Abstract

Background

Avian cryptosporidiosis is a common parasitic disease that is caused by five species, which are well characterised at the molecular and biological level, and more than 18 genotypes for which we have limited information. In this study, we determined the occurrence and molecular characteristics of Cryptosporidium spp. in farmed ostriches in the Czech Republic.

Methods

The occurrence and genetic identity of Cryptosporidium spp. were analysed by microscopy and PCR/sequencing of the small subunit rRNA, actin, HSP70 and gp60 genes. Cryptosporidium avian genotype II was examined from naturally and experimentally infected hosts and measured using differential interference contrast. The localisation of the life-cycle stages was studied by electron microscopy and histologically. Infectivity of Cryptosporidium avian genotype II for cockatiels (Nymphicus hollandicus (Kerr)), chickens (Gallus gallus f. domestica (L.)), geese (Anser anser f. domestica (L.)), SCID and BALB/c mice (Mus musculus L.) was verified.

Results

A total of 204 individual faecal samples were examined for Cryptosporidium spp. using differential staining and PCR/sequencing. Phylogenetic analysis of small subunit rRNA, actin, HSP70 and gp60 gene sequences showed the presence of Cryptosporidium avian genotype II (n = 7) and C. ubiquitum Fayer, Santín & Macarisin, 2010 IXa (n = 5). Only ostriches infected with Cryptosporidium avian genotype II shed oocysts that were detectable by microscopy. Oocysts were purified from a pooled sample of four birds, characterised morphometrically and used in experimental infections to determine biological characteristics. Oocysts of Cryptosporidium avian genotype II measure on average 6.13 × 5.15 μm, and are indistinguishable by size from C. baileyi Current, Upton & Haynes, 1986 and C. avium Holubová, Sak, Horčičková, Hlásková, Květoňová, Menchaca, McEvoy & Kváč, 2016. Cryptosporidium avian genotype II was experimentally infectious for geese, chickens and cockatiels, with a prepatent period of four, seven and eight days post-infection, respectively. The infection intensity ranged from 1000 to 16,000 oocysts per gram. None of the naturally or experimentally infected birds developed clinical signs in the present study.

Conclusions

The molecular and biological characteristics of Cryptosporidium avian genotype II, described here, support the establishment of a new species, Cryptosporidium ornithophilus n. sp.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The genus Cryptosporidium Tyzzer, 1910 comprises protist parasites that infect epithelial cells in the microvillus border, primarily of the gastrointestinal tract, of all classes of vertebrates [1]. Until recently, only three bird-derived Cryptosporidium species, C. baileyi Current, Upton & Haynes, 1986, C. galli Pavlásek, 1999 and C. meleagridis Slavin, 1955, were described in birds [2,3,4]. Even with the recent descriptions of C. avium Holubová, Sak, Horčičková, Hlásková, Květoňová, Menchaca, McEvoy & Kváč, 2016 [5] and C. proventriculi Holubová, Zikmundová, Limpouchová, Sak, Konečný, Hlásková, Rajský, Kopacz, McEvoy & Kváč, 2019 [6], the number of described species in birds remains low relative to that in mammals. Eighteen Cryptosporidium genotypes (Cryptosporidium sp. YS-2017 genotype, avian genotype I, avian genotype IV, avian genotypes VI-IX, black duck genotype, Euro-Asian woodcock genotype, duck genotype, goose genotypes I-IV and goose genotype Id and finch genotypes I-III) have been identified [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15], primarily based on small subunit rRNA sequence data, across 17 avian orders worldwide [8, 9, 13, 16, 17]. Although avian Cryptosporidium spp. have been studied more frequently in recent years, research has been biased towards Cryptosporidium in poultry and pet birds, with comparatively little attention paid to Cryptosporidium in other bird groups [16, 18].

Unlike C. baileyi, which infects a broad range of birds from different orders, many recently described Cryptosporidium species and genotypes appear to have a relatively narrow host range. For example, Cryptosporidium avian genotype VI appears to be restricted to North American red-winged blackbirds [8], and Cryptosporidium goose and duck genotypes have been found only in anseriform birds [11, 15]. Similarly, C. avium and Cryptosporidium avian genotype I are almost exclusively found in psittacines and passerines, respectively [5,6,7, 19]. Cryptosporidium avian genotype II has been found predominantly in ostriches but also in other species within the order Struthioniformes as well as orders Galliformes and Psittaciformes (Table 1).

Cryptosporidium in ostriches was first reported in 1993 [20] and there have been several reports since then, although most have not described the molecular characteristics of isolates [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. Where molecular studies have been performed, with the exception of the rodent-specific C. muris Tyzzer, 1907, which was detected in 22 birds [32], C. baileyi [4, 32,33,34,35] and Cryptosporidium avian genotype II [19, 36] have been the only Cryptosporidium spp. reported in ostriches. While the biology of C. baileyi is well studied, there is limited information about Cryptosporidium avian genotype II.

In the present study, we report on the occurrence of Cryptosporidium spp. in farmed ostriches. For the most prevalent genotype in ostriches, Cryptosporidium avian genotype II, we further describe oocyst morphometry, experimental host specificity, developmental stage localization and molecular characteristics. Based on the collective data from this and previous studies, we conclude that Cryptosporidium avian genotype II is genetically and biologically distinct from the species of Cryptosporidium considered valid, and propose the name Cryptosporidium ornithophilus n. sp. for this genotype.

Methods

Specimens studied

Faecal samples were collected from ostriches on four farms in the Czech Republic. Faecal samples from juvenile (aged 9–12 months) and adult (older than three years) ostriches were individually collected into sterile plastic vials and stored at 4–8 °C until subsequent processing. Faecal smears were prepared from each sample, stained with aniline-carbol-methyl violet (ACMV), and examined for the presence of Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts [37]. Faecal samples were also screened for the presence of Cryptosporidium-specific DNA by PCR/sequencing (described below). Oocysts of C. ornithophilus n. sp. were purified from pooled faecal samples from a naturally infected juvenile common ostrich (no. 43588, Struthio camelus L.) kept on the farm number 4 using caesium chloride gradient centrifugation [38]. Purified oocysts were used for morphometry and preparation of the inoculum. The propidium iodide (PI) staining was used for test of oocysts viability [39]. Cryptosporidium ornithophilus n. sp. oocysts from a common ostrich were pooled and used to infect a single one-day-old chickens (chicken 0; Gallus gallus f. domestica). Oocysts recovered from the faeces of chicken 0 were used to infect other experimental animals. The purity of C. ornithophilus n. sp. isolate before performing the experimental infection and taking the measurements, and during the experiments was verified by the following procedure. The sequence of the original isolate (ostrich) was compared to the sequence obtained from chicken 0 and from tissue specimens and faecal samples of experimentally inoculated animals (below). The oocyst size of the original isolate was compared with isolates obtained from susceptible hosts.

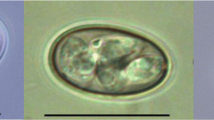

Oocyst morphometry

Oocysts of C. ornithophilus n. sp. from naturally and experimentally infected hosts (50 oocysts from each isolate) were examined and length and width measurements were taken using differential interference contrast (DIC) at 1000× magnification. All measurements are in micrometres and are given as the range followed by the mean ± standard deviation (SD) in parentheses. These measurements were used to calculate the length-to-width ratio. Sample containing purified C. parvum Tyzzer, 1912 oocysts from a naturally infected Holstein calf was used as a size control (n = 50). Size of oocysts was measured using the same microscope and by the same person. Each slide was screened a meandering path to prevent repeated measurement of an oocyst. Additionally, different staining methods were used for visualisation of oocysts. Faecal smears with C. ornithophilus n. sp. and C. parvum (data not shown) oocysts were stained by ACMV, modified Ziehl-Neelsen [ZN; 40], phenol staining [AP; 41] and labelled with genus-specific FITC-conjugated antibodies (IFA; Cryptosporidium IF Test, Crypto cel, Cellabs Pty Ltd., Brookvale, Australia). Morphometry was determined using digital analysis of images (Olympus cellSens Entry 2.1 software and Olympus Digital Colour camera DP73, Olympus Corporation, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan). Photomicrographs of C. ornithophilus n. sp. oocysts observed by DIC, ACMV, ZN, AP and IFA were stored at the Institute of Parasitology, Biology Centre of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Czech Republic.

Molecular analyses

Total genomic DNA was extracted from 20,000 purified oocysts, 200 mg of faeces, or 200 mg of tissue by bead disruption for 60 s at 5.5 m/s using 0.5 mm glass beads in a FastPrep®24 Instrument (MP Biomedicals, CA, USA) followed by isolation/purification using ExgeneTM Stool DNA mini (GeneAll Biotechnology Co. Ltd, Seoul, Korea) or DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified DNA was stored at − 20 °C. A nested PCR approach was used to amplify a partial region of the small subunit (SSU) rRNA [42, 43], actin [44], 70 kilodalton heat-shock protein (HSP70) [45] and gp60 [46,47,48] genes. The PCR conditions were slightly modified, for more details see [6]. Molecular grade water and DNA of C. parvum were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Secondary PCR products were detected in 1.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. PCR products were cut out from gel, purified using Gen Elute Gel Extraction Kit (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and sequenced in both directions with an ABI 3130 genetic analyser (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using the secondary PCR primers in commercial laboratory (SEQme, Dobříš, Czech Republic).

Phylogenetic analyses

The nucleotide sequences obtained in this study were edited using the ChromasPro 2.4.1 software (Technelysium, Pty, Ltd., South Brisbane, Australia) and aligned with reference sequences downloaded from GenBank using MAFFT version 7 online server (http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/software/). The most appropriate evolutionary models for phylogeny analyses and values of all parameters for each model were selected using the MEGAX software [49, 50]. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method based on the Tamura 3-parameter model [51] selected for SSU and HSP70 alignments and the general time reversible model [52] was selected for actin alignment. The trees with the highest log likelihood were shown. Bootstrap support for branching was based on 1000 replications. Phylogenetic trees obtained from the MEGAX (https://www.megasoftware.net/) were edited in CorelDrawX7 (https://www.coreldraw.com). Sequences of SSU (MN969954-MN969968), actin (MN973944-MN973958), HSP70 (MN973934-MN973943) and gp60 (MN973959-MN973963) generated in this study were deposited in the GenBank database.

Animals for transmission studies

Five adult cockatiels (Nymphicus hollandicus (Kerr)), five one-day-old chickens, five one-day-old geese (Anser anser f. domestica L.), five seven-day- and eight-week-old SCID mice (Mus musculus; strain C.B-17) and five seven-day and eight-week-old BALB/c mice were used for transmission studies. Three adult cockatiels, chickens, geese and seven-day and eight-week-old SCID and BALB/c mice used as a negative control. As a control, the infectivity of C. parvum from a naturally infected Holstein calf for three adult cockatiels, chickens, geese and seven-day and eight-week-old SCID and BALB/c mice was verified. All animals, except chickens, geese and seven-day-old mice, which were hatched under laboratory conditions, were screened every other day for the presence of oocysts of Cryptosporidium spp. and specific DNA two weeks prior to transmission studies. Cockatiels originated from breeders located in the Czech Republic and laboratory mice were obtained from Charles River (Germany).

Animal care

Rodents were individually housed in ventilated cages (Tecniplast, Buguggiate, Italy). Chickens and geese were housed in boxes and cockatiels were kept in separate aviaries. The size of boxes and aviaries were according to regulated by Czech legislation (Act No 246/1992 Coll., on protection of animals against cruelty). An external source of heat was used in the first five days for chickens and geese. Sterilized diet and water were available for all animals ad libitum. Animal caretakers wore sterile shoe covers and disposable coveralls and disposable gloves always they entered the experimental room. Wood-chip bedding and disposable protective clothing were removed from the experimental room and incinerated.

Experimental design

A total 20,000 purified oocysts of C. ornithophilus n. sp., suspended in 10 µl of distilled water, were dropped into the mouth/beak of each animal. Animals serving as negative controls were inoculated orally with 10 µl of distilled water. Faecal samples from all animals were screened daily for the presence of Cryptosporidium oocysts using ACMV staining and the presence of Cryptosporidium-specific DNA was confirmed using nested PCR/sequencing targeting the SSU gene. All experiments were terminated 30 days post-infection (dpi). Infection intensity was reported as the number of oocysts per gram (opg) of faeces, as previously described by Kváč et al. [53]. In addition, faecal consistency and colour and general health status were examined daily. The sequence identity of the Cryptosporidium DNA recovered from infected hosts to inoculum and original isolate at SSU, actin and HSP70 was verified in each experimentally infected animal.

Histopathological and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) examinations

Two animals from each group (at 10 and 20 dpi) were examined at necropsy. Tissue samples from oesophagus; stomach in rodents and proventriculus and ventriculus in birds; duodenum; jejunum (proximal, central and distal); ileum; caecum and colon were collected for histology and SEM followed by processing according [6]. Slides for histology were examined at 100–400× magnification and documented using Olympus cell Sens Entry 2.1 (Olympus Corporation, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a digital camera (Olympus DP73). Samples for SEM were examined using a JEOL JSM-7401F-FE SEM and documented using ETD Detector A PRED (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Additionally, DNA from tissue samples was isolated and the sequence identity to inoculum and original isolate at SSU, actin and HSP70 was verified.

Staining of mucosal smears

Wright staining procedures were used to visualize Cryptosporidium spp. developmental stages in the gastrointestinal tract of chickens [54]. Tissue samples of the large intestine (selected on the basis of histological examination) were washed with cold PBS with subsequent exposure to serum from Cryptosporidium-negative chickens for five min. The mucous membrane was gently scrapped with a scalpel and smeared on a glass slide. Wet mucosal smears were fixed with osmium vapour for 15 min followed by Wright staining for 6 min. Slides were viewed at 1000× magnification and documented using Olympus cell Sens Entry 2.1 (Olympus Corporation, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a digital camera (Olympus DP73).

Statistical analysis

Differences in Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts size were tested using Hotellingʼs multivariate version of the 2 sample t-test, package ICSNP: Tools for Multivariate Nonparametrics in R 4.0.0. [55]. The hypothesis tested was that two-dimensional mean vectors of measurement are the same in the two populations being compared.

Results

A total of 164 juvenile and 40 adult ostriches were screened for the presence of Cryptosporidium infection. Cryptosporidium spp. was detected on three out of four ostrich farms. Out of 204 faecal samples, five (2.5%) were microscopically positive for the presence of Cryptosporidium oocysts and 12 (5.9%) contained specific DNA of Cryptosporidium spp. (Table 2). All microscopically positive samples were also positive for Cryptosporidium DNA. Only juvenile ostriches (n = 12) were infected with Cryptosporidium spp. Screened animals had good health and faecal consistency appropriate to the age of birds and feeding.

All birds positive for Cryptosporidium-specific DNA were successfully genotyped by sequence analysis of SSU and actin genes (Table 2). ML trees constructed from SSU and actin sequences in this study showed the presence of C. ubiquitum Fayer, Santín & Macarisin, 2010 (n = 5) and C. ornithophilus n. sp. (n = 7; Table 2, Figs. 1, 2). HSP70 gene sequences were successfully amplified only from samples positive for C. ornithophilus n. sp. (Fig. 3). The C. ubiquitum gp60 gene was amplified and sequenced from five positive DNA samples from farm no. 1 (Table 2, Fig. 4). Sequences were identical to each other and clustered with subtype family XIIa (Fig. 4). Out of seven ostriches positive for C. ornithophilus n. sp., five shed microscopically detectable oocysts (6000–18,000 opg, Table 2). Birds positive for C. ubiquitum DNA did not shed oocysts detectable by microscopy.

Maximum likelihood tree (− ln = 3130.05) based on partial sequences of the gene encoding the small subunit rRNA (SSU), including sequences obtained in this study from naturally (red circle and bolded) and experimentally (green square and bolded) infected hosts. Tamura’s 3-parameter model was applied, using a discrete Gamma distribution and invariant sites. The robustness of the phylogeny was tested with 1000 bootstrap pseudoreplicates and numbers at the nodes represent the bootstrap values > 50%. The scale-bar indicates the number of substitutions per site. Sequences obtained in this study are identified by isolate number (e.g. 43201)

Maximum likelihood tree (− ln = 3641.49) based on partial sequences of the actin gene, including sequences obtained in this study from naturally (red circle and bolded) and experimentally (green square and bolded) infected hosts. The General Time Reversible model was applied, using a discrete Gamma distribution and invariant sites. The robustness of the phylogeny was tested with 1000 bootstrap pseudoreplicates and numbers at the nodes represent the bootstrap values > 50%. The scale-bar indicates the number of substitutions per site. Sequences obtained in this study are identified by isolate number (e.g. 43201)

Maximum likelihood tree (− ln = 2009.56) based on partial sequences of the 70 kDa heat-shock protein gene, including sequences obtained in this study from naturally (red circle and bolded) and experimentally (green square and bolded) infected hosts. Tamura’s 3-parameter model was applied, using a discrete Gamma distribution and invariant sites. The robustness of the phylogeny was tested with 1000 bootstrap pseudoreplicates and numbers at the nodes represent the bootstrap values > 50%. The scale-bar indicates the number of substitutions per site. Sequences obtained in this study are identified by isolate number (e.g. 43201)

Maximum likelihood tree (− ln = 4017.25) based on partial sequences of the 60 kDa glycoprotein gene of Cryptosporidium ubiquitum, Cryptosporidium apodemus genotype I and II and Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I, including sequences obtained in this study from naturally infected hosts (red circles and bolded). Tamura’s 3-parameter model was applied, using invariant sites. The robustness of the phylogeny was tested with 1000 bootstrap pseudoreplicates and numbers at the nodes represent the bootstrap values > 50%. The scale-bar indicates the number of substitutions per site. Sequences obtained in this study are identified by isolate number (e.g. 43201)

Cryptosporidium ornithophilus n. sp. oocysts did not infect 7-day-old and 8-week-old BALB/c or SCID mice, whereas 7-day-old BALB/c and both age categories of SCID mice were infected with C. parvum (control group, data not shown). All chickens, geese and cockatiels inoculated with oocysts of C. ornithophilus n. sp. developed infections. Oocysts or specific DNA were first detected at 4 dpi, 7 dpi and 8 dpi in geese, chickens and cockatiels, respectively (Fig. 5). The infection intensity ranged from 2000 to 16,000 opg in chickens and cockatiels and from 1000 to 8000 opg in geese (Fig. 5).

Course of infection of Cryptosporidium ornitophilus n. sp. in experimentally infected chickens (Gallus gallus f. domestica), geese (Anas platyrhynchos f. domestica) and cockatiels (Nymphicus hollandicus). a Infection intensity as number of oocysts per gram of faeces (opg). b Daily shedding of C. ornitophilus n. sp. based on coprological and molecular examination of faeces. Open squares indicate detection of specific DNA; filled squares indicate detection of oocysts by microscopy; grey rectangles indicate sacrifice and dissection of animal

Molecular, histological and SEM analyses and examination of stained mucosal smears of gastrointestinal tract tissue in birds with C. ornithophilus n. sp. showed the presence of developmental stages only in the caecum and colon of chickens and geese sacrificed 10 and 20 dpi (Figs. 6, 7). Few developmental stages were detected on each villus (Figs. 6, 7). Developmental stages were not detected in cockatiels, but specific DNA was detected exclusively in the caudal part of the ileum.

Histology sections of the caecum (a and b) and colon (c and d) of a chicken (Gallus gallus f. domestica) experimentally infected with 20,000 oocysts of Cryptosporidium ornitophilus n. sp., sacrificed 10 days post-infection. Attached developmental stages of C. ornitophilus n. sp. are indicated by arrows. Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) staining. Scale-bars: 50 µm

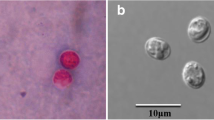

The morphometry of the developmental stages of C. ornithophilus n. sp. was examined in preparations with Wright’s stain (Table 3). Most of the detected developmental stages were enveloped by a parasitophorous sac, which appeared as an unstained halo (Fig. 8). A large number of oocysts was detected, and most were unstained with sporozoites not visible (Fig. 8). We were not able to differentiate between thin- and thick-walled oocysts. Free sporozoites were not detected, but a photomicrograph of sporozoites following oocyst excystation is included in Fig. 8. Mononuclear trophozoites were the most frequently observed developmental stage which also showed a high variability in size (Fig. 8; Table 3). Type I meronts, containing 8 merozoites, were observed frequently (Fig. 8), while Type II meronts, with 4 merozoites, were found rarely (Fig. 8). Free merozoites were found rarely (Fig. 8). Microgamonts were found rarely (Fig. 8), but macrogamonts, typified by a number of amylopectin granules in their cytoplasm and a foam-like appearance, were frequently observed (Fig. 8). Zygotes were lightly stained compared to the unstained oocysts (Fig. 8).

Developmental stages of Cryptosporidium ornitophilus n. sp. obtained from the colon of chickens (Gallus gallus f. domestica) experimentally infected with 20,000 oocysts and sacrificed 10 days post-infection. a Oocyst. b Sporozoite. c Mononuclear trophozoite. d Type I meront. e Type II meront. f Merozoites. g Microgamont. h Macrogamont. i Zygote. Scale-bar: 10 μm

SSU, actin and HSP70 sequences obtained from the original isolate of C. ornithophilus n. sp. (ostrich) were identical to isolates recovered from faeces of chicken 0 and all other birds infected during the whole experiment. Additionally, sequences obtained from the tissue specimens of caecum and colon of chickens and geese and in the ileum of cockatiels were also identical to the inoculum. The gene encoding gp60 was not successfully amplified in any animal experimentally infected with C. ornithophilus n. sp., indicating the absence of C. ubiquitum or other species and genotypes of Cryptosporidium spp. (e.g. C. parvum) that could be part of the inoculum.

The above data tend to justify the distinct status of Cryptosporidium ornitophilus n. sp., which is described below.

Family Cryptosporidiidae Léger, 1911

Genus Cryptosporidium Tyzzer, 1907

Cryptosporidium ornitophilus n. sp.

Syn. Cryptosporidium sp. ex Struthio camelus 2005 of Meireles et al. [59]; Cryptosporidium avian genotype II of Ng et al. [7], Nguyen et al. [36] and Sevá et al. [56]

Type-host: Struthio camelus Linnaeus (Struthioniformes: Struthionidae), common ostrich.

Other natural hosts: Alexandrine (Psittacula eupatria (L.)) (as Cryptosporidium avian genotype II [7]), chicken (Gallus gallus f. domestica) (as Cryptosporidium avian genotype II [57]), cockatiel (Nymphicus hollandicus) (as Cryptosporidium avian genotype II [7]), eclectus (Eclectus roratus (Müller)) (as Cryptosporidium avian genotype II [7]), galah (Eolophus roseicapilla (Vieillot)) (as Cryptosporidium avian genotype II [7]), Major Mitchell cockatoo (Cacatua leadbeateri (Vigors)) (as Cryptosporidium avian genotype II [7]), princess parrots (Polytelis alexandrae (Gould)) (as Cryptosporidium avian genotype II [7]), sun conure (Aratinga solstitialis (L.)) (as Cryptosporidium avian genotype II [7]), white-eyed parakeet (Aratinga leucophthalma (Statius Müller)) (as Cryptosporidium avian genotype II [56]).

Experimentally susceptible host: Gallus gallus f. domestica L. (Galliformes: Phasianidae), chicken; Anser anser f. domestica L. (Anseriformes: Anatidae), goose; Nymphicus hollandicus (Kerr) (Psittaciformes: Cacatuidae), cockatiel.

Type-locality: Ostrich farm at Židovice (50.4451578N, 14.2297606E), Czech Republic.

Other locality: Ostrich farm at Fulnek (49.7123761N, 17.9031931E) Czech Republic.

Type-material: Tissue samples in 10% formaldehyde and histological sections of infected cecum (no. 2/2019) and colon (no. 3/2019); genomic DNA isolated from faecal samples of naturally (isolation no. 43545) and experimentally (isolation no. 44331) infected chicken; genomic DNA isolated from cecum and colon of experimentally infected chicken (isolation no. 44331); hapantotypes: digital photomicrographs nos. DIC 1-13/43545, ACMV 1-11/43545, IF 1-9/43545, AP 1-12/43545, ZN IF 1-8/43545, PAS 2-3/2019 and SEM 744.75-744.79 and 745.68-745.74) and faecal smear slides with oocysts stained by ACMV staining from experimentally infected chicken (nos. 10/44331, 11/44331 and 12/44331). Specimens deposited at the Institute of Parasitology, Biology Centre of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Czech Republic.

Site of infection: Caecum, colon and bursa Farbricii (present study and [31]).

Distribution: As Cryptosporidium sp. ex Struthio camelus 2005: Brazil [36] and as Cryptosporidium avian genotype II: Australia [7], Brazil [56], China [57] and Vietnam [36].

Prepatent period: Gallus gallus f. domestica: 7 dpi; Nymphicus hollandicus: 8 dpi; Anser anser f. domestica: 4 dpi.

Patent period: At least 30 dpi in all experimentally infected birds (Gallus gallus f. domestica, Nymphicus hollandicus and Anser anser f. domestica)

Representative DNA sequences: Representative nucleotide sequences of the SSU (MN969957), HSP70 (MN973934) and actin (MN973947) genes were submitted to the GenBank database.

ZooBank registration: To comply with the regulations set out in Article 8.5 of the amended 2012 version of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) [58], details of the new species have been submitted to ZooBank. The Life Science Identifier (LSID) of the article is urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:593209C2-7F5B-47F9-93F3-02C81E8A747C. The LSID for the new name Cryptosporidium ornitophilus is urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:FE74CF3C-6734-424B-889E-C47108DEBA60.

Etymology: The species name is derived from the lack of host specificity among birds and its non-infectiousness to other vertebrates.

Description

Oocysts obtained from fresh feces specimens ex Struthio camelus ovoidal (Fig. 9), measuring 5.2–6.8 × 4.7–5.5 µm (6.1 ± 0.4 × 5.2 ± 0.2 µm) with a length/width ratio of 1.1–1.4 (1.19 ± 0.08). Oocyst wall single-layered, smooth, colorless. Micropyle and polar granule absent. Oocyst residuum present, composed of numerous small granules and one spherical globule. Four sporozoites measuring 5.5–6.6 × 0.5–0.6 µm (6.1 ± 0.3 × 0.6 ± 0.1 µm) present within each oocyst. For the measurements of other developmental stages see Table 3.

Oocysts of Cryptosporidium ornitophilus n. sp. visualized in various preparations. a Differential interference contrast microscopy. b Aniline-carbol-methyl violet staining. c Ziehl-Nielsen staining. d Auramine-phenol staining. e Labelled with anti-Cryptosporidium FITC-conjugated antibody. Scale-bars: 5 μm

Remarks

Oocysts in faecal smears showed typical Cryptosporidium ACMV, Ziehl-Neelsen, AP staining characteristics (Fig. 9). Fixed C. ornithophilus n. sp. oocysts were detectable with a FITC conjugated anti-Cryptosporidium oocyst wall antibody developed primarily for C. parvum (Fig. 9). There were no statistically significant size differences between oocysts from naturally infected ostriches and oocysts obtained from experimentally infected chickens (T2 = 2.249703, df1 = 2, df2 = 97, P = 0.1109), geese (T2 = 0.96185, df1 = 2, df2 = 97, P = 0.3858) and cockatiels (T2 = 2.221246, df1 = 2, df2 = 97, P = 0.1139; Table 4). Oocysts of C. ornithophilus n. sp. are larger than those of C. avium (T2 = 32.522, df1 = 2, df2 = 140, P < 0.0001) and C. parvum (T2 = 147.32, df1 = 2, df2 = 78, P < 0.0001) and smaller than C. proventriculi Holubová, Zikmundová, Limpouchová, Sak, Konečný, Hlásková, Rajský, Kopacz, McEvoy & Kváč, 2019 (T2 = 161,04 df1 = 2, df2 = 90, P < 0.0001) and C. galli (T2 = 35,522, df1 = 2, df2 = 78, P < 0.0001). Cryptosporidium ornithophilus n. sp. can be differentiated genetically from other Cryptosporidium spp. based on sequences of SSU, actin and HSP70 genes and on the basis of localization of life-cycle developmental stages in the host. While other bird-specific Cryptosporidium spp. primarily infect the proventriculus/ventriculus (C. proventiculi and C. galli) or small intestine (C. avium, C. meleagridis and C. baileyi) within gastrointestinal tract, C. ornithophilus n. sp. infects the caecum and colon.

Discussion

Birds are naturally parasitized with several Cryptosporidium species and genotypes [16, 18]. Here, we reported the occurrence of Cryptosporidium spp. in ostriches farmed commercially and described Cryptosporidium avian genotype II as a new species. Previous studies have shown that ostriches are frequently infected with C. baileyi [32,33,34] and C. ornithophilus n. sp. [19, 36, 59]; however, we detected C. ornithophilus n. sp. and C. ubiquitum. The absence of C. baileyi could be explained by the age of the birds screened in the present study. Previous studies reported C. baileyi in ostriches younger than 3 months with older birds being infected rarely or not at all [32, 34]. In this study, the occurrence of C. ornithophilus n. sp. in birds aged 9–14 months was 4.3% (7/164), which is similar to that reported in Vietnamese ostriches older than 12 months (5.8%; [36]). The absence of C. ornithophilus n. sp. in birds older than three years in this study could be due to age-related resistance or immunity, as described for C. baileyi, C. avium, C. parvum, C. muris and C. andersoni Lindsay, Upton, Owens, Morgan, Mead & Blagburn, 2000 in various hosts [60,61,62], but this needs to be examined experimentally.

Cryptosporidium ubiquitum is not typically found in birds so our finding of five ostriches on a single farm positive for this species was unexpected. Li et al. [63] also detected C. ubiquitum in birds (common hill mynas, Gracula religiosa L.) at commercial markets in China. It is possible that the detected DNA was due to mechanical passage, not an active infection. The cohabitation of livestock, companion and wild animals can result in Cryptosporidium oocyst passage through non-susceptible animals without establishing infection [64,65,66]. We cannot exclude that some wild animals may be the source of C. ubiquitum. Our failure to detect oocysts also suggests that any infection was likely to be of low intensity.

Five avian Cryptosporidium spp. (C. avium, C. baileyi, C. galli, C. meleagridis and C. proventriculi) have been recognized to date, and these differ in host range, oocyst morphometry, predilection sites and course of infection. The mean size of C. ornithophilus n. sp. oocysts from this study (6.1 × 5.1 µm) was similar to those reported as Cryptosporidium avian genotype II (6.0 × 4.8 µm) by Santos et al. [31] and Meireles et al. [59], and the oocysts are morphometrically indistinguishable from those of C. baileyi (6.3 × 4.6 μm) [2] and C. avium (6.3 × 4.9 μm) [5]. Oocysts of C. ornithophilus n. sp. are smaller than those of C. proventriculi (8.4 × 6.7 µm) [6] and C. galli (8.3 × 6.3 μm) [4] and larger than those of C. meleagridis (5.0 × 4.3 μm) [3]. Cryptosporidium ornithophilus n. sp. infects the caecum, colon and bursa Fabricii. Cryptosporidium baileyi also infects the caecum, colon and bursa Fabricii (in addition to other sites in the intestine and lungs) and C. avium also infects the caecum (in addition to the ileum) and their oocysts are similar in size to C. ornithophilus n. sp. [2, 5, 31], which would make it difficult to distinguish infections without the use of molecular tools. In addition to C. ornithophilus n. sp., C. baileyi and C. avium, C. meleagridis may also develop in the colon [67, 68], but these species could be distinguished based on oocyst size. In contrast to C. baileyi and C. avium, C. ornithophilus n. sp. did not develop at extraintestinal sites [5, 61, 69, 70].

Similar to Ng et al. [7] and Meireles et al. [59], we found no obvious clinical symptoms or mortality in birds naturally or experimentally infected with C. ornithophilus n. sp. There have been reports of clinical cryptosporidiosis, including prolapse of the phallus and cloaca, enteritis and pancreatitis, in ostrich chickens, but the isolates were not genotyped [21,22,23, 29,30,31] and other species, such as C. baileyi, may have been the cause of disease.

Although C. ornithophilus n. sp. has been reported most frequently in ostriches, reports of natural and experimental infections in alexandrine, chickens, cockatiels, eclectus, galah, geese, Major Mitchell cockatoo, princess parrots, sun conure and white-eyed parakeet suggests a broad host range [7, 19, 56, 71]. The prepatent period of C. ornithophilus n. sp. (4–8 dpi) is similar to C. meleagridis, C. baileyi and C. proventriculi [6, 72,73,74,75].

Phylogenetic analyses based on SSU, actin and HSP70 gene sequences showed that C. ornithophilus n. sp. is genetically distinct from known species and is most closely related to C. baileyi and C. avium. At the SSU locus, C. ornithophilus n. sp. shares 92.8% and 93.5% similarity with C. baileyi and C. avium, respectively. This is comparable to the similarity between C. andersoni and C. ryanae (91.1%) or C. muris and C. suis (93.3%). At the actin locus, similarities with C. baileyi and C. avium are 88.7% and 98.1%, respectively. In comparison, C. bovis and C. ryanae share 88.1% similarity and C. parvum and C. erinacei share 98.3% similarity at the actin locus. At the HSP70 locus, C. ornithophilus n. sp. shares 91.3% and 95.6% similarity with C. baileyi and C. avium, respectively. In comparison, C. parvum and C. erinacei share 99.2% similarity at the HSP70 locus.

Cryptosporidium ornithophilus n. sp. represents the 44th valid species within the genus Cryptosporidium (C. alticolis Horčičková, Čondlová, Holubová, Sak, Květoňová, Hlásková, Konečný, Sedláček, Clark, Giddings, McEvoy & Kváč, 2019, C. andersoni, C. apodemi Čondlová, Horčičková, Sak, Květoňová, Hlásková, Konečný, Stanko, McEvoy & Kváč, 2018, C. avium, C. bailey, C. bovis Fayer, Santín & Xiao, 2005, C. canis Fayer, Trout, Xiao, Morgan, Lai & Dubey, 2001, C. cichlidis Paperna & Vilenkin, 1996, C. cuniculus Robinson, Wright, Elwin, Hadfield, Katzer & Bartley 2010, C. ditrichi Čondlová, Horčičková, Sak, Květoňová, Hlásková, Konečný, Stanko, McEvoy & Kváč, 2018, C. ducismarci Traversa, 2010, C. erinacei Kváč, Hofmannová, Hlásková, Květoňová, Vítovec, McEvoy & Sak, 2014, C. fayeri Ryan, Power & Xiao, 2008, C. felis Iseki, 1979, C. fragile Jirků, Valigurová, Koudela, Křížek, Modrý & Šlapeta, 2008, C. galli, C. homai Zahedi, Durmic, Gofton, Kueh, Austen, Lawson, Callahan, Jardine & Ryan, 2017, C. hominis Morgan-Ryan, Fall, Ward, Hijjawi, Sulaiman, Fayer, Thompson, Olson, Lal & Xiao, 2002, C. huwi Ryan, Paparini, Tong, Yang, Gibson-Kueh, OʼHara, Lymbery & Xiao, 2015, C. macropodum Power & Ryan, 2008, C. meleagridis, C. microti Horčičková, Čondlová, Holubová, Sak, Květoňová, Hlásková, Konečný, Sedláček, Clark, Giddings, McEvoy & Kváč, 2019, C. molnari Alvarez-Pellitero & Sitjà-Bobadilla, 2002, C. muris Tyzzer, 1910, C. nasoris Hoover, Hoerr & Carlton, 1981, C. occultus Kváč, Vlnatá, Ježková, Horčičková, Konečný, Hlásková, McEvoy & Sak, 2018, C. parvum Tyzzer, 1912, C. proliferans Kváč, Havrdová, Hlásková, Daňková, Kanděra, Ježková, Vítovec, Sak, Ortega, Xiao, Modrý, Chelladurai, Prantlová & McEvoy, 2016, C. proventriculi, C. reichenbachklinkei Paperna & Vilenkin, 1996, C. rubeyi Li, Pereira, Larsen, Xiao, Phillips, Striby, McCowan & Atwill 2015, C. ryanae Fayer, Santin & Trout, 2008, C. scophthalmi Alvarez-Pellitero, Quiroga, Sitjà-Bobadilla, Redondo, Palenzuela, Pardós, Vázquez & Nieto, 2004, C. scrofarum Kváč, Kestřánová, Pinková, Květoňová, Kalinová, Wagnerová, Kotková, Vítovec, Ditrich, McEvoy, Stenger & Sak, 2013, C. serpentis Levine, 1980, C. suis Ryan, Monis, Enemark, Sulaiman, Samarasinghe, Read, Buddle, Robertson, Zhou, Thompson & Xiao, 2004, C. testudinis Ježková, Horčičková, Hlásková, Sak, Květoňová, Novák, Hofmannová, McEvoy & Kváč, 2016, C. tyzzeri Ren, Zhao, Zhang, Ning, Jian, Wang, Lv, Wang, Arrowood & Xiao, 2012, C. ubiquitum, C. varanii Pavlásek, Lávisková, Horák, Král & Král, 1995, C. viatorum Elwin, Hadfield, Robinson, Crouch & Chalmers, 2012, C. wrairi Vetterling, Jervis, Merrill & Sprinz, 1971 and C. xiaoi Fayer & Santín, 2009).

Conclusions

Morphological, genetic and biological data support the establishment of Cryptosporidium avian genotype II as a new species, Cryptosporidium ornithophilus n. sp.

Availability of data and materials

All type material and datasets on which the conclusions of the manuscript rely, are stored in the Institute of Parasitology, Biology Centre, Czech Academy of Sciences, České Budějovice, Czech Republic. Representative nucleotide sequences generated in this study were submitted to the GenBank database under the accession numbers MN969954-MN969968 and MN973934-MN973963.

Abbreviations

- ACMV:

-

aniline-carbol-methyl violet

- AP:

-

auramine phenol

- BSA:

-

bovine serum albumin

- DIC:

-

differential interference contrast

- DNA:

-

deoxyribonucleic acid

- dpi:

-

days post-infection

- FITC:

-

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- gp60:

-

60-kDa glycoprotein gene

- HSP70:

-

70-kDa heat-shock protein

- ICZN:

-

International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature

- IFA:

-

immunofluorescence assay

- ML:

-

maximum likelihood

- opg:

-

oocysts per gram

- PAS:

-

periodic acid-schiff

- PCR:

-

polymerase chain reaction

- SD:

-

standard deviation

- SCID:

-

Severe combined immunodeficiency

- SSU:

-

small subunit rRNA

- ZN:

-

Ziehl-Neelsen

References

Ryan U, Xiao L. Taxonomy and Molecular Taxonomy. In: Cacciò SM, Widmer G, editors. Cryptosporidium: parasite and disease. Wien: Springer; 2014. p. 3–42.

Current WL, Upton SJ, Haynes TB. The life cycle of Cryptosporidium baileyi n. sp. (Apicomplexa, Cryptosporidiidae) infecting chickens. J Protozool. 1986;33:289–96.

Slavin D. Cryptosporidium meleagridis (sp. nov.). J Comp Pathol. 1955;65:262–6.

Ryan UM, Xiao L, Read C, Sulaiman IM, Monis P, Lal AA, et al. A redescription of Cryptosporidium galli Pavlásek, 1999 (Apicomplexa : Cryptosporidiidae) from birds. J Parasitol. 2003;89:809–13.

Holubová N, Sak B, Horčičková M, Hlásková L, Květoňová D, Menchaca S, et al. Cryptosporidium avium n. sp. (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) in birds. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:2243–51.

Holubová N, Zikmundová V, Limpouchová Z, Sak B, Konečný R, Hlásková L, et al. Cryptosporidium proventriculi sp. n. (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) in Psittaciformes birds. Eur J Protistol. 2019;69:70–87.

Ng J, Pavlásek I, Ryan U. Identification of novel Cryptosporidium genotypes from avian hosts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:7548–53.

Chelladurai JJ, Clark ME, Kváč M, Holubová N, Khan E, Stenger BL, et al. Cryptosporidium galli and novel Cryptosporidium avian genotype VI in North American red-winged blackbirds (Agelaius phoeniceus). Parasitol Res. 2016;115:1901–6.

Helmy YA, Krucken J, Abdelwhab EM, von Samson-Himmelstjerna G, Hafez HM. Molecular diagnosis and characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. in turkeys and chickens in Germany reveals evidence for previously undetected parasite species. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0177150.

Ryan U, Xiao L, Read C, Zhou L, Lal AA, Pavlásek I. Identification of novel Cryptosporidium genotypes from the Czech Republic. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:4302–7.

Jellison KL, Distel DL, Hemond HF, Schauer DB. Phylogenetic analysis of the hypervariable region of the 18S rRNA gene of Cryptosporidium oocysts in feces of Canada geese (Branta canadensis): evidence for five novel genotypes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:452–8.

Morgan UM, Monis PT, Xiao L, Limor J, Sulaiman I, Raidal S, et al. Molecular and phylogenetic characterisation of Cryptosporidium from birds. Int J Parasitol. 2001;31:289–96.

Makino I, Inumaru M, Abe N, Sato Y. A new avian Cryptosporidium genotype in a 1-month-old caged brown wood owl (Strix leptogrammica) with severe dehydration and diarrhea. Parasitol Res. 2018;117:3003–8.

Cano L, de Lucio A, Bailo B, Cardona GA, Muadica ASO, Lobo L, et al. Identification and genotyping of Giardia spp. and Cryptosporidium spp. isolates in aquatic birds in the Salburua wetlands, Alava, northern Spain. Vet Parasitol. 2016;221:144–8.

Zhou L, Kassa H, Tischler ML, Xiao L. Host-adapted Cryptosporidium spp. in Canada geese (Branta canadensis). Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:4211–5.

Kváč M, McEvoy J, Stenger B, Clark M. Cryptosporidiosis in other vertebrates. In: Cacciò SM, Widmer G, editors. Cryptosporidium: parasite and disease. Wien: Springer; 2014. p. 237–326.

Nakamura AA, Meireles MV. Cryptosporidium infections in birds - a review. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2015;24:253–67.

Robertson LJ, Björkman C, Axén C, Fayer R. Cryptosporidiosis in farmed animals. In: Cacciò SM, Widmer G, editors. Cryptosporidium: parasite and disease. Wien: Springer; 2014. p. 149–236.

Nakamura AA, Simoes DC, Antunes RG, da Silva DC, Meireles MV. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. from fecal samples of birds kept in captivity in Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2009;166:47–51.

Gajadhar AA. Cryptosporidium species in imported ostriches and consideration of possible implications for birds in Canada. Can Vet J. 1993;34:115–6.

Bezuidenhout AJ, Penrith ML, Burger WP. Prolapse of the phallus and cloaca in the ostrich (Struthio camelus). J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1993;64:156–8.

Penrith ML, Burger WP. A Cryptosporidium sp. in an ostrich. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1993;64:60–1.

Jardine JE, Verwoerd DJ. Pancreatic cryptosporidiosis in ostriches. Avian Pathol. 1997;26:665–70.

Oliveira FC, Ederli NB, Ederli BB, Albuquerque MC, Dos Santos MD. Occurrence of Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts (Apicomplexa, Cryptosporidiidae) in ostriches, Struthio camelus L., 1758 (Aves, Struthionidae) reared in North and Lowered Coastline regions of the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2008;17(Suppl 1):322–5.

Sotiraki ST, Georgiades G, Antoniadou-Sotiriadou K, Himonas CA. Gastrointestinal parasites in ostriches (Struthio camelus). Vet Rec. 2001;148:84–6.

Symeonidou I, Diakou A, Papadopoulos E, Ponce-Gordo F. Endoparasitism of Greek ostriches: first report of Entamoeba struthionis and Balantioides coli. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Reports. 2019;18:100334.

Gajadhar AA. Host-specificity studies and oocyst description of a Cryptosporidium sp. isolated from ostriches. Parasitol Res. 1994;80:316–9.

Allwright DM, Wessels J. Cryptosporidium species in ostriches. Vet Rec. 1993;133:24.

Penrith ML, Bezuidenhout AJ, Burger WP, Putterill JF. Evidence for cryptosporidial infection as a cause of prolapse of the phallus and cloaca in ostrich chicks (Struthio camelus). Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 1994;61:283–9.

Ponce Gordo F, Herrera S, Castro AT, Garcia Duran B, Martinez Diaz RA. Parasites from farmed ostriches (Struthio camelus) and rheas (Rhea americana) in Europe. Vet Parasitol. 2002;107:137–60.

Santos MMAB, Periró JR, Meireles MV. Cryptosporidium infection in ostriches (Struthio camelus) in Brazil: clinical, morphological and molecular studies. Braz J Poultry Sci. 2005;7:113–7.

Qi M, Huang L, Wang R, Xiao L, Xu L, Li J, et al. Natural infection of Cryptosporidium muris in ostriches (Struthio camelus). Vet Parasitol. 2014;205:518–22.

Mammeri M, Adjou KT. Veterinary and public health importance of cryptosporidiosis in Algeria: an update and new insights. Rev Med Vet-Toulouse. 2019;170:164–73.

Wang R, Qi M, Jingjing Z, Sun D, Ning C, Zhao J, et al. Prevalence of Cryptosporidium baileyi in ostriches (Struthio camelus) in Zhengzhou, China. Vet Parasitol. 2011;175:151–4.

Elkarim Laatamna A, Holubová N, Sak B, Kváč M. Cryptosporidium meleagridis and C. baileyi (Apicomplexa) in domestic and wild birds in Algeria. Folia Parasitol (Praha). 2017;64:018.

Nguyen ST, Fukuda Y, Tada C, Huynh VV, Nguyen DT, Nakai Y. Prevalence and molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium in ostriches (Struthio camelus) on a farm in central Vietnam. Exp Parasitol. 2013;133:8–11.

Miláček P, Vítovec J. Differential staining of cryptosporidia by aniline-carbol-methyl violet and tartrazine in smears from feces and scrapings of intestinal mucosa. Folia Parasitol. 1985;32:50.

Arrowood MJ, Donaldson K. Improved purification methods for calf-derived Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts using discontinuous sucrose and cesium chloride gradients. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1996;43:89S.

Sauch JF, Flanigan D, Galvin ML, Berman D, Jakubowski W. Propidium iodide as an indicator of Giardia cyst viability. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:3243–7.

Henriksen SA, Pohlenz JF. Staining of cryptosporidia by a modified Ziehl-Neelsen technique. Acta Vet Scand. 1981;22:594–6.

Ley DH, Levy MG, Hunter L, Corbett W, Barnes HJ. Cryptosporidia-positive rates of avian necropsy accessions determined by examination of auramine O-stained fecal smears. Avian Dis. 1988;32:108–13.

Jiang J, Alderisio KA, Xiao L. Distribution of Cryptosporidium genotypes in storm event water samples from three watersheds in New York. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:4446–54.

Xiao L, Morgan UM, Limor J, Escalante A, Arrowood M, Shulaw W, et al. Genetic diversity within Cryptosporidium parvum and related Cryptosporidium species. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3386–91.

Sulaiman IM, Lal AA, Xiao LH. Molecular phylogeny and evolutionary relationships of Cryptosporidium parasites at the actin locus. J Parasitol. 2002;88:388–94.

Sulaiman IM, Morgan UM, Thompson RC, Lal AA, Xiao L. Phylogenetic relationships of Cryptosporidium parasites based on the 70-kilodalton heat shock protein (HSP70) gene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:2385–91.

Alves M, Xiao LH, Sulaiman I, Lal AA, Matos O, Antunes F. Subgenotype analysis of Cryptosporidium isolates from humans, cattle, and zoo ruminants in Portugal. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:2744–7.

Peng MM, Matos O, Gatei W, Das P, Stantic-Pavlinic M, Bern C, et al. A comparison of Cryptosporidium subgenotypes from several geographic regions. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2001;Suppl:28S–31S.

Li N, Xiao L, Alderisio K, Elwin K, Cebelinski E, Chalmers R, et al. Subtyping Cryptosporidium ubiquitum, a zoonotic pathogen emerging in humans. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:217–24.

Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–9.

Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;52:696–704.

Tamura K. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions when there are strong transition-transversion and G+C-content biases. Mol Biol Evol. 1992;9:678–87.

Tavaré S. Some probabilistic and statistical problems in the analysis of DNA sequences. In: Miura RM, editor. Some Mathematical questions in biology: DNA sequence analysis (lectures on mathematics in the life sciences). New York: American Mathematical Society; 1986. p. 57–86.

Kváč M, Ondráčková Z, Květoňová D, Sak B, Vítovec J. Infectivity and pathogenicity of Cryptosporidium andersoni to a novel host, southern multimammate mouse (Mastomys coucha). Vet Parasitol. 2007;143:229–33.

Tyzzer EE. An extracellular coccidium, Cryptosporidium muris (gen. et sp. nov.) of the gastric glands of the common mouse. J Med Res. 1910;23:487–509.

R Core Team. A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013. http://www.R-project.org/.

Sevá Ada P, Funada MR, Richtzenhain L, Guimarães MB, Souza SEO, Allegretti L, et al. Genotyping of Cryptosporidium spp. from free-living wild birds from Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2011;175:27–32.

Wang LM, Xue X, Li JQ, Zhou QJ, Yu YC, Du AF. Cryptosporidiosis in broiler chickens in Zhejiang Province, China: molecular characterization of oocysts detected in fecal samples. Parasite. 2014;21:36.

ICZN. International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature: amendment of articles 8, 9, 10, 21 and 78 of the international code of zoological nomenclature to expand and refine methods of publication. Bull Zool Nomencl. 2012;69:161–9.

Meireles MV, Soares RM, dos Santos MM, Gennari SM. Biological studies and molecular characterization of a Cryptosporidium isolate from ostriches (Struthio camelus). J Parasitol. 2006;92:623–6.

Holubová N, Sak B, Hlásková L, Květoňová D, Hanzal V, Rajský D, et al. Host specificity and age-dependent resistance to Cryptosporidium avium infection in chickens, ducks and pheasants. Exp Parasitol. 2018;191:62–5.

Lindsay DS, Blagburn BL. Cryptosporidiosis in birds. In: Dubey JP, Speer CA, Fayer R, editors. Cryptosporidiosis in man and animals. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1990. p. 133–48.

Kváč M, Sak B, Květoňová D, Secor WE. Infectivity of gastric and intestinal Cryptosporidium species in immunocompetent Mongolian gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus). Vet Parasitol. 2009;163:33–8.

Li Q, Li L, Tao W, Jiang Y, Wan Q, Lin Y, et al. Molecular investigation of Cryptosporidium in small caged pets in northeast China: host specificity and zoonotic implications. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:2905–11.

Kváč M, Hanzlíková D, Sak B, Květoňová D. Prevalence and age-related infection of Cryptosporidium suis, C. muris and Cryptosporidium pig genotype II in pigs on a farm complex in the Czech Republic. Vet Parasitol. 2009;160:319–22.

Sak B, Petrželková KJ, Květoňová D, Mynařová A, Shutt KA, Pomajbíková K, et al. Long-term monitoring of microsporidia, Cryptosporidium and Giardia infections in western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) at different stages of habituation in Dzanga Sangha Protected Areas, Central African Republic. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e71840.

Xiao L, Ryan UM, Graczyk TK, Limor J, Li L, Kombert M, et al. Genetic diversity of Cryptosporidium spp. in captive reptiles. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:891–9.

Pavlásek I. Localization of endogenous developmental stages of Cryptosporidium meleagridis Slavin, 1955 (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) in birds. Vet Med (Praha). 1994;39:733–42.

Akiyoshi DE, Dilo J, Pearson C, Chapman S, Tumwine J, Tzipori S. Characterization of Cryptosporidium meleagridis of human origin passaged through different host species. Infect Immun. 2003;71:1828–32.

Curtiss JB, Leone AM, Wellehan JF Jr, Emerson JA, Howerth EW, Farina LL. Renal and cloacal cryptosporidiosis (Cryptosporidium avian genotype V) in a major Mitchellʼs cockatoo (Lophochroa leadbeateri). J Zoo Wildl Med. 2015;46:934–7.

Lindsay DS, Blagburn BL, Sundermann CA, Hoerr FJ, Ernest JA. Experimental Cryptosporidium infections in chickens: oocyst structure and tissue specificity. Am J Vet Res. 1986;47:876–9.

Iijima Y, Itoh N, Phrompraphai T, Ito Y, Kimura Y, Kameshima S. Molecular prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. among companion birds kept in pet shops in Japan. Kor J Parasitol. 2018;56:281–5.

Hornok S, Bitay Z, Szell Z, Varga I. Assessment of maternal immunity to Cryptosporidium baileyi in chickens. Vet Parasitol. 1998;79:203–12.

Rhee JK, Seu YS, Park BK. Isolation and identification of Cryptosporidium from various animals in Korea. III. Identification of Cryptosporidium baileyi from Korean chicken. Korean J Parasitol. 1991;29:315–24.

Tůmová E, Skřivan M, Marounek M, Pavlásek I, Ledvinka Z. Performance and oocyst shedding in broiler chickens orally infected with Cryptosporidium baileyi and Cryptosporidium meleagridis. Avian Dis. 2002;46:203–7.

Lindsay DS, Blagburn BL, Sundermann CA, Giambrone JJ. Effect of broiler chicken age on susceptibility to experimentally induced Cryptosporidium baileyi infection. Am J Vet Res. 1988;49:1412–4.

Acknowledgements

We thank the farm owners and staff for their assistance in sample collection during this study.

Funding

This study was funded by the Czech Science Foundation (18-12364S), Grant Agency of University of South Bohemia (017/2018/Z and 028/2019/Z) and supported by MEYSCR (LM2015062Czech-BioImaging).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NH, MK and BS conceptualised the project. NH, AH and BS collected the samples. NH, MK and AH carried out the research. MK, NH and JM performed phylogenetic analysis. LT and RK performed histology, electron and light microscopy analysis. BS, LT and NH took care of experimental animals. MK, NH and JM wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All experimental procedures complied with the laws of the Czech Republic (Act No. 246/1992 Coll., on the protection of animals against cruelty). The study design was approved by the ethical committees at the Biology Centre of CAS, the State Veterinary Administration, and the Central Commission for Animal Welfare under protocols Nos 115/2013, 35/2018 and MZP/2019/630/1411.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Holubová, N., Tůmová, L., Sak, B. et al. Description of Cryptosporidium ornithophilus n. sp. (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) in farmed ostriches. Parasites Vectors 13, 340 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04191-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04191-2