of a related gene improved 1-butanol production to 835 mg/L in the final engineered strain under anaerobic conditions, which is almost a sevenfold increase compared to the initial strain [70].

In briefly, 1-butanol has been synthesized successfully using three different routes via the Ehrlich pathway. However, the major bottleneck in this pathway is the production of non-specific alcohol like 1-propanol because of the broad specificity of kivd gene. Therefore, to effectively produce 1-butanol via the Ehrlich pathway, significant protein engineering, as well as metabolic engineering efforts, are still required.

Engineering of ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway

A facultative methylotrophic α-proteobacterium Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 can use one-carbon as well as multiple carbon compounds as carbon and energy sources. The M. extorquens AM1 is a useful strain in biotechnology as it can produce single-cell proteins, amino acids, poly-β-hydroxybutyrate, and dicarboxylic acids using single carbon compounds [97,98,99]. It has been shown that during the growth of M. extorquens AM1 either using C1 compounds or C2 compounds, a significant metabolic flux occurs through the ethylmalonyl-CoA (EMC) pathway; the EMC pathway is a central metabolic pathway in M. extorquens AM1 that converts acetyl-CoA to glyoxylate for reincorporation into the serine cycle during C1 assimilation and replenishes metabolites that either leave the cycle for biosynthetic purposes or are consumed by the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle during C2 assimilation. The EMC pathway provides a continuous supply of crotonyl-CoA, which can be used as a direct precursor for 1-butanol production [100, 101]. Therefore, the native EMC pathway was engineered in M. extorquens AM1 for 1-butanol production. Carbon flux was directed from its native EMC pathway towards the 1-butanol pathway by expressing the trans-enoyl-CoA reductase gene from T. denticola and the alcohol dehydrogenase gene from C. acetobutylicum (Fig. 3). The recombinant strain produced the highest titer of 8.94 mg/L using ethylamine as a substrate. The titer was increased 1.7-fold (15.2 mg/L) by overexpressing the native crotonase [55]. In another study, adaptive laboratory evolution method was used to isolate a 1-butanol tolerant mutant strain (BHBT5 strain) of M. extorquens AM1. The adaptive mutant strain BHBT5 produced 1.87-fold (25.5 mg/L) more 1-butanol than the base strain BHB9 after introduction of a plasmid harboring the 1-butanol synthetic pathway [102].

2-oxoglutarate pathway for 1-butanol production

In the 2-oxoglutarate pathway, seven enzymatic steps are involved in producing 1-butanol. The resulting set of genes catalyzing seven enzymatic steps are derived from diverse microorganisms. The 2-oxoglutarate pathway uses 2-oxoglutarate intermediate of TCA (try-carboxylic acid) cycle as a starting substrate for 1-butanol production. In the 2-oxoglutarate pathway, first 2-oxoglutarate is converted into 2-hydroxyglutarate by 2-oxoglutarate reductase. In the second reaction, the CoA is transferred from acetyl-CoA to 2-hydroxyglutarate to make 2-hydroxyglutaryl-CoA; this reaction is catalyzed by glutaconate-CoA transferase. In the third reaction, 2-hydroxyglutaryl-CoA is dehydrated into glutaconyl-CoA; this enzymatic step is catalyzed by 2-hydroxyglutaryl-CoA dehydratase. In the fourth reaction, glutaconyl-CoA is decarboxylated into crotonyl-CoA by glutaconyl-CoA decarboxylase. The remaining steps are similar to clostridial pathway. The crotonyl-CoA is reduced to butyryl-CoA by butyryl-CoA dehydrogenase. Finally, the last two steps are successive reductions of butyryl-CoA to butanal and butanal to 1-butanol; the reactions are catalyzed by aldehyde dehydrogenase and alcohol dehydrogenase, respectively [103]. The novel 2-oxoglutarate pathway was introduced into E. coli K12, the engineered strain accumulated the highest 1-butanol titer of 85 mg/L by cultivating the cells in bioreactors using glucose as substrate [103]. The titers of 1-butanol obtained through this pathway are still far below from those required for industrial purposes.

Elimination of the competitive pathways

The strategy of elimination of the competitive pathways has been employed in different non-native hosts, which has successfully increased the titers of 1-butanol by securing the key precursor (like acetyl-CoA) and reducing factor used for 1-butanol synthesis. For example, to increase the flux towards 1-butanol production in E. coli, alternative carbon consuming pathways were deleted by the deletion of the adhE, ldhA and frdBC genes, which shifted the carbon flux towards 1-butanol and resulted in twofold increase in 1-butanol production [28]. In another study, the butyrate-conversion strain (BUT-3EA) of E. coli was engineered by deleting ldhA, adhE, frdA, and pta genes and inserting native atoDA, acs and Clostridium adhE2 genes. The recombinant strain (BuT-3EA) was able to accumulate a titer of 6.2 g/L of 1-butanol using glucose and butyrate as a carbon sources [39], the titers were 1.5-fold higher than the previously engineered strain using glycerol and butyrate as carbon sources [104].

Similarly, Yu et al. deleted ack (encoding acetate kinase) in C. tyrobutyricum to reduce the acetyl-CoA conversion to acetate. The deletion of ack led to a ninefold increase in the titer of 1-butanol [44]. In another study, different replicons from various microorganisms were evaluated to overexpress the C. acetobutylicum adhE2 gene in C. tyrobutyricum. The recombinant strain (without any gene deletion) was able to produce the highest titers of 6.8 g/L and 20.5 g/L of 1-butanol, using glucose and mannitol as the carbon sources, respectively; while the ACKKO-adhE2 mutant (∆ack-adhE2) accumulated 16.68 g/L of 1-butanol (2.5-fold increase) using glucose as the carbon source [46, 47]. Recently, Zhang et al. successfully replaced the cat1 (butyrate: acetate coenzyme A transferase) with adhE2, the mutant Δcat1::adhE2 strain produced 26.2 g/L 1-butanol in batch fermentation. This is the highest 1-butanol production that has ever been reported in batch fermentation [45].

Sakuragi et al. deleted GPD1 and GPD2 (encoding glycerol- 3-phosphate dehydrogenases) genes in S. cerevisiae that compete with 1-butanol production by utilizing the same intermediate metabolites, the deletion of the GPD1 and GPD2 genes resulted in approximately 1.3-fold increase in 1-butanol production [66]. Additionally, the combined deletion of the ADH1, ADH4, GPD1, and GPD2 genes involved in ethanol and glycerol biosynthesis in S. cerevisiae, redirected the carbon flux towards acetyl-CoA, resulting in a fourfold increase in 1-butanol production [67]. Moreover, deletion of CIT2 (encoding citrate synthase) and overexpression of aldehyde dehydrogenase (Ald6), alcohol dehydrogenase (Adh2), and acetyl-CoA synthetase mutant (AcsL641P) to enhance the carbon flux towards cytosolic acetyl-CoA, also led to a 2.5-fold increase in 1-butanol titer [65].

Engineering of rate-limiting steps in 1-butanol production

Metabolomics is a comprehensive study of metabolites in a biological sample. In metabolic engineering, a metabolomics approach is an excellent strategy to search for the rate-limiting step in a biosynthetic pathway. Using metabolomics strategy, Noguchi et al. revealed that the reduction reaction of butanoyl-CoA to butanal catalyzed by acylating aldehyde dehydrogenase (PduP) is a possible rate-limiting step in the 1-butanol pathway in Synechococcus elongatus [105]. Therefore, by enhancing the activity of PduP and inserting the gene encoding the subunit of the ACCase from Yarrowia lipolytica into the aldA (encodes for alcohol dehydrogenase) site, S. elongatus recombinant strain DC11 was able to accumulate 418.7 mg/L of 1-butanol, which is almost 1.4-fold more than its parent strain BUOHSE after 6 days of fermentation [62].

Similarly, Ohtake et al. also used a metabolomics approach to determine the bottleneck in the engineered pathway of 1-butanol. They discovered that the deletion of the pta gene (encoding phosphate acetyltransferase) resulted in pathway imbalance as it prevents the release of CoA; they identified the adhE2-mediated reaction (conversion of butyryl-CoA to butyryl-dehyde) as the rate-limiting step. Thus, a simultaneous balancing of the CoA and enhancing the activity of adhE2 increased the titer of 1-butanol up to 1.3-fold (E. coli JCL299FT strain) compared with its parent strain JCL299F under anaerobic conditions [42]. These results indicate that engineering the rate-limiting step has a significant effect in improving the production of 1-butanol.

Comparison of the different pathways of 1-butanol

Different synthetic pathways aforementioned were used for the production of 1-butanol. In these engineered pathways, clostridial CoA-dependent 1-butanol pathway is one of the most well-known pathway used for 1-butanol production in the heterologous hosts. One of the major advantages could be that the clostridial CoA-dependent pathway is a natural pathway, therefore there is no need to design new reaction or to mine for novel enzymes like 2-oxoglutarate pathway. However, the major limitation of the clostridial CoA-dependent 1-butanol pathway; is the length (six enzymatic steps) of the pathway, which needs more enzymes to be expressed and thus, the cell takes a greater metabolic burden compared with Ehrlich pathway. Another bottleneck in the reconstruction of the clostridial CoA-dependent pathway in the heterologous hosts is the poor expression of oxygen susceptible nature of enzymes [61].

Recently, 2-oxoglutarate pathway of 1-butanol was employed for the production of 1-butanol in E. coli strain. The key advantage of 2-oxoglutarate pathway is the thermodynamically favorable first step to avoid unfavorable condensation of two molecules of acetyl-CoA in comparison to the clostridial pathway [37, 103]. However, using 2-oxoglutarate pathway to produce 1-butanol requires the carboxylation of one phosphoenolpyruvate to oxaloacetate and the activation of 2-hydroxyglutarate to 2-hydroxyglutarylCoA using acetyl-CoA as a donor. These steps need extra energy, which makes the 2-oxoglutarate pathway less advantageous in comparison to clostridial pathway [103].

Another pathway producing 1-butanol is the Ehrlich pathway. The advantages of the Ehrlich pathway is the requirement of only two heterologous enzymatic steps in comparison with 2-oxoglutarate pathway and clostridial pathway, which consist of seven and six enzymatic steps, respectively. Additional advantage of Ehrlich pathway is that it does not need high amount of reducing factor like 2-oxoglutarate and clostridial pathways. Another major advantage of the Ehrlich pathway over CoA-dependent pathway is that it circumvents the production of toxic metabolites, especially CoA-dependent intermediates [95]. However, the production of 1-butanol through the Ehrlich pathway is only 0.8/L (Table 3), which is about a 30-fold lower than CoA-dependent pathway of 1-butanol. One reason of the lower production of 1-butanol via the Ehrlich pathway is the divergence of 2-ketobutyrate (key precursor of 1-butanol) into the isoleucine biosynthetic pathway. Additionally, some of the enzymes involves in threonine biosynthetic pathway are inhibited by their products. Another bottleneck of the Ehrlich pathway is the production of a mixture of alcohols (1-propanol, 2-methyl 1-butanol, isobutanol, 3-methyl 1-butanol and 2-phenyl ethanol), due to the broad substrate specificity of the kivd gene, and thus reduces the overall amount of 1-butanol production [106]. However, it should be noted that most of these alcohols are ideal alternatives to traditional gasoline and are suitable for engine fuel usage.

In summary, the results above demonstrate that the clostridial CoA-dependent pathway performs better among all of the 1-butanol pathways expressed in non-native hosts. Recently, a record high 1-butanol production was achieved by the recombinant strain of C. tyrobutyricum (Table 3) via the CoA-dependent pathway [45], which is higher than that from most of the native 1-butanol producers. Additionally, the engineered strain of E. coli produced 1-butanol to a titer (20 g/L) with yield of 34% (w/w 83% of theoretical yield) in batch fermentation [43], which is at comparable level with 21 g/L of 1-butanol accumulated by adapted native producer C. acetobutylicum strain JB200 [107]. However, some of the non-native hosts produced less amount of 1-butanol. Nevertheless, a considerable room still exists in modifying the existing biosynthetic pathways for 1-butanol production or in the search for the alternative 1-butanol pathways, which are more suitable for expression in non-native hosts.

Current challenges and solutions for 1-butanol production using non-native hosts

Cofactor imbalance

The introduction of a non-native pathway into a microorganism can cause a cofactor imbalance, which results in a metabolic burden on the cells. Therefore, various cofactor engineering strategies have been developed to regulate the redox balance and improve the yield and efficiency of microbial cell factories [108]. To maintain redox balance in the 1-butanol synthetic pathway, four strategies were employed, i.e., regulation of endogenous cofactor systems [37], heterologous cofactor regeneration systems [48], modifying cofactor preferences [60, 109], and synthetic cofactor [32, 49, 110]. For example, endogenous cofactor regeneration strategy and acetyl-CoA were coupled as driving forces to direct the carbon flux in E. coli, through which 1-butanol production was improved to a level comparable to that produced by the Clostridium species, with a 1-butanol titer of 30 g/L and increasing the yield to 70% of the theoretical level [37]. However, in the absence of cofactor regeneration strategy, only the modified metabolic pathway achieved about 10% of the theoretical yield [37]. In another approach, endogenous cofactor regeneration and heterologous cofactor regeneration strategies were employed simultaneously in recombinant E. coli by activating pdh gene anaerobically that encodes pyruvate dehydrogenase complex and with the expression of S. cerevisiae NAD+-dependent formate dehydrogenase (fdh1), which efficiently enhanced the titer of 1-butanol [38]. These results revealed that cofactor engineering is an effective strategy to increase the metabolic flux towards desired products.

Choice of genes

Various recombinant pathways have been constructed for the production of 1-butanol in different microbes. However, the major hurdle facing the non-native hosts is the poor expression of heterologous enzymes. For example, the clostridial 1-butanol pathway is the most employed pathway in the non-native hosts. As aforementioned that the major problem of the clostridial 1-butanol pathway is the poor expression of the oxygen-sensitive enzyme complex (bcd-etf) in non-native hosts and its need for ferredoxin as an additional redox partner. These factors hampered the enzyme activity in the non-native hosts, and thus the expression of bcd-etf complex led towards the production of a very minute quantity of 1-butanol in the non-native hosts. To circumvent the problem of poor expression of enzymes, alternative enzymes were proposed to improve the titers. For example, bcd-etf complex was replaced by ter (encoding trans-enoyl-CoA reductase) gene from Treponema denticola, this gene replacement led to an 18-fold increase in titer of 1-butanol in E. coli after 24 h of fermentation [37, 111]. In another study, the production of 1-butanol was increased more than threefold by replacing the thl gene with E. coli atoB gene due to its higher specific activity for acetyl-CoA than thl [28]. In S. cerevisiae, 1-butanol production was improved by replacing ccr (S. collinus) with ter gene [65]. Similarly, in photosynthetic bacteria such as cyanobacteria, which generates oxygen, the oxygen-sensitive enzymes created various problems in 1-butanol pathway. To solve the oxygen-sensitivity problem of S. elongatus PCC 7942, the bldh was substituted by oxygen-tolerant CoA-acylating aldehyde dehydrogenase (encoded by pdup) from Salmonella enterica in the 1-butanol synthetic pathway. The modified pathway resulted in 1-butanol production to a cumulative titer of 404 mg/L, exceeding the parent strain expressing bldh by 20-fold [61]. These studies demonstrate that the choice of gene is one of the major and deciding factors for enhancing 1-butanol production in the non-native hosts.

Pathway imbalance

Heterologous pathways are usually constructed by the combination of multiple genes from different species. However, transferring the enzymatic pathways from one organism to another often cause a loss of the regulation, and thus imbalances occur in gene expression as well as enzymatic activity [112]. Therefore, several approaches have been developed through which pathway can be balanced, such as promoter engineering, RBS engineering and gene copy number [94, 113, 114]. Promoters are significant genetic elements that play an important role in controlling gene expression in both the heterologous and endogenous pathways. Uncontrolled gene expression in a heterologous host causes a metabolic burden on the cell, and results in the reduction of cellular biomolecules that are important for the growth of the cell itself. Further, it also generates unwanted physiological changes [115]. Therefore, proper promoter selection is essential for smooth growth and high productivity of the desired products. The synthetic pathways should be balanced to direct the flux towards the product. In many cases, lowering the expression of specific enzymes in the pathways is beneficial to achieve higher productivity [116, 117]. This is mostly because some synthetic pathways may accumulate toxic intermediates, which would inhibit cell growth and productivity. Reversibility is another major obstacle in metabolic pathways. Bonds-Watts et al. employed a two-promoter system for 1-butanol production (strong promoter T7 and weak arabinose promoter) to shift the overall equilibrium towards 1-butanol. This shows the importance of appropriate promoter selection in the case of reversibility [94]. In another approach, in S. cerevisiae the production of 1-butanol was increased 100-fold by balancing 1-butanol pathway enzymes through a set of tunable copy number plasmids (which were dependent on antibiotic concentration) [118]. These studies showed that balancing of enzymes in the 1-butanol pathway has a significant role in achieving a high titer of biofuels.

Conclusion and future perspectives

Compared with ethanol, 1-butanol is a superior biofuel and is gaining global research attention in several industrial fields. Native microorganisms are difficult to manipulate for 1-butanol production; however, in recent years, the metabolic engineering of a heterologous host for 1-butanol production has received an enormous amount of research interest with the rapid progress in gene editing and synthetic biology technologies. Various non-native organisms are being equipped with metabolic pathways for converting renewable resources into 1-butanol. Approaches including the use of exogenous enzymes with higher activity, and the removal of competitive pathways have helped in achieving further improvements in 1-butanol production. However, these non-native hosts have limitations such as issues with feedstock, contamination, and toxicity. To overcome these limitations, various microorganisms such as cellulolytic and photosynthetic bacteria, thermophiles, and solvent-tolerant organisms were engineered to produce 1-butanol. However, despite the high potential of these microorganisms, 1-butanol production using these microorganisms still has a far lower titer that is required for commercial production. Therefore, future research should focus on cofactor imbalance, proper promoter and gene selection, product toxicity, and enhancing substrate utilization in order to boost 1-butanol production. Additionally, improving the activity of key metabolic enzymes involved in a 1-butanol pathway by protein engineering is also a promising approach to enhance 1-butanol production. Moreover, lignocellulose or CO2 utilizing microbes are much difficult to engineer than E. coli; therefore, new genetic tools are required to make them industrially feasible.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- ABE:

-

Acetone–butanol–ethanol

- RBS:

-

Ribosome-binding sites

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- GHG:

-

Greenhouse gas

- EMC:

-

Ethylmalonyl-CoA

- ATP:

-

Adenosine triphosphate

- NAD+ :

-

Oxidized nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- NADH:

-

Reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- NADPH:

-

Reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- CoA:

-

Coenzyme A

References

Sarchami T, Rehmann L, Slater SC, Simmons BA, Kaeppler S, Davison BH, Maravelius C, Nookeaw I. Optimizing acid hydrolysis of Jerusalem artichoke-derived inulin for fermentative butanol production. Bioenergy Res. 2015;8:1148–57.

Lapuerta M, Ballesteros R, Barba J. Strategies to introduce n-butanol in gasoline blends. Sustainability. 2017;9:589.

Goyal L, Jalan NK, Khanna S. Butanol tolerant bacteria: isolation and characterization of butanol tolerant Staphylococcus sciuri sp. J Botechnol Res. 2019;10:68–77.

Mascal M. Chemicals from biobutanol: technologies and markets. Biofuel Bioprod Biorefin. 2012;6:483–93.

Capodaglio AG, Bolognesi S. Ecofuel feedstocks and their prospects. In: Azad K, editor. Advances in eco-fuels for a sustainable environment. Sawston: Woodhead Publishing; 2019. p. 15–51.

Bharathiraja B, Jayamuthunagai J, Sudharsanaa T, Bharghavi A, Praveenkumar R, Chakravarthy M, Yuvaraj D. Biobutanol—an impending biofuel for future: a review on upstream and downstream processing tecniques. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 2017;68:788–807.

Kushwaha D, Srivastava N, Mishra I, Upadhyay SN, Mishra PK. Recent trends in biobutanol production. Rev Chem Eng. 2019;35:475.

Kolesinska B, Fraczyk J, Binczarski M, Modelska M, Berlowska J, Dziugan P, Antolak H, Kaminski ZJ, Witonska IA, Kregiel D. Butanol synthesis routes for biofuel production: trends and perspectives. Materials. 2019;12:350.

Xin F, Dong W, Zhang W, Ma J, Jiang M. Biobutanol production from crystalline cellulose through consolidated bioprocessing. Trends Biotechnol. 2019;37:167–80.

Akbar D, Subedi R, Rolfe J, Ashwath N, Rahman A. Reviewing commercial prospects of bioethanol as a renewable source of future energy—an Australian perspective. In: Azad K, editor. Advances in eco-fuels for a sustainable environment. Sawston: Woodhead Publishing; 2019. p. 441–58.

DeCicco JM. Methodological issues regarding biofuels and carbon uptake. Sustainability. 2018;10:1581.

REN21. Renewables, “Global Status Report, REN21 Secretariat, Paris, France”. In Tech. Rep. 2017.

Mařík J, Pexa M, Kotek M, Hönig V. Comparison of the effect of gasoline-ethanol E85-butanol on the performance and emission characteristics of the engine Saab 9-5 2.3 l turbo. Agron Res. 2014;12:359–66.

Gu Y, Jiang Y, Wu H, Liu X, Li Z, Li J, Xiao H, Shen Z, Dong H, Yang Y, Li Y, Jiang W, Yang S. Economical challenges to microbial producers of butanol: feedstock, butanol ratio and titer. Biotechnol J. 2011;11:1348–67.

Green EM. Fermentative production of butanol—the industrial perspective. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2011;22:337–43.

Zheng YN, Li LZ, Xian M, Ma YJ, Yang JM, Xu X, He DZ. Problems with the microbial production of butanol. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;36:1127–38.

Mukhopadhyay A, Keasling JD. Importance of systems biology in engineering microbes for biofuel production. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2008;19:228–34.

Ni Y, Sun Z. Recent progress on industrial fermentative production of acetone–butanol–ethanol by Clostridium acetobutylicum in China. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;83:415–23.

Becerra M, Cerdán M, González-Siso M. Biobutanol from cheese whey. Microb Cell Fact. 2015;14:27.

Qureshi N, Lolas A, Blaschek H. Soy molasses as fermentation substrate for production of butanol using Clostridium beijerinckii BA101. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;26:290–5.

Xin F, Yan W, Zhou J, Wu H, Dong W, Ma J, Zhang W, Jiang M. Exploitation of novel wild type solventogenic strains for butanol production. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2018;11:252.

Sarchami T, Rehmann L. Increased butanol yields through cosubstrate fermentation of Jerusalem artichoke tubers and crude glycerol by Clostridium pasteurianum DSM 525. ACS Omega. 2019;4:15521–9.

Lee SK, Chou H, Ham TS, Lee TS, Keasling JD. Metabolic engineering of microorganisms for biofuels production: from bugs to synthetic biology to fuels. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2008;19:556.

Natalense J, Zouain D. Technology roadmapping for renewable fuels: case of biobutanol in Brazil. J Technol Manag Innov. 2013;8:143–52.

Ranganathan S, Maranas CD. Microbial 1-butanol production: identification of non-native production routes and in silico engineering interventions. Biotechnol J. 2010;5:716–25.

Na D, Yoo S, Chung H, Park H, Park J, Lee S. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli using synthetic small regulatory RNAs. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:170.

Swidah R, Ogunlabi O, Grant CM, Ashe MP. n-Butanol production in S. cerevisiae: co-ordinate use of endogenous and exogenous pathways. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;102:9857–66.

Atsumi S, Cann AF, Connor MR, Shen CR, Smith KM, Brynildsen MP, Chou KJ, Hanai T, Liao JC. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for 1-butanol production. Metab Eng. 2008;10:305–11.

Berezina O, Zakharova N, Brandt A, Yarotsky S, Schwarz W, Zverlov V. Reconstructing the clostridial n-butanol metabolic pathway in Lactobacillus brevis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;87:635–46.

Nielsen D, Leonard E, Yoon S-H, Tseng H-C, Yuan C, Prather K. Engineering alternative butanol production platforms in heterologous bacteria. Metab Eng. 2009;11:262–73.

Lan E, Liao J. Metabolic engineering of cyanobacteria for 1-butanol production from carbon dioxide. Metab Eng. 2011;13:353–63.

Xiaorui Y, Mengmeng X, Shang-Tian Y. Metabolic and process engineering of Clostridium cellulovorans for biofuel production from cellulose. Metab Eng. 2015;32:39–48.

Moon HG, Jang Y-S, Cho C, Lee J, Binkley R, Lee SY. One hundred years of clostridial butanol fermentation. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2016;363:fnw001.

Nanda S, Golemi-Kotra D, McDermott JC, Dalai AK, Gökalp I, Kozinski JA. Fermentative production of butanol: perspectives on synthetic biology. New Biotechnol. 2017;37:210–21.

Ou J, Ma C, Xu N, Du Y, Liu XM. High butanol production by regulating carbon, redox and energy in Clostridia. Front Chem Sci Eng. 2015;9:317–23.

Inui M, Suda M, Kimura S, Yasuda K, Suzuki H, Toda H, Yamamoto S, Okino S, Suzuki N, Yukawa H. Expression of Clostridium acetobutylicum butanol synthetic genes in Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;77:1305–16.

Shen CR, Lan EI, Dekishima Y, Baez A, Cho KM, Liao JC. Driving forces enable high-titer anaerobic 1-butanol synthesis in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:2905–15.

Lim JH, Seo SW, Kim SY, Jung GY. Model-driven rebalancing of the intracellular redox state for optimization of a heterologous n-butanol pathway in Escherichia coli. Metab Eng. 2013;20:56–62.

Mukesh S, Min HC, Chung-Jen C, Yun-Peng C. Potential production platform of n-butanol in Escherichia coli. Metab Eng. 2015;27:76–82.

Saini M, Chiang CJ, Li SY, Chao YP. Production of biobutanol from cellulose hydrolysate by the Escherichia coli coculture system. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2016;363:fnw008.

Chin W-C, Lin K-H, Liu C-C, Tsuge K, Huang C-C. Improved n-butanol production via co-expression of membrane-targeted tilapia metallothionein and the clostridial metabolic pathway in Escherichia coli. BMC Biotechnol. 2017;17:36.

Ohtake T, Pontrelli S, Laviña WA, Liao JC, Putri SP, Fukusaki E. Metabolomics-driven approach to solving a CoA imbalance for improved 1-butanol production in Escherichia coli. Metab Eng. 2017;41:135–43.

Dong H, Zhao C, Zhang T, Zhu H, Lin Z, Tao W, Zhang Y, Li Y. A systematically chromosomally engineered Escherichia coli efficiently produces butanol. Metab Eng. 2017;44:284–94.

Yu M, Zhang Y, Tang IC, Yang ST. Metabolic engineering of Clostridium tyrobutyricum for n-butanol production. Metab Eng. 2011;13:373–82.

Zhang J, Zong W, Hong W, Zhang Z-T, Wang Y. Exploiting endogenous CRISPR-Cas system for multiplex genome editing in Clostridium tyrobutyricum and engineer the strain for high-level butanol production. Metab Eng. 2018;47:49–59.

Yu M, Du Y, Jiang W, Chang WL, Yang ST, Tang IC. Effects of different replicons in conjugative plasmids on transformation efficiency, plasmid stability, gene expression and n-butanol biosynthesis in Clostridium tyrobutyricum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;93:881–9.

Ma C, Kojima K, Xu NN, Mobley J, Zhou LF, Yang ST, Liu XG. Comparative proteomics analysis of high n-butanol producing metabolically engineered Clostridium tyrobutyricum. J Biotechnol. 2015;193:108.

Ma C, Ou J, Xu N, Fierst JL, Yang ST, Liu X. Rebalancing redox to improve biobutanol production by Clostridium tyrobutyricum. Bioengineering. 2015;3:2.

Zhang J, Yu L, Xu M, Yang ST, Yan Q, Lin M, Tang IC. Metabolic engineering of Clostridium tyrobutyricum for n-butanol production from sugarcane juice. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;101:4327–37.

Ou J, Xu N, Ernst P, Ma C, Bush M, Goh KY, Zhao J, Zhou L, Yang ST, Liu X. Process engineering of cellulosic n-butanol production from corn-based biomass using Clostridium cellulovorans. Process Biochem. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procbio.2017.07.009.

Wen Z, Ledesma-Amaro R, Lin J, Jiang Y, Yang S. Improved n-butanol production from Clostridium cellulovorans by integrated metabolic and evolutionary engineering. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2019;85:e02560-02518.

Gaida SM, Liedtke A, Jentges AHW, Engels B, Jennewein S. Metabolic engineering of Clostridium cellulolyticum for the production of n-butanol from crystalline cellulose. Microb Cell Fact. 2016;15:6.

Köpke M, Held C, Hujer S, Liesegang H, Wiezer A, Wollherr A, Ehrenreich A, Liebl W, Gottschalk G, Dürre P. Clostridium ljungdahlii represents a microbial production platform based on syngas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:13087.

Köpke M, Liew F. Production of butanol from carbon monoxide by a recombinant microorganism. WO2012053905A1 2012;53905.

Hu B, Lidstrom ME. Metabolic engineering of Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 for 1-butanol production. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2014;7:1–10.

Wang M, Fan L, Tan T. 1-Butanol production from glycerol by engineered Klebsiella pneumoniae. Rsc Advances. 2014;4:57791–8.

Wang M, Hu L, Fan L, Tan T. Enhanced 1-butanol production in engineered Klebsiella pneumoniae by NADH regeneration. Energy Fuels. 2015;29:1–19.

Bhandiwad A, Shaw AJ, Guss A, Guseva A, Bahl H, Lynd LR. Metabolic engineering of Thermoanaerobacterium saccharolyticum for n-butanol production. Metab Eng. 2014;21:17–25.

Keller MW, Lipscomb GL, Loder AJ, Schut GJ, Kelly RM, Adams MW. A hybrid synthetic pathway for butanol production by a hyperthermophilic microbe. Metab Eng. 2015;27:101–6.

Lan EI, Liao JC. ATP drives direct photosynthetic production of 1-butanol in cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:6018–23.

Lan EI, Ro SY, Liao JC. Oxygen-tolerant coenzyme A-acylating aldehyde dehydrogenase facilitates efficient photosynthetic n-butanol biosynthesis in cyanobacteria. Energy Environ Sci. 2013;6:2672–81.

Fathima AM, Chuang D, Laviña WA, Liao J, Putri SP, Fukusaki E. Iterative cycle of widely targeted metabolic profiling for the improvement of 1-butanol titer and productivity in Synechococcus elongatus. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2018;11:188.

Liu X, Miao R, Lindberg P, Lindblad P. Modular engineering for efficient photosynthetic biosynthesis of 1-butanol from CO2 in cyanobacteria. Energy Environ Sci. 2019;12:2765–77.

Steen EJ, Chan R, Prasad N, Myers S, Petzold CJ, Redding A, Ouellet M, Keasling JD. Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for the production of n-butanol. Microb Cell Fact. 2008;7:36.

Krivoruchko A, Serrano-Amatriain C, Chen Y, Siewers V, Nielsen J. Improving biobutanol production in engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae by manipulation of acetyl-CoA metabolism. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;40:1051–6.

Sakuragi H, Morisaka H, Kuroda K, Ueda M. Enhanced butanol production by eukaryotic Saccharomyces cerevisiae engineered to contain an improved pathway. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2015;79:314–20.

Lian J, Si T, Nair NU, Zhao H. Design and construction of acetyl-CoA overproducing Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains. Metab Eng. 2014;24:139–49.

Branduardi P, Longo V, Berterame NM, Rossi G, Porro D. A novel pathway to produce butanol and isobutanol in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2013;6:68.

Si T, Luo Y, Xiao H, Zhao H. Utilizing an endogenous pathway for 1-butanol production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metab Eng. 2014;22:60–8.

Shi S, Si T, Liu Z, Zhang H, Ang EL, Zhao H. Metabolic engineering of a synergistic pathway for n-butanol production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25675.

Yu A, Zhao Y, Pang Y, Hu Z, Zhang C, Xiao D, Chang MW, Leong SSJ. An oleaginous yeast platform for renewable 1-butanol synthesis based on a heterologous CoA-dependent pathway and an endogenous pathway. Microb Cell Fact. 2018;17:166.

Kunze G, Hähnel U. Production of butanol by fermentation in Arxula sp. Leibniz-Institut für Pflanzengenetik und Kulturpflanzenforschung (IPK) Patent no. EP 2012;2508597.

Al-Shorgani NKN, Al-Tabib AI, Kadier A, Zanil MF, Lee KM, Kalil MS. Continuous butanol fermentation of dilute acid-pretreated de-oiled rice bran by Clostridium acetobutylicum YM1. Sci Rep. 2019;9:4622.

Xue C, Zhao J, Chen L, Yang S-T, Bai F. Recent advances and state-of-the-art strategies in strain and process engineering for biobutanol production by Clostridium acetobutylicum. Biotechnol Adv. 2017;35:310–22.

Kovács K, Willson BJ, Schwarz K, Heap JT, Jackson A, Bolam DN, Winzer K, Minton N. Secretion and assembly of functional mini-cellulosomes from synthetic chromosomal operons in Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2013;6:117.

Sabourin-Provost G, Hallenbeck PC. High yield conversion of a crude glycerol fraction from biodiesel production to hydrogen by photofermentation. Bioresour Technol. 2009;100:3513–7.

Vasconcelos I, Girbal L, Soucaille P. Regulation of carbon and electron flow in Clostridium acetobutylicum grown in chemostat culture at neutral pH on mixtures of glucose and glycerol. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1443–50.

Sarchami T, Johnson E, Rehmann L. Optimization of fermentation condition favoring butanol production from glycerol by Clostridium pasteurianum DSM 525. Bioresour Technol. 2016;208:73–80.

Weissermel K, Arpe H-J. Industrial organic chemistry. New York: Wiley; 2008.

Bertsch J, Müller V. Bioenergetic constraints for conversion of syngas to biofuels in acetogenic bacteria. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2015;8:210.

Sponza DT, Vural C, Güney G. Biofuel production from carbon dioxide gas in polluted areas. In: Balkaya N, Guneysu S, editors. Recycling and reuse approaches for better sustainability. Berlin: Springer; 2019. p. 127–39.

Behera S, Sharma NK, Kumar S. Prospects of solvent tolerance in butanol fermenting bacteria. In: Kumar S, Sani RK, editors. Biorefining of biomass to biofuels. Berlin: Springer; 2018. p. 249–64.

Alper H, Stephanopoulos G. Global transcription machinery engineering: a new approach for improving cellular phenotype. Metab Eng. 2007;9:258–67.

Knoshaug EP, Zhang M. Butanol tolerance in a selection of microorganisms. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2009;153:13–20.

Mann MS, Dragovic Z, Schirrmacher G, Lütke-Eversloh T. Over-expression of stress protein-encoding genes helps Clostridium acetobutylicum to rapidly adapt to butanol stress. Biotechnol Lett. 2012;34:1643–9.

Rühl J, Schmid A, Blank LM. Selected Pseudomonas putida strains able to grow in the presence of high butanol concentrations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:4653–6.

Zaki A, Wimalasena T, Greetham D. Phenotypic characterisation of Saccharomyces spp. for tolerance to 1-butanol. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;41:1627–36.

Kataoka N, Tajima T, Kato J, Rachadech W, Vangnai AS. Development of butanol-tolerant Bacillus subtilis strain GRSW2-B1 as a potential bioproduction host. AMB Express. 2011;1:10.

Mougiakos I, Bosma EF, Weenink K, Vossen E, Goijvaerts K, van der Oost J, van Kranenburg R. Efficient genome editing of a facultative thermophile using mesophilic spCas9. ACS Synth Biol. 2017;6:849–61.

Lynd LR, Weimer PJ, Van Zyl WH, Pretorius IS. Microbial cellulose utilization: fundamentals and biotechnology. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2002;66:506–77.

Servinsky MD, Kiel JT, Dupuy NF, Sund CJ. Transcriptional analysis of differential carbohydrate utilization by Clostridium acetobutylicum. Microbiology. 2010;156:3478–91.

Lin L, Song H, Tu Q, Qin Y, Zhou A, Liu W, He Z, Zhou J, Xu J. The Thermoanaerobacter glycobiome reveals mechanisms of pentose and hexose co-utilization in bacteria. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002318.

Shaw AJ, Hogsett DA, Lynd LR. Natural competence in Thermoanaerobacter and Thermoanaerobacterium species. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:4713–9.

Bondwatts BB, Bellerose RJ, Chang MC. Enzyme mechanism as a kinetic control element for designing synthetic biofuel pathways. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:222–7.

Shen CR, Liao JC. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for 1-butanol and 1-propanol production via the keto-acid pathways. Metab Eng. 2008;10:312–20.

Atsumi S, Liao JC. Directed evolution of Methanococcus jannaschii citramalate synthase for biosynthesis of 1-propanol and 1-butanol by Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:7802–8.

Bourque D, Pomerleau Y, Groleau D. High-cell-density production of poly-β-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) from methanol by Methylobacterium extorquens: production of high-molecular-mass PHB. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1995;44:367–76.

Schrader J, Schilling M, Holtmann D, Sell D, Filho MV, Marx A, Vorholt JA. Methanol-based industrial biotechnology: current status and future perspectives of methylotrophic bacteria. Trends Biotechnol. 2009;27:107–15.

Sonntag F, Müller JE, Kiefer P, Vorholt JA, Schrader J, Buchhaupt M. High-level production of ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway-derived dicarboxylic acids by Methylobacterium extorquens under cobalt-deficient conditions and by polyhydroxybutyrate negative strains. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99:3407–19.

Rémi P, Kathrin S, Patrick K, Stéphane M, Vorholt JA, Jean-Charles P. Genome-scale reconstruction and system level investigation of the metabolic network of Methylobacterium extorquens AM1. BMC Syst Biol. 2011;5:189.

Schneider K, Peyraud R, Kiefer P, Christen P, Delmotte N, Massou S, Portais J-C, Vorholt JA. The ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway is used in place of the glyoxylate cycle by Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 during growth on acetate. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:757–66.

Hu B, Yang Y-M, Beck DA, Wang Q-W, Chen W-J, Yang J, Lidstrom ME, Yang S. Comprehensive molecular characterization of Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 adapted for 1-butanol tolerance. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2016;9:84.

Ferreira S, Pereira R, Liu F, Vilaça P, Rocha I. Discovery and implementation of a novel pathway for n-butanol production via 2-oxoglutarate. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2019;12:230.

Mattam AJ, Yazdani SS. Engineering E. coli strain for conversion of short chain fatty acids to bioalcohols. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2013;6:128.

Noguchi S, Putri SP, Lan EI, Laviña WA, Dempo Y, Bamba T, Liao JC, Fukusaki E. Quantitative target analysis and kinetic profiling of acyl-CoAs reveal the rate-limiting step in cyanobacterial 1-butanol production. Metabolomics. 2016;12:26.

Atsumi S, Hanai T, Liao JC. Non-fermentative pathways for synthesis of branched-chain higher alcohols as biofuels. Nature. 2008;451:86–9.

Xu M, Zhao J, Le Y, Tang IC, Xue C, Yang ST. Engineering Clostridium acetobutylicum with a histidine kinase knockout for enhanced n-butanol tolerance and production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99:1011–22.

Chen X, Li S, Liu L. Engineering redox balance through cofactor systems. Trends Biotechnol. 2014;32:337–43.

Tian L, Conway PM, Cervenka ND, Cui J, Maloney M, Olson DG, Lynd LR. Metabolic engineering of Clostridium thermocellum for n-butanol production from cellulose. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2019;12:186.

Du Y, Jiang W, Yu M, Tang IC, Yang ST. Metabolic process engineering of Clostridium tyrobutyricum Δack-adhE2 for enhanced n-butanol production from glucose: effects of methyl viologen on NADH availability, flux distribution, and fermentation kinetics. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2015;112:705–15.

Buelter T, Hawkins A, Kersh K, Meinhold P, Peters M, Subbian E. Engineered microorgansims for production n-butanol and related methods. US Patent Application. 11/949,724; 2009.

Pitera DJ, Paddon CJ, Keasling JD, Newman JD. Balancing a heterologous mevalonate pathway for improved isoprenoid production in Escherichia coli. Metab Eng. 2007;9:193–207.

Pontrelli S, Fricke RCB, Sakurai SSM, Putri SP, Fitz-Gibbon S, Chung M, Wu H-Y, Chen Y-J, Pellegrini M, Fukusaki E, Liao JC. Directed strain evolution restructures metabolism for 1-butanol production in minimal media. Metab Eng. 2018;49:153–63.

Salis HM, Mirsky EA, Voigt CA. Automated design of synthetic ribosome binding sites to control protein expression. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:946–50.

Rahman Z, Nawab J, Sung BH, Kim SC. A critical analysis of bio-hydrocarbon production in bacteria: current challenges and future directions. Energies. 2018;11:1–14.

Parayil Kumaran A, Wen-Hai X, Tyo KEJ, Yong W, Fritz S, Effendi L, Oliver M, Too Heng P, Blaine P, Gregory SJS. Isoprenoid pathway optimization for Taxol precursor overproduction in Escherichia coli. Science. 2010;330:70–4.

Pfleger B, Pitera D, Smolke C, Keasling J. Combinatorial engineering of intergenic regions in operons tunes expression of multiple genes. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1027.

Lian J, Jin R, Zhao H. Construction of plasmids with tunable copy numbers in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and their applications in pathway optimization and multiplex genome integration. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2016;113:2462–73.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Adil Farooq Lodhi from Beijing Institute of Technology, China for his comments and suggestions on the writing.

Funding

This work was jointly supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2019YFA0906500), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 91951113) and the Innovation Team Project of Colleges and Universities in Jinan (Grant No. 2019GXRC033).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XM and YH conceived the topic. SN, NW, XM and YH collected necessary literatures and wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Nawab, S., Wang, N., Ma, X. et al. Genetic engineering of non-native hosts for 1-butanol production and its challenges: a review. Microb Cell Fact 19, 79 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-020-01337-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-020-01337-w