Abstract

Background

Captive wild animals in zoos infected with Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, Enterocytozoon bieneusi, and Blastocystis sp. can be sources of zoonotic infections and diseases. Therefore, to investigate the distribution of these pathogens in captive wild animals of zoos in Henan, China, a total of 429 fresh fecal samples were collected from six zoos in Henan, China. The infection rates of Cryptosporidium spp., G. duodenalis, E. bieneusi, and Blastocystis sp. were determined by PCR analysis of corresponding loci. Positive results for Cryptosporidium (C. parvum and C. hominis) were subtyped based on the (gp60) gene.

Results

The overall prevalence was 43.1% (185/429), and the prevalence of Cryptosporidium, Giardia duodenalis, Enterocytozoon bieneusi, and Blastocystis sp. were 2.8% (12/429), 0.5% (2/429), 20.8% (89/429), and 19.1% (82/429), respectively. Five Cryptosporidium species, namely, C. hominis, C. parvum, C. muris, C. andersoni, and C. macropodum, were identified in this study. Cryptosporidium parvum was further subtyped as IIdA19G1. Two Giardia duodenalis assemblages (A and E) were also identified. A total of 20 Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes were detected, including 18 known (BEB6, D, HND-1, CD7, SDD1, Henan-IV, KIN-1, CHK1, Peru8, Henan-V, CHG11, CHG-1, CHS9, CHG21, Type-IV, CHC9, CM5, and CHB1) and 2 novel genotypes (CHWD1 and CHPM1). A total of nine subtypes of Blastocystis sp. (ST1, ST2, ST3, ST5, ST6, ST7, ST10, ST13, and ST14) were identified in captive wild animals in zoos in the present study. Cryptosporidium andersoni, nine Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes, and five Blastocystis subtypes were here first identified in new hosts.

Conclusions

Our study has expanded the host ranges of these four pathogens. The data indicate that animals in zoos can commonly be infected with these four zoonotic pathogens, and animals in zoos are potential sources of zoonotic infections in humans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, Enterocytozoon bieneusi, and Blastocystis sp. are four common opportunistic pathogens with wide host ranges that include livestock, wildlife, and humans [1,2,3,4]. Infections with these pathogens can cause diarrhea and several other gastrointestinal illnesses in humans and animals [1,2,3,4]. The fecal-oral route is the main transmission pathway of the four pathogens, and infection can also result from contaminated food or water [2, 4].

Currently, at least 44 valid species and about 70 genotypes of Cryptosporidium have been described, and at least 20 species and 5 genotypes have been detected in humans [4, 5]. Giardia duodenalis is considered a species complex with at least eight distinct assemblages (A-H), and assemblages A and B are infectious to humans and other mammals as well as a wide range of hosts [6]. Over 474 Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes were distributed in several genetically isolated populations comprising 11 major groups in a phylogenetic analysis, including zoonotic group 1 and several host-adapted groups [3, 7]. Among 17 approved subtypes (ST1-ST17) of Blastocystis sp., ST1–ST9 and ST12 have been observed in humans. Two subtypes (ST9 and ST12) are specific to humans, and the remaining subtypes have been detected in non-human hosts [8, 9].

For many animal species, life in a zoo is very different from natural free-range conditions. Due to the limitations of living space, the prevalence of parasites in captive animals is often higher than that of wild animals [10]. Animal keepers can be in close contact with animals through feeding, washing, and cleaning, and visitors can indirectly contact animals by petting or by giving food. Previous studies have found Cryptosporidium and Blastocystis in zoo animals and their keepers [11,12,13]. There is a potential for zoonotic transmission between animals and humans in zoos [14]. The objectives of this study are to examine the prevalence and determine the genetic distributions of Cryptosporidium, G. duodenalis, E. bieneusi, and Blastocystis and to identify genotypes/assemblages of human health importance..

Results

Occurrence of Cryptosporidium, Giardia duodenalis, Enterocytozoon bieneusi, and Blastocystis

The overall infection rate was 43.1% (185/429, 95% CI: 39.33–48.77%, χ2 = 25.048, df = 5, P < 0.001) among six zoos. The prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, Enterocytozoon bieneusi, and Blastocystis sp. were 2.8% (12/429, 95% CI: 1.23–4.36%, χ2 = 23.613, df = 5, P < 0.001), 0.5% (2/429, 95% CI: 0–1.11%, χ2 = 21.936, df = 5, P < 0.001), 20.8% (89/429, 95% CI: 16.89–24.59%, χ2 = 25.877, df = 5, p < 0.001), and 19.1% (82/429, 95% CI: 16.24–23.85%, χ2 = 7.696, df = 5, p > 0.05), respectively (Table 1). Co-infection results showed that 29 samples were infected by two kinds of parasites; the infected species were sika deer (n = 6), white kangaroos (n = 4), macaques (n = 4), black-and-white colobus monkeys (n = 3), two giraffes (n = 2), a Bactrian camel (n = 1), a patas monkey (n = 1), a peafowl (n = 1), a pony (n = 1), a leopard (n = 1), a golden sub-nosed monkey (n = 1), a white-browed monkey (n = 1), a green monkey (n = 1), a squirrel monkey (n = 1), and a northern pigtail macaque (n = 1).

Cryptosporidium species and subtypes

Five Cryptosporidium species, namely C. hominis, C. parvum, C. andersoni, C. muris, and C. macropodum were identified in this study (Table 2). The Cryptosporidium hominis and C. parvum samples were further subtyped based on gp60 gene sequence analysis, with all C. parvum identified as subtype IIdA19G1. Cryptosporidium hominis was not successfully identified. The three gp60 sequences showed 99.7% nucleotide sequence identity to the isolates from dairy cattle (MF074761) and Homo sapiens (JQ796092) from China.

Giardia duodenalis assemblages

Two Giardia duodenalis assemblages, A and E were detected based on SSU rRNA and gdh loci (Table 2). Assemblage A shared 100% similarity with the sequence from Brazilian Panthera (HM134217), and Assemblage E was identical to the isolate derived from dairy cattle in China (KF843926).

Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes

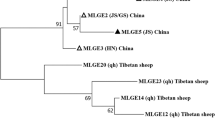

A total of 20 genotypes of Enterocytozoon bieneusi were identified in the present study, including 18 known genotypes: BEB6, D, HND-1, CD7, SDD1 Henan-IV, KIN-1, CHK1, Peru8, Henan-V, CHG11, CHG-1, CHS9, CHG21, Type-IV, CHC9, CM5, and CHB1. However, a novel genotype CHPM1 was found in a patas monkey, and CHWD1 was found in a white-lipped deer. Additionally, SDD1, BEB6, CD7, HDN-1, CHG-1, CHC9, D, Peru8, and Type-IV were identified for the first time in animal hosts. The most prevalent E. bieneusi genotype was BEB6 (32/89, 36.0%) followed by D (16/89, 18.0%) (Table 3). Compared with genotype D (KX383624), novel genotypes CHPM1 and CHWD1 had one and three SNPs based on the ITS region, respectively (Table S2). Phylogenetic analysis of E. bieneusi showed that genotypes D, Peru8, SDD1, HND-I, Type-IV, KIN-1, Henan-IV, Henan-V, CHPM1, and CHWD1 were clustered in Group 1, whereas CHG11, CHG-1, BEB6, CM5, CHC9, and CHS9 were clustered into Group 2. CHG21, CD7 and CHB1, CHK1were clustered into Group 9, Group 11 and Group10, respectively (Fig. 1).

Locations where specimens were collected in this study. The figure was originally designed by the authors using the software ArcGIS 10.2. No copyright permission was required. The original vector diagram imported in ArcGIS was adapted from Natural Earth (http://www.naturalearthdata.com)

Blastocystis subtypes

A total of nine Blastocystis subtypes were found, including ST1, ST2, ST3, ST5, ST6, ST7, ST10, ST13, and ST14. However, the other six subtypes were identified in new hosts for the first time: ST2, ST3, ST5, ST6, ST7, and ST10 were detected in ponies, an orangutan, a gorilla, sika deer, white kangaroos, a blue eared-pheasant, a whooper swan, and giraffes. The most prevalent Blastocystis subtype was ST5 (19/86, 22.1%) followed by ST10 (18/86, 20.1%) (Table 4).

Discussion

In the present study, the Cryptosporidium prevalence was 2.8%, which is lower than the rates (70.0%) reported in Xining Zoo in China [15] and zoo mammals (35.8%) in Barcelona, Spain [16]. However, the infection rate was higher than those in zoos (2.0%) in Alberta and Manitoba of Canada [17] and Zhengzhou Zoo (1.6%) in China [18]. For Giardia duodenalis, the prevalence was 0.5%, which is lower than the rate found in most studies conducted in zoos worldwide, for example the 2.5% in Zhengzhou Zoo in China [18], 3.3% in the zoo in Aprilia, Italy [19], and 24.0% in a zoological garden in Poland [20]. The overall infection rate of E. bieneusi was 20.8%, lower than in a previous study conducted in the zoo (32.5%) of Howard County in America [21] and higher than in Zhengzhou Zoo (15.8%) in China [18]. Concerning Blastocystis, the infection rate was 19.1%, which was higher than the 6.6% found in four zoos in Italy [21] and 12.3% in a zoological garden in Poland [20]. In contrast, the prevalence was lower than that (40.2%) in Qinling Zoo in China [8]. Infection rates may be influenced by many factors, including the zoo management model, living conditions, the immune status of the animals, climate, and geography.

This study demonstrates a high sample prevalence and diversity of intestinal parasites in captive wild animals in zoos in Henan, China. The present study indicated that Giardia duodenalis was only found in Kaifeng Zoo, and Cryptosporidium spp. was found in Kaifeng Zoo and Swan Lake Zoo. Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Blastocystis sp. were found in 6 zoos. It can be concluded that Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Blastocystis sp. are common in some zoos in Henan Province, and among the 6 zoos, the infection rate of Enterocytozoon bieneusi is different. The highest infection rate is Zhengzhou Zoo and the lowest is Kaifeng Zoo. The result of Blastocystis sp. is consistent with E. bieneusi. So the prevalence and diversity varied with geographic region.

Zoonotic Cryptosporidium species (C. hominis, C. parvum, C. muris, and C. andersoni) and C. macropodum were identified in the present study. Cryptosporidium hominis and C. parvum are responsible for most cases of cryptosporidiosis in humans [22, 23]. Cryptosporidium parvum subtyping revealed IIdA19G1 in our study that has previously been found in humans, dairy cattle, and yaks in China [24]. Since the first report of C. muris in human samples in 2000, evidence of human infection with C. muris has been accumulating [25]. Including diarrhea patients cattle, sheep, and the cactus mouse [24, 26], C. andersoni was found in a south China tiger in the present study, thereby expanding the host range of C. andersoni. Cryptosporidium macropodum (only detected in Australia previously) [27] was detected for the first time in a white kangaroo in China.

Similar to previous reports [28], we identified two G. duodenalis assemblages (A and E) in the Bactrian camel. Assemblage A was one of the two species of G. duodenalis most commonly detected in human samples, and this assemblage has also been detected in livestock, companion animals, and non-human primates (NHPs) [2]. Assemblage E has been reported as an assemblage with host specificity, mainly infecting cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs. However, there are still some studies reporting the presence in human [29]. Therefore, the data indicate that animals in these zoos may serve as reservoirs of G. duodenalis assemblages with the potential for zoonotic infection in humans. However, this speculation needs further research and data to confirm.

A total of 20 Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes were observed in 89 positive specimens. BEB6 was the predominant E. bieneusi genotype in the current study; it has been found in NHPs, sheep and goats, companion animals (cats and dogs), chinchillas, rabbits, meerkats, and bats. The genotypes D, type IV, and Peru8 were previously detected in humans, goats, pigs, and NHPs, and they have been frequently found in different water sources, suggesting the likelihood of zoonotic or waterborne transmission [30,31,32,33]. Indeed, previous reports have found genotype BEB6, D, type IV, and Peru8 in humans and wildlife in various countries [22, 34, 35]. Therefore, these findings indicate that zoonotic transmission to humans and between wildlife species may occur in the zoos investigated in the present research. We also found the newly identified genotypes CHPM1and CHWD1 in white-lipped deer and patas monkeys, respectively. Interestingly, the isolation of novel genotypes from white-lipped deer, as well as the three novel genotypes identified by the study of Li et al., suggest that genetic variability in deer-derived E. bieneusi may be common [3]. Phylogenetic analysis showed that genotypes D, Peru8, SDD1, HND-I, Type-IV, KIN-1, Henan-IV, Henan-V, CHPM1, and CHWD1 were clustered in Group 1, which was composed of zoonotic genotypes. Genotypes CHG11, CHG-1, BEB6, CM5, CHC9, and CHS9 were clustered in Group 2, and other data indicated that the genotypes in Group 2 may have zoonotic potential. Accumulating evidence indicates that some Group 2 genotypes (I, J, BEB4, and BEB6) can also be detected in humans.

A total of nine subtypes were detected in Blastocystis, including ST1, ST2, ST3, ST5, ST6, ST7, ST10, ST13, and ST14. Studies indicated that ST1 to ST9 and ST12 have the ability to infect humans [8]. For example, ST1, ST3, and ST5 have been found in NHPs and their keepers, in southern hairy-nosed wombats and their keepers, and in pigs and their workers, respectively [12, 13]. Although the fecal samples of animal keepers were not considered in the present study, the possibility of transmission between animals and animal keepers is undeniable. Therefore, subtypes ST1, ST2, ST3, and ST5 may have potential risk for zoonotic transmission between animals and humans. Present study indicated that the dominant species of Blastocystis subtypes in NHPs is ST1-ST3, which is consistent with other results [36,37,38,39]. In addition, we found that ostriches can be infected by ST5, a subtype that has been isolated sporadically from many other animals, including NHPs, camels, the black rhinoceros, and rodents [13, 40]. ST6 was found in blue-eared pheasant and peafowl, and ST7 was found in turkeys and the whooper swan, similar to previous findings [36]. ST10 was previously identified in fallow deer and camels [41]. Similarly, ST10 was detected in sika deer and yellow deer in the present study. Only ST14 was found in Bactrian camels here, which is consistent with previous findings [36]. The above results demonstrate that these subtypes can infect animal species in zoos as well as humans, and thus more attention should be paid to these parasites.

Some species, genotypes and subtypes of these parasites were detected in some new hosts in present study. However, what can not be determined is that whether these animals are natural hosts or carriers of theses pathogens and whether these parasites can cause infections in new hosts. Animals could get infected via eating food or drinking water which contain viable pathogens. Considering the specificity of zoo environment, where different species of animals are kept in seperate areas, the risk of cryptosporidiosis transmission through contaminated food or water seems relatively low. Due to the rarity of wild captive animals and the limitation of the amount of pathogen infection, it is difficult for us to demonstrate cross-transmission in different species of wild captive animals. We only successfully infected BALB/c mice with the oocysts of C. muris [42]. Efforts should be made in the following study to conduct more investigative research on these problems.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that animals in zoos can be infected with human pathogenic Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, Enterocytozoon bieneusi, and Blastocystis sp. These animals can serve as reservoirs of human cryptosporidiosis, giardiasis, microsporidiosis, and blastocystosis. Effort should be made to conduct more experimental work to reveal the genetic characteristics and assess the zoonotic risks of these parasites.

Methods

Study area and sample collection

Between October 2018and June 2020, a total of 429 fresh fecal samples (77 animal species) were collected from captive animals in 6 zoos in Henan, China; these were Xinxiang Zoo (n = 23), Kaifeng Zoo (n = 36), Luoyang Zoo (n = 27), Shangqiu Zoo (n = 24), Jiaozuo Swan Lake Zoo (n = 120) (private zoo), and Zhengzhou Zoo (n = 199) (Fig. 2). Some of the specimens tested in this study were animals imported from abroad and were ill (slight or severe diarrhea, and some adult worms in fecal samples) (Table S1). One specimen per animal was used in this study. Only the central portion of the fecal material was collected during sampling to ensure no environmental contamination. Each fresh sample was collected into a sterile glove, labeled, and placed into a container with ice packs and immediately sent to the lab for DNA extraction.

Neighbor-joining tree of Enterocytozoon bieneusi ITS genotypes. Phylogenetic relationships of ITS nucleotide sequences of the Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes identified in this study and other reported genotypes. The phylogeny was inferred by a neighbor-joining analysis. Bootstrap values were obtained using 1000 replicates; those with values > 50% are shown on the nodes. The genotypes in this study are marked by empty triangles, and the novel genotypes are marked by filled triangles

DNA extraction

200 mg of fecal samples were used to extract DNA with an E.Z.N.A.® Stool DNA Kit (Onmega Biotek Inc., Norcross, GA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the extracted DNA was stored at − 20 °C before PCR analysis. The quality of the DNA extracted was determined by using the NanoDrop absorbance ratio.

PCR amplification

All of the samples were amplified by nested PCR to identify Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia duodenalis based on the small subunit (SSU) rRNA gene and the glutamate dehydrogenase (gdh) gene [43, 44], respectively. Positives for Cryptosporidium (C. parvum and C. hominis) were subtyped based on the 60-kDa glycoprotein (gp60) gene [45]. Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Blastocystis sp. were identified based on the ITS region [46] and the SSU rRNA gene [47], respectively (Table S3). The amplification was performed in 25 μL reaction mixtures. The first reaction mixture contained 1 μL of extracted DNA. The second reaction mixture contained 1 μL of the first PCR amplification product. The KOD Plus DNA polymerase (Toyobo Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) was used for all PCR amplification. Positive and negative control samples (distilled water) were included in each PCR assay, and two replicates of each PCR were run for all of the samples. The final PCR products were subjected to 1.0% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by staining with DNAGREEN (Tiandz, Inc., Beijing, China).

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

All of the final positive PCR products were sequenced using the ABI PRISM™ 3730 XL DNA Analyzer with the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), and two-directional sequencing was used to ensure accuracy. To identify different species or genotypes, sequences obtained were aligned with the reference sequences in GenBank (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) using the software Clustal X 2.1 (http://www.clustal.org/). The phylogenetic relationships of E. bieneusi genotypes were analyzed by the neighbor-joining algorithm in MEGA 7.0 (http://www.megasoftware.net/). Bootstrap values were calculated by analyzing 1000 replicates. The established nomenclature system was used in the naming of E. bieneusi ITS genotypes [48].

Statistical analysis

The infection rates with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated by Wald’s method in SPSS 22.0 version (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Differences in corresponding infection rates among locations were examined by the Chi-square test, and differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Availability of data and materials

All of the data used or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Representative nucleotide sequences have been deposited in GenBank, including Cryptosporidium spp., gp60 (MT899227–MT899229), G. duodenalis, E. bieneusi, and Blastocystis sp.. Accession numbers of Cryptosporidium spp., G. duodenalis, E. bieneusi and Blastocystis sp. found in Tables 2, 3 and 4.

Abbreviations

- SSU rRNA:

-

Small subunit rRNA

- gp60 :

-

The 60 kDa glycoprotein gene

- gdh :

-

Glutamate dehydrogenase gene

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- NJ:

-

Neighbor-Joining

- NHPs:

-

Non-human primates

- ITS:

-

Internal transcribed spacer

References

Clark CG, van der Giezen M, Alfellani MA, Stensvold CR. Recent developments in Blastocystis research. Adv Parasitol. 2013;82:1–32 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407706-5.00001-0.

Feng Y, Xiao L. Zoonotic potential and molecular epidemiology of Giardia species and giardiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:110–40 https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00033-10.

Li W, Feng Y, Santin M. Host specificity of Enterocytozoon bieneusi and public health implications. Trends Parasitol. 2019;35:436–51 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2019.04.004.

Xiao L. Molecular epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis: an update. Exp Parasitol. 2010;124:80–9 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exppara.2009.03.018.

Holubová N, Tmová L, Sak B, Hejzlarová A, Konečný R, McEvoy J, et al. Description of Cryptosporidium ornithophilus n. sp. (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) in farmed ostriches. Parasites Vectors. 2020;13:340 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04191-2.

Sprong H, Cacciò SM, Giessen J W B V D. Identification of zoonotic genotypes of Giardia duodenalis. PLoS Neglect Trop D. 2009;3:e558 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0000558.

Thellier M, Breton J. Enterocytozoon bieneusi in human and animals, focus on laboratory identification and molecular epidemiology. Parasite (Paris, France). 2008;15:349–58 https://doi.org/10.1051/parasite/2008153349.

Zhao GH, Hu XF, Liu TL, Hu RS, Yu ZQ, Yang WB, et al. Correction to: molecular characterization of Blastocystis sp. in captive wild animals in Qinling Mountains. Parasitol Res. 2018;117:343–4 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-017-5692-7.

Jiménez PA, Jaimes JE, Ramírez JD. A summary of Blastocystis subtypes in north and South America. Parasite Vector. 2019;12:376 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3641-2.

Panayotova-Pencheva MS. Parasites in captive animals: a review of studies in some European zoos. Der Zoologische Garten. 2013;82:60–71 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.zoolgart.2013.04.005.

Sazmand A, Rasooli A, Nouri M, Hamidinejat H, Hekmatimoghaddam S. Prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. in camels and involved people in Yazd Province. Iran. Iran J Parasitol. 2012;7:80–4 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ttbdis.2012.02.002.

Parkar U, Traub RJ, Vitali S, Elliot A, Levecke B, Robertson I, et al. Molecular characterization of Blastocystis isolates from zoo animals and their animal-keepers. Vet Parasitol. 2010;169:8–17 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.12.032.

Wang W, Owen H, Traub RJ, Cuttell L, Inpankaew T, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H. Molecular epidemiology of Blastocystis in pigs and their in-contact humans in Southeast Queensland, Australia, and Cambodia. Vet Parasitol. 2014;203:264–9 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.04.006.

Erdozain G, KuKanich K, Chapman B, Powell D. Observation of public health risk behaviours, risk communication and hand hygiene at Kansas and Missouri petting zoos--2010-2011. Zoonoses Public Health. 2013;60:304–10 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1863-2378.2012.01531.x.

Karanis P, Plutzer J, Halim NA, Igori K, Nagasawa H, Ongerth J, et al. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium from animal sources in Qinghai province of China. Parasitol Res. 2007;101:1575–80 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-007-0681-x.

Gómez MS, Torres J, Gracenea M, Fernandez-Morán J, Gonzalez-Moreno O. Further report on Cryptosporidium in Barcelona zoo mammals. Parasitol Res. 2000;86:318–23 https://doi.org/10.1007/s004360050049.

Conrad CC, Stanford K, Narvaez-Bravo C, Neumann NF, Munns K, Tymensen L, et al. Zoonotic fecal pathogens and antimicrobial resistance in Canadian petting zoos. Microorganisms. 2018;6:70 https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms6030070.

Li J, Qi M, Chang Y, Wang R, Li T, Dong H, et al. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in captive wildlife at Zhengzhou zoo, China. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2015;62:833–9 https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms6030070.

Capasso M, Maurelli MP, Ianniello D, Alves LC, Amadesi A, Laricchiuta P, et al. Use of Mini-FLOTAC and fill-FLOTAC for rapidly diagnosing parasitic infections in zoo mammals. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2019;28:168–71 https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-296120180087.

Maesano G, Capasso M, Ianniello D, Cringoli G, Rinaldi L. Parasitic infections detected by FLOTAC in zoo mammals from Warsaw, Poland. Acta Parasitol. 2014;59:343–53 https://doi.org/10.2478/s11686-014-0249-8.

Santin M, Fayer R. Enterocytozoon bieneusi, Giardia, and Cryptosporidium infecting white-tailed deer. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2015;62:34–43 https://doi.org/10.1111/jeu.12155.

Wang L, Zhang H, Zhao X, Zhang L, Zhang G, Guo M, et al. Zoonotic Cryptosporidium species and Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes in HIV-positive patients on antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:557–63 https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.02758-12.

Khan A, Shaik JS, Grigg ME. Genomics and molecular epidemiology of Cryptosporidium species. Acta Trop. 2018;184:1–14 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.10.023.

Wang R, Zhao G, Gong Y, Zhang L. Advances and perspectives on the epidemiology of bovine Cryptosporidium in China in the past 30 years. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1823 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01823.

Katsumata T, Hosea D, Ranuh IG, Uga S, Yanagi T, Kohno S. Short report: possible Cryptosporidium muris infection in humans. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62:70–2 https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.90.1.139.

Jiang Y, Ren J, Yuan Z, Liu A, Zhao H, Liu H, et al. Cryptosporidium andersoni as a novel predominant Cryptosporidium species in outpatients with diarrhea in Jiangsu Province, China. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14(1):1–6 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-014-0555-7.

Zahedi A, Monis P, Aucote S, King B, Paparini A, Jian F, et al. Zoonotic Cryptosporidium Species in Animals Inhabiting Sydney Water Catchments. PLos One. 2016;11(12) https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0168169.

Minetti C, Taweenan W, Hogg R, Featherstone C, Randle N, Latham SM, et al. Occurrence and Diversity of Giardia duodenalis Assemblages in Livestock in the UK. Transbound Emergz dis. 2016;61(6) https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.12075.

Ryan U, Cacciò SM. Zoonotic potential of Giardia. Int J Parasitol. 2013;43:943–56 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2013.06.001.

Zhang Z, Huang J, Karim MR, Zhao J, Dong H, Ai W, et al. Zoonotic Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes in pere David's deer (Elaphurus davidianus) in Henan, China. Exp Parasitol. 2015;155:46–8 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exppara.2015.05.008.

Shi K, Li M, Wang X, Li J, Karim MR, Wang R, et al. Molecular survey of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in sheep and goats in China. Parasite Vector. 2016;9:23 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1304-0.

Karim MR, Dong H, Yu F, Jian F, Zhang L, Wang R, et al. Genetic diversity in Enterocytozoon bieneusi isolates from dogs and cats in China: host specificity and public health implications. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;52:3297–302 https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01352-14.

Huang J, Zhang Z, Yang Y, Wang R, Zhao J, Jian F, et al. New genotypes of Enterocytozoon bieneusi isolated from Sika deer and Red Deer in China. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:879 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.00879.

Breton J, Bart-Delabesse E, Biligui S, Carbone A, Seiller X, Okome-Nkoumou M, et al. New highly divergent rRNA sequence among biodiverse genotypes of Enterocytozoon bieneusi strains isolated from humans in Gabon and Cameroon. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(8):2580–9 https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.02554-06.

Santín M, Fayer R. Microsporidiosis: Enterocytozoon bieneusi in domesticated and wild animals. Res Vet. 2011;90(3):363–71 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2010.07.014.

Deng L, Chai Y, Zhou Z, Liu H, Zhong Z, Hu Y, et al. Epidemiology of Blastocystis sp. infection in China: a systematic review. Parasite. 2019;26:41 https://doi.org/10.1051/parasite/2019042.

Stensvold CR, Alfellani M, Clark CG. Levels of genetic diversity vary dramatically between Blastocystis subtypes. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12(2):263–73 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2011.11.002.

Alfellani MA, Jacob AS, Perea NO, Krecek RC, Taner-Mulla D, Verweij JJ, et al. Diversity and distribution of Blastocystis sp. subtypes in non-human primates. Parasitology. 2013;140(08):966–71 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182013000255.

Zanzani SA, Gazzonis AL, Epis S, Manfredi MT. Study of the gastrointestinal parasitic fauna of captive non-human primates (Macaca fascicularis). Parasitol Res. 2016;115(1) https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-015-4748-9.

Wang J, Gong B, Yang F, Zhang W, Zheng Y, Liu A. Subtype distribution and genetic characterizations of Blastocystis in pigs, cattle, sheep and goats in northeastern China’s Heilongjiang Province. Infect Genet Evol. 2018;57:171–6 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2017.11.026.

Alfellani MA, Taner-Mulla D, Jacob AS, Imeede CA, Yoshikawa H, Stensvold CR, et al. Genetic diversity of Blastocystis in livestock and zoo animals. Protist. 2013;164:497–509 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.protis.2013.05.003.

Wang L, Cao L, Zheng S, Chang Y, Zhang K, Zhang S, et al. Molecular identification and biological characterization of Cryptosporidium muris from camels (Camelus bactrianus) in China. Parasit Vectors. 2021;14(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04862-8.

Cacciò SM, Beck R, Lalle M, Marinculic A, Pozio E. Multilocus genotyping of Giardia duodenalis reveals striking differences between assemblages a and B. Int J Parasitol. 2008;38:1523–31 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.04.008.

Xiao L, Singh A, Limor J, Graczyk TK, Gradus S, Lal A. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium Oocysts in samples of raw surface water and wastewater. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67(3):1097–101 https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.67.3.1097-1101.2001.

Sulaiman IM, Hira PR, Zhou L, Al-Ali FM, Al-Shelahi FA, Shweiki HM, et al. Unique endemicity of cryptosporidiosis in children in Kuwait. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:2805–9 https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.43.6.2805-2809.2005.

Buckholt MA, Lee JH, Tzipori S. Prevalence of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in swine: an 18-month survey at a slaughterhouse in Massachusetts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:2595–9 https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.68.5.2595-2599.2002.

Scicluna SM, Tawari B, Clark CG. DNA barcoding of Blastocystis. Protist. 2006;157:77–85 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.protis.2005.12.001.

Santín M, Fayer R. Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotype nomenclature based on the internal transcribed spacer sequence: a consensus. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2010;56(1):34–8 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.2008.00380.x.

Acknowledgments

We thank Let Pub (www.letpub.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U1904203) and the Leading talents of the Thousand Talents Program of Central China (19CZ0122). The sponsors played no role in study design, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, in writing the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LXZ conceived the study and participated in its design. KHZ, SJZ, YLW, and KW collected fecal samples and performed the experiments. YXW, AG, and KLH helped in interpretation of data. FCY and YCC performed the statistical analyses. KHZ and SJZ interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript. All of the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

In accordance with the Chinese Laboratory Animal Administration Act of 1988, the research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Henan Agricultural University (Approval No. IRB-HENAU-20180914-01). All of the fecal samples were collected from the animals with the consent of the zoo director, and none of the animals were injured during the specimen collection.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Specimens from wildlife at six zoos in Henan, China examined in this study.

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Nucleotide substitutions and indels at the ITS region of CHPM1 and CHDW1 genotypes.

Additional file 3: Table S3.

Primers and reaction conditions used in the characterization of the SSU rRNA gene of Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, Enterocytozoon bieneusi, Blastocystis sp. and gp60 gene.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, K., Zheng, S., Wang, Y. et al. Occurrence and molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, Enterocytozoon bieneusi, and Blastocystis sp. in captive wild animals in zoos in Henan, China. BMC Vet Res 17, 332 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-021-03035-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-021-03035-0