Abstract

Background

There has been an increasing interest in researching on the effects of extremely low-frequency magnetic fields on living systems. The mechanism of action of extremely low-frequency magnetic fields on organisms has not been established. One of the hypotheses is related to induce changes in oxidative balance. In this study, we measured the effects of chronic unpredictable mild stress induced-oxidative balance of rat’s brain exposed to extremely low-frequency magnetic fields.

Methods

A first experiment was conducted to find out if 14 days of chronic unpredictable mild stress caused oxidative unbalance in male Wistar rat’s brain. Catalase activity, reduced glutathione concentration, and lipoperoxidation were measured in cerebrum and cerebellum. In the second experiment, we investigate the effects of 7 days extremely low-frequency magnetic fields exposure on animals stressed and unstressed.

Results

The main results obtained were a significant increase in the catalase activity and reduced glutathione concentration on the cerebrum of animals where the chronic unpredictable mild stress were suspended at day 14 and then exposed 7 days to extremely low-frequency magnetic fields. Interestingly, the same treatment decreases the lipoperoxidation in the cerebrum. The stressed animals that received concomitant extremely low frequency magnetic fields exposure showed an oxidative status like stressed animals by 21 days. Thus, no changes were observed on the chronic unpredictable mild stress induced-oxidative damage in the rat’s cerebrum by the extremely low-frequency magnetic field exposure together with chronic unpredictable mild stress.

Conclusions

The extremely low-frequency electromagnetic field exposure can partially restore the cerebrum antioxidant system of previously stressed animals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The universal distribution of electronic devices and their relationship with health care issues has raised increasing interest in investigating the effects of extremely low frequency magnetic fields (ELF-MF) on health. Recently, several epidemiological studies report a carcinogenic effect in residential and occupational exposition to ELF-MF [1, 2]. Therefore, a guideline for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatments against diseases caused by ELF-MF has been published [3]. In contrast, there are experimental and clinical studies that support the beneficial effects of ELF-MF exposure [3,4,5,6].

The mechanism of action of ELF-MF in biological systems has not been established. There are several hypotheses to explain it, which have been explored experimentally [7]. Various effects of ELF-MF have been observed, like inflammation, heat shock protein induction, DNA damage, changes in signal transduction involved in the genesis of cancer, and apoptosis induction [8]. There is one possible common cause that can elicit those effects: changes in oxidative balance [9]. Some investigations concerning this hypothesis have been carried out in vitro [10] and in vivo [11,12,13].

In rats, the effects induced by ELF-MF differ because there are variations in the intensity, frequency, and duration of the stimulus [12], and the age of the animals [14]. However, one variable that is important to consider in the effect of ELF-MF is the metabolic state of the animals, which has been poorly explored.

There is experimental evidence that different types of stress produce different effects on the oxidative balance system [15]. It is known that Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress (CUMS) generates an oxidative unbalance [16]. Our laboratory has found that acute restriction stress generates an increase in lipoperoxidation and oxidative damage to the brain. ELF-MF exposure together with restriction stress increases both parameters [17]. The present study investigates the effects of CUMS induced-oxidative balance of rat’s brain exposed to ELF-MF. Our research explores the interaction between CUMS and ELF-MF exposure to assess if mild stress influences the response to ELF-MF.

Materials and methods

All procedures were conducted in accordance with the official Mexican norms NOM-051-Z00-1995 and NOM-062-ZOO-1999. The experimental protocols were approved by institutional Local Committee of Research and Ethics of Faculty of Medicine and conducted under the authority of the Investigation Division, Faculty of Medicine, UNAM Project License (085/2016).

Animals

A total of 60 male Wistar rats aged 8 weeks (180–200 g) from the animal house facility of the Faculty of Medicine, UNAM, Mexico was used. To avoid other stressors in addition to those induced by the CUMS model, the rats, being gregarious animals, were housed in transparent boxes (2 rats/cage) that allowed them to see their congeners. Furthermore, the rats were always handled by only two people during all the processes. To reduce animal suffering, hygiene, safety, and environmental control measures were kept. The animal center maintained constant humidity of 60%, the temperature of 22 °C, and air ventilation, with a 12 h light-dark cycle, and with ad libitum access to rodent chow and water. The number of animals for each group (n) was decided based on previous studies and thus avoided the excessive number of rats [17]. The rats were adapted to the laboratory conditions for 4 days. Exclusion criteria if the animals presented a sickness or an infection of any type.

Experimental model chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS)

CUMS model consisted of applying a different kind of mild stressor each day for 21 days [18]. The stressors were: movement restriction for 2 h, 4 °C temperature exposure, the combination of both, forced swimming for 15 min, 45° cage tilting for 2 h, food deprivation for 24 h, water deprivation for 18 h, and isolation for 48 h. These were applied in a random form.

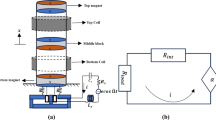

ELF-MF exposure

ELF-MF was applied with a device previously used in our laboratory [17]. Whole body of animals was exposed, placed in the center of two Helmholtz coils (internal diameter of 30 cm and separated by 30 cm). Coils were connected in parallel to a 120 V adjustable transformer (Staco Energy Products). Sinusoidal magnetic (60 Hz) flux density was 2.4 mT, which was measured using a hand-held Gauss/Tesla Meter (Alpha-Lab). The magnetic field background level was 50 µT. The temperature between the coils was monitored using a Hygro-thermometer (Extech Instruments), which remained constant during the 2 h of exposure (12:00–14:00 h).

Experiment I

An experiment was done to identify that the CUMS model was established before ELF-MF exposure, where the stress was applied for 14 days with its respective control. The CUMS was applied to 6 rats for 14 days to assess if they expressed oxidative stress (CUMS14) and the control group of 6 rats for 14 days (C14). Rats were euthanized at day 15 and cerebrum and cerebellum were analyzed for oxidative balance.

Experiment II

The experiment was carried out for 21 days. Six groups of 8 animals each were formed (Table 1).

Group 1. Control group for the whole 21 days period (C).

Group 2. Another control group was formed to find out if magnetic fields affect the oxidative balance of unstressed animals. For the first 14 days, the animals were in a control condition, and for the seven last days, they received ELF-MF exposure (C + MF).

Group 3. Stressed group (CUMS) for the whole 21 days period to compare with the other CUMS groups and with the control group.

Group 4. To find out if ELF-MF exposure together with the stress affects the oxidative balance, a CUMS + MF group was formed. CUMS was applied for 21 days and during the third week the rats also received ELF-MF exposure (CUMS + MF).

Group 5. To find out if the interruption of CUMS alters the effect of ELF-MF exposure on oxidative balance, another group was formed. Rats only received for 14 days CUMS, and then ELF-MF exposure during the next 7 days (preCUMS + MF).

Group 6. Finally, a physiological control group was formed with animals that received CUMS for 14 days, and the next 7 days they remained without any treatment (i.e., the rat cages were placed in between the coils, but the apparatus was shut off, preCUMS + Sham).

Rats were euthanized at day 22 and cerebrum and cerebellum were analyzed for oxidative balance.

Body weight control

The animals were weighed once a week to register the percentage of gain at the end of the experiment.

Plasma corticosterone levels

Plasma corticosterone concentration was quantified using an ELISA kit (Enzo Life Sciences), and a microplate reader Stat Fax 3200 (Awareness Technology Inc.) according to the manufacturer ́s instructions.

Euthanasia and tissue preparation

The average final weight was 300 g per rat. Before decapitation, the animals were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (200 mg/kg) [19]. The heads dissected, brains were removed and immediately separated into the cerebellum and cerebrum. Each area was stored and kept frozen at − 70 °C until the moment of their analyses.

Oxidative stress measurements

One investigator was aware of the stress treatments, but in the moment of the data analysis a second investigator did not know to what group the samples belonged. If a negative absorbance was recorded during the determination of enzyme activity, it was removed. But then we used an extra sample.

All chemicals were of analytical grade. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), GSH, 5,5ʹ-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic) acid (DTNB), and Na2HPO4 phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), trichloroacetic acid (TCA), tetraethoxypropane (TEP) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, Saint Louis, Missouri, USA.

Catalase enzyme activity

The determination of catalase (CAT) activity was based on the decrease in the absorbance of hydrogen peroxide as the reaction substrate. CAT activity in the supernatant of tissues was calculated according to the method reported by Aebi [20].

Ten microliter homogenates were added in 635 µL of phosphate buffer (Na2HPO4, 0.02 M) and 0.335 µL of H2O2 (0.03 M). The enzymatic reaction was measured at 240 nm in catalysis mode for 5 min of the reaction (spectrophotometer Genesys 10 S from Thermo Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Catalase activity was calculated as follow:

where, Δt, is the difference between times t2 and t1. Was reported kat/mg protein.

Reduced glutathione (GSH)

Twenty microliter homogenates were added in 0.610 mL Na2HPO4 phosphate buffer (0.3 M, pH 7.2) and DTNB (0.04% in 1% citrate). The solution was incubated for 5 min at room temperature. After centrifuging at 10,000 rpm for 5 min, the supernatant was collected and read at 412 nm. Results were extrapolated in a standard glutathione curve and reported in nmol/mg protein [21].

Lipoperoxidation

The final products concentration of lipoperoxidation were determined by thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARs), represented as malondialdehyde (MDA). MDA was determined in homogenate tissue with phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) at which the protein concentration was determined. An aliquot of 200 mL was taken which was precipitated with TCA (5% w/v) and was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 7 min. An aliquot of 100 µL of the supernatant was taken and 0.8% w/v TBA reagent solution (dissolved in 0.026 M Tris-HCl) and 0.6 N of HCl was added (final volume 1200 µL). After 20 min in a boiling bath a color developed. They were read by spectrometry at a wavelength of 535 nm. In addition, a standard curve was prepared with TEP (2.2–22 ng), which is equivalent to 0.72–7.2 ng MDA. The results were extrapolated to the curve and reported in ng/mg of protein previously determined [22].

Protein quantification

Protein was determined by the Lowry colorimetric method [23]. All the analyses were determined using a Spectrophotometer (JENWAY 6315).

Statistical analyses

The results from first experiment were analyzed by Student´s T-test and were expressed as mean ± SEM, with a p < 0.05. To compare the results of the second experiment, the Kruskal-Wallis test with multiple comparisons was used. They were expressed as mean ± SEM, with p < 0.05. Non-parametric prove of Correlation Spearman for association of variables (MDA vs. GSH and CAT vs. MDA) was used, with p < 0.05. All proves were evaluated using GraphPad Prism software v. 6.

Results

Experiment I. Effect of 14 days of CUMS on brain oxidative balance

Catalase activity, reduced glutathione, and malondialdehyde concentration were used as oxidative balance parameters. There were no significant differences in any of these oxidative balance parameters between CUMS14 and C14 groups analyzed on the cerebellum (Table 2).

The cerebrum of rats exposed to CUMS for 14 days showed a significant difference, with greater lipoperoxidation than of the control group (Table 3). No change in catalase activity or reduced glutathione levels in both groups was observed (p > 0.05).

Experiment II. Stress parameters

Animals submitted to stress exposition significantly increase the corticosterone concentration compared to control groups with p = 0.0187 (Fig. 1b). No significant differences were observed in the weight gain after the treatments (Fig. 1a).

Effect of 21 days CUMS and ELF-MF exposure on brain oxidative balance

The biomarkers of oxidative balance measured in the cerebellum are shown in Fig. 2. There was no statistical difference in these parameters in the cerebellum.

Figure 3 shows three biomarkers of oxidative stress measured in the cerebrum of rats. The catalase activity and GSH concentration significantly increase in the preCUMS + MF group compared to the other stressed groups (p < 0.05, Fig. 3a, b). There was significantly greater oxidation in CUMS, CUMS + MF, and preCUMS + Sham groups compared to the C group, expressed as higher levels of MDA (Fig. 3c). It is important to note that the preCUMS + MF group significantly reduced the MDA concentration compared to CUMS + MF group (Fig. 3c). In this same group -which showed less oxidation- significantly elevated both the catalase activity and the GSH level, compared to CUMS + MF group was observed.

Biomarkers of oxidative balance in the cerebrum. a Catalase (CAT kat/mg protein); b reduced glutathione (GSH nmol/mg protein); c malondialdehyde (MDA ng/mg protein). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 8). The data were analyzed by the Kruskal-Wallis test with multiple comparisons. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

The correlation of Spearman (r) was evaluated for MDA vs. GSH and MDA vs. CAT. A correlation coefficient r = 0.5787 with a p = 0.0038 and r = 0.3767 with p = 0.0152 respectively, were found.

Discussion

The data of the present study showed that two weeks of CUMS induced oxidative damage in the rat´s cerebrum. Magnetic field exposure was able to reduce the oxidation elicited by the stressful condition when the magnetic treatment was applied after removing the CUMS (preCUMS + MF). The change in oxidative balance was not observed when the rats were at the same time exposed to stress and MF (CUMS + MF).

Effect of 14 days of CUMS on brain oxidative balance (experiment I)

One of the best biomarkers of oxidative damage is the MDA. It has been considered a measure of lipoperoxidation by many authors [22, 24]. We showed the effect of 14 days CUMS exposure as an increase of MDA in cerebrum but not in the cerebellum. A previous report showed an increase of MDA in the hippocampus and cerebrum when rats were deprived of sleep for 24 h [25]. However, they did not find an increase in other oxidative biomarkers, as in the present study.

Experiment II. Stress parameters

Some authors considered that ELF-MF exposure acts as a mild stressor in organisms [9, 14]. We found elevated plasma corticosterone concentration in Wistar rats under stress conditions like in other reports [26]. No changes in plasma corticosterone were induced by MF exposure in any condition. Seven days of MF exposure did not induce elevation of corticosterone. The results are similar to previous reports, in which the plasma corticosterone concentration does not vary due to different types of MF exposures [27,28,29,30].

Chronic stress exposure induces a decrease in the weight of animals [31, 32]. However, in our study, the 21 days of CUMS exposure did not reduce the percentage of weight gain. Also, the ELF-MF exposure did not affect weight gain in any of the groups, regardless of whether they are non-stressed or stressed animals, similar to previous reports [14]. The MF exposure used in our study does not appear to induce stress in animals.

Effect of CUMS and ELF-MF exposure on brain oxidative balance

The effect of MF exposure on the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the brain is variable. Some reported ROS induction [12, 33,34,35,36], others found no changes [37, 38], or reduction [39].

Glutathione is an endogenous antioxidant and a cellular defense agent against oxidative damage. Physiological stress is related to a decreased level of GSH in brain tissue [40]. In the present report, the GSH concentration showed a decrease in stressed animals, which confirms that the CUMS model provokes deterioration in this antioxidant system. However, this decrease was only compared to the preCUMS + MS group. Besides, the exposure to ELF-MF does not alter the GSH level on unstressed animals. In the preCUMS + MF group the main effect was an increase in GSH concentration. The reports about the effect of MF on the glutathione system are variable. The long term MF exposure on the rat brains has shown a significant decrease in GSH [33]. In contrast, MF exposure (4 days) induced elevation of the GSH level in the guinea pig brains [41], similar to our result. Coskun, proposes that MF exposures affect various tissues distinctly because they have different tissue antioxidant status and responses.

Some authors propose that the mechanism of action of MF exposure is the formation of free radicals and the impairing of the antioxidant system [8]. This uncontrolled increase in ROS may result in lipid peroxidation [42]. The induction of oxidative damage by MF exposure in unstressed animals has been previously reported [43]. In our study, animals that were not stressed plus MF presented less lipoperoxidation than other groups. The difference between these results may be due to the time of MF since they chronically exposed their animals (24 h/day/7 days).

The CUMS induced an increase in cerebrum lipoperoxidation in all groups, except in the preCUMS + MF group. In this group, a significant reduction in MDA concentration was observed. Very few studies have reported the reduction of oxidative damage induced by MF exposure [44,45,46]. Recently, Wang and colleagues showed the effect of pulsed EMF treatment in a model of spinal cord injury on Wistar rats. The treatment reduces inflammation, oxidative damage, and promotes functional recovery in the model [46]. Ischemic stroke patients treated with extremely low-frequency MF improved activity and reduced plasma oxidative damage [44]. Seifirad et al., showed that single exposure (60 Hz and 0.5 mT) significantly increased lipid peroxidation on serum. They found an irreversible oxidative imbalance in chronic stimulation [47]. Therefore, these reports and our results allow us to propose that the antioxidant response of tissues to electromagnetic stimulation depends on the exposure parameters and the metabolic state of the organisms.

The CUMS + Sham group allows us to rule out the natural recovery after stopping stress and leaving the animals without any treatment. In the animals of this group, lipoperoxidation did not decrease. Besides, the increase in GSH concentration and catalase activity was not observed in the brain. Then, the increase in the antioxidant system and the lipoperoxidation reduction in the preCUMS + MF group is due to MF exposure.

Spearman correlation showed an inverse relation between MDA measurements and GSH. When there is depletion of GSH in the inside of the cell, there is lipoperoxidation, because there is much less of this antioxidant mechanism, and vice versa. There is also an inverse relation between MDA measurements and CAT activity. These results could be explained by the following proposed mechanism: ROS such as superoxide, hydroxyl ions, and peroxyl radicals cause injury in the brain when they are in excess, and the antioxidant defense is impaired. Continuous stress produces an excess of hydrogen peroxide. Thus, it can follow the route of the Fenton reaction producing an increase of hydroxyls, peroxides and therefore more lipoperoxidation. But in the preCUMS + MF animals, the magnetic exposure induces the increase of catalase activity that could lead to degrading the peroxide of hydrogen as much as possible (“protector shoot”), and therefore it avoids higher concentrations of MDA. The increase of CAT activity could stabilize and improve the reducing system increasing the concentration of glutathione. Another possible mechanism is the hormesis phenomenon, it has been proposed the redox status represents a form of it, characterized by beneficial biological effects at low levels of ROS production and harmful outcomes at high steady-state concentrations [48]. So, the magnetic field exposure applied after CUMS, could act as mild second stress, and allow the brain to lead to an antioxidant response, which could be beneficial. Both hypotheses should be explored in future experiments.

Conclusions

Seven days of magnetic field exposure reduces the cerebral oxidation elicited by the stressful condition, only if the magnetic treatment is applied after removing the CUMS. The extremely low-frequency electromagnetic field exposure can partially restore the cerebrum antioxidant system of previously stressed animals.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations to consider in upcoming experiments. Firstly, we used only adult male animals. Female rats were found to be more vulnerable to chronic mild stress [49]. Future experimental studies are needed to elucidate the role of gender on the response of the brain’s oxidative balance to EMF exposure. Secondly, our study did not fully explore the cellular mechanism to explain the protective effects observed. Different modulating mechanisms in addition to the oxidative balance presented in this work may also be involved, like changes in the immune system [50] or protection from apoptosis [51]. Thirdly, the magnetic flux density used in this work was 2.4 mT, like the use of magnetic therapy [3, 52]. Further work that includes other magnetic flux density is recommended.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to my work privacy institutional commitments but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- C:

-

Control

- C + MF:

-

Control + magnetic fields

- CAT:

-

Catalase

- CUMS:

-

Chronic unpredictable mild stress

- CUMS + MF:

-

Chronic unpredictable mild stress + magnetic fields

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- ELF-MF:

-

Extremely low-frequency magnetic fields

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immuno sorbent assay

- GSH:

-

Reduced glutathione

- MDA:

-

Malondialdehyde

- mT:

-

Milli Tesla

- preCUMS + MF:

-

Chronic unpredictable mild stress + magnetic fields

- preCUMS + Sham:

-

preChronic Unpredictable Mild Stress + Sham

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- SEM:

-

Standard error of mean

- TBARs:

-

Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances

References

Feychting M, Ahlbom A, Kheifets L. EMF and health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:165–9.

Gunnarsson LG, Bodin L. Occupational exposures and neurodegenerative diseases-a systematic literature review and meta-analyses. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:337.

Belyaev I, Dean A, Eger H, Hubmann G, Jandrisovits R, Kern M, Kundi M, Moshammer H, Lercher P, Muller K, Oberfeld G, Ohnsorge P, Pelzmann P, Scheingraber C, Thill R. EUROPAEM EMF guideline 2016 for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of EMF-related health problems and illnesses. Rev Environ Health. 2016;31:363–7.

Selvam R, Ganesan K, Narayana Raju KV, Gangadharan AC, Manohar BM, Puvanakrishnan R. Low frequency and low intensity pulsed electromagnetic field exerts its antiinflammatory effect through restoration of plasma membrane calcium ATPase activity. Life Sci. 2007;80:2403–10.

Hannemann PF, Mommers EH, Schots JP, Brink PR, Poeze M. The effects of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound and pulsed electromagnetic fields bone growth stimulation in acute fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134:1093–06.

Rosenberg O, Dinur Klein L, Gersner R, Kotler M, Zangen A, Dannon P. Long-term follow-up of MDD patients who respond to deep rTMS: a brief report. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2015;52:17–3.

Kovacic P, Somanathan R. Electromagnetic fields: mechanism, cell signaling, other bioprocesses, toxicity, radicals, antioxidants and beneficial effects. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2010;30:214–26.

Kivrak EG, Yurt KK, Kaplan AA, Alkan I, Altun G. Effects of electromagnetic fields exposure on the antioxidant defense system. J Microsc Ultrastruct. 2017;5:167–76.

Simko M. Cell type specific redox status is responsible for diverse electromagnetic field effects. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:1141–52.

Mattsson MO, Simko M. Grouping of experimental conditions as an approach to evaluate effects of extremely low-frequency magnetic fields on oxidative response in in vitro studies. Front Public Health. 2014;2:132.

Mattsson MO, Simko M. Is there a relation between extremely low frequency magnetic field exposure, inflammation and neurodegenerative diseases? A review of in vivo and in vitro experimental evidence. Toxicology. 2012;301:1–12.

Ciejka E, Kleniewska P, Skibska B, Goraca A. Effects of extremely low frequency magnetic field on oxidative balance in brain of rats. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011;62:657–61.

Manikonda PK, Rajendra P, Devendranath D, Gunasekaran B, Channakeshava, Aradhya SR, Sashidhar RB, Subramanyam C. Extremely low frequency magnetic fields induce oxidative stress in rat brain. Gen Physiol Biophys. 2014;33:81–90.

Falone S, Mirabilio A, Carbone MC, Zimmitti V, Di Loreto S, Mariggio MA, Mancinelli R, Di Ilio C, Amicarelli F. Chronic exposure to 50Hz magnetic fields causes a significant weakening of antioxidant defence systems in aged rat brain. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:2762–70.

Sahin E, Gumuslu S. Alterations in brain antioxidant status, protein oxidation and lipid peroxidation in response to different stress models. Behav Brain Res. 2004;155:241–8.

de Vasconcellos AP, Nieto FB, Crema LM, Diehl LA, de Almeida LM, Prediger ME, da Rocha ER, Dalmaz C. Chronic lithium treatment has antioxidant properties but does not prevent oxidative damage induced by chronic variate stress. Neurochem Res. 2006;31:1141–51.

Martinez-Samano J, Flores-Poblano A, Verdugo-Diaz L, Juarez-Oropeza MA, Torres-Duran PV. Extremely low frequency electromagnetic field exposure and restraint stress induce changes on the brain lipid profile of Wistar rats. BMC Neurosci. 2018;19:31.

Thompson AK, Fourman S, Packard AE, Egan AE, Ryan KK, Ulrich-Lai YM. Metabolic consequences of chronic intermittent mild stress exposure. Physiol Behav. 2015;150:24–30.

Zatroch KK, Knight CG, Reimer JN, Pang DS. Refinement of intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital for euthanasia in laboratory rats (Rattus norvegicus). BMC Vet Res. 2017;13:60.

Aebi H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:121–6.

Moron MS, Depierre JW, Mannervik B. Levels of glutathione, glutathione reductase and glutathione S-transferase activities in rat lung and liver. Biochim et Biophys Acta. 1979;582:67–78.

Torres-Duran PV, Paredes-Carbajal MC, Mascher D, Zamora-Gonzalez J, Diaz-Zagoya JC, Juarez-Oropeza MA. Protective effect of Arthrospira maxima on fatty acid composition in fatty liver. Arch Med Res. 2006;37:479–83.

Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–75.

Durnova NA, Afanaseva GA, Kurchatova MN, Zaraeva NV, Golikov AG, Bucharskaya AB, Golikov AG, Bucharskaya AB, Plastun VO, Andreeva NV. Content of oxidative stress markers in blood plasma under the action of extracts of Gratiola officinalis L., Helichrysum arenarium (L.) Moench, and anthocyanin forms of Zea mays L. Eksperimental’naia i klinicheskaia farmakologiia. 2015;78:36–40.

Melgarejo-Gutierrez M, Acosta-Pena E, Venebra-Munoz A, Escobar C, Santiago-Garcia J, Garcia-Garcia F. Sleep deprivation reduces neuroglobin immunoreactivity in the rat brain. Neuroreport. 2013;24:120–5.

Zhou JJ, Gao Y, Zhang X, Kosten TA, Li DP. Enhanced hypothalamic NMDA receptor activity contributes to hyperactivity of HPA axis in chronic stress in male rats. Endocrinology. 2018;159:1537–46.

Czeh B, Welt T, Fischer AK, Erhardt A, Schmitt W, Muller MB, Toschi N, Fuchs E, Keck ME. Chronic psychosocial stress and concomitant repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation: effects on stress hormone levels and adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:1057–65.

Kitaoka K, Kitamura M, Aoi S, Shimizu N, Yoshizaki K. Chronic exposure to an extremely low-frequency magnetic field induces depression-like behavior and corticosterone secretion without enhancement of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in mice. Bioelectromagnetics. 2013;34:43–51.

Mahdavi SM, Sahraei H, Yaghmaei P, Tavakoli H. Effects of electromagnetic radiation exposure on stress-related behaviors and stress hormones in male wistar rats. Biomol Ther (Seoul). 2014;22:570–6.

Szemerszky R, Zelena D, Barna I, Bardos G. Stress-related endocrinological and psychopathological effects of short- and long-term 50Hz electromagnetic field exposure in rats. Brain Res Bull. 2010;81:92–9.

Vieira JO, Duarte JO, Costa-Ferreira W, Morais-Silva G, Marin MT, Crestani CC. Sex differences in cardiovascular, neuroendocrine and behavioral changes evoked by chronic stressors in rats. Progr Neuro-psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;81:426–37.

Willner P. The chronic mild stress (CMS) model of depression: History, evaluation and usage. Neurobiol Stress. 2017;6:78–93.

Bediz CS, Baltaci AK, Mogulkoc R, Oztekin E. Zinc supplementation ameliorates electromagnetic field-induced lipid peroxidation in the rat brain. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2006;208:133–40.

Jelenkovic A, Janac B, Pesic V, Jovanovic DM, Vasiljevic I, Prolic Z. Effects of extremely low-frequency magnetic field in the brain of rats. Brain Res Bull. 2006;68:355–60.

Akdag MZ, Dasdag S, Ulukaya E, Uzunlar AK, Kurt MA, Taskin A. Effects of extremely low-frequency magnetic field on caspase activities and oxidative stress values in rat brain. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2010;138:238–49.

Cui Y, Ge Z, Rizak JD, Zhai C, Zhou Z, Gong S, Che Y. Deficits in water maze performance and oxidative stress in the hippocampus and striatum induced by extremely low frequency magnetic field exposure. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e32196.

Shehu A, Mohammed A, Magaji RA, Muhammad MS. Exposure to mobile phone electromagnetic field radiation, ringtone and vibration affects anxiety-like behaviour and oxidative stress biomarkers in albino wistar rats. Metab Brain Dis. 2016;31:355–62.

Di Loreto S, Falone S, Caracciolo V, Sebastiani P, D’Alessandro A, Mirabilio A, Zimmitti V, Amicarelli F. Fifty hertz extremely low-frequency magnetic field exposure elicits redox and trophic response in rat-cortical neurons. J Cell Physiol. 2009;219:334–43.

Medina-Fernandez FJ, Escribano BM, Aguera E, Aguilar-Luque M, Feijoo M, Luque E, Garcia-Maceira FI, Pascual-Leone A, Drucker-Colin R, Tunez I. Effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation on oxidative stress in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Free Rad Res. 2017;51:460–9.

Ahmad A, Rasheed N, Ashraf GM, Kumar R, Banu N, Khan F, Al-Sheeha M, Palit G. Brain region specific monoamine and oxidative changes during restraint stress. Can J Neurol Sci. 2012;39:311–8.

Coskun S, Balabanli B, Canseven A, Seyhan N. Effects of continuous and intermittent magnetic fields on oxidative parameters in vivo. Neurochem Res. 2009;34:238–43.

Halliwell B. Free radicals, antioxidants, and human disease: curiosity, cause, or consequence? Lancet. 1994;344:721–4.

Djordjevic NZ, Paunovic MG, Peulic AS. Anxiety-like behavioural effects of extremely low-frequency electromagnetic field in rats. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2017;24:21693–9.

Cichon N, Bijak M, Miller E, Saluk J. Extremely low frequency electromagnetic field (ELF-EMF) reduces oxidative stress and improves functional and psychological status in ischemic stroke patients. Bioelectromagnetics. 2017;38:386–96.

Osera C, Amadio M, Falone S, Fassina L, Magenes G, Amicarelli F, Ricevuti G, Govoni S, Pascale A. Pre-exposure of neuroblastoma cell line to pulsed electromagnetic field prevents H2 O2 -induced ROS production by increasing MnSOD activity. Bioelectromagnetics. 2015;36:219–32.

Wang C, Liu Y, Wang Y, Wei Z, Suo D, Ning G, Wu Q, Feng S, Wan C. Low frequency pulsed electromagnetic field promotes functional recovery, reduces inflammation and oxidative stress, and enhances HSP70 expression following spinal cord injury. Mol Med Rep. 2019;19:1687–93.

Seifirad S, Farzampour S, Nourbakhsh M, Amoli MM, Razzaghy-Azar M, Larijani B. Effects of extremely low frequency electromagnetic fields on paraoxonase serum activity and lipid peroxidation metabolites in rat. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2014;13:85.

Gloire G, Legrand-Poels S, Piette J. NF-kB activation by reactive oxygen species: fifteen years later. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:1493–505.

Dalla C, Antoniou K, Drossopoulou G, Xagoraris M, Kokras N, Sfikakis A, Papadopoulou-Daifoti Z. Chronic mild stress impact: are females more vulnerable? Neuroscience. 2005;135:703–14.

De Nicola M, Cordisco S, Cerella C, Albertini MC, D’Alessio M, Accorsi A, Bergamaschi A, Magrini A, Ghibelli L. Magnetic fields protect from apoptosis via redox alteration. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1090:59–68.

Johnson MT, Waite LR, Nindl G. Noninvasive treatment of inflammation using electromagnetic fields: current and emerging therapeutic potential. Biomed Sci Instrum. 2004;40:469–74.

Taradaj J, Ozon M, Dymarek R, Bolach B, Walewicz K, Rosinczuk J. Impact of selected magnetic fields on the therapeutic effect in patients with lumbar discopathy: a prospective, randomized, single-blinded, and placebo-controlled clinical trial. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2018;27:649–66.

Acknowledgements

Authors want to thank Lucía Beatriz Quesnel Galván for collaborating in reviewing the English language. Brianda Díaz Fragoso for collaborating in the enzyme quantification. Maria Antonia Rojas Terrazas for collaborating in animal management.

Guidelines and regulations

The study was carried out in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines. All methods were carried out in accordance with Official Mexican Standard, NOM-062-ZOO-1999 (Technical specifications for the production, care and use of laboratory animals), and Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals: Eighth Edition. National Research Council. 2011.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (IN214017) and (IN220120) to L V-D. Leticia R. Quesnel-Galván is a doctoral student from Programa de Doctorado en Ciencias Biomédicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) and received fellowship 290567 from CONACYT. They paid for the experimental materials. The funding bodies had no influence on the design of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LVD was leader of project, has designed of experiment, LRQG has determinate all the experiments, PVTD has performed the statistical analysis and editing of references. DEV has designed and built the ELF-MF device. All authors wrote, agree the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol was approved by institutional Local Committee of Research and Ethics of Faculty of Medicine and conducted under the authority of the Investigation Division, Faculty of Medicine, UNAM, Project License (085/2016).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Quesnel-Galván, L.R., Torres-Durán , P.V., Elías-Viñas, D. et al. Effect of extremely low frequency magnetic fields on oxidative balance in rat brains subjected to an experimental model of chronic unpredictable mild stress. BMC Neurosci 22, 52 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12868-021-00656-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12868-021-00656-x